Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease (CD), are at risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer, above all if they have taken or are currently taking thiopurine agents.1 The association between IBD and melanoma was recently explored in an extensive meta-analysis of 12 studies with a total of 170000 patients.2 The authors concluded that, irrespective of the use of both thiopurine agents and anti-TNF, IBD increased the risk of melanoma, with a relative risk of 1.37 (95% CI 1.10–1.70).

Despite the considerable advances made in the treatment of melanoma following the introduction of antitarget drugs, such as vemurafenib, and immunomodulatory antibodies, such as ipilimumab and nivolumab, adjuvant treatment for high risk melanoma has not changed since the end of the 1990s. High-dose interferon (IFN) alfa 2b (IFN α-2b), following the regimen used by Kirkwood et al.,3 is the only therapy shown to prolong progression-free survival, although its benefit in terms of overall survival is less clear. The immunomodulatory effect of IFN on IBD is not fully understood.

We present the case of a woman of 42 years of age at the time of writing, a smoker of up to 0.5 pack-years, who had been diagnosed with perianal and ileocolic CD (A2L3pB1) at 27 years of age. She was initially treated with azathioprine and long-term corticosteroids, but made poor progress in terms of both gastrointestinal and general symptoms (artralgia, asthenia, etc.). She was also given infliximab, which was withdrawn due to anaphylactic reaction, and adalimumab, which was withdrawn after 1 year due to a gradual loss of efficacy. Despite the therapy received, the perianal disease worsened over time and the patient developed various pyogenic complications (fistulas and abscesses), undergoing up to 7 surgical procedures over the course of 4 years to drain the abscesses and to place setons in the fistula.

Ten years after the diagnosis of CD, the patient presented with a suspicious pigmented lesion on her left shoulder. Excisional biopsy revealed malignant nodular melanoma with microscopic ulceration and more than 6mitoses/mm2. Breslow thickness was 3.4mm (Clark stage III). An extension whole-body CT scan was performed, together with selective biopsy of 3 sentinel lymph nodes, which were negative on analysis. The patient was finally diagnosed with stage IIb melanoma (pT3bN0M0). Surgical treatment was completed with extended resection to include margins shown to be disease-free on histopathology. The patient was referred to the Medical Oncology Department where, in view of the ulceration and number of mitoses/mm2 of the primary tumour, and despite the absence of nodal involvement, she was started on adjuvant treatment with high-dose IFN α-2b, following the regimen proposed by Kirkwood et al. (15 million IU, 3 times/week for 48 weeks).3 Before starting IFN treatment, the patient's quality of life was poor (up to 4 or 5 bowel movements per day, with severe asthenia, in addition to the perianal symptoms described above), and she was receiving 150mg/day azathioprine, which was maintained during IFN therapy.

During IFN treatment, the patient presented mild toxicity (grade 1–2), which included influenza-like illness, asthenia, myalgia, headache, dysgeusia, nausea, enuresis and mild sensory neuropathy. These symptoms, however, did not require dose reduction, and the treatment was completed.

A few weeks after completion of IFN therapy, the patient reported improvement in her CD, and since then has only required 1 seton-placement procedure to manage her perianal disease. Her overall health is very good, with no gastrointestinal symptoms, and all immunosuppressants and immunomodulators given for CD have been discontinued. After 5 years of follow-up, she remains cancer-free.

Interferons are a group of antiviral molecules that were first introduced in clinical practice in 1957. Based on their receptor types on the cell membrane, IFNs are classified into type i and type ii. IFN α coding genes are located on human chromosome 9, and the protein has many different biological functions, including antiproliferative and immunomodulatory activities and potent antiviral activity.4 IFN α acts by regulating the expression of a wide range of genes involved in intracellular signalling pathways. After binding to its specific membrane receptor, IFN α is thought to intervene in the regulation of over 300 genes and molecular pathways, including inducible nitric oxide synthase and major histocompatibility complex I and II.

Due to these pleiotropic effects, IFNs have been used in the treatment of many different diseases: multiple sclerosis (IFN β), various types of cancer, such as malignant melanoma, and chronic hepatitis B and C virus infections. Less information is available on the effects of IFN on other chronic autoimmune diseases, such as CD. As mentioned above, it is not uncommon for IBD patients to receive IFN, given the prevalence of melanoma2 in this patient population. The following is a summary of the scant evidence available regarding the benefit of IFN in CD.

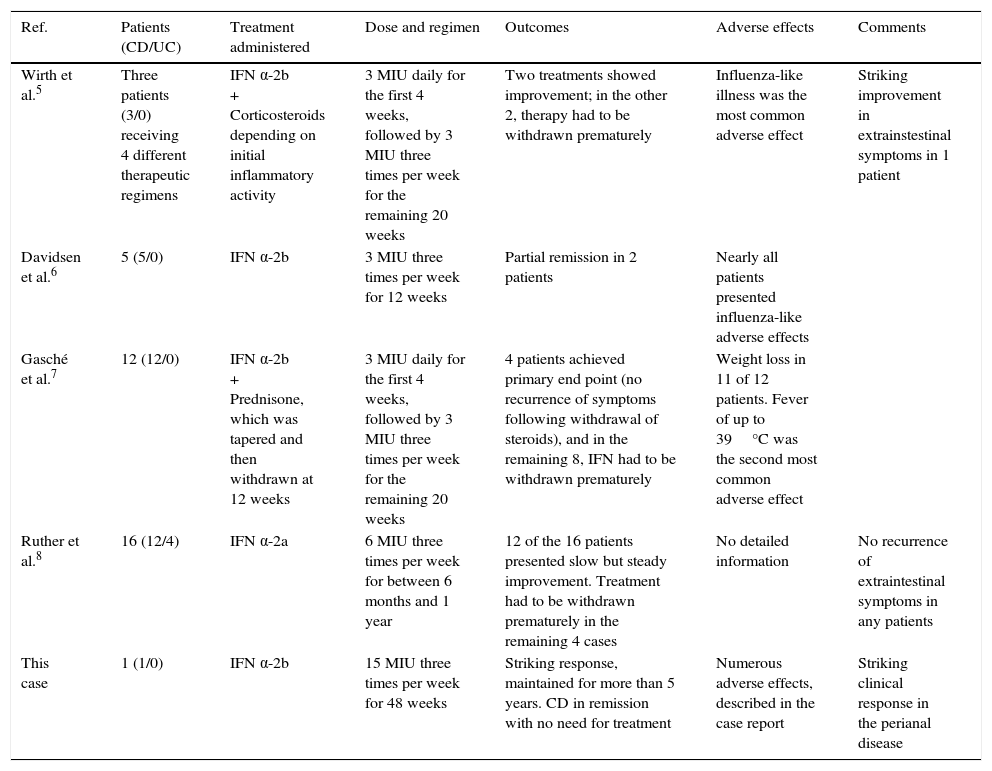

Wirth et al.5 were the first to address the effect of IFN α-2b on CD. In this small study, the authors gave 4 courses of therapy to 3 CD patients for 24 weeks. Corticosteroid dosage depended on the initial inflammatory activity determined by the Crohn Disease Activity Index (CDAI index). Two courses of treatment had to be stopped at 12 and 14 weeks in all patients, due to increased disease activity. During the other 2 therapies, disease activity decreased by 118 and 70 CDAI points. In particular, the progress made by 1 female patient with abundant extraintestinal inflammatory activity was remarkable.

In another pilot study,6 5 patients with active CD (CDAI between 235 and 517 points) were treated with IFN α-2b. All patients presented adverse effects, predominantly influenza-like symptoms that were controlled with paracetamol; partial disease remission was achieved in only 2 cases (decline in CDAI scores of 39% and 50%).

Gasché et al.,7 meanwhile, published a larger series of 12 patients with active CD treated with IFN α-2b for 24 weeks. All patients received prednisone, which was tapered until it could be withdrawn completely after 12 weeks. The primary end point (to observe whether corticosteroids could be discontinued without worsening of clinical symptoms) was achieved in 4 patients. IFN was withdrawn prematurely in the remaining cases due to lack of response and the onset of serious adverse effects (particularly fever and weight loss).

Another interesting study in IFN was published by a group of German researchers,8 who were the first to associate exacerbations of IBD with herpesvirus upper respiratory tract infections. They hypothesised that IFN α-2a, which boosts the natural antiviral response to herpesvirus, would be an effective treatment in these cases. The study included 12 patients with CD and 4 with UC. After discontinuing background therapy, patients were treated with IFN α-2a for between 6 months and 1 year. Twelve of the 16 study patients showed gradual improvement after an average of 8 weeks. The most striking improvement was remission of the extraintestinal manifestations, which did not recur over the study period. The remaining 4 patients showed no improvement, and treatment had to be discontinued prematurely.

Contrasting results, however, have been reported in case series and isolated studies in which IFN therapy has been associated with the development or exacerbation of IBD symptoms. In particular, a Portuguese group9 reported 3 cases of IBD (1 UC and 2 CD) with onset shortly (between 3 and 12 months) after finalising treatment with peg-IFN and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. However, a recent retrospective study in 15 patients (8 with UC and 7 with CD) published by the Mayo Clinic10 reported only 1 case of IBD exacerbation during or after treatment with IFN for viral hepatitis. Based on their findings, the authors concluded that IFN is as safe and effective in IBD patients as in healthy controls. The role of IFN in both remission and exacerbation in IBD could be explained by the fact that it is a pro-inflammatory cytokine which stimulates a Th1-type immune response (which predominates in CD), but also has anti-inflammatory properties that diminish the Th2-type response (which is up-regulated in UC).10 This hypothesis has not been corroborated in the literature.

Table 1 summarises the findings of the foregoing studies, and suggests that IFN therapy has a variable effect on CD. In some patients it achieves partial remission, in others it achieves striking improvement (particularly in extraintestinal manifestations), while in others it has little or no effect, or even increases disease activity, leading to early suspension of therapy. Most of the studies presented precede the introduction of biologic agents, and are also subject to significant methodological limitations, such as small sample size, no blinding (although this is hardly practical in IFN treatment, given its unmistakable adverse effects) and no control group. The case presented here is particularly interesting for 2 reasons: the dose of IFN was much higher than that reported in other studies, and the spectacular clinical response.

Studies on the use of interferon-α in Crohn disease.

| Ref. | Patients (CD/UC) | Treatment administered | Dose and regimen | Outcomes | Adverse effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wirth et al.5 | Three patients (3/0) receiving 4 different therapeutic regimens | IFN α-2b + Corticosteroids depending on initial inflammatory activity | 3 MIU daily for the first 4 weeks, followed by 3 MIU three times per week for the remaining 20 weeks | Two treatments showed improvement; in the other 2, therapy had to be withdrawn prematurely | Influenza-like illness was the most common adverse effect | Striking improvement in extrainstestinal symptoms in 1 patient |

| Davidsen et al.6 | 5 (5/0) | IFN α-2b | 3 MIU three times per week for 12 weeks | Partial remission in 2 patients | Nearly all patients presented influenza-like adverse effects | |

| Gasché et al.7 | 12 (12/0) | IFN α-2b + Prednisone, which was tapered and then withdrawn at 12 weeks | 3 MIU daily for the first 4 weeks, followed by 3 MIU three times per week for the remaining 20 weeks | 4 patients achieved primary end point (no recurrence of symptoms following withdrawal of steroids), and in the remaining 8, IFN had to be withdrawn prematurely | Weight loss in 11 of 12 patients. Fever of up to 39°C was the second most common adverse effect | |

| Ruther et al.8 | 16 (12/4) | IFN α-2a | 6 MIU three times per week for between 6 months and 1 year | 12 of the 16 patients presented slow but steady improvement. Treatment had to be withdrawn prematurely in the remaining 4 cases | No detailed information | No recurrence of extraintestinal symptoms in any patients |

| This case | 1 (1/0) | IFN α-2b | 15 MIU three times per week for 48 weeks | Striking response, maintained for more than 5 years. CD in remission with no need for treatment | Numerous adverse effects, described in the case report | Striking clinical response in the perianal disease |

CD: Crohn disease; IFN: interferon; MIU: million international units; UC: ulcerative colitis.

In view of the scant scientific evidence available, therapy should be tailored to the needs of each patient with CD requiring treatment with IFN, and the course of the IBD and the specific disease treated should be closely monitored.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ferre Aracil C, Rodríguez de Santiago E, García García de Paredes A, Aguilera Castro L, Soria Rivas A, López SanRomán A. Remisión completa de enfermedad de Crohn tras tratamiento con megadosis de interferón alfa por un melanoma maligno. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:397–400.