Simulation-based learning has proven to be an effective tool for recreating real-life scenarios. Simulation provides a controlled environment where students can practice skills in a realistic case setting. However, there is a lack of research on the opinions and experiences of physiotherapy students undergoing simulation-based training. This study aimed to assess the effectiveness and student satisfaction after a simulation focused on chronic pain.

MethodsA mixed-methods approach was employed to investigate the effectiveness of simulation-based learning with a biopsychosocial approach in the context of chronic pain patients in physiotherapy.

ParticipantsThe study included 66 students who participated in two simulation experiences. The students completed a questionnaire consisting of open-ended questions and Likert-scale responses. The open-ended responses were analyzed using Giorgi's method.

El aprendizaje basado en simulación ha demostrado ser una herramienta efectiva para recrear escenarios de la vida real. La simulación proporciona un entorno controlado para que los estudiantes practiquen habilidades en un escenario de caso realista. Sin embargo, existe una falta de investigación sobre las opiniones y experiencias de los estudiantes de fisioterapia que se someten a entrenamiento mediante simulación. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo evaluar la efectividad y satisfacción de los estudiantes de fisioterapia después de una simulación centrada en el dolor crónico.

MétodosSe empleó un enfoque de métodos mixtos para investigar la efectividad del aprendizaje basado en simulación con un enfoque biopsicosocial en el contexto de pacientes con dolor crónico en fisioterapia.

ParticipantesEn el estudio participaron 66 estudiantes en dos experiencias de simulación. Los estudiantes completaron un cuestionario que comprendía preguntas abiertas con respuestas en escala Likert. Las respuestas abiertas fueron analizadas utilizando el método de Giorgi.

ResultadosLas experiencias de los estudiantes se categorizaron en cuatro temas: percepciones personales, habilidades adquiridas, transferencia del rol profesional y satisfacción. Se reportaron calificaciones de satisfacción positivas en todos los ámbitos. La adquisición de habilidades y habilidades de pensamiento crítico se demostraron consistentemente en todas las áreas.

ConclusionesLa simulación demuestra ser una herramienta valiosa para capacitar a los estudiantes de fisioterapia en la interacción y tratamiento eficaz de pacientes con dolor crónico. El aprendizaje basado en simulación ha demostrado mejorar la adquisición de habilidades y competencias, mientras satisface las experiencias de aprendizaje de los estudiantes.

Simulation-based learning (SBL) is increasingly recognized as a crucial tool for skill and knowledge acquisition in undergraduate healthcare education, particularly in physiotherapy. It immerses students in realistic scenarios, enhancing their learning experience with immediate feedback from clinical educators.1 Studies indicate that SBL boosts confidence in acute care clinical practice within physiotherapy programs2,3 and is as effective as other educational strategies, especially in the early stages of these programs.4,5 However, its application in teaching the psychosocial factors of chronic pain is less explored.

The physiotherapy curriculum typically encompasses 240 ECTS credits, including internships where students face real-life clinical challenges. This phase is crucial, as underprepared students might struggle, affecting both patient care and the health center's reputation. SBL, more a technique than technology, replicates real-world scenarios in a controlled setting, reducing patient risk and enhancing theoretical knowledge application.4,6

Chronic pain, affecting a significant portion of the global population, poses a substantial socioeconomic burden.7,8 Physiotherapy's shift to a biopsychosocial model from a pathoanatomical one marks a crucial development in pain management.9,10 This model considers pain as a complex response involving the brain's evaluation of harmful signals, and the flag system assists in identifying chronic pain predictors.11

Teaching this model equips students with a holistic understanding of pain, aiding in the development of effective treatment plans and improving patient communication. This approach is beneficial not just for managing pain but also for overall patient well-being.12,13 Additionally, physiotherapy and nursing students’ experience levels positively influence their skills and confidence,4 with improvements seen in critical thinking and clinical skills following SBL in acute illness management.14

Emerging research supports integrating SBL into physiotherapy programs, as it provides practical scenarios for developing critical thinking, communication, and psychosocial clinical interpretation skills.14,15 Our research suggests that SBL in chronic pain and psychosocial contexts is particularly effective, enhancing satisfaction, self-perceived skills, and confidence more than other teaching methods.16,17

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the learning effectiveness and satisfaction of physiotherapy students following a simulation involving chronic pain patients. The simulation required students to apply their understanding of pain neuroscience education and identify psychosocial factors in the patients.

The specific objectives of the study were as follows: (1) Assess the students’ ability to identify biopsychosocial factors associated with chronic pain; (2) Analyze the effectiveness of the students’ explanations to the patients; (3) Evaluate the students’ critical thinking skills when discussing treatment strategies for chronic pain.

MethodsDesignA mixed-method study was employed to explore and evaluate the effectiveness of simulation-based learning (SBL) a within the biopsychosocial approach for chronic pain patients in the field of physiotherapy. Mixed methods research is a research approach in which researchers combine qualitative and quantitative elements to achieve a comprehensive understanding and validation of findings.18,19 In our study, the qualitative data was used to support and corroborate the results obtained from the assessment of competencies observed by the professors.

Given the nature of our objectives and the complex nature of the educational process, both qualitative and quantitative approaches were deemed necessary. Understanding the experiences and beliefs of physiotherapy students requires a qualitative research design.20 We opted for an observational case study research design to meet our objectives.21 The emphasis in data collection was on interviews, archival records, and observations to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms and reasons behind observed phenomena, thereby leading to theoretical conclusions.21

Context and participantsThis research was conducted as part of the curriculum in “Assessment 1”, “Physiotherapy Methods 2”, and “Psychology” courses, specifically in the first, third, and fourth years of the degree program respectively. Simulation was employed as a training strategy within these courses. The reporting of qualitative research followed the guidelines outlined by O’Brien et al.22

The inclusion criteria for participants in this study were enrollment in the dual degree program in Physiotherapy, successful completion of prerequisite courses, and signing a consent form for data usage. A total of 67 students participated in two simulation sessions conducted by experienced professors from the dual degree program. The simulation activities were voluntary and did not contribute to participants’ final grades in the courses. All participants completed the simulation, consisting of three phases (pre-briefing, scenario, and debriefing), and filled out a questionnaire at the conclusion of the session. There was no participant attrition rate.

After completing the classroom-based curriculum on psychosocial factors and pain pedagogy, students were given the opportunity to reinforce, consolidate, and self-assess the knowledge they had acquired through the simulation experience. The simulation encompassed five clinical cases of chronic pain from various disciplines, including chronic pelvic pain, cervical whiplash, chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia syndrome, and chronic low back pain. A high-fidelity simulation was conducted with professional actors trained in different chronic pain scenarios.

The clinical simulation process followed the standard structure of pre-briefing, scenario execution, and debriefing. Pre-briefing sessions were conducted in two separate groups, each lasting approximately 20minutes, to provide information and address any queries regarding objectives, context, and available human and material resources. The simulation scenario involved pairs of students interacting for a duration of 10minutes, while other students observed the simulation on a screen through hidden cameras installed in the simulation room. Following the simulation experience, a debriefing session was facilitated by a simulation expert and three professors who specialized in chronic pain. This 10-minute debriefing involved discussing the different outcomes of the experience, the students’ critical thinking processes, and their personal perceptions when confronted with a real case.

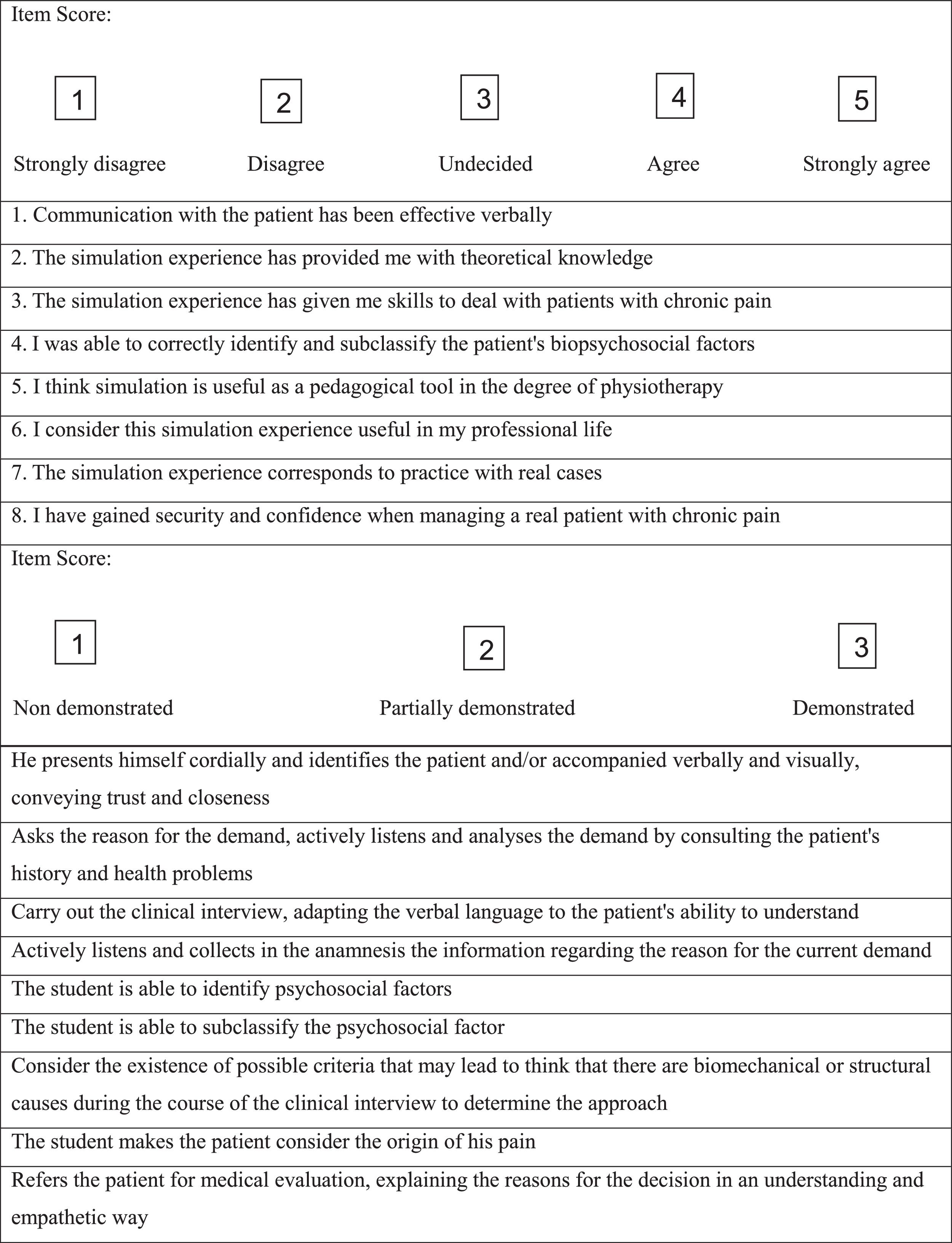

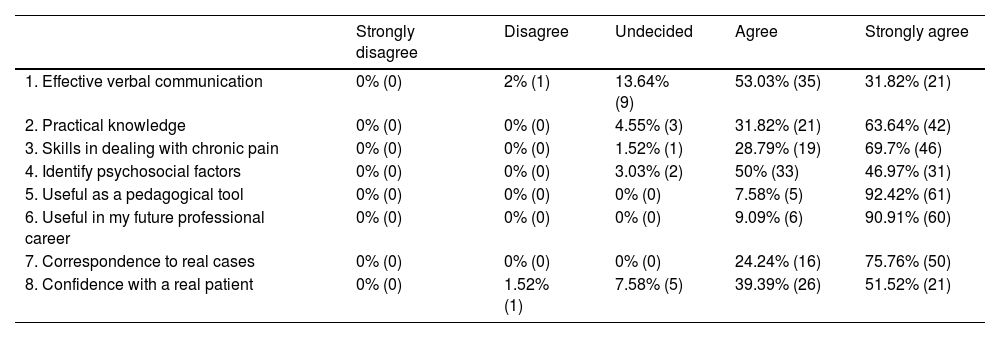

Data collectionThe team of expert professors in chronic pain developed various tools to gather data on the simulation experience. These tools were employed to capture students’ experiences, evaluate their satisfaction levels, and assess the skills demonstrated during the simulation using a rubric. Student's satisfaction was measured through an eight-question satisfaction questionnaire, utilizing a Likert scale response format (refer to Table 1). The questionnaire was specifically designed to evaluate satisfaction with simulation-based learning (SBL) in comparison to the training evaluation model, aiming to gauge students’ engagement levels.23 Additionally, an open-ended question, “What have you experienced in the simulation?”, was included at the end of the questionnaire to encourage students to freely express their thoughts and feelings. The simulation sessions took place aligning with the schedule of the university curriculum.

A skills rubric was also developed to assess students’ communication skills and critical thinking processes. The rubric is shown in Table 1.

Data analysisThe quantitative data were analyzed descriptively using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (SPSS Armonk NY, IBM Corp.) statistical software package. As for the qualitative data obtained from the questionnaire, the Giorgi qualitative analysis method20,24 was employed. This method was chosen to systematically generate a theoretical understanding of the emerging concepts from the data and explore participants’ experiences with the simulation. Giorgi's method falls within the realm of phenomenological research, which focuses on studying individuals’ subjective experiences and the meanings they ascribe to those experiences. The analysis procedure involves four steps: (1) reading for general information on the theme, (2) identification of units of meaning, (3) grouping and comparing similar units of meaning, and (4) synthesizing categories to form the main concepts.25 In our study, four independent researchers conducted the analysis, subsequently reaching an agreement that demonstrated a high degree of consensus. Whenever there was a lack of consensus in the coding of specific units of analysis, differing arguments were presented and discussed until agreement was achieved in nearly all cases. However, in instances where consensus could not be reached among the researchers, an external expert was involved in the analysis process to provide additional insight.

ResultsA total of 66 physiotherapy students (29 females and 37 males) were evaluated, representing 29.4% and 70.5% of the sample, respectively. The students’ ages ranged from 18 to 42 years, with an average age of 20.37 years (±3.10 years). Only one student declined to sign the informed consent, resulting in a negligible loss of data. The results were derived from the analysis of 66 questionnaires and skills rubrics collected from participants enrolled in the first, third, and fourth courses. The majority of students had completed their secondary education, and none of them had prior experience with simulation.

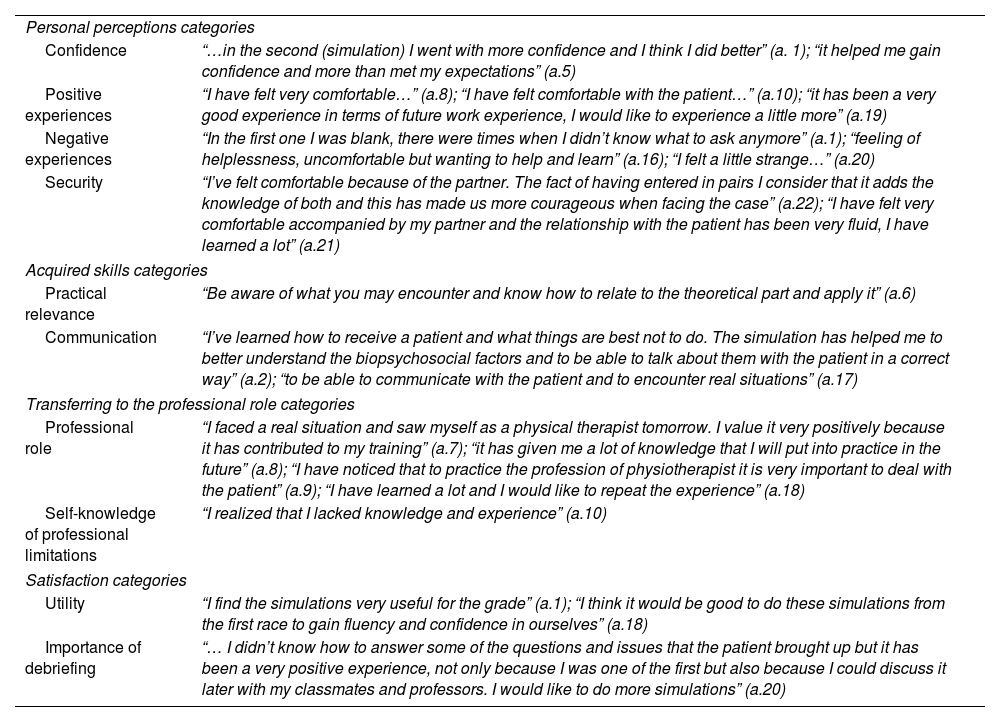

Qualitative data: experiencesThe participants were encouraged to provide their unrestricted thoughts and feelings regarding the simulation experience by responding to the open-ended question, “What experiences have you had in the simulation?” The responses to this question were subjected to qualitative data analysis using the Giorgi method. The analysis yielded four main categories of findings: (1) personal perceptions, (2) acquired skills, (3) transfer of the professional role, and (4) satisfaction. Each category encompasses various sub-themes, capturing the diverse aspects of the participants’ experiences during the simulation.

In the forthcoming sections, the tables encapsulating the categorized themes derived from the qualitative analysis will be presented for review. The qualitative results are shown in Table 2.

Qualitative results.

| Personal perceptions categories | |

| Confidence | “…in the second (simulation) I went with more confidence and I think I did better” (a. 1); “it helped me gain confidence and more than met my expectations” (a.5) |

| Positive experiences | “I have felt very comfortable…” (a.8); “I have felt comfortable with the patient…” (a.10); “it has been a very good experience in terms of future work experience, I would like to experience a little more” (a.19) |

| Negative experiences | “In the first one I was blank, there were times when I didn’t know what to ask anymore” (a.1); “feeling of helplessness, uncomfortable but wanting to help and learn” (a.16); “I felt a little strange…” (a.20) |

| Security | “I’ve felt comfortable because of the partner. The fact of having entered in pairs I consider that it adds the knowledge of both and this has made us more courageous when facing the case” (a.22); “I have felt very comfortable accompanied by my partner and the relationship with the patient has been very fluid, I have learned a lot” (a.21) |

| Acquired skills categories | |

| Practical relevance | “Be aware of what you may encounter and know how to relate to the theoretical part and apply it” (a.6) |

| Communication | “I’ve learned how to receive a patient and what things are best not to do. The simulation has helped me to better understand the biopsychosocial factors and to be able to talk about them with the patient in a correct way” (a.2); “to be able to communicate with the patient and to encounter real situations” (a.17) |

| Transferring to the professional role categories | |

| Professional role | “I faced a real situation and saw myself as a physical therapist tomorrow. I value it very positively because it has contributed to my training” (a.7); “it has given me a lot of knowledge that I will put into practice in the future” (a.8); “I have noticed that to practice the profession of physiotherapist it is very important to deal with the patient” (a.9); “I have learned a lot and I would like to repeat the experience” (a.18) |

| Self-knowledge of professional limitations | “I realized that I lacked knowledge and experience” (a.10) |

| Satisfaction categories | |

| Utility | “I find the simulations very useful for the grade” (a.1); “I think it would be good to do these simulations from the first race to gain fluency and confidence in ourselves” (a.18) |

| Importance of debriefing | “… I didn’t know how to answer some of the questions and issues that the patient brought up but it has been a very positive experience, not only because I was one of the first but also because I could discuss it later with my classmates and professors. I would like to do more simulations” (a.20) |

In terms of personal perceptions, the students shared their reflections on themes such as confidence, security, and both positive and negative experiences. They expressed that they observed improvements compared to their initial experience. However, contrasting feelings emerged from the overall simulation experience. While some students felt uncomfortable, others expressed a desire to push their limits further.

Acquired skills categoriesThe students also reflected on the skills they believed they possessed. They emphasized the significance of simulation in applying the communication skills they had acquired in the classroom.

Transferring to the professional role categoriesStudents expressed their views on the applicability of simulation in their future professional roles, acknowledging its potential benefits. They recognized the value of simulation in preparing them for real clinical practice. However, they also became aware of its limitations and identified areas where simulation may not fully replicate the complexity of actual patient encounters.

Satisfaction categoriesIn the satisfaction category, students provided feedback on the usefulness of the simulation in the field of physiotherapy and emphasized the significance of the debriefing process for integrating their learning. They expressed satisfaction with the overall simulation experience and highlighted its positive impact on their professional development. The debriefing sessions were particularly valued as they allowed students to reflect on their performance, receive constructive feedback, and further enhance their understanding of the biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain management.

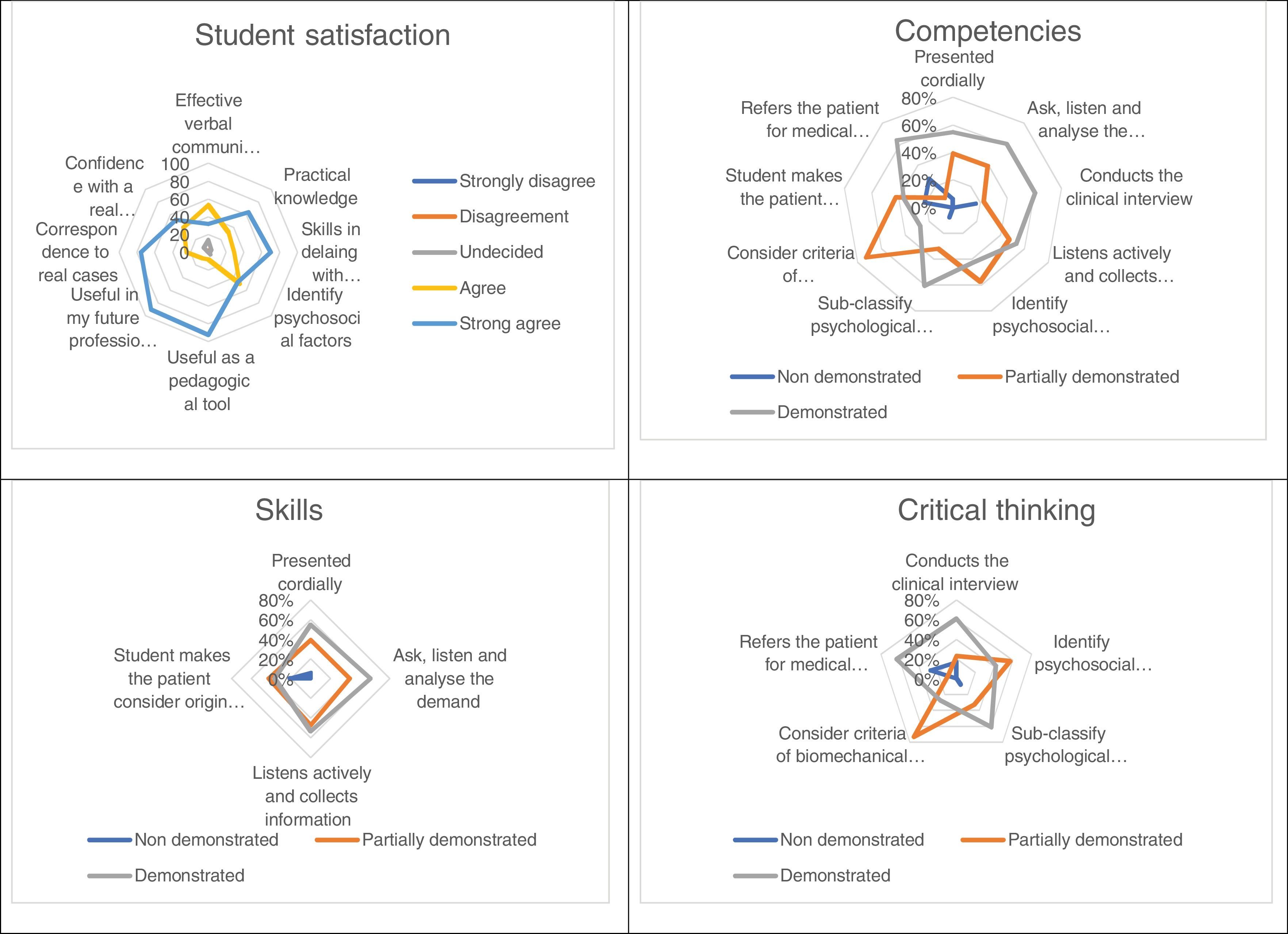

Quantitative: student satisfactionThe questionnaires were completed by all of the students, resulting in a 100% response rate. The statistical analysis revealed the levels of satisfaction expressed by the students for each question.

The data in Table 3 show a student satisfaction survey with a clear lean towards positive responses. For all the evaluated aspects, such as effective verbal communication, practical knowledge, and skills in dealing with chronic pain, the majority of students have given high satisfaction ratings, with ‘Agree’ and ‘Strongly agree’ percentages combined to form the bulk of the responses. The highest levels of strong agreement are seen in the appraisal of the course's practical knowledge and its utility in future professional careers, indicating that students find the content both relevant and applicable.

Student satisfaction results.

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Undecided | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Effective verbal communication | 0% (0) | 2% (1) | 13.64% (9) | 53.03% (35) | 31.82% (21) |

| 2. Practical knowledge | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 4.55% (3) | 31.82% (21) | 63.64% (42) |

| 3. Skills in dealing with chronic pain | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 1.52% (1) | 28.79% (19) | 69.7% (46) |

| 4. Identify psychosocial factors | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 3.03% (2) | 50% (33) | 46.97% (31) |

| 5. Useful as a pedagogical tool | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 7.58% (5) | 92.42% (61) |

| 6. Useful in my future professional career | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 9.09% (6) | 90.91% (60) |

| 7. Correspondence to real cases | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 24.24% (16) | 75.76% (50) |

| 8. Confidence with a real patient | 0% (0) | 1.52% (1) | 7.58% (5) | 39.39% (26) | 51.52% (21) |

The aspect of dealing with chronic pain also sees a particularly high level of strong agreement, suggesting that the course effectively prepares students for this challenging area. The use of pedagogical tools and the correspondence of course content to real cases is also highlighted as particularly positive, with the vast majority of students expressing strong agreement in these areas.

Notably, disagreement is very minimal across the board, and very few students are undecided, which underscores a confident endorsement of the course's effectiveness. The combination of agreement and strong agreement for confidence with a real patient indicates that students feel well-prepared for practical application of their skills.

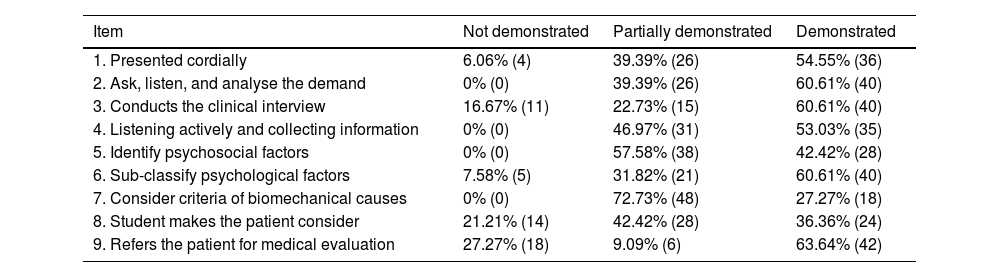

Quantitative: acquired skillsThe data analysis reveals positive outcomes regarding the acquisition of competencies. These findings are based on the assessments conducted by the professors during the simulation experience. A total of nine items were evaluated, representing various observed competencies. Notably, considering that a portion of the students had just completed their first course in physiotherapy, the satisfactory results across most of the assessed items are remarkable. This indicates that the simulation experience effectively contributes to the development of essential skills and knowledge in the early stages of the students’ physiotherapy education. The results are shown in Table 4.

Acquired skills results.

| Item | Not demonstrated | Partially demonstrated | Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Presented cordially | 6.06% (4) | 39.39% (26) | 54.55% (36) |

| 2. Ask, listen, and analyse the demand | 0% (0) | 39.39% (26) | 60.61% (40) |

| 3. Conducts the clinical interview | 16.67% (11) | 22.73% (15) | 60.61% (40) |

| 4. Listening actively and collecting information | 0% (0) | 46.97% (31) | 53.03% (35) |

| 5. Identify psychosocial factors | 0% (0) | 57.58% (38) | 42.42% (28) |

| 6. Sub-classify psychological factors | 7.58% (5) | 31.82% (21) | 60.61% (40) |

| 7. Consider criteria of biomechanical causes | 0% (0) | 72.73% (48) | 27.27% (18) |

| 8. Student makes the patient consider | 21.21% (14) | 42.42% (28) | 36.36% (24) |

| 9. Refers the patient for medical evaluation | 27.27% (18) | 9.09% (6) | 63.64% (42) |

The data from Table 4 indicate an assessment of specific acquired skills, with the focus on the frequency of demonstration among participants. For each skill, there's a clear majority that either partially demonstrated or fully demonstrated the skills, as very few skills were not demonstrated at all. For instance, in the skill to “Ask, listen, and analyze the demand,” no one failed to demonstrate the skill, and over 60% fully demonstrated it.

The skills “Listening actively and collecting information” and “Sub-classify psychological factors” also show strong full demonstration, indicating these areas are well covered by the participants’ education or training.

In Fig. 1, competencies were categorized into two main areas: skills and critical thinking. Skills were evaluated based on competencies such as presenting cordially, asking appropriate questions, actively listening and gathering information, and encouraging patient engagement. On the other hand, critical thinking was assessed through competencies related to conducting a comprehensive clinical interview, identifying and categorizing psychosocial factors, considering biomechanical causes as criteria, and making appropriate referrals for medical evaluation. These competencies are crucial in facilitating effective clinical decision-making and ensuring the delivery of quality care to patients. The results of satisfaction and competencies are shown in Fig, 1.

DiscussionThis study provides significant insights into simulation-based learning (SBL) in physiotherapy education, particularly focusing on chronic pain management. SBL effectively connects theoretical knowledge with practical skills crucial for patient care in chronic pain. However, there is limited literature on using simulations for the biopsychosocial aspects of chronic pain, an area requiring proficient communication skills and understanding of patients’ emotional and psychological states.26

A triangulation approach in data analysis reveals the relationship between skill acquisition and student satisfaction. There is a positive correlation between students’ confidence in their skills and their satisfaction with the educational program, suggesting effective curriculum design. However, this study identifies a gap in acquiring psychosocial skills, implying a need to align educational focus with learning outcomes.

The data show a positive correlation between student satisfaction and skill proficiency in simulations, indicating that higher satisfaction is associated with greater proficiency in simulated tasks. Students reported that increased confidence and reliance were key to their improvement. However, in real patient interactions and communication, only moderate improvement was observed, aligning with findings in medical and pharmacy education.27

Specific skills like cordiality, relevant questioning, patient need analysis, active listening, and information gathering also showed moderate improvement. The link between self-efficacy and confidence28 suggests that enhanced confidence is crucial in the learning process. These findings resonate with Silberman et al.,29 affirming the importance of simulation in physiotherapy education.

The study highlights the importance of debriefing sessions in SBL, where students reflect on their experiences under expert guidance. Effective debriefing, led by knowledgeable instructors, is essential for developing clinical reasoning skills.30 Despite achieving learning objectives, students need further development in clinical skills like medical screening and patient interviews, emphasizing the need for ongoing education.

Our findings are in line with previous research, such as Sandoval-Cuellar et al.,31 demonstrating the effectiveness of simulation in teaching examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment in physiotherapy, particularly for low back pain. Additionally, simulation has been shown to enhance the understanding of roles and improve teamwork among nurse and physiotherapy students.

While simulation aligns with previous research, it is not definitive that it is the optimal tool for every clinical skill. It is important to compare various teaching methods and adapt them to diverse learning styles. The study's limitations include its case-study design and potential cultural biases. These factors could limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the lack of validated scales for measuring student satisfaction during the study is a limitation, though a reliable scale is now available.32

Despite these limitations, our findings advocate for the integration of SBL into physiotherapy curriculums, enhancing education in this field. Further research should evaluate SBL's effectiveness across various programs and include debriefing insights for a more comprehensive understanding of the learning experience.

This study underscores the importance of continuous skill development and ongoing education in physiotherapy. Future educational strategies should aim at closing gaps in clinical reasoning and patient management capabilities. Aligning with Sandoval-Cuellar et al.,31 our findings confirm the effectiveness of simulation-based learning (SBL) in training physiotherapy students, particularly in managing low back pain. This study not only highlighted improvements in examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment techniques but also noted the role of simulation in enhancing role comprehension and teamwork among nursing and physiotherapy students.

While the use of clinical simulation as a teaching method in physiotherapy is expanding, further research is needed, especially in areas like therapeutic interactions and clinical decision-making. It is essential to recognize that simulation, despite its proven benefits, may not be the ultimate tool for all clinical skills. The effectiveness of various teaching tools, methods, and strategies must be compared, considering the diverse learning styles of students. Understanding students’ backgrounds and learning preferences could offer insights to tailor clinical skill enhancement more effectively.

The study's design as a case study involving dual degree students in Human Nutrition and Physiotherapy might limit the generalizability of its findings. Moreover, cultural differences might influence the interpretation of SBL, as all study participants came from a similar cultural environment. Variations in course levels among students could also impact the results, necessitating consideration of different knowledge and skill levels.

At the time of this study, there were no validated scales for measuring student satisfaction, a limitation that has since been addressed with the introduction of a new reliability and validity scale.32 Additionally, the broad range of teaching styles and methodologies within simulation warrants caution when comparing studies under this umbrella.

Despite these limitations, our findings offer substantial evidence supporting the use of simulation in enhancing physiotherapy education. Higher education institutions can integrate SBL into their curricula to enrich student learning experiences. Future research should extend to evaluating SBL's effectiveness in various degree programs and incorporate debriefing insights for a more comprehensive understanding of the learning experience associated with SBL.

ConclusionsSimulation-based learning has proven to be an effective tool for facilitating the learning of the psychosocial model in physiotherapy, as it has been successful in developing a significant portion of the required skills. The positive outcomes observed in terms of skills acquisition are complemented by the high level of satisfaction reported by students. They perceive the simulation experiences as reliable, valuable, and applicable to their future professional roles.

However, further research is warranted to enhance the integration of evaluation and diagnosis skills in physiotherapy. Future studies could explore and evaluate specific strategies to effectively incorporate these skills into simulation-based learning, ensuring that students are adequately prepared to assess and diagnose patients in real-world clinical settings. By addressing this aspect, simulation-based learning can continue to evolve and better meet the educational needs of physiotherapy students.

Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the Faculty of nursing and physiotherapy at the Universitat de Lleida (UDL). Additionally, it has received approval from the CEIm (Ethics Committee for Research) at Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova with the code CEIC-2537. In accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (World Medical Association, 2013), student participation in the study was voluntary, and they had the option to decline participation in the simulation or refrain from sharing their experiences. All students were fully informed about the study and provided written informed consent.

FundingNo author of article had received any funding that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. None of the authors declare a conflict of interest.

Conflict of interestNone of the authors declare a conflict of interest.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work the authors used Chat GPT in order to improve grammatical language. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

We would like to thank all the participants in the study and the 4DHealth Innovation Simulation Center for collaborating in the simulation experience.