Despite the development and incorporation of new therapeutic strategies, such as biologic therapy and small molecules, corticosteroids still play an important role in inducting Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) remission. Variables like indicating the right doses at the right time, in adequate intervals, the security of these drugs and the pharmacological alternatives available must be considered by the providers when they are indicated to patients with IBD. Although the use of corticosteroids is considered as a marker of quality of care in patients with IBD, the use of these drugs in the clinical practice of IBD is far from being the correct one. This review article is not intended to be just a classic review of the indications for corticosteroids. Here we explain the scenarios in which, in our opinion, steroids would not be an appropriate option for our patients, as well as the most frequent mistakes we make in our daily practice when using them.

A pesar del desarrollo e incorporación de nuevas estrategias terapéuticas, como son la terapia biológica y las moléculas pequeñas, los corticoides aún cumplen un papel importante en la inducción de la remisión de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII). Variables como la indicación en el momento apropiado, la dosis correcta, duración en intervalos adecuados, la seguridad de estos fármacos y las alternativas farmacológicas disponibles deben ser siempre consideradas por el equipo tratante al momento de su indicación en pacientes con EII. Aunque el uso de corticoides es considerado un marcador de calidad de atención en pacientes con EII, en la actualidad, el uso de estos fármacos en la práctica clínica de la EII dista mucho de ser el más correcto. Este artículo de revisión no pretende ser solamente una revisión clásica de las indicaciones de los corticoides, sino que explicamos aquí los escenarios en los que en nuestra opinión no serían una opción adecuada para nuestros pacientes, así como los errores más frecuentes que cometemos en nuestra práctica clínica diaria al utilizarlos.

Almost immediately after their introduction into therapy as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis over 70 years ago, corticosteroids became essential drugs in the treatment of immune-mediated diseases. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) was no exception, and after numerous clinical observations and the first randomised controlled trial conducted in Gastroenterology by Sidney Truelove, Lloyd Witts and a group of English pioneers, corticosteroids became the treatment of choice for moderate to severe flare-ups of first ulcerative colitis (UC) and then Crohn's disease (CD). After six weeks, 41.3% of UC patients treated with cortisone 25 mg four times daily were in clinical remission, compared to 15.8% in the placebo-treated group (p <0.001). Sigmoidoscopy assessment also showed a significant difference in achieving endoscopic remission or response (p <0.02).1 The National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study (NCCDS) showed that, in 250 patients with active CD, the use of prednisone 0.5 to 0.75 mg/kg/day with tapering off as per protocol for 17 weeks led to clinical remission in 60% of patients compared to 30% in the placebo-treated group.2 However, almost 70 years after the publication of these trials, the use of corticosteroids in IBD clinical practice is still far from optimal. A study involving 2,385 patients reported that 14.8% met the definition for corticosteroid excess or dependence, with avoidable corticosteroid use in 50.7% of cases (annual incidence: 6.2%).3 A recent retrospective Spanish study, which included 392 patients with IBD in remission on immunosuppressive therapy, showed that 23% received at least one course of corticosteroids during the follow-up period.4 However, this strategy was only effective in the long term in one third of patients. Variables such as prescribing at the most appropriate time, correct dosage, duration at suitable intervals and safety of these drugs should always be considered by the treating team when prescribing to patients with IBD.5 There is no doubt that ongoing education of patients, general practitioners and sub-specialists by IBD programme members is essential to reduce the excessive and prolonged use of corticosteroids.6 We believe that reviewing the basic concepts with the currently available evidence can help us avoid mistakes, which are still all too common.

For this review, we conducted an electronic literature search using the MEDLINE (PubMed) database, Google Scholar and ResearchGate. We only included articles published in English and Spanish. The keywords used in the search were: inflammatory bowel disease; Crohn's disease; ulcerative colitis; corticosteroids; steroids; therapy; and safety. We included both retrospective and prospective studies with a cross-sectional design and systematic reviews.

Corticosteroids: general concepts and formulationsCorticosteroids are anti-inflammatory agents indicated for the treatment of patients with UC and CD with moderate to severe inflammatory bowel activity or a mild flare-up refractory to mesalazine at suitable doses.7–9 These drugs are highly lipophilic compounds, so they are widely bioavailable and are transported into the blood by corticosteroid-binding globulin and, to a lesser extent, albumin. Corticosteroids have the ability to diffuse across cell membranes and interact with the glucocorticoid receptor. Several mechanisms have been suggested for their mode of action, including inhibition of proinflammatory proteins such as nuclear factor ĸß and ligand-independent transactivation domain AP-1; decreased expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α, IL-1ß and IL-8, and of mediators such as transforming growth factor-ß3 and IL-10; inhibition of proliferation of T and B lymphocytes; and promotion of a tolerant macrophage profile.10

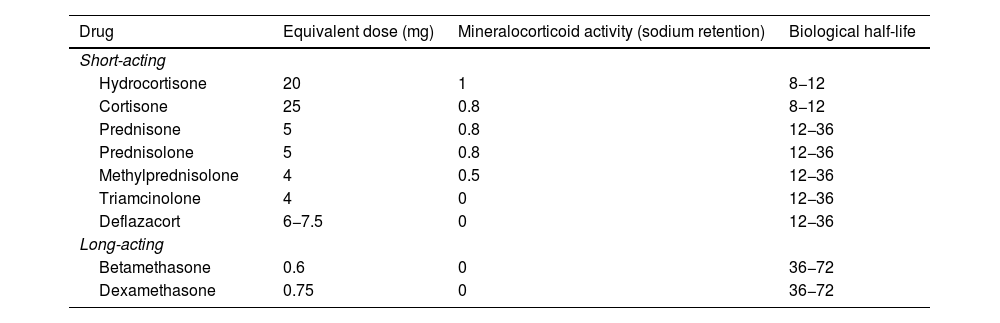

Corticosteroid formulations in IBD include intravenous drugs (hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone and dexamethasone), oral drugs with systemic effect (prednisone, prednisolone and deflazacort) and topical drugs (budesonide, budesonide multimatrix [MMX] and beclomethasone dipropionate), as well as rectally administered medications with systemic effect (hydrocortisone, prednisolone, triamcinolone, methylprednisolone and betamethasone) and with topical action (budesonide, beclomethasone and prednisolone-metasulfobenzoate).9 The dosage equivalents of systemic corticosteroids are shown in Table 1. Before prescribing any of these drugs in a flare-up of CD or UC, we have to consider not only the severity of the inflammatory activity but also the extent of the affected area, the patient's history and the available pharmacological alternatives.7–9 It is this deliberation that will enable us to define the best therapeutic strategy to improve the quality of life of IBD patients.

Equivalent doses of systemic corticosteroids used in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

| Drug | Equivalent dose (mg) | Mineralocorticoid activity (sodium retention) | Biological half-life |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-acting | |||

| Hydrocortisone | 20 | 1 | 8−12 |

| Cortisone | 25 | 0.8 | 8−12 |

| Prednisone | 5 | 0.8 | 12−36 |

| Prednisolone | 5 | 0.8 | 12−36 |

| Methylprednisolone | 4 | 0.5 | 12−36 |

| Triamcinolone | 4 | 0 | 12−36 |

| Deflazacort | 6−7.5 | 0 | 12−36 |

| Long-acting | |||

| Betamethasone | 0.6 | 0 | 36−72 |

| Dexamethasone | 0.75 | 0 | 36−72 |

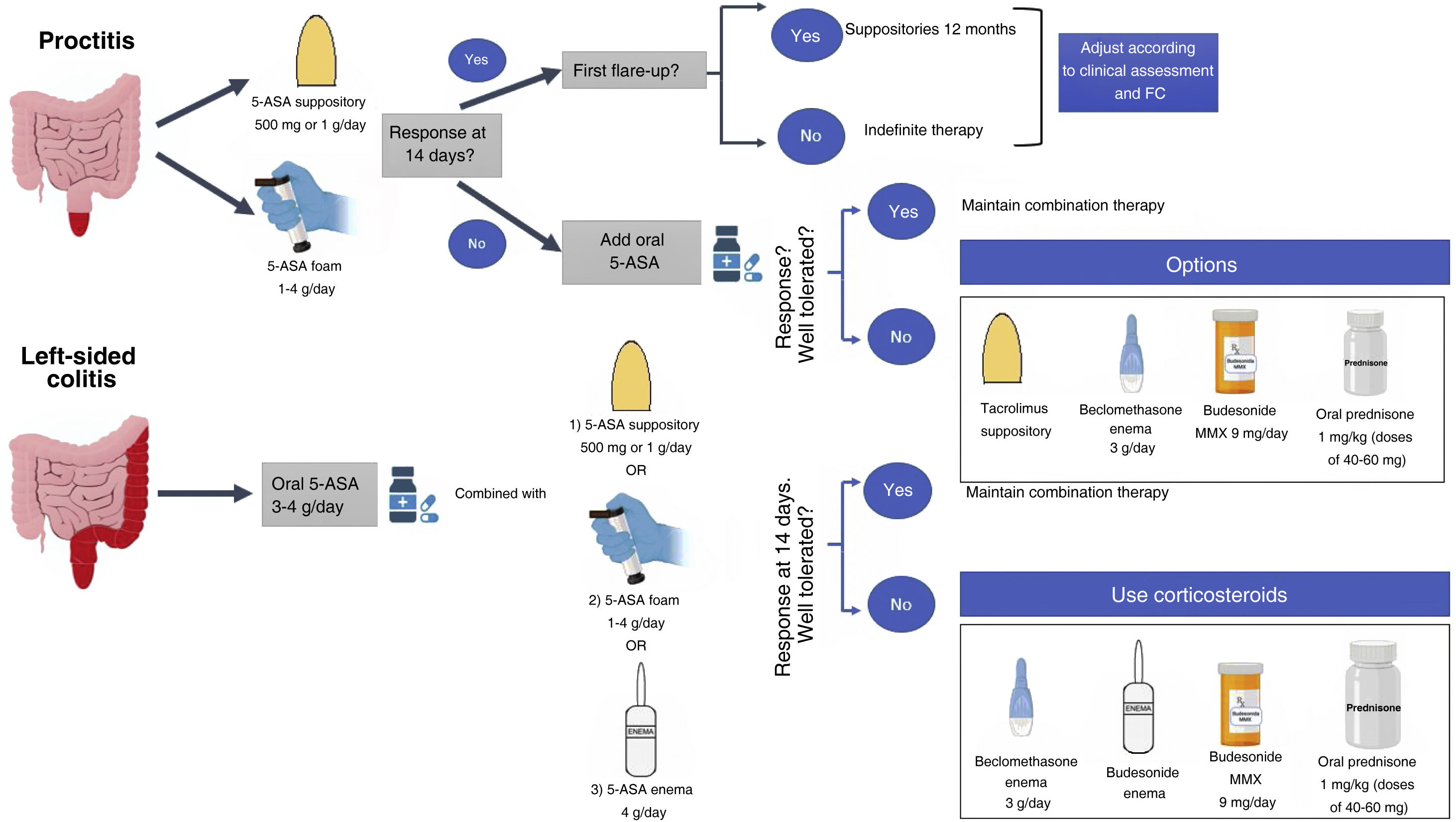

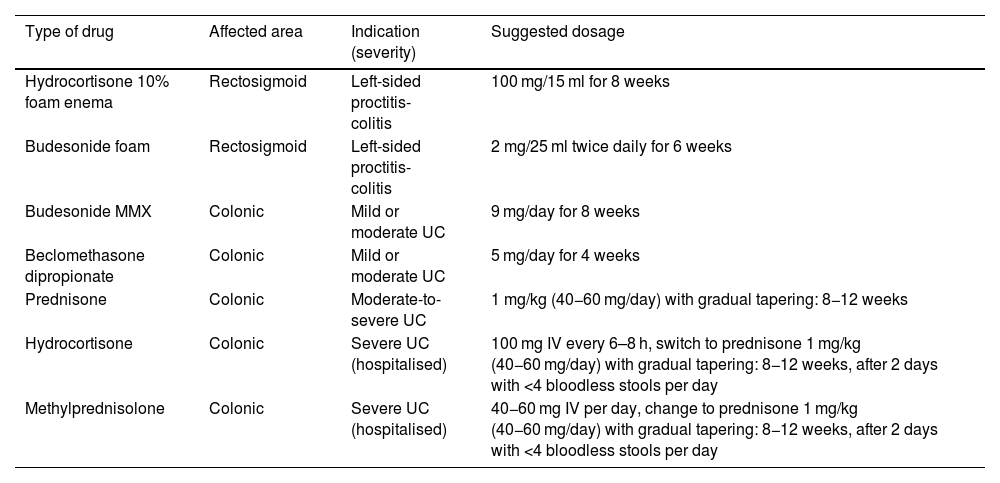

Several guidelines have indicated that, due to its greater effectiveness and patient tolerance, mesalazine should be the first option to induce remission in mild to moderate UC flare-ups, reserving oral or topical corticosteroids for cases refractory, allergic or intolerant to mesalazine7–9 (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Indications for the use of corticosteroids in ulcerative colitis.

| Type of drug | Affected area | Indication (severity) | Suggested dosage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrocortisone 10% foam enema | Rectosigmoid | Left-sided proctitis-colitis | 100 mg/15 ml for 8 weeks |

| Budesonide foam | Rectosigmoid | Left-sided proctitis-colitis | 2 mg/25 ml twice daily for 6 weeks |

| Budesonide MMX | Colonic | Mild or moderate UC | 9 mg/day for 8 weeks |

| Beclomethasone dipropionate | Colonic | Mild or moderate UC | 5 mg/day for 4 weeks |

| Prednisone | Colonic | Moderate-to-severe UC | 1 mg/kg (40−60 mg/day) with gradual tapering: 8−12 weeks |

| Hydrocortisone | Colonic | Severe UC (hospitalised) | 100 mg IV every 6–8 h, switch to prednisone 1 mg/kg (40−60 mg/day) with gradual tapering: 8−12 weeks, after 2 days with <4 bloodless stools per day |

| Methylprednisolone | Colonic | Severe UC (hospitalised) | 40−60 mg IV per day, change to prednisone 1 mg/kg (40−60 mg/day) with gradual tapering: 8−12 weeks, after 2 days with <4 bloodless stools per day |

UC: ulcerative colitis.

In mild to moderate left-sided UC refractory to adequate doses of mesalazine (topical and oral), adding topical corticosteroids in combination may provide a benefit. However, the evidence for adding topical corticosteroid to topical mesalazine is very limited.11 In 60 patients with left-sided UC it was found that the combined use of beclomethasone dipropionate enemas (3 mg/100 ml) and mesalazine enemas (2 g/100 ml) for 28 days was more effective in achieving endoscopic and histological improvement compared to each of these drugs as monotherapy (endoscopic improvement 100% vs. 75% vs. 71%, p = 0.021; histological improvement 0% vs. 50% vs. 48%, p = 0.009 for combination therapy, beclomethasone dipropionate and mesalazine monotherapy, respectively).11 However, the greater effectiveness of the topical corticosteroid/mesalazine combination has not been confirmed in ulcerative proctitis.12 Topical budesonide has been shown to have an adequate safety profile for inducing remission in patients with ulcerative proctitis or left-sided UC, even considering clinical effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.13 Given the tolerance to foam and the ease with which it can be applied, a higher percentage of patients prefer this route of administration.14 The use of hydrocortisone enema may be a strategy in patients with left-sided UC, but the adverse effects have to be considered.15

Systematic reviews have suggested the use of budesonide MMX (extended-release budesonide)16 and beclomethasone dipropionate17 in patients with mild to moderate UC who are intolerant to mesalazine or have a flare-up of inflammatory activity refractory to oral mesalazine at adequate doses (Fig. 1). A randomised controlled study involving 230 patients treated with budesonide MMX and 238 with placebo showed that a higher percentage of patients treated with this drug achieved the combination of clinical and endoscopic remission at eight weeks compared to placebo (13% vs. 7.5%, p = 0.049).18 A meta-analysis including 31 studies with a total of 5,689 patients showed that budesonide MMX was associated with fewer corticosteroid-related adverse events than with the use of systemic corticosteroids (OR: 0.25; 95% CI: 0.13−0.49).19 This lower systemic effect could avoid the side effects of corticosteroids, substantially reducing the economic cost of medical care in patients with mild to moderate UC.20 Subgroup analysis in the CORE I and CORE II studies showed that, compared to placebo, the efficacy of budesonide MMX in achieving clinical and endoscopic remission was significantly higher in left-sided UC but not in patients with extensive inflammatory activity.21,22 These results have been confirmed in a Cochrane meta-analysis.16 Importantly, other formulations of budesonide have not been shown to be effective in the treatment of UC, perhaps because of failure to achieve adequate distribution on the surface of the left colon.16 A systematic review including five randomised controlled studies with 888 patients with mild to moderate UC compared the effectiveness of beclomethasone dipropionate 5 mg/day to a group treated with mesalazine (4 studies) and prednisone (1 study).21 The results showed that after four weeks of treatment, beclomethasone dipropionate was more effective than mesalazine in inducing clinical remission (OR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.00–2.40; p = 0.05). Furthermore, beclomethasone would not be inferior to systemic prednisone in terms of clinical response and endoscopic cure, while maintaining an adequate safety profile.17 Studies conducted approximately five decades ago also demonstrated the superiority of prednisone over sulfapyridine in mild to moderate flare-ups of UC23,24 and it is an option in patients who are allergic, intolerant or refractory to mesalazine, or who do not respond to second generation, low-bioavailability corticosteroids (budesonide MMX or beclomethasone dipropionate).

Induction of remission in mild to moderate flare-up of Crohn's diseaseAs with UC, before prescribing corticosteroids to patients with CD, we should consider not only the severity of the flare-up but also the extent of the outbreak and the patient's history. With these prognostic factors and the top-down strategy, corticosteroids are prescribed less and less, and are only indicated at the start of a mild ileal or ileal-ascending colon flare-up or at the start of a moderate flare-up in any location associated with immunosuppressants (thiopurines or methotrexate) in patients with no risk factors.7,25

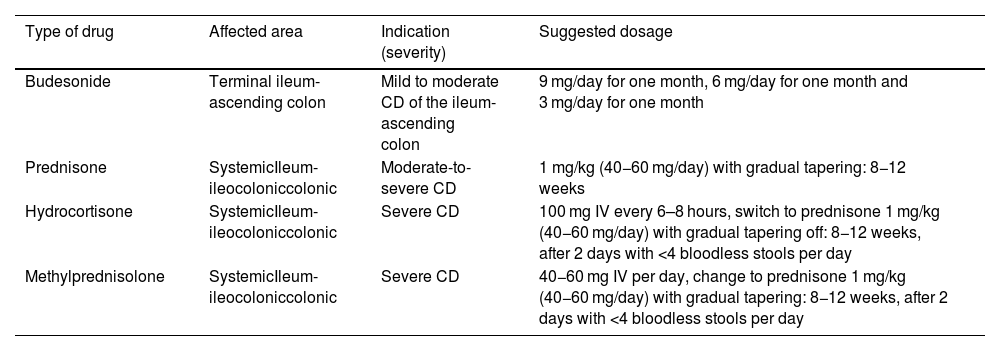

Although budesonide may be less effective than systemic corticosteroids, its better safety profile means it can be used in patients with ileal or ileal-ascending colon CD with mild to moderate inflammatory activity (Table 3).7,25 A Cochrane systematic review including three randomised controlled studies showed that in this setting budesonide was superior to placebo in inducing clinical remission (RR: 1.93; 95% CI: 1.37–2.73).26 This review, as well as a subsequent study involving 112 patients, showed that budesonide 9 mg is not inferior to mesalazine at doses of 3–4.5 g in achieving clinical remission in patients with ileal or ileocolonic CD.26,27 A study involving 201 patients with mild to moderate CD (100 patients treated with oral budesonide and 101 with systemic prednisone) showed that clinical remission was similar in both groups (51% and 52%, respectively). However, the development of adverse events was significantly lower in the budesonide-treated group (14% vs. 30%; p = 0.006).28 Despite these results, another study showed that only 11.5% of CD patients had been treated with budesonide in the first five years following diagnosis.29 Access to and the financial cost of these drugs may explain their under-utilisation.30 Although, to our knowledge, there are no studies of budesonide MMX or beclomethasone dipropionate in patients with colonic CD, their use could be considered in patients with mild inflammatory activity, thus avoiding adverse events to systemic corticosteroids.

Indications for corticosteroid use in Crohn's disease.

| Type of drug | Affected area | Indication (severity) | Suggested dosage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Budesonide | Terminal ileum-ascending colon | Mild to moderate CD of the ileum-ascending colon | 9 mg/day for one month, 6 mg/day for one month and 3 mg/day for one month |

| Prednisone | SystemicIleum-ileocoloniccolonic | Moderate-to-severe CD | 1 mg/kg (40−60 mg/day) with gradual tapering: 8−12 weeks |

| Hydrocortisone | SystemicIleum-ileocoloniccolonic | Severe CD | 100 mg IV every 6–8 hours, switch to prednisone 1 mg/kg (40−60 mg/day) with gradual tapering off: 8−12 weeks, after 2 days with <4 bloodless stools per day |

| Methylprednisolone | SystemicIleum-ileocoloniccolonic | Severe CD | 40−60 mg IV per day, change to prednisone 1 mg/kg (40−60 mg/day) with gradual tapering: 8−12 weeks, after 2 days with <4 bloodless stools per day |

CD: Crohn's disease.

In patients with CD having a mild to moderate flare-up, systemic corticosteroids (prednisone) could be considered in those with ileocaecal disease unresponsive to budesonide or in those with colonic disease who are allergic, intolerant or unresponsive to high-dose sulfasalazine.31,32

Induction of remission in moderate to severe flare-up of ulcerative colitisThe use of oral corticosteroids has been shown to be effective in inducing remission in moderate to severe UC and several guidelines have recommended their use.7–9 The first controlled study validating the use of corticosteroids versus placebo was published in 1955.1 This study, which included 103 patients, reported that 41.3% of cortisone-treated patients achieved clinical remission, compared to 15.8% in the placebo-treated group (p <0.001). A meta-analysis including five randomised controlled studies confirmed the effectiveness of systemic corticosteroids over placebo in inducing remission in UC patients (RR of remission: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.45−0.93), with a number needed to treat (NNT) of three.33 The starting dose of prednisone should be adjusted according to the patient's weight (1 mg/kg body weight), with a range of 40−60 mg per day (Table 2), assessing clinical response within the first seven days.8,34 Starting doses <15 mg have not been shown to be effective.33,35 Although doses >60 mg of prednisone have been shown to be effective, the benefits are not superior to those reported with doses from 40 to 60 mg.36 An Italian study showed that 22% of gastroenterologists used the starting dose of prednisone according to the patient's weight, while 50% used a fixed, predetermined dose, in most cases being 50−60 mg/day.37 Although guidelines recommend tapering prednisone gradually, the schedule to be used varies considerably, with the range being from eight to 12 weeks.7,8,33 This uniformity in corticosteroid withdrawal has also been observed in different clinical studies.5,38 The rate of tapering of the dose of this drug should be guided by how clinical symptoms evolve, cumulative corticosteroid exposure and the onset of action of therapies to be used to maintain remission (mesalazine, thiopurines, biological therapy and small molecules). One study showed that only 40% of gastroenterologists use a personalised regimen defined by patient characteristics.37 Although the gradual corticosteroid tapering regimen used does not seem to alter patient outcomes,39 we do think it is important to stress two points. Firstly, to start tapering, the patient should be in remission in terms of symptoms, and this usually occurs within the first one to two weeks. However, the full dose could be maintained for a third week. On the second point, the corticosteroid should, if possible, not be continued beyond 12–16 weeks, and alternatives should be sought in this scenario.

Induction of remission in severe flare-up of ulcerative colitisEither at onset or during the course of their disease, approximately 25% of UC patients will develop an episode of severe inflammatory activity with systemic manifestations and gastrointestinal symptoms that may be life-threatening, with a possible need for surgery.40 Initial management with intravenous (IV) corticosteroids remains the first choice, changing the natural history of untreated severe UC with a decrease in mortality from 24% to 7%.41,42 The drugs suggested in this scenario are hydrocortisone 100 mg every 6–8 hours or methylprednisolone 40−60 mg per day (Table 2).7,38 Methylprednisolone could be used as a first choice in patients with hypokalaemia, given its lower mineralocorticoid effect compared to hydrocortisone.43 However, about 30%–40% of patients with severe UC have a partial response or do not respond to IV corticosteroids, with colectomy rates ranging from 25% to 30%44, rates that have remained unchanged despite the introduction of biologicals. The protocolised and multidisciplinary management of this condition with early (day 3–5) assessment of corticosteroid response and the use of second-line rescue therapies has improved the prognosis of these patients.7–9 A recently published retrospective cohort including 50 episodes of severe UC reported that 88% of flare-ups were treated with IV corticosteroids as first-line therapy (median: 3 days; range: 1–7); 59% progressed favourably, without a new flare-up or the need for hospitalisation or colectomy within three months.45 However, it is important to consider that prior exposure to corticosteroids may affect the effectiveness of this first-line therapy. This study showed that patients with no prior IV corticosteroid exposure had a greater response to corticosteroids than the group with a history of prior corticosteroid use (100% vs. 19%, p = <0.001).45 These results suggest that in this group of patients, the treatment of severe flare-ups should be started directly with some second-line strategy (calcineurin inhibitors, infliximab or surgery). Another cohort, with 26% of patients exposed to biological therapy (19% anti-TNF and 7% anti-integrins), reported that 41% were refractory to corticosteroids applying Oxford criteria, with an increased risk of colectomy in this group of patients versus those not exposed to biological therapy (32% and 16%, respectively).46 These results should be confirmed in further studies in order to help personalise the treatment of severe UC. In view of this evidence and these rates, we need to think twice about using IV corticosteroids in severe UC flare-ups in patients who have already had a severe flare-up rescued with IV corticosteroids or who have had exposure to or are being treated with biological therapy. It is important to be aware that, unlike anti-TNF biological therapy, the use of corticosteroids has been associated with an increased risk of venous and arterial thromboembolism in patients with IBD.47–49 This risk has to be considered when deciding between the use of corticosteroids or infliximab for the management of severe UC.

Finally, if from days three to five there is a favourable response to IV corticosteroid treatment, it should be maintained until the patient has fewer than four bloodless stools per day for two consecutive days. Once this scenario is reached, parenteral corticosteroids can be switched to oral prednisone 1 mg/kg (total dose range 40−60 mg) with gradual tapering off. If the severe flare-up has responded to corticosteroids and the patient is naïve to all treatment (for example, onset), one option is to start thiopurines. Mesalazine could also be a strategy in this setting, particularly in patients with a rapid response to corticosteroids.9 However, its success rate at six months is below 20% and these patients would therefore have to be closely monitored so that a rescue pathway could be activated quickly if there was evidence of inflammatory activity. In patients who have a partial response or do not respond to IV corticosteroids, it is necessary to consider second-line or rescue therapies, such as the use of calcineurin inhibitors (ciclosporin or tacrolimus) or biological therapy with infliximab.40

Induction of remission in moderate to severe flare-up of Crohn's diseaseOral systemic corticosteroids may be indicated in patients with moderate-to-severe CD and IV systemic corticosteroids in severe CD (Table 3).7,25 However, considering the new therapeutic options (anti-TNF, anti-p-40 IL-12/23 and anti-integrin biological therapy) and the effectiveness of the top-down strategy, corticosteroids should only be prescribed at the onset of a moderate flare-up at any site in combination with immunosuppressants (thiopurines or methotrexate) in patients without risk factors.

The prednisone dose and tapering-off schedule are similar to those described in patients with UC. Recently, a meta-analysis including 14 controlled studies (4,354 patients) suggested that the combination of corticosteroids and an anti-TNF would not increase the likelihood of achieving clinical remission compared to the use of this biological medicine in monotherapy (32% vs. 35.5%, respectively; OR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.74–1.17),50 again suggesting that the use of corticosteroids would not be indicated in patients already on immunosuppressive treatment or who needed to start biological therapy, and would only increase morbidity.

Induction of remission in pouchitisProctocolectomy with ileoanal pouch is the surgical treatment of choice in UC patients refractory to various drugs.51,52 Although this strategy improves patients' quality of life and maintains the defecatory route (compared to permanent ileostomy), it is not without anatomical or inflammatory complications over time.51 Oral or topical budesonide has been suggested in different scenarios in patients with pouchitis. Topical budesonide can be an option in patients with acute pouchitis. A randomised study involving 26 patients with acute pouchitis showed that budesonide in enemas (2 mg/100 ml) for six weeks has the same clinical efficacy as metronidazole 500 mg twice daily (58% vs. 50%). However, the occurrence of adverse events was lower in the group treated with topical budesonide (25% vs. 57%).53 A study involving 20 patients with chronic pouchitis who had failed to respond to one month of antibiotic therapy showed that classic budesonide at a dose of 9 mg for eight weeks is effective in achieving clinical remission and improving quality of life in patients with chronic pouchitis refractory to antibiotics.54 Other authors have also shown the effectiveness of budesonide in inducing and maintaining remission in patients with chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis.55 Although studies are needed to confirm its effectiveness, oral budesonide has been suggested as remission induction therapy in patients with CD-related pre-pouch ileitis or pouchitis.51 Topical corticosteroids can be used to induce remission in patients with cuffitis (rectal remnant) that does not respond to topical mesalazine. In a study involving 120 patients with cuffitis, treatment with mesalazine and/or topical corticosteroids was effective in 33.3% of patients, with 18.3% being dependent on these two treatments.56

Errors in the use of corticosteroidsA number of authors have argued that corticosteroid use should be an indicator of quality of care in IBD programmes.57–60 Despite this suggestion, a significant proportion of patients are still inappropriately treated with corticosteroids.61–64 A study involving 16,512 patients with UC showed that 41% of patients received at least one prescription of oral corticosteroids. In patients with CD, 57% received corticosteroids at least once within five years of diagnosis.63 We believe that the main errors that need to be eradicated in the management of IBD patients are as follows:

- •

Error 1: "maintenance corticosteroids", either because they are not discontinued or because they are often prescribed without a maintenance therapy strategy. There is sufficient information to indicate that corticosteroids have no indication as maintenance therapy in IBD7–9,65 and should not be prescribed given the short-, medium- and long-term adverse events (Table 4).5,66 Despite this suggestion, one study showed that of the 9,456 patients with UC diagnosed between 2002 and 2010, 13% had had very prolonged exposure (>6 months) to corticosteroids and 17.8% had received repeated exposure to these drugs (further corticosteroid use within three months of the end of previous treatment). Of the 4,274 patients with CD diagnosed during the same period, 24.6% had had very prolonged exposure and 31.3% had received repeated exposure to corticosteroids.63 Other authors have also confirmed prolonged and repeated exposure to systemic corticosteroids in patients with IBD.67 A multicentre study auditing the treatment of 1,176 patients with IBD showed that 14.9% met criteria for corticosteroid dependence or overuse of corticosteroids. More importantly, 50% of the prescriptions were entirely avoidable.67

Table 4.Adverse events to corticosteroids.

Short-term effects Long-term effects Effects post-discontinuation • Increased appetite• Weight gain• Sleep and mood disorders• Dermatological: acne, moon face, oedema, hirsutism• Glucose intolerance • Posterior subcapsular cataract• Osteoporosis• Osteonecrosis of the femoral head• Myopathy• Increased susceptibility to infectionArterial hypertension • Acute adrenal insufficiency• Pseudorheumatism• Increased intracranial pressure Source: Grennan and Wang.66

Care by a non-specialist physician, self-medication, challenges in the treatment of patients aged >65 years of age and the use of thiopurines in UC and mesalazine in CD have all been associated with corticosteroid dependence or overuse of systemic corticosteroids.67–69

Various guidelines have defined corticosteroid dependence as the inability to reduce the dose of prednisone to <10 mg/day (or budesonide below 3 mg/day) within three months of starting corticosteroids, without recurrent active disease or relapse within three months of stopping these drugs.7,52,70 In this scenario, it is necessary to consider the early introduction of corticosteroid-sparing agents, such as immunomodulators (thiopurines and methotrexate), biological therapy (anti-TNF, anti-integrin, anti-p40 IL-12/23) or the use of small molecules (Janus kinase inhibitors and sphingosine-1-phosphate agonists).

- •

Error 2: using corticosteroids in patients who are ALREADY being treated with immunomodulators or combined with biologicals. Little evidence is available in this specific scenario, and in fact, in clinical trials of new drugs, 30–40% of patients are started on corticosteroids. A meta-analysis involving 4,354 patients suggested that the combination of corticosteroids and an anti-TNF alone would increase morbidity due to adverse events.50 There is no evidence regarding the efficacy of using corticosteroids when the patient is already on immunosuppressive treatment without moving up a therapeutic step or avoiding surgery. Only one retrospective study provides figures of 35% effectiveness in this scenario.4 This study also analyses the efficacy of topical corticosteroids as a drug with fewer side effects in patients with UC treated with immunomodulators, without finding differences in success rates.

- •

Error 4: Believing that corticosteroids are safer in patients aged >65 and not using biological medicinal products in this subgroup. A study involving 393 patients with IBD aged >65 showed that 31.6% had been treated with prednisone for a period ≥ six months. Despite the availability of biological therapy, the use of systemic corticosteroids increased from 36.3% in the period 1991–2000 to 63.7% in the period 2001–2010.71 Other authors have also confirmed the high percentage of patients aged >65 exposed to long-term corticosteroid use.72 In this group of patients, only a small proportion received immunomodulatory treatment or biological therapy (39.5% and 21.1%, respectively). As the safety and effectiveness of different biological medicinal products has been demonstrated in patients with IBD aged >6573 and that the rate of adverse events due to prolonged corticosteroid use is higher than with biological therapy,74,75 the therapeutic approach in this patient group should be modified.

- •

Error 5: Lack of knowledge about complications associated with the use of corticosteroids and their treatment. The treating team must consider not only the dose and duration of corticosteroid treatment, but also events secondary to its use (Table 4).5,66 IBD is associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures. These extraintestinal manifestations are the result of changes in bone emodeling secondary not only to the use of corticosteroids, but also to the immunological alterations that lead to the development and progression of IBD.76 A systematic review including 12 studies showed that the prevalence of osteoporosis in patients with IBD is 4%–9%, and is higher in CD (7–15% CD vs. 2–9% in UC).77 Bone mineral density loss may increase with corticosteroids, by as much as 22.6% in patients with CD treated with these drugs.78 Bone mineral density can be significantly improved with vitamin D and calcium intake.79 All patients with IBD on corticosteroids, including low‐bioavailability oral corticosteroids, should receive 800−1,000 mg of calcium and 800 IU of vitamin D.7 Despite this, a study involving 131 gastroenterologists showed that only 38% prescribed vitamin D and calcium for these patients. The rate is even lower in patients over40 years of age (31% in over-40 s vs. 49% in under-40 s; p = 0.037.37

Corticosteroid use may increase the need for hypoglycaemic drugs by a factor of two compared to the population not exposed to steroids.80 It seems prudent, therefore, for this risk be assessed before starting steroid treatment. It should be remembered that the risk of hypoglycaemia associated with these drugs is higher in older adult patients81; a further argument for not considering corticosteroids as a suitable drug to give these patients in an attempt to avoid the presumed adverse events of biological therapy and small molecules.

Psychiatric adverse events are common in patients on corticosteroids.82 This is important as recent studies have confirmed that IBD patients have high psychiatric comorbidity, which can affect their quality of life.83

Although a discussion of all corticosteroid-related adverse events is beyond the scope of this review (Table 4), it seems prudent to mention that in the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, systemic corticosteroids are the only drugs used in the management of IBD found to have a negative effect in the COVID-19 pandemic.84 For that reason, the treating team should try to avoid the use of systemic corticosteroids to induce remission, prioritising other therapies such as mesalazine, budesonide, biological therapy and small molecules.

In conclusion, corticosteroids continue today to be part of the management of patients with IBD. However, with the currently available therapeutic arsenal, in CD, it seems reasonable to reconsider the need to use corticosteroids beyond the first flare-up. We really need to consider whether it might be more appropriate to start treatment directly with the new drugs and leave corticosteroids for the rescue of some patients with more refractory disease. In UC, strict control of corticosteroid dependence is necessary, at least avoiding the use of systemic corticosteroids in patients already on immunomodulators. With this in mind, it seems wise to argue that the appropriate use of these drugs should be considered an indicator of quality of care in patients with IBD. It is this approach that will help us to change the course of IBD and with it the quality of life of these patients (Fig. 2).

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed equally to this review: study conception and design; literature review and analysis; writing; critical review and editing; and approval of the final version.