This paper proposes a model in order to analyze whether standardized management systems facilitate the implementation and integration of CSR within the technology company, studying which is the influence of CSR in reputation and improvement of these companies and whether it has a positive impact on the economic performance of the company. The study was conducted in companies located in Spanish Science and Technology Parks. On the one hand, model results shows that there is a positive, direct and statistically significant relationship between the integration of CSR and reputation; on the other hand, performance and internal improvement has also this relationship. Likewise, the model shows also some indirect relations between management system before the implementation of CSR and reputation and internal improvement.

The modern definition of quality extends beyond products/services specifications to encompass the requirements of a variety of stakeholders (Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2011b). Stakeholder requirements vary from ensuring employees’ health and safety, sustainability, customer satisfaction, and transparency in organizational affairs to execution of business processes in a socially responsible manner (Turyakira, Venter, & Smith, 2014). To meet stakeholder requirements in a systematic manner, organizations use certain management systems standard (MSs) such as quality, environment, health and safety, and social accountability (Asif, Fisscher, Bruijn, & Pagell, 2010).

Such systems are standardized, because standardization is not only a coordinating mechanism but also an instrument of regulation comparable to other instruments such as markets, public regulation or hierarchies or formal organizations. Without standardization trade is extremely difficult in the global economy (Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2011a).

Quality management standards (QMS) and environmental management standards (EMS), are both the most successful have obtained in recent years compared with others (Llach, Marimon, & Alonso-Almeida, 2015). Thereby, between 2006 and 2014, the number of certifications has increased by 241,250 for ISO 9001 and 195,937 ISO 14001. At the end of 2014, ISO 9001 accounted for 1,138,155 registered companies in more than 188 countries and ISO 14001 for 324,148 in about 170 countries (ISO, 2014). In contrast, in June 2012, 3083 certified facilities were reported by Social Accountability International (Llach et al., 2015). These data warn us that in absolute terms in 2014 certification ISO 9001 is 3.5 times higher than certification ISO 14001.

In addition to ISO 9001 and ISO 14001, the proliferation of other MSs such as occupational safety and health (OHSAS 18001 and CSA Z1000), social responsibility (SA 8000 and AA 1000), information security (ISO 27001), supply chain security (ISO 28001), and energy (ISO 50001) (Gianni & Gotzamani, 2015), offers the possibility to companies to integrate their management in a single system to somehow benefit from synergies created between the systems to be integrated (Simon, Bernardo, Karapetrovic, & Casadesús, 2011; Simon, Karapetrovic, & Casadesus, 2012).

In a context where, MSs appear frequently into management and company policies more and more organizations are applying not only one, but a range of MSs to satisfy their own needs as well as those of external stakeholders (Simon et al., 2012).

Moreover, organizations are adapting to changes in the economy constantly, and those that adapt best have the greatest possibilities to survive in the market. A key factor for their success is innovation, which is critical to sustain customer satisfaction, reducing costs, and enhancing competitiveness in the long term (Bernardo, 2014). Innovation is usually defined by including products and services, and management processes, so the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is in itself an innovation for companies management of. In fact, CSR practices tend to create innovation products or process seeking for a better quality (Benito Hernández & Esteban Sánchez, 2012).

Hence, companies should adopt formalized CSR practices and establish the procedures and tools that are aligned with corporate strategy (Bocquet, Le Bas, Mothe, & Poussing, 2013). Several studies claim that CSR has a significant positive contribution to competitiveness (Battaglia, Testa, Bianchi, Iraldo, & Frey, 2014; Boulouta & Pitelis, 2014). In this way, the European Union states that “A strategic approach to CSR is increasingly important to the competitiveness of enterprises. It can bring benefits in terms of risk management, cost savings, access to capital, customer relationships, human resource management, and innovation capacity” (Communication from the European Commission, 2011, pag.3).

There are three remarkable ways established in the scientific literature through which CSR helps and encourages innovation (Benito Hernández & Esteban Sánchez, 2012): (1) innovation resulting from dialog with various stakeholders both internal and external to the company, (2) identifying new business opportunities arising from social and environmental demands on products and more efficient processes or new forms of business and (3) creating better places and ways of working that encourage innovation and creativity, such as those based on more employee participation and confidence in them (Benito Hernández & Esteban Sánchez, 2012).

The main reasons for innovating are to (1) improve the current situation (achieved by, for example, reducing costs, raising margins and providing stability for the workforce), (2) open new horizons (by, for example, repositioning perceptions of an organization and gaining a competitive advantage), (3) reinforce compliance (by complying with legislation and fulfilling social and environmental responsibilities), and (4) enhance the organization's profile (by attracting extra funding and potential alliance partners for example) (Bernardo, 2014).

If CSR is integrated into business processes, it creates innovative practices in them (Benito Hernández & Esteban Sánchez, 2012) and therefore, a improvement into organization. This internal improvement can be understood as an improvement in operating efficiency and control through training and employee participation (Benito Hernández & Esteban Sánchez, 2012).

Furthermore, this improvement entails an exploitation of synergies and benefits arising from the integration of different management systems (Bernardo, 2014; Bernardo, Simon, Tarí, & Molina-Azorín, 2015; Gianni & Gotzamani, 2015). So far, integration is proven beneficial to the internal cohesion, the use and performance of the systems, the corporate culture, image and strategy and the stakeholders’ implication (Gianni & Gotzamani, 2015).

For all these reasons above, the aims of this paper are: (1) analyzing whether standardized management systems facilitate the implementation and integration of CSR within the technology company, (2) studying which is the influence of CSR in reputation and improvement of these companies and (3) if it has a positive impact on the economic performance of the company, as some authors suggest (e.g. Gallardo-Vázquez & Sanchez-Hernandez, 2014).

For theses aims the work is divided into four sections. First, theoretical and empirical contributions related to the relationships between the variables that are included in the research model are reviewed. Second, methodology employed to test the model is described. Third, results are presented, ending with conclusions and discussion of the results obtained. This final section also highlights the main implications for future research.

Research background and hypothesesIt will conduct a review of the literature analyzing (1) integrated management systems, (2) the integration of CSR in technology companies, (3) Implementation of measures in technology companies CSR and (4) Performance in technology companies in order to propose research hypotheses.

Management systemsIn the study of individual management systems there is abundant literature. For example, the literature on environmental management has studied the conditions of companies that decide to implement ISO14001 system, its certification and subsequent its economic impact (Cañón de Francia & Garcés Ayerbe, 2006; Marimon, Llach, & Bernardo, 2011; Narasimhan & Schoenherr, 2012). The focus on safety and occupational health management systems has studied the relationship of this system with reduced risks to workers, the reduction of accidents and the firm performance (Duijm, Fiévez, Gerbec, Hauptmanns, & Konstandinidou, 2008; Fernández-Muñiz, Montes-Peón, & Vázquez-Ordás, 2009; Fernández-Muñiz, Montes-Peón, & Vázquez-Ordás, 2012; Fernández-Muñiz, Montes-Peón, & Vázquez-Ordás, 2012b; Veltri et al., 2013; Vinodkumar & Bhasi, 2011).

Comparative studies between pairs of standards also appear in literature. Especially regarding quality (QMS) and environment (EMS) (Albuquerque, Bronnenberg, & Corbett, 2007; Casadesús, Marimon, & Heras, 2008; Delmas & Montiel, 2008; Marimon, Heras, & Casadesus, 2009) that analyze the relationship between them and their commonalities.

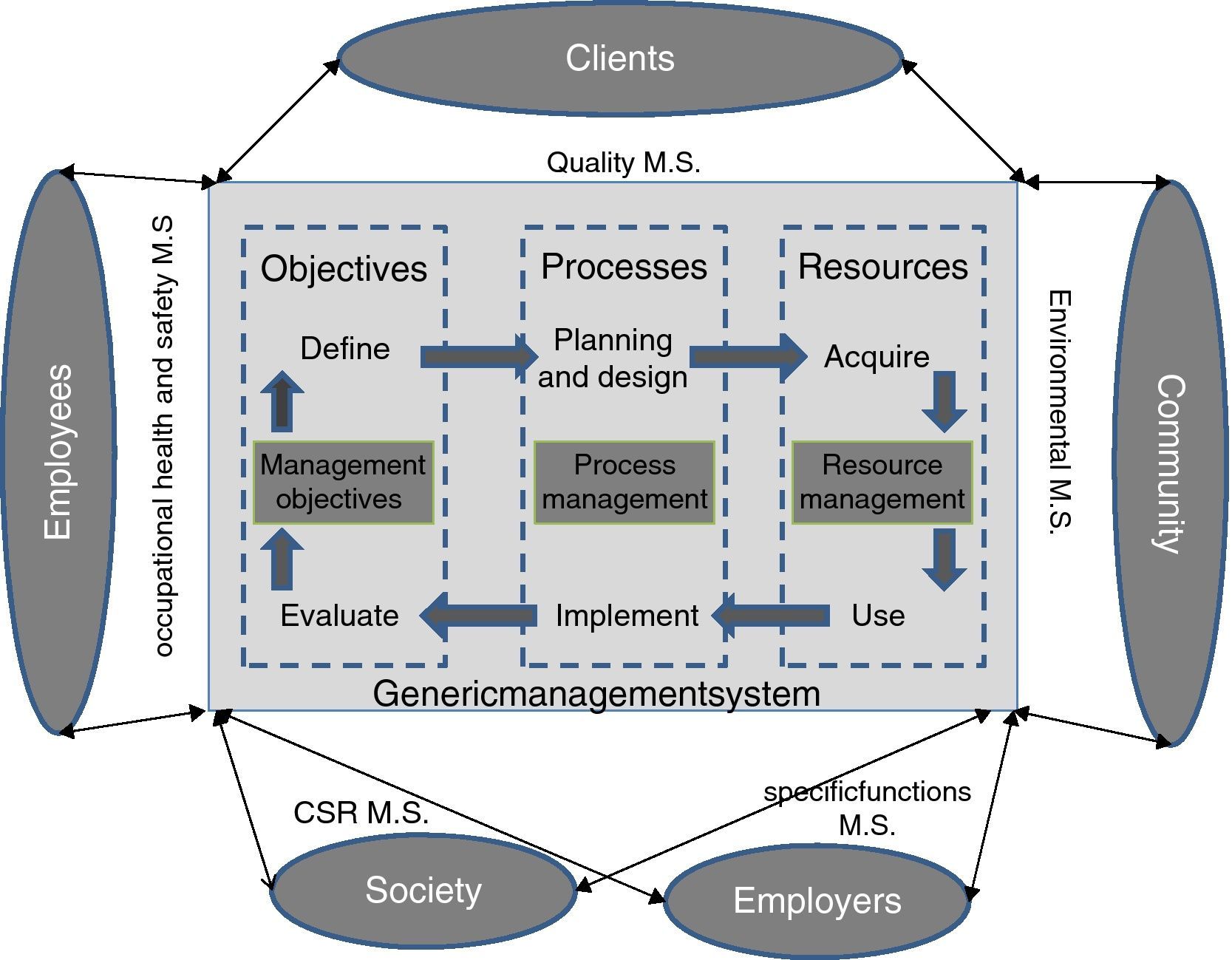

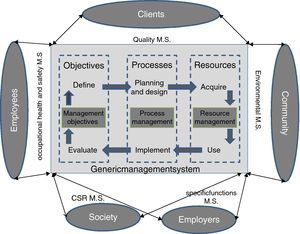

The first model of integration based on a systemic approach was developed by Karapetrovic and Willborn (1998) including the management systems ISO 9001: 1994 and ISO 14001: 1996. These authors introduced the concept of “system of systems” which had a nucleus containing the common requirements to integrate management systems (IMS).

This model was updated later by Karapetrovic and with Jonker adding two new systems, (1) the system of occupational health and safety, based on the OHSAS 18001: 1998 and (2) the system of social responsibility based on the model SA 8000 (Karapetrovic & Jonker, 2003). The figure below shows the model of “system of systems” that rise to the concept of integrated system.

In Fig. 1 we can observe a central core management system sharing different requirements while specific ones are located in parallel functional modules resulting a new system, thus constituting an integrated management system in which the components are interrelated but without sacrificing their individual identity and without invading other management systems.

Systems integration proposed by Karapetrovic and Jonker (2003).

Therefore, in many companies, quality, health and safety and environmental management exist as three parallel systems (Hamidi, Omidvari, & Meftahi, 2012). Hence, an integrated management system (IMS) must contemplate aspects: (1) focusing specifically on the quality, health and safety, environment, human resource and finance, and (2) generally stakeholders and accountability to these stakeholders, thus assuming different levels of integration (Jørgensen, Remmen, & Mellado, 2006).

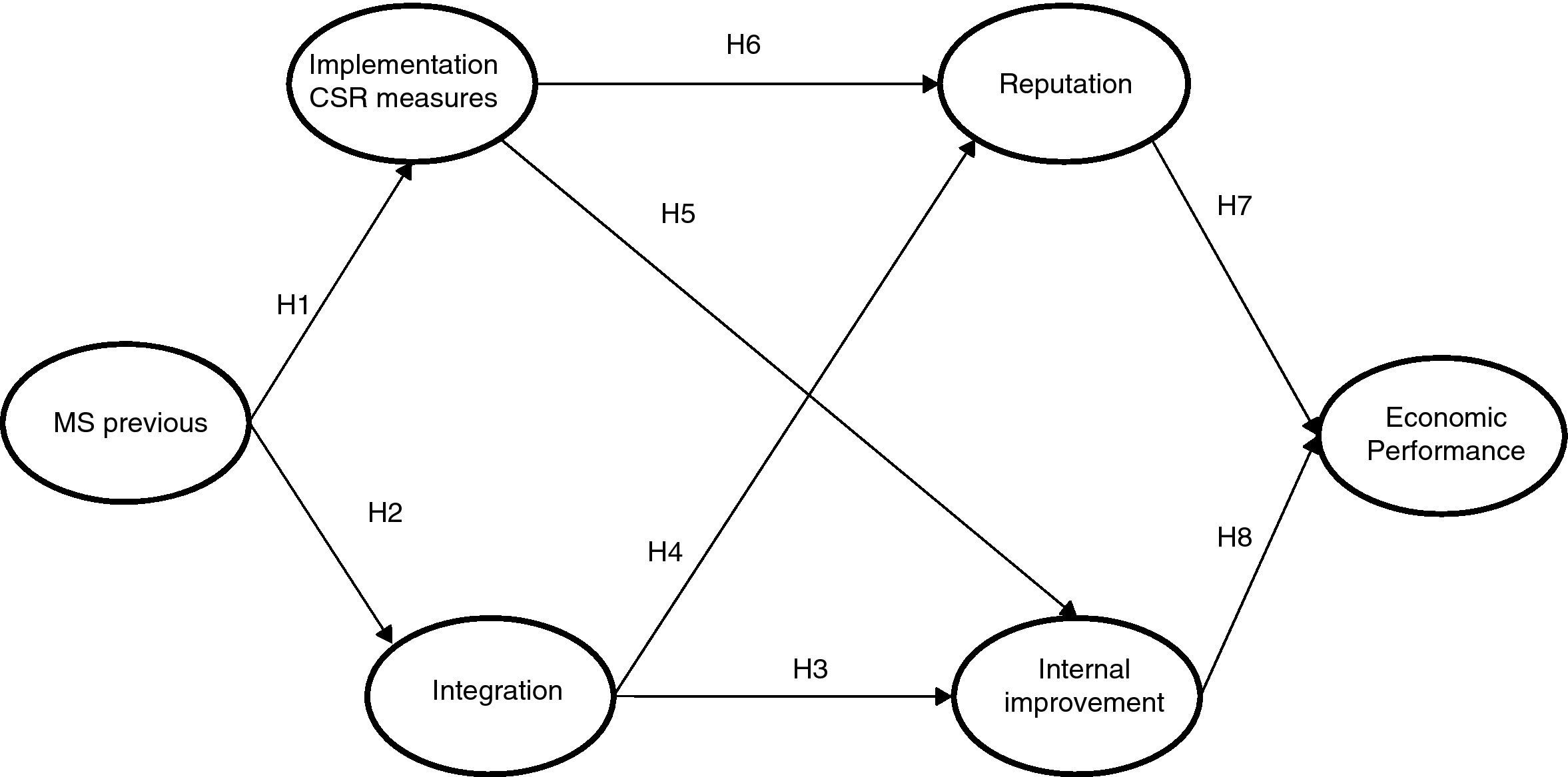

Therefore, and after review in reference to management systems integration, the first research hypothesis is proposed in the following terms:H1

The existence of previous standardized management systems has a positive effect on implementation of CSR measures.

The integration of MSs has been analyzed from a theoretical and practical point of view as such claim Bernardo, Casadesus, Karapetrovic, and Heras (2009). On the one hand we have several theoretical studies (e.g. Asif et al., 2010; Ciobanu, 2010; Rocha Romero, 2006; Simon et al., 2011, 2012) which explain us the followed strategies, methodologies, levels and benefits of integration. On the other hand, we have different empirical studies that complement the above (e.g. Bernardo et al., 2009; Bernardo, Casadesus, Karapetrovic, & Heras, 2010; Bernardo, Casadesus, Karapetrovic, & Heras, 2012a; Karapetrovic & Casadesús, 2009; Lindgreen, Swaen, & Johnston, 2009; Santos, Mendes, & Barbosa, 2011; Zeng, Xie, Tam, & Shen, 2011).

The need for the integration of individual MSs is rooted in the need to effectively utilize organizational resources (Asif, Searcy, Zutshi, & Fisscher, 2013).

Thus, the integration of operations, quality, strategy and technology is increasingly seen as a way to maintain the competitive advantage of organizations, as well as a way to overcome the disappointments with programs and quality standards (Castka & Balzarova, 2007).

Therefore, the integration of MSs can be defined as putting together different function-specific management systems into a single and more effective IMS (Bernardo et al., 2015) in order to achieve a continuous improvement and satisfaction of stakeholders (Bernardo et al., 2009) and its integration into business strategy.

In regard to the integration of systems management, methodology and case studies exist in literature in order to help any organization to carry out the integration process (Simon et al., 2012) and follow different integration strategies. Integration strategy refers to the scope and the sequence of MSs standards’ adoption. Four options of implementation sequence are identified: first QMS, then others; first EMS, then others; QMS and EMS simultaneously, then others; and a common IMS core, then IMS modules (Gianni & Gotzamani, 2015).

Hence, this integration falls mainly on ISO9001, ISO 14001 and OHSAS 18001 standards, namely the integration of systems quality, environmental and occupational health and safety, dominated by the first two standards (Bernardo, Casadesus, Karapetrovic, & Heras, 2012b; Casadesús, Karapetrovic, & Heras, 2011).

Nevertheless, the integration of CSR can be facilitated by standardized management processes previously implanted as claimed several authors (Asif et al., 2013; Vilanova, Lozano, & Arenas, 2009). Thus, the second hypothesis is proposed as follows:H2

The existence of previous standardized management systems positively influences the integration of CSR in the management system of the organization.

Furthermore, integration can be partial or total focused on aspects such as goals and objectives, system documentation and procedures (Sampaio, Saraiva, & Domingues, 2012). For example, Bernardo et al. (2009), claim that organizations follow a pattern with respect to documentation and procedures that make up the majority and it seems clear that start with strategic objectives, better documentation and procedures, leaving the integration of operations and tactics later. However, the role of the people involved in integrated management systems is not significant, contrary to what is stated in the theoretical literature and in the standards of application.

Integrating CSR in technology companiesThe integration of these systems with CSR is recent interest in academia (Asif et al., 2013; Asif, Searcy, Zutshi, & Ahmad, 2011) and infrequent. In fact, in a study by Bernardo et al. (2012b) notes that of 422 Spanish companies studied, only 26 have the social responsibility system fully integrated with other systems (6.16% of total); 11 companies have it partially integrated (2.60% of total); 5 have a CSR system but is not integrated with any other (1.18% of total), that is only 8.76% of the companies surveyed have the CSR system fully or partially integrated with other systems. Moreover, most literature refers to this integration is based on standards such as SA 8000 (Asif et al., 2010; Jørgensen et al., 2006; Karapetrovic & Jonker, 2003; Llach et al., 2015). Despite during the past three decades, CSR standards have increased in number and popularity. Likewise, there are more than 300 global corporate standards, each with its own history and criteria which addresses various aspects of corporate behavior and responsibility (for example, working conditions, human rights, environmental protection, transparency, bribery) (Koerber, 2009; Marimon, Alonso-Almeida, Rodríguez, & Cortez Alejandro, 2012).

The guidelines ISO 26000 was published in September 2010 (Merlin, Duarte do Valle Pereira, & Pacheco Junior, 2012) and represents a major step forward. The guidance provided in this standard can allow any organization to achieve a truly integrated management system (Pojasek, 2011).

Experts from 99 ISO member nations and 42 public and private sector organizations were developing the standard in order to provide agreement about definitions, core subjects and integration processes of social responsibility in organizations (Gilbert, Rasche, & Waddock, 2011).

This standard provides guidance on: the principles of social responsibility, recognition of social responsibility and participation of stakeholders in seven key aspects and social responsibility issues and how to integrate socially responsible behavior into the organization (Merlin et al., 2012).H3

The integration of CSR has a positive influence on the internal improvement of the technology company.

The guidance provided in this standard, as Pojasek (2011) states, allows an organization to achieve a system of sustainability management, and hence of its social responsibility, truly integrated. So, ISO 26000 defines Social Responsibility as “The responsibility of an organization for the impacts of its decisions and activities on society and the environment through transparent and ethical behavior that contributes to sustainable development, including health and the welfare of society; takes into account the expectations of stakeholders; is in compliance with applicable law and consistent with international norms of behavior; and is integrated throughout the organization and practiced in its relationships” (AENOR, 2012; Caballero-Díaz, Simonet, & Valcárcel, 2013).

ISO 26000 can be perceived as an evolutionary step in standard innovation (Hahn, 2012). In fact, ISO 26000 is in a strategic plan of the organization through which to develop a tactical plan in the different management systems (Merlin et al., 2012), so at a time, as highlighted above, it must be integrated throughout the organization.

It is therefore, we do not limit ourselves only to “traditionally” management systems standard but we also include in our study the integration of aspects of CSR based on ISO 26000 for the implementation of CSR in which the human factor takes highly relevant to the internal and continuous improvement of the organization.H4

The integration of CSR has a positive influence on improving the external perception (reputation) of the technology company.

Therefore one aspect to consider is the internal improvement and reputation of the organization through the integration of systems and the involvement of staff and their effects on the performance of the company because the performance of a IMS is a emerging research topic, as assert Gianni and Gotzamani (2015).

Implementation of CSR measures in technology companiesMany studies on CSR can be founded in scientific literature. Both large companies (Melé, Debeljuh, & Arruda, 2006), and small (Baumann-Pauly, Wickert, Spence, & Scherer, 2013; Vázquez-Carrasco & López-Pérez, 2013). In different sectors (Alcaraz & Rodenas, 2013; Bernal Conesa, De Nieves Nieto, & Briones Peñalver, 2014; Moseñe, Burritt, Sanagustín, Moneva, & Tingey-Holyoak, 2013; Pérez Ruiz & Rodríguez del Bosque, 2012); and even one that refers to technology companies (Guadamillas-Gómez, Donate-Manzanares, & Skerlavaj, 2010).

Therefore, it is considered limited information in the technology sector, denoting that have not been analyzed in depth the influences of a strategy based on CSR and its integration into the management of the company, so it is estimated interesting further study of it in Spanish technology companies since previous research has shown that organizations with a strategic focus on innovation are committed to improve their internal organizational capacities to become more competitive in a global environment (Suñe, Bravo, Mundet, & Herrera, 2012).

Several authors (Perrini, Russo, & Tencati, 2007; Spence, 2007) have noted the sector as one of the elements affecting the organizational culture in adopting and integrating CSR practices in the strategic plans of the organizations. For example, Perrini et al. (2007) found that companies in sector of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) were more likely to monitor and report on their behavior CSR while manufacturing firms were more interested in motivating employees through volunteer activities in the community.H5

The implementation of CSR activities has a positive influence on the internal improvement of the organization.

In a study carried out by Lorenzo, Sánchez, and Álvarez (2009) states that the fact of belonging to technology and telecommunications sectors have a positive but not significant effect in the dissemination of CSR actions.

In certain technological sectors, product development periods are extremely long and businesses often have negative results in their first years of life, put forward higher financing difficulties. In these cases, financial indicators are not effective in assessing the business potential, being more suitable for intangible assets and knowledge-based (Quintana García, Benavides Velasco, & Guzmán Parra, 2013).

In these intangible assets we can find CSR which can enhance reputation of the company with banks and investors and facilitate their funding (Benito Hernández & Esteban Sánchez, 2012; Cheng, Ioannou, & Serafeim, 2014).H6

The implementation of CSR measures has a positive influence on improving the reputation of the organization.

Performance in technology companiesFollowing the previous literature review is to investigate the knowledge and implementation of CSR in the Spanish Technology Industry since the activity of technology and information technology companies have a high relevant social impact (Luna Sotorrío & Fernández Sánchez, 2010), its relationship with other management systems of the company, the integration of such systems and whether such integration facilitates the adoption of strategies in the context of CSR, and the impact of CSR on economic performance since CSR practices can improve the reputation of the company with banks, investors and also facilitate their funding (as we saw in the previous section) and thus positively influence the performance of the company.

The implementation of CSR in organizations, as some studies have shown, has a positive relationship with the financial benefits, and specifically technology industries, can increase their economic performance by CSR (Chang, 2009).

Although, there is no clear consensus in the debate on measures of CSR and economic performance (Ramos, Manzanares, & Gómez, 2014) many researches suggests that there should be a positive relationship between the two variables (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sanchez-Hernandez, 2014; Garcia-Castro, Ariño, & Canela, 2009). There are also studies that suggest otherwise (Muñoz, Pablo, & Peña, 2015) but there are few studies examining the relationship between CSR technology companies, and its performance (Wang, Chen, Yu, & Hsiao, 2015).H7

Improving reputation has a positive influence on economic performance of the technology company.

Moreover, studying the role of technology companies in environmental management, sustainability and CSR is still in its early stages (Wang, Chen, & Benitez-Amado, 2015). For this reason it is to investigate and analyze the situation of the Spanish technology companies face to CSR, taking as a starting point the Spanish Science and Technology Parks.

Nowadays, there are 67 Spanish Science and Technology Parks. They host to firms with different interests: academic spin-offs, Technology-based firms and start-ups (Jimenez-Zarco, Cerdan-Chiscano, & Torrent-Sellens, 2013). But all are characterized by a strategic orientation toward innovation, knowledge creation, technological development and cooperation (Vásquez-Urriago, Barge-Gil, Rico, & Paraskevopoulou, 2014) to increase their organizational capacity in order to improve internally.

Technology Parks have in common not only the creation of technology companies but also they attract companies already established to promote regional development through a technological approach and the creation of employment and welfare (Jimenez-Zarco et al., 2013; Ratinho & Henriques, 2010).

Therefore technology parks would be directly related to two of three dimensions of CSR (social and economic) and generate a network of cooperation between technology firms. These firms, can increase the capacity to generate knowledge and positively expand relationships with their own business agents. If we also add the adoption of CSR policies, it will allow greater flexibility and opportunities to address social problems with innovative products or services, increasing the ability to attract, retaining and motivating staff and accessing to new knowledge and information, so that companies could increase their economic performance and competitiveness (Benito Hernández & Esteban Sánchez, 2012; Vásquez-Urriago et al., 2014).H8

Internal organizational improvement has a positive influence on economic performance of the technology company.

The objectives of the research are summarized in studying the influence of the system prior to the implementation of CSR management and if that can help positively influence the implementation and integration of CSR in the IMS. The influence of CSR on reputation technology companies, internal improvement and the performance. Therefore, and after review of the literature and the approach of the hypotheses, the following conceptual model shown in Fig. 2 was made.

MethodologyThere are a great variety of methods for aggregating data in Social Sciences (Rodríguez Gutiérrez, Fuentes García, & Sánchez Cañizares, 2013) but they are not applied generally in the field of CSR research. One of the most widely used methods is the factor analysis, based mainly in works which study is based on surveys. In the last years there have been studies that in addition to this factor analysis and using regression techniques an analysis is incorporated through structural equations such as Aragon-Correa, Hurtado-Torres, Sharma, and Garcia-Morales (2008), Chen and Chang (2011), Torugsa, O’Donohue, and Hecker (2012) and Vázquez and Sánchez (2013).

To perform this analysis a structural equation modeling (SEM) is used. SEMs are statistical procedures for testing measurement, functional, predictive and causal hypotheses. This multivariate statistical tool is essential to master if one is to understand many bodies of research and to conduct basic or applied research in the behavioral, managerial, health, and social sciences (Bagozzi & Yi, 2011).

The specific literature indicates two stages of the SEM analysis: the assessment of the measurement model (outer model) and the structural model (inner model) (Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins, & Kuppelwieser, 2014; Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012). The measurement model verifies how hypothetical constructs are measured in terms of the observed variables while the structural model examines the relationships between constructs (Chen & Chang, 2011). The structural model is similar to performing a regression analysis but with explanatory power (Vázquez & Sánchez, 2013) studying the direct and indirect effects set of constructs.

The technique chosen within SEM is known as Partial Least Squares (PLS). PLS is an SEM technique based on an iterative approach that maximizes the explained variance of endogenous constructs. This characteristic makes PLS-SEM particularly valuable for exploratory research purposes. Using PLS-SEM in this research is rational for the following reasons. First, PLS-SEM has been broadly used in prior IT research (Chen & Chang, 2011; Pavlou & El Sawy, 2006; Wang et al., 2015a,b). Second, PLS-SEM use is recommended when the theoretical knowledge about a topic is scarce (Hair et al., 2014) as is this case (CSR and technology companies) and also PLS-SEM is more appropriate for causal applications and theory buildings (Henseler et al., 2014; Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012) although it can also be used for confirming all these theories (confirmatory analysis) through the goodness of fit of the global structural model (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015). Third, PLS can estimate models with reflective and formative indicators without problem of identification (Vinzi, Chin, Henseler, & Wang, 2010) because PLS path modeling works with weighted composites rather than factors (Gefen, Rigdon, & Straub, 2011). Fourth, PLS can be estimated models with small samples, in fact, the PLS modeling algorithms tend to get results with high levels of statistical power (Reinartz, Haenlein, & Henseler, 2009), even when the sample size is very modest (Rigdon, 2014). Therefore, we use PLS as statistical tool for management and organizational research as noted by Henseler et al. (2014).

In this study, we used the free software developed by Ringle, Wende and Will in 2005, subject to subscription and authorization of its authors, called SmartPLS. Since SmartPLS is an estimation model and SEM analysis, the estimation process used in two steps evaluating the outer model and the inner model (Hair et al., 2014).

This sequence ensures that we have adequate indicators of constructs before attempting to reach conclusions concerning the relationships included in the inner model (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012).

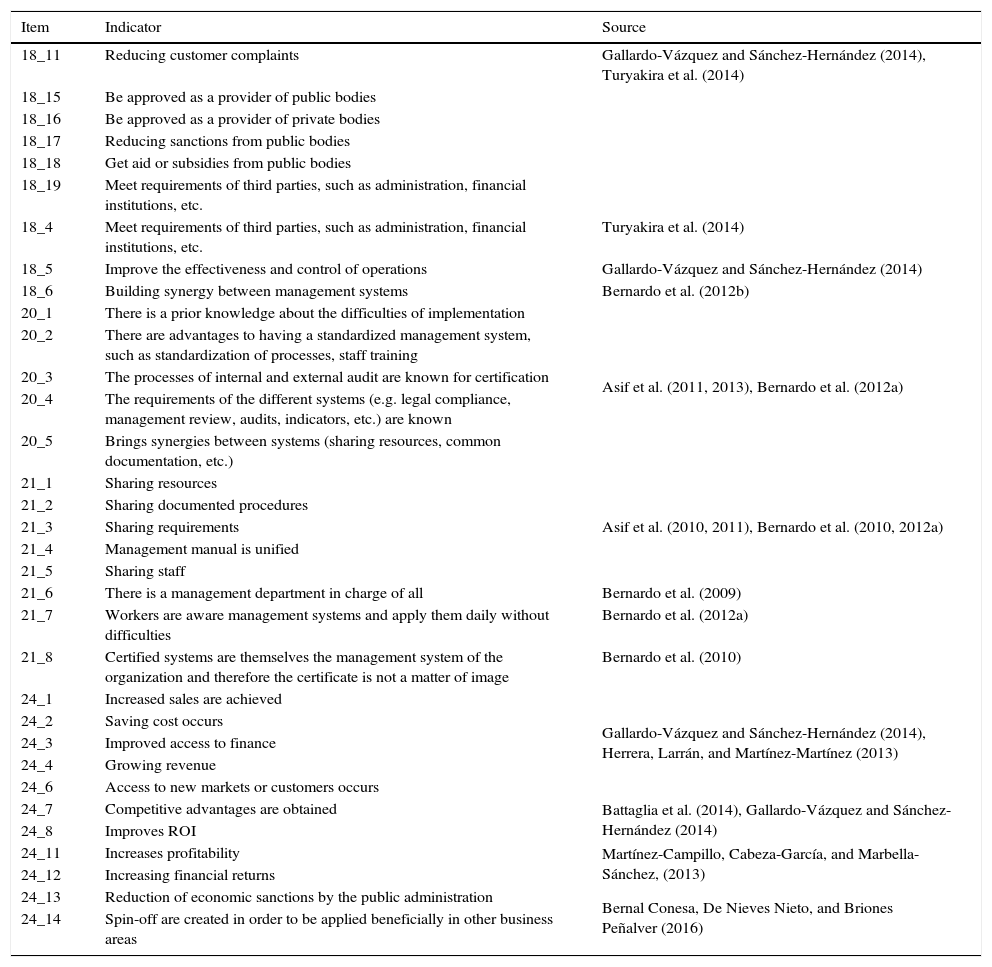

For the measurement of the constructs, different items were defined and collected in a questionnaire (Table 1). These items are based on the literature (e.g. Asif et al., 2011, 2013; Battaglia et al., 2014; Gallardo-Vázquez & Sanchez-Hernandez, 2014; Turyakira et al., 2014). For data collection, a total of 489 invitations were sent by email to access the link to our questionnaire. Finally a total of 98 companies completed the survey, representing a response rate of 20.04%. For surveys using web tools including a link to access the survey, the response rate is around 30% (Arevalo, Aravind, Ayuso, & Roca, 2013) although there are empirical studies with a valid response rate between 10% and 20% (Chow & Chen, 2012; Homburg & Stebel, 2009; Ramos et al., 2014).

Indicators.

| Item | Indicator | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 18_11 | Reducing customer complaints | Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014), Turyakira et al. (2014) |

| 18_15 | Be approved as a provider of public bodies | |

| 18_16 | Be approved as a provider of private bodies | |

| 18_17 | Reducing sanctions from public bodies | |

| 18_18 | Get aid or subsidies from public bodies | |

| 18_19 | Meet requirements of third parties, such as administration, financial institutions, etc. | |

| 18_4 | Meet requirements of third parties, such as administration, financial institutions, etc. | Turyakira et al. (2014) |

| 18_5 | Improve the effectiveness and control of operations | Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014) |

| 18_6 | Building synergy between management systems | Bernardo et al. (2012b) |

| 20_1 | There is a prior knowledge about the difficulties of implementation | Asif et al. (2011, 2013), Bernardo et al. (2012a) |

| 20_2 | There are advantages to having a standardized management system, such as standardization of processes, staff training | |

| 20_3 | The processes of internal and external audit are known for certification | |

| 20_4 | The requirements of the different systems (e.g. legal compliance, management review, audits, indicators, etc.) are known | |

| 20_5 | Brings synergies between systems (sharing resources, common documentation, etc.) | |

| 21_1 | Sharing resources | Asif et al. (2010, 2011), Bernardo et al. (2010, 2012a) |

| 21_2 | Sharing documented procedures | |

| 21_3 | Sharing requirements | |

| 21_4 | Management manual is unified | |

| 21_5 | Sharing staff | |

| 21_6 | There is a management department in charge of all | Bernardo et al. (2009) |

| 21_7 | Workers are aware management systems and apply them daily without difficulties | Bernardo et al. (2012a) |

| 21_8 | Certified systems are themselves the management system of the organization and therefore the certificate is not a matter of image | Bernardo et al. (2010) |

| 24_1 | Increased sales are achieved | Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014), Herrera, Larrán, and Martínez-Martínez (2013) |

| 24_2 | Saving cost occurs | |

| 24_3 | Improved access to finance | |

| 24_4 | Growing revenue | |

| 24_6 | Access to new markets or customers occurs | |

| 24_7 | Competitive advantages are obtained | Battaglia et al. (2014), Gallardo-Vázquez and Sánchez-Hernández (2014) |

| 24_8 | Improves ROI | |

| 24_11 | Increases profitability | Martínez-Campillo, Cabeza-García, and Marbella-Sánchez, (2013) |

| 24_12 | Increasing financial returns | |

| 24_13 | Reduction of economic sanctions by the public administration | Bernal Conesa, De Nieves Nieto, and Briones Peñalver (2016) |

| 24_14 | Spin-off are created in order to be applied beneficially in other business areas |

Hence, the study was conducted in 98 Spanish technology companies located in Science and Technology Parks from February up to December in 2014. From 98 of these questionnaires were valid for this study a total of 50 (response rate of 10.22%), since this is the number of companies that had undertaken (or intended to do so) CSR and had previous management systems.

ResultsOuter modelThe measurement model defines the latent variables that the model will use, and assigns manifest variables to each. The assessment of the measurement model for reflective indicators in PLS is based on individual item reliability, construct reliability, convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Tenenhaus, Vinzi, Chatelin, & Lauro, 2005) and discriminant validity (Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle, & Mena, 2012).

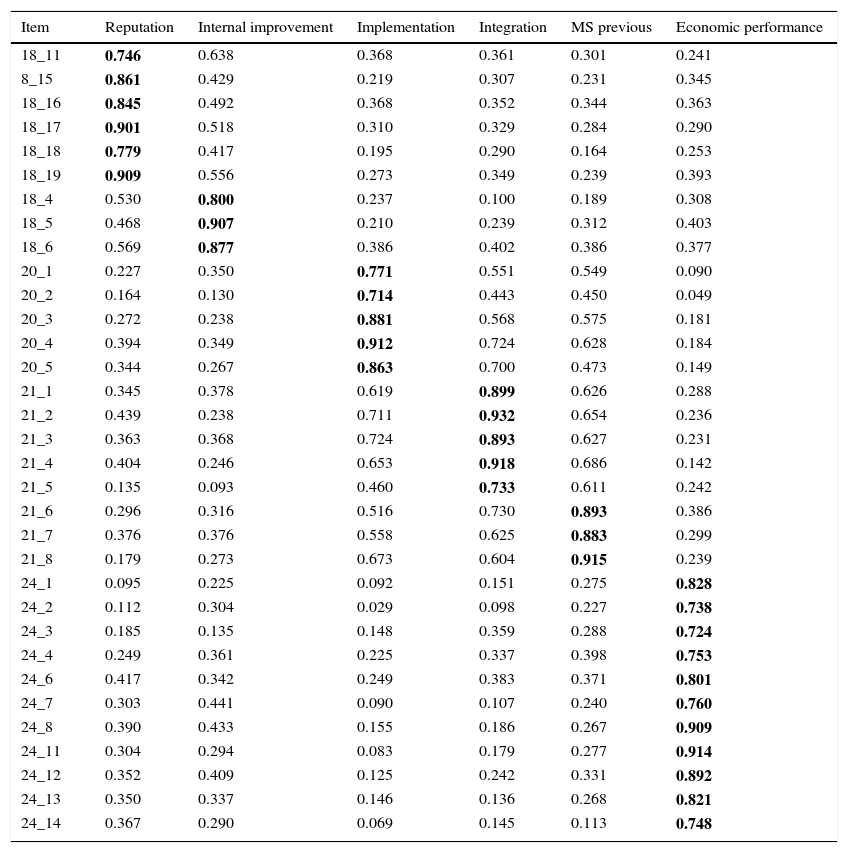

Individual item reliability is assessed by analyzing the standardized loadings (λ), or simple correlations of indicators with their respective latent variable (Hair et al., 2014). Individual item reliability is considered adequate when an item has a λ greater than 0.707 on its respective construct (Carmines & Zeller, 1979). In this study, all reflective indicators have loadings above 0.714 (boldface numbers in Table 2).

Loadings and cross-loadings for the measurement model.

| Item | Reputation | Internal improvement | Implementation | Integration | MS previous | Economic performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18_11 | 0.746 | 0.638 | 0.368 | 0.361 | 0.301 | 0.241 |

| 8_15 | 0.861 | 0.429 | 0.219 | 0.307 | 0.231 | 0.345 |

| 18_16 | 0.845 | 0.492 | 0.368 | 0.352 | 0.344 | 0.363 |

| 18_17 | 0.901 | 0.518 | 0.310 | 0.329 | 0.284 | 0.290 |

| 18_18 | 0.779 | 0.417 | 0.195 | 0.290 | 0.164 | 0.253 |

| 18_19 | 0.909 | 0.556 | 0.273 | 0.349 | 0.239 | 0.393 |

| 18_4 | 0.530 | 0.800 | 0.237 | 0.100 | 0.189 | 0.308 |

| 18_5 | 0.468 | 0.907 | 0.210 | 0.239 | 0.312 | 0.403 |

| 18_6 | 0.569 | 0.877 | 0.386 | 0.402 | 0.386 | 0.377 |

| 20_1 | 0.227 | 0.350 | 0.771 | 0.551 | 0.549 | 0.090 |

| 20_2 | 0.164 | 0.130 | 0.714 | 0.443 | 0.450 | 0.049 |

| 20_3 | 0.272 | 0.238 | 0.881 | 0.568 | 0.575 | 0.181 |

| 20_4 | 0.394 | 0.349 | 0.912 | 0.724 | 0.628 | 0.184 |

| 20_5 | 0.344 | 0.267 | 0.863 | 0.700 | 0.473 | 0.149 |

| 21_1 | 0.345 | 0.378 | 0.619 | 0.899 | 0.626 | 0.288 |

| 21_2 | 0.439 | 0.238 | 0.711 | 0.932 | 0.654 | 0.236 |

| 21_3 | 0.363 | 0.368 | 0.724 | 0.893 | 0.627 | 0.231 |

| 21_4 | 0.404 | 0.246 | 0.653 | 0.918 | 0.686 | 0.142 |

| 21_5 | 0.135 | 0.093 | 0.460 | 0.733 | 0.611 | 0.242 |

| 21_6 | 0.296 | 0.316 | 0.516 | 0.730 | 0.893 | 0.386 |

| 21_7 | 0.376 | 0.376 | 0.558 | 0.625 | 0.883 | 0.299 |

| 21_8 | 0.179 | 0.273 | 0.673 | 0.604 | 0.915 | 0.239 |

| 24_1 | 0.095 | 0.225 | 0.092 | 0.151 | 0.275 | 0.828 |

| 24_2 | 0.112 | 0.304 | 0.029 | 0.098 | 0.227 | 0.738 |

| 24_3 | 0.185 | 0.135 | 0.148 | 0.359 | 0.288 | 0.724 |

| 24_4 | 0.249 | 0.361 | 0.225 | 0.337 | 0.398 | 0.753 |

| 24_6 | 0.417 | 0.342 | 0.249 | 0.383 | 0.371 | 0.801 |

| 24_7 | 0.303 | 0.441 | 0.090 | 0.107 | 0.240 | 0.760 |

| 24_8 | 0.390 | 0.433 | 0.155 | 0.186 | 0.267 | 0.909 |

| 24_11 | 0.304 | 0.294 | 0.083 | 0.179 | 0.277 | 0.914 |

| 24_12 | 0.352 | 0.409 | 0.125 | 0.242 | 0.331 | 0.892 |

| 24_13 | 0.350 | 0.337 | 0.146 | 0.136 | 0.268 | 0.821 |

| 24_14 | 0.367 | 0.290 | 0.069 | 0.145 | 0.113 | 0.748 |

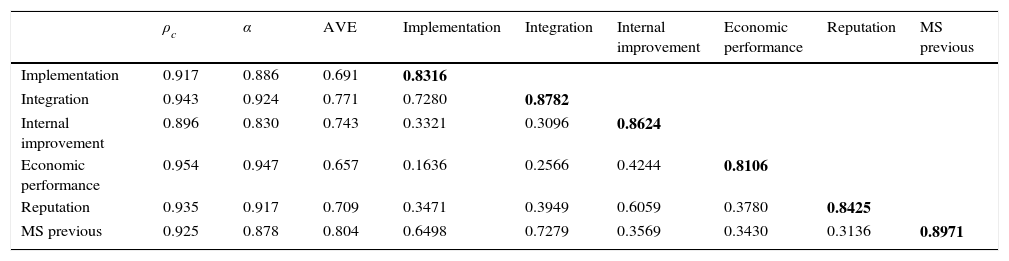

The reliability of a construct, also known as internal consistency, allows to assess what extended indicators (observable variables) are measuring the constructs (latent variables). Construct reliability is usually assessed using composite reliability (ρc) (Hair et al., 2014) and Cronbach's alpha (Castro & Roldán, 2013). Following the guidelines proposed by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), for both sets of values, one can be taken 0.7 as a benchmark for a modest reliability applicable in the early stages of research. Particularly, in our research, all constructs present values above 0.7 (Table 3), thus confirming their internal consistency.

Composite reliability (ρc), convergent and discriminant validity coefficients.

| ρc | α | AVE | Implementation | Integration | Internal improvement | Economic performance | Reputation | MS previous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation | 0.917 | 0.886 | 0.691 | 0.8316 | |||||

| Integration | 0.943 | 0.924 | 0.771 | 0.7280 | 0.8782 | ||||

| Internal improvement | 0.896 | 0.830 | 0.743 | 0.3321 | 0.3096 | 0.8624 | |||

| Economic performance | 0.954 | 0.947 | 0.657 | 0.1636 | 0.2566 | 0.4244 | 0.8106 | ||

| Reputation | 0.935 | 0.917 | 0.709 | 0.3471 | 0.3949 | 0.6059 | 0.3780 | 0.8425 | |

| MS previous | 0.925 | 0.878 | 0.804 | 0.6498 | 0.7279 | 0.3569 | 0.3430 | 0.3136 | 0.8971 |

Note. Diagonal elements (bold) are the square root of the variance shared between the constructs and their measures (average variance extracted). Off-diagonal elements are the correlations among constructs. For discriminant validity, diagonal elements should be larger than off-diagonal elements.

Convergent validity is an assessment whether various items designed to measure a construct actually do it. To assess convergent validity, we examine the average variance extracted (AVE). This parameter expresses the amount of variance that a construct obtains from its indicators as against the amount due to measurement error. AVE values should be higher than 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), which means that 50 per cent -or more- of variance of indicators should be accounted for the construct (Hair et al., 2014).

Discriminant validity indicates the extent to which a given construct differs from other constructs. There are two approaches to assess discriminant validity (Gefen & Straub, 2005). On one hand, Fornell and Larcker (1981) suggest the use of the average variance shared between a construct and its measures (AVE). This measure should be higher than the shared variance between the construct and other constructs in the model. To put this idea into operation, the AVE square root of each construct should be greater than its correlations with any other construct in the assessment. This condition is satisfied by all constructs in relation to their other variables (Table 3).

On the other hand, the second approach suggests that each item should load more highly on its assigned construct than others (Henseler, Ringle, & Sinkovics, 2009; Lee, Petter, Fayard, & Robinson, 2011). In addition, each construct should load higher with its assigned indicators than other items (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012). This cross-loading analysis may be performed calculating the correlations between the construct scores and the standardized data of the indicators (Gefen et al., 2011). As can be observed in Table 2 that condition was satisfied.

Inner modelOnce the reliability and validity of the outer models is established, several steps need to be taken to evaluate the hypothesized relationships within the inner model (Hair et al., 2014). The inner model is basically assessed according to the meaningfulness and significance of the relationships hypothesized between the constructs.

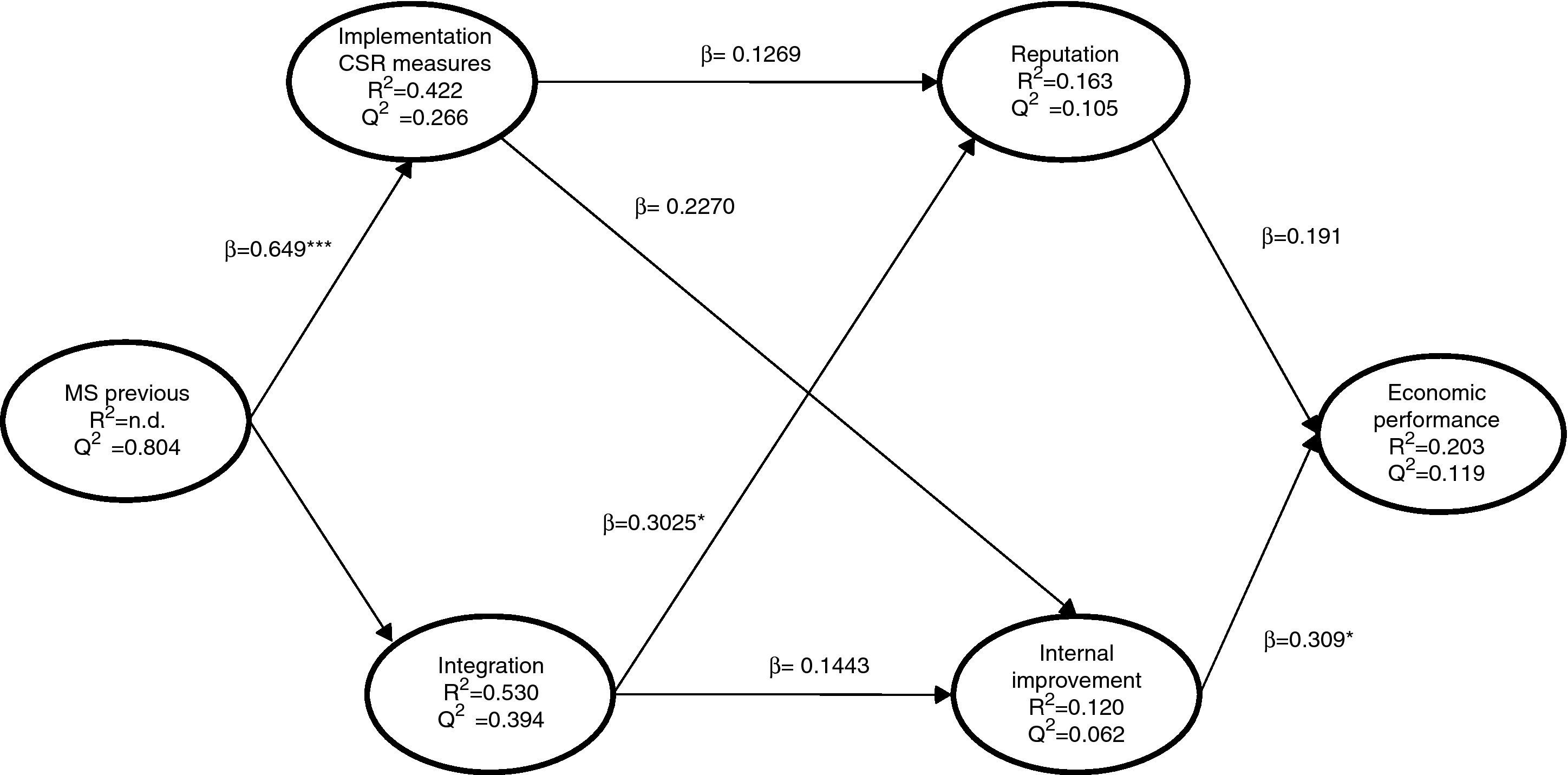

The assessment of the model's quality is based on its ability to predict endogenous constructs. The following criteria facilitate this assessment (Hair et al., 2014): path coefficients (β) and their significance levels (t-student), coefficient of determination (R2) and cross-validated redundancy (Q2).

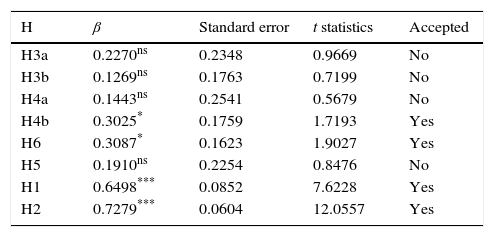

First, we tested the significance of all the paths from the structural model. Standardized path coefficients allow to analyze the degree of accomplishment the hypotheses. In this regard, Chin (1998) proposed that the analysis should provide standardized path coefficients exceeding values greater than 0.2 and ideally 0.3 whether β<0.2 there is no causality and the hypothesis is rejected (Chin, 1998). Consistent with Hair, Ringle, and Sarstedt (2011) and Henseler et al. (2009), bootstrapping (5000 resamples) was used to generate standard errors and t-statistics. This enabled us to assess the statistical significance of the path coefficients (Castro & Roldán, 2013). At the same time, the bootstrapping confidence interval of standardized regression coefficients was given and accepted (or not) the hypothesis. Table 4 shows the β standardized regression coefficients named “path coefficients” in SEM jargon.

Hypothesis testing.

| H | β | Standard error | t statistics | Accepted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H3a | 0.2270ns | 0.2348 | 0.9669 | No |

| H3b | 0.1269ns | 0.1763 | 0.7199 | No |

| H4a | 0.1443ns | 0.2541 | 0.5679 | No |

| H4b | 0.3025* | 0.1759 | 1.7193 | Yes |

| H6 | 0.3087* | 0.1623 | 1.9027 | Yes |

| H5 | 0.1910ns | 0.2254 | 0.8476 | No |

| H1 | 0.6498*** | 0.0852 | 7.6228 | Yes |

| H2 | 0.7279*** | 0.0604 | 12.0557 | Yes |

Note: t(0.05, 4999)=1.645158499, t(0.01, 4999)=2.327094067, t(0.001, 4999)=3.091863446.

Second, the goodness of a model is determined by the strength of each structural path (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014). This was analyzed by using the R2 value (explained variance) for dependent latent variables. Hence, for each path between constructs, the desirable values should be at least equal to or higher than 0.1 (Falk & Miller, 1992).

The R2 is a measure of the model's predictive accuracy (Hair et al., 2014) and therefore R2 values measure the construct variance explained by the model (Serrano-Cinca, Fuertes-Callén, & Gutiérrez-Nieto, 2007) with 0.75, 0.50, 0.25, respectively, describing substantial, moderate, or weak levels of predictive accuracy (Hair et al., 2011). As it can be seen in Fig. 2, all R2 values remain between 0.1 and 0.75, so it has a predictive capability in varying degrees.

Finally, Stone-Giesser's test or Cross-validated redundancy index (Q2) is used to assess the predictive relevance of endogenous constructs with a reflective measurement model (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012; Wang et al., 2015a,b). Therefore, it means for assessing the inner model's predictive relevance (Hair et al., 2014). This test is an indicator of how well observed values are reproduced by the model and its estimates parameter. The cross-validated redundancy index (Q2) is used for endogenous reflective constructs (Castro & Roldán, 2013). A Q2 greater than 0 implies that the model has predictive relevance, whereas a Q2 less than 0 suggests that is lacking in the model (Castro & Roldán, 2013; Hair et al., 2014). According to this, it can be said that there is significance in the prediction of the constructs because a positive Q2 value is obtained (Fig. 3).

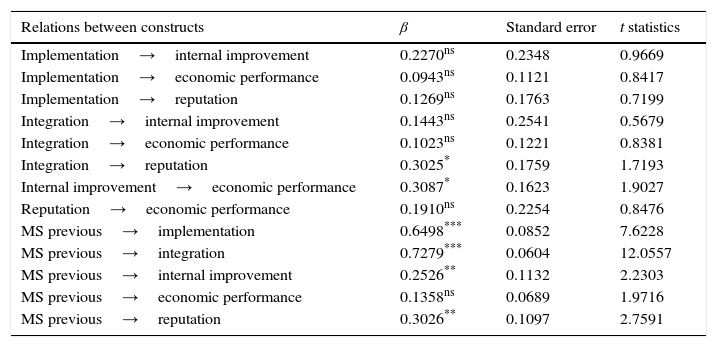

Vázquez and Sánchez (2013) claim that full effects (direct and indirect) have to be considered. Theses effects are reflected in Table 5.

Full effects (direct and indirect).

| Relations between constructs | β | Standard error | t statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation→internal improvement | 0.2270ns | 0.2348 | 0.9669 |

| Implementation→economic performance | 0.0943ns | 0.1121 | 0.8417 |

| Implementation→reputation | 0.1269ns | 0.1763 | 0.7199 |

| Integration→internal improvement | 0.1443ns | 0.2541 | 0.5679 |

| Integration→economic performance | 0.1023ns | 0.1221 | 0.8381 |

| Integration→reputation | 0.3025* | 0.1759 | 1.7193 |

| Internal improvement→economic performance | 0.3087* | 0.1623 | 1.9027 |

| Reputation→economic performance | 0.1910ns | 0.2254 | 0.8476 |

| MS previous→implementation | 0.6498*** | 0.0852 | 7.6228 |

| MS previous→integration | 0.7279*** | 0.0604 | 12.0557 |

| MS previous→internal improvement | 0.2526** | 0.1132 | 2.2303 |

| MS previous→economic performance | 0.1358ns | 0.0689 | 1.9716 |

| MS previous→reputation | 0.3026** | 0.1097 | 2.7591 |

Note: t(0.05, 4999)=1.645158499, t(0.01, 4999)=2.327094067, t(0.001, 4999)=3.091863446.

These results confirmed four of the relations established in the research model. It can be see a clear influence on the standardized management systems prior to the implementation of CSR measures and their integration into the companies to improve their reputation. At the same time, we can see that some indirect effects on internal improvement and reputation by previous management systems occur (see Table 5) in line with other studies (Battaglia et al., 2014). However, we must reject the hypothesis H3, H6, and H7 because β value does not allow supporting such causality. It also has to be rejected H5 because is not getting an adequate significant level.

Conclusions and discussionThrough the study, it is intended to fill the gap identified in the literature on technology companies to implement CSR measures. Although there are preliminary studies for CSR, integration and results in Spanish companies, these are done from a regional perspective (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sanchez-Hernandez, 2014; Vintró, Fortuny, Sanmiquel, Freijo, & Edo, 2012) or analyzing a unique aspect of this relationship (Prado-Lorenzo, Gallego-Álvarez, García-Sánchez, & Rodríguez-Domínguez, 2008). Thus, the absence of previous empirical studies analyzing the relations of CSR in the Spanish Technology Sector and their integration into the company justified its implementation, and considers that adding a supplement research studies linking CSR and integration. Because this relationship is not only studied with a direct effect but also incorporates an indirect relationship through previous systems management on internal improvement and reputation.

The integration of socially responsible measures not only results in an ethical or moral positioning of the organizations, but also in generating high strategic intangibles value, such as the external reputation of the company.

The main contribution of this paper has been to demonstrate the link between CSR and its integration in technology companies empirically and reliably. From a practical standpoint companies can use the results of this study as a foothold to enhance the integration of CSR based on previous systems and exploit the synergies between them, since the integration of CSR has a direct relationship with the reputation of the company.

Nevertheless, the failure to find a significant relationship between the integration of CSR and economic performance is in line with other studies (Pamiés & Jiménez, 2011). This could be explained by the possibility that the case of an indirect or moderate relationship by other variables in what has been called the triple bottom line (TBL) (Miras Rodriguez, del, Carrasco Gallego, & Escobar Perez, 2014). TBL simultaneously considers the economic performance, social and environmental issues (Gimenez, Sierra, & Rodon, 2012; Miralles Marcelo, Miralles Quirós, del, & Miralles Quirós, 2012). In fact, some authors consider that organizations with CSR try to balance the TBL (Lo, 2010).

Ultimately, the proactive management of stakeholders can lead to a reduction of short-term profit, but long-term impact of these actions can be positive in terms of financial (Garcia-Castro et al., 2009) and environmental performance since awareness and dissemination of CSR activities by businesses can have a positive effect toward environmental protection (Gallardo-Vázquez & Sánchez-Hernández, 2014). Hence, it arise a future line of research which could propose a model of integration in technology companies where the environmental and social-performance and its impact on economic performance could be studied. Moreover, the application of environmental controls, although they may be a short-term cost, long-term can report environmental benefits if variable is positively perceived by customers.

In empirical studies, it is important to identify and consider limitations when achieve interpretations and conclusions.

First of all, an initial limitation is related to the notion of causality. Although the evidence is provided by causality model, this has not really been tested. This study has an associative modeling approach, since it is directed toward the prediction of causality. While causality guarantees the ability to handle events, the association (prediction) only allows a limited degree of control (Falk & Miller, 1992).

Second, another limitation is determined by the technique used for the proposed model: structural equation, which assumes linearity of the relationship between the latent variables (Castro & Roldán, 2013).

Third, technology companies are dynamic organizations that change over time. Consequently, future research should measure the same constructs analyzed over several time periods, taking into account the dynamics to configure the different dimensions of CSR.

However, given the above limitations, the work could be seen as pioneer since it represents a starting point the aspects of CSR in any technology company and covers the gap identified in the literature.