Diarrhoea is a common symptom after solid organ or haematopoietic transplant, with an incidence above 70%, generally in the first year post-transplant. It is most frequently caused by infectious colitis (especially due to cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Clostridium difficile [C. difficile] infection) and the immunosuppressants used to prevent rejection: mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), tacrolimus and cyclosporine. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease (CIBD) should form part of the differential diagnosis since, although rare, it has a higher incidence in transplant recipients than in the general population (206 vs 20 cases/100000 population/year), and is more common after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) than other solid organ transplants. Paradoxically, it develops in patients on pharmacological immunosuppression that is sufficient to prevent allograft rejection but not the onset of pre-existing or de novo CIBD.1,2

We present the case of a 71-year-old man with a personal history of: high blood pressure, persistent atrial fibrillation (permanent pacemaker and antiplatelet treatment with 150mg/day acetylsalicylic acid), IgA mesangial glomerulonephritis with moderate chronic renal failure (baseline creatinine clearance 37mL/min) and OLT in 1999 for cryptogenic liver cirrhosis, probably of autoimmune origin. Following the transplant, he started corticosteroid and cyclosporine treatment that was switched early on to tacrolimus and MMF due to deterioration of renal function and gingival hyperplasia. The patient did not develop any serious infections and continued combined treatment with tacrolimus and MMF until 2009, when the anti-calcineurin was discontinued due to nephrotoxicity.

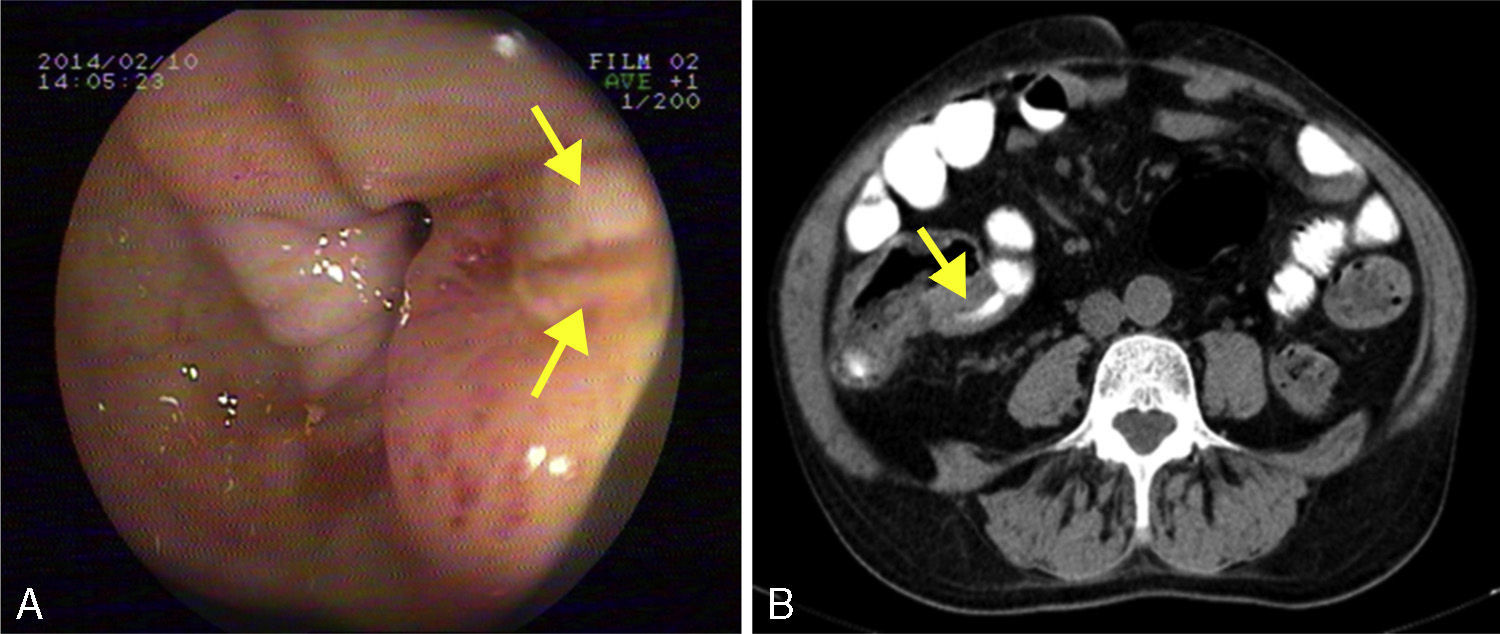

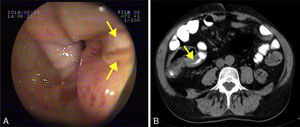

He was admitted to our hospital in 2014 for chronic diarrhoea with no mucous, blood or pus, accompanied by abdominal colic and constitutional syndrome, with unquantified weight loss. He was treated with 2g/day MMF. Baseline laboratory tests revealed: haemoglobin (Hb) 10.5g/dL (normocytic and normochromic), creatinine 2.1mg/dL, dissociated cholestasis with gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) 100 (ref. range 7–66U/L) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 199 (ref. range 40–129U/L); transaminases, total bilirubin and prothrombin activity were normal. Total protein was 5.1g/dL (albumin 2.4), and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 6.5mg/dL. Autoantibodies for coeliac disease (anti-gliadin and anti-transglutaminase) were negative, and IgA values were normal. Other organ-specific antibodies (ANA, AMA, anti-LKM, ASMA) were negative. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels were normal. Microbiological analysis of faeces (coproculture, parasitic examination and C. difficile toxin) found no abnormalities. Serology tests found: immunity against hepatitis B virus (HBV), CMV IgG positive, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) negative. Mantoux test and Booster effect were negative. Colonoscopy was initially performed, in which several longitudinal serpiginous ulcers were found in the right colon with deformity of the caecum and ileocaecal valve; it was impossible to intubate the terminal ileum (Fig. 1A). Chest-abdominal computed tomography (CT) found wall thickening of a 25-cm segment of terminal ileum, with no involvement of adjacent fat, free fluid, regional lymphadenopathies or pre-stenotic dilatation (Fig. 1B). Histopathology was consistent with an ulcer base, with no signs of specificity. Immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing performed on the samples ruled out CMV infection and tuberculosis, respectively. Finally, suspecting Crohn disease, intravenous corticosteroids were administered (0.8mg/kg/day methylprednisolone). After 10 days of treatment with no clinical response, the patient presented severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding with haemodynamic instability that required transfusion of 6 units of red cells. Oral endoscopy revealed numerous deep ulcers from the second part of the duodenum to close to the angle of Treitz, 1 of which had a visible vessel that was treated with a Hemoclip. Due to refractoriness to corticosteroids and extensive small bowel involvement, rescue treatment with azathioprine (50mg/day) and infliximab (5mg/kg) was proposed. After the first 2 induction doses, the patient did not present rebleeding, but eventually required surgical treatment for recurrent subocclusive episodes. Laparotomy found several short stenoses in the jejunum, and another 2 measuring around 15 and 25cm in length that caused pre-stenotic dilatation in the ileum. These were treated by segmental and ileocaecal resection with termino-terminal and latero-lateral anastomosis, respectively. Histopathology of the surgical specimen was consistent with Crohn disease. After a long postoperative period in intensive care due to cardiorespiratory and renal problems not attributable to complications of the surgery, the patient gradually improved and is currently in prolonged clinical and biological remission with 50mg/day azathioprine and 5mg/kg infliximab every 8 weeks, with no changes in liver function.

Fewer than 100 cases of de novo CIBD have been reported in liver transplant recipients to date (we are not aware of any previous cases in Spain), most of them ulcerative colitis (70%).3 This clear predominance of colitis could be explained by its strong association with primary sclerosing cholangitis, a disease that constitutes a common indication for liver transplant (6%–10% of the total).4

It has been suggested that the use of tacrolimus to prevent rejection could induce the onset of de novo CIBD.5 This drug, which is a potent interleukin-2 (IL-2) inhibitor, causes T-regulatory cell dysfunction that alters intestinal homeostasis, increasing intestinal permeability and exposure of antigens to the mucosal immune system. It also interferes in the process of programmed cell death of T-lymphocytes, making them more resistant to apoptosis, both considered to be major factors in the pathogenesis of CIBD. Furthermore, the development of CMV infection–especially in seronegative recipients from seropositive donors–also appears to be another risk factor for the development of de novo disease. Colonisation of the mucosa by the virus also increases intestinal permeability, expression of endothelial adhesion molecules type I (VCAM1), major histocompatibility complex type 1 and production of IL-6.

The prognosis for de novo CIBD is generally favourable, better than that for recurrence of previously diagnosed disease,6 and remission is usually achieved with conventional treatment (mesalazine, corticosteroids and azathioprine, a drug that is also effective in preventing rejection7). This was not the case in our patient, and we had to resort to anti-TNF treatment, and eventually surgery. In addition to the unusual nature of this disease, its form of presentation is also noteworthy, with extensive involvement of the proximal small intestine and the serious complication in the form of gastrointestinal bleeding. Although surgery could not be avoided, infliximab may have helped control the bleeding and improve the patient's general condition, so that elective surgery could be performed. We would like to stress that experience with anti-TNFs in transplant patients is scant; we are aware of only 22 cases reported to date for refractory disease, most treated with infliximab.8 Studies suggest that these drugs have a similar efficacy and safety profile when used in transplant recipients, although their short- and medium-term effect on the graft is unknown.9,10

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Tinoco R, García E, Ramírez F, Correro F, Vega V. Enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal de novo en paciente sometido a trasplante hepático por cirrosis criptogenética. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:458–460.