This study treats the social and specifically urban context of late humanism in eighteenth-century Mexico City and New Spain. Through the careful reconstruction of the lives of particular scholars, it argues that the specific configuration of urban space (including colleges, libraries, print shops and personal dwellings) should be taken into account when understanding important monuments in the cultural history of Mexico, like the Bibliotheca Mexicana of Juan José de Eguiara y Eguren. This distinct urban culture, in turn, was influenced by larger patterns of circulation in books, ideas and people that gave the late humanist culture of Mexico City both an internal coherence and made it an integral part of a larger cultural sphere.

El estudio aborda la vida social y urbana de los llamados «letrados» del siglo xviii en la Ciudad de México y la Nueva España. A través de distintos casos específicos se observará el papel de la configuración del espacio urbano (inclusos colegios, bibliotecas, talleres de imprenta y redes sociales urbanas) que permiten un entendimiento más profundo de monumentos importantes de la historia cultural de México, como la Bibliotheca Mexicana de Juan José de Eguiara y Eguren. Esta original cultura urbana cayó bajo la influencia de redes de circulación más grandes que incluyeron libros, ideas y personas, que dieron a la cultura humanística de la capital virreinal tanto una coherencia interna como una posición en un ámbito cultural más amplio.

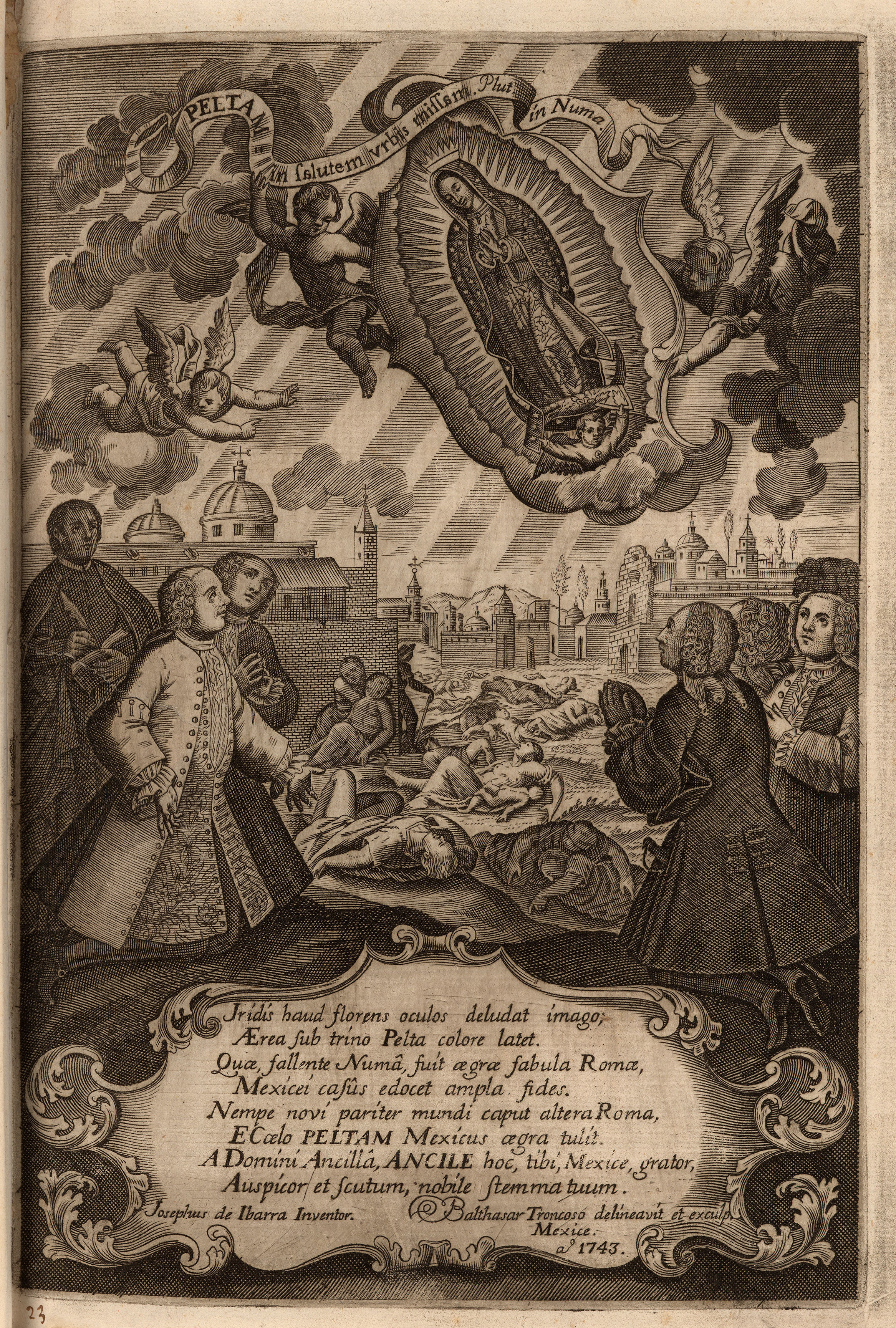

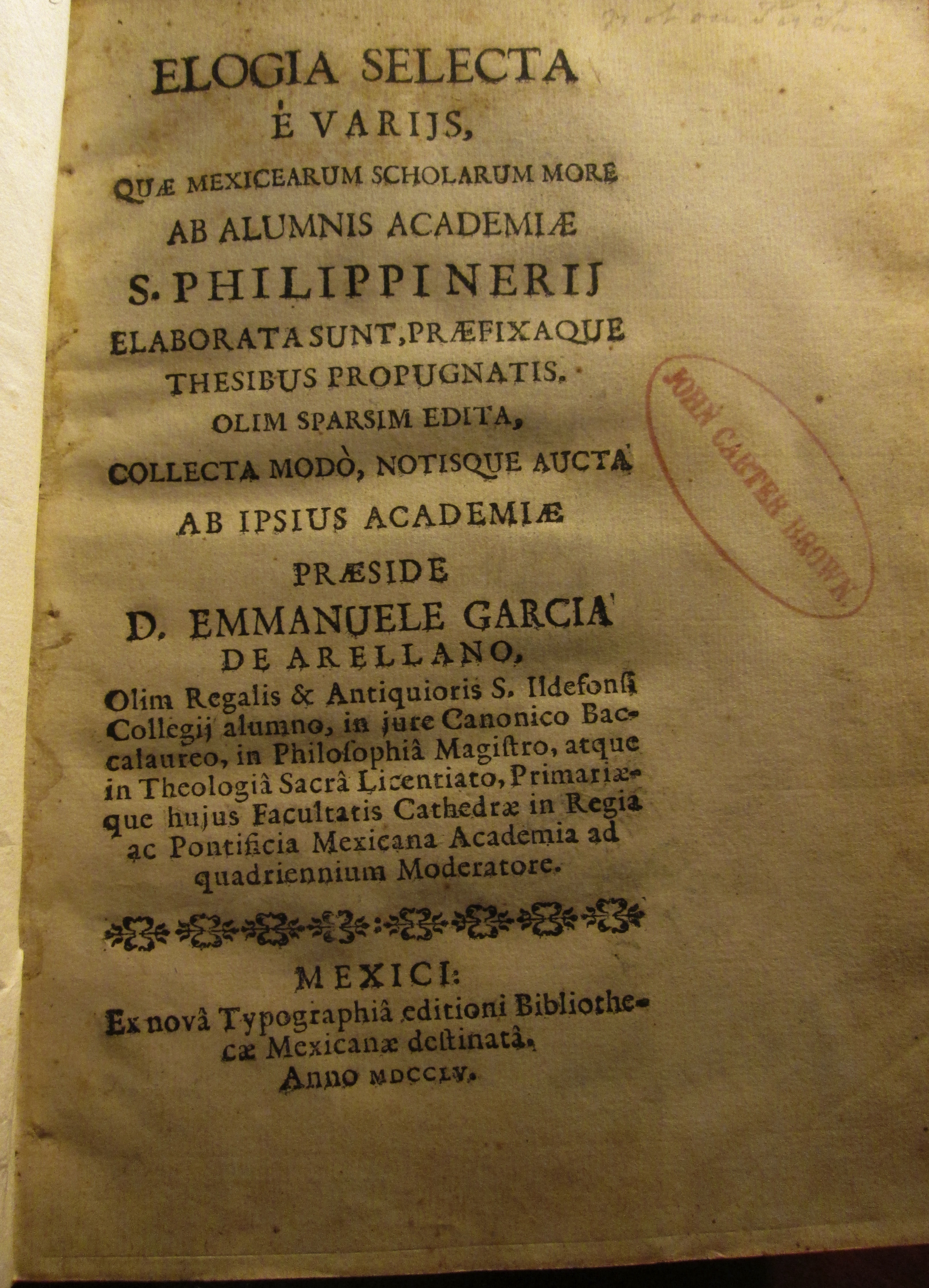

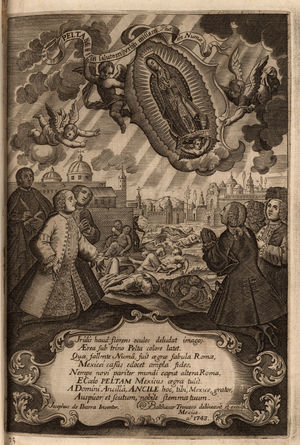

In the frontispiece of Escudo de armas de México (1746) of Cayetano de Cabrera y Quintero (1698–1775), angelic putti emerge from a break in the clouds carrying the venerated image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, which brings relief to the inhabitants of Mexico City in the midst of the matlazahuatl epidemic.1 In this engraving by Baltasar Troncoso y Sotomayor (1725–1791) (Fig. 1) after a sketch by the morisco artist of Spanish and mulatto descent, José de Ibarra (1685–1756), the Guadalupe floats above an idealized cityscape that recalls (but does not represent) both the center of Mexico City and the suburb of Tepeyac, where this Mexican Madonna is said to have appeared to the indio Juan Diego in 1531.2

The domes on the left evoke both the city's monumental cathedral and the future “collegiate” church of our Lady of Guadalupe, while the brick façade of the church on the right appears to be made of tezontle, a local volcanic rock used in the construction of a number of churches and convents throughout Mexico City.3 The mountains in the background, in turn, are reminiscent of the hill of Tepeyac or the mountains that surrounded the Valley of Mexico. Flanked by these impressive natural features and man-made structures, a typical depiction of plague victims occupies the middle ground. In the center of the scene lies a bare-breasted women cradling a child who lies face down on the ground, while a half-obscured figure with a hat and walking stick leans on a wall.4 Although they represent victims of all ages and both genders, in these highly classicizing figures of plague victims Troncoso does not hint that those of indigenous decent were the most affected by this deadly outbreak of typhus. Perhaps the artist agreed with Cabrera that the indios had been justly struck down for their excessive consumption of pulque, a pre-Columbian alcoholic drink made from the maguey plant that was closely associated with disorder and idolatry.5 In contrast to this scene of human misery, the foreground is occupied by the members of the city council (cabildo secular). These were the well-dressed gentlemen who in May 1737 had sought the intercession of the Virgin of Guadalupe to combat the plague, and, after the remission of the pestilence, officially recognized her as the patron of Mexico City, subsequently paying for the printing of Cabrera's account of the events in an act of pious commemoration.

Yet, in studies of the frontispiece one figure is normally passed over quickly in favor of discussions of the rise of this most important of New World Marian devotions.6 On the left of the composition stands a cleric, who leaps out of Troncoso's engraving thanks to the diagonal crosshatching of his garments, which contrasts with the horizontal linear hatching of the building behind him. In his left hand, he holds a book in which he writes with a quill pen. This learned ecclesiastic whose attention is being directly engaged by both the leftmost putto and the implied gaze of the Virgin on Juan Diego's tilma is generally agreed to be Cabrera himself, the erudite secular priest, whose careful observations and interpretations of the epidemic are recorded in the pages of the printed volume.7 More generally, this representation of Cabrera, pen in hand, reminds the observer of his membership in the class of highly educated civil and ecclesiastical functionaries, dubbed letrados by Ángel Rama, who inhabited and defined what the Uruguayan critic called the “lettered city” (ciudad letrada).8 This was a class of intimidating and solitary masters of Latinate learning, “bearded and grave,” as John Chasteen put it in the introduction to his translation of Rama's Marxian account of the relationship between erudition, caste and empire. Cabrera was thus one of an elite group of “clerics, administrators, teachers, professionals, writers and many public servants, all those who wielded the pen and were closely associated with the function of power.”9 As such, the frontispiece is also a vision of a highly hierarchical, Christian urban society blessed by the intercession of its own local Marian apparition and overseen by a class of letrados, both clerical and lay, whose richly patterned garments point to the wealth of New Spain's flourishing highland metropolis.

This said, we cannot escape the fact that this fresh-faced and clean-shaven Cabrera differs significantly from the image of the letrado presented by Rama and much cultural history of Viceregal Latin America. Not only is Cabrera neither “bearded” nor “grave,” but he is also not the disembodied author of a learned text who inhabits an urban space that exists as a mere idea in the head of the Spanish administrator who ordered the city's construction according to the abstract schema set forth in the leyes de Indias. Instead, he dwells in an idealized but specific urban environment, where he mixes with other segments of the population, both elite and non-elite, Spanish and non-Spanish. In short, he reminds us that the letrados not only had a cultural and intellectual history, but a social and specifically urban history too.

Equally underplayed is the fact that the Mexico City of the letrados was also an urban space imagined as a calque of Ancient Rome.10 As the passage from the Latin translation of Plutarch's Life of Numa carried by one of the putti makes clear (“a shield was sent for the salvation of the city”), the tilma of Juan Diego was akin to the shield (π¿λτη) that fell from the sky in Rome in the age of Numa Pompilius, which, once the site of its appearance had been consecrated to the Muses, caused the pestilence to abate.11 Similarly, Cabrera's verses at the foot of the engraving point to a Neo-Roman vision of New Spain's leading city: May your eyes not be deceived by this blossoming likeness of a rainbow; A bronze shield hides beneath its triple colors. This was the legend of the plague in Rome, which Numa tried to lessen. The great faith of the Mexican case teaches us the same lesson. Indeed, plague-ridden Mexico City, the capital of the New World, And the second Rome likewise received a shield from heaven. I congratulate you, Mexico City, on your shield from the servant of the Lord, And I auspiciously begin my account of this, your noble escutcheon.12

If, as Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra has argued, the mental world of creole scholars remains to be fully explored, their social and urban context and its dialectical relationship with the ancient Mediterranean urbs have been left almost completely unexamined.13 This is particularly true for Anglophone scholarship, which is still in the shadow of David Brading's high intellectual histories of Viceregal political thought.14 Hispanophone scholarship is, of course, much richer. Mexican scholars of New Spain have undertaken extraordinarily detailed studies of the biographies and textual production of Cabrera and his learned contemporaries.15 The archives of universities and colleges have been mined for details about institutional life.16 We now know more than ever about the social networks of itinerant European scholars, like the antiquarian and devotee of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Lorenzo Boturini Benaducci (1702–1753), whose animosity toward Cabrera – a sign that learned sociability did not necessarily have to involve friendship in the conventional sense – has recently attracted attention.17

Great strides have also been made in the bibliographical and philological study of New Spain's rich culture of post-Renaissance classicizing scholarly practices, collectively known as “late humanism.” As several generations of Mexican cultural historians have underlined, the humanist movement had a long history in New Spain beginning in the mid-sixteenth century with a translatio studii of scholars from the Iberian Peninsula, such as Francisco Cervantes de Salazar and Bernardo de Balbuena, who built the foundations of a self-reproducing culture of humanist learning that would develop in parallel and symbiotic ways with the European and Iberian Asian strands of this global tradition. While some in the twentieth century saw the roots of modern atheism in the movement, it is now almost universally acknowledged that for most letrados there was no inherent conflict between their commitments to humanist learning and Christianity, even in its most baroque incarnations. For instance, the theologian, humanist and bibliographer, Juan José de Eguiara y Eguren (1696–1763) was both an avid reader of Cicero and frequently engaged in mortification of the flesh, including abstinence, regular self-flagellation and the wearing of a spiked chain on his arm and leg.18 Indeed, to underline this union of seemingly incongruent elements, the tradition is often referred to as “Christian humanism.”19

Despite the deep and lasting intellectual changes that took place during the reigns of the last Habsburgs and first Bourbons, this movement (by this stage normally called “late humanism” in Anglophone scholarship) remained coherent and vibrant in the first decades of the eighteenth century. Indeed, we must not forget that Mexican scholars of Novohispanic humanismo were among the first to recognize the considerable cultural continuity over the Baroque-Enlightenment divide alongside the German scholars who in the 1930s coined the term “late humanism” (Späthumanismus) popularized more recently by Anthony Grafton.20 As these early-twentieth-century Mexican scholars taught us, this later stage of humanism, like its earlier incarnations, was characterized by deep engagement with classical and earlier humanist texts in Latin and the vernacular, and the application of their insights in texts framed in similarly classicizing Castilian and Neo-Latin genres, including epistles, dialogs, orations and epic poems.21

This said, we still lack more holistic reconstructions of Viceregal Latin America's local, and in particular urban, cultures of learning, and the rich veins of Christian humanism that dressed Mexico City in classical garb.22 It is only in this way that we can begin to ask questions about how humanist culture was produced, consumed and spread within the city, the Viceroyalty and globally. As I argue below, there is a hitherto under-appreciated social and particularly urban dimension to the high cultural history of Viceregal Latin America. Urban intellectual life was supported by clusters of institutions and scholars that remade their cities in the image of the archetypal urban context, Rome, with lesser but not unimportant roles for Athens and Jerusalem as well. By concentrating on the learned circle of Cabrera, which included important figures, like Eguiara and the Jesuit late-humanist Vicente López (1691–1757), I reconstruct the role of local friendships and inter-urban interactions in the production and spread of late humanist knowledge, and the significance of a largely unknown learned academy, the academia eguiarense.23 This “Rome of the New World” was of course not hermetically sealed, but was also a porous urban space where learned lives played out within the context of larger patterns of circulation in books, ideas and peoples of many castes and complexions. By moving across scales from a single room to the transatlantic network, I make the case for reaching for both the microscope and the telescope when trying to understand Novohispanic late humanism.

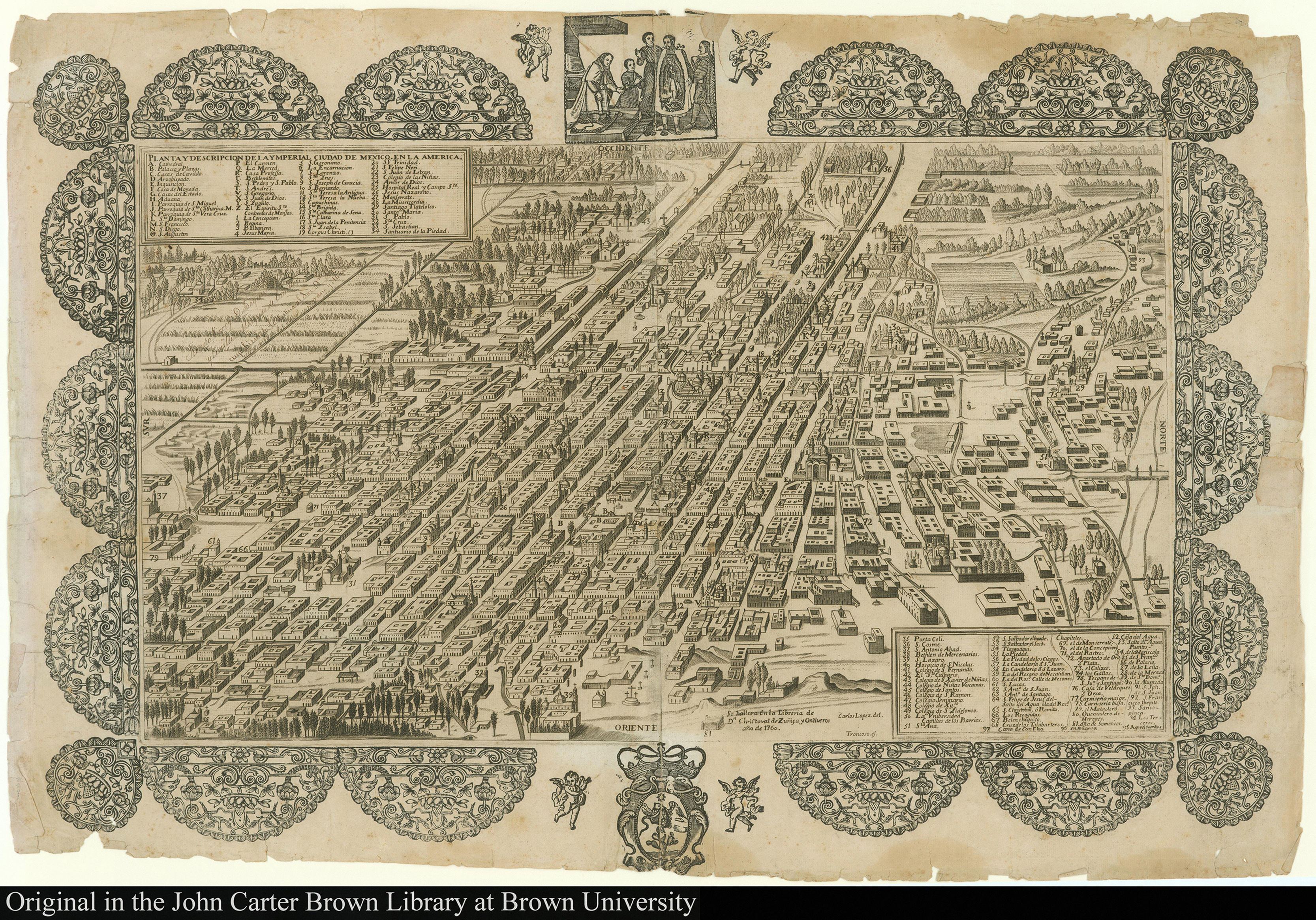

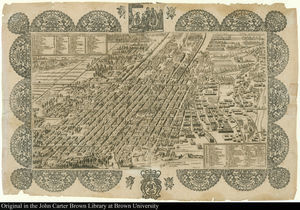

The social life of late-humanist learning in Mexico CityJuan José de Eguiara y Eguren and Vicente López were firm friends. This close relationship partly reflected their shared ties to the Society of Jesus and its densely-packed groupings of colleges in the urbanized areas of New Spain, which we begin to appreciate if we examine a roughly contemporary map of Mexico City, entitled Planta y descripción de la ymperial ciudad de México en la América (1760) (Fig. 2). For instance, Eguiara had studied grammar, classical authors, philosophy and basic theology – collectively known as the “arts” – at the colegio máximo de San Pedro y Pablo (marked “S”). In this venerable building that had suffered from predictable subsidence (the college's church had sunk so far beneath street level that it had to be reached by a staircase!), Eguiara progressed through the educational program codified in the Ratio studiorum (1599), each stage of which had a dedicated room in one of the college's two grand patios with the aula mayor providing a space for the delivery of declamations in Latin and the vernacular.24 While officially taking classes at the colegio máximo, Eguiara resided in the nearby colegio de San Ildefonso (marked “49”), where students lived and studied under the watchful eyes of learned Jesuits, performing repetitions and making use of the college's large library.25 While López's education is much less well documented than that of Eguiara, this native of Andalucía had a similar, if somewhat less privileged experience to his learned contemporary, imbibing Jesuit Christian humanism during his novitiate at the famous Jesuit college at Tepotzotlán and while studying arts at Jesuit colleges in nearby Puebla. Alongside Mexico City, this was an important educational center from the mid seventeenth century onwards that provided many of the educated clerics and laymen who staffed institutions in the Viceregal capital, where López and Eguiara would go on to meet.26

This training in grammar, classical authors, philosophy and basic theology was considered an essential preliminary step toward higher degrees, such as theology, a doctorate in which Eguiara received in 1715, while also providing the foundational training for those, like both López and Eguiara, who showed a proclivity toward the humanistic arts and who would go on to engage in late humanist scholarship. More practically, for both López and Eguiara, it was this early training in Jesuit colleges that laid the groundwork for their later ascents through the cursus honorum of the university and ecclesiastical hierarchy. Eguiara's early success in humanist studies and later in theology was a prerequisite for the numerous academic and administrative positions in the University (marked “50”) and his career in the Church that culminated in his election as the Bishop of Yucatán in 1752. Prevented by his weak voice from becoming the preacher that his rhetorical talents deserved, López pursued a teaching career in the Jesuit Order, which equally necessitated a strong background in Christian humanism. This led to a teaching position at the college-seminary of San Gregorio (marked “V”), a Jesuit institution for poor students and indigenous elites, where he heard confessions at the weekly congregations of indios who traveled from several leagues around the college, and gave instruction in basic literacy to caciques in preparation for their future careers as heads of their pueblos and, increasingly in the course of the eighteenth century, as secular priests.27

Yet, beyond such careerist concerns, this shared curriculum also built the foundations of a common culture of Christian humanism that cemented the friendship between two men who pursued this aspect of Jesuit culture with particular gusto. Indeed, this common set of scholarly interests in Christian humanist culture permeated all the interactions between Eguiara and López for which there is surviving evidence. Throughout their Latin correspondence, now in fragmentary form in manuscripts in the National Library of Mexico, the two clerics cultivated a neo-classical style full of richly layered classical allusions. Eguiara and his “dear” (carissimus) friend López even modeled their friendship on classical antecedents. As López put it, he was the “Atticus” to Eguiara's “Cicero,” making their correspondence the mirror of Mediterranean Antiquity's most famous and polished epistolary exchange.28 Indeed, the parallels were considerable. Like Cicero, Eguiara was an orator, who delivered numerous sermons and orations in Latin and the vernacular on important occasions in their New World metropolis, which allowed him to climb the greasy pole of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, culminating in a bishop's miter, a dignity equal of any consulship. López, on the other hand, was a man of deep classical learning who shunned the limelight, although in his case this was more due to his ill health than any particular interest in Atticus’ Epicureanism.

As in Antiquity, Latin epistles were a conduit for expressing all sorts of thoughts and desires, and on occasions emotions could run high. Both Eguiara and López were avid readers of the Acta eruditorum, a Latin journal published in Leipzig that circulated from Mexico City to Moscow. Yet, a journal that catered to both Catholic and Protestant readers could hardly avoid controversy in a Republic of Letters that was still divided along confessional lines. When one of its contributors called Luther “divine” and “pure,” López was unable to contain his rage, and dashed off a scathing letter to his friend: What a heinous crime! What a monstrosity! What a lie unheard of to earlier ages! But do you need my opinion on these books? I’ll be brief. They are entirely pernicious, and no Podalirius, no Machaon… no Hippocrates could cure them of their disease.29

Not even the great healers of Antiquity could cure the malady of heresy, which although an ocean away could still cause rage in this Christian Rome in the New World, a space where both close friendships and deep hatreds coexisted.

Such controversies could also spur the two men to collaborate in shared late humanist projects with wider scholarly and societal significance. On one occasion in the late 1740s, despite suffering from unbearable toothache, Eguiara wrote to López to praise his friend's Latin hymns on the Virgin of Guadalupe.30 These Horatian odes were significant, Eguiara told him, as they disproved the judgment of Manuel Martí, the leading Spanish humanist of the day, that the Americas in general – and their own highland metropolis in particular – lacked all the trappings of learned culture. In the light of the achievements of López and others, he declared, no one should believe the libelous claims expressed in Martí’s widely acclaimed collected correspondence: To whom among the Indians will you turn in such a vast desert of letters? I won’t ask to which teacher will you go, from whom you might learn something, but will you find anyone at all to listen to you? I won’t ask whether you will find anyone who knows anything, but anyone who wants to know anything at all, or, put simply, anyone who does not despise letters. Indeed, which books will you leaf through and which libraries will you peruse…? So ponder this: what does it matter if you are in Rome or Mexico City, if you just want to haunt the avenues and street corners, to gaze at the magnificence of the buildings, to be idle, and to waste away while you schmooze with all and sundry like a slimy politician?31

López, Eguiara insisted in his epistle, was living proof that these comments were baseless. Meandering through Mexico City could be just as rewarding as walking the streets of Rome.

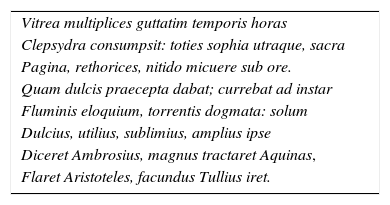

These accusations cut so deep, of course, as the Spanish antiquarian and these New World scholars were in many ways cut from the same cloth. Although Eguiara and López did not share Martí’s complete distain for the scholastic culture of the universities, they did attach considerable value to the brand of purist late humanist learning, sometimes called “Neo-Renaissance” humanism, that Martí had popularized.32 For them, as for Martí, it was a way to revive humane, and in some cases even sacred, letters in the Spanish and Novohispanic branches of the Republic of Letters that were widely considered to have fallen behind their French and British counterparts.33 Indeed, looking back on their shared youth in university circles in 1761, Andrés de Arce y Miranda, the bishop elect of Puerto Rico, remembered that Eguiara had stood out among his contemporaries for his rejection of the “slovenliness and barbarity of style with which the scholastics usually treat philosophical and theological topics,” preferring “pure and fine Latinity with very suitable shows of erudition, passages of shining eloquence, and transitions both charming and natural,” the essence of “Neo-Renaissance” late humanism.34 Even when giving lectures on theology at the University, Eguiara never failed to live up to the humanist ideal. As Cayetano de Cabrera y Quintero put it in his laudatory poem, Sapientiae sidus, for friend's election as Chair (de vísperas) of Theology in 1715:glittering speaker's water clock devours Many hours of time drop by drop As both branches of learning, the holy writ And rhetoric, spring forth from elegant lips. How the sweet mouth gave lessons; speech flowed like a river Spilling out dogma. Only Ambrose himself would have spoken more sweetly; Only the great Aquinas would have deliberated more suitably, Only Aristotle declaimed more loftily, only eloquent Tully professed more splendidly.35

As a result of their participation in the “Neo-Renaissance” movement within late humanism, the vitriolic responses to Martí by both Eguiara and López were couched in longstanding humanist genres written in an overtly Golden Age Latin style. In 1744, Eguiara set about compiling the famous Bibliotheca Mexicana, a Latin bio-bibliographical encyclopedia of every scholar born, educated or resident in New Spain from the Conquest to his own day, which aimed to crack the nut of Martí’s letter with a several-thousand-folio-page Latin hammer that mirrored both the overall arrangement and the polished prose of Martí’s edition of Nicolás Antonio's Bibliotheca Hispana Vetus. Similarly, López composed a classicizing dialog in the style of Cicero's philosophical works, entitled Aprilis dialogus, in which a Spaniard, Belgian and an Italian discussed the merits of Martí’s assessment of their city's cultural achievements in the shade of a plane tree (sub umbrosa platano) in the grounds of a villa near Mexico City.36 Drinking chocolate for inspiration, the interlocutors concluded that Eguiara's Bibliotheca Mexicana was a monument worthy of the high cultural standards of their home city (patria) and an ornament to the Republic of Letters (respublica eruditorum) as a whole.37 This was printed as a preface to the Bibliotheca Mexicana uniting the works of these two learned friends in the same cover. When we look at this important monument of Mexican cultural history, then, we should think, not of Eguiara the lone scholar, but of a life learning lived among friends.

Epistolary correspondence and learned networks in Mexico City and beyondUnlike many epistolary exchanges in the early modern world that - as the well-known case of the Jesuit polymath Athanaius Kircher (1602–1680) shows – spanned numerous continents and oceans, Eguiara and López's friendship and scholarly collaboration were nurtured by their extreme proximity.38 Their houses were separated by little more than a kilometer of urban streets: López lived in the Jesuit college of San Andrés (marked “T”), while Eguiara lived in the shadow of the Augustinian convent in the calle de San Agustín (marked “O”). Looking at the contemporary map, we can even imagine the route they might have taken to visit each other, a walk of only four blocks north and one block west through the heart of the city, passing important ecclesiastical building like the convent of the Capuchins (marked “13), the casa professa of the Jesuits (marked “R’) and the convento de Santa Clara (marked “16”). Indeed, this sort of proximity is an underappreciated category in much current cultural history that tends to foreground communication over large distances.

Such proximity not only allowed Eguiara and López to interact and correspond as they worked to show that Martí’s accusations were unfounded, but also to share ideas and books easily. For Eguiara, who in his Bibliotheca Mexicana sought to document every “Mexican” author and their works from the Conquest to his own day, López was a goldmine of knowledge on the voluminous writings of the Jesuits in New Spain. Eguiara did not waste this opportunity. We know, for example, that on one occasion Eguiara asked his friend to send him any and all Jesuit annual letters that were to hand in the library of the colegio de San Andrés.39 In composing their defenses of the learned community centered on Mexico City, both men also had urgent need for Nicolás Antonio's Bibliotheca Hispana Nova, the primary bio-bibliographical encyclopedia for the Hispanic world. Living so close to each other meant that they could share a single copy of this rare book, which made its way back and forth between them. All López had to do was to write to his friend “to send either your or my lad (puer) over with the book.” If this Mexican Mercury made haste, López could have had the book on his desk within half an hour.40

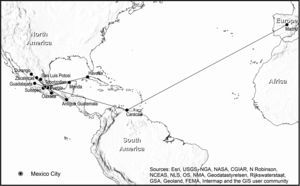

This is not to say, of course, that close-knit local networks of scholars in a single urban space represented the sole defining feature of Eguiara's intellectual world. As well as a learned social circle within walking distance, he also possessed a larger correspondence network that was just as important to the success of the Bibliotheca Mexicana project (Fig. 3).41 Between 1744 and 1745, Eguiara sent out a string of letters to his friends and former associates at the University, asking them to collect references to books and manuscripts produced in their provinces. This larger network linked Eguiara to Durango, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Guadalajara, Sultepec, Puebla, Merida, Oaxaca and Guatemala, as well as to Habana in the Caribbean and to Caracas in the newly-formed Viceroyalty of New Granada, which due to its continuing inclusion within the ecclesiastical administration of New Spain remained an integral part of Eguiara's scholarly world. Indeed, the extent of his epistolary network was the primary reason Eguiara gave for restricting his encyclopedia to the continental and Caribbean regions of New Spain, rather than including all of the Americas. As he told his readers, “I will pass over almost in silence these areas, with which we have very rarely or never have any correspondence (commercium).”42 Yet, just as Mexico City itself was not closed to the rest of New Spain, Eguiara's social network in the Americas was not hermetically sealed. In particular, it was, as one would expect, linked to Peninsular Spain thanks to the constant back and forth of administrators, immigrants, merchants and ecclesiastics across the Atlantic. In 1746, for instance, a letter arrived on Eguiara's desk from his former student, Antonio Pacheco y Tovar, the Conde de San Javier, who had studied theology under Eguiara in Mexico City. Pacheco had previously been based in Caracas, but had had to leave for Spain on urgent business, and penned his response from the other side of the Atlantic, offering to put Eguiara in touch with his friends in the Viceroyalty of New Granada who could provide more details of books and manuscripts held there.43

Eguiara's correspondence network described in Castro Morales (1961).

In some cases, we are lucky enough to have detailed accounts of who compiled and couriered the lists of books and manuscripts in Latin, Castilian and indigenous languages that were of such interest to Eguiara. Examining the chain that linked him to his correspondents, it becomes clear that the Bibliotheca Mexicana was not the product of one Novohispanic scholar and his individual distinguished correspondents, but of many individuals of different ranks spread out across the Viceroyalty. In late 1744, for example, Eguiara had written to a number of his friends and former students at the University of San Carlos in the Captaincy General of Guatemala. At a meeting of the university senate (claustro) called by the rector, it was decided that each religious order should elect a suitable member to compile a list of books and manuscripts produced in their province. Over the following year, the responses made their way to Mexico City. On August 5, 1745 the Provincial of the Franciscans, Fray Marcos de Linares, sent a list of Franciscan authors from the region compiled by Dr. Antonio Arochena, which on its way North passed through the hands of Captain Francisco Obregón in Oaxaca, and was carried to Mexico City by another Franciscan, Fray Francisco Antonio de Salazar. Writing back on November 20, 1745 Eguiara thanked Linares for his valued contribution to the “public good of our America” (bien público de nuestra America). Yet, the truth was that Linares was only partly responsible for this small scholarly triumph.44 Not only had he farmed out the actual intellectual work to a member of his local scholarly network, but the letter would never have arrived in Mexico City without social and infrastructural links that reached across the 1500 or so kilometers that separated the two cities. In short, in this intellectual world, there were few personal triumphs. Instead, intellectual life and projects like the Bibliotheca Mexicana were the product of multiple actors connected across a variety of distances.

Scholarship begins at homeAlongside urban and inter-urban social networks, another scale which has been largely ignored in studies of Eguiara and his contemporaries consists in the individual parts of the built environment, in particular private homes. Even when Eguiara was within his own four walls on the calle de San Agustín, he was far from disconnected from the wider world of late-humanist learning. In the first place, this is because these larger social networks frequently found their way into private spaces such as this. For instance, we know that Eguiara hosted social gatherings (tertulias) and dinners for his friends in his house, where erudite conversation about theology, philosophy and humanist learning were very much on the menu. At these events, books and works in manuscripts may even have passed around, since we know from his close friend for over forty years, Andrés de Arce y Miranda, that Eguiara was generous in sharing such unpublished material, including the texts of his Latin oposiciones (“job talks”). In the second place, the house itself was also something of a temple to learning. As Arce y Miranda noted, it was not decorated with paintings of his illustrious ancestors, despite the fact that being of noble Basque descent meant Eguiara had plenty to choose from, including members of the military orders of Santiago and Alcántara. Rather, it was adorned with images of “famous heroes of history” and “men illustrious in sanctity and learning,” a suitable setting for symposia that brought together the great and the good of Mexico City's intelligentsia.45

Not only did Eguiara live, sleep, socialize and study under the watchful eyes of exemplary scholars and historical figures, but he was also surrounded by the voices of Augustine, Cicero and Jerome that emanated from his large personal library.46 Precisely where the groaning bookshelves of this small but weighty collection was located in his house we do not know, but it was so well-kept that it brought to mind for Arce y Miranda the deeply learned, but slightly whimsical laws for the governing of libraries attributed to their detractor, Manuel Martí, which included such commandments as:Thou shalt not smite a book with a sharp edge or point. It is not your foe47

As well as being kept in pristine condition, Eguiara's library also held an impressive collection of books printed on both sides of the Atlantic that represented the full gamut of late humanist scholarly practices. Part of it had of course been build up in the course of compiling the Bibliotheca Mexicana. Not only did it include works in Latin and Castilian printed locally, such as Cabrera's Escudo de armas de México and an account of the learned funeral commemorations performed in Mexico City for Philip IV, entitled Llanto del occidente (Mexico City, 1666), but it also contained numerous late-humanist bio-bibliographical encyclopedias that could serve as models for his own project, from the first bibliography of the Americas, León Pinelo's Epítome (Madrid, 1629), to Antonio Possevino's Bibliotheca selecta (Rome, 1593), an attempt to catalog all Counter-Reformation knowledge in response to Conrad Gessner's heretical Bibliotheca universalis.48 In addition to learned bibliography, other late-humanist scholarly practices were also represented in Eguiara's library. Keen to improve his Latin eloquence, Eguiara had collected favorites of the Renaissance schoolroom, like Cipriano Soares’ De arte rhetorica (Coimbra, 1562, etc.) and Juan Luis Vives’ De exercitatione linguae latinae (Paris, 1560, etc.), while classicizing sacred oratory was represented by oratorical collections such as the Orationes (Lyon, 1625, etc.) of the Jesuit botanist and scholar of oriental languages, Giovanni Battista Ferrari. Perusing his library, it is clear that Eguiara wanted to have all registers of Latin at his fingertips, help in which came in the form of Charles du Fresne's Glosarium mediae et infimae latinitatis (Paris, 1678), a guide to Late Antique Latin beloved of Edward Gibbon, and Mario Nizolio's Thesaurus Ciceronianus (Brescia, 1535), a concordance of Ciceronian usage that would have come in handy when composing Neo-Renaissance epistles and orations according to strict Ciceronian usage. The Church Fathers, those sainted scholars who combined pristine Latin and Greek with faultless orthodoxy, were of course also well represented as the forebears of his intellectual project. Furthermore, as a good Christian soldier, Eguiara had to know his enemy, from the marauding Muslims of the Malay Archipelago described in Joseph Torrubia's Disertación historico política, en que trata de la extension de el mahometismo en las Islas Philipinas (Madrid, 1736), to those who made pacts with the devil described in the infamous handbook on witch-hunting, Malleus maleficarum (Speyer, 1487, etc.).49 To these he added the stock tools of his trade as a university theologian, including innumerable saints’ lives, ample works of theology and heavy tomes of canon law.

For Eguiara, this compact collection was just one star in a larger galaxy of libraries in Mexico City to which he had access, many to be found in institutions where he himself had studied over the years. Two blocks north of the cathedral and less than a kilometer and a half from his house was the colegio máximo de San Pedro y San Pablo, which by the time of the expulsion of the Jesuits some thirty years later contained over thirty thousand books. This was itself a stone's throw away from the residential colegio de San Ildefonso, which held an equally impressive number of volumes, in contrast to the university itself, which had little in the way of books.50 Just as volumes could move from Eguiara's to López's library in response to a Latin epistle, so Eguiara and his learned contemporaries could move from library to library across the urban landscape to consult the learned volumes that formed the bedrock of their culture of Christian late humanism.

While many of these institutional libraries had existed for over a century, Mexico City's bibliographical landscape was anything but static. There was a vigorous trade in secondhand books printed on both sides of the Atlantic, while the Viceregal capital was also the main destination for the transatlantic book trade and so enjoyed a steady stream of new books from Europe. This dynamism rested on commercial networks that stretched from Spain across the Americas and beyond. For instance, Domingo Sáenz Pablo (d. 1738) imported books through his relatives in Spain, which he sold in his shop or to other booksellers in Mexico City, and even sent crates of books along the caminos reales and transoceanic trade routes that led to Manila. This vigorous trade in books required wholesalers, distributors and last but not least retailers, and in this vein Olivia Moreno Gamboa has identified thirty bookstores of different shapes and sizes active in Mexico City during the eighteenth century. Some were simply stores that sold books in addition to other merchandize, others specialized in the book trade, while still others, like that of José Bernardo de Hogal in calle de capuchinas, were also print shops. Books were even sold at the market stalls in the parián (the complex built in the plaza de armas beside “A” and “B”).

Conveniently for Eguiara and his learned contemporaries, all the main outlets for books were located in the streets around the cathedral (marked “A”) and the University (marked “50”) in the part of town where most of their number lived.51 Of these the outstanding example was the bookshop of the Inquisition's book inspector, Luis Mariano de Ibarra, located in his house two blocks north from the palacio (marked “B”) on the calle de Santa Teresa. According to its 1750 inventory, it kept a large stock of devotional works, theological treatises and legal texts displayed on book shelves in a series of interconnected rooms. This was in addition to the hundreds of copies of essentials like Cicero's letters and Ovid's Metamorphosis that he kept in stock to supply the students in the city's Jesuit colleges.52 Eguiara could thus order, peruse and purchase books without venturing very far from his usual circuits.

Not only was Eguiara's house part of the larger bibliographic landscape of the city, but it also soon became part of a network of print shops that invigorated Mexico City's self-reproducing learned culture. In compiling his encyclopedic account of learning in Viceregal New Spain, Eguiara had quickly realized that one of the primary impediments to intellectual flourishing in the Americas was the relative paucity of presses. There were, of course, numerous print houses that served the needs of ecclesiastical institutions and the city's universities and colleges. However, there was no press in the whole city he deemed up to the task of producing a majestic Latin folio, like his Bibliotheca Mexicana. Using his family connections in Spain, he acquired type and a press, and began printing his magnum opus “in the house of the author” (in aedibus authoris). If we again consider the location of Eguiara's house within the larger urban geography, this decision comes as no surprise. Among the many shops that lined the calle de San Agustín in the first half of the eighteenth century was the famous Calderón press, which was a hive of activity at least up until the 1730s and continued to produce imprints sporadically until its permanent relocation to the Empedradillo in 1750.53 Just as he shared books and ideas with his neighbor López, it is hard to believe that, as a scholar and ecclesiastic, Eguiara did not have some sort of relationship with the printers who worked a stone's throw away from his house, who inspired him to make his own home into a similar temple to the printed word. At a very profound level, then, the urban landscape informed and shaped Eguiara's scholarly life in a way that few historians have realized, creating local clusters of scholars, print shops and books that in turn were linked to larger networks that stretched across the Viceroyalty and beyond.

The social life of learning in the academia eguiarenseEguiara and his contemporaries were not only avid letter-writers and bibliophiles, whose scholarly achievements rested on interconnected educational institutions and the cultivation of personal friendships with individuals living both in their own city and in other urban contexts in the Hispanic Monarchy. Their scholarly lives were also nourished by other social structures, which shaped their lives and intellectual development. As is well-known, Mexico City was filled with pious social organizations. Of these, the most famous today are the confraternities, which brought together members of Mexico City's different communities and simultaneously served the needs of social contact and eternal life. There were, for example, confraternities for members of the same guild (such as painters like Ibarra, who had a special devotion to Our Lady of Perpetual Help), members of the same caste (such as those of African descent, who founded confraternities devoted to St. Benedict the Moor and Saint Ephigenia of Ethiopia) and members of particular Spanish diasporic groups (such as the Basques (bascongados) who congregated in the confradía de Nuestra Señora de Aránzazu).54

In the case of Eguiara, the Basque confraternity represented an important backdrop to his life as a cleric and scholar. As the child of a father from Vergara and a mother from Anzuola, Eguiara was an active member of the Basque confraternity and even, like his father before him, served as rector on a number of occasions. Like his friendship with López, this membership was facilitated not only by personal links but also by proximity. The confraternity had a chapel in the atrium of the Convent of San Francisco (“M” on map) on the western side of the plaza de armas, conveniently located less than a kilometer from Eguiara's home and a similar distance from the university. Thanks to the considerable commercial wealth of New Spain's bascongados, the chapel was one of the most sumptuous in the city featuring stained glass windows, statues of saints connected to the Basque Country and New Spain (St. Prudence, the Japanese martyr St. Philip of Jesus, etc.), a bejeweled statue of the Virgin of Aránzazu and numerous painting of her miracles and the famous fires that destroyed the churches devoted to her in Oñate.55 This impressive space not only provided a backdrop for Eguiara to interact with his larger networks of friends and relatives, but also served as a theater to hear sacred oratory, an important vernacular scholarly practice for Christian humanists. In turn, Eguiara's frequent visits to the chapel also linked him to larger networks that crisscrossed the city and the Catholic Monarchy as a whole. Particularly prominent among the members of the confraternity were Basques of the merchant class, who connected Eguiara to larger trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific Basque commercial networks, and it is likely that it was these networks that allowed him to purchase the printing press on which he would later produce the Bibliotheca Mexicana.56 Last but not least, membership of the confraternity also allowed Eguiara to make his own mark on the urban landscape through a residential college for female Basque orphans, the colegio de san Ignacio, built on the former marketplace of San Juan (marked “44”), during his rectorship of the confraternity.57

Yet, as widespread and important as these confraternities were, Mexico City was also dotted with other affinity groups, in which self-selecting members dedicated themselves explicitly to learned pursuits. In the case of Eguiara, Cabrera and many of their contemporaries, the most significant of these was the academia de san Felipe Neri, often known as the academia eguiarense, a pre-professional learned academy devoted to theology and humane letters that to date has not received the attention it deserves. Although one of the leading drivers of intellectual life and late-humanist culture in Mexico City, the academia eguiarense was not without precedent. Rather, it was part of a larger phenomenon in the Hispanic branches of the Republic of Letters, whereby universities and colleges loosened their death grip on higher learning, and allowed the formation of academies where students could be drilled in the day-to-day rituals of scholarly life, such as scholastic disputation, delivering sermons and orations, pleading legal cases, and literary competitions, with the ultimate aim of improving students’ performance in university examinations (grados).58 In Mexico City, there were at least three of these academies: two of jurisprudence that met at the colegio de Cristo (marked “48”) and the Jesuit colegio de San Ildefonso (marked “49”), and the academia eguiarense, devoted to theology.59 Although many would later attribute the foundation of the academia eguiarense to Eguiara, he himself tells us that it was founded as a philosophical academy in the first decade of the eighteenth century by two priests of the Oratory of San Felipe Neri, Antonio Pignatelli and Juan Antonio Pérez de Espinosa, who went on to found the Congregation of the Oratory in what is now San Miguel de Allende in Guanajuato.60

Once again, Eguiara's close involvement with this academy was shaped by urban geography. For much of his long life, he lived within a few minutes’ walk of the original church of the Oratory in the calle de San Agustín, where from his earliest days he received moral instruction alongside his brothers, and later would return the favor, delivering numerous moralizing sermons and theological lectures (pláticas).61 Eguiara knew every inch of the Oratory, and all those who walked its cloisters, not just the fathers. Indeed, in the Bibliotheca Mexicana, Eguiara explicitly praised Ignacio Antonio Sandoval, an indio of noble descent, who played the organ, painted and sculpted in the church of the Oratory, and whose consummate skill as a musician and artist Eguiara used to prove that the Indians did not lack natural talent, merely the financial support of suitable patrons.62 The existence of a learned academy at the Oratory was also a beneficial arrangement for both parties. For the Oratorians, it was an opportunity to advance the devotion to San Felipe Neri by supporting a group of clerics who would deliver sermons and compose humanist verses in honor of the Saint as part of the Academy's exercises, and (with any luck) would form a network of alumni in the most influential ecclesiastical circles, whose goodwill might one day serve the interests of the Oratory. Conversely, from the point of view of Eguiara the Oratory offered both a convenient and familiar location and an ideal space for academic exercises in the form of the two aulas on either side of the church usually used for hearing the confessions of the faithful.63 There was, of course, also the added advantage of the Oratory's library, a collection which contained many unique copies of works in print and manuscript that Eguiara examined carefully when compiling the Bibliotheca Mexicana, as well as the presence of the learned Oratorians who could be consulted on particular issues of theology and from time to time also roped into participating in literary and theological exercises as judges.64

Yet, however close Eguiara was to the Oratorians, after fifteen years of meeting in the calle de San Agustín, it was decided that the Academy had to be moved. The reason given by Eguiara again hinged on urban geography. Although the distance between the Church of the Oratorians (marked “21”) and the streets near the plaza de armas, where the University (marked “50”) and the main Jesuit colleges (marked “49” and “S”) were located, was less than a kilometer and a half, it seems students had been struggling to attend meetings due to the time it took to return to their lodgings. However, this was probably not wholly an issue of distance. Quick passage between the two locations was probably also slow-going as the area surrounding the university in the busy market square of plaza del Volador was frequently chaotic, and was also the scene of temporary bull fights and public events of various sizes that in the winter months churned the plaza into an impassable quagmire.65 With this in mind, Eguiara decided to move the meeting place to the University itself, where they could make use of the aula mayor, changing location without changing the conventions set out by its founders or their particular devotion to San Felipe Neri.66

The University's aula mayor (sometimes simply called el general) was in many ways the logical choice for the Academy's new meeting place, as it was the usual site of rhetorical and poetical exercises and an inspiring room for young scholars. The space, as Eguiara knew it, was the product of renovations that had occurred in the age of the famous polymath Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora. Students and masters entered from the north side through two vast wooden doors into a hall that was 132 feet long by 33 feet wide and 42 feet high, decorated with arches and Doric columns and lit from the south side by four windows. On the west wall there was a door that opened into an antecapilla featuring a wooden platform with seats for the voting members of the University decorated with pendatives (pechinas) enclosing paintings of the St Ambrose, St. Jerome, St. Augustine and St. Gregory the Great.67 Other exemplary figures also looked down on the members of the Academy during their meetings. As the eighteenth century Mexican mathematician, José Antonio de Villaseñor (c. 1695–1750), described it in his Teatro Americano (1746–48): “there are portraits done from life of many of the illustrious alumni of the Royal University, but not of all of them because full length portraits would not fit in the already jam-packed room. As a result, only alumni who were given miters and not just holders of minor ecclesiastical offices, judges or other dignitaries are depicted, not to speak of the number of doctors, who are beyond count and spread out across the whole kingdom and beyond.”68 There could be no better place to hold meetings of a learned academy whose members aspired to similar fame.

Whether in its earlier home in the Church of the Oratory or later at the University, the Academy met twice per week during the academic year for some fifty years to cultivate Christian humanism. The first of these two weekly meetings was devoted to scholastic and moral theology, during which Eguiara or some other leading figure might give half-hour lectures on Peter Lombard or Aristotle for the benefit of those working toward degrees in theology. Members might also engage in scholastic disputation, or organize special events. On one occasion, Eguiara presided over a full day's academic exercises performed by Juan Miguel de Carballido y Cabueñas, doctor of theology and erstwhile rector of the University, who defended four theses from scholastic theology in the morning, subjecting himself to the questions of the Oratorians, and in the evening defended four more theses on moral philosophy in the presence of the Oratorians and other doctors of theology. On another occasion, Pedro de la Carrera gave a lecture on Genesis III.24 (“So he drove out the man; and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.”), taking questions from all-comers, quite a feat, when you consider regular attendees included seven doctors of theology and numerous former and current students of theology and another subjects at the University.69 Once the Academy moved to its new location sometime in the late 1720s, Eguiara and his coterie also began holding these day-long events in the aula mayor of the university, where events were held at which members would defend all of scholastic theology in the morning and in the evening.70

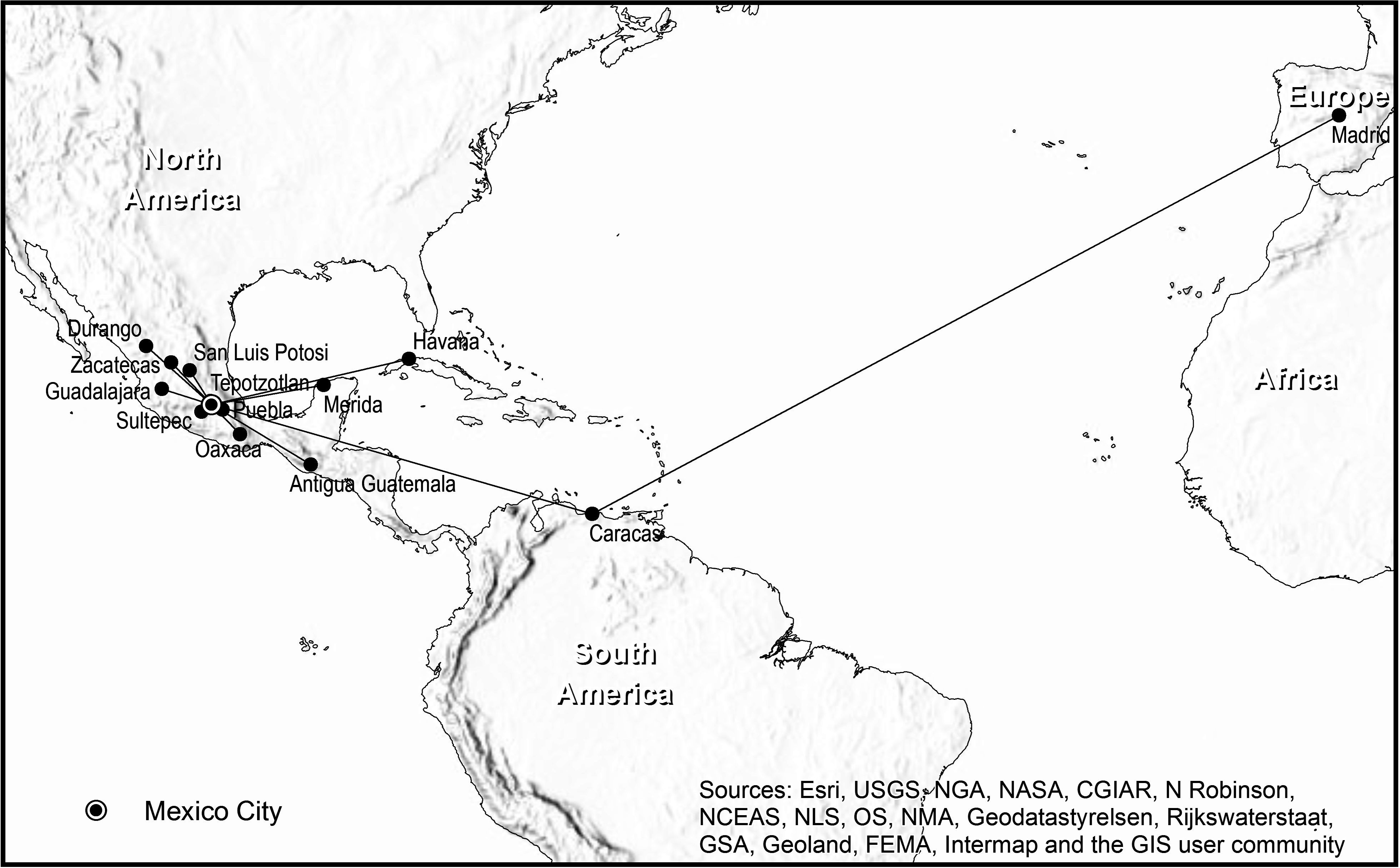

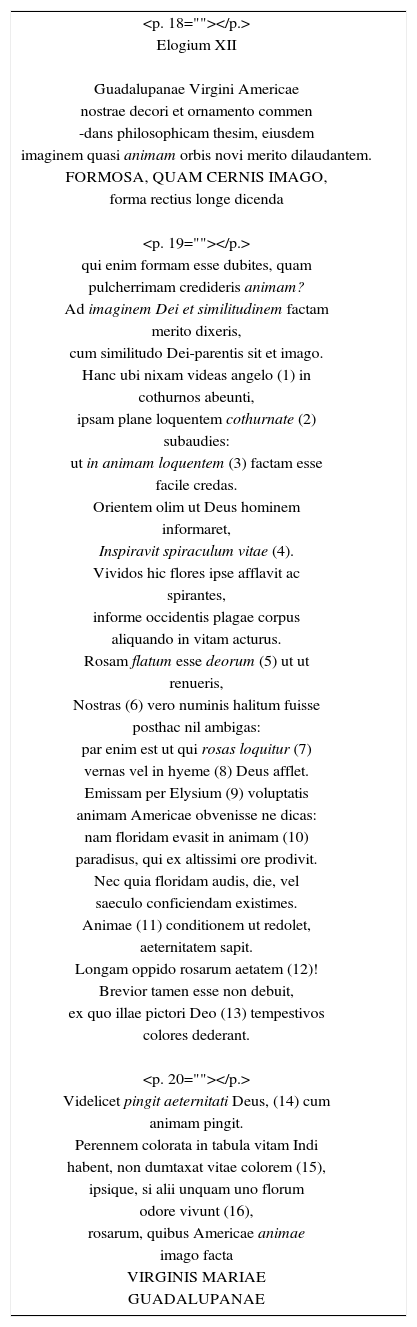

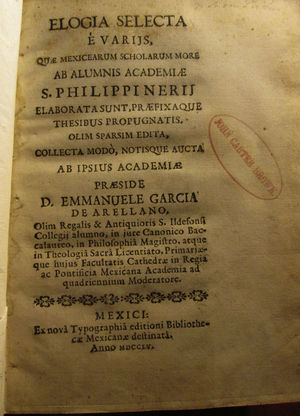

Late-humanist eloquence in prose and verse (amoenae litterae) was the focus of the second of the Academy's weekly meetings. Although precise details of these meetings are scarce, we know that over the years Eguiara himself delivered seventeen panegyric orations at the Academy. These were pious classicizing speeches (either in Latin or the vernacular) that mixed sacred and humane learning while privileging compelling arguments over theological niceties.71 In Eguiara's Academy, other late humanist scholarly practices related to university life were also cultivated. In the early modern Hispanic university, it was the convention to append a Latin dedication to every thesis that was defended, and the members of Eguiara's Academy took this task particularly seriously, printing a collection of their best examples in 1755 (Fig. 4).72 These dedications took the form of tituli, a late-renaissance development of the classical inscription addressed to a particular saint or Marian apparition. According to an anonymous rhetorical manuscript copied in Mexico City in 1701, a titulus should consist of a brief description of the name, distinctions and gifts of the celestial patron, and should also include numerous epithets associated with the saint served with a liberal helping of erudite references.73 The members of the academia eguiarense followed these instructions to the letter. Their long tituli, which frequently stretched upwards of 40 lines, were dedicated to the Trinity, the Eucharist, the Virgin of Aránzazu, the Virgin of Guadalupe, Santa Rosa de Lima, and numerous other (especially Jesuit) saints, and were filled with classical, patristic and biblical learning, which they carefully glossed in copious footnotes. For instance, in a titulus dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe, God, the ultimate author of the image on Juan Diego's tilma, was said to “paint for eternity when he paints the soul,” an illusion to Zeuxis, the ancient Greek painter, who responded to Agatharchus’ complaint that he painted so slowly, by saying that he was painting “for eternity” (Appendix).74 The sort of classical learning that Eguiara possessed was clearly common to many if not all the members of the Academy, which united the erudite youth of Mexico City to engage in late humanist pursuits.

Title-page of Arellano (1755). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Continuing in the late humanist literary vein, Eguiara also oversaw poetic competitions (certámenes poéticos) at the Academy on feast days, such as Christmas. Although no evidence survives of what exactly took place during these poetic competitions, we can glean much from similar events held at the University. For instance, in 1724 Eguiara was part of the commission charged with organizing and judging a certámen poético to celebrate the accession of the ill-fated King Luis I (d. August 31, 1724). According to the cloister records, the event was to include “a masquerade (máscara) by the students, fireworks and a poetic competition, without sparing any pomp that were necessary on such occasions.”75 This was of course much more lavish than the simple affairs organized by the academia eguiarense, but reflected the larger genre of poetic displays and their importance within Eguiara's scholarly world, and so is worth recounting in detail.

In the weeks before the competition proper, students, faculty and alumni built triumphal chariots (carros triumphales) reminiscent of those ridden by Roman generals into the Eternal City following significant victories. In the presence of the Viceroy and a large crowd of elite and plebian onlookers, four chariots entered the main atrium of the university, each decorated according to a theme and accompanied by attendants in costume, while other students milled around dressed as crows and parrots. The first chariot was dedicated to music and was pulled by a donkey, a pig, a goat and a ram, representing (in a purposefully burlesque and ridiculous way typical of the early modern festival culture) the unity of all of nature in celebrating the royal coronation. This was then followed by a chariot that carried a tub filled with water that sloshed out onto the ground and provided the ammunition for a troop of students dressed as comical soldiers armed with water pumps (melecinas) who sprayed the audience, and called attention to the many victories over the enemies of the Catholic Monarchy represented by a painting of a Turk on all fours on the side of the chariot. The third chariot carried a butcher chopping up pork accompanied by students dressed as cats on horseback and other cats who handed out meat to the common people in the crowd, in a way reminiscent of the “food chariots” (carri cuccagna) in Spanish Naples.76 The final chariot featured an old woman giving birth to an infant with painted images of volcanos producing new land, representing the hope that Luis I would live for eternity and give birth to heirs. Each of these chariots had inscriptions on the front in Castilian décimas that explained their meaning, and after their arrival, an alumnus of the university recited a comical poem of welcome to the Viceroy. The event then turned more serious, as students entered dressed as classical heroes and gods accompanying a chariot carrying a five-meter-tall model of Mount Helicon, on which sat a figure dressed as an Apollonian Luis I surrounded by the nine Muses, Hercules and other classical figures, each accompanied by celebratory inscriptions in Latin and Castilian. Clio, the muse of history, then recited a loa accompanied by Indians playing bugles and drums, which drew the whole event to a close.

A few days after this lavish classicizing carnival came the crowning moment for the devotees of late humanist at the University, the poetic competition itself, and it is here where the parallels with Eguiara's Academy were probably strongest. Submissions were sought and after three days of discussion, the committee returned the results. For the occasion, the halls of the university were decorated with bunting and in the middle of the main atrium an ephemeral column reminiscent of one of the pillars of Hercules was erected with statues of Philip V and Luis I. Eguiara himself also wrote Latin and Castilian inscriptions on the famous royal motto ne plus ultra that adorned the entranceway of the chapel. The results of the three sub competitions to compose verses in a variety of Latin and vernacular verse forms were then announced, and the winners recited their entries. These events attracted the very best late humanist scholars. In the second of these (to compose ten lines in praise of Luis I in Iambic Senarii) the author of the verses on the frontispiece of the Escudo de armas de México, Cayetano de Cabrera y Quintero, was edged out by José Antonio de Villerías y Roelas (1695–1728), who that very year had finished his famous Latin epyllion on the Virgin of Guadalupe. Shortlived fame was not the reward on offer in the poetic competition; late humanist Latin could also be lucrative. For instance, Villerías won a silver plate inscribed with Castilian verses in praise of the poet. The runner-up received a smaller silver plate, while the third placed poet received a candle wick cutter (tijeras de despabilar), both with somewhat less laudatory inscriptions. In other competitions, cocoa pods (una buena molienda de chocolate) and other sorts of silver tableware were given are prizes. Significantly, both Cabrera and Villerías also won prizes for their Castilian verses in the third competition. Skill in Latin poetics was clearly highly prized in and of itself, but it also complemented and arguably bolstered vernacular poetics, both of which were cultivated in the academia eguiarense, the leading gymnasium for training young scholars to take the prizes at competitions such as these.77

As all the exercises undertaken at Eguiara's Academy directly mirrored contemporary university practices, the professional advantages that could accrue from membership should not be underestimated. Within the ecclesiastical hierarchy, Christian humanism was both an ornament and a practical necessity.78 It was in the academia where students and scholars got the face-to-face training for university examinations and the learned displays of Latin eloquence required for oposiciones for chairs at the university, canonries and other ecclesiastical prebends. Even to receive a doctoral degree in theology, the prerequisite for high office in the ecclesiastical and civil administration, not only was it necessary to perform the theological exercises to receive the grado itself, but the candidate also had to deliver short Latin orations requesting the degree, while the ceremony for the doctorate began with a vejamen, a celebratory work in classicizing Castilian prose or verse, by the maestrescuela.79 All sorts of printed works were also prefaced by Latin verses that brought considerable prestige in learned circles and allowed the name of the poet to stand beside those of the important ecclesiastical and secular officials who wrote the pareceres and other prefatory materials. In short, the seemly recherché activities of the academia eguiarense were anything but obscure. Rather, they were thoroughly pre-professional, and seem to have been highly effective in propelling members of the Academy into high-powered careers. Indeed, Eguiara boasted in the Bibliotheca Mexicana that current and former members of his Academy could be found holding chairs at universities and in positions of power within the church in both New and Old Spain.80 These included: Antonio de Folgar y Amunarris, canon of collegiate church of our Lady of Guadalupe; Antonio de Cárdenas y Salazar, archdeacon of Oaxaca; Cosme Borruel, who was in the service of the bishop of Guadalajara and taught in the college of Zacatecas; Antonio Cardoso y Comparán, the parish priest and ecclesiastical judge of the important mining town of San Luis Potosí; and Bartolome Felipe de Ita y Parra, who became one of the most famous preachers in New Spain.81 Eguiara himself would, of course, eventually be elected bishop of the Yucatán, and Cabrera (named secretary of the Academy in 1722) would be made chaplain to the Viceroy and Archbishop of Mexico City, Juan Antonio de Vizarrón y Eguiarreta.82 The mixture of piety, eloquence and erudition cultivated by Eguiara and his fellow academicos thus had its rewards, and made their learned social group into an important feature of the intellectual geography of the Viceregal capital during the first half of the eighteenth century.

ConclusionThe lives of urban-dwelling letrados like Eguiara, Cabrera and López did not play out simply on the printed or manuscript page. Rather, they inhabited multiple overlapping social spheres, and urban and inter-urban spaces that profoundly shaped how they consumed, produced and disseminated late humanist culture. These can fruitfully be understood on a variety of scales from the transatlantic or transcontinental epistolary network to the learned friendship that played out over a distance of only a few city blocks or across the table at one of Eguiara's dinner parties.

As the spatial turn asserts itself in Latin American cultural history, it seems that our current obsession with long-distance connectedness has privileged the telescope over the microscope, when the application of both is, of course, necessary to build a truly complete picture of these lives of learning. In this Russian doll of possible scales, the city with its clustering of scholars, educational institutions and libraries emerges an important, if not the most important, unit of analysis. Yet, this comes with an obvious caveat. Urban spaces were not sealed, but characterized by a constant ebb and flow of individuals, books and letters and the social and infrastructural links that bound them to the rest of the Viceroyalty, the Hispanic Monarchy and the Republic of Letters at large.

As a result of the pervasiveness of late humanist culture, this urban space was frequently also imagined as a calque of ancient Rome (as well, of course, as of Jerusalem and occasionally Athens). Eguiara and López exchanged letters as the Mexican incarnations of Cicero and Atticus, while chariots reminiscent of Roman imperial triumphs rolled through the University to celebrate the accession of Luis I, to name but two examples. When read within the context of well-known classicizing elements in city design and architecture, and the well-known Neo-Roman elements of other civic rituals, it is little wonder that contemporaries likened the highland metropolis to the Eternal City.83 To our understanding of Mexico City as the theater of multiple small- and large-scale scholarly interactions, we must also add this imagined geography.

Finally, it bears underscoring that the complex lives of learning led by the letrados of eighteenth-century Mexico City show that the cultural landscape of their New World metropolis was not just a dim reflection of Europe's “lettered cities.” Rather, Mexico City and the American branches of the Republic of Letters were self-reproducing and self-referential cultural spheres, akin to the stars in the “constellations of print-shops” that Byron Hamann has identified in his study of the global reception of Nebrija's grammar.84 Furthermore, while cities were, of course, heavily Hispanized, both ethnically and culturally, this urban world of learning was not isolated from the diverse population of city and the Viceroyalty, as López's teaching at the colegio seminario de San Gregorio and the Indian artisan in the background of the academia eguiarense show. Novohispanic late humanism, then, must be understood within these wider spatial, social and cultural contexts. Only then can we do justice to the richness of intellectual life in the Rome of the Americas.

FundingDavid Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University.

| <p. 18=""></p.> |

| Elogium XII |

| Guadalupanae Virgini Americae |

| nostrae decori et ornamento commen |

| -dans philosophicam thesim, eiusdem |

| imaginem quasi animam orbis novi merito dilaudantem. |

| FORMOSA, QUAM CERNIS IMAGO, |

| forma rectius longe dicenda |

| <p. 19=""></p.> |

| qui enim formam esse dubites, quam |

| pulcherrimam credideris animam? |

| Ad imaginem Dei et similitudinem factam |

| merito dixeris, |

| cum similitudo Dei-parentis sit et imago. |

| Hanc ubi nixam videas angelo (1) in |

| cothurnos abeunti, |

| ipsam plane loquentem cothurnate (2) |

| subaudies: |

| ut in animam loquentem (3) factam esse |

| facile credas. |

| Orientem olim ut Deus hominem |

| informaret, |

| Inspiravit spiraculum vitae (4). |

| Vividos hic flores ipse afflavit ac |

| spirantes, |

| informe occidentis plagae corpus |

| aliquando in vitam acturus. |

| Rosam flatum esse deorum (5) ut ut |

| renueris, |

| Nostras (6) vero numinis halitum fuisse |

| posthac nil ambigas: |

| par enim est ut qui rosas loquitur (7) |

| vernas vel in hyeme (8) Deus afflet. |

| Emissam per Elysium (9) voluptatis |

| animam Americae obvenisse ne dicas: |

| nam floridam evasit in animam (10) |

| paradisus, qui ex altissimi ore prodivit. |

| Nec quia floridam audis, die, vel |

| saeculo conficiendam existimes. |

| Animae (11) conditionem ut redolet, |

| aeternitatem sapit. |

| Longam oppido rosarum aetatem (12)! |

| Brevior tamen esse non debuit, |

| ex quo illae pictori Deo (13) tempestivos |

| colores dederant. |

| <p. 20=""></p.> |

| Videlicet pingit aeternitati Deus, (14) cum |

| animam pingit. |

| Perennem colorata in tabula vitam Indi |

| habent, non dumtaxat vitae colorem (15), |

| ipsique, si alii unquam uno florum |

| odore vivunt (16), |

| rosarum, quibus Americae animae |

| imago facta |

| VIRGINIS MARIAE |

| GUADALUPANAE |

NOTE

- (1)

MARIA in imagine Guadalupana ostenditur pede innixa angelo.

- (2)

Nempe cothurnus accipitur pro sublimi dicendi genere, ut Virgilius Ecloga 8<.10>: Sola Sophocleo tua carmina digna cothurno.

- (3)

Ita vertit Chaldea paraphrasis illud: factus est homo in animam viventem (Gen. 2.7).

- (4)

Genesis, 2.7.

- (5)

Ita vocavit rosam Anacreon poeta.

- (6)

Nempe quas Maria tradidit Indo, et quibus (ut videtur) quasi colore usus Deus imaginem depinxit Guadalupanam.

- (7)

Vide superioris elogii notam n. 4 <Rosas loqui dicitur qui eloquens est: eloquentes Trojanorum legatos lilia comedisse ait Homerus.>

- (8)

Hyemali tempore apparens virgo rosas Guadalupanas protulit.

- (9)

Elysium, campus, in quo dicebantur esse animae a corporibus solutae, Virgilius, Aeneidos 5<.735>.

- (10)

Quasi indicet tot ex ore prodiisse flores et rosas, ut factus sit paradisus.

- (11)

Nimirum, rationalis, quae immortalis est, et aeterna.

- (12)

Alludit contra illud Idyllia 14.43>: quam brevis una dies, aetas tam longa rosarum.

- (13)

Deo miraculose pingenti imaginem in Indi quasi pallio, in quod rosae missae fuerant a virgine, sese in conspectum dante, mittenteque illas velut signum ad espiscopum Mexicanum.

- (14)

Diu pingo, quia aeternitati pingo, de se Zeuxis aiebat, rogatus cur tam diu haereret in imaginibus.

- (15)

Alludit ad opinionem eorum, qui Indos olim ita parvipendebant, ut viderentur illis non concedere nisi vitae rationalis colorem.

- (16)

De viventibus solo odore, vide Elog <ae> 3 not <am> num <ero> 13, et citatum ibi <caelium> Rhodigin. </caelium> </ero> </am> </ae>

Stuart M. McManus. Received his doctorate in history from Harvard University in 2016, and is currently at postdoctoral fellow at the Stevanovich Institute on the Formation of Knowledge at the University of Chicago. His research centers on the global monarchies of the Iberian Peninsula, especially in New Spain and Iberian Asia, and on the role of “classical” traditions in empire building. He has published widely on Latin American, Greco-Roman and early modern European cultural history.

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

On the Virgin of Guadalupe, see Peterson (2014) and Conover (2011). The epidemic is described in Molina del Villar (2001).

On Cabrera and Ibarra, see Mues Orts (2001); Mues Orts (2006, pp. 70–82); Toussaint (1965). On Troncoso, see Donahue-Wallace (2000, pp. 65–7).

The most notable treatments are Brading (2001, pp. 131); Escamilla (2012, p. 592). The presence of Cabrera was identified by Orts in her thesis: Mues Orts (2009, pp. 199–204, esp n. 92).

The best biographical work on Cabrera remains: Cabrera y Quintero (1976, pp. I-XCV).

Rama (1984). In early modern Castilian, there are two meanings of the word letrado, one general meaning of any highly literate individual, and another of a judge who holds a degree in law: Pelorson (1980, pp. 15–20). On the slipperiness of the qualifications required for a position as a judge, see Herzog (1994).

For important steps in this direction see Gutiérrez and Romero (1994) and Rubial Garci¿a (1998, pp. 14–16).

Cf. Plutarch, Numa, 13.2. Mues Orts (2009, p. 203 n. 95).

Cayetano (1746), fontispiece:

Brading (1991). There are, of course, some important exceptions: Cañeque (2004); Merrim (2010). There are perhaps more examples for the South American case: Osorio (2008); Safier (2008).

Grafton (2012, p. 38); Hammsterstein (2000). The earliest work in Mexico on late humanist culture is roughly contemporary with that of German scholars of Späthumanismus:Méndez, 1937; Trunz, 1931.

Some moves in this direction have been made: Nemser (2014), Ramírez Méndez (2012). The relationship between the history of science and urban infrastructure has studied by Candiani (2014). For ecclesiastics in general, see Ganster (1986).

The most extensive treatment of the academia eguiarense to date is: Rovira (1995, pp. 624–5).

Vargas (1987, pp. XVIII–XX). Menegus and Aguirre (2006); Díaz Schmidt (2012, 50–57); Villella (2016, pp. 200–203). Villaseñor y Sánchez (1980, 133–134).

Undated letter from López to Eguiara, BNM, ms 329, folios 173r-v (173r).

Undated letter from López to Eguiara, BNM, ms 329, folios 173r-v (173r).

Undated letter from Eguiara to López, Biblioteca Nacional de México (henceforth BNM), ms 329, folios 139r-140v (139r).

Eguiara was, of course, also one of the staunchest defenders of traditional university culture and the perennial value of scholastic disciplines in particular: Beuchot, 1993.

Undated letter from López to Eguiara, BNM, ms 329, folios 125r–130r.

Arce y Miranda, 1761, h. 1v–2r.

Undated letter to López from Eguiara, BNM 329, folios 139r–140v (140v).

Undated letter from López from Eguiara, BNM ms 329, folio 181r.

Eguiara's correspondence is described in detail in Castro Morales (1961).

Eguiara y Eguren (1755), I, folio 34br. This contrasts the view of Brading (1991, p. 389).

Letter from Eguiara to Fray Marcos Linares dated November 20, 1745, BNM, ms 756, folios 64v-65r; Castro Morales (1961, pp. 19–22); Eguiara y Eguren (1755, 158). On the routes taken by correspondence, see Sellers-García (2014, pp. 80–82).

Arce y Miranda, 1761, h. 2r-v. This is discussed in Eguiara and Torre (1986, p. LXX).

Arce y Miranda, 1761, h. 2v-3r.

Arce y Miranda, 1761, h. 3r Martí, 1735, II, pp. 401–03(402): “II. NE CAESIM PUNCTIMVE FERITO. HOSTIS NON EST.” Martí’s laws for his library were so popular in Mexico City that they were appended to the catalog of the cathedral library BNM, ms 6412.

Luque (1995); von Germeten, 2006. Zaballa Beascoechea, 1996. Bascongados included those born in the Lordship de Vizcaya, the Provinces of Alaba and Guipusqua and the kingdom of Navarre with the Basque language also playing an important role in the formation of identity.

Eguiara and Torre (1986), CCCL.

Eguiara y Eguren (1755, p. 11). For an account of the foundation of the Oratory in Mexico (although not of the Academy), see Gutiérrez Dávila (1736, pp. 15–44).

Torre (1993, pp. 171–2). Various sermons and lectures performed in the Oratory by Eguiara are preserved in BNM, ms 762.

Eguiara y Eguren (1755), folio 32bv.

Eguiara y Eguren, 1747, folios §2v–§3r. Arellano, 1755, folio §2br.

Arellano (1755), folio 3r-v. Trascribed in Eguiara and Millares (1944, pp. 44–45).

Rhetoricorum libellus, BNM, ms 33, folios 36r-39r (37v).

Guerra y Morales (1724, pp. 3–8, 133–192, 210–212, 220–222, 246). On Villerías, see Osorio Romero (1991).

On the tradition of Christian humanism, see Stinger, 1977; Maryks, 2008.