It has been proposed that primary care diagnose and treat hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. However, a care circuit between primary and specialized care based on electronic consultation (EC) can be just as efficient in the micro-elimination of HCV. It is proposed to study characteristics and predictive factors of continuity of care in a circuit between primary and specialized care.

MethodsFrom February/2018 to December/2019, all EC between primary and specialized care were evaluated and those due to HCV were identified. Variables for regression analysis and to identify predictors of completing the care cascade were recorded.

ResultsFrom 8098 EC, 138 were performed by 89 (29%) general practitioners over 118 patients (median 50.8 years; 74.6% men) and were related to HCV (1.9%). Ninety-two patients (78%) were diagnosed>6 months ago, and 26.3% met criteria for late presentation. Overall, 105 patients required assessment by the hepatologist, 82% (n=86) presented for the appointment, of which 67.6% (n=71) were viraemic, 98.6% of known. Finally, 61.9% (n=65) started treatment. Late-presenting status was identified as an independent predictor to complete the care cascade (OR 1.93, CI 1.71–1.99, p<0.001).

ConclusionCommunication pathway between Primary and Specialized Care based on EC is effective in avoiding significant losses of viraemic patients. However, the referral rate is very low, high in late-stage diagnoses, heterogeneous, and low in new diagnoses. Therefore, early detection strategies for HCV infection in primary care are urgently needed.

Se ha propuesto que atención primaria diagnostique y trate la infección por virus de la hepatitis C (VHC). Sin embargo, un circuito asistencial entre atención primaria y especializada basado en la consulta electrónica (CE) puede ser igual de eficiente en la microeliminación del VHC. Se propone estudiar características y factores predictivos de la continuidad asistencial en un circuito entre atención primaria y especializada.

MétodosDesde febrero/2018 y diciembre/2019 se evaluaron todas las CE entre atención primaria y especializada, y se identificaron aquellas por VHC. Se registraron variables para análisis de regresión e identificar factores predictores de completar cascada de atención.

ResultadosDe un total de 8.098 CE, 138 realizadas por 89 (29%) médicos generales de 118 pacientes (mediana de 50,8 años; 74,6% varones) fueron por VHC (1,9%). Noventa y dos pacientes (78%) fueron diagnosticados hace más de 6 meses), y el 26,3% cumplía criterios de presentación tardía. En total, 105 pacientes requirieron valoración por el hepatólogo. El 82% (n=86) se presentaron a la cita, de los cuales el 67,6% (n=71) eran virémicos, el 98,6% de los conocidos. Finalmente, el 61,9% (n=65) inició tratamiento. El estado de presentación tardía se identificó como un factor predictivo independiente para completar la cascada de atención (OR: 1,93; IC 95%: 1,71-1,99; p<0,001).

ConclusiónLa comunicación entre atención primaria y especializada basada en la CE es eficaz para evitar pérdidas significativas de pacientes virémicos. Sin embargo, la tasa de derivación es muy baja, elevada en diagnósticos en fase tardía, heterogénea y escasa en nuevos diagnósticos. Por tanto, se necesitan con urgencia, estrategias de detección precoz de infección por VHC en atención primaria.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a global health problem and one of the leading causes of chronic liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide.1 Direct-acting antivirals have shown high rates of sustained viral response, and a strong impact on the prevalence of HCV infection, the progression of liver fibrosis, and late presentation.2 For this reason, the World Health Organisation has set global targets for HCV elimination as a public health threat by 2030. These goals include a reduction of new infections by 90%, a reduction of liver-related mortality by 65%, and treating 80% of treatment-eligible individuals.3

A conceptual framework to establish efficient HCV micro-elimination tasks has been created. The strategies are centred on harm-reduction programmes and screening policies, removing treatment restrictions, linkage-to-care circuits, diagnosis, and awareness of HCV status.4,5 For instance, in our health care area, care for high-risk populations for HCV infection, such as patients attended to at drug addiction centres, has been approached by facilitating diagnoses by dried blood spot testing and linkage to care by telemedicine6 and in those lost to follow-up, by increased HCV awareness and improved referral by implementing electronic alerts in medical records.7,8

Another strategy, such as treating patients in primary care (PC) settings or a task-shifting of care to non-specialists, has been proposed because a decentralized and multidisciplinary care approach may be essential to improving access to testing, linkage-to-care, and treatment.9 PC is the gatekeeper, and most cases of undiagnosed HCV infection or patients lost to follow-up are attended to by general practitioners; therefore, it has been suggested that PC should be enabled to not just diagnose, but to treat patients to avoid losses in the cascade of care.10 However, although this strategy could reduce the number of steps to initiating treatment, the need for additional education and training in HCV management, inadequate reimbursement in some scenarios, overload in care, time commitment and complexity of some patients may make it difficult to use this strategy in all settings.11

Alternatively, care circuits between PC and specialized care have been established based on telehealth to simplify the pathway. Electronic consultation (EC) or e-consult, also called remote or virtual consult, is a pathway based on a computer tool integrated into the health system affording general practitioners direct, asynchronous, and interdisciplinary communication.12,13 It has proven to be effective in reducing consultations, unnecessary procedures, costs, and waiting time in different fields.14 However, its effectiveness in micro-elimination tasks, specifically in the HCV cascade and continuum of care, is unknown. Thus, this study aimed to assess the efficacy and predictive factors of drop-outs in the HCV cascade of care in a care circuit between PC and specialized care based on EC.

Patients and methodsStudy designSince 2012, primary care physicians established contact with gastroenterologists by texting the reason in a free text box within the electronic medical platform that includes PC and specialized care for this purpose. A reply by the specialist is expected before 48h. The specialist may then ask for more information, discharge the patient, or schedule an appointment for further evaluation.

We retrospectively evaluated the total contacts by EC between 54 PC centres and the Gastroenterology Department of the Hospital Universitario de Canarias from February 1st, 2018 to December 31st, 2019.

From the electronic medical record system, we manually reviewed and identified ECs related to HCV infection, that is, where there was a request by the general practitioner for evaluation based on a positive hepatitis C antibody test or a positive RNA test. The reflex HCV RNA testing was implemented at July 2018 in our system.

After excluding deaths, duplicated cases, or those with incomplete information, we registered the age, sex, nationality, tobacco, alcohol, previous history of human immunodeficiency virus serology or hepatitis B, obesity, arterial hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidaemia status of the patients. Regarding HCV infection, we registered the risk factors for HCV infection, liver-related complications (clinical ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, hepatocarcinoma, jaundice), date of first and subsequent HCV serology requests, date of RNA request and result, identity of primary care physician and primary health care centre, additional specific reason for referral (abnormal liver function tests, high viral load, presence of symptoms, signs of chronic liver disease), presentation for the referral appointment, prescription of HCV treatment in patients with detectable RNA and sustained virological response assessment.

We additionally registered Fibroscan (Echosens, France) value if available and calculated biomarkers of liver fibrosis (FIB-4 score, APRI, Forns index) of patients at the time of EC contact based on alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, platelet levels, total cholesterol, and gamma-glutamyl transferase. We used previously validated cut-off values of serological fibrosis markers to stage fibrosis,15 and stage≥F3 (APRI≥1.5, FIB-4≥3.25, Fibroscan≥9.5kPa) was considered late presentation or advanced fibrosis. Stage F2 (APRI≥0.5, FIB-4≥1.45, Fibroscan≥7.0kPa) was considered significant fibrosis. Stage F4 or cirrhosis was defined by a Fibroscan value≥12.5kPa.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were expressed with absolute frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed with means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges. The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables and Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Independent predictors for attending the appointment were estimated using logistic regression. p values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used SPSS 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, Version 25.0. Armonk, New York: IBM Corp.) for statistical analysis.

Ethical aspectsThe study was conducted following the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration of October 2013. Data were handled confidentially in an encrypted database that could only be accessed by the involved researchers, under the current law (Organic Law of Protection of Personal Data 03/2018). Ethical approval was obtained on 26th December 2018 by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario de Canarias and by the Ethical Committee of Primary Care Management. Both committees knew about the study's ethical, legal and methodological aspects and the informed consent was waived by ethical committee.

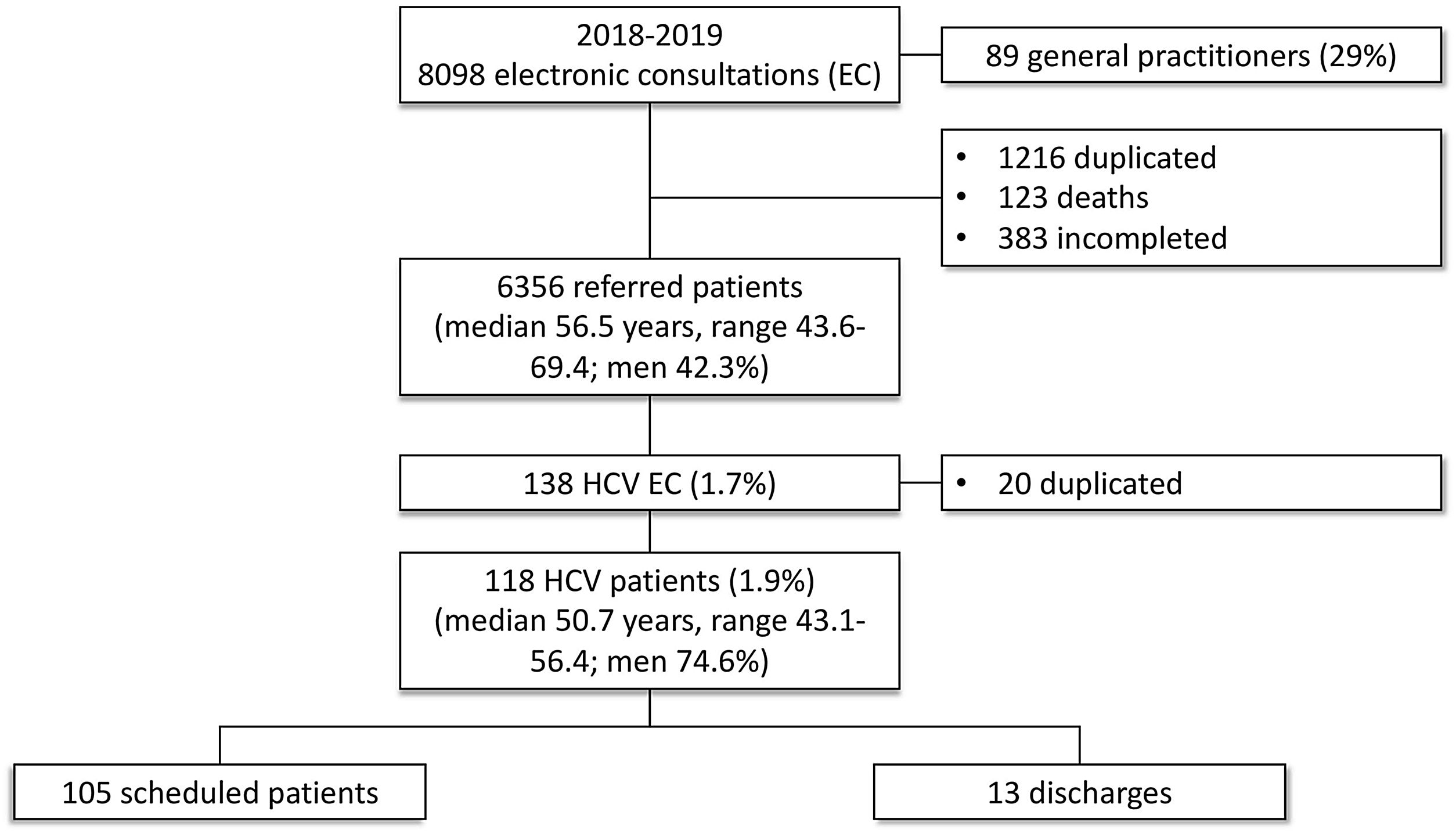

ResultsCharacteristics of patientsDuring the study period, we registered 8098 EC of 6356 patients (median age, 56.5; range 43.6–69.4 years; men 42.3%). After excluding deaths (n=123) and cases with duplicated EC (n=1216) and incomplete information (n=383), 138 contacts (20 EC were repeated) by EC for 118 patients (median age, 50.7; range 43.1–56.4 years; men 74.6%) were related to HCV (1.9%). The EC were performed by 89 out of 306 (29%) general practitioners (Fig. 1).

In particular, the presence of a positive anti-HCV test without symptoms was the reason for contact in 109 patients (92.4%), of which only 23 (21.1%) were newly diagnosed with HCV infection. In this group of asymptomatic patients, the majority of contacts asked to return for follow-up (35.7%), requested evaluation after being newly diagnosed with HCV infection (27.5%), had abnormal transaminases (25.6%), and in a minority (10.2%) the reason was a pathological imaging test, asking for sustained virological response status or a positive RNA-HCV test. Nine patients showed symptomatic disease related to complications of chronic HCV infection.

All 118 referred patients had a positive anti-HCV test, but only 22% (n=26) were newly diagnosed (<6 months) with HCV infection (median 10.1, range 6–20.7 days). The remaining 78% (n=92) had a positive anti-HCV test result long before the EC (median 9.26, range 5.68–12.86 years). A positive HCV RNA result was available for 51 patients (43.2%) and HCV RNA was requested for another 33 patients, been the rest RNA negative. Overall, 71 patients (60.2%) tested positive (median time after antibody HCV positive, 7.73 months; range 0.3–82.8). In our cohort, 31 patients (26.3%) showed late presentation at the moment of the referral. Table 1 shows the characteristics of included patients.

Characteristics of patients referred by electronic consultation related to hepatitis C virus (n=118).

| Age (years) (median, IQR) | 51 (43.1–56.4) |

| Sex (male) (n,%) | 88 (74.6%) |

| Nationality | |

| EU citizen | 108 (91.5%) |

| APRI (mean, 95% CI) | 0.8 (0.5–1.0) |

| FIB-4 | 1.8 (1.41–2.13) |

| Forns index | 5.0 (4.6–5.3) |

| Dyslipidemia | 15 (12.7%) |

| Obesity (BMI>30) | 15 (12.7%) |

| Hypertension | 30 (25.4%) |

| Type 2 Diabetes mellitus | 11 (9.3%) |

| Alcohol consumption | 58 (49.1%) |

| Smoking | 69 (58.5%) |

| Mental health issue | 27 (22.9%) |

| Fibroscana(kPa) (mean, 95% CI) | 8.1 (6.2–10.1) |

| iQRa(%) | 12.8 (10.6–15.1) |

| ALT (UI/L) (median, IQR) | 44 (20–80) |

| AST (UI/L) | 34 (22–54) |

| GGT (UI/L) | 37 (22–89) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 175 (147–202) |

| Platelet count (×103mm3) | 231 (189–275) |

| Prior follow-up & Department | 77 (65.3%) |

| Gastroenterology | 44 (37.3%) |

| Internal Medicine | 7 (5.9%) |

| Infectious Disease | 6 (5.1%) |

| HDTU | 3 (2.5%) |

| Addiction Care Centre | 2 (1.7%) |

| Others | 14 (11.9%) |

| Liver complications | 22 (18.6%) |

| Cirrhosis | 14 (11.9%) |

| Jaundice | 2 (1.7%) |

| Variceal bleeding | 2 (1.7%) |

| HCC | 2 (1.7%) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1 (0.8%) |

| Ascites | 1 (0.8%) |

| Active coinfections | 5 (4.2%) |

| HBV | 4 (3.4%) |

| HDV | 1 (0.8%) |

| Significant fibrosis or worse (≥F2) | 73 (61.9%) |

| Late presentation (≥F3) | 31 (26.3%) |

| Liver cirrhosis (F4) | 21 (17.8%) |

ALT: alanine transaminase; APRI: aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; AST: aspartate transaminase; BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; EU: European union; FIB-4: fibrosis-4; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCC: hepatocarcinoma; HDTU: Hospital Detoxification Treatment Unit; HDV: hepatitis D virus; IQR: interquartile range; n: number of patients.

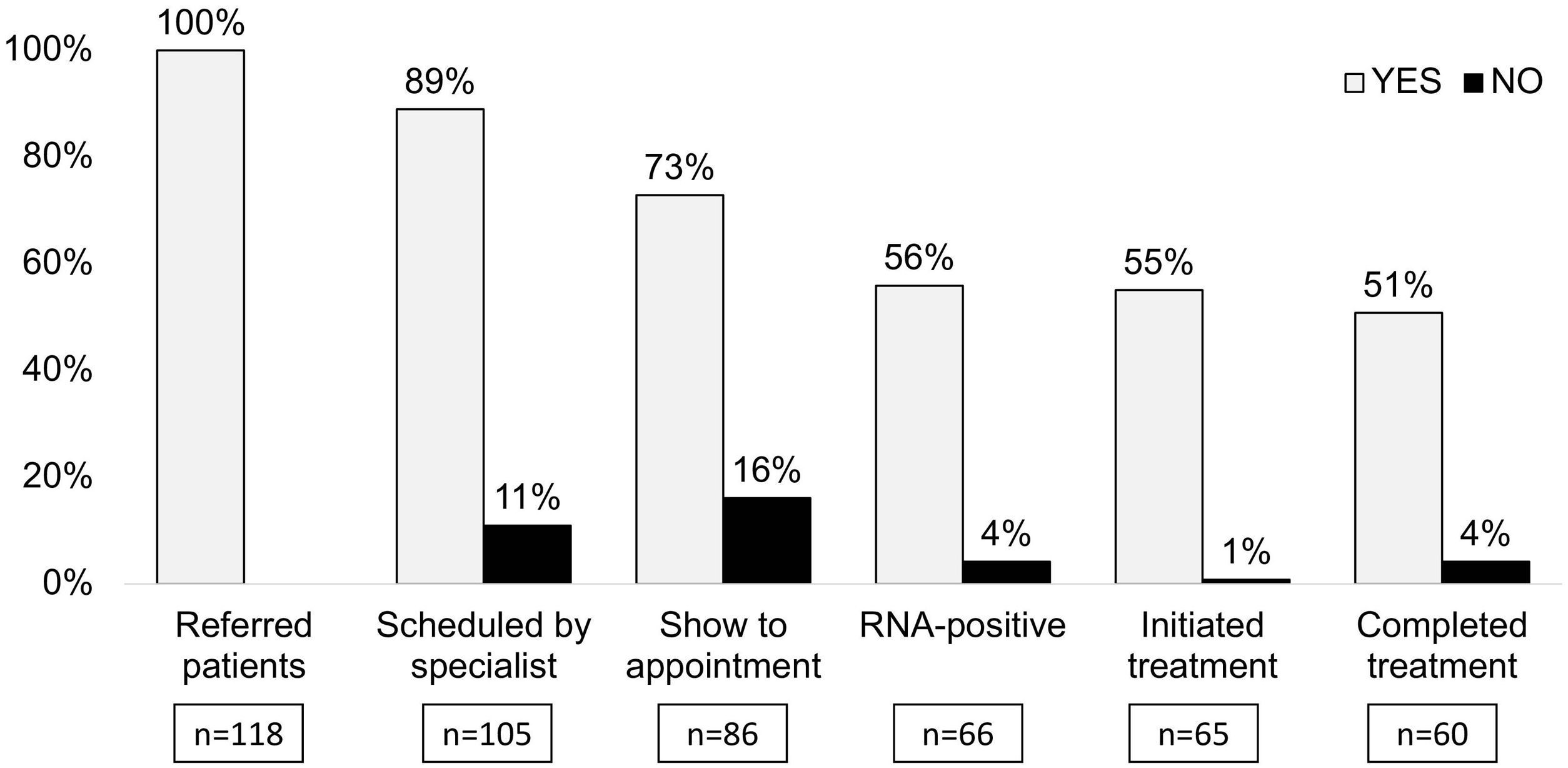

Fig. 2 shows the cascade of care for the 118 referred patients. One hundred and five (89%) patients required assessment by a specialist, and 13 (11.9%) did not need further assistance due to undetectable RNA (n=9), being on follow-up (n=3), and negative anti-HCV test (n=1). Among the 105 patients scheduled for an appointment with the hepatologist, 86 (82%) presented for the appointment, 66 (62.8%) were prescribed direct-acting antiviral therapy, 65 (61.9%) initiated treatment, and 60 (57.1%) completed treatment. All the patients evaluated achieved sustained virological response, and 11 patients were not available for sustained virological response assessment.

Concerning the cascade of care for viraemic patients, 93% of viraemic patients presented for the appointment (66 of 71), 91.5% initiated treatment (65 of 71; in one pregnant patient, treatment was postponed until after delivery), and 84.5% completed treatment (60 of 71), that is, 98.4% of viraemic patients who were present for the appointment with the hepatologist initiated treatment (65 of 66). Only five viraemic patients were not present for the appointment, and four patients remained without treatment 2.6 years after the EC contact. Two of them were referred to the specialist by EC again, but only one was present for the appointment and completed treatment.

Patients’ adherence to appointments and characteristicsTable 2 shows characteristics of patients who attended the appointment compared with those of patients who did not attend the appointment with the hepatologist. Patients who were present for the appointment had older ages (52.3 vs 44.4; p<0.005), higher rate of active infection (76.7% vs 26.3%; p<0.001) and late presentation (31.4% vs 15.8%; p<0.001). However, in the logistic regression analysis only having a late presentation was an independent predictor of being present for the appointment (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.71–1.99; p<0.001) (Table 3).

Characteristics of patients regarding attendance to the appointment.

| Present for appointment (n=86) | Absent for appointment (n=19) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (median, IQR) | 52.4 (49.8–55) | 44.4 (39.7–49.1) | 0.005 |

| Sex (male) | 63 (73.3%) | 16 (84.2%) | 0.317 |

| Risk factors | 48 (40.7%) | 11 (68.7%) | 0.834 |

| Parenteral drugs | 27 (32.1%) | 8 (42.1%) | |

| Tattoos | 7 (8.3%) | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Risky sexual practice | 5 (6%) | ||

| Blood transfusion before the 90s | 5 (6%) | 1 (5%) | |

| Orthodontics | 3 (4%) | ||

| Arterial/venous catheter | 1 (1%) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 46 (53.5%) | 9 (56.3%) | 0.629 |

| Smoking | 52 (60.5%) | 14 (87.5%) | 0.280 |

| Reason for referral | 0.072 | ||

| Returning for follow-up | 27 (31.4%) | 8 (42.1%) | |

| Hypertransaminasemia | 25 (29.1%) | 3 (15.8%) | |

| New HCV diagnosis | 17 (19.8%) | 8 (42.1%) | |

| Symptomatic | 8 (9.3%) | ||

| Other | 9 (10.5%) | ||

| Prior follow-up (n, %) | 56 (65.1%) | 12 (63.2%) | 0.872 |

| Previously requested RNA | 55 (63.9%) | 12 (63.2%) | 0.948 |

| Viraemic patients | 66 (76.7%) | 5 (26.3%) | <0.001 |

| Timing of first anti-HCV (months) | 89.0 (74–104.1) | 71.1 (31.5–110.6) | 0.336 |

| Timing of first RNA | 36.1 (19.4–52.9) | 77.2 (22.5–131.9) | 0.812 |

| Timing of last follow-up | 74.5 (54.5–94.6) | 98 (40.7–155.3) | 0.366 |

| ALT (UI/L) (median, IQR) | 73 (56–90) | 76(37–115) | 0.887 |

| AST (UI/L) (median, IQR) | 59 (45–74) | 114.2 (15–244) | 0.095 |

| GGT (UI/L) (median, IQR) | 83 (57–111) | 71 (31–111) | 0.689 |

| APRI score | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 1.0 (0.1–1.8) | 0.630 |

| FIB-4 | 1.9 (1.4–2.3) | 1.7 (0.9–2.5) | 0.760 |

| Forns index | 5.2 (4.8–5.6) | 3.8 (2.9–4.8) | 0.015 |

| Significant fibrosis or worse (≥F2) | 59 (68.6%) | 10 (52.6%) | 0.184 |

| Late presentation (≥F3) | 27 (31.4%) | 3 (15.8%) | <0.001 |

| Liver cirrhosis (F4) | 17 (19.8%) | 3 (15.8%) | 0.689 |

ALT: alanine transaminase; Anti-HCV: hepatitis C antibodies; APRI: aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; AST: aspartate transaminase; FIB-4: fibrosis-4; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; HCV: hepatitis C virus; IQR: interquartile range; n: number of patients; RNA: ribonucleic acid.

Independent predictors for missed appointments in multiple binary logistic regression analysis.

| n=105 | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male vs female) | 3.68 | (0.66–20.4) | 0.136 |

| Age≥52 years (yes vs no) | 2.57 | (0.59–11.3) | 0.211 |

| New diagnosed HCV infection (no vs yes) | 0.41 | (0.07–2.57) | 0.342 |

| Known viraemia before EC (yes vs no) | 2.19 | (0.54–8.89) | 0.272 |

| Abnormal liver function tests (no vs yes) | 0.66 | (0.17–2.65) | 0.559 |

| Prior follow (no vs yes) | 0.75 | (0.13–4.26) | 0.749 |

| Late presentation (yes vs no) | 1.93 | (1.71–1.99) | <0.001 |

| Parenteral drugs users (yes vs no) | 1.01 | (0.25–4.08) | 0.991 |

CI: confidence interval; EC, electronic consultation; HCV, hepatitis C virus; OR: odds ratio.

Our study shows that a significant proportion of HCV viraemic patients referred from PC to specialized care after establishing contact through EC were successfully linked to care without substantial losses along the cascade of care. Furthermore, EC allows for relinking of patients who were lost to follow-up as the majority of patients were long diagnosed before the referral.

Despite the desire to eliminate HCV by 2030, it would only be a reality if screening efforts are associated with linkage strategies with provision of broad and full access to antiviral therapies.16 In this matter, some authors identify PC to be a unique setting for an expanded role in HCV treatment and the implementation of linkage-to-care programmes.17 Several studies have shown that decentralization and a simplified model in PC independently of specialists could reduce gaps and barriers in the health system.18 In addition, HCV treatment administered by general practitioners is as safe and effective as that provided by hepatologists.19 Alternatively, a co-localized approach with shared responsibilities to improve hepatitis C cascade of care has been proposed.20 However, these studies still point out significant attrition rates along the cascade of care and a need for a consolidated structure between levels of health care to improve linkage to care.11,15

The communication pathway between PC and specialized care in our health care area is based on asynchronous EC. It represents an effective tool for improving access to specialists, reducing waiting time, reducing inappropriate in-person visits, lowering burden on limited health system resources, time and costs to patients and providers.21 It also has an advantage compared to other telehealth resources of teleconsultation being asynchronous, which facilitates the communication between levels of care and optimizes time.22

Our results argue for maintaining the current pathway based on EC as most of the viraemic patients in need of treatment were successfully evaluated by the hepatologist. Thus, our data does not support the need for task-shifting from specialized to PC at least concerning treatment to accomplish HCV micro-elimination.

The 18% no-show rate in our study is in keeping with the average no-show rate across studies evaluating the attendance of patients to scheduled appointments.23 Some studies argue that the most frequently reported causes of missed appointments by patients are family commitments, forgetting the appointment, and transportation difficulties. It is known that missed appointments are associated with existing prior follow-up or comorbid conditions including mental health issues or history of substance abuse, such as tobacco or alcohol abuse.24 However, this was not the case in our cohort of patients where not having a late presentation was the only factor associated with not being present for the appointment.

Previous studies have shown that over 50–75% of screened patients are unaware of their HCV RNA status.25 In a recently published paper by our group, we found PC testing request to be a predictor of non-RNA request after testing positive for HCV antibodies.26 In our cohort, 71% of patients were tested for HCV RNA before the EC (43.2% positive) and this increased to 91% (59.3% positive) after the EC, increasing the proportion of viraemic patients by 16.1%. Overall, only five viraemic patients were not linked to care, and so 93% of viraemic patients underwent specialized care assessment. We considered these figures difficult to improve,27 though we have to take into account that seven patients who were not present for appointments did not have RNA requests, which may have led to an overestimation of our optimistic results.

As expected, our findings show that 92% of patients who initiated direct-acting antiviral therapy completed the full prescribed course of treatment, although 25% of viraemic patients with completed treatment were absent from the appointment for checking for sustained virological response.28

Interestingly, only 24.8% of general practitioners referred patients infected with HCV during the study period, which was less than expected. The lack of awareness of HCV among PC physicians may account for this. In this regard, media campaigns, deployment of resources to increase HCV testing, and interdisciplinary meetings should be planned to improve referrals.8,29 In addition, although appropriate clinical care pathways and referral systems are needed, we also considered the need for improvement in strategies for screening as only 20% of patients were newly diagnosed with HCV infection.28

Our study has certain limitations. First, the socioeconomic status and relationship with being absent from appointments could not be considered due to our retrospective design. Second, we considered that urban-rural disparities may account for the no-show rate,30 however, these differences are not so evident in our setting. Third, we considered that number of EC could be decreased after the implementation of reflex HCV RNA testing.

In conclusion, contact between PC and specialized care by EC is effective for referring viraemic patients without significant losses in the cascade of care. Nevertheless, the referral of patients with HCV infection has a low rate, is heterogeneous, deficient in new diagnoses, and late as almost a third of patients are at risk of late presentation. Therefore, policy plans and screening strategies in PC setting are urgently needed to accomplish timely HCV elimination plans.

FundingThis study was supported in part by grants from Fondos FEDER. Dr. M. Hernández-Guerra is the recipient of a Grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI19/01756).

Conflict of interestDr. M. Hernández-Guerra has received research grants from AbbVie and Gilead. Dr. D. Morales-Arráez has received a research grant from Gilead sponsored by the Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver (AEEH). All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We thank BIOAVANCE and CIBICAN for their editorial support.