Although previous cause-related marketing literature has examined the role of the nature of the product and the perceived fit between the product and the cause, there is no clear consensus yet regarding the effect of these variables. This study contributes to existing literature by shedding light on the role that these two key factors have on consumer response. A 2 (utilitarian products vs. hedonic products)×2 (perceived fit: high vs. low) between-subjects factorial design was used to test the hypotheses. The results indicate that the nature of the promoted product used in the cause-related marketing campaign influences both brand attitude and purchase intention. Specifically, the attitude towards the brand was greater for the hedonic products than the utilitarian ones. By contrast, cause-related marketing campaigns linked to utilitarian products lead to higher purchase intentions. In addition, perceived fit between the product and the cause seems to play a key role, as this variable positively influences both the credibility of the campaign and the attitude towards the brand. The results provide useful guidelines for marketers in designing their cause-related marketing initiatives.

Cause-related marketing (CRM) initiatives have become increasingly popular among organizations. This strategy implies supporting a social cause to promote the achievement of marketing objectives (Barone, Norman, & Miyazaki, 2000). CRM implementation can be undertaken in different forms (Gupta & Pirsch, 2006a; Liu & Ko, 2011). One of the most common forms involves the donation of a portion of the corporation's profits from each product sold to a cause. In this sense, CRM is defined by Varadarajan and Menon (1988, p. 60) as “the process of formulating and implementing marketing activities that are characterized by an offer from the firm to contribute a specified amount to a designated cause when customers engage in revenue-providing exchanges that satisfy organizational and individual objectives”.

Supporting a specific cause can have several advantages. For instance, cause marketing programmes allow companies to create a link with customers and show a commitment to social responsibility. Unlike other marketing communications tools, CRM is also a powerful way to reach consumers on an emotional level (Roy, 2010). This promotional strategy can improve and sustain a favourable image and reputation among consumers, establish differentiation from competitors and add value to the brand (Brown & Dacin, 1997; Wymer & Samu, 2009). All these benefits can, in sum, positively influence consumer attitude and purchase behaviour. However, recent research has shown that, compared to other corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions, such as sponsorship or philanthropy, CRM activities are more likely to be viewed with suspicion (Lii & Lee, 2012; Sheikh & Beise-Zee, 2011), as CRM initiatives generally require consumers to make a purchase; therefore, the link between the cause and the company's profits can result in a less favourable evaluation.

Given the relevance and business emphasis on using CRM initiatives, it is important to explore the main factors associated with successful CRM campaigns. Among the multiple factors that may have a bearing on the effectiveness of CRM, two are of particular interest: the type of product and the perceived fit between the product and the cause. The evaluation of CRM initiatives is likely to depend on the type of product used (i.e. hedonic vs. utilitarian) (Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). Likewise, perceived fit, which refers to the degree of proximity or congruence between the product and the cause, has been assumed to be one of the most influential with respect to the ultimate success of the partnership (Lafferty, 2007). Controversy exists, however, regarding the influence of these variables. For instance, while some authors have found that consumer response to CRM is more favourable when the products are hedonic rather that utilitarian (Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998), others have not replicated these results (Subrahmanyan, 2004; Wymer & Samu, 2009). Likewise, advice on the level of fit between the product and the cause is mixed, with some calling for a high level of fit and others advocating a moderate or low product-cause fit level (Barone et al., 2000). In addition, both factors (the type of product and perceived fit) can simultaneously influence three levels of consumer response: cognitive, affective and behavioural (Roy, 2010). Research, however, has generally addressed the analysis of consumer responses individually.

In this context, this study assesses whether the nature of the product and the fit between the product and the cause influence: (1) the credibility of the CRM campaign (cognitive consumer response); (2) the attitude towards the brand (affective consumer response); and, (3) the purchase intention (behavioural consumer response). In addition, we aim at comparing the nature of the product, that is to say, hedonic and utilitarian products in order to better understand the results of this study.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. First, we present the theoretical background of the study and formulate the hypotheses. We then describe the research method, followed by an analysis of the empirical results. Finally, conclusions and implications for researchers and managers are provided, along with the limitations of the study and directions for future research.

Literature reviewAs with other managerially controllable factors, such as price, distribution and advertising, CRM campaigns influence cognitive, affective, and behavioural consumer responses (He, Zhu, Gouran, & Kolo, 2016; Huertas-García, Gázquez-Abad, & Lengler, 2014; Roy, 2010). To increase the efficacy of CRM, the growing literature on this topic has analyzed the impact that several factors have on consumer responses to these initiatives.

For instance, some authors have studied cause characteristics, such as the familiarity, the importance and the geographic scope of the cause (Cui, Trent, Sullivan, & Matiru, 2003; Grau & Folse, 2007; Hou, Du, & Li, 2008; Lafferty & Edmondson, 2009). Researchers have also explored the role of the variables related to the campaigns, such as the donation size (Chang, 2008; Moosmayer & Fuljahn, 2010; Pracejus, Olsen, & Brown, 2003, 2004), the clarity of the message (Simmons & Becker-Olsen, 2006), the dominance or emphasis given to the cause in the message (Samu & Wymer, 2009), or the duration of the campaign and the amount of resources invested (van den Brink, Odekerken-Schröder, & Pauwels, 2006). Similarly, other researchers have analyzed the influence of characteristics relating to the company, such as its corporate credibility (Kim, Kim, & Han, 2005; Lafferty, 2007), or related to the non-profit organization, such as its image (Arora & Henderson, 2007). Finally, other authors have examined the impact of consumer characteristics on their responses to CRM, such as consumer scepticism (Vanhamme & Grobben, 2009), concern for appearances (Basil & Weber, 2006), consumers’ temporal orientation (Tangari, Folse, Burton, & Kees, 2010) and other socio-demographic variables (Cui et al., 2003).

While these previous studies have offered new insights into consumer responses to CRM, there is a general consensus among scholars that more research is needed (Aldás, Andreu, & Currás, 2013; Lafferty & Edmondson, 2009). Specifically, among the multiple variables that may affect the influence of a CRM programme, two are of particular interest: the nature of the product, and the fit between the product and the cause. These variables have been identified in prior research as potentially relevant factors influencing CRM success (Lafferty, 2007; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). However, as noted earlier, the results are still controversial. In addition, as these variables are under companies’ control, they are relevant to managers when designing CRM campaigns. In the next section, we explore how these two variables may influence cognitive, affective and behavioural consumer responses to CRM programmes.

Nature of the product: hedonic vs. utilitarianThe evaluation of CRM initiatives is likely to depend on the type of product used (i.e. hedonic vs. utilitarian). While hedonic products, such as ice cream, chocolates or concert tickets, are generally linked to experiential consumption, utilitarian products, such as laundry detergent or toothpaste, are viewed as more functional and instrumental. Therefore, hedonic products are judged in terms of how much pleasure they provide, whereas utilitarian products are judged in terms of how well they function.

Previous research has shown that the success of CRM campaigns is higher when the strategy is used with hedonic products rather than utilitarian ones (Chang, 2008; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). For instance, Strahilevitz and Myers (1998) found that donations to charity were more effective for promoting frivolous products (i.e. hedonic products) than in promoting practical products (i.e. utilitarian products). On the contrary, monetary incentives (i.e. price discounts) were preferred when they were bundled with utilitarian or practical products. This result can be explained by the fact that hedonic products are more likely than utilitarian products to arouse both pleasure and guilt (Kivetz & Simonson, 2002; Zheng & Kivetz, 2009). According to the field of social psychology, guilt is a negative emotion that a person may wish to overcome by means of some prosocial behaviour (e.g. Batson & Coke, 1981). Therefore, the feeling of guilt can be mitigated if the hedonic purchase is linked to a cause. In contrast, CRM campaigns linked to practical products tend to generate fewer emotional responses. Thus, the evaluation and purchase decisions for these types of products are usually more rational and focused on cues related to the product itself (Chang, 2008).

Based on the reasoning above, it is expected that consumers will demonstrate more positive cognitive, affective and behavioural responses when CRM initiatives are used in hedonic products. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:H1 CRM linked to hedonic products (vs. utilitarian) will lead to: (a) higher campaign credibility; (b) a more positive attitude towards the brand; and (c) higher purchase intention.

Perceived fit refers to the perceived degree of proximity or congruence between the promoted product and the cause. The influence of perceived fit has been studied within multiple research streams in marketing, such as brand extensions (e.g. Aaker & Keller, 1990; De Jong & van der Meer, 2015; Völckner & Sattler, 2006), co-branding (Simonin & Ruth, 1998), corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Currás-Pérez, Aldás-Manzano, & Bigné, 2012; Pérez & Rodríguez del Bosque, 2013) and sponsorships (Simmons & Becker-Olsen, 2006; Speed & Thompson, 2000). Drawing from this literature, previous studies have also analyzed the importance of fit with respect to the CRM campaign's success (Bigné, Currás-Pérez, Ruiz-Mafé, & Sanz-Blas, 2012; Kuo & Rice, 2015).

In order to achieve suitable results Lafferty, Goldsmith, & Hult (2004, p. 512) recommend distinguishing between functional and brand fit. Product-category is considered a functional fit and it is determined in function of the characteristics, attributes and functions of the type of product of the brand and the type of social cause supported. Brand-name fit refers to how comfortable consumers are with the cause-brand pairing and it is related with the congruence between the image of the brand and the social cause. More, the same brand may have different product categories. Considering differences between types of fit is necessary as these two types of fit may have different influence on consumer perceptions and attitudes (Currás-Pérez et al., 2012).

However, unfortunately literature too often has not differentiated between functional (product category) and brand (image) fits. This misunderstanding can be the reason of identifying ambivalent results in former researches, and for such reason within the CRM literature, there is a lack of consensus regarding the level of fit a brand, product or company should have with a cause.

While some researchers posit that high perceived fit improves the results of campaigns, others suggest that low fit is more effective. Specifically, some studies have found that high perceived fit can negatively influence consumers’ brand perceptions. This negative effect is due to the fact that CRM campaigns with high fit can be viewed by consumers as opportunistic (Drumwright, 1996; Ellen, Mohr, & Webb, 2000). However, most works have revealed the opposite. In general, high fit has been proven to positively affect different factors, such as product choice (Pracejus & Olsen, 2004; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998), attitude towards the brand (Bigné, Currás-Pérez, & Sánchez-García, 2009; Samu & Wymer, 2009), and attitude towards the campaign (Barone et al., 2000). As such, higher levels of perceived fit between the product and the cause will lead consumers to perceive the company as being more expert, and favour the transfer of positive feelings and beliefs about the cause to the brand (Ellen, Webb, & Mohr, 2006; Hoeffler & Keller, 2002). Likewise, a high fit can explain why an organization is supporting a cause (Sheikh & Beise-Zee, 2011). Therefore, it is suggested that higher levels of fit will improve the credibility of the association between the company and the cause, as well as the consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions (Gupta & Pirsch, 2006b; Pracejus & Olsen, 2004; Samu & Wymer, 2009). In contrast, lower levels of fit are likely to generate weaker attributions of the brand's motive and perceptions of brand credibility, and lead to negative attitudes towards the brand (Becker-Olsen, Cudmore, & Hill, 2006; Rifon, Choi, Trimble, & Li, 2004). The above discussion leads to the following hypothesis:H2 High perceived fit between the product and the cause will have a positive effect on: (a) campaign credibility; (b) the attitude towards the brand; and (c) the purchase intention.

In the design of the study we have followed the recommendations made by Lin, Lu, and Wu (2012) to analyze interactions between product types and other related variables. A 2 (utilitarian products vs. hedonic products)×2 (perceived fit: high vs. low) between-subjects factorial design was used in this study to test the proposed hypotheses.

Experimental stimuliThree pretests were conducted to identify the products, brands and causes to be used in the study. The objective of the first pretest was to choose the products and causes. First, a group of undergraduate students (n=46) indicated, from a list of 20 products, the degree of utilitarianism or hedonism on three seven-point bipolar scales proposed by Wakefield and Inman (2003) (1=practical purpose/7=just for fun; 1=purely functional/7=pure enjoyment; 1=for a routine need/7=for pleasure). Among them, four products were chosen: milk and printers as the utilitarian products (meanmilk=3.01 and meanprinter=2.07) and chocolates and Mp3 players as the hedonic ones (meanchocolates=5.88 and meanMp3=5.57). To enhance the generalizability of the results, the study used both fast-moving consumer goods and durable goods for each type of product (utilitarian products: milk and printers; and hedonic products: chocolates and Mp3 players). Next, the same group of students (n=46) rated the familiarity (F), trust (T) and image (I) of a list of eight causes, again using seven-point scales. We wanted the selected causes to be well-known to respondents (Robinson, Irmak, & Jayachandran, 2012), and from different categories in order to facilitate the design of the scenarios (high fit vs. low fit). Therefore, two causes were selected: Red Cross (F=5.91; T=5.69; I=5.80) and Greenpeace (F=5.58; T=4.94; I=4.88).

The purpose of the second pretest was to choose a brand for each product category (i.e. milk, printers, chocolates and Mp3 players). In line with previous research, well-known brands were selected (Becker-Olsen et al., 2006; Lafferty et al., 2004; Samu & Wymer, 2009). Eight brand names from each product category were identified. A total of 47 undergraduate students were asked to rate their familiarity (1=not at all familiar/7=very familiar) and perceived quality (1=poor quality/7=good quality) on the candidate brands using seven-point scales. Four brands well-known brands in Spain were selected: Pascual for milk (F=6.09; Q=6.19); Nestlé for chocolates (F=6.47; Q=6.23); HP for printers (F=6.36; Q=6.45); and Sony for Mp3 players (F=6.55; Q=6.55).

Finally, another pretest was conducted to select CRM campaigns promoted by the causes previously selected (i.e. Red Cross and Greenpeace) that would represent a different level of perceived fit between the products and the causes. Perceived fit in this pretest was manipulated by providing different scenarios (e.g. 3% of the product purchase price will be donated to the Red Cross campaign for food distribution in Africa; 3% of the product purchase price will be donated to the Greenpeace campaign for preventing climate change). Then, a group of undergraduate students (n=46) were asked to rate the degree of perceived fit of the product categories selected and the causes on seven-point scales (1=complementary/7=not complementary and 1=makes sense/7=does not make sense). The results showed a high perceived fit in the following scenarios: milk and Red Cross; chocolates and Red Cross; printer and Greenpeace; and Mp3 players and Greenpeace (see Table 1).

Pretest 3 results (fit levels).

| Product (Brand) | High fit cause (mean) | Low fit cause (mean) | Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk (Pascual) | Red Cross (6.00) | Greenpeace (2.02) | 5.448*** |

| Chocolates (Nestlé) | Red Cross (4.98) | Greenpeace (1.67) | 5.498*** |

| Printer (HP) | Greenpeace (4.48) | Red Cross (2.23) | 5.448*** |

| Mp3 (Sony) | Greenpeace (4.38) | Red Cross (2.11) | 4.857*** |

A total of 186 undergraduate business students enrolled at a major university in Spain participated in the study. The research used a survey-based experiment with eight different scenarios. The subjects were randomly assigned to one of these experimental conditions. The use of student samples is very common in CRM research (e.g. Ellen et al., 2006; Lafferty, 2007; Lafferty & Goldsmith, 2005; Lafferty et al., 2004; Lii & Lee, 2012; Moosmayer & Fuljahn, 2010; Nan & Heo, 2007). In addition, homogeneous samples, such as students, facilitate the control of extraneous variables that could potentially confound the results (Callow & Lerman, 2003; Kwok & Uncles, 2005).

Similar to previous research, fictitious campaigns were created (Lii & Lee, 2012). These campaigns featured offers from Nestlé, Pascual, HP and Sony to donate, in return for a purchase of one of their products (chocolates, milk, printers and Mp3 players, respectively), a percentage of the purchase price (3%) to help one of the following campaigns: the Red Cross campaign for food distribution in Africa, or the Greenpeace campaign for preventing climate change.

Eight different questionnaires, with analogous questions, were used to collect the data. The questionnaires had two parts. The first part included questions related to the hedonic (vs. utilitarian) nature of the product and brand's perceived quality, among other issues. Next, subjects were provided with one of the eight scenarios (e.g. in scenario 1 participants were told that Nestlé (chocolates) was supporting the Red Cross campaign). They were then asked to assess the perceived fit between the product and the cause, the credibility of the campaign, the brand attitude and their purchase intentions.

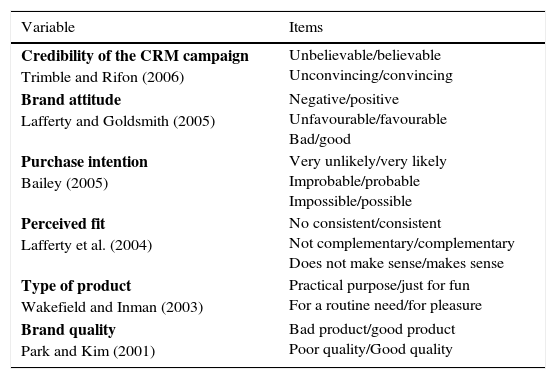

MeasuresWell-established scales were employed to measure the constructs in this study. In all cases except for the hedonic vs. utilitarian nature of the product, eleven-point scales were used. Table 2 provides an overview of all the measures.

Measurements.

| Variable | Items |

|---|---|

| Credibility of the CRM campaign Trimble and Rifon (2006) | Unbelievable/believable Unconvincing/convincing |

| Brand attitude Lafferty and Goldsmith (2005) | Negative/positive Unfavourable/favourable Bad/good |

| Purchase intention Bailey (2005) | Very unlikely/very likely Improbable/probable Impossible/possible |

| Perceived fit Lafferty et al. (2004) | No consistent/consistent Not complementary/complementary Does not make sense/makes sense |

| Type of product Wakefield and Inman (2003) | Practical purpose/just for fun For a routine need/for pleasure |

| Brand quality Park and Kim (2001) | Bad product/good product Poor quality/Good quality |

Three dependent variables associated with consumer responses to CRM were measured. Credibility of the CRM campaign was assessed based on two eleven-point bipolar scale items, following Trimble and Rifon (2006). Attitude towards the brand was measured using three eleven-point bipolar scale items, based on Lafferty and Goldsmith (2005). Finally, purchase intention was measured with three 11-point bipolar scale items, as suggested by Bailey (2005). All three scales demonstrated unidimensionality, with one factor accounting for 96.21%, 86.37% and 75.08% respectively. Credibility exhibited a high degree of reliability (α=.96), as did attitude towards the brand (α=.92) and purchase intention (α=.83). Therefore, to test the hypotheses, the mean scores of the corresponding items on each scale were averaged.

Measures of perceived fit were adapted from Lafferty et al. (2004). The hedonic vs. utilitarian nature of the product was measured with two dichotomous scales (practical purpose/just for fun; for a routine need/for pleasure) based on Wakefield and Inman (2003). Perceived brand quality, which was included in the analysis as a covariate, was assessed using a subset of two items from Park and Kim (2001). Principal components analyses with varimax rotation were performed to evaluate the dimensionality of the scales. The results suggested that the corresponding items of each scale could be grouped into a single factor with significant factor loadings, and the explained variance exceeded 60% in each case. Scale reliabilities were assessed using Cronbach's alpha. All the scales exhibited a high degree of reliability.

FindingsManipulation checksManipulation checks were carried out to determine whether treatments related to the nature of the product and the perceived fit were effective. As explained above, the hedonic vs. utilitarian nature of the product was measured with dichotomous scales (practical purpose/just for fun; for a routine need/for pleasure). The results show that the chocolates and Mp3 players were mainly considered hedonic by respondents (chocolates=88.05%, Mp3 player=77.5%), while milk and printers were mainly considered utilitarian (milk=92.7%, printer=95.55%). Perceived fit manipulation was also successful. Within the chocolates and milk product categories, perceived fit (PF) with the Red Cross was significantly higher than with Greenpeace (PFChocolates-RedCross=5.80, PFChocolates-Greenpeace=3.69, t=4.513, p<0.01; PFMilk-RedCross=7.33, PFMilk-Greenpeace=4.75, t=4.551, p<0.01). In contrast, within the Mp3 players and the printers, perceived fit with Greenpeace was significantly higher than with the Red Cross (PFMp3-RedCross=2.78, PFMp3-Greenpeace=5.07, t=−3.625, p<0.01; PFPrinter-RedCross=3.33, PFPrinter-Greenpeace=5.38, t=−4.417, p<0.01).

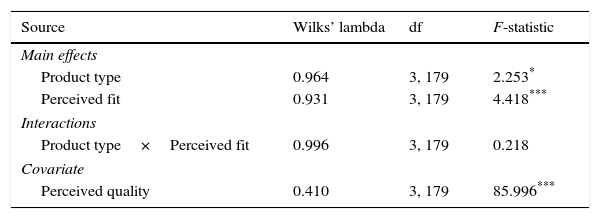

Test of hypothesesTo test the hypotheses, a MANCOVA was conducted with the nature of the product and perceived fit as independent variables. The cognitive, affective and behavioural responses were included in the analysis as dependent variables. Previous studies indicate that a brand's perceived quality might affect the CRM results (e.g. Park & Kim, 2001; Tsai, 2009). Thus, this variable was entered as a covariate. Table 3 presents the MANCOVA results for the dependent variables.

These results reveal a significant main effect of both the nature of the product and the perceived fit. These effects are further investigated using univariate analyses. Table 4 summarizes the univariate ANCOVA results.

Univariate ANCOVA results.

| Source | Credibility F-statistic | Brand attitude F-statistic | Purchase intention F-statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | |||

| Product type | 1.539 | 4.900** | 3.491* |

| Perceived fit | 5.860** | 9.087*** | 1.28 |

| Interactions | |||

| Product type×Perceived fit | 0.226 | 0.151 | 0.273 |

| Covariate | |||

| Perceived quality | 11.536*** | 259.685*** | 22.823*** |

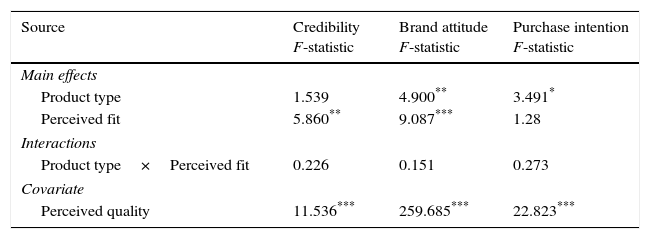

H1a, H1b and H1c proposed that CRM initiatives linked to hedonic products (vs. utilitarian) would lead to higher credibility, a more positive attitude towards the brand, and a higher purchase intention. As can be seen in Table IV, the univariate test results show significant effects of product type on the attitude towards the brand (F=4.900, p<0.01) and purchase intention (F=3.491, p<0.10). Hedonic products have higher estimates of brand attitude (M=7.27) than utilitarian products (M=7.25). In contrast, purchase intention was higher in utilitarian products (M=6.11) than hedonic products (M=5.79). Thus, the results only support H1b.

H2a, H2b and H2c proposed that CRM initiatives with a high perceived fit between the brand and the cause would lead to higher credibility, a more positive attitude towards the brand, and a higher purchase intention. The univariate test results (see Table 4) show significant effects of perceived fit on credibility (F=5.860, p<0.05) and the attitude towards the brand (F=9.087, p<0.01). The mean for credibility for the high fit condition (M=6.05) was higher than in the low fit condition (M=5.38). Similarly, brand attitude was higher when there was a high fit between the product and the cause (M=7.5) than when the fit was low (M=7.03). Thus, the results suggest that the higher the fit between the product and the cause, the more favourable the credibility of the campaign and the brand attitude. These results support hypotheses H2a and H2b. In contrast, there was no main effect of fit on purchase intention (F=1.28, p>0.1). Therefore, H2c was not supported.

Finally, the analysis revealed a significant effect of the perceived brand quality, included as a covariate, on the credibility of the campaign, the brand attitude and purchase intentions.

Discussion and managerial implicationsGiven the fact that companies are operating under increasing competition, they need to differentiate, reach new customers, enhance their corporate image and generate incremental sales. In addition, they need to engage in socially responsible behaviours. In this context, CRM is seen as a way for companies to achieve both corporate and nonprofit objectives (Samu & Wymer, 2009). Consumers’ responses to CRM practices are complex. Therefore, this paper analyzes the influence of two determinants that may condition the success of a CRM campaign: the product type and the perceived fit between the product and the cause.

Trying to solve the ambiguity identifying in former studies we have adopted the proposal made by authors such as Lafferty et al. (2004) and Currás-Pérez et al. (2012). Our results must be considered under the functional fit. Our data revealed that product type had a significant main effect on the consumer response variables included in the analyses. Specifically, the findings showed that the utilitarian or hedonic character of the product used in the CRM campaign influences both brand attitude and purchase intention. As proposed in previous research, attitude towards the brand was greater for the hedonic products than for the utilitarian ones. In contrast, despite the fact that some studies have suggested that CRM used in hedonic products should enhance purchase intention, this was not the case in this study. Previous literature suggests that the feeling of guilt evoked by the purchase of hedonic products can be tempered when the hedonic purchase is linked to a cause (Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). However, in our study, contrary to what was expected, CRM linked to utilitarian (vs. hedonic) products lead to higher purchase intention. This finding is consistent with other recent studies (Roy, 2010; Subrahmanyan, 2004). The experiential benefits generated by the cause may explain this finding. CRM campaigns generate emotional arousal and affective benefits. The addition of these benefits to the expected functional benefits of the utilitarian products may enhance their overall perceived value (Lim & Ang, 2008) and, consequently, their purchase intentions. Further, the consumption of utilitarian products is typically rational, cognitively driven and goal oriented (Roy & Ng, 2012). These characteristics may make consumers more aware of the need to help causes, thereby increasing their purchase intentions.

Likewise, perceived fit between the product and the cause seems to play a key role. Perceived fit had a significant effect on both the credibility of the campaign and the attitude towards the brand. In contrast, a high level of fit did not have any significant effect on purchase intention. Extant literature has widely discussed the influence of the perceived fit between the product and the cause on consumer response. Although most researchers advocate a high product-cause fit level, others call for a moderate or low level of fit (Drumwright, 1996). Several researchers have not supported that higher levels of fit can improve consumer responses to CRM campaigns (e.g. Lafferty, 2007; Nan & Heo, 2007). Our results show that fit has a significant effect on both the cognitive and affective level of the consumer response. When consumers perceive a high fit, the campaign is more credible. In addition, the beliefs and affect associated with the cause might be transferred to the brand, thus improving consumers’ perceptions towards it. The findings in this study suggest that perceived fit between the product and the cause, in contrast, does not play a key role in terms of influencing the behavioural level of the consumer response. As Lafferty (2007) explains, other variables, such as the congruence among the individuals and the firm, can influence the purchase intent. Therefore, two CRM campaigns with different levels of fit could get similar effects.

The research findings have several managerial implications. Our findings related to the effects of type of product on consumer responses were intriguing. The cognitive response was not affected by this factor. Therefore, the nature of the product does not appear to be a relevant determinant of the credibility of the campaign. In contrast, while the affective response, measured through the brand attitude, was higher for hedonic products, the behavioural response, measured through purchase intentions, was slightly higher for utilitarian products. These mixed results could suggest that CRM campaigns are not only suitable for hedonic products, as has usually been proposed in the literature, but also for utilitarian products. Indeed, our findings show that linking a CRM campaign to a utilitarian product may be more effective in influencing purchase intentions. Therefore, marketers selling hedonic products can benefit from a more favourable attitude towards their brands, whereas marketers selling utilitarian products can benefit from higher purchase intentions.

Our findings also provide some insights into the mixed results about the influence of the perceived fit between the product and the cause. A high level of fit did not have any significant effect on purchase intention. It is interesting to note, however, that according to the results of our study, a CRM campaign with high product-cause fit, compared with one of low fit, is more effective in influencing the credibility of the campaign and the attitude towards the brand. Therefore, the perceived fit between the cause and the product does appear to be relevant. As such, marketing managers should acknowledge the importance of linking their products with congruent causes. Some consumers are sceptical about the firms’ objectives when using CRM alliances. Therefore, higher fit can reduce this scepticism and increase the credibility of the campaign. Similarly, as most managers seek to maintain and reinforce positive attitude towards their brands, linking their brands to CRM initiatives appears to be a wise alternative to reach this objective and build consumer-based brand equity. The selection of the cause is, therefore, extremely important when designing these initiatives.

Limitations and further researchAs with all research, this study is subject to several limitations. First, a convenience sample was used. Future research should be conducted using different groups of consumers to generalize the results of this study to other populations. Second, the products, brands and causes used as stimuli in the experiment could have impacted the research findings. We recommend that further research consider other product categories, brands and causes.

Our results also suggest that the interaction effect between fit and product type is not significant on credibility, attitude and purchase intention. However, although this was not the objective of this research, we believe that further analysis in the interaction effects would be of interest and it represents one of our proposals for future research.

Finally, this study has focused on the role of product type and perceived fit. More specifically, the core objective has been functional fit (product category) rather than brand fit (image). As potential differences may arise when functional and brand fits are analyses, studies where simultaneous analyses are performed would be of great interest. We also advocate future research to analyze additional factors, such as variables related to the cause, the non-profit organization or the consumer characteristics, in order to gain a better understanding of consumers’ responses to CRM initiatives.

Nevertheless, this study offers some new insights and adds to the literature on consumer responses to CRM. Further, it is hoped that the findings presented in this research will help managers to improve the effectiveness of this practice.

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the following sources: I +D+ i (ECO2014-54760) from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation; Generés research project (S09) from the European Social Fund and Gobierno de Aragón; and from the programme “Ayudas a la Investigación en Ciencias Sociales, Fundación Ramón Areces”.