The Strategic Plan for Tackling Hepatitis C launched in 2015 in Spain has led to an important nationwide decrease in hepatitis C related hospitalisation rates. However, patients’ infection progression during decades could increase their health status complexity and challenge patient's prognosis after hepatitis C eradication.

MethodsWe carried out an observational retrospective study evaluating the prevalence of the main co-infections, comorbidities (risk factors and extrahepatic manifestations), and alcohol or other substances abuses in chronic hepatitis C related hospitalised patients in Spain. Data were obtained from the National Hospitalisation Registry discharges from January 1st of 2012 to December 31st of 2019.

ResultsBetween 2012 and 2019 there were 356,197 chronic hepatitis C-related hospitalisations. In-hospital deaths occurred in 11,558 (4.6%) non-advanced liver disease and in 10,873 (10.4%) advanced liver disease-related hospitalisations.

Compared to 2012–2015, in 2016–2019 the proportion of hospitalisations related to non-advanced liver disease increased from 69.4% to 72.4%, while the advanced disease-related hospitalisations decreased from 30.6% to 27.6% (P<.001). In spite of the decrease in severe cases among hospitalisations, all comorbidities evaluated, and alcohol abuse increased in 2016–2019 compared to 2012–2015, while co-infections and other substances abuses decreased in the same period.

In the latest period (2016–2019): 28,679 (18.3%) of the hospitalised patients had a HIV, 6928 (4.4%) a hepatitis B, and 972 (.6%) a tuberculosis co-infection. Most frequent comorbidities were diabetes (N=33,622; 21.5%); moderate to severe renal disease (N=28,042; 17.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma (N=25,559; 16.3%), and malignant neoplasms (excluding hepatocellular carcinoma) (N=19,873; 12.7%). Alcohol or substances abuse was reported in 48,506 (31.0%) hospitalisations: 30,782 (19.7%) with alcohol; 29,388 (18.8%) with other substances; and 11,664 (7.5%) with both, alcohol and other substances, abuses.

ConclusionsDespite the reduction in advanced liver disease hepatitis C-related hospitalisations due to prioritisation of treatment to the more severe cases, high and increasing prevalence of comorbidities and risks factors among hepatitis C-related hospitalisations have been found.

El Plan Estratégico para el Abordaje de la Hepatitis C lanzado en España en 2015ha supuesto una importante disminución a nivel nacional de las tasas de hospitalización relacionadas con la hepatitis C. Sin embargo, la progresión de la infección en los pacientes durante décadas podría aumentar la complejidad de su estado de salud y desafiar el pronóstico del paciente después de la erradicación de la hepatitis C.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio observacional retrospectivo evaluando la prevalencia de las principales coinfecciones, comorbilidades (factores de riesgo y manifestaciones extrahepáticas) y abuso de alcohol u otras sustancias en pacientes hospitalizados relacionados con hepatitis C crónica en España. Los datos se obtuvieron del Registro de altas hospitalarias entre el 1 de enero de 2012 y el 31 de diciembre de 2019.

ResultadosEntre 2012 y 2019 hubo 356.197 hospitalizaciones relacionadas con hepatitis C crónica y se registraron 11.558 (4,6%) muertes intrahospitalarias relacionadas con hospitalizaciones por enfermedad hepática no avanzada y 10.873 (10,4%) por enfermedad hepática avanzada.

En comparación con 2012-2015, en 2016-2019 la proporción de hospitalizaciones relacionadas con enfermedad no avanzada aumentó del 69,4% al 72,4%, mientras que las relacionadas con enfermedad avanzada disminuyeron del 30,6% al 27,6% (P <0,001). A pesar de la disminución de casos graves entre las hospitalizaciones, todas las comorbilidades evaluadas y el abuso de alcohol aumentaron en 2016-2019 en comparación con 2012-2015, mientras que las coinfecciones y el abuso de otras sustancias disminuyeron en el mismo período.

En el último período (2016-2019): 28.679 (18,3%) de los pacientes hospitalizados tenían VIH, 6928 (4,4%) hepatitis B y 972 (0,6%) coinfección tuberculosa. Las comorbilidades más frecuentes fueron diabetes (N=33.622; 21,5%); enfermedad renal moderada a grave (N=28.042; 17,9%), enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica y asma (N=25.559; 16,3%) y neoplasias malignas (excluyendo el carcinoma hepatocelular) (N=19.873; 12,7%). El abuso de alcohol o sustancias se notificó en 48.506 (31,0%) hospitalizaciones: 30.782 (19,7%) con abuso de alcohol; 29.388 (18,8%) de otras sustancias; y 11.664 (7,5%) con ambos, alcohol y otras sustancias.

ConclusionesA pesar de la reducción de las hospitalizaciones por hepatitis C con enfermedad hepática avanzada debido a la priorización del tratamiento en los casos más graves, se ha encontrado una alta y creciente prevalencia de comorbilidades y factores de riesgo entre las hospitalizaciones por hepatitis C.

The Spanish Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare launched in 2015 the Strategic Plan for Tackling Hepatitis C in the Spanish National Health System (hereinafter Strategic Plan).1

The Strategic Plan provided guidance for hepatitis C virus (HCV) direct acting antiviral treatment implementation nationwide, giving priority to those patients with HCV with more severe liver disease patterns. Consequently, chronic HCV-related hospitalisation rates trend in Spain changed, from an increasing trend in the hospitalisation rates up to 20142,3 to a decrease of 26% in the hospitalisation rates in 2018 compared to 2014 (from 111.8 in 2014 to 83.0 in 2018 hospitalisations per 100,000 population).4,5

In spite of the promising results, HCV infection has been demonstrated to result in several adverse hepatic outcomes and has been associated with a number of important extrahepatic manifestations.6–9 Moreover, some studies suggest that, although eradication of HCV is associated with cirrhosis regression or ‘freezing’, there may be a point of no return in tissue damage for patients with advanced liver disease (AdLD).10–12 Therefore, it would be relevant to know more about the comorbidities and clinical complexity of chronic hepatitis C patients requiring hospitalisation in Spain that could influence or challenge patient's prognosis after HCV eradication.

There are so many hepatic and extrahepatic factors related to HCV progression that have been described in previous studies, as coinfections,13,14 diabetes,15–17 and hepatocarcinoma (HCC)18 or other extrahepatic malignancies.19,20 Additionally, other factors as alcohol and other substances abuses are related not only with worsening of the course of liver disease,21 but it also can impact negatively after sustained virological response increasing the risk of re-infections.22

Therefore, the main objective of this study is to evaluate the presence of the main co-infections, comorbidities (risk factors and extrahepatic manifestations), and alcohol or other substances abuses in chronic hepatitis C related hospitalised patients in Spain by the severity of the disease. For that purpose, HCV patients with advanced (with decompensated cirrhosis, HCC or liver transplant) vs. non-advanced (no hepatic signs or compensated cirrhosis) liver disease were compared. As a secondary objective, changes in the presence of those comorbidities and risk factors for worse prognosis of the disease would be assessed by pre-treatment (2012–2015) and treatment (2016–2019) implementation periods.

MethodsWe carried out an observational retrospective study. The study population consisted of patients discharged from Spanish hospitals with chronic hepatitis C related hospitalisations from January 1st of 2012 to December 31st of 2019.

Data source and collectionChronic HCV-related hospitalisations were obtained from the National Registry of Hospitalisations of the Ministry of Health. This registry compiles a Minimum Basic Data Set (MBDS) using the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9) till the end of 2015 and the 10th revision (ICD-10) from 2016 onwards. The MBDS includes information on sex, age, date of birth, date of admission and date of discharge, outcomes and hospital related costs. This registry collects up to 20 diagnoses related to the hospitalisation (One Main and 13 Secondary Diagnoses before 2016, and 1 Main and 19 Secondary Diagnoses from 2016 and onwards) and up to 20 medical procedures. We selected all hospitalisation discharges with chronic hepatitis C ICD codes in any of the diagnoses:

- •

Hepatitis C ICD-9 codes (2014–2015): 070.44, 070.54, 070.7, 070.70, 070.71, and V02.62.

- •

Hepatitis C ICD-10 codes (2016–2018): B18.2, B19.2, B19.20, B19.21, and Z22.52 (temporary code for hepatitis C carriers for 2016 and 2017).

AdLD was defined as those hospitalised patients with at least one diagnosis code for chronic HCV (including unspecified hepatitis C and ICD-9/temporal ICD-10 for carriers) with a second diagnosis code for decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, or liver transplant. AdLD definition was performed as in previous published works4,5,23 and it is shown in Annex 1.

Hospitalisations were classified as non-AdLD (N-AdLD) when chronic HCV with no coma specific codes were used for ICD-9 (070.54, 070.7, 070.70 or V02.62) or ICD-10 (B18.2, B19.2, B19.20, or Z22.52) and the patient did not present any other diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis (including a separate/later diagnosed coma during the hospitalisation code), HCC or liver transplant.

To evaluate symptoms, comorbidities and risk factors related to worse prognosis, we reviewed those reported in previous literature. Diagnoses and their correspondent ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes identified in other manuscripts and used for this analysis are described in Annex 2.

Statistical analysisWe calculated the hospitalisations absolute number and distribution percentages for: all chronic HCV-related; AdLD and N-AdLD hospitalised patients; and by severity status (with no signs of hepatitis disease, with compensated cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, HCC, or liver transplant).

Numbers and percentages of in-hospital deaths, co-infections, comorbidities, and alcohol or other drugs abuses were calculated for all chronic HCV-related hospitalisations, AdLD and N-AdLD groups, and by severity.

Due to the implementation of the strategic plan in 2015 in Spain and the overlapping adaptation to ICD-10 in 2016, we created two different periods to compare: period 2012–2015 (before the effects of the Strategic Plan), and period 2016–2019 (after the Strategic Plan).

For comparison of means, we used the t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum text when non-normal distribution of the data was observed. Proportions were compared using the chi-square test.

Statistical significance was set at P<.05. All analyses were performed using Stata version 12.

ResultsDemographic characteristics of chronic HCV-related hospitalised patients in Spain (2012–2019 period)Between 2012 and 2019 there were 356,179 chronic HCV-related hospitalisations: 252,041 (70.8%) due to N-AdLD hospitalised patients and 104,138 (29.2%) due to AdLD hospitalised patients.

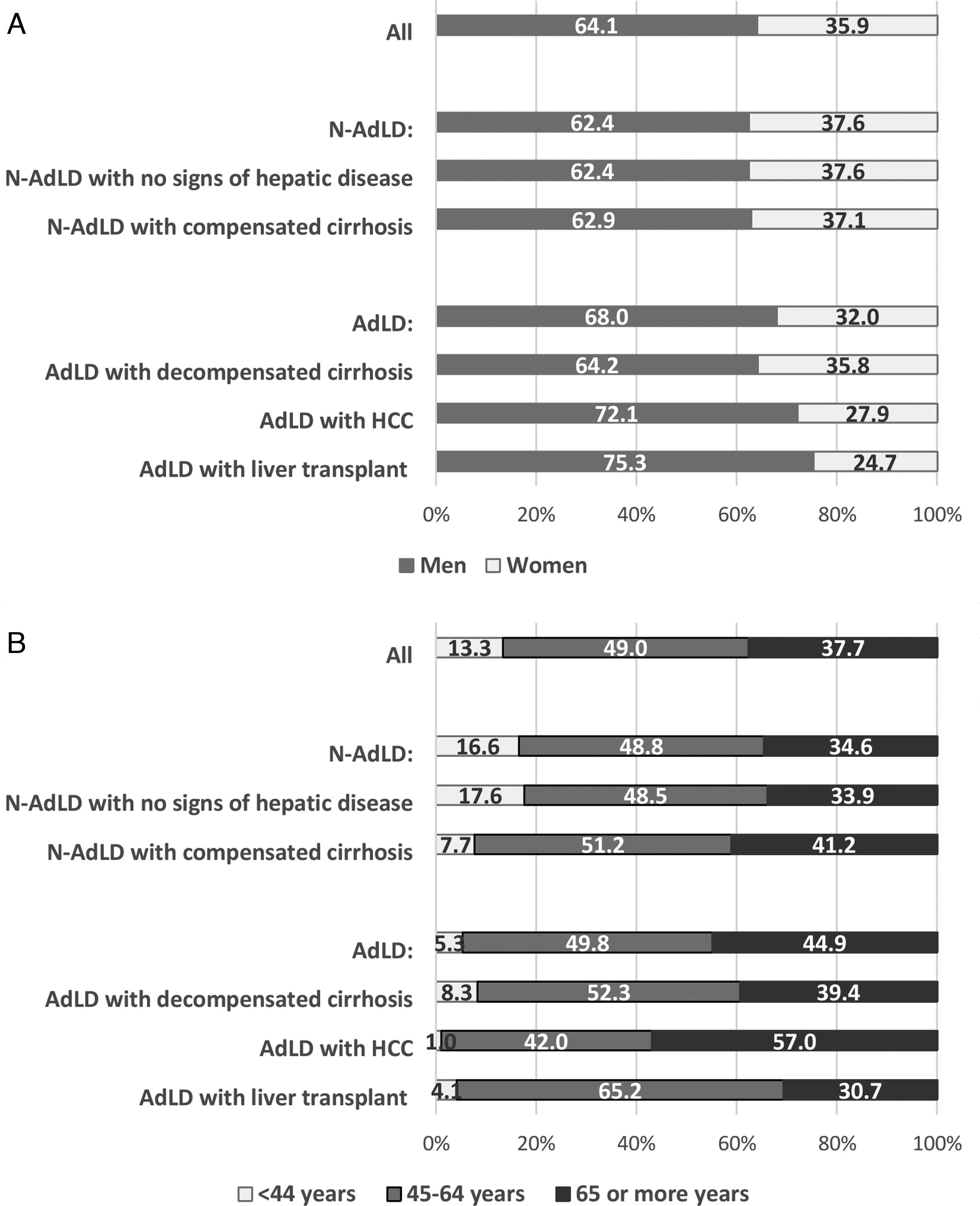

Overall, 228,186 (64.1%) hospitalised patients were males and 127,977 (35.9%) females. Differences between sexes distribution were more marked (with higher proportion of males affected) in HCC and liver transplant (Fig. 1a). The proportion of males compared to females for HCC was 72.1% vs. 27.9%, and 75.3% vs. 24.7% for liver transplant (In both cases P-value were <.001 when compared to the overall by sex distribution).

Most of the hospitalisations were related to patients with 45 or more years (N=308,707; 86.7%), with 49.0% of these hospitalisations in the 45–64 years age group and 37.7% in the ≥65 years age group (Fig. 1b). Nevertheless, HCC were more frequent in ≥65 age group (57.0% of all HCC related hospitalisations were in that age group) and liver transplant in the 45–64 years age group (65.2% of the liver transplant hospitalisations were in that age group).

In-hospital deaths occurred in 22,431 (6.3%) of the hospitalisations: in 11,558 (4.6%) non-advanced liver disease and in 10,873 (10.4%) advanced liver disease-related hospitalisations.

Periods’ comparison (2012–2015 vs. 2016–2019)Males hospitalisation proportion increased slightly (from 63.5% to 64.7%; P<.001) in 2016–2019 period compared to 2012–2016. There was also an increase in the mean age of hospitalised patients (from 59.4 to 61.7 years; P<.001). Disease severity distribution also changed and proportion of hospitalisations related to N-AdLD increased from 69.4% to 72.4% while AdLD hospitalisations decreased from 30.6% to 27.6% (P<.001) (Table 1).

Changes in distribution of demographics, in-hospital deaths, co-infections, alcohol and other substances abuse and comorbidities between the periods 2012–2015 and 2016–2019.

| Period | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012–2015 | 2016–2019 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Sex | |||

| Men [%] | 63.5% | 64.7% | <0.001 |

| Women [%] | 36.5% | 35.3% | |

| Unknown [%] | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Age-group | |||

| <25 [%] | 0.4 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

| 25–44 [%] | 15.9 | 9.3 | |

| 45–64 [%] | 46.6 | 52.1 | |

| ≥65 [%] | 37.1 | 38.4 | |

| Chronic hepatitis C severity | |||

| N-AdLD [%] | 69.4% | 72.4% | <.001 |

| No signs of hepatic disease [%] | 90.5% | 89.6% | <.001 |

| Compensated cirrhosis [%] | 9.5% | 10.4% | <.001 |

| AdLD [%] | 30.6% | 27.6% | <.001 |

| Decompensated cirrhosis [%] | 56.3% | 53.6% | <.001 |

| HCC [%] | 33.7% | 38.7% | <.001 |

| Liver transplant [%] | 10.0% | 7.7% | <.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | |||

| In-hospital deaths [%] | 6.1% | 6.6% | <.001 |

| Co-infections | |||

| AIDS/HIV [%] | 19.2% | 18.3% | <.001 |

| Hepatitis B [%] | 5.4% | 4.4% | <.001 |

| Tuberculosis [%] | .8% | .6% | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Dementia [%] | 2.0% | 2.8% | <.001 |

| Depression [%] | 4.6% | 5.0% | <.001 |

| Diabetes [%] | 19.6% | 21.5% | <.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia [%] | 9.4% | 13.1% | <.001 |

| Obesity [%] | 3.8% | 5.0% | <.001 |

| Other malignant neoplasms (excluding HCC) [%] | 10.7% | 11.5% | <.001 |

| Pancreatitis [%] | 1.6% | 1.7% | <.001 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia [%] | 1.1% | 1.3% | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease [%] | 4.1% | 5.3% | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease [%] | 3.7% | 4.5% | <.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma [%] | 13.0% | 16.3% | <.001 |

| Heart failure/rheumatic heart disease [%] | 6.5% | 8.6% | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction and ischaemic heart disease [%] | 1.5% | 1.6% | .139 |

| Moderate or severe renal disease [%] | 15.2% | 17.9% | <.001 |

| Rheumatologic diseases [%] | 1.3% | 1.4% | .037 |

| Sicca [%] | .2% | .3% | .005 |

| Alcohol and other substances abuse | |||

| Alcoholism [%] | 16.2% | 19.7% | <.001 |

| Other substance abuse [%] | 19.1% | 18.8% | .011 |

| Opioids abuse | 12.0% | 11.7% | .024 |

| Sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics abuse | .9% | .7% | <.001 |

| Cocaine, cannabis, amphetamines, other psychostimulants, hallucinogens, and psychoactive substance abuses | 4.0% | 6.2% | <.001 |

| Drug combinations and another unknown drug abuse | 7.1% | 5.5% | <.001 |

Source: National Registry of Hospitalisations. Ministry of Health.

AdLD: advanced liver disease; N-AdLD: non-advanced liver disease.

Table 1 also shows the changes in the in-hospital deaths, co-infections, comorbidities, alcohol and other substances abuse between the periods.

In-hospital deaths proportion increased in 2016–2019 period compared to 2012–2015 period from 6.1% to 6.6% (P<.001).

On the contrary, AIDS/HIV, hepatitis B and tuberculosis co-infections decreased (P<.001) in 2016–2019 compared to 2012–2015.

In the case of comorbidities, with the exception of myocardial infarction and ischaemic heart disease, all the rest of comorbidities reported in this study increased in 2016–2019 compared to 2012–2015. Marked increases were noticed for hyperlipidaemia (from 9.4% to 13.1%; P<.001); moderate to severe renal disease (from 15.2% to 17.9%; P<.001) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma (from 13.0% to 16.3%; P<.001).

Overall, alcohol abuse increased from 16.2% in 2012–2015 to 19.7% in 2016–2019 among the chronic HCV hospitalised patients (P<.001). Other substances abuse decreased from 19.1% (2012–2015) to 18.8% (2016–2019). Cocaine, cannabis, amphetamines, other psychostimulants, hallucinogens and psychoactive substances abuse were the only abuse that increased (from 4.0% to 6.2%) in 2016–2019 compared to 2012–2015 period.

Yearly data are shown in Annex 3.

Latest period (2016–2019) clinical characteristics of chronic HCV-related hospitalised patients in SpainTable 2 shows the clinical characteristics of chronic HCV-related hospitalisations between 2016 and 2019.

Clinical characteristics of patients for all chronic, N-AdLD (with no signs of hepatic disease or with compensated cirrhosis), and AdLD (with decompensated cirrhosis, HCC or liver transplant) HCV-related hospitalisations between 2016 and 2019.

| All chronic hepatitis C hospitalised patientsN=156,507 | N-AdLD hospitalised patients | AdLD hospitalised patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All N-AdLDN=113,359 | N-AdLD with no signs of hepatic diseaseN=101,569 | N-AdLD with compensated cirrhosisN=11,790 | All AdLDN=43,148 | AdLD with decompensated cirrhosisN=23,131 | AdLD with HCCN=16,701 | AdLD with liver transplantN=3316 | ||

| In-hospital deaths [%] | 10,274 [6.6%] | 5466 [4.8%] | 4669 [4.6%] | 797 [6.8%] | 4808 [11.1%] | 2383 [10.3%] | 2257 [13.5%] | 168 [5.1%] |

| AIDS/HIV [%] | 28,679 [18.3%] | 24,126 [22.3%] | 21,807 [21.5%] | 2319 [19.7%] | 4553 [10.6%] | 3421 [14.8%] | 962 [5.8%] | 170 [5.1%] |

| Hepatitis B [%] | 6928 [4.4%] | 5573 [4.9%] | 5136 [5.1%] | 437 [3.7%] | 1355 [3.1%] | 872 [3.8%] | 386 [2.3%] | 97 [2.9%] |

| Tuberculosis [%] | 972 [.6%] | 860 [.8%] | 781 [.8%] | 79 [.7%] | 112 [.3%] | 84 [.4%] | 25 [.1%] | 3 [.1%] |

| Dementia [%] | 4399 [2.8%] | 3563 [3.1%] | 3227 [3.2%] | 336 [2.8%] | 836 [1.9%] | 630 [2.7%] | 190 [1.1%] | 16 [.5%] |

| Depression [%] | 7818 [5.0%] | 6218 [5.5%] | 5606 [5.5%] | 612 [5.2%] | 1600 [3.7%] | 982 [4.2%] | 526 [3.1%] | 92 [2.8%] |

| Diabetes [%] | 33,622 [21.5%] | 21,873 [19.3%] | 18,564 [18.3%] | 3309 [28.1%] | 11,749 [27.2%] | 6431 [27.8%] | 4093 [24.5%] | 1225 [36.9%] |

| Hyperlipidaemia [%] | 20,451 [13.1%] | 16,819 [14.8%] | 15,478 [15.2%] | 1341 [11.4%] | 3632 [8.4%] | 1869 [8.1%] | 1446 [8.7%] | 317 [9.6%] |

| Obesity [%] | 7771 [5.0%] | 5905 [5.2%] | 5170 [5.1%] | 735 [6.2%] | 1866 [4.3%] | 1230 [5.3%] | 490 [2.9%] | 146 [4.4%] |

| Malignant neoplasms (excluding HCC) [%] | 19,873 [12.7%] | 15,225 [13.4%] | 13,899 [13.7%] | 1326 [11.2%] | 4648 [10.8%] | 1945 [8.4%] | 2383 [14.3%] | 320 [9.7%] |

| Pancreatitis [%] | 2686 [1.7%] | 1965 [1.7%] | 1665 [1.6%] | 300 [2.5%] | 721 [1.7%] | 508 [2.2%] | 178 [1.1%] | 35 [1.1%] |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia [%] | 2030 [1.3%] | 1731 [1.5%] | 1570 [1.6%] | 161 [1.4%] | 299 [.7%] | 191 [.8%] | 86 [.5%] | 22 [.7%] |

| Cerebrovascular disease [%] | 8252 [5.3%] | 6700 [5.9%] | 6048 [6.0%] | 652 [5.5%] | 1552 [3.6%] | 1012 [4.4%] | 440 [2.6%] | 100 [3.0%] |

| Peripheral vascular disease [%] | 7083 [4.5%] | 5501 [4.9%] | 4942 [4.9%] | 559 [4.7%] | 1582 [3.7%] | 754 [3.3%] | 645 [3.8%] | 183 [5.5%] |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma [%] | 25,559 [16.3%] | 20,713 [18.3%] | 18,670 [18.4%] | 2043 [17.3%] | 4846 [11.2%] | 2979 [12.9%] | 1593 [9.5%] | 274 [8.3%] |

| Heart failure/rheumatic heart disease [%] | 13,466 [8.6%] | 10,548 [9.3%] | 9268 [9.1%] | 1280 [10.9%] | 2918 [6.8%] | 2021 [8.7%] | 745 [4.5%] | 156 [4.6%] |

| Myocardial infarction and ischaemic heart disease [%] | 2429 [1.6%] | 2169 [1.9%] | 2013 [2.0%] | 156 [1.3%] | 260 [.6%] | 148 [.6%] | 76 [.5%] | 36 [1.1%] |

| Moderate or severe renal disease [%] | 28,042 [17.9%] | 18,999 [16.8%] | 16,649 [16.4%] | 2350 [19.9%] | 9043 [21.0%] | 5425 [23.5%] | 2541 [15.2%] | 1077 [32.5%] |

| Rheumatologic disease [%] | 2160 [1.4%] | 1832 [1.6%] | 1682 [1.7%] | 150 [1.3%] | 328 [.8%] | 196 [.8%] | 116 [.7%] | 16 [.5%] |

Source: National Registry of Hospitalisations. Ministry of Health.

AdLD: advanced liver disease; N-AdLD: non-advanced liver disease.

In-hospital deaths occurred in 10,274 (6.6%) chronic HCV-related hospitalisations: 5466 (4.8%) for N-AdLD and 4808 (11.1%) for AdLD-related hospitalisations. Decompensated cirrhosis and HCC were associated to a high in-hospital mortality (10.3% and 13.5%, respectively), while liver transplant group presented lower in-hospital mortality (5.1%).

Regarding co-infections, in 28,679 (18.3%) hospitalisations a HIV-HCV co-infection was reported; in 6928 (4.4%) a HBV-HCV co-infection; and in 972 (.6%) a tuberculosis-HCV co-infection. Co-infections were more frequently observed in hospitalised patients with N-AdLD vs. AdLD for HBV (4.9% vs. 3.1%, P<.001), HIV (22.3% vs. 10.6%, P<.001), and tuberculosis (.8% vs. .3%, P<.001).

Among all chronic HCV-related hospitalisations, in 31,112 (19.9%) there were one co-infection with HBV, HIV or tuberculosis; in 1675 (1.7%) two co-coinfections with HBV, HIV or tuberculosis; and 39 (.02%) patients had all three co-infections (chronic HCV with HBV, HIV and tuberculosis at the same time). HCV+HBV+HIV co-infections were found in 2233 (2.0%) of the hospitalised patients.

Most frequent comorbidity was diabetes (N=33,622; 21.5%). It increased with severity of the disease and was present in more than one third of those with liver transplant (N=1225; 36.9%).

Moderate to severe renal disease was the second most prevalent comorbidity in HCV-related hospitalisations (N=28,042; 17.9%) and was especially associated to decompensated cirrhosis (N=5425; 23.5%) and liver transplant (N=1077; 32.5%) related hospitalisations.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma (N=25,559; 16.3%) and malignant neoplasms (excluding HCC that was considered separately) diagnoses (N=19,873; 12.7%) were frequent as well.

Latest period (2016–2019) alcoholism and other substances abuse in chronic HCV-related hospitalised patients in SpainLatest period proportion of chronic HCV-related hospitalisations reporting alcohol or substances abuse among the diagnoses was high (Table 3). Any abuse was reported in 48,506 (31.0%) hospitalisations, alcohol abuse in 30,782 (19.7%), and other substances abuse in 29,388 (18.8%). Overall, 11,664 (7.5%) hospitalised patients were coded as suffering both, alcohol and other substances abuse. In general, alcohol and substances abuse decreased with severity of the disease.

Alcohol and other substances abuse characteristics of patients for all chronic, N-AdLD (with no signs of hepatic disease or with compensated cirrhosis), and AdLD (with decompensated cirrhosis, HCC or liver transplant) HCV-related hospitalisations between 2016 and 2019.

| All chronic hepatitis C hospitalised patientsN=156,507 | N-AdLD hospitalised patients | AdLD hospitalised patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All N-AdLDN=113,359 | N-AdLD with no signs of hepatic diseaseN=101,569 | N-AdLD with compensated cirrhosisN=11,790 | All AdLDN=43,148 | AdLD with decompensated cirrhosisN=23,131 | AdLD with HCCN=16,701 | AdLD with liver transplantN=3316 | ||

| Alcoholism [%] | 30,782 [19.7%] | 19,630 [17.3%] | 16,506 [16.3%] | 3124 [26.5%] | 11,152 [25.8%] | 6713 [29.0%] | 3778 [22.6%] | 661 [19.9%] |

| Other substance abuse [%] | 29,388 [18.8%] | 23,741 [20.9%] | 21,479 [21.1%] | 2262 [19.2%] | 5647 [13.1%] | 3913 [16.9%] | 1452 [8.7%] | 282 [8.5%] |

| Opioids abuse | 18,331 [11.7%] | 15,033 [13.3%] | 13,562 [13.4%] | 1471 [12.5%] | 3298 [7.6%] | 2456 [10.6%] | 696 [4.2%] | 146 [4.4%] |

| Sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics abuse | 1153 [.7%] | 1025 [.9%] | 942 [.9%] | 83 [.7%] | 128 [.3%] | 91 [.4%] | 37 [.2%] | 0 [.0%] |

| Cocaine, cannabis, amphetamines, other psychostimulants, hallucinogens, and psychoactive substance abuses | 9645 [6.2%] | 7920 [7.0%] | 7256 [7.1%] | 664 [5.6%] | 1725 [4.0%] | 1175 [5.1%] | 482 [2.9%] | 68 [2.1%] |

| Drug combinations and another unknown drug abuse | 8578 [5.5%] | 6769 [6.0%] | 6095 [6.0%] | 674 [5.7%] | 1809 [4.2%] | 1158 [5.0%] | 541 [3.2%] | 110 [3.3%] |

Source: National Registry of Hospitalisations, Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare.

AdLD: advanced liver disease; N-AdLD: non-advanced liver disease.

In the case of alcohol, abuse was clearly associated to cirrhosis. Alcohol abuse was observed in 26.5% of the hospitalisations with compensated and in 29.0% in those with decompensated cirrhosis.

Prevalence of other substances abuse decreased with severity from 21.1%, in those with no signs of hepatic disease, to 8.7% and 8.5%, in those with HCC and liver transplant, respectively.

Sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics abuse was low (N=1153; .7%), while psychostimulants, hallucinogens and psychoactive substances abuses were coded in 9645 (6.2%) hospitalisations, opioids abuse in 18,331 (11.7%), and other combinations in 8578 (5.5%).

DiscussionThe Spanish Strategic Plan for Tackling Hepatitis C have affected positively since its implementation in 2015 by reducing the HCV-related hospitalisation rates. So much so that in 2018, compared to 2014, the HCV hospitalisation rates decreased 26%.4,5 As a consequence of the Strategic Plan prioritisation of severe cases to be treated, additionally, the proportion of AdLD hospitalisations among all hospitalisations decreased from 33.0% in 2014–2015 to 27.9% in the latest period (2016–2019).5

Although those positive results in the hospitalisation rates, majority of infections in Spain were before 19901 which means that most of the HCV patients have been chronically infected during decades. In that line, further research was necessary to characterise current clinical characteristics of HCV-related hospitalised patients and their hepatic and extrahepatic manifestations. Thus, the information provided in this study could help to understand the complexity and HCV health-related patients’ needs that can trigger patients’ health after hepatitis C eradication.

For this purpose, changes in comorbidities of chronic HCV-related hospitalisations in Spain were evaluated comparing 2012–2015 and 2016–2019 periods. Slight increases in prevalence of comorbidities were observed between periods in most comorbidities as ageing and disease progression continue affecting non-treated patients.

Between 2016 and 2019, around 20% of chronic HCV-related hospitalisations in Spain had an HBV (4.4%), HIV (18.3%) or tuberculosis (.6%) co-infection associated. Risk of mortality associated with concurrent co-infections for HCV, HBV and HIV have been assessed previously by Butt et al.,13 being HCV+HBV+HIV and HCV+HIV the ones associated with higher risk of death. Hence, the relevance of providing anti-HCV treatment to tuberculosis and HIV patients.

Younossi et al.7 reported diabetes and depression as the main extra-hepatic manifestations of the disease, finding diabetes in 15% of patients, chronic renal disease in 16.2% and depression in 25% of patients. Our results for 2016–2019 period show that diabetes (21.5%) and moderate or severe renal disease (17.9%) are the main frequent extrahepatic manifestations reported in the National Hospitalisation Registry for HCV-related hospitalisations. Both prevalence's very similar to the prevalence's found in other studies developed in hospitalised HCV patients.24

Depression, nevertheless, was reported in 5% of hospitalised patients in our study, which is far from the pooled 25% obtained in Younossi et al. work.7 Other Spanish studies have evaluated depression in chronic hepatitis C patients finding higher prevalence (18.2%)25 or cumulative incidence (43.3%)26 of any depressive disorder in treated patients. Therefore, depression may be underreported in chronic HCV hospitalised patients.

Prior meta-analyses have associated HCV with an increased risk of extrahepatic malignancies,20 as pancreatic,27,28 kidney,29,30 lung,31 B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL),32,33 and thyroid34 cancer. Prevalence of malignancies (excluding HCC) among HCV-related hospitalisations in our study was high, around 13%, although similar to other studies carried out in the hospital setting.24

A high prevalence of alcohol or other substances abuse among HCV hospitalisation was also found between 2016 and 2019. Alcohol abuse was especially high in HCV-related hospitalisations with compensated or decompensated cirrhosis, which is common as it is a factor for cirrhosis progression. However, alcohol abuse was still high in hospitalisations in patients with HCC. Regarding other substances abuse, we observed higher abuse in those with lower progression of the disease, which is also associated with a lower number of years of disease progression and younger age groups.

Some of the limitations of the data used for this study are described in our prior analyses, as the change of ICD-9 to ICD-10 that entered into force in 2016 in Spain for the National Registry of Hospitalisation.4,5 However, consistency on the data with the ICD version was observed and reported in our previous analyses4,5 and this one.

Some specific limitations of this study are its descriptive nature and the National Registry of Hospitalisations own limitations. It is estimated that the National Hospitalisation Registry cover around 98% of public hospital admissions, and 99.5% of the population in Spain.35 Additional limitations of the National Hospitalisation Registry have been described in previous studies, but some of them do not affect this study. Among them, one known limitation found in a previous study developed by our group is that it does not collect well mild symptoms as fever, cough, constipation, diarrhoea, etc. not studied in the present research.36 However, we have explained that we consider the prevalence of depression found in HCV-related hospitalisations was too low compared to other studies and might be underestimated. Another limitation is that it does not provide information on each diagnosis date and only ongoing diagnoses during the hospitalisation are recorded, past clinical history is not shown in the registry, so we may be underestimating some HCV associated syndromes.

As a strength, the consistency found in this study between periods for patients’ clinical characteristics brings some light to one pending question: “if those patients that achieve sustained virological response are being coded by mistake as HCV-related hospitalisations at the National Registry of Hospitalisation”. Our results, nevertheless, seem to suggest that they are correctly introduced in the system by not receiving HCV-related codes. However, as there is no ICD codes created for those who achieve hepatitis C eradication, cured patients are lost in the registry with no possibility of tracking them.

Despite the limitations, this registry has proved to be useful for planning health resources and evaluating the impact at national level of those diseases needing for hospitalisation. Results continue emphasising the need of continuing treating all HCV infected persons to avoid the observed disease progression and its impact in patients’ health.

ConclusionsIn spite of the reduction in AdLD hepatitis C-related hospitalisations due to treatment implementation targeted primarily to the more severe cases, high and increasing prevalence of comorbidities and risks factors for worse prognosis have been found among HCV chronic hospitalisations in this study. Chronic HCV patients’ progression during decades and risk factors for worse progression found could compromise regression of hepatic and extrahepatic manifestations of the disease after sustained virological response.

Ethics approvalNo ethics approval is required for the use and analysis of the Spanish National Hospitalisation Registry as it provides anonymised patient data.

Author's contributionAll authors contributed to the study. M.G-E designed the study, M.G-E and R.H set the objectives and elaborated the study plan. M-G-E and J.F-H performed the analysis. M.G-E and R.H were actively involved in the ICD-9 to ICD-10 version mapping of the clinical codes for the comorbidity's subgroups definition. M.G-E and J.F-H wrote the first draft. J.F-H and R.H provided input to the first draft and reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

FundingNo funding was received.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statementThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| Advanced Liver Disease (AdLD) ICD codes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AdLD category | Pathology description | ICD-9 CM | ICD-10 |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | Chronic hepatitis C with hepatic coma | Diagnoses: 070.44; 070.54+572.2 | Diagnoses: B18.2+K72.11; B18.2+K72.91 |

| Unspecified viral hepatitis C with hepatic coma | Diagnoses: 070.71; 070.70+572.2; 070.7+572.2 | Diagnoses: B19.21; B19.20+K72.11; B19.20+K72.91;B19.2+K72.11; B19.2+K72.91 | |

| Hepatitis C carrier with hepatic coma | Diagnoses: V02.62+572.2 | Diagnoses: Z22.52+K72.11; Z22.52+K72.91 | |

| Encephalopathy not otherwise specified | Diagnoses: 348.3x | Diagnoses: G93.4x | |

| Esophageal varices in diseases classified elsewhere with or without bleeding | Diagnoses: 456.0; 456.1; 456.2xProcedures: 42.91; 96.06 | Diagnoses: I85.01; I85.00; I85.1; I85.11; I85.10Procedures: 06L3xxx; 0DL57DZ; 0DL58DZ | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | Diagnoses: 572.2; 348.30 | Diagnoses: K72.9x; G93.40 | |

| Portal hypertension | Diagnosis: 572.3 | Diagnosis: K76.6 | |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | Diagnosis: 572.4 | Diagnosis: K76.7 | |

| Other sequels of chronic hepatic disease | Diagnosis: 572.8 | Diagnosis: K72.10 | |

| Jaundice | Diagnosis: 782.4 | Diagnosis: R17 | |

| Other ascites | Diagnoses: 789.5; 789.59Procedure: 54.91 | Diagnosis: R18.8Procedures: 0F9xxxx | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Malignant neoplasm of liver and intrahepatic bile duct | Diagnoses: 155.x | Diagnoses: C22.x |

| Malignant neoplasm associated with transplant organ+Liver transplant | Diagnoses: 199.2+996.82 | Diagnoses: C80.2+T86.4x | |

| Liver transplant | Liver transplant | Diagnosis: V42.7;Procedures: 50.5x | Diagnosis: Z94.4;Procedures: 0FY00Z0; 0FY00Z1; 0FY00Z2 |

| Complications of transplanted liver | Diagnosis: 996.82 | Diagnosis: T86.4x | |

Source: National Registry of Hospitalisations, Ministry of Health, Consumption, and Social Welfare.

AdLD: advanced liver disease; N-AdLD: non-advanced liver disease.

| Diagnosis/procedure | ICD-9 CM | ICD-10 |

|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities codes | ||

| HIV/AIDS | 042; 079.53; V08 | B20; B97.35; Z21 |

| Hepatitis B | 070.2x; 070.3x; V02.61 | B16.x; B18.0; B18.1; B19.1; B19.10; B19.11; Z22.51 |

| Tuberculosis | 010.xx-018.xx | A15.xx-A19.xx |

| Alcoholism | 291.xx; 303.xx; 305.0x | F10.xx |

| Other substance abuse | 304.xx | F11.20; F11.21; F13.20; F13.21; F14.20; F14.21; F12.20; F12.21; F16.20; F16.21; F15.20; F15.21; F19.20; F19.21 |

| - Opioids abuse | 304.0x | F11.20; F11.21 |

| - Sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics abuse | 304.1x | F13.20; F13.21 |

| - Cocaine, cannabis, amphetamines, other psychostimulants, hallucinogens, and psychoactive substance abuses | 304.2x; 304.3x; 304.4x; 304.5x | F14.20; F14.21; F12.20; F12.21; F16.20; F16.21; F15.20; F15.21 |

| - Drug combinations and another unknown drug abuse | 304.6x; 304.7x; 304.8x; 304.9x | F19.20; F19.21 |

| Dementia | 290.xx; 331.0; 294.1x; 294.2x | F01.xx-F03.xx; G30.x |

| Depression | 296.2x; 296.3x; 309.0; 309.1; 311 | F32.xx; F33.xx; F43.21 |

| Diabetes | 249.xx; 250.xx | E08.xx-E13.xx |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 272.x | E77.x; E78.xx (except E78.71 and E78.72); E88.1; E88.2; E88.89; E75.21; E75.22; E75.240; E75.241; E75.242; E75.243; E75.248; E75.249 |

| Obesity | 278.0x | E66.xx |

| Acute or chronic pancreatitis | 577.0; 577.1 | K85.xx; K86.0; K86.1 |

| Malignant neoplasms (excluding HCC) | 140.x-208.x (except 155.x) | C00.x-C96.x; D00.x-D09.x (except C22.x) |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 342.xx; 344.xx | G81.xx; G82.xx; G83.xx |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 430.x-438.x | I60.xx-I63.xx; I65.xx-I69.xx (except I67.0; I67.3; and I67.83); and G45.xx (except G45.3) |

| Moderate or severe renal disease | 403.xx; 404.xx; 580.xx-586.xx | I12.xx; I13.xx; N00.xx-N08.xx; N14.xx; N15.0; N15.8; N15.9; N16.xx-N19.xx |

| Heart failure/rheumatic heart disease | 398.xx; 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 428.xx | I09.0; I09.81; I09.89; I09.9; I11.0; I50.xx |

| Myocardial infarction and ischaemic heart disease | 410.xx; 411.xx | I21.xx; I20.0; I24.x |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 440.x-447.x | I70-I75; I77; I79; M30; M31 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma | 491.xx-493.xx; 496 | J41.xx-J45.xx |

| Rheumatologic disease | 710.xx; 714.xx; 720.0; 725 | M32.xx-M34.xx; M35.0x; M35.1x; M35.3; M35.5x; M35.8x; M35.9; M36.0x; M36.8x; M06.xx; M07.xx; M08.xx; M12.0x; |

| Year | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| In-hospital deaths [%] | 3108 | 6.2 | 3031 | 6.0 | 2963 | 5.9 | 3055 | 6.3 | 2770 | 6.6 | 2607 | 6.4 | 2507 | 6.6 | 2390 | 6.6 |

| AIDS/HIV [%] | 9775 | 19.5 | 9961 | 19.7 | 9775 | 19.5 | 8756 | 18.0 | 7662 | 18.4 | 7471 | 18.5 | 7086 | 18.5 | 6460 | 17.9 |

| Hepatitis B [%] | 2758 | 5.5 | 2832 | 5.6 | 2687 | 5.3 | 2439 | 5.0 | 1989 | 4.8 | 1808 | 4.5 | 1619 | 4.2 | 1512 | 4.2 |

| Tuberculosis [%] | 484 | 1.0 | 402 | 0.8 | 376 | 0.7 | 331 | 0.7 | 274 | 0.7 | 234 | 0.6 | 237 | 0.6 | 227 | 0.6 |

| Dementia [%] | 932 | 1.9 | 924 | 1.8 | 1005 | 2.0 | 1055 | 2.2 | 1121 | 2.7 | 1132 | 2.8 | 952 | 2.5 | 1194 | 3.3 |

| Depression [%] | 2277 | 4.5 | 2310 | 4.6 | 2389 | 4.8 | 2246 | 4.6 | 1941 | 4.7 | 2041 | 5.0 | 1949 | 5.1 | 1887 | 5.2 |

| Diabetes [%] | 9652 | 19.2 | 9931 | 19.6 | 10051 | 20.0 | 9567 | 19.7 | 8883 | 21.3 | 8615 | 21.3 | 8256 | 21.6 | 7868 | 21.8 |

| Hyperlipidaemia [%] | 4157 | 8.3 | 4607 | 9.1 | 4922 | 9.8 | 5017 | 10.3 | 4867 | 11.7 | 4869 | 12.0 | 5341 | 14.0 | 5374 | 14.9 |

| Obesity [%] | 1727 | 3.4 | 1849 | 3.7 | 1921 | 3.8 | 2053 | 4.2 | 1796 | 4.3 | 1943 | 4.8 | 1967 | 5.1 | 2065 | 5.7 |

| Other malignant neoplasms (excluding HCC) [%] | 5151 | 10.3 | 5314 | 10.5 | 5473 | 10.9 | 5524 | 11.4 | 4945 | 11.9 | 5039 | 12.4 | 4961 | 13.0 | 4928 | 13.6 |

| Pancreatitis [%] | 790 | 1.6 | 778 | 1.5 | 808 | 1.6 | 729 | 1.5 | 699 | 1.7 | 638 | 1.6 | 674 | 1.8 | 675 | 1.9 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia [%] | 545 | 1.1 | 538 | 1.1 | 619 | 1.2 | 591 | 1.2 | 493 | 1.2 | 525 | 1.3 | 529 | 1.4 | 483 | 1.3 |

| Cerebrovascular disease [%] | 1992 | 4.0 | 2003 | 4.0 | 2161 | 4.3 | 2099 | 4.3 | 2034 | 4.9 | 2178 | 5.4 | 2014 | 5.3 | 2026 | 5.6 |

| Peripheral vascular disease [%] | 1641 | 3.3 | 1911 | 3.8 | 1958 | 3.9 | 1877 | 3.9 | 1726 | 4.1 | 1813 | 4.5 | 1756 | 4.6 | 1788 | 4.9 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma [%] | 6156 | 12.3 | 6447 | 12.7 | 6541 | 13.0 | 6769 | 13.9 | 6251 | 15.0 | 6416 | 15.8 | 6454 | 16.9 | 6438 | 17.8 |

| Heart failure/rheumatic heart disease [%] | 3291 | 6.6 | 3280 | 6.5 | 3197 | 6.4 | 3276 | 6.7 | 3345 | 8.0 | 3356 | 8.3 | 3401 | 8.9 | 3364 | 9.3 |

| Myocardial infarction and ischaemic heart disease [%] | 736 | 1.5 | 762 | 1.5 | 790 | 1.6 | 689 | 1.4 | 610 | 1.5 | 628 | 1.6 | 616 | 1.6 | 575 | 1.6 |

| Moderate or severe renal disease [%] | 7416 | 14.8 | 7499 | 14.8 | 7878 | 15.7 | 7568 | 15.6 | 7278 | 17.5 | 7073 | 17.5 | 6871 | 18.0 | 6820 | 18.9 |

| Rheumatologic diseases [%] | 574 | 1.1 | 667 | 1.3 | 687 | 1.4 | 666 | 1.4 | 572 | 1.4 | 543 | 1.3 | 508 | 1.3 | 537 | 1.5 |

| Alcoholism [%] | 7836 | 15.6 | 7924 | 15.6 | 8162 | 16.2 | 8351 | 17.2 | 7377 | 17.7 | 8078 | 20.0 | 7671 | 20.1 | 7656 | 21.2 |

| Other substance abuse [%] | 9653 | 19.2 | 9675 | 19.1 | 9609 | 19.1 | 9226 | 19.0 | 7443 | 17.8 | 7504 | 18.5 | 7271 | 19.0 | 7170 | 19.8 |

| Total Hepatitis C hospitalisations | 50,207 | 100 | 50,656 | 100 | 50,230 | 100 | 48,579 | 100 | 41,698 | 100 | 40,482 | 100 | 38,201 | 100 | 36,126 | 100 |