In this paper we provide evidence that ECB's asset purchase programmes spill over into CESEE countries contributing to easing their financial conditions, both in the short- and in the long-term through different transmission channels. In the short run, a selected number of financial variables in CESEE markets appear to respond to the news related to ECB non-standard policies, moving in the expected direction. On a longer-term horizon, we found that that portfolio and banking capital inflows towards CESEE economies were affected by announcements of ECB's asset purchase programmes and actual asset purchases, pointing to the existence of a portfolio rebalancing and a (banking) liquidity channels in the latter case.

En este estudio se encuentra evidencia de que los programas de compra de activos del BCE repercuten en los países de la región de Europa Central, Oriental y Sudoriental (CESEE), de manera que contribuyen a facilitar su situación financiera tanto a corto como a largo plazo por medio de distintos canales de transmisión. A corto plazo, un número reducido de variables financieras en estos mercados CESEE parecen reaccionar a las noticias relacionadas con las políticas no convencionales del BCE y en la dirección esperada. En el horizonte a largo plazo hallamos que los flujos de portafolio y de capitales bancarios hacia las economías CESEE se vieron afectados por los anuncios de los programas de compra de activos y por las compras efectivas de activos del BCE, lo que señala la existencia de un canal de recomposición del portafolio y de un canal de liquidez (bancario) en el segundo caso.

Since the onset of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis the European Central Bank (ECB), similarly to other central banks in advanced economies (AEs), has implemented a series of non-standard monetary measures to address a range of unusual risks, including disturbances to liquidity in certain financial asset markets, to dispel the fears of a euro break-up and ‘redenomination risk’ and, more recently, to tackle the serious consequences of a prolonged period of excessively low inflation. Among these non-standard measures, asset purchase programmes have increasingly gained importance, accounting for around 30% of total assets in the Eurosystem's balance sheet as of late 2015.1

While most of the existing research on the international spillover effects of unconventional monetary policies (UMP) has focused on the US Fed's quantitative easing (QE) measures, the available evidence about the ECB's non-standard policies is relatively scant so far. The aim of this paper is to fill this gap, by gauging the impact of the ECB's asset purchase programmes on the financial markets of a set of Central, Eastern and South Eastern European (CESEE) economies,2 which are integrated with the euro area through strong financial linkages. Indeed, the euro area is the source of large capital flows to the CESEE economies and their domestic banking systems are largely dominated by euro area banking groups. Against this background, there is a strong case for assessing the possible spillover effects on CESEE financial markets stemming from the ECB's asset purchase programmes. Our expectation is that the ECB's security purchases have had significant effects on CESEE financial markets, supporting both cross-border portfolio flows and banking flows.

To start with, using an event study methodology, we look at how nominal exchange rates (FX), long-term sovereign yields, stock market indices and portfolio inflows to CESEE economies responded in the very short term to the announcements related to the ECB's asset purchase programmes. After controlling for global volatility developments and for macroeconomic surprises in major AEs, we find that the announcements triggered a broad-based appreciation of the nominal FX vis-à-vis the euro, an increase in domestic stock market indices and a moderate compression of long-term sovereign yields. These events also seem to be linked to larger portfolio capital flows, hinting at the existence, among other things, of a portfolio rebalancing transmission channel.

However, event study techniques can only provide a limited representation of the spillover effects from non-standard monetary measures, since they cannot capture longer-lasting financial effects or shed light on their subsequent transmission. It is therefore important to combine this approach with other methodologies, which take into account longer time spans and control for a wider set of macroeconomic and financial variables.

Therefore, to check for more persistent financial spillover effects from the euro area, we examine the impact of the ECB's asset purchase programmes on the dynamics of cross-border capital flows, looking separately at both portfolio investment (portfolio rebalancing channel) and international bank lending (banking liquidity channel). This is our main contribution to the existing literature: for each of these two transmission mechanisms, we compute fixed-effect panel regressions on quarterly data to try to infer the influence of a number of variables intended to proxy for the effect of the ECB's asset purchases programmes: a dummy variable for the announcement or impact effect of non-standard measures; a set of indicators for euro area liquidity and financial conditions to capture the likely effect of the actual implementation of such programmes of outright purchases of financial assets on secondary markets. In particular, the influence of this second set of indicators is evaluated both directly and indirectly, in the latter case by running the estimation procedure proposed by Ahmed and Zlate (2014) and Korniyenko and Loukoianova (2015) in order to isolate the changes in such indicators due to the ECB's asset purchase programmes. Our results show that such non-standard monetary measures may have fostered both cross-border portfolio investment flows into and foreign bank claims on the CESEE economies. To our knowledge, we are the first to provide evidence of the existence of this two important financial spillover channels into CESEE economies, in particular as banking flows are concerned.

The paper is structured as follows. After a brief overview of the main transmission channels of unconventional monetary policies and the related economic literature (Section 2), we provide a description of the different measures implemented by the ECB (Section 3). Section 4 presents the event study approach, while Section 5 illustrates our empirical strategy for detecting the longer-term financial spillover effects via the portfolio rebalancing channel (Section 5.2) and the banking liquidity channel (Section 5.3). Section 6 concludes the paper.

2Main transmission channels and related literatureSince 2008–2009, the slashing of the official reference rates to the zero lower bound (ZLB) and the implementation of unconventional measures by major central banks in AEs have spurred the interest of researchers in analysing the impact of these policies on global financial markets. The vast majority of the empirical studies rely upon short-term event study techniques, with only a handful of papers devoted to the analysis of longer-term and more persistent spillover effects.

Within the general functioning of outright asset purchase programmes (Bluwstein & Canova, 2015; Cova & Ferrero, 2015), the literature has focused on three main channels that transmit their effects to the financial system and the broader economy, both domestically and internationally: the portfolio rebalancing, the banking liquidity and the signalling channels.

The outright purchase of public and private securities, by modifying the size and the composition of the balance sheet of both the central bank and the private sector, may affect the economy through the portfolio rebalancing channel. As these measures involve the purchase of longer-duration assets, they increase the liquidity holdings of sellers, inducing a rebalancing of investors’ portfolios towards the preferred risk- return configuration. A necessary condition for this channel to be effective is an imperfect substitutability among different assets, i.e. assets are not perceived as perfect substitutes by investors, due to the presence of economic frictions (e.g., asymmetric information, limited commitment and limited participation; Cecioni, Ferrero, & Secchi, 2011; Falagiarda & Reitz, 2015). By purchasing a particular security, the central bank reduces the amount of that security held by private agents, usually in exchange for risk-free reserves. As a result, asset prices increase and long-term interest rates fall, creating more favourable conditions for economic recovery.

Outright asset purchases may also directly ease financial conditions and support bank lending to the private sector by improving the availability of funds through a banking liquidity channel. The counterpart of the purchase of long-term assets on private banks’ balance sheets is typically an increase in reserves. Since such reserves are more easily traded in secondary markets than long-term securities, there would be a decline in the liquidity premium which, in turn, would enable previously liquidity-constrained banks to extend credit to investors. This would result in a decline of borrowing costs and an increase in overall bank lending, including cross-border lending to emerging and developing countries (Lim, Mohapatra, & Stocker, 2014). The importance of this channel largely depends on the business cycle and on the conditions of the domestic banking sector.

The signalling channel operates when, through its unconventional measures, the central bank conveys information to the public about its intentions regarding the future evolution of short-term interest rates, the purchase of financial assets or the implementation of other measures to tackle market dysfunctions. If this communication is perceived by market participants as a signal of lower-than-previously-expected future policy rates, long-term yields may decline (via a lower risk-neutral component in interest rates). This channel is linked to a sort of confidence channel whereby the announcements, or actual operations, of the central bank may contribute to reducing economic uncertainty, reducing risk premia and bolstering activity. In this case, the credibility of the central bank is a crucial factor.

The above classification, of course, makes no claim to being exhaustive.3 In practice, there is a substantial degree of overlapping among the different channels, as shown by the literature. For this reason, it is often impossible to identify unambiguously which channels may have been at play.

The extant literature on the topic has mainly focused on the US experience, documenting the global dimension of the Fed's QE programmes extensively. Chen, Filardo, He, and Zhu (2012) are the first to have provided empirical evidence about the international spillovers of the US's large scale asset purchase (LSAP) programmes. By means of event-study techniques, they examine the short-term impact of the announcements of such policies on the financial markets of some emerging economies (EMEs)4: their results are consistent with the view that the Fed's QE measures led to significant cross-border spillovers (to EMEs) by raising equity prices, lowering government and corporate bond yields and compressing CDS spreads5; these effects, moreover, turned out to be greater than those prevailing in the US domestic markets. The existence and the extent of longer-term cross-country macro-financial linkages is then captured by means of a global vector error-correcting model, where unconventional monetary measures are modelled as a negative shock to the US term spread (Chen et al., 2012), to the ‘shadow’ federal fund rate (Chen, Filardo, He, & Zhu, 2014) or to the corporate spread (Chen, Filardo, He, & Zhu, 2015), respectively. Overall, they show a sizeable and widespread impact on EM financial markets via, among other things, stock prices, bank credit and FX pressures.6

Moore, Nam, Suh, and Tepper (2013) focus on both an international portfolio rebalancing channel and an asset pricing channel, by examining whether the Fed's LSAP programmes influenced capital flows from the US to EME local currency government bond markets, as well as the degree of the pass-through from long-term US to long-term EME local currency government bond yields. Based on a panel of 10 EMEs, for which data on foreign investment in government bonds are available, their estimates suggest that a 10bp reduction in long-term US Treasury yields triggers a 0.4pp increase in the foreign ownership share of government debt, with a reduction of government bond yields by approximately 1.7bp.

In a traditional empirical model of ‘push and pull’ determinants of capital flows to Asia and Latin America, Ahmed and Zlate (2014) isolate changes in US Treasury yields that can be attributed to the Fed's LSAP programmes and examine their effect on EME capital flows. Overall, their results point to the existence of a positive effect of the US UMP on total and portfolio inflows, which is greater for the gross (compared with net) component and for the portfolio (compared with total) category of flows. Nevertheless, the authors caution that unconventional US policies appear to be just one among several other important factors explaining changes in international capital flows to EMEs.

Similarly to Ahmed and Zlate (2014) and Lim et al. (2014) develop a procedure to test the importance of three distinct transmission channels (i.e. a liquidity, a portfolio rebalancing and a confidence channel) for the Fed's QE on gross financial flows (FDIs, portfolio flows and bank loans) in 60 developing countries.7 According to their analysis, observed capital inflows to EMEs are involved in all those three transmission channels; however, UMPs seem to have additional and largely unexplained effects different from those of the three channels8; lastly, different types of inflows may respond differently, with portfolio (especially bond) flows more sensitive to the identified transmission channels, and bank loans to the unexplained component of QE and FDIs.

All the papers surveyed above refer to the effects of the US UMP. Research on the international spillover effects of the ECB's non-standard monetary policy is relatively scant and again, generally based on short term event study techniques. Fratzscher, Lo Duca, and Straub (2014) attempt to quantify the impact of the earliest measures – the Supplementary and the Very Long-Term Refinancing Operations (S- and V-LTROs) of March 2008 and December 2011, respectively; the Securities Market Programme (SMP) of May 2010 and the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) of September 2012 – on a number of transmission channels affecting both quantities (international portfolio flows into bond and equity markets) and asset prices (equity, FX, long-term yields, risk premia for global banks and sovereigns), both in the euro area and globally. They find that the ECB's non-standard policies impacted positively on global equity markets and confidence, lowering credit risk among banks and sovereigns in both AEs and EMEs; however, the ECB's measures seem to lead to an international portfolio rebalancing of a much more limited size in the short term than the Fed's policies did.

Georgiadis and Gräb (2015) estimate the global impact of one of the latest ECB non-standard policies – i.e. the Expanded Asset Purchase Programme (EAPP), launched in January 2015 – on global equity prices, nominal exchange rates vis-à-vis the euro and bond yields. Their results show that the announcement of the launch of the EAPP brought about a global depreciation of the euro vis-à-vis its major trading partners, an increase in equity prices, but just a limited decline in global yields, probably reflecting already low levels. In testing for the existence of portfolio rebalancing, signalling and confidence channels, they find that the first two had some effects on eurozone equity prices, while eurozone sovereign bond yields seemed to have largely benefited from a confidence boost. This channel was also behind the rise in non-euro area equity prices, while the depreciation of the euro was mainly an effect of the signalling channel and, to a lesser extent, the portfolio rebalancing one. Finally, they find that domestic equities in different country aggregates except for the euro area only surged in response to the EAPP and OMT announcements, while the OMT and SMP ones led to a marked decline in intra-euro area sovereign bond yield spreads.

Falagiarda, McQuade, and Tirpák (2015) concentrate on the financial market effects in major non-euro area EU countries of Central and Eastern Europe (namely the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania). They find evidence of strong spillover effects from the ECB's non-standard policies on these financial markets, especially on bond yields and the FX; moreover, the impact of the SMP announcements appears to be more marked than those from the OMT and PSPP announcements. Both the portfolio rebalancing and the signalling channels were at work following the SMP announcements, while the OMT operated mainly via the confidence channel; lastly, both the confidence and the signalling channel were significant in transmitting the effects of the PSPP announcement.

3The ECB's asset purchase programmesSince the first half of 2009, the ECB has implemented a number of asset purchase programmes as part of its non-standard monetary policy toolkit. The Enhanced Credit Support (ECS), adopted in May 2009 to expand the existing set of available non-standard monetary measures introduced in earlier phases,9 contained the first programme of outright asset purchases, i.e. the Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP1), with the explicit goal of rekindling the functioning of the covered bond market, an essential source of refinancing for banks. This programme was further extended in November 2011 (CBPP2) and October 2014 (CBPP3).10

In May 2010, as tensions on the sovereign debt markets of some euro area countries emerged, the ECB introduced an additional asset purchase programme, the Securities Market Programme (SMP) involving the purchases of euro area government bonds to ensure adequate depth and liquidity in secondary markets. SMP purchases were made in two big waves, one in the first half of 2010 and the other in the second half of 2011, with their liquidity impact sterilized through specific operations. The purchases were conducted on a discretionary basis, according to daily market conditions.

The ‘whatever it takes’ speech by President Draghi in London in July 2012, at the height of the European sovereign debt crisis, paved the way for the adoption, in September 2012, of a further asset purchase programme, the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) initiative. Within this programme, the ECB could purchase an unlimited amount of sovereign bonds maturing in 1–3 years on request by a government asking for financial assistance, provided that the bond-issuing country implemented the specific measures (the conditionality principle) agreed under an adjustment programme to be signed with the ESFS (later the ESM). The declared objective of the OMT was to safeguard ‘(…) an appropriate monetary policy transmission and the singleness of the monetary policy (…)’ by lowering bond yields – whose high level was deemed to be unjustified if compared with the value implied by fundamentals (see for example, Di Cesare, Grande, Manna, & Taboga, 2012) – especially at the long end of the curve, thus reducing borrowing costs and providing confidence to investors in the sovereign bond markets. The OMT should therefore was introduced to overcome monetary and financial fragmentation in the euro area by removing the redenomination risk related to a breakup of the euro area. It is worth recalling that the OMT has never been implemented.

In June 2014, the ECB announced the credit easing package, to support lending to the real economy through the following strategies: (a) conducting a series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (T-LTROs) aimed at improving bank lending to the euro area's non-financial private sector, excluding loans to households for house purchase, over a window of two years and (b) intensifying preparatory work related to outright purchases of asset-backed securities (ABSPP), which started in October 2014 in parallel with the launch of the third wave of the CBPP.

In January 2015, the Governing Council announced the Expanded Asset Purchase Programme (EAPP), which adds a purchase programme for public sector securities (PSPP) to the existing private sector asset purchase programmes (CBPP3 and ABSPP), in order to address the risk of an overly long period of low inflation. Under the EAPP, the ECB has expanded its purchases to include bonds issued by euro area central governments, agencies and the European institutions, with combined monthly asset purchases to amount to €60 billion until September 2016 (subsequently moved to March 2017, with the ECB Governing Council's decision of December 2015) or until the adjustment in the path of inflation is consistent with the objective of monetary policy (an inflation rate below, but close to, 2% over the medium term). More recently, in April 2016 the Governing Council announced a further expansion of the EAPP: the upper limit on the monthly asset purchases was raised to €80 billion; moreover, investment grade euro-denominated bonds issued by non-bank corporations established in the euro area have been included in the list of eligible assets for regular purchases.

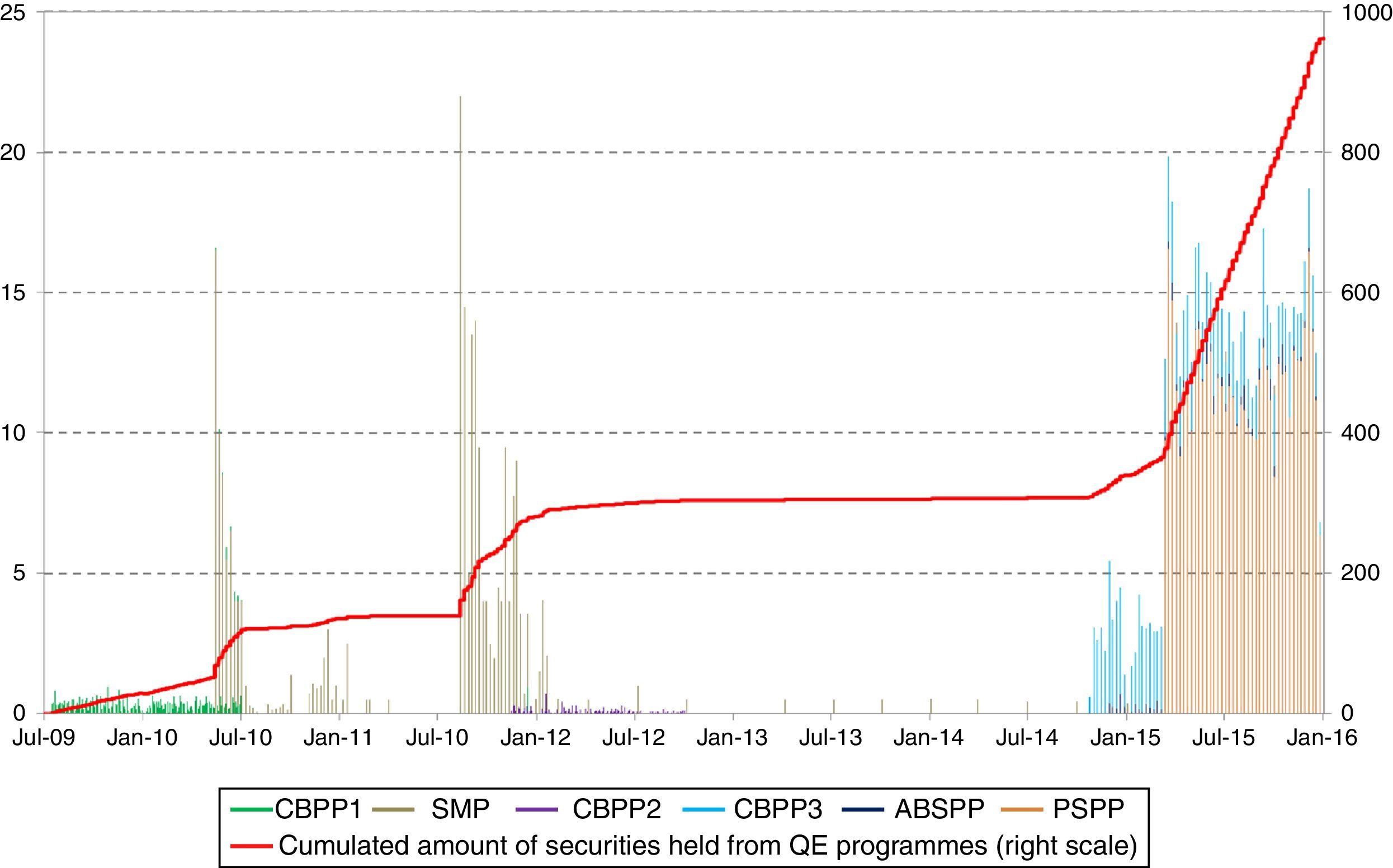

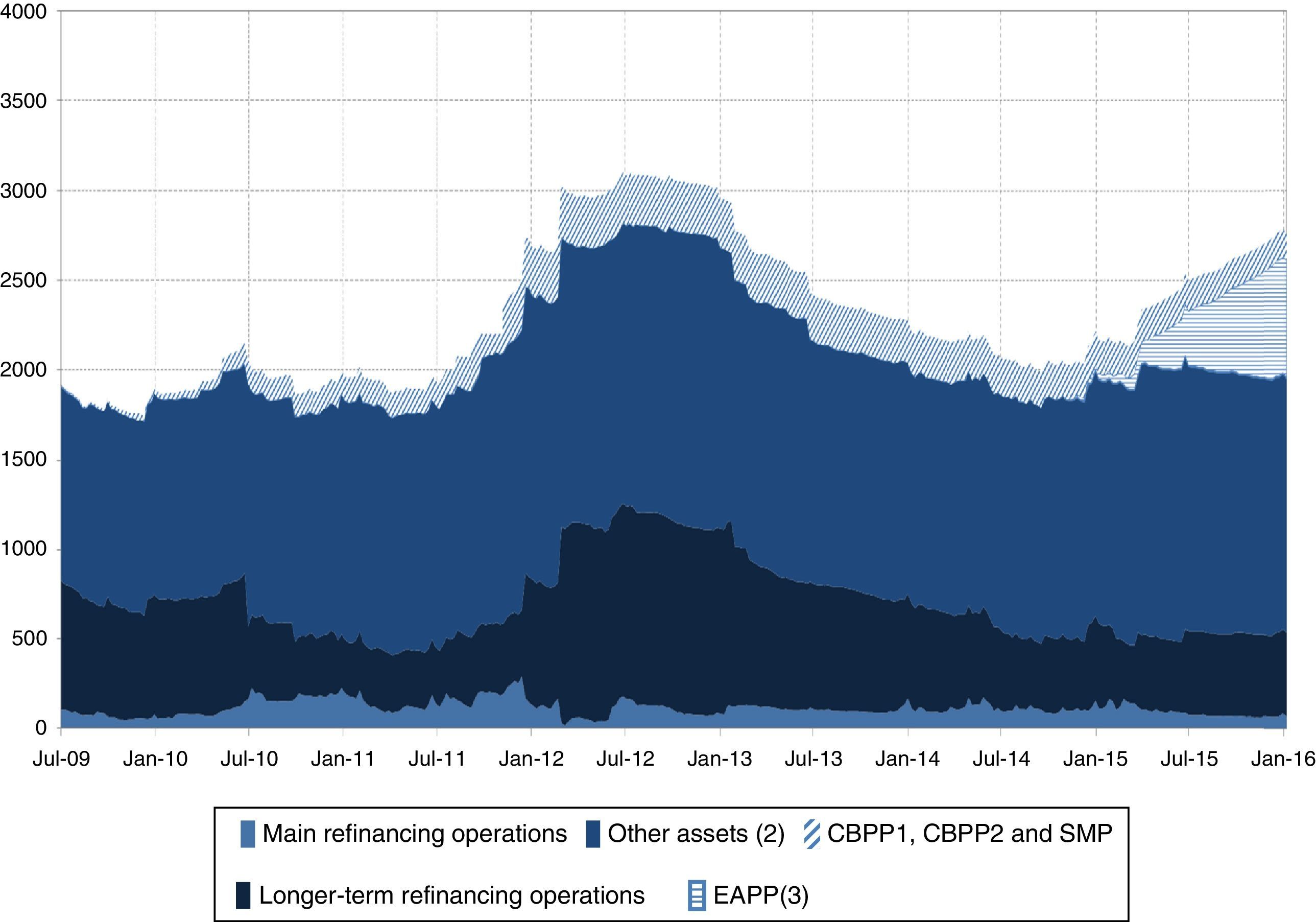

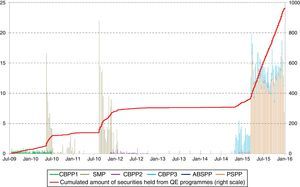

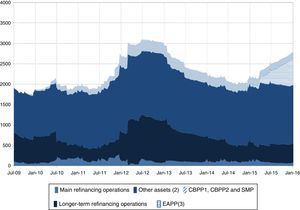

Fig. 1 shows the relative amounts purchased on a weekly basis by the ECB since autumn 2009, as well as the cumulated stock of financial assets held for monetary policy purposes. Fig. 2 shows the evolution of the different components of the asset side of the Eurosystem's balance sheet, namely the overall value of both the main and the longer-term refinancing operations, the securities purchased under the different programmes (i.e. the shaded areas representing, on the one hand, the CBPP1, CBPP2 and SMP and, on the other, the EAPP), as well as a further category of other assets. The overall share of securities purchased under all programmes as a share of the Eurosystem's total assets increased steadily to 10% between 2009Q3 and 2010Q3, hovered around this level until the end of 2014 and then started increasing again following the launch of the EAPP purchase programme to reach 30% as of end-2015.

ECB balance sheet (daily data, billions of euros). Note: (1) Shaded areas represent the ECB's asset purchase programmes. (2) Marginal lending facility, gold and other assets denominated in euros and foreign currency. (3) Covered Bond Purchase Programme 3 (CBPP3), Asset-Backed Purchase Programme (ABSPP) and Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP).

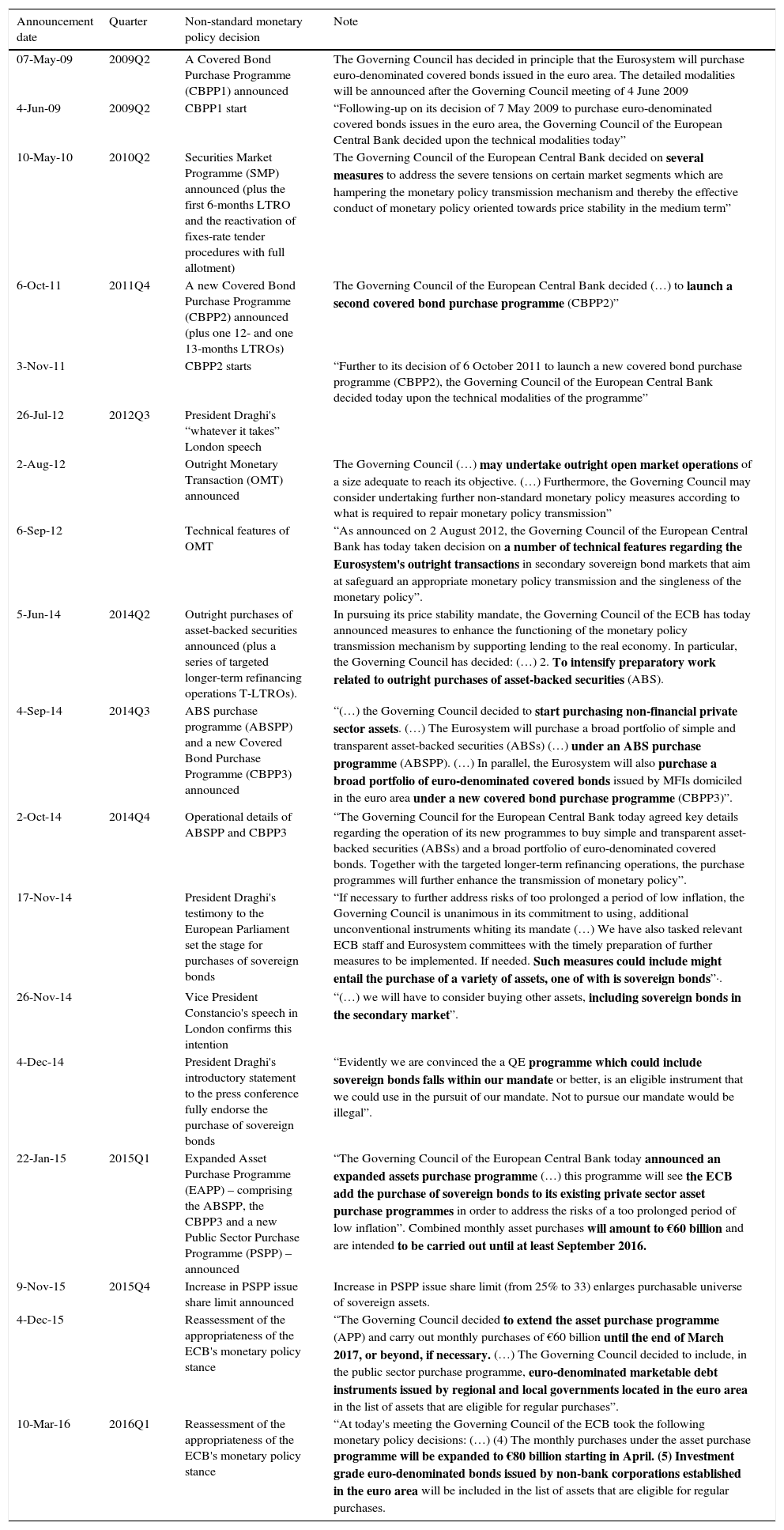

As a first step, we replicate the event study approach contained in much of the empirical literature on the topic. The basic idea is that, as long as financial markets are informationally efficient, the impact of both conventional and unconventional monetary policy measures should occur when they are disclosed, via changes in market expectations. This is the reason why we concentrate on the announcement or impact effect of the ECB's asset purchase programmes, where the first term refers to all sorts of communication (press conferences, press releases, speeches and so on). Table 1 contains a detailed chronology of all the identified events related to the announcement (and further modifications and extensions) of the ECB's non-standard measures implying the purchase of public and private financial assets on secondary markets: for each event, we report the day of the announcement, the type of measure as well as a brief description of the relative main individual features.

The ECB's asset purchase programmes.

| Announcement date | Quarter | Non-standard monetary policy decision | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 07-May-09 | 2009Q2 | A Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP1) announced | The Governing Council has decided in principle that the Eurosystem will purchase euro-denominated covered bonds issued in the euro area. The detailed modalities will be announced after the Governing Council meeting of 4 June 2009 |

| 4-Jun-09 | 2009Q2 | CBPP1 start | “Following-up on its decision of 7 May 2009 to purchase euro-denominated covered bonds issues in the euro area, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank decided upon the technical modalities today” |

| 10-May-10 | 2010Q2 | Securities Market Programme (SMP) announced (plus the first 6-months LTRO and the reactivation of fixes-rate tender procedures with full allotment) | The Governing Council of the European Central Bank decided on several measures to address the severe tensions on certain market segments which are hampering the monetary policy transmission mechanism and thereby the effective conduct of monetary policy oriented towards price stability in the medium term” |

| 6-Oct-11 | 2011Q4 | A new Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP2) announced (plus one 12- and one 13-months LTROs) | The Governing Council of the European Central Bank decided (…) to launch a second covered bond purchase programme (CBPP2)” |

| 3-Nov-11 | CBPP2 starts | “Further to its decision of 6 October 2011 to launch a new covered bond purchase programme (CBPP2), the Governing Council of the European Central Bank decided today upon the technical modalities of the programme” | |

| 26-Jul-12 | 2012Q3 | President Draghi's “whatever it takes” London speech | |

| 2-Aug-12 | Outright Monetary Transaction (OMT) announced | The Governing Council (…) may undertake outright open market operations of a size adequate to reach its objective. (…) Furthermore, the Governing Council may consider undertaking further non-standard monetary policy measures according to what is required to repair monetary policy transmission” | |

| 6-Sep-12 | Technical features of OMT | “As announced on 2 August 2012, the Governing Council of the European Central Bank has today taken decision on a number of technical features regarding the Eurosystem's outright transactions in secondary sovereign bond markets that aim at safeguard an appropriate monetary policy transmission and the singleness of the monetary policy”. | |

| 5-Jun-14 | 2014Q2 | Outright purchases of asset-backed securities announced (plus a series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations T-LTROs). | In pursuing its price stability mandate, the Governing Council of the ECB has today announced measures to enhance the functioning of the monetary policy transmission mechanism by supporting lending to the real economy. In particular, the Governing Council has decided: (…) 2. To intensify preparatory work related to outright purchases of asset-backed securities (ABS). |

| 4-Sep-14 | 2014Q3 | ABS purchase programme (ABSPP) and a new Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP3) announced | “(…) the Governing Council decided to start purchasing non-financial private sector assets. (…) The Eurosystem will purchase a broad portfolio of simple and transparent asset-backed securities (ABSs) (…) under an ABS purchase programme (ABSPP). (…) In parallel, the Eurosystem will also purchase a broad portfolio of euro-denominated covered bonds issued by MFIs domiciled in the euro area under a new covered bond purchase programme (CBPP3)”. |

| 2-Oct-14 | 2014Q4 | Operational details of ABSPP and CBPP3 | “The Governing Council for the European Central Bank today agreed key details regarding the operation of its new programmes to buy simple and transparent asset-backed securities (ABSs) and a broad portfolio of euro-denominated covered bonds. Together with the targeted longer-term refinancing operations, the purchase programmes will further enhance the transmission of monetary policy”. |

| 17-Nov-14 | President Draghi's testimony to the European Parliament set the stage for purchases of sovereign bonds | “If necessary to further address risks of too prolonged a period of low inflation, the Governing Council is unanimous in its commitment to using, additional unconventional instruments whiting its mandate (…) We have also tasked relevant ECB staff and Eurosystem committees with the timely preparation of further measures to be implemented. If needed. Such measures could include might entail the purchase of a variety of assets, one of with is sovereign bonds”·. | |

| 26-Nov-14 | Vice President Constancio's speech in London confirms this intention | “(…) we will have to consider buying other assets, including sovereign bonds in the secondary market”. | |

| 4-Dec-14 | President Draghi's introductory statement to the press conference fully endorse the purchase of sovereign bonds | “Evidently we are convinced the a QE programme which could include sovereign bonds falls within our mandate or better, is an eligible instrument that we could use in the pursuit of our mandate. Not to pursue our mandate would be illegal”. | |

| 22-Jan-15 | 2015Q1 | Expanded Asset Purchase Programme (EAPP) – comprising the ABSPP, the CBPP3 and a new Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) – announced | “The Governing Council of the European Central Bank today announced an expanded assets purchase programme (…) this programme will see the ECB add the purchase of sovereign bonds to its existing private sector asset purchase programmes in order to address the risks of a too prolonged period of low inflation”. Combined monthly asset purchases will amount to €60 billion and are intended to be carried out until at least September 2016. |

| 9-Nov-15 | 2015Q4 | Increase in PSPP issue share limit announced | Increase in PSPP issue share limit (from 25% to 33) enlarges purchasable universe of sovereign assets. |

| 4-Dec-15 | Reassessment of the appropriateness of the ECB's monetary policy stance | “The Governing Council decided to extend the asset purchase programme (APP) and carry out monthly purchases of €60 billion until the end of March 2017, or beyond, if necessary. (…) The Governing Council decided to include, in the public sector purchase programme, euro-denominated marketable debt instruments issued by regional and local governments located in the euro area in the list of assets that are eligible for regular purchases”. | |

| 10-Mar-16 | 2016Q1 | Reassessment of the appropriateness of the ECB's monetary policy stance | “At today's meeting the Governing Council of the ECB took the following monetary policy decisions: (…) (4) The monthly purchases under the asset purchase programme will be expanded to €80 billion starting in April. (5) Investment grade euro-denominated bonds issued by non-bank corporations established in the euro area will be included in the list of assets that are eligible for regular purchases. |

More specifically, we look at how nominal FX, long-term sovereign yields, stock market indices and portfolio inflows reacted over a one-day time window to the set of announcements related to the ECB's asset purchase programmes. Our econometric procedure implies the estimate of the following panel model with country fixed-effects:

where i is the country index and the αi's stand for the country fixed-effects.The dependent variable yi,t is, alternatively: (i) the one-day percentage change in a country's currency bilateral FX vis-à-vis the euro in percentage points; (ii) the one-day change in a country's 10-year government bond yield in basis points; (iii) the one-day return on a country's major stock market index in percentage points; (iv) the weekly amount of portfolio inflows into, respectively, a country's bond and equity sectors (in billions of dollars). The latter data come from the database provided by Emerging Portfolio Fund Research (EPFR).11

The explanatory variable of interest is APPEA,t, a dummy indicator equal to one when an important announcement related to asset purchase programmes is made and zero otherwise; in our case, the dummy indicator includes 17 positive occurrences from January 2009 to December 2015 (Table 1). The vector of control variables Ft includes: (i) contemporaneous surprises related to the release of macroeconomic indicators in the euro area and the US12; (ii) contemporaneous (log) changes in global volatility indicators, proxied by the VIX index in the case of stock market returns and capital inflows, the MOVE index in case of changes in long-term bond yields and the JPMorgan currency volatility index for FX changes. These volatility indicators are used to account for movements related to common shocks.13 The regressions are performed over the period January 2009 to December 2015.

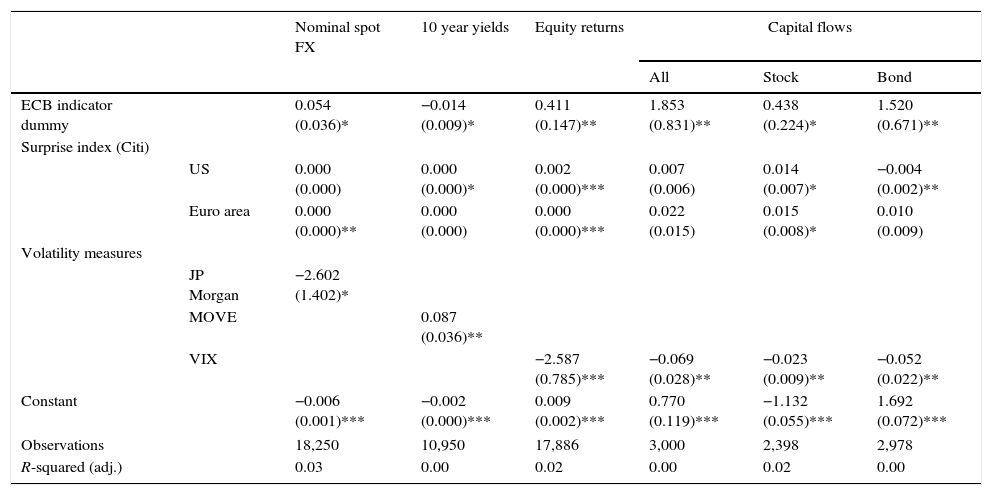

The estimated coefficient of APPEA,t turns out to be statistically significant and with the expected sign in all the specifications (Table 2). More precisely, the announcements caused a broad-based appreciation of CESEE currencies vis-à-vis the euro, an increase in the value of domestic stock market indices and a moderate compression of their respective long-term sovereign yields. These findings seem to support the hypothesis (Falagiarda et al., 2015) of a sort of international portfolio rebalancing, as shown by the positive impact on portfolio capital flows to CESEE economies in both the equity and debt compartments.14

Event study analysis.

| Nominal spot FX | 10 year yields | Equity returns | Capital flows | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Stock | Bond | |||||

| ECB indicator dummy | 0.054 (0.036)* | −0.014 (0.009)* | 0.411 (0.147)** | 1.853 (0.831)** | 0.438 (0.224)* | 1.520 (0.671)** | |

| Surprise index (Citi) | |||||||

| US | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000)* | 0.002 (0.000)*** | 0.007 (0.006) | 0.014 (0.007)* | −0.004 (0.002)** | |

| Euro area | 0.000 (0.000)** | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000)*** | 0.022 (0.015) | 0.015 (0.008)* | 0.010 (0.009) | |

| Volatility measures | |||||||

| JP Morgan | −2.602 (1.402)* | ||||||

| MOVE | 0.087 (0.036)** | ||||||

| VIX | −2.587 (0.785)*** | −0.069 (0.028)** | −0.023 (0.009)** | −0.052 (0.022)** | |||

| Constant | −0.006 (0.001)*** | −0.002 (0.000)*** | 0.009 (0.002)*** | 0.770 (0.119)*** | −1.132 (0.055)*** | 1.692 (0.072)*** | |

| Observations | 18,250 | 10,950 | 17,886 | 3,000 | 2,398 | 2,978 | |

| R-squared (adj.) | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | |

Note: The sample of 11 EMEs includes Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, FYR of Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania and Serbia. Robust standard errors are provided in parenthesis, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1. Nominal spot FX is the (one-day) percentage change in country I's currency bilateral exchange rate vis-à-vis the euro; 10 year yields is the (one-day) change in country I's 10-year government bond yield; Equity return is the (one-day) change in country i's major stock market index; Capital flows are weekly amount of portfolio inflows into country I’ bond and equity sectors the Surprise index (Citi) measures the contemporaneous surprises related to the release of macroeconomic indicators in the US and the Euro area; JPMorgan is a volatility index for EMEs FX changes; MOVE is a volatility index for long-term bond yields; VIX is the Chicago Board Option Volatility Index, a popular measure of the implied volatility of S&P 500 index options.

However, event study techniques can only provide a limited representation of the spillover effects from non-standard monetary measures, since they cannot capture longer-lasting financial effects or shed light on their subsequent transmission. It is therefore important to combine this approach with other methodologies, which take into account longer time spans and control for a wider set of macroeconomic and financial variables. This approach gives us the opportunity to analyze other important transmission channels, including the banking liquidity channel, which we suspect is more significant than the portfolio rebalancing one for CESEE economies in light of these countries’ deep banking interlinkages with the euro area. To our knowledge, we are the first to tackle this issue.

5Longer-term spillovers from the ECB's asset purchase programmesIn this section we examine whether, and to what extent, the implementation of the ECB's asset purchase programmes affected the (quarterly) flows of international portfolio investments and cross-border banking capital towards our sample of CESEE economies during the period from 2009Q3 to 2015Q4. This will allow us to detect the existence of both a portfolio rebalancing and a banking liquidity channel.

5.1The empirical strategyOur approach builds upon two strands of research. On the one hand, according to a large body of literature – which has grown around the seminal papers by Bruno and Shin (2012, 2013, 2014, 2015) and Rey (2013, 2015) – global liquidity and funding conditions, often described as the ‘ease of financing’ and largely dependent on the very accommodative conventional and unconventional monetary policies implemented by AEs’ central banks after the 2008–09 financial crisis, have contributed to a surge of cross-border international capital flows.15 On the other hand, Ahmed and Zlate (2014) and Korniyenko and Loukoianova (2015) show how to isolate, among the changes in global monetary and liquidity conditions, those directly attributable to the unfolding of the unconventional monetary measures implemented by AEs central banks. More specifically, this is done by substituting the available indicators of global liquidity conditions with some other instruments. We will apply this approach to the ECB's outright purchases of public and private financial assets on secondary markets carried out between 2009Q3 and 2015Q4 and see how they translated into a gradual easing of financial and liquidity conditions in the euro area; these, in turn, impacted on the cross-border portfolio and banking flows towards CESEE economies.

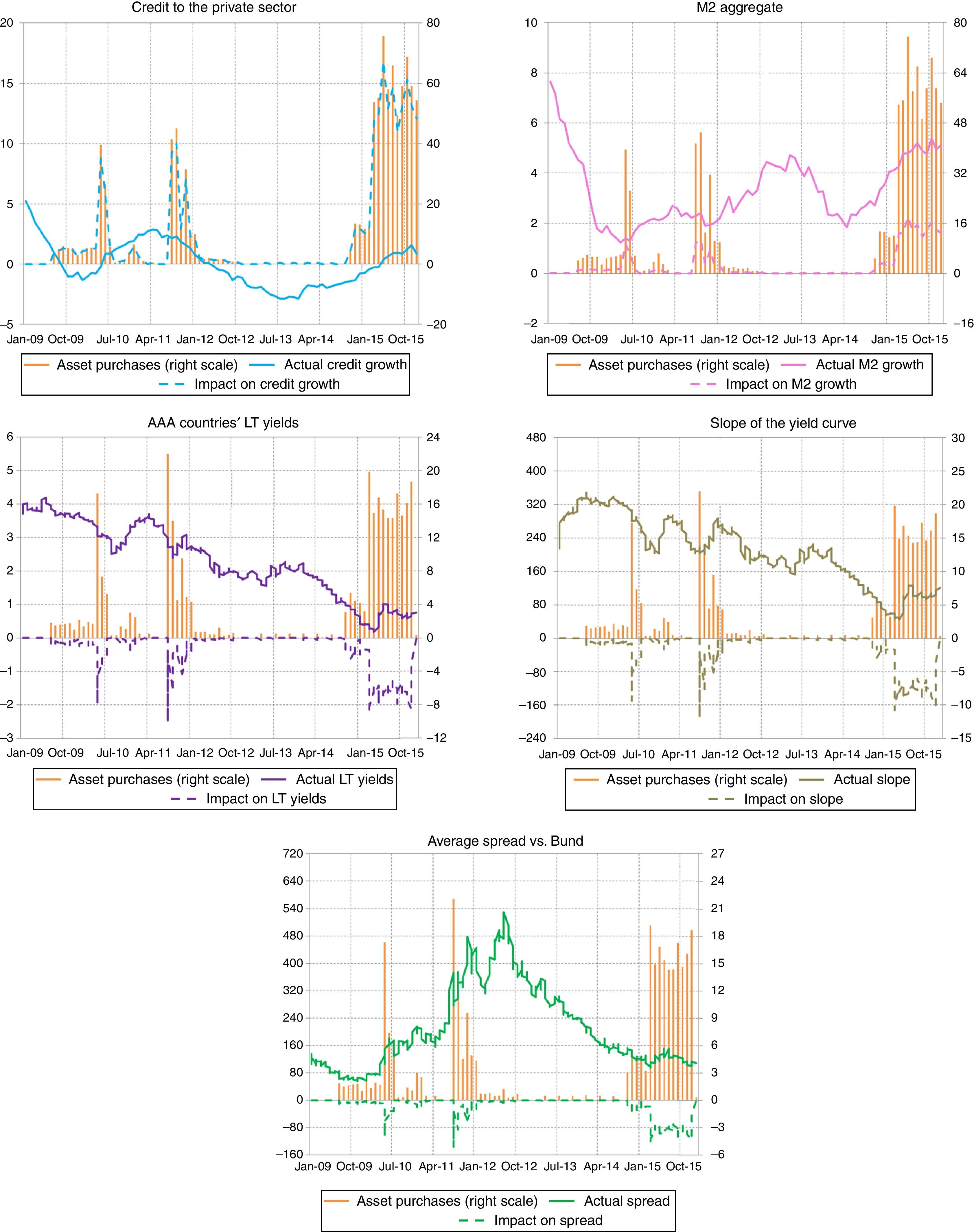

Our set of measures of financial and liquidity conditions in the euro area comprises a standard array of price and non-price indicators, extensively used in the empirical literature on global liquidity: the average level of 10-year yields on euro area AAA rated government bonds (Korniyenko & Loukoianova, 2015); the yield curve slope, defined as the differential between 10-year and 3-month yields of AAA euro area government bonds (Cerutti, Claessens, & Ratnovski, 2014); the yearly changes in the M2 aggregate (IMF, 2010) and in the credit to the private sector aggregate (Cerutti et al., 2014); the average spread between Italian and Spanish long-term yields and the German Bund (this variable should capture the redenomination risk related to the breakup of the euro area and the ensuing fragmentation of the euro area financial system).16 As documented by Albertazzi, Ropele, Sene, and Signoretti (2012), Neri (2013) and Zoli (2013), at the height of the euro area sovereign debt crisis, movements in the Italian and other euro area sovereign spreads were adversely transmitted to bank funding costs, lending conditions and the availability of credit for the real economy.

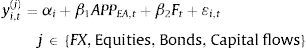

Our interest is focused on the changes of these components within the more accommodative liquidity and financial conditions in the euro area, which can be accounted for by the actual implementation of the ECB's asset purchase programmes. To isolate the effects of these non-standard measures on euro area liquidity conditions we follow the procedure proposed by Ahmed and Zlate (2014) and Korniyenko and Loukoianova (2015).

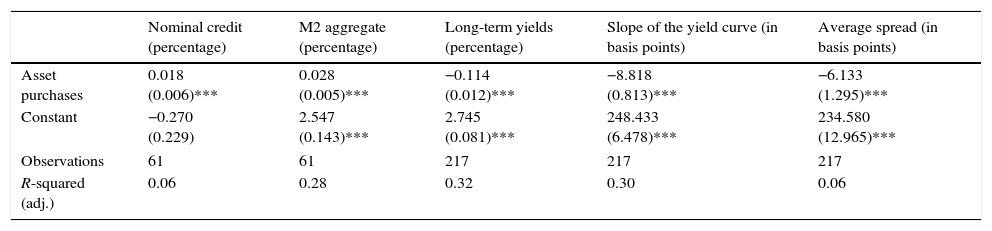

Initially, we run a simple OLS regression over the period from 2009Q3 to 2015Q4, where we use the one-quarter ahead ECB's actual gross asset purchases as an explicit determinant of euro area liquidity and financial condition indicators.17 As in Ahmed and Zlate (2014), the one-quarter ahead value of asset purchases, rather than the contemporaneous value, fits better, which perhaps is not surprising given that LSAPs are anticipated to some degree and announcements precede the actual purchases.18 The estimates show a significant relationship between the ECB's asset purchases, on the one hand, and the various indicators of financial and liquidity conditions in the euro area, on the other (Table 3). More precisely, the actual realization of these non-standard programmes has gone along with an acceleration in the growth of the M2 aggregate, the dynamics of credit to the private sector, a reduction in long-term government yields, a flattening of the yield curve and a compression in the sovereign spreads of peripheral euro area countries.

The ECB's asset purchases and euro area financial and liquidity conditions.

| Nominal credit (percentage) | M2 aggregate (percentage) | Long-term yields (percentage) | Slope of the yield curve (in basis points) | Average spread (in basis points) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asset purchases | 0.018 (0.006)*** | 0.028 (0.005)*** | −0.114 (0.012)*** | −8.818 (0.813)*** | −6.133 (1.295)*** |

| Constant | −0.270 (0.229) | 2.547 (0.143)*** | 2.745 (0.081)*** | 248.433 (6.478)*** | 234.580 (12.965)*** |

| Observations | 61 | 61 | 217 | 217 | 217 |

| R-squared (adj.) | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.06 |

Note: Robust standard errors are provided in parenthesis, ***p<0.01. Nominal credit is the yearly change in credit to the private sector; M2 aggregate is the yearly change in M2; Long-term yields is the average level of 10-year yield on euro area AAA rated government bonds; Slope of the yield curve is defined as the differential between 10-year and 3-month yields of euro area government bonds; Average spread is the average spread between Italian and Spanish 10-year yields and the corresponding German Bund.

Subsequently, we calculate the fitted values of the regressions in Table 3 (less the respective estimated constants) and use them as a proxy of the effect of the ECB's asset purchase programmes on euro area financial and liquidity conditions. Fig. 3 shows a graphical representation of both the actual liquidity indicators and the impact on them stemming from the ECB's non-standard measures.19

Actual and instrumented euro area liquidity indicators (quarterly data; % and billions of euros). Note: QE's impact on credit growth (QE's impact on M2 growth; QE's impact on LT yields; QE's impact on spread) represents the difference between the actual yearly growth rate of credit to the private sector (the actual yearly growth rate of the M2 aggregate; the quarterly average of AAA countries’ 10-year benchmark bonds; the quarterly average of spread between the Italian and Spanish long-term yields and the German Bund) and an estimate of what the growth rate (yield; spread) would have been without the asset purchase programmes which began in 2009Q3. The coloured charts are available in the electronic version of the article.

While the empirical literature has extensively investigated the ‘push and pull’ drivers of private capital flows to EMEs, the number of studies looking specifically at the impact of AE monetary policies is much more limited, in particular as regards those trying to isolate the impact of unconventional tools.20

In this section, we apply the procedure suggested by Ahmed and Zlate (2014) to check whether the ECB's asset purchase programmes might have influenced cross-border portfolio inflows to CESEE economies. Although the functional form is not derived from any structural model, we follow the basic tenets of the portfolio theory, according to which expected returns, risk and risk preferences matter for international investors’ asset allocations. In order to quantify the specific influence of the ECB's asset purchase programmes, we augment the basic empirical model with some extra explanatory variables, such as the actual measures of liquidity and financial conditions in the euro area, as well as that part of them explained by the working of the outright asset purchases; alternatively, we may use a simple dummy variable to investigate the behaviour of such flows during the quarters when the different rounds of asset purchase programmes were first announced or subsequently extended.

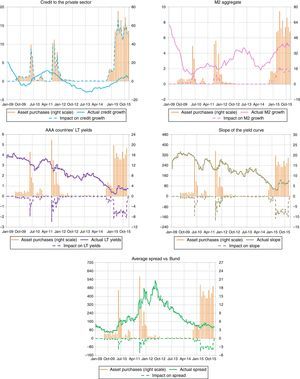

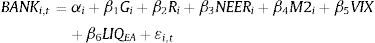

The empirical model is the following21:

where the international flows of portfolio investment to country i in period t, PORTi,t, are supposed to be related to: (i) growth in the two economies (Gi and GEA, real GDP growth in country i and in the euro area, respectively); (ii) the respective interest rates (Ri and REA, to capture the relative attractiveness of domestic versus foreign assets and thus capital flows); (iii) the VIX index, as a measure of global risk aversion.22 The term LIQEA comprises an array of non-price and price indicators of financial and liquidity conditions in the euro area – both the original series and those instrumented by the ECB's actual asset purchases – as well as the dummy indicator referred to above. As regards the expected sign of the relationship between the portfolio flows and the euro area financial and liquidity indicators, the extant literature points to a positive (negative) relationship with non-price (price) indicators (Cerutti et al., 2014) and to a positive relationship with the dummy indicator (Ahmed & Zlate, 2014). Finally, a time trend t is included in all our specifications.Our results are based on an unbalanced, quarterly panel dataset covering 11 CESEE economies over the period 2008Q1–2015Q4. To be consistent with the results obtained in the previous analysis, for the dependent variable we use data on portfolio investment flows by country of destination from the EU based mutual funds compiled by EPFR. Monthly data from the provider are added up throughout each quarter; the four-quarter sum of portfolio inflows is then divided by the four-quarter sum of domestic GDP (expressed in USD) at current prices to eliminate seasonality. For the explanatory variables, the preferred measure of short-term interest rates is represented by the quarterly average level of 3-month interbank rates.23 While the VIX is available at much higher frequencies, we follow the literature in using the log of its quarterly average value, thereby capturing more persistent changes in market volatility. To guard against biases from simultaneity or reverse causality, lagged values of all the regressors are used in the estimation except the VIX, which is assumed to be exogenous.

Column (1) in Table 4 shows the results of the model without liquidity indicators: overall, the estimated coefficients of the standard explanatory variables have the expected signs and are statistically significant.24 We then add to this basic representation, one by one, all the variables measuring the financial and liquidity conditions in the euro area, as well as their instrumented counterparts and the dummy indicator. We have chosen not to include all the latter indicators simultaneously, given the constraint represented by the relatively small size of the sample and the resulting limited degrees of freedom available for estimation purposes. Columns (2)–(5) of Table 4 contain the results for the original series, Columns (6) those for the dummy indicator and Columns (7)–(9) those for the instrumented indicators.

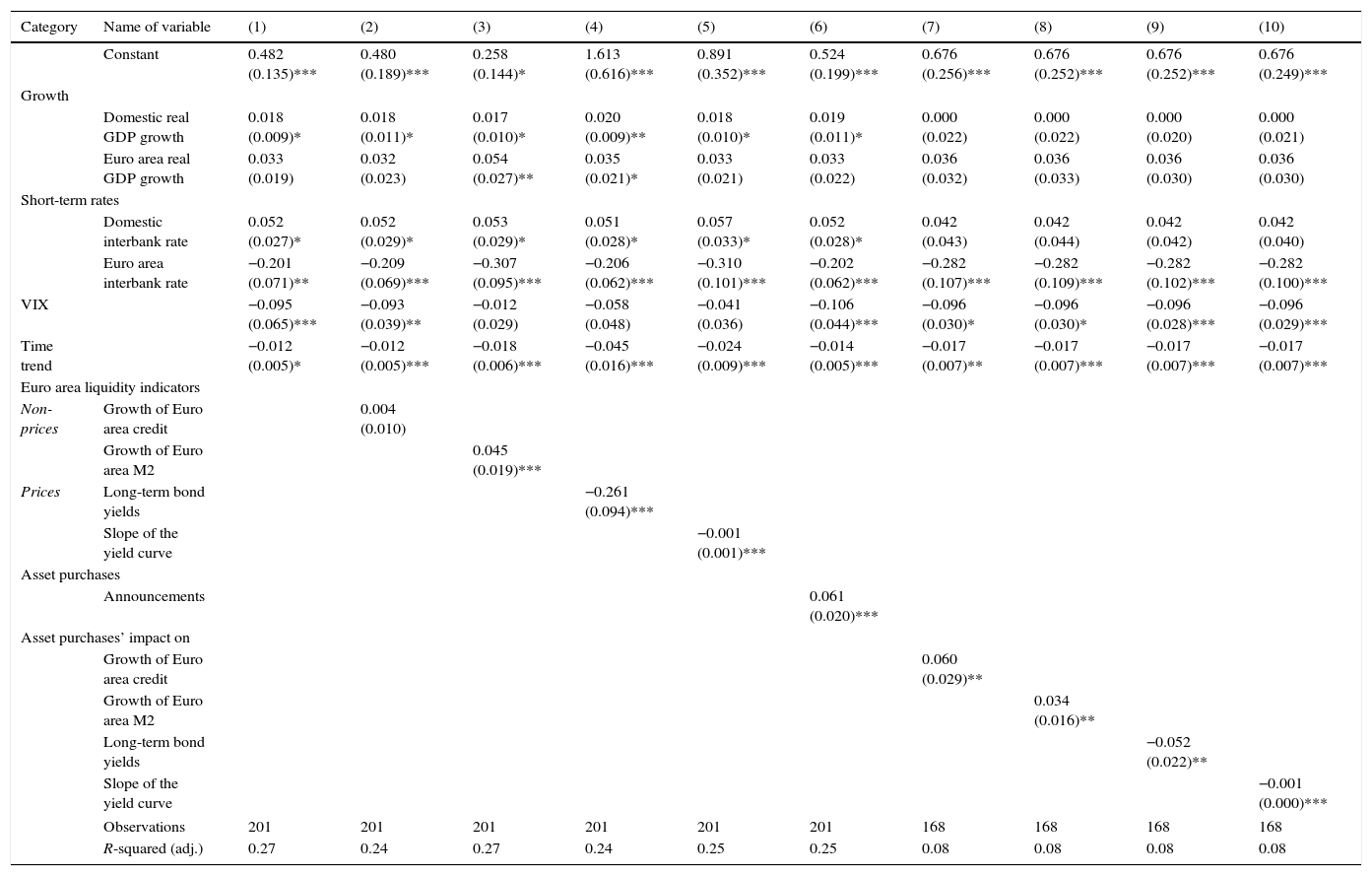

The portfolio rebalancing channel.

| Category | Name of variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.482 (0.135)*** | 0.480 (0.189)*** | 0.258 (0.144)* | 1.613 (0.616)*** | 0.891 (0.352)*** | 0.524 (0.199)*** | 0.676 (0.256)*** | 0.676 (0.252)*** | 0.676 (0.252)*** | 0.676 (0.249)*** | |

| Growth | |||||||||||

| Domestic real GDP growth | 0.018 (0.009)* | 0.018 (0.011)* | 0.017 (0.010)* | 0.020 (0.009)** | 0.018 (0.010)* | 0.019 (0.011)* | 0.000 (0.022) | 0.000 (0.022) | 0.000 (0.020) | 0.000 (0.021) | |

| Euro area real GDP growth | 0.033 (0.019) | 0.032 (0.023) | 0.054 (0.027)** | 0.035 (0.021)* | 0.033 (0.021) | 0.033 (0.022) | 0.036 (0.032) | 0.036 (0.033) | 0.036 (0.030) | 0.036 (0.030) | |

| Short-term rates | |||||||||||

| Domestic interbank rate | 0.052 (0.027)* | 0.052 (0.029)* | 0.053 (0.029)* | 0.051 (0.028)* | 0.057 (0.033)* | 0.052 (0.028)* | 0.042 (0.043) | 0.042 (0.044) | 0.042 (0.042) | 0.042 (0.040) | |

| Euro area interbank rate | −0.201 (0.071)** | −0.209 (0.069)*** | −0.307 (0.095)*** | −0.206 (0.062)*** | −0.310 (0.101)*** | −0.202 (0.062)*** | −0.282 (0.107)*** | −0.282 (0.109)*** | −0.282 (0.102)*** | −0.282 (0.100)*** | |

| VIX | −0.095 (0.065)*** | −0.093 (0.039)** | −0.012 (0.029) | −0.058 (0.048) | −0.041 (0.036) | −0.106 (0.044)*** | −0.096 (0.030)* | −0.096 (0.030)* | −0.096 (0.028)*** | −0.096 (0.029)*** | |

| Time trend | −0.012 (0.005)* | −0.012 (0.005)*** | −0.018 (0.006)*** | −0.045 (0.016)*** | −0.024 (0.009)*** | −0.014 (0.005)*** | −0.017 (0.007)** | −0.017 (0.007)*** | −0.017 (0.007)*** | −0.017 (0.007)*** | |

| Euro area liquidity indicators | |||||||||||

| Non-prices | Growth of Euro area credit | 0.004 (0.010) | |||||||||

| Growth of Euro area M2 | 0.045 (0.019)*** | ||||||||||

| Prices | Long-term bond yields | −0.261 (0.094)*** | |||||||||

| Slope of the yield curve | −0.001 (0.001)*** | ||||||||||

| Asset purchases | |||||||||||

| Announcements | 0.061 (0.020)*** | ||||||||||

| Asset purchases’ impact on | |||||||||||

| Growth of Euro area credit | 0.060 (0.029)** | ||||||||||

| Growth of Euro area M2 | 0.034 (0.016)** | ||||||||||

| Long-term bond yields | −0.052 (0.022)** | ||||||||||

| Slope of the yield curve | −0.001 (0.000)*** | ||||||||||

| Observations | 201 | 201 | 201 | 201 | 201 | 201 | 168 | 168 | 168 | 168 | |

| R-squared (adj.) | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | |

Note: The sample of 11 EMEs includes Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, FRY of Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania and Serbia, Bootstrapped (1000 replications) standard errors are provided in parenthesis, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, **p<0.1.

The results point to a significantly positive influence on portfolio flows from euro area financial and liquidity conditions, confirming the results of the extant literature (Cerutti et al., 2014; IMF, 2010). The coefficients of both M2 and private sector credit show the expected positive sign, the former being highly statistically significant. Similar conclusions hold for price indicators: a fall in euro area long term yields brings about larger portfolio flows to CESEE economies (as in Ahmed & Zlate, 2014); secondly, the negative sign for the coefficient of the yield curve slope would suggest that when euro area investment opportunities are more attractive, cross-border portfolio flows to CESEE countries decline (as in Cerutti et al., 2014).

Turning to the effect of the announcement of the ECB's asset purchase programmes, the coefficient of the dummy has the expected sign and is statistically significant, thus confirming the results of the previous event study analysis. Once the indicators of the actual financial and liquidity conditions are supplanted by their corresponding instrumented variables, their respective coefficients have the expected sign and are also highly statistically significant.25

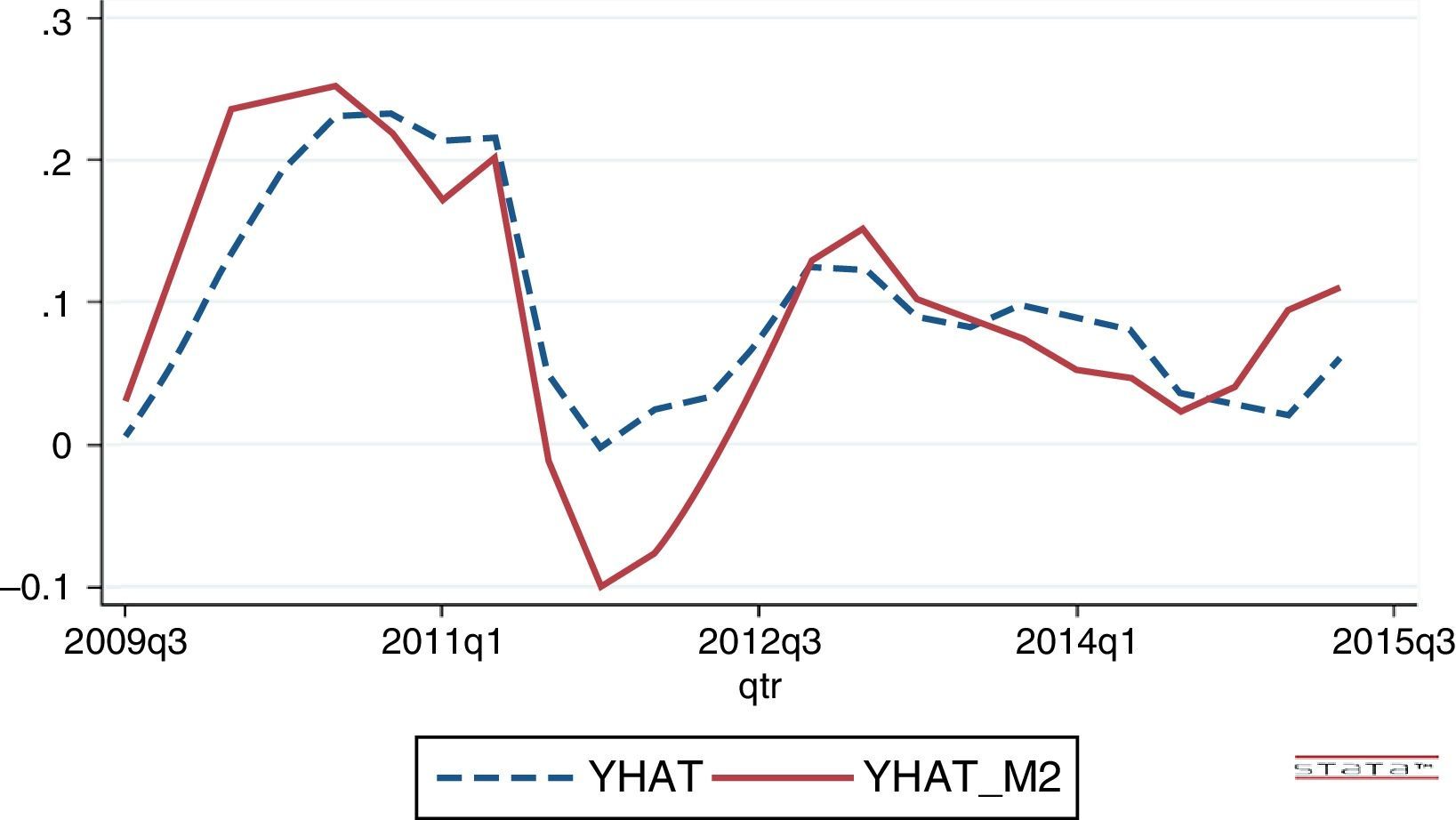

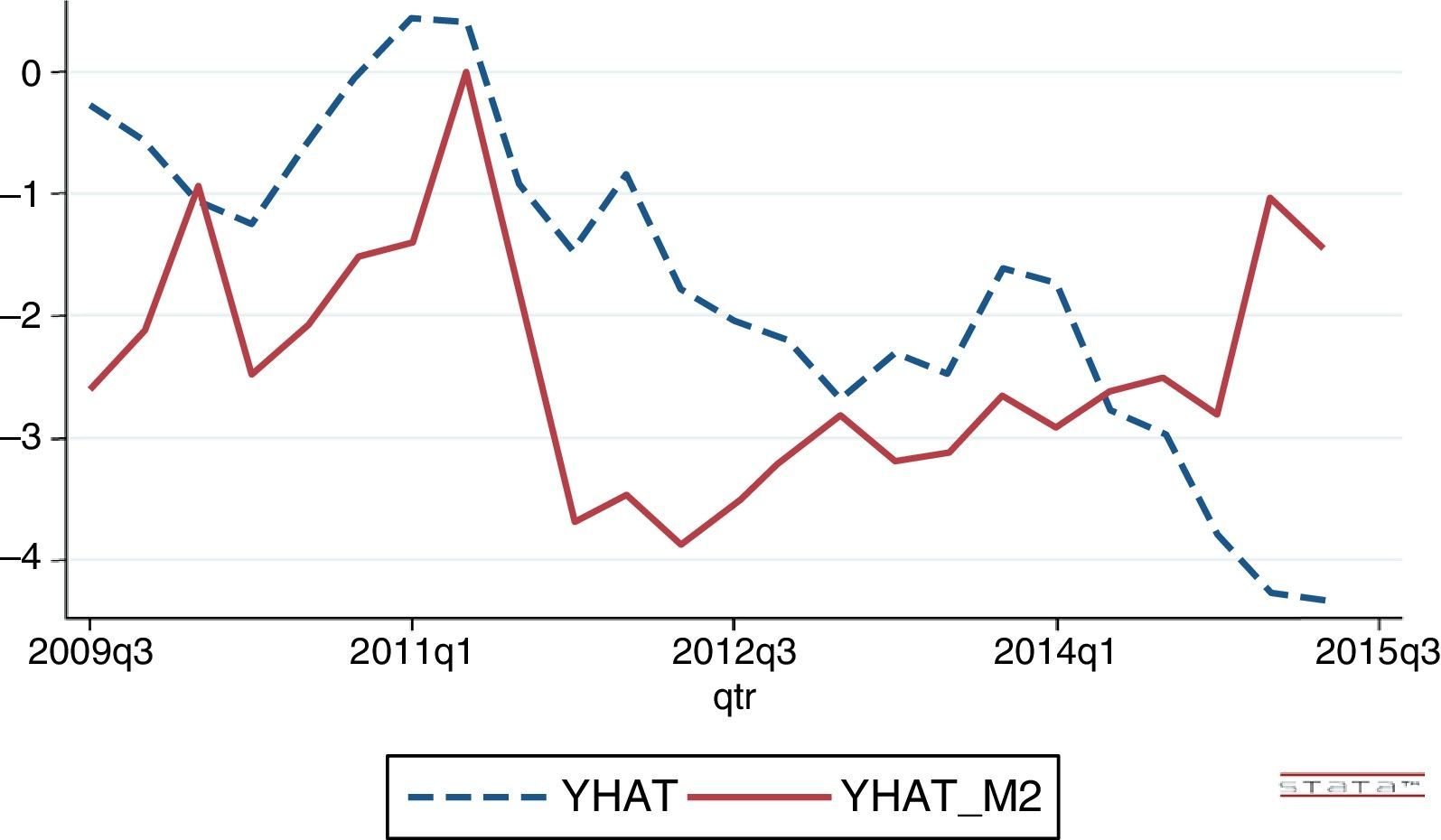

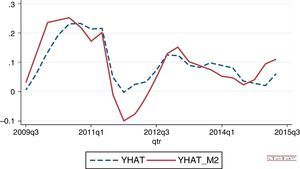

The coefficients given in Table 4 by themselves do not directly tell us the economic importance of the different variables implied by the estimated model. One way to gauge the relevance of a particular variable – from our point of view, the impact of the asset purchase programmes implemented by the ECB – would be to compare the fitted values from the full model with the model predictions under the counterfactual that keeps that particular explanatory variable of interest at a certain value, rather than allowing it to evolve as it did in reality. The two series depicted in Fig. 4, for instance, describe the results of this estimation exercise: the first one, labelled as YHAT, represents the quarterly country average of the fitted values stemming from the estimation results contained in column (1) of Table 4, i.e. a model for capital inflows to CESEE economies with no role for the impact of the ECB asset purchase programmes on euro area liquidity and financing conditions; the second series, labelled as YHAT_M2, represents, on the contrary, the quarterly country average of the fitted values stemming from the estimation results contained in column (8) of Table 4, i.e. a model for capital inflows to CESEE economies that accounts for the direct impact of the ECB's asset purchase programmes on euro area M2 growth. As the chart clearly shows, the impact of ECB's non-standard monetary measures on the dynamics of the M2 aggregate was an economically important determinant of capital flows to CESEE economies, helping to sustain them especially in the outer years, when the programme was gradually extended and enlarged.

Portfolio inflows: fitted vs counterfactual excluding ECB APP (quarterly data; %). Note: The fitted values and counterfactuals are based on the model with country fixed effects. The counterfactuals are the fitted values obtained under the assumption that the ECB APP variable was kept equal to zero over the whole estimation period.

Overall, these results support the conclusion that the ECB's asset purchase programmes tend to positively affect portfolio flows into CESEE countries both directly (based on their announcement effect) and indirectly (through their influence on our chosen set of indicators of euro area financial and liquidity conditions).

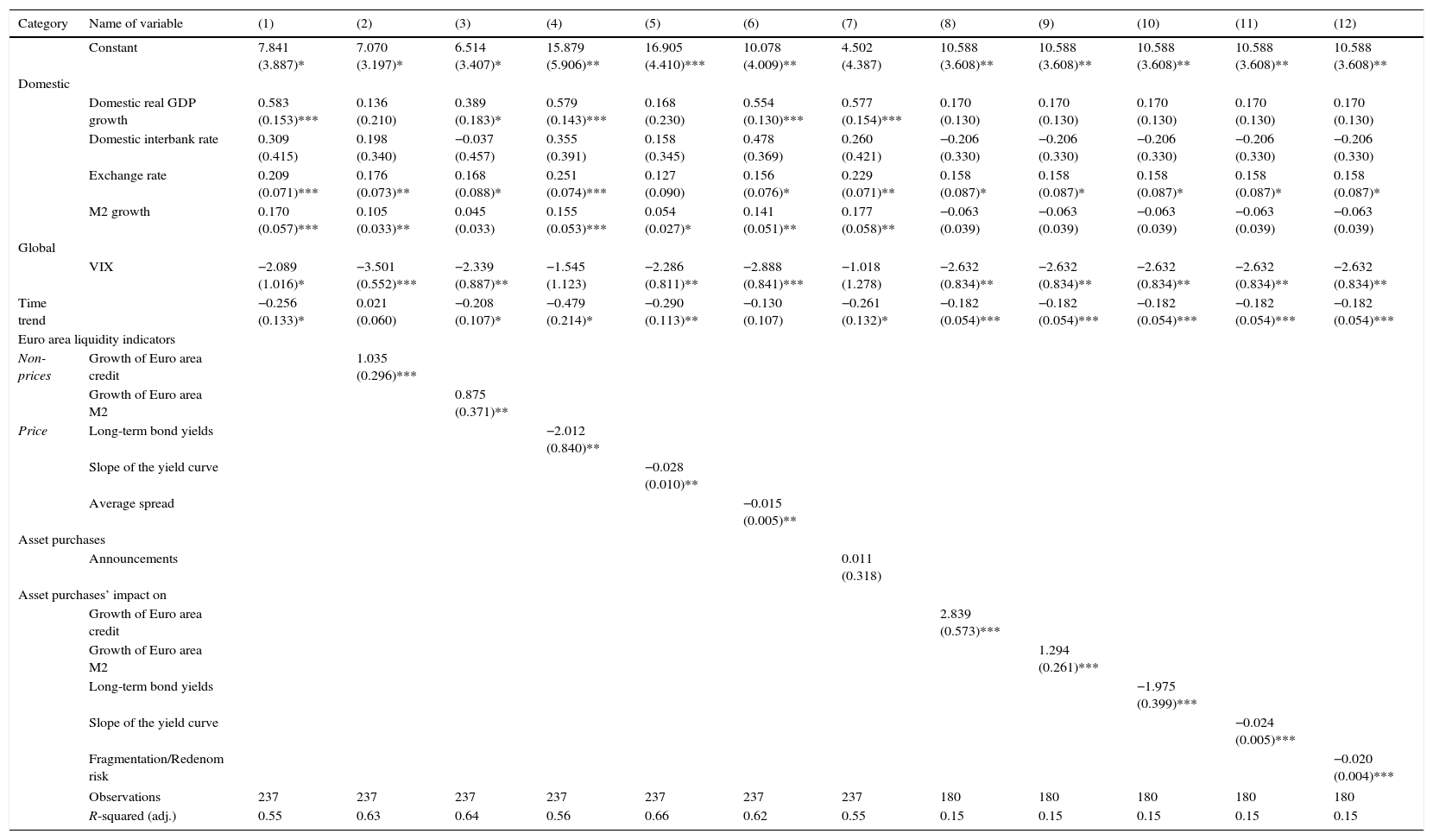

5.3The banking liquidity channelIn this section, we analyze another transmission channel through which the ECB's non-standard monetary measures might spread out to CESEE economies, by easing liquidity conditions for euro area international banks and influencing their decisions to extend cross-border lending abroad.

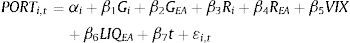

As was the case for the portfolio rebalancing channel, we complement a standard model of cross-border bank capital flows (Buch, Koch, & Koetter, 2009; García Herrero & Martínez Pería, 2005; Herrmann & Mihaljek, 2010; McGuire & Tarashev, 2008) – based upon a set of traditional control variables describing country-specific vulnerabilities and time-varying global financial conditions – with our set of variables measuring financial and liquidity conditions in the euro area, their instrumented counterparts, and the dummy indicator on the ECB's asset purchase programmes announcements.26 Cross-border banking flows, BANKi,t, will thus be explained by means of the following empirical model:

Given the constraint represented by the relatively small size of the sample, we start with a very simple specification, where international bank exposures from the BIS International Banking Statistics (IBS) are regressed on a set of domestic ‘pull’ factors, describing the main features of the receiving economy, and some measures of global conditions (countervailing ‘push’ determinants). More precisely, we assume that cross-border banking flows are positively related to: (i) the real GDP growth rate, since faster growing economies may have greater demand for credit, including from abroad (Bruno & Shin, 2015; Cerutti et al., 2014); (ii) a measure of domestic interest rate conditions, since countries characterized by higher interest rates attract more capital from abroad ceteris paribus (Bruno & Shin, 2015; Cerutti et al., 2014; Herrmann & Mihaljek, 2010); (iii) a measure of exchange rate conditions, since an appreciation in the local currency tends to translate into more capacity for local debtors to repay borrowing in foreign currency (Bruno & Shin, 2015; Herrmann and Mihaljek, 2010); (iv) the annual growth rate of the domestic money supply, a likely leading indicator of the health of the economy (Bruno & Shin, 2014); (v) the VIX index, in view of the strong commonality between international credit and portfolio flows and their synchronization with fluctuations in the global degree of risk aversion and uncertainty (Bruno & Shin, 2015; Rey, 2013, 2015). Finally, a time trend t is included in all our specifications.

Our results are based on an unbalanced, quarterly panel data set covering the 11 CESEE economies over the period 2008Q1–2015Q4. To mitigate possible endogeneity effects, all independent variables are lagged by one quarter (except the VIX, assumed to be exogenous). For the dependent variable, we use exchange rate-adjusted changes in the external exposures (loans, securities and other claims) of BIS reporting banks vis-à-vis both the banking and the non-banking sector in CESEE economies. As regards short-term interest rates, we again resorted to the 3-month interbank rates, which are more widely available for the countries in our sample. As regards the measure of exchange rate conditions, we use the nominal effective exchange rate.27

Column (1) in Table 5 shows the estimated coefficients of the basic model without liquidity indicators, which confirm our expectations about both the sign and the statistical and economic significance of the explanatory variables. Cross-border banking flows are a positive function of the growth of real GDP and the M2 aggregate, the appreciation of the domestic currency in nominal effective terms and the level of domestic interest rates (though this variable is not statistically significant). Finally, cross-border banking flows appear to be negatively related to international investors’ degree of risk aversion.

The banking liquidity channel.

| Category | Name of variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 7.841 (3.887)* | 7.070 (3.197)* | 6.514 (3.407)* | 15.879 (5.906)** | 16.905 (4.410)*** | 10.078 (4.009)** | 4.502 (4.387) | 10.588 (3.608)** | 10.588 (3.608)** | 10.588 (3.608)** | 10.588 (3.608)** | 10.588 (3.608)** | |

| Domestic | |||||||||||||

| Domestic real GDP growth | 0.583 (0.153)*** | 0.136 (0.210) | 0.389 (0.183)* | 0.579 (0.143)*** | 0.168 (0.230) | 0.554 (0.130)*** | 0.577 (0.154)*** | 0.170 (0.130) | 0.170 (0.130) | 0.170 (0.130) | 0.170 (0.130) | 0.170 (0.130) | |

| Domestic interbank rate | 0.309 (0.415) | 0.198 (0.340) | −0.037 (0.457) | 0.355 (0.391) | 0.158 (0.345) | 0.478 (0.369) | 0.260 (0.421) | −0.206 (0.330) | −0.206 (0.330) | −0.206 (0.330) | −0.206 (0.330) | −0.206 (0.330) | |

| Exchange rate | 0.209 (0.071)*** | 0.176 (0.073)** | 0.168 (0.088)* | 0.251 (0.074)*** | 0.127 (0.090) | 0.156 (0.076)* | 0.229 (0.071)** | 0.158 (0.087)* | 0.158 (0.087)* | 0.158 (0.087)* | 0.158 (0.087)* | 0.158 (0.087)* | |

| M2 growth | 0.170 (0.057)*** | 0.105 (0.033)** | 0.045 (0.033) | 0.155 (0.053)*** | 0.054 (0.027)* | 0.141 (0.051)** | 0.177 (0.058)** | −0.063 (0.039) | −0.063 (0.039) | −0.063 (0.039) | −0.063 (0.039) | −0.063 (0.039) | |

| Global | |||||||||||||

| VIX | −2.089 (1.016)* | −3.501 (0.552)*** | −2.339 (0.887)** | −1.545 (1.123) | −2.286 (0.811)** | −2.888 (0.841)*** | −1.018 (1.278) | −2.632 (0.834)** | −2.632 (0.834)** | −2.632 (0.834)** | −2.632 (0.834)** | −2.632 (0.834)** | |

| Time trend | −0.256 (0.133)* | 0.021 (0.060) | −0.208 (0.107)* | −0.479 (0.214)* | −0.290 (0.113)** | −0.130 (0.107) | −0.261 (0.132)* | −0.182 (0.054)*** | −0.182 (0.054)*** | −0.182 (0.054)*** | −0.182 (0.054)*** | −0.182 (0.054)*** | |

| Euro area liquidity indicators | |||||||||||||

| Non-prices | Growth of Euro area credit | 1.035 (0.296)*** | |||||||||||

| Growth of Euro area M2 | 0.875 (0.371)** | ||||||||||||

| Price | Long-term bond yields | −2.012 (0.840)** | |||||||||||

| Slope of the yield curve | −0.028 (0.010)** | ||||||||||||

| Average spread | −0.015 (0.005)** | ||||||||||||

| Asset purchases | |||||||||||||

| Announcements | 0.011 (0.318) | ||||||||||||

| Asset purchases’ impact on | |||||||||||||

| Growth of Euro area credit | 2.839 (0.573)*** | ||||||||||||

| Growth of Euro area M2 | 1.294 (0.261)*** | ||||||||||||

| Long-term bond yields | −1.975 (0.399)*** | ||||||||||||

| Slope of the yield curve | −0.024 (0.005)*** | ||||||||||||

| Fragmentation/Redenom risk | −0.020 (0.004)*** | ||||||||||||

| Observations | 237 | 237 | 237 | 237 | 237 | 237 | 237 | 180 | 180 | 180 | 180 | 180 | |

| R-squared (adj.) | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

Note: The sample of 11 EMEs includes Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, FRY of Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania and Serbia, Robust standard errors are provided in parenthesis, ***p<0.01, **p<0.05, **p<0.1.

We then add, one by one, all our variables of interest: the financial and liquidity conditions in the euro area, with the results reported in columns (2)–(6) of Table 5, the dummy indicator, in column (7) and the instrumented indicators, in columns (8)–(12), and the following conclusions stand out. Firstly, cross-border banking flows towards CESEE economies seem to be positively related, as expected, to the two measures of non-price liquidity conditions, i.e. euro area private sector credit and M2 dynamics. Secondly, the coefficient of the average spread of stressed peripheral euro area countries vis-à-vis the German Bund is negative and statistically significant, suggesting that fragmentation and redenomination risks have brought about a reduction in cross-border banking flows towards CESEE economies. The euro area yield curve slope comes in again with a negative coefficient, as in Cerutti et al. (2014), hinting that when euro area investment opportunities are more attractive, cross-border banking flows decline. Lastly, a fall in euro area long-term yields is estimated to bring about larger cross-border banking flows to CESEE economies. Turning to the announcement episodes captured by the dummy indicator, the related coefficient suggests a positive impact on banking flows, though it comes out as not being statistically significant. Finally, once all the indicators of actual liquidity and financial conditions in the euro area are supplanted by their instrumented counterparts, their respective coefficients have the expected sign and are all statistically significant at conventional levels.

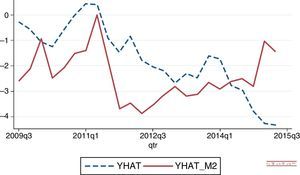

Since the coefficients in Table 5 have the same shortcomings as those in Table 4, we here perform again a counterfactual exercise to evaluate the effectiveness of the ECB's asset purchase programmes for cross-border banking flows towards CESEE economize. In doing so, we follow the same strategy laid out in Para 5.2. Fig. 5 reports two time series, YHAT and YHAT_M2. The first one is the quarterly country average of the fitted values stemming from a model for banking inflows to CESEE economies with no role for the impact of the ECB's asset purchase programmes on euro area liquidity and financing conditions (i.e. the estimation results contained in column (1) of Table 5); YHAT_M2, represents, on the contrary, the quarterly country average of the fitted values stemming from a model for banking inflows to CESEE economies that accounts for the direct impact of the ECB's asset purchase programmes on euro area M2 growth (the coefficients reported in column (9) of Table 5). Like in the case for portfolio inflows, the impact of ECB's non-standard monetary measures on the dynamics of the M2 aggregate was an economically significant determinant of banking flows to CESEE economies, helping to sustain them especially in the outer years on occasions of the gradual enhancement of the programme.

Cross-border banking flows: fitted vs counterfactual excluding ECB APP (quarterly data; %). Note: The fitted values and counterfactuals are based on the model with country fixed effects. The counterfactuals are the fitted values obtained under the assumption that the ECB APP variable was kept equal to zero over the whole estimation period.

All in all, the more accommodative financial and liquidity conditions in the euro area resulting from the actual implementation of the ECB's asset purchase programmes, along with the easing of the tensions on the sovereign spreads of peripheral euro area countries, seem to have had an overall positive effect on cross-border banking flows towards CESEE economies.

6ConclusionsConsistently with the findings of the empirical literature on the international effects of the unconventional monetary measures adopted by central banks in AEs, we have shown that the ECB's asset purchase programmes announced and implemented over the past five years have had significant short and long term spillover effects on asset prices in and cross-border capital flows to eleven CESEE countries. As regards the short term effect, on the eighteen occasions where the ECB made some announcements on new or existing asset purchase programmes there was a statistically discernible impact on CESEE financial variables (e.g., weekly movements of the exchange rate vis-à-vis the euro, domestic stock market indices, long term sovereign yields, and also on weekly portfolio flows towards CESEE countries).

We have also extended our analysis to a longer time horizon through more articulated models of portfolio and international banking flows. Within these frameworks, we have found that both types of capital flows towards CESEE economies have been sustained by both the announcement and the actual implementation of the ECB's asset purchases programmes. This evidence points to the existence of positive international spillover effects through both a portfolio rebalancing and a banking liquidity channel.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the editor, two anonymous referees, Giuseppe Parigi, Pietro Catte, Valeria Rolli, Emidio Cocozza and Martina Cecioni for their helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this paper. The usual disclaimers apply.

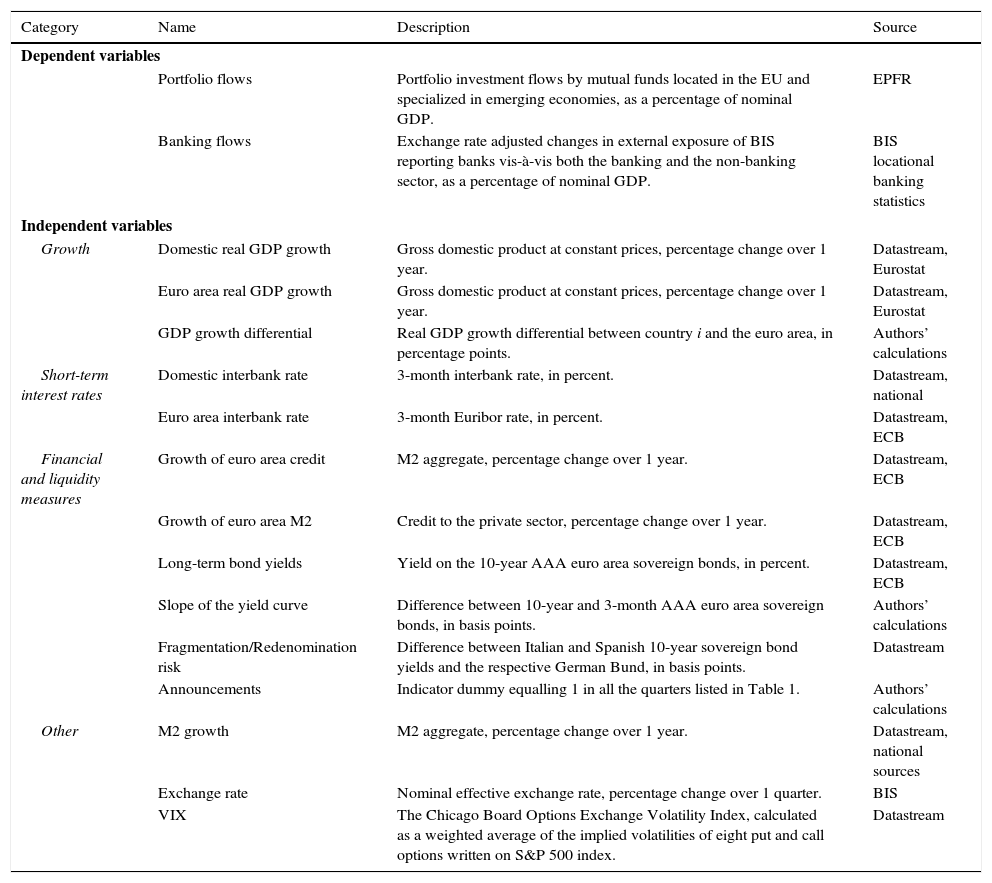

| Category | Name | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||

| Portfolio flows | Portfolio investment flows by mutual funds located in the EU and specialized in emerging economies, as a percentage of nominal GDP. | EPFR | |

| Banking flows | Exchange rate adjusted changes in external exposure of BIS reporting banks vis-à-vis both the banking and the non-banking sector, as a percentage of nominal GDP. | BIS locational banking statistics | |

| Independent variables | |||

| Growth | Domestic real GDP growth | Gross domestic product at constant prices, percentage change over 1 year. | Datastream, Eurostat |

| Euro area real GDP growth | Gross domestic product at constant prices, percentage change over 1 year. | Datastream, Eurostat | |

| GDP growth differential | Real GDP growth differential between country i and the euro area, in percentage points. | Authors’ calculations | |

| Short-term interest rates | Domestic interbank rate | 3-month interbank rate, in percent. | Datastream, national |

| Euro area interbank rate | 3-month Euribor rate, in percent. | Datastream, ECB | |

| Financial and liquidity measures | Growth of euro area credit | M2 aggregate, percentage change over 1 year. | Datastream, ECB |

| Growth of euro area M2 | Credit to the private sector, percentage change over 1 year. | Datastream, ECB | |

| Long-term bond yields | Yield on the 10-year AAA euro area sovereign bonds, in percent. | Datastream, ECB | |

| Slope of the yield curve | Difference between 10-year and 3-month AAA euro area sovereign bonds, in basis points. | Authors’ calculations | |

| Fragmentation/Redenomination risk | Difference between Italian and Spanish 10-year sovereign bond yields and the respective German Bund, in basis points. | Datastream | |

| Announcements | Indicator dummy equalling 1 in all the quarters listed in Table 1. | Authors’ calculations | |

| Other | M2 growth | M2 aggregate, percentage change over 1 year. | Datastream, national sources |

| Exchange rate | Nominal effective exchange rate, percentage change over 1 quarter. | BIS | |

| VIX | The Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index, calculated as a weighted average of the implied volatilities of eight put and call options written on S&P 500 index. | Datastream | |

Throughout the paper we will refer indifferently to the ECB's or the Eurosystem's non-standard tools while such measures are actually decided and implemented by the Eurosystem as a whole.

CESEE economies are made up of both non-euro area EU countries – Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania – and EU candidates and potential candidates – Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, the FYR of Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia.

In the extant literature there is a very long series of transmission channels. To name but a few examples: Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen (2011) proposed a duration risk channel, a safety channel, a prepayment risk premium channel, a default risk channel and an inflation channel; Fratzscher et al. (2014) added a risk aversion channel, a bank credit risk channel and a sovereign credit risk channel; Cova and Ferrero (2015) an asset pricing channel and a government budget constraint channel.

They estimate the effects of the announcement dates associated with the first rounds of the two Fed's unconventional measures: QE1 – which traditionally refers to the period immediately after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 – and QE2 – which refers to the further push implemented by the Fed from the second half of 2010, primarily concentrated on purchases of US Treasury securities.

The authors link these results to the working of many different transmission channels: the role of the US term structure in setting a benchmark for global assets, a confidence channel reflecting perceptions of the strength of the global economy and an endogenous monetary policy response channel aimed at narrowing international policy rate differentials.

By applying factor analysis in order to disentangle a ‘signal’ (assumed to affect expectations of future short-term policy rates) from a ‘market’ factor (assumed to affect longer-term rates through a variety of channels) in the conduct of US monetary policy, the authors showed how spillovers have been different and stronger during the unconventional monetary phase (i.e. from November 2008 onwards) than previously.

The liquidity channel is proxied by the 3-month Treasury bill rate; the portfolio rebalancing channel by the term spreads and the interest rate differential between developing countries and the US; the confidence channel by the VIX index.

According to their estimation results, of the 62% increase in overall gross inflows to EMEs observed between 2009 and 2013, at least 13% can be attributed to this additional QE effect.

In the earlier phases, non-standard monetary policy measures were directly targeting markets essential for commercial banks’ funding, with the explicit aim of restoring proper liquidity conditions that had been impaired by the global financial crisis. Against a background of severe stress in the interbank markets due to solvency concerns, widespread financial uncertainty and liquidity hoarding by market participants, some of the measures introduced by the ECB were: (a) unlimited provision of liquidity through ‘fixed rate tenders with full allotment’, allowing banks unlimited access to central bank liquidity at the main refinancing rate, subject to appropriate collateral; (b) a broadening of the list of eligible collateral assets for refinancing operations; (c) an extension of the maturity (to 6 months) of long-term refinancing operations (LTROs), to reduce uncertainty and improve liquidity conditions for banks; (d) liquidity provision in foreign currencies through swap lines with other central banks.

The CBPP1 ended, as planned, on 30 June 2010 when it reached the originally announced target of €60 billion in nominal terms. The CBPP2 terminated on 31 October 2012 when it reached a nominal amount of €16.4 billion, below the original targeted amount of €40 billion. The CBPP3, on the contrary, was not launched with a pre-fixed targeted nominal amount; as a matter of fact, as of 13th May 2016, it reached €175.3 billion.

EPFR collects and aggregates data on the investment activity of a large number of individual funds specialized in asset allocation towards the countries belonging to our sample (among others). In particular, we focus our attention on the share of individual funds originating in the European Union because they are more likely to be affected by the ECB's decisions.

To measure economic surprises we rely on the Citigroup Economic Surprise Indices, which are commonly regarded as objective and quantitative measures of economic news. They are calculated as the normalized deviation of the actual data release from the market consensus prior to the release (actual releases vs. the Bloomberg survey median). A positive reading of the Economic Surprise Index suggests that economic releases have on balance been beating consensus. The indices are calculated daily in a rolling three-month window. The weights of economic indicators are derived from the relative high-frequency spot FX impacts of 1 standard deviation data surprises. The indices also employ a time decay function to replicate the limited memory of markets.

As for event study analysis related to portfolio flows, both the Citigroup Economic Surprise indices and the VIX are end-of-period data, recorded and reported on Fridays, while portfolio inflows are released and recorded on Wednesdays and refer to the seven days including the reporting day.

As a robustness check we have also run the same set of regressions with 2-day and 1-week window. Results are broadly consistent with those reported in the main text and are available from the authors upon request.

Although the assumption in the literature has been that factors driving global liquidity originate predominantly in the US, some recent results (Cerutti et al., 2014; Korniyenko and Loukoianova, 2015) suggest that euro area supply factors are both regionally and globally important too.

According to Casiraghi, Gaiotti, Rodano, and Secchi (2013), the asset purchases implemented under the SMP – which is a component of our sample of non-standard monetary measures – appear to have been effective in offsetting unjustified increases in government bond yields and easing money market tensions, with a positive and significant impact on credit supply. We tried two other indicators for the fragmentation of the banking sector: (i) the euro area version of the 3-month LIBOR-OIS spread, a barometer of distress in money markets, which has served as a summary indicator showing the ‘illiquidity waves’ that severely impaired money markets in 2007 and 2008; (ii) the average of 5-year CDS premia in Italy and Spain. However, econometric estimates with these variables (available upon request) do not show any significant results.

The regressions have been performed on a monthly frequency for the credit and the M2 growth rates, and on weekly frequency for long-term yields, slope of the yield curve and the yield differential with the German bund.

Moreover, resorting to the one-quarter ahead ECB's actual gross asset purchases helps to get rid of any likely endogeneity issue related to the bivariate relationship with financial and liquidity indicators.

A principal component analysis among the whole series of financial and liquidity indicators showed that the first factor explains more than 70% of the total covariance. A successive OLS regression revealed that the ECB's gross asset purchases are a significant determinant for this first principal component.

Evidence on the latter topic can mostly be inferred from research on the effects of long-term US interest rates (or other proxies for global interest rates and liquidity conditions) during the pre-crisis period, while non-standard measures more recently used by AE central banks have rarely been included. Notable exceptions are represented by Moore et al. (2013) and Fratzscher, Lo Duca, and Straub (2012), Fratzscher, Lo Duca, and Straub (2013) and Fratzscher et al. (2014).

A detailed description of this model, highlighting how it could also be applied to identify a set of ‘push’ and ‘pull’ determinants of portfolio flows towards CESEE economies is available from the authors upon request. The Appendix contains a description of the main variables used for estimation purposes.

The expected signs are as follows: (i) as regards growth, we expect a positive β1, since a healthier economy is expected to attract larger inflows of capital, while the sign of β2 is not unambiguously defined ex-ante, since stronger growth in the euro area might drive more capital abroad as well; (ii) as regards interest rate conditions, β3 and β4 should have opposing signs, since higher interest rates in EMEs can attract capital inflows related, for instance, to carry-trade positions being undertaken or, by the same token, a decline in AEs interest rates would prompt investors to rebalance their portfolios towards higher-yielding assets, thus resulting in capital flows into EMEs; (iii) β5 should be negative, since a surge in volatility would prompt international investors to display typical ‘risk-off’ behaviour. It is also important to recollect that the VIX index, as well as other volatility indicators, has been used in the extant empirical literature as an explicit indicator for the unfolding of the ‘signalling’ and ‘confidence’ effect (Lim et al., 2014); moreover, it has been shown how the ECB's non-standard policies have had a positive (i.e. decreasing) effect on this volatility indicator, as well as on other ones (Fratzscher et al., 2014; Georgiadis & Gräb, 2015).

We also estimated alternative a model based on policy interest rates, but this was not able to beat the results obtained with the specification reported in the main text in terms of R-squared and the sign and significance of the coefficients. The model is available from the authors upon request.

Portfolio inflows towards CESEE economies appear to be positively related to stronger growth realizations both domestically and in the euro area, although the latter are not statistically significant. More relevant contributions to the explanation of the dynamics of portfolio flows stem from interest rate conditions, where the magnitudes of the estimated effects appear to be economically significant as well: a one percentage point increase in domestic short-term rates in the CESEE economies would be associated with additional portfolio inflows of 0.05% of GDP, while the same increase in euro area short-term rates would lead to a net outflow of 0.21% of GDP. Confirming the results in the literature, greater global risk aversion has a significantly negative effect on portfolio inflows towards CESEE economies, from both a statistical and an economic perspective.