To the editor: Hepatoportal sclerosis (HS) is an idiopathic noncirrhoticintrahepatic portal hypertension characterized by splenomegaly, hypersplenismand portal hypertension. Although it is considered uncommonin developed countries there is an increasing number of cases reportedwhich could traduce a better knowledge of this disease and a higher levelof suspicion. Our objective is to report a case of HS emphasizingdiagnosis and the long-term evolution

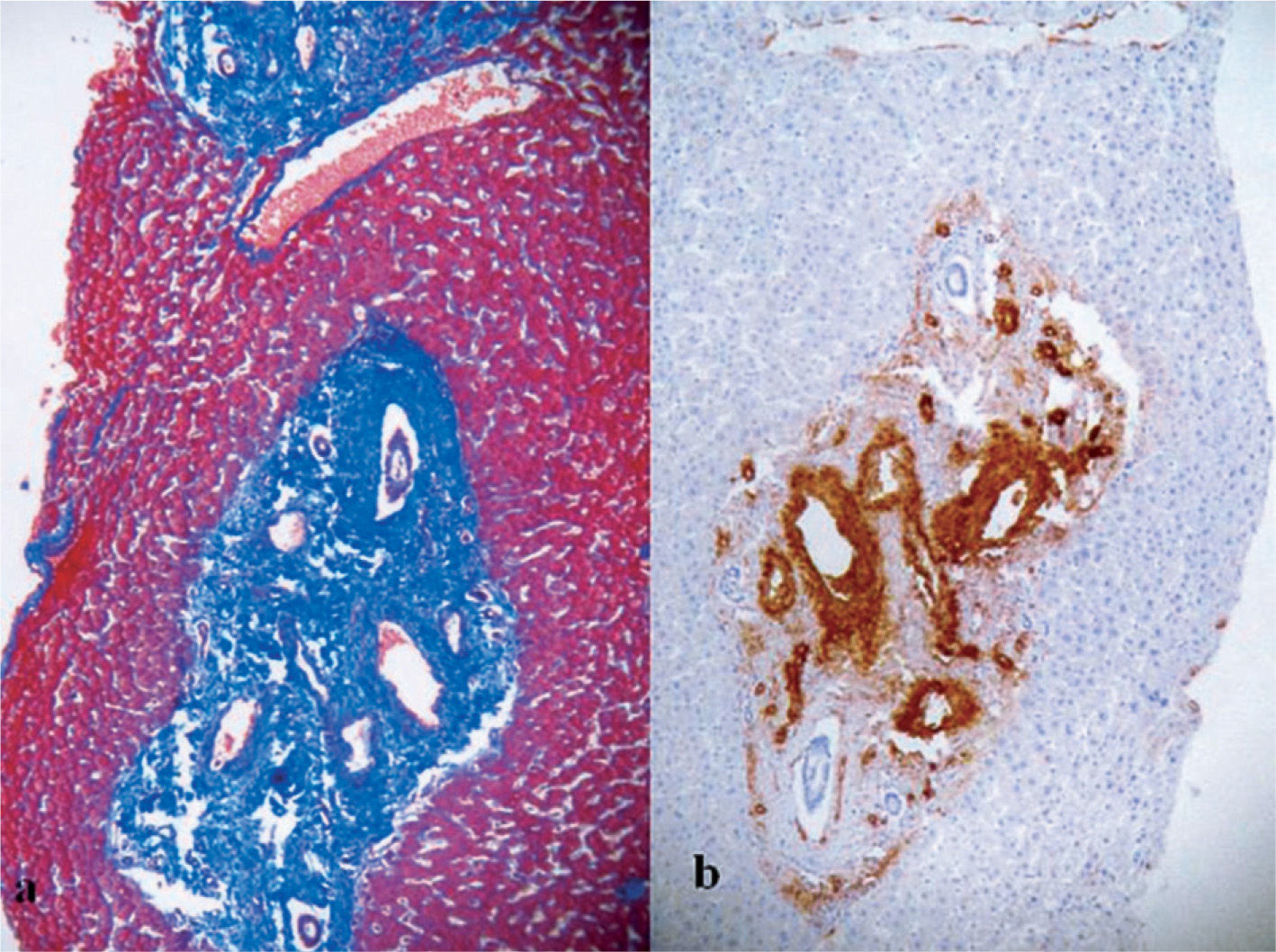

A 47-year-old man was referred in 1992 to our institution to study abicytopenia detected in the course of the study of epigastric complaints;he admitted a low ethanol intake (< 30 g/day). His medical history onlyincluded a left glaucoma under topic treatment with latanoprost. Laboratorytests revealed low leukocyte (3,400/μl; normal range, 4,500-11,000) and platelet (59,000/μl; 150,000-350,000) counts without anaemia.Coagulation and biochemical tests including liver function tests(LFTs) and serum proteins were normal. The upper endoscopy showeda mild portal gastropathy, little esophageal varices and an Helicobacter pylori positive duodenal ulcer. Chronic infection by hepatotropic viruseswas discarded and a screening of other frequent causes of chronic liverdamage did not reveal infectious, autoimmune or metabolic diseases.A hypercoagulable state was discarded. A Doppler ultrasoundrevealed a normal liver echotexture, size and surface without portalvein thrombosis, splenomegaly and collateral vessels showing portalhypertension (PH). A percutaneous liver biopsy was then performedshowing portal fibrosis without cirrhosis (fig. 1). Finally, a haemodynamicassessment revealed a near-normal hepatic venous pressure gradientof 7 mmHg (free suprahepatic pressure: 9.0 mmHg and wedgedsuprahepatic pressure: 16.0 mmHg). A diagnosis of HS was done. Hebecame asymptomatic after Helicobacter eradication and refused follow-up. Fifteen years later, follow-up has been resumed; he feels welland no liver decompensation has occurred. Laboratory tests show lowleukocyte (4,100/μl) and platelet (59,000/μl) counts without anaemia,and a preserved liver function. Endoscopy findings are unchanged and acomputerized tomography reveal liver atrophy, no portal thrombosis,signs of PH with an open splenorenal shunt, patent portal vein and splenomegaly(fig. 2). Primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding has beeninitiated

Histological appearance of hepatoportal sclerosis. a) The intrahepatic portal tracts are markedly fibrosed and expanded (Masson stain) with normal parenchymal surrounding, and b) immunohistochemical stain with anti-smooth muscle antibodies showing aberrant portal vessel with marked medial muscular hypertrophy.

HS is a non-cirrhotic presinusoidal intrahepatic PH. Other names thatseem synonymous include idiopathic portal hypertension (IPH), Banti’sdisease, non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis, obliterative portal venopathy, noncirrhoticintrahepatic portal hypertension and idiopathic presinusoidalportal hypertension1,2. IPH has been reported mainly in India and Japanbeing uncommon in Occident where, notwithstanding, new cases arecontinuously reported3–5. The diagnostic criteria include splenomegaly,normal to near-normal LFTs, demonstrable varices, decrease of one ormore of the formed blood elements, liver scan not typical of cirrhosis,patent portal and hepatic veins with elevated portal pressure and a normalto slightly elevated wedged hepatic venous pressure, and markedportal fibrosis with no diffuse nodule formation. Although not all of thesecriteria are necessary, PH must be unequivocal with absolute exclusionof cirrhosis, schistosomiasis, and the occlusion of the hepatic andportal veins1–5. The exact cause of IPH is still obscure and toxic, autoimmuneor infectious theories have been postulated. Although it usuallyhas a benign course, liver atrophy, cirrhosis and even liver failure canoccur in latter phases of the disease. In fact, some cases of liver transplantationhave been performed in patients with end-stage liver diseaseattributed to a putative cryptogenic cirrhosis that have ultimately resulted in a diagnostic of HS after examining the explanted liver; hence, ithas been postulated that this entity could often go unrecognised5. Primaryprophylaxis of variceal bleeding could be helpful to prevent complicationsand if bleeding occurs, endoscopic and/or a portosystemicshunt are appropriate. We report a new case of HS that increases the casuistryof this entity in our area; it shows a long-term benign course withoutbleeding nor variceal progression perhaps favoured by a splenorenalshunt. Fifteen years after the initial diagnosis, there is a severehepatic atrophy, probably due to chronic hypoperfusion, and we can notdiscard newly developed secondary cirrhosis (the patient reject new invasivestudies); hence, he might be now misdiagnosed as having a cryptogeneticcirrhosis if there were no previous studies. Although hepatoportalsclerosis is not a prevalent cause of portal hypertension inOccident, it must be considered mainly when PH appears without evidenceof cirrhosis, portal occlusion or schistosomiasis.