Among the numerous polities of the Usumacinta region, Toniná stands as the worst defined. In spite of its reduced population, Toniná developed an aggressive policy, and won several victories upon close-by and distant cities as well. This article tries, from the available archaeological and epigraphic data, to draw a more precise definition of the Toniná polity and socio-political structure, in order to interpret the city long-lasting success.

Entre las numerosas entidades de la Cuenca del Usumacinta, Toniná resulta la peor definida. A pesar de su población reducida, Toniná desarolló una política agresiva, logrando varias victorias sobre ciudades vecinas y lejanas. Este artículo busca, a partir de los datos arqueológicos y epigráficos disponibles, establecer una definición más precisa de su territorio y su estructura sociopolítica, y entender las razones de sus éxitos.

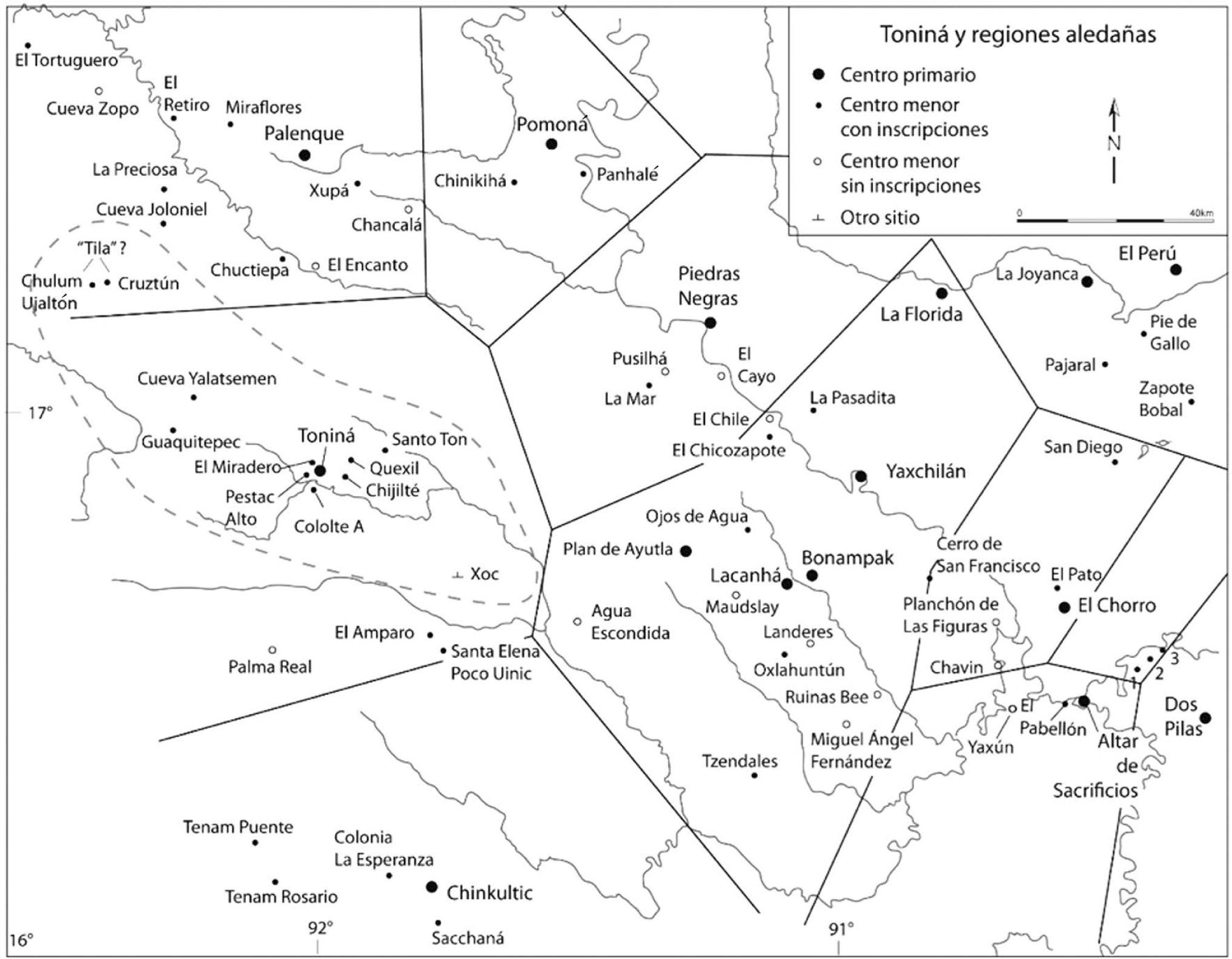

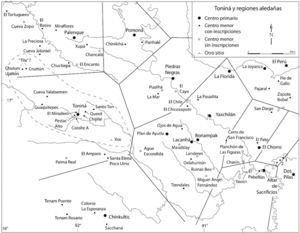

Basing his analysis upon the presence of emblem glyphs, available epigraphic data and documented knowledge about the established relationships between the different Maya capitals, Mathews (1997) proposed a rather empirical definition of Classic period Maya political entities. Such polities are in most instances not defined by true or natural frontiers, but rather by imprecise, somewhat arbitrary limits. It is worth mentioning here that, in agreement with Rands’ ceramic data (1967), Mathews suggested that the Río Tulija, halfway between Palenque and Toniná, almost formed a true natural frontier. A preliminary definition of the Toniná polity had previously been suggested through a regional survey (Becquelin and Taladoire, 1990), but Mathews’ proposal stems from different basis. While most polities cover a mean area of 2500km2, the Toniná territory looks larger than most others (map 1). Palenque and Pomoná territories would respectively border it to the north and northeast. Piedras Negras and Bonampak entities define its eastern limits. To the south, it is still debatable if the nearest neighbour would be Chinkultic or the ill-known site of Santa Elena Poco Uinic, first discovered by Palacios (1928). In spite of his short visit to this later site, Mathews (2009) left the question open to discussion, but if such were the case, Toniná territory would be somewhat smaller.

Proposed Toniná polity (after Mathews, 1997).

Obviously, defining Maya polities on the basis of territoriality is somewhat an anachronism, since it is quite probable that, rather than arbitrary or natural frontiers and control of land and arable soils, they relied mostly upon socio-political relationships: allegiance of local elites to the main ruler, family ties, prestigious resources and population control or political rivalries (Golden y Scherer, 2013). It is thus necesary to consider epigraphic and iconographic data as well as archaeological or geographic evidences.

Previous attempts to define Maya polities relied upon scattered data and insufficient epigraphic records, hence numerous imprecisions in territorial delimitations, which obviously also changed through time. Marcus (1976) even included Toniná in the Palenque sphere. In other publications (Steward, 2009, e.g.), the Toniná sub-region frequently includes all the Chiapas Highlands sites. While such sites as Santo Ton, Guaquitepec and maybe El Amparo obviously pertain to the Toniná polity, others like Chinkultic, La Esperanza or Tenam Puente were certainly independent from Toniná. On the contrary, Tila, generally interpreted as a Palenque satellite, is often considered as pertaining to the Usumacinta sub-region (Steward, 2009).

The last researches in this still ill known part of Chiapas have brought to light more data, but unfortunately, we still lack a reliable study of existing monuments. As a matter of fact, Schele (1991) plainly regretted the limited amount of epigraphic inscriptions and decipherments, as well as of archaeological investigations. Mathews’ visit to Santa Elena Poco Uinic allowed him to identify, albeit as a preliminary proposal, a local ruler, Yax B’alam, born A.D. 766 (?), who ruled from 782 to 790 (Mathews, 2009). Beside Chinkultic, which is rather well studied, the last excavations in Tenam Rosario (de Montmollin, 1989), Tenam Puente (Lalo Jacinto and Aguilar, 1993) and the Las Margaritas region (Álvarez C., 1993; Álvarez, Lowe and Pérez Suárez, 1996) brought to light new monuments, and largely modified our knowledge of the Comitán region. Whether Plan de Ayutla corresponds to Sak Tzi or not, its identification would also reduce the Toniná direct sphere of influence (Biró, 2004; Anaya, Guenter and Zender, 2003). The greatest incognita remains the relationships of Toniná with its northern and western borders, i.e. with the neighbouring Chiapas highlands (Culbert, 1965; Paris, Taladoire and Lee Jr., in press). Only an intensive, systematic survey of the Oxchuc valley, where Blom (archives, Na Bolom) registered scattered prehispanic vestiges, and of the Bachajón-Chilón-Tila area might contribute to clarify this point. The issue is thus the definition of the extent of the Toniná polity, its demographic background, the nature of its internal political organization and, finally, our understanding of Toniná external policy and enmity towards many other cities.

How did Toniná manage to win so many victories against Palenque, Sak Tzi, Bonampak and various other cities, given its marginal situation and its relatively reduced population? The preliminary analysis of the Ocosingo valley settlement pattern (Becquelin and Taladoire, 1990) allowed the identification of some 260 residential platforms for the Late Classic Ixim phase (Table 1), beside Toniná proper. A later complementary survey in 1993 (Becquelin, Michelet and Taladoire, 1994) led to an augmentation by 42% of the total number of residential platforms, i.e. 370. To make comparisons easier, we shall use the estimate of 5.6 inhabitants per platform, as discussed by Becquelin and Michelet at Xculoc (1994), and Breton (1979) at Bachajón. It differs significantly from the usual ratio of 5.6 persons per house, with an estimation of three persons per house in Bachajón to 3.4 in the Puuc. However, the usual ratio gives us a total of 2070 inhabitants in the valley, to which we must add the Toniná inhabitants, which were estimated at 900, i.e. a little less that 3000 inhabitants in the valley.

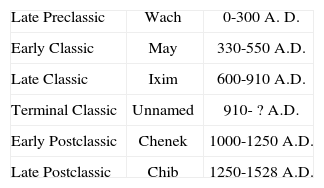

Schematic Toniná ceramic sequence. The Wach phase might start earlier, but up to now, no evidence has been recorded. Important Terminal Classic activities took place, such as building and reoccupation, but they are still insufficiently documented to define a ceramic phase.

| Late Preclassic | Wach | 0-300 A. D. |

| Early Classic | May | 330-550 A.D. |

| Late Classic | Ixim | 600-910 A.D. |

| Terminal Classic | Unnamed | 910- ? A.D. |

| Early Postclassic | Chenek | 1000-1250 A.D. |

| Late Postclassic | Chib | 1250-1528 A.D. |

Recent researches at Toniná proper (Yadeun, 2008) allow larger estimations, but Toniná presently includes what we considered as separated groups (such as Miradero, Toniná Bajo or Toniná Alto).

Thus, a larger demographic estimation for Toniná would lead to a consecutive reduction of the number of registered platforms in minor groups, in the Ocosingo valley. This gives us a population density of about 29h/km2. In comparison with Copán (84h/km2) or Nohmul (67h/km2, 6000 inhabitants) (Culbert and Rice, 1990), the Ocosingo valley looks scantily occupied. It is thus difficult to understand how such a reduced population could muster the armies to win such victories, even if Toniná could rely on the help of satellites sites. However, recent research in the Palenque area (Liendo Stuardo, 2001) suggests more balanced forces: Liendo Stuardo's estimates for Palenque proper during the Otolúm-Murciélagos (A.D. 650-750) y Balunté (A.D. 750-850) phases rise to some 6000 to 8000 inhabitants (Liendo Stuardo, 2011: 78), but for the 40km2 surrounding the city, he estimates a 25h/km2 density during the Balunté phase, which is comparable to the population density estimates for Toniná. Thus, while Palenque proper is obviously larger than Toniná, the difference is not so important as to impede any surprise raid or victory from the later.

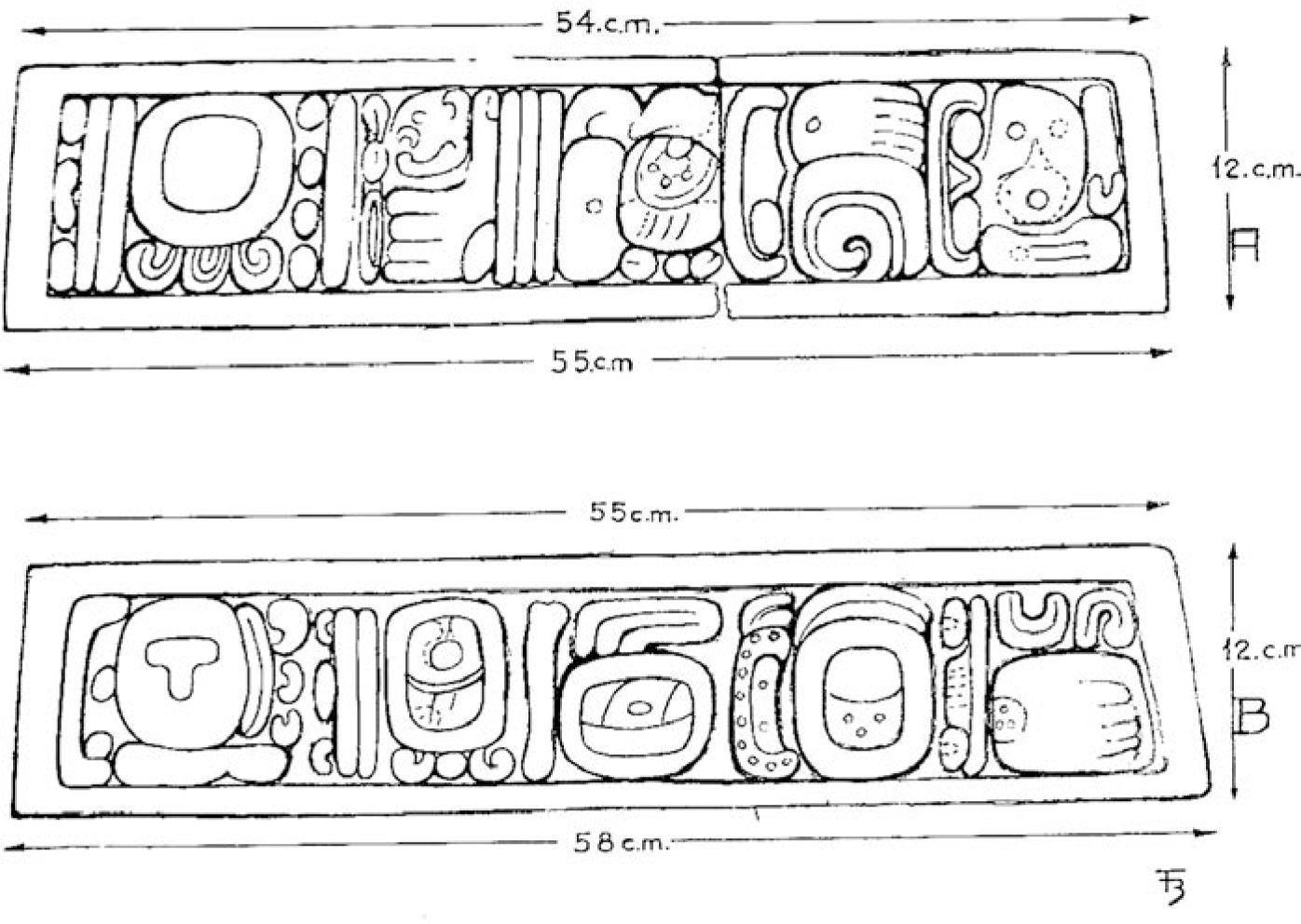

We must also consider that the Toniná polity was not restricted to the Ocosingo valley. It is necessary to proceed to a systematic evaluation of available data on possibly related sites with the Toniná polity. In order to complement the Toniná valley reconnaissance and obtain a better understanding of its territory, Becquelin (Becquelin and Baudez, 1982) surveyed in 1977 the Chilón-Bachajón region. This project stemmed directly from the presence at Guaquitepec of two monuments that present a close relationship with the Toniná sculptural style (Mayer, 1991) (figure 1). The Toniná emblem glyph has been recorded on one of those monuments. Beside three Early Postclassic sites, Becquelin registered six Late Classic sites, one of which, San Marcos, provided ceramic material from the Toniná Late Classic Ixim phase. He also rediscovered the 10 painted glyphs from the Yaleltsemen cave, and stucco modelled glyphs in Naxtenxum. We may then consider that the Chilón-Bachajón area pertained to the Toniná political entity. What about other sites? We can summarize the available data.

The Bachajón Zone: 4 sites and Yaleltsemen cave (Becquelin and Baudez, 1982)Oxyoket: Southwest of Bachajón. Six structures, including a small pyramid. Early Postclassic.

Najtil Cruz: On top of a ridge, west of Bachajón. Five structures and one pyramid.

Goloton: An isolated platform, west of Bachajón.

Jetchja: No description. One Fine Orange sherd (Pabellon type). Terminal Classic(?).

Yaleltsemen cave: The Late Classic paintings represent a sitting young lord, with a ten glyphs inscription. According to Mathews, while the inscription does not refer to Toniná, it includes the glyph of Sib’ikté, this identification being confirmed by David Stuart (K. Bassie-Sweet, pers. com., 2000). Late Classic.

The Sitala-Guaquitepec Zone: 5 sites, and the Guaquitepec Monuments (Becquelin and Taladoire, 1990)Guaquitepec: Two monuments in town, one of them with the Toniná emblem-glyph (Mayer, 1991). Since no ruins have ever been located at Guaquitepec proper, both monuments could come from any nearby site.

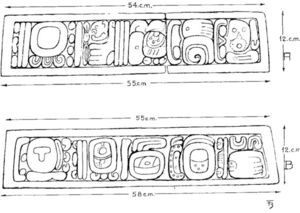

M1: In the round sandstone statue of a standing dignitary. Glyphs on the pedestal (figure 1) and in a double row on the back. H: 116 cm.

M2: Sandstone disk with a row of glyphs on the periphery (figure 1). D: 116 cm.

Peña Fuerte: 2km south of Guaquitepec. This site is registered, but has not been surveyed. Tombs, ruins. Sherds in a nearby cave.

Bolonchan: A small mound on a ridge, north of Sitala. Numerous tombs. Ruins. Blom (1961) mentioned a possible monument.

La Ceiba: Four platforms on top of a hill, west of Sitala.

San Marcos: Southeast of Guaquitepec. A group of seven structures including a pyramidal mound. Toniná Ixim phase ceramics and some Chenek sherds. Late Classic-Early Postclassic.

Sitala: An unrecorded site, east of Sitala.

The Chilón Zone: 8 sites (Becquelin and Baudez, 1982)G. Duby, who visited the area in 1958, registered several sites on top of small hills, east of Chilón, to which she gave the global name of Nahtomtzum-Na Cho-Muctana, sometimes spelled as Natenzun-Na Cho’j-Muktenah. Duby already mentioned important looting, but she also registered paintings in a tomb (Piña Chan, 1967).

Naxtenxum: Six small platforms on top of a ridge. Stucco fragments: glyphs. Looted tombs. Late Classic-Early Postclassic. The tomb mentioned by Duby probably corresponds to this site. The standing buildings display Late Classic architectural decorations and hieroglyphs (Bassie-Sweet et al., in prep.).

Nachoj A: A single structure on top of a hill, east of Naxtenxum.

Nachoj B: Three mounds on top of a hill, East of Naxtenxum.

Mukana: Four mounds around a patio, on top of a hill, southeast of Chilón. Tombs. Late Classic.

Chi Ko Tan: Site(?).

Chilón: A single platform.

Xicotanil: Undescribed site, east of Chilón.

Bolonkín: West of Chilón. A deeply looted site on top of a hill, with at least two mounds.

According to Andrieu (pers. com., 2010; Andrieu et al., 2011), on top of one mound, lied a sandstone stela. In a vaulted room underneath, the stuccoed walls were covered with Classic paintings, the date of which still remains unsure. Five panels at least have been registered and reported by the Mayan Esteem Project (Report 2001, vol. 3, num. 1; Domínguez, 2004). Late Classic to Postclassic.

Sheseña and Lee (2004) reported the existence in a private collection of three yokes that would have a Bolonkín provenance. One of them bore glyphic incrustations that they tried to decipher. One glyph could refer to K’el Ne Hix, an aj k’uh huun from Toniná, who assisted K’inich B’aaknal Chaak in the raid in 711 against Palenque that culminated in K’an Joy Chitam's capture. They consider that it proves Toniná’s control of the Chilón area. Those data would confirm indeed Toniná’s presence, but there remain doubts about the yokes provenance and authenticity, and the translation. The inclusion of the Chilón area in the Toniná’s political entity thus remains a probability.

The Tumbala-Tila ZoneTila (TLA) lies in a mountainous area northwest of Chilón. It is generally included in the Usumacinta Sub-Region, and most authors assert its inclusion in the Palenque political sphere, in spite of its localization on the left bank of Río Tulija. As a matter of fact, from Tila, a direct route opens toward Palenque.

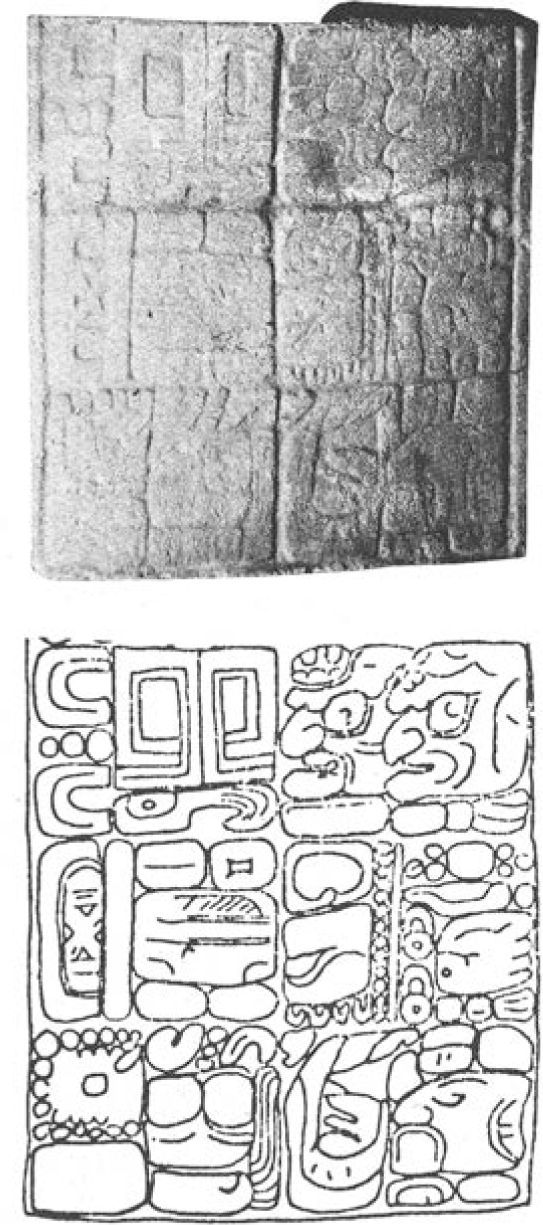

Tila is especially important for its three stelae, with calendar dates ranging from A.D. 685 to A.D. 830, registered respectively by Blom, Beyer and Morley (Mayer, 1984, 1991; Riese, 1981). Recent researches (C. Heck, K Bassie-Sweet et al., in prep.) offered a provenance from Ujaltón (Mayer, pers. com., 2011).

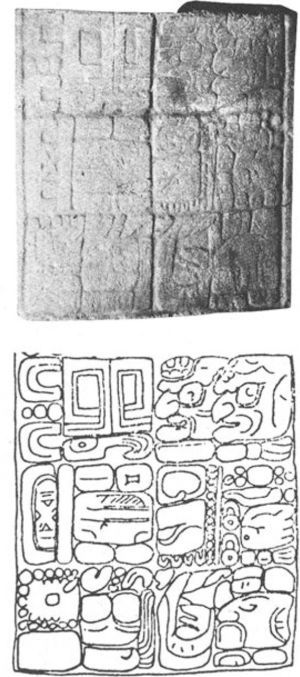

Monument 1 (former Stela A) is rather a limestone statue representing a standing dignitary. The remaining fragment looks very much like many Toniná monuments. Despite the absence of part of the inscription, the Long Count date on its back is probably 10.0.0.0.0 7 Ajaw 18 Sip (A. D. 840) (Bassie-Sweet et al., in prep.). H: 64 cm (figure 2).

Monument 2 (former Stela B) was found broken in two fragments, on top of a hill called Cruztiun, 8km east of Tila. A local informant confirmed that Cruztiun is another name for Ujaltón (Christian Heck, pers. com. to Bassie-Sweet, 2011). According to Mayer, it would rather be a limestone panel, 150 cm high, with a 15 glyphs inscription, which records the 9.12.13. 0. 0. 10 Ajaw (A.D. 685) date.

Morley later registered Monument 3 (Stela C), but its exact provenance remained uncertain, until Bassie-Sweet (et al., in prep.), confirmed an Ujaltón origin. It is presently in Bachajón and bears the date 9.13.0.0.0. 8 Ajaw 8 Woh (A.D. 692). H: 123 cm.

No related site had been reported or registered, even if Blom and Beyer forwarded such names as Chulum, Cruz Tun or Ujaltón. According to Bassie-Sweet (et al., in prep.), Cruz Tun is another name for Ujaltón.

Ujaltón: Blom registered a possible site. Recent researches by Heck and Bassie-Sweet confirmed that the Tila stelae “definitely stem from the site of Ujaltón. They were once on this site” (Mayer, pers. com., 2011, Bassie-Sweet et al., in prep.). “The Classic Period community of Ujaltón was situated at the bottom of the Tila valley near Petalcingo. Ujaltón was well placed to control not only the route to the east over the Tumbalá mountain, but also the route to the west along the Río Sabanilla to the Tabasco coastal plain. The amber deposits of Simojovel are just thirty kilometres to the southwest”. “These monuments indicate that there was a Late Classic Period elite population residing in the valley from at least A.D. 685 to A.D. 840” (Bassie-Sweet et al., in prep.).

Chulum: Extent ruins, according to Blom.

Jolja cave (Joloniel): Is located near Tila. Six groups of paintings with numerous glyphs as well as individuals have been registered in the cave. It is unnecessary here to dwell upon their decipherments (Bassie-Sweet, Pérez de Lara y Zender, 2000;; Bassie-Sweet et al., in prep.; Halperin, 2001; Laughlin and Bassie-Sweet, 2001; Sheseña, 2002; Zender, 2000; Zender et al., 2001).

Most readings coincide upon a long lasting and repeated occupation of the cave, from the Early to the Late Classic. Only Group 6 readings are pertinent for our purpose. It is composed of 16 glyphs in two columns with a red band painted down the centre. “Of interest in the Group C (6) text is the unusual placement of the calendar round date. The Tzolkín day name of 9 Akbal appears at A1 while the month position of 11 Kankín is at B2 (9.2.1.12.3 A. D. 477) (Stuart, pers. com. 1999) also noted that a place name found in this text occurs at the cave site of Yaleltsemen” (Zender, 2000). The place name that Stuart identified would correspond to the Sib’ikté Emblem Glyph, thus establishing a link with Yaleltsemen Cave and the Bachajón region.

The Sib’ikté entityToniná Monument 172, a carved limestone panel that depicts two ballplayers, mentions Sib’ikté as a Toniná related site (Skidmore, 2004). The figure on the left is identified by adjacent glyphs as K’inich B’aaknal Chaak, the best-known king of ancient Toniná. The name of the second ballplayer closely resembles that of Ruler 2, B’aaknal Chaak's predecessor as king of Toniná. The inscription ends with the Toniná emblem glyph, followed by another glyph that evidently refers to the Sib’ikté polity. The proposed 727 A.D. date for the monument would be just one month shy of exactly two k’atuns after the accession of B’aaknal Chaak. This is consistent with the numerous military successes, which he packed into his years of rulership.

These cumulated clues suggest that Sib’ikté would belong to the Toniná polity, or at least be a close ally. It would also suggest that Toniná would directly, or with Sib’ikté’s help, extend its influence until the Tila area, and therefore control in some way the Chilón region. Whether Tila pertained to the Palenque polity, stood midway between Palenque and Toniná or was under Toniná control remains to be ascertained, but it suggests that Toniná sought to exert its influence over Tila, thus getting an access towards Palenque, and above all the fertile plains of Tabasco. It is worth mentioning here, that in his study of the intricate exchange system of Postclassic and Colonial Chiapas, Navarrete (1973: 63) describes the road to Tabasco that the alcalde mayor from Tuxtla followed in 1783. After arriving at Ciudad Real (San Cristóbal de Las Casas), he successively crossed Huixtán, Oxchuc, Guaquitepec, Sitala, Chilón, Yajalón, Tumbala, before arriving at Palenque. It is more or less the same road that followed the Bishop Vargas y Ribera. Navarrete adds later that Tila was an important pilgrimage center for people living in Tabasco. While this author calls for caution in the identification of colonial roads with prehispanic routes, this Colonial period road linked the Ocosingo valley and the upper Jataté, with the San Cristobal (Jovel) Valley to the west and with the Tila area to the northwest, as a doorstep to the rich Tabasco coastal region.

It is interesting to remark, here, that while no prominent site has been registered in the Tulijá Valley, according to Bassie-Sweet (et al. in prep.), “the Classic Period site of Cutiepa, located in a small valley that runs parallel to the Tulijá basin, stands some 15 kilometres down the mountain side to the east of Tumbalá, and it has an eroded altar and a stela that is in the round style that is most commonly found at Toniná”. It could indeed be under Toniná’s influence, even if, as Baudez (1999) remarked, Toniná style monuments do not prove direct control by the polity. Two important prehispanic sites (Miraflores and El Retiro) are found along the Agua Blanca-Salto de Agua route. Their architecture as well as monuments is clearly related to the Palenque polity (Bassie-Sweet et al., in prep.). But Bassie-Sweet adds that on top of the second peak of Don Juan Mountain, there is a Late Classic site called Ha K’inna. The main temple layout is similar to the Palenque Cross Group buildings, but the site was also likely used as an outlook station for the defence of Palenque because it provides an almost 360° view of the surrounding territory. The presence of such a defensive site confirms indirectly that the Tila-Tumbala area was involved in the conflicts between Palenque and Toniná.

The southeastern bordersThe definition of the south-eastern limits of the Toniná polity is much more complex. The relative lack of survey and excavated sites impedes their proper identification. Besides, as Mayer notes (2007a and b), several monuments of Toniná characteristic style, but of unknown provenance, have been registered. Both Santo Ton monuments, a pedestal and a dignitary statue, obviously belong to the Toniná-style corpus (figures 3 and 4). A small site with three or four structures was registered in Santo Ton (Blom and Duby, 1955-7; Palacios, 1928). Besides the Santo Ton monuments, others monuments such as the Lacandon Altar ––former Thompson T47–– (Becquelin and Baudez, 1979-82) could come from any unknown site. This sandstone disk bears the date 9.13.15.0.0. (A.D. 706). The advanced deterioration of its surface does not permit the identification of a central Ahau, as in other Toniná disks. Given the monument size and weight, it would be surprising if it had been moved a long distance from the Ocosingo valley. It probably comes from Toniná or another nearby site. Mayer (2007b) mentions the presence of an unprovenanced pedestal in the same collection, and published a photo (1984, pl. 187).

Further towards the Usumacinta area, at least one mound and two plain circular altars have been reported on the small site of Huaca, but it is impossible to ascertain more than its existence (Blom y Duby, 1955-57). During her visits to Xoc, Ekholm-Miller (1973) registered several small Late Classic settlements. The Xoc site itself, which is located near the Rio Jataté, includes several platforms, a pyramidal mound and a small ballcourt. Given its location along the Jataté route towards the Usumacinta region where Toniná conducted several expeditions, the Xoc region could obviously be, at least partially, under Toniná control.

According to Mathews (1983), the Toniná polity extended till the limits of the Bonampak polity, and Bonampak suffered from Toniná aggressive expansion (Martin and Grube, 2000). The recently discovered site of Plan de Ayutla, with its huge ballcourt and its important structures, may represent an intermediate polity (Anaya Hernández, Guenter and Zender, 2003). The lack of monuments at Plan de Ayala does not allow its final identification as Sak Tz’i, but available data from other sites strongly suggest that Plan de Ayutla was closely related with Bonampak, and that it stood as an obstacle to Toniná’s expansion towards the Usumacinta (Bíró, 2004). At least, we can ascertain that Sak Tz’i figured among Toniná’s adversaries. Whether Plan de Ayutla did form an independent polity or was under Bonampak political control, its existence contributes to a substantial reduction of Toniná territory. Indirectly, its existence reinforces the possibility that the Xoc area was under Toniná’s control.

To the south, as already mentioned, the Toniná polity as proposed by Mathews includes the Santa Elena Poco Uinic site, but its limits fall midway between Toniná and Chinkultic and the Comitán basin. There is little doubt that Tenam Puente, Tenam Rosario or Chinkultic did not belong to the Toniná polity. In spite of the absence of dates and of an Emblem Glyph, and even taking into account the two Sacchaná stelae and the La Esperanza disk, the style of the Chinkultic monuments differs markedly from those of Toniná. We can surmise that Chinkultic formed an independent polity. The same would be true for Tenam Rosario (De Montmollin, 1989). Tenam Puente counts with two stelae and several monuments that bear a general resemblance with the Toniná ballcourt tenoned captives (Laló Jacinto and Aguilar, 1993). This is quite insufficient to consider seriously an influence from Toniná. Such similarities are not truly significant since, as Baudez noted (1999), several sculptural characteristics of Toniná (such as in the round statues, captives or pedestals) can be found at other sites: Tenam Puente itself (st. 2), but also Chuctiepa (statue) and Tortuguero (st. 3), that undoubtedly belonged to the Palenque polity. Lastly, recent researches in the Las Margaritas area permitted the identification of some 25 Late Classic sites, such as M II 28, Najlem and M II 34 (Álvarez, 1993; Álvarez, Lowe and Pérez Suárez, 1996). According to Álvarez, those sites rather show similarities with Chinkultic. It is still impossible to define precise polities for the Comitán area, but there is no doubt that they are completely outside any Toniná influence or control. The last site to be considered here is Santa Elena Poco Unic.

Few people have visited Santa Elena Poco Uinic (Mathews, 2009). It is located about half way between Toniná and Chinkultic, on a relatively flat area flanked on three sides by steep drop-offs. To the northeast, the land falls abruptly away, offering a view of the Tzaconejá and upper Jataté rivers. Santa Elena Poco Uinic contains numerous mounds and terraces, and according to Mathews, it rather shows similarities in stone masonry and style of monuments with Chinkultic and Tenam Puente. Mathews indicates that the site had stronger affiliations with those sites to the south and southwest rather than with Toniná to the northwest. A few other minor sites have been registered in the Soledad valley, such as Puerto Rico and El Amparo, where one monument is dated 9.11.0.0.0.

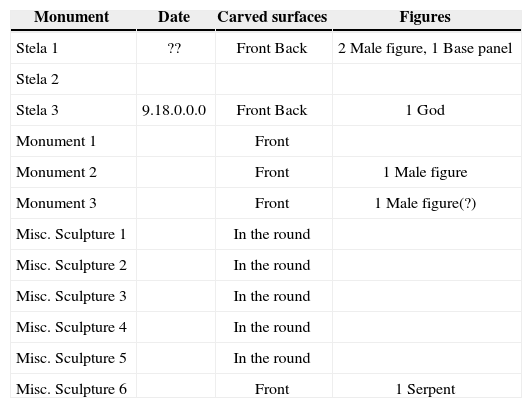

During his short visit in 1980, Mathews registered the 12 known monuments (Table 2). A weathered emblem glyph on Stela 3 indicates that Santa Elena Poco Uinic might have been the capital of a small kingdom late in the Classic Period. Stela 3 also mentions a possible local ruler, Yax B’alam (born A.D. 766(?), ruled A.D. 782-790). It implies a possible exclusion of the site from any Toniná influence. All the same, Mathews remarked that Misc. 2 and 3 and Misc. 4 and 5, respectively, have the form of “Statue Bases” or pedestals that are so common at Toniná: roughly square blocks of stone with a central hole for a tenoned sculpture. At Santa Elena Poco Uinic, these pedestals appear to be plain, apart from being dressed and perforated. Given its location, its Emblem Glyph, the presence of a local ruler and the existence of possible satellite sites (Puerto Rico, El Amparo), Santa Elena Poco Uinic probably did not pertain to the Toniná polity.

The Santa Elena Poco Uinic Monuments. Monuments 2 and 3 are possibly two halves of the same monument. Miscellaneous sculptures 4 and 5 are also possibly two halves of the same monument.

| Monument | Date | Carved surfaces | Figures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stela 1 | ?? | Front Back | 2 Male figure, 1 Base panel |

| Stela 2 | |||

| Stela 3 | 9.18.0.0.0 | Front Back | 1 God |

| Monument 1 | Front | ||

| Monument 2 | Front | 1 Male figure | |

| Monument 3 | Front | 1 Male figure(?) | |

| Misc. Sculpture 1 | In the round | ||

| Misc. Sculpture 2 | In the round | ||

| Misc. Sculpture 3 | In the round | ||

| Misc. Sculpture 4 | In the round | ||

| Misc. Sculpture 5 | In the round | ||

| Misc. Sculpture 6 | Front | 1 Serpent |

The current data thus suggest that the main body of the Toniná polity would extend from the vicinity of Xoc and the lower Jataté valley, to at least the still unidentified Sib’ikté site or entity, in the vicinity of Tila. Whether Tila was subject to Toniná authority or was disputed between Toniná and Palenque still remains unclear.

The Toniná territoryWhatever the case, the Toniná polity would mainly extend on a northwest-southeast axis (map 1), parallel with the mountainous area that lies to the northeast, and cover a much more reduced territory than proposed by Mathews (1983). The main incognita remains its western limits (Culbert, 1965; Paris, Taladoire and Lee Jr., in press). Epigraphic evidence currently suggests that most of Toniná political and military adversaries lie to the north and east (Martin and Grube, 2000). In A.D. 687, Toniná suffered a defeat at Palenque's hands, but afterwards won several battles against other adversaries, till its victory upon Palenque in A.D. 711. In A.D. 717, Toniná’s monuments claim military success against a site, which may be either Calakmul or, more likely, Tortuguero. During K’inich B’aaknal Chaak reign, Toniná conducted successful raids against La Mar and the undefined site of Anay Té. In A.D. 715, Toniná claimed victory against Bonampak, then in A.D. 786 against Bonampak again, as well as against the polities of Sak Tzi and Pomoy. Recent researches proposed that the Pomoy site could be located in southeastern Chiapas, on the fringes of the Usumacinta valley, in the same area (Bernal Romero y Laló Jacinto, 2006). Such battles repartition indirectly confirms the general disposition of the Toniná polity.

We are thus confronted with a significant reduction of the Toniná polity and with the relatively low estimates of the entity population. We may then wonder about Toniná ability to muster strong enough armies to win repeated victories upon its neighbours. As already mentioned about Palenque, its rivals did not probably dispose of many more warriors, but they were mostly fighting in their own territories, while the Toniná warriors conducted faraway raids and expeditions.

A possible explanation could lie in a somewhat different political organization of the Toniná entity (Taladoire, in press). In most neighbouring political entities, secondary centres are located at a mean distance of 20km from the main centre. Such is the case with Yaxchilán satellites of La Pasadita, El Chicozapote and Ojos de Agua, or with Piedras Negras satellite centres, El Cayo and La Mar (Golden and Scherer, 2013). In only a few instances are such distances shorter, as between Pomoná and Panhalé (8km) or Bonampak and Kuna (6km). In the Toniná polity, on the contrary, many secondary centres such as Mosil, Laltic and Petultón are located in the city vicinity, with a mean 7km distance. Even Santo Ton is only 14km away. In these secondary centres, we register the presence of monuments, ballcourts and small temples. A few secondary centres such as Guaquitepec or Ujaltón were located further away, about 35km. However, while in other polities most secondary centres occupy a peripheral position, several secondary centres in the Toniná polity are centrally located. This suggests that some important lineages, or maybe politically or military important groups, were allowed to live not in the centre proper, but rather in close-by sites.

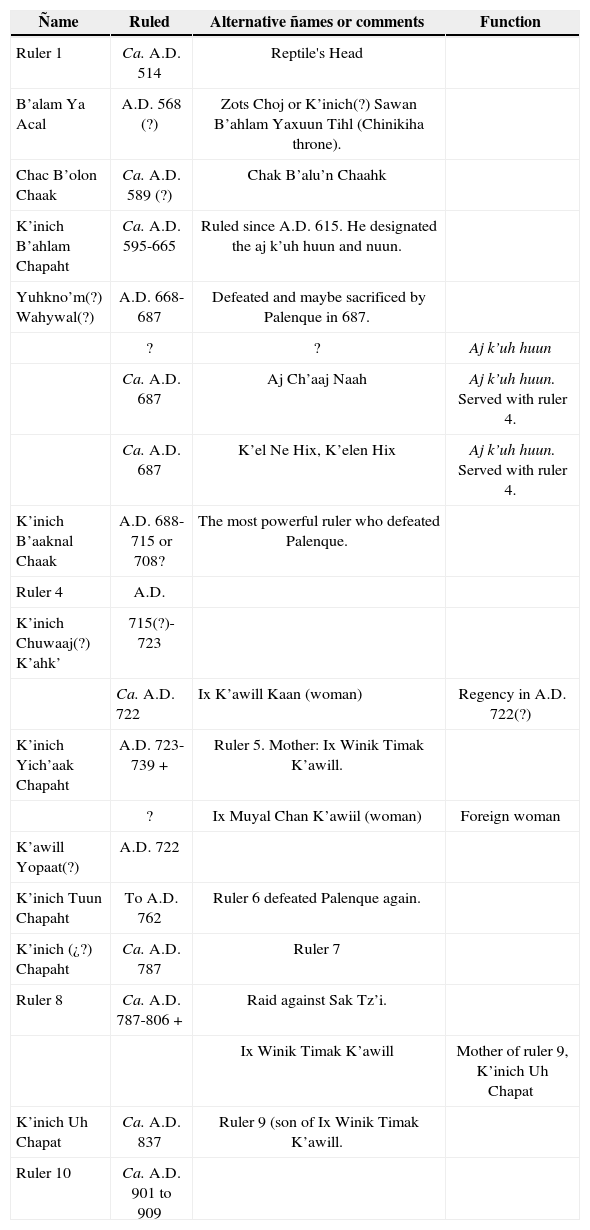

A distinct political structureThe epigraphic data provide a possible explanation for the highly centralized political structure of the Toniná polity (table 3). In A.D. 633, one of the first Toniná rulers, K’inich Hix Chapat, designated minor lords, Aj Ch’aaj Naah, K’el Ne Hix (or K’elen Hix) and a third unknown individual, as aj k’uhuun and nuun (M 154) (Martin and Grube, 2000: 179). Based on epigraphic evidence, these minor lords likely played important administrative and military roles, and potentially priestly or scribal roles as well, but their exact responsibilities remain poorly understood (Martin and Grube, id.), The aj k’uhuun were closely linked with the Toniná dynasty, since they served Ruler 2, and most of all K’inich B’aaknal Chaak, while at least one of them seems to have played an important part in the regency before Ruler 4's reign. If the Bolonkín yokes were authentic, one of these aj k’uhuun, K’el Ne Hix, would have participated in the victorious raid against Palenque. Sheseña and Lee (2004) assert that he played a leading role in the Bolonkín area.

The Toniná dynasty and related individuals.

| Ñame | Ruled | Alternative ñames or comments | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruler 1 | Ca. A.D. 514 | Reptile's Head | |

| B’alam Ya Acal | A.D. 568 (?) | Zots Choj or K’inich(?) Sawan B’ahlam Yaxuun Tihl (Chinikiha throne). | |

| Chac B’olon Chaak | Ca. A.D. 589 (?) | Chak B’alu’n Chaahk | |

| K’inich B’ahlam Chapaht | Ca. A.D. 595-665 | Ruled since A.D. 615. He designated the aj k’uh huun and nuun. | |

| Yuhkno’m(?) Wahywal(?) | A.D. 668-687 | Defeated and maybe sacrificed by Palenque in 687. | |

| ? | ? | Aj k’uh huun | |

| Ca. A.D. 687 | Aj Ch’aaj Naah | Aj k’uh huun. Served with ruler 4. | |

| Ca. A.D. 687 | K’el Ne Hix, K’elen Hix | Aj k’uh huun. Served with ruler 4. | |

| K’inich B’aaknal Chaak | A.D. 688-715 or 708? | The most powerful ruler who defeated Palenque. | |

| Ruler 4 | A.D. | ||

| K’inich Chuwaaj(?) K’ahk’ | 715(?)-723 | ||

| Ca. A.D. 722 | Ix K’awill Kaan (woman) | Regency in A.D. 722(?) | |

| K’inich Yich’aak Chapaht | A.D. 723-739 + | Ruler 5. Mother: Ix Winik Timak K’awill. | |

| ? | Ix Muyal Chan K’awiil (woman) | Foreign woman | |

| K’awill Yopaat(?) | A.D. 722 | ||

| K’inich Tuun Chapaht | To A.D. 762 | Ruler 6 defeated Palenque again. | |

| K’inich (¿?) Chapaht | Ca. A.D. 787 | Ruler 7 | |

| Ruler 8 | Ca. A.D. 787-806 + | Raid against Sak Tz’i. | |

| Ix Winik Timak K’awill | Mother of ruler 9, K’inich Uh Chapat | ||

| K’inich Uh Chapat | Ca. A.D. 837 | Ruler 9 (son of Ix Winik Timak K’awill. | |

| Ruler 10 | Ca. A.D. 901 to 909 |

However, the role of aj k’uhuun and nuun remains difficult to understand (Martin and Grube, 2000), relative to the sajales of secondary centers of Palenque (Xupa, Miraflores), Pomoná (Panhalé) or Piedras Negras (El Cayo, La Mar) (Schele, 1991; Bíró, 2014). One of the most significant maya “sub royal” offices was called sajal (glyphic sa-ja-la), which seems to refer in many cases to second-tier rulers who oversaw satellite communities, rather like provincial governors (Jackson and Stuart, 2001). Sajals were apparently rulers of secondary sites within the kingdoms of Yaxchilán, Piedras Negras and Palenque, among others (Golden and Scherer, 2013). The principal subsidiary site affiliated with Piedras Negras was El Cayo, which was governed by several sajals who were all seated into their junior office within months of the inaugurations of the Piedras Negras kings, who “owned” them (Houston, 1993: 130). This contrasts with the long- lasting part of the Toniná nobles. Currently, no sajal title has been identified at Toniná.

Aj k’uhuun nobles played key roles in several kingdoms of the Late Classic period, and were probably more than modest “courtiers” (Jackson and Stuart, 2001: 224). These individuals frequently carry specific titles, such as the God C title that refers to rank and occupation within court society. This title never accompanies the personal names of supreme rulers or kings. Significantly, we know of no case in which a sajal bears the God C title, suggesting some exclusivity between these two subordinate terms (Jackson and Stuart, op. cit.). They were powerful lords in their own right, overseeing complex social units and evoking royal and cosmological symbolism in their sculpted monuments. Toniná M 110 cites two such holders of the God C title as witnesses of a period ending ritual by the king (Bíró, 2012). According to Lacadena (1996), a-k’u-Hun-na could mean “he of the divine books”. He even suggests that men and women could use this title. However, it remains uncertain whether the aj k’uhu’n were members of the royal family or members of other elite lineages. It also remains difficult to assert if they were ritual or military dignitaries, or both, even if, in the case of Toniná, one can surmise at least some warrior responsibility, as exemplified by K’el Ne Hix participation in the raid against Palenque.

Current evidence suggests that Toniná did not use kinship evidences like the rest of the Maya Lowlands (Ayala, 1995; Steward, 2009). One or two female references were found at the site, but not a single traditional male about has been recovered to date. Ayala (1995) remarks that the absence of patrilineal evidence is also documented among tzeltal communities, even if this is still a matter of debate. The kings of Toniná predominantly used the Capped Ajaw death statement to show genealogical connections between the different kings. This statement indicates the death of a parent and works as a traditional parentage statement. There are several instances where the Capped Ajaw death phrase is used at Toniná and one from the nearby site of Santo Ton. The earliest dated monument from Toniná that uses the Capped Ajaw death phrase is Monument 165 that refers to the death of the aj k’uhuun K’elen Hix. He oversaw the ascension of the two-year-old Ruler 4 in A.D. 706. This is followed by Toniná Monument 144, which records the death of Lady K’awiil Chan, in A.D. 722, a royal lady who used the Toniná Emblem glyph during the reign of Ruler 4. Following the pattern set by Palenque and Yaxchilán, she and the aj k’uhuun K’elen Hix were likely the parents of Ruler 4. Lady K’awiil Chan could be the daughter or sister of K’inich Baaknal Chaak, the ruler who died shortly before the ascension of Ruler 4. If K’inich Baaknal Chaak died without a legitimate heir, then her offspring would have a legitimate claim to the throne of Toniná. If we consider Ayala's proposal (1995) of an indirect dynastic succession at Toniná, these aj k’uhuun were of high enough rank to marry into the household of Toniná’s ruling family and to become the fathers of its kings.

Could such differences in political organization proceed from a distinct linguistic or ethnic background between Toniná and its lowland neighbours? According to Ayala (1997) and Wichman and Lacadena (2005), it is possible to identify linguistic peculiarities at Toniná. While the inscriptions belong globally to the Western Ch’olan tradition, a Tzeltalan substratum is registered at Toniná, as well as at Tila (Mon. 2), Joloniel, Yalaltsemen, Santa Elena Poco Uinic, Tenam Puente, Chinkultic and Sacchaná. These ethnic differences could explain Toniná’s hostility towards Chola’n entities, as well as its relative tolerance towards other highlands sites, that belonged to the same Tzeltalan substratum. Maybe because of the lack of documented epigraphic evidence, we do not have any evidence of warlike activities from Toniná towards any polity, either in the Comitán area or in the Central Chiapas Highlands, where Tzeltal and Tzotzil languages are spoken today (Ayala, 1997). On the contrary, we may even surmise that Toniná’s resistance to the collapse of other lowland Maya polities might be partially due to its economic connections with some Central Chiapas Highlands cities (Paris, Taladoire and Lee Jr., in press). As mentioned above, one route from this central Chiapas area, at least in Postclassic times, linked the San Cristóbal basin with the upper Jataté and the Ocosingo valley (Navarrete, 1973).

It remains difficult to define a Terminal Classic phase at Toniná. While the city suffered, after 909, a destructive raid from still unidentified aggressors, several data suggest that the valley inhabitants tried to restore its power as exemplified by the edification of new structures on the acropolis (Str. F5-2, in Becquelin and Taladoire, 1990: 1548-1551). Yadeun (2008) mentioned other examples of architectural activity in Toniná proper, during the Terminal Classic. Lastly, the settlement pattern in the valley demonstrated that, contrary to many sites, an important population remained in the vicinity of Toniná, even if most important sites are then located on the right bank of the Jataté, rather than on the outskirts of Toniná (Taladoire, 2008). Obviously, the hiatus at Toniná did not last long, and may have been shorter than we thought (Becquelin and Taladoire, op. cit.).

In their excellent study of the evolution of the Yaxchilán and Piedras Negras polities, Golden and Scherer (2013) develop a hypothesis on the importance of trust and territoriality in the growth and collapse of both entities. To summarize their model, both cities’ growth lies in the establishment of bonds between the ruling elite and the sajals residing in peripheral centres, such as El Cayo or La Mar. These peripheral centres played an active part in the defence of both polities, and grew accordingly. But their very growth contributed to their relative autonomy from the ruling city, thus slowly undermining its power. When Piedras Negras and Yaxchilán suffered severe defeats, the collapse of those secondary centres followed quickly. According to Golden and Scherer, both polities’ growth contains the very causes of their fall, through the fragility of their political structure.

The administrative and territorial structure of the Toniná polity differs in several respects from its neighbouring polities. Differences in its socio-political hierarchy, including the absence of sajals and a more important part played by the aj k’uhu’n, even in distant sites such as Sib’ikté, may be related to potential ethnic differences with neighbouring polities, and to a potentially more centralized administrative structure. Such differences may be related with the distinct location of secondary centres in the immediate periphery of Toniná, although further data is needed to confirm this hypothesis. A systematic study of available inscriptions at Toniná proper and on the other sites of its polity might shed some light on this issue. Bíró (2012: 84-85), who stresses the predominance of such titles in the western Maya region, thus contrasts the aj k’uhu’n of Toniná, with the sajals of Piedras Negras and Yaxchilán polities, even if he does not insist on possible different functions.

However, if, as we think, the Toniná rulers could rely on a faithful, trustworthy in Golden and Scherer's words (2013), intermediate class of secondary elites, who could potentially marry into the royal family, this could result in a tighter control of their population and territory. The sajals of other polities could effectively switch their allegiance to other cities, while the aj k’uhu’n involvement in the dynastic history of Toniná strengthened their connections to the ruling family. The physical proximity of their residences to the capital proper would have provided Toniná, in spite of its relatively reduced population, with the means to develop its aggressive and often victorious policy (Becquelin y Taladoire, 1990: figuras 3 y 4).

ConclusionIn many respects, most of all its resilience to the collapse in contradiction with most of its neighbours, Toniná stands apart from other Maya polities. In spite of its relatively reduced population, this city developed an aggressive attitude and obtained numerous victories, in the course of its history. The Ocosingo valley inhabitants even tried for some time to recover from the city destruction, after 909 A.D. In this essay, we argue that such differences might stem from a distinct political organization, based on a different political control of its territory, and on the importance of a Tzeltalan substratum that allowed the valley inhabitants to maintain alliances with their highland neighbours.