Endoscopic resection is the common treatment in pT1 colorectal adenocarcinoma whenever possible. The presence of adverse histological factors requires subsequent lymph node evaluation.

Materials and methodsWe selected 29 colorectal pT1 adenocarcinoma including endoscopic polypectomies and the corresponding surgical specimens. All histologic parameters associated with N+ were evaluated by 2 pathologists, including: tumour differentiation grade, depth of invasion in the submucosa, angiolymphatic invasion (ALI), perineural invasion, chronic inflammation, tumour budding, poorly differentiated cluster, pre-existing adenoma, tumour border, and endoscopic resection margin. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the individual capacity of each variable to predict N+.

ResultsIn the univariate analysis, rectal tumour localization, ALI and poorly differentiated cluster were significantly associated with N+. Among the significant parameters, ALI had the highest area under the ROC curve (0.875). Multivariate analysis showed no independent variables associated with N+.

ConclusionsWe confirm that ALI and the presence of poorly differentiated cluster are frequently associated with N+ in early colorectal cancer. Consequently, these parameters should be routinely evaluated by pathologists.

El tratamiento habitual del adenocarcinoma colorrectal pT1 consiste en la resección endoscópica siempre que sea posible. Se requiere la evaluación de los ganglios linfáticos locorregionales cuando se detectan factores histológicos adversos en las polipectomías endoscópicas.

Materiales y métodosSe seleccionaron 29 adenocarcinomas colorrectales pT1 incluyendo las polipectomías endoscópicas y piezas quirúrgicas correspondientes. Se evaluaron por 2 patólogos todos los parámetros histológicos asociados a N+, incluyendo: grado de diferenciación tumoral, profundidad de invasión en submucosa, invasión angiolinfática (IAL), invasión perineural, inflamación crónica, gemaciones tumorales, grupos de tumor pobremente diferenciados, adenoma preexistente, borde tumoral y margen de resección endoscópico. Se realizó un análisis de regresión logística univariante y multivariante para evaluar la capacidad individual de cada variable para predecir N+.

ResultadosEn el análisis univariante, la localización rectal, la presencia de IAL y la presencia de grupos de tumor pobremente diferenciados se asociaron significativamente con metástasis ganglionares. De todas estas variables, la presencia de IAL presentó la mayor área bajo la curva ROC (0,875). El análisis multivariante no encontró ninguna variable independiente asociada a N+.

ConclusionesLa IAL y la presencia de grupos de tumor pobremente diferenciados se asocia frecuentemente con N+ en cáncer colorrectal precoz, por lo que se debe implementar rutinariamente la evaluación de estos parámetros histológicos.

Despite major advances in the multidisciplinary treatment of colorectal cancer (CRC), local and/or systemic recurrence remains one of the major problems of this tumour group.1–12 The presence of loco-regional lymph node metastases is considered one of the main prognostic factors associated with local and/or distant recurrence, so it is important to assess the risk of lymph node involvement, especially in patients who are candidates for local resection, and particularly in tumours that invade the submucosa (T1).1–22

The efficacy of current methods for early CRC detection has increased diagnosis in incipient phases, particularly of adenocarcinoma (ADC) in situ or pT1 ADC.1,9–13 Most T1 tumours can be treated using local resection techniques (endoscopic or surgical), providing that clinical, radiological and/or pathological parameters enable the risk of lymph node metastasis to be determined, especially when additional surgery with loco-regional lymph node resection is not scheduled.1–13

Considering that the incidence of lymph node metastases in pT1 tumours oscillates between 8% and 16%, additional surgery with lymph node resection would only benefit a small percentage of cases.2–22 Moreover, a large number of patients would undergo risky surgical intervention for no purpose, as affected lymph nodes may not be found.10–15 On the other hand, given that post-operative complications have been reduced with current advances in surgery and post-operative care, performing this further procedure could have the advantage of yielding the correct T and N pathological stage that would inevitably aid subsequent decision making.1–10

Unfortunately, as far as we are aware, there are no clinical or molecular factors that can predict loco-regional lymph node metastases in pT1 tumours. Although radiological studies theoretically provide additional information on lymph node staging, there are no well defined criteria that can definitively confirm this type of metastasis.1–5 A recent study has been implemented of histopathological factors in polypectomy specimens that might predict the risk of loco-regional lymph node metastases and which therefore would facilitate decision making as regards further surgical treatments.1–22

According to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines and World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumours, the presence of a poorly differentiated histological grade G3 tumour and angiolymphatic invasion (ALI), respectively, are the only histological factors which, when present, are indicative of further surgery in T1 CRCs with margin-negative endoscopic resection.23 However, a proportion of patients present lymph node metastases even without poor tumour differentiation or ALI in the polypectomy specimen. According to European (ESMO)24–30 and Japanese (JSCCR) guidelines,31 other histological parameters, when present, are indicative of further surgery. These factors include the presence of tumour budding (TB) and submucosal invasion deeper than 1mm. A new histological factor has recently been described, called poorly differentiated clusters (PDCs), which significantly and more reliably predicts the risk of lymph node metastases in T1 CRCs.1–22 However, many of these histological factors are not generally described in histopathology reports, and as has been shown in some studies, reproducibility and standardization are inadequate, especially in regard to TB, PDCs and submucosal invasion depth.1–15

The aim of this study was to evaluate the histological parameters described as predictive of loco-regional lymph node metastases in a series of cases diagnosed with stage pT1 CRC, in order to determine which parameters were more often associated with the presence or otherwise of lymph node metastases.

Materials and methodsThe study included 29 patients with pT1 colorectal ADC, diagnosed between 2006 and 2014 in the Department of Pathology of the Valencian Institute of Oncology, for whom slides and/or paraffin blocks were available for histopathology analysis. The samples came from endoscopic polypectomies in which infiltrating ADC (pT1) had been diagnosed as well as the corresponding additional surgical specimen, which included mesocolic and mesorectal lymph nodes. Also included in this group were patients diagnosed with T1 ADC for whom no previous endoscopic polypectomy was available and who had been operated directly because the polyps were considered to be endoscopically unresectable. None of the patients had received neoadjuvant treatment. Patients with previous endoscopic polypectomies were operated due to the presence of one or more of the following findings: positive or non-assessable endoscopic resection margin, G3 tumours, presence of ALI, TB or PDCs, and submucosal invasion depth greater than 1mm. The pathological stage was established according to the TNM-7 system.15 Only patients in whom at least 12 lymph nodes were analyzed, in accordance with conventional standards, were included, to ensure that the surgery and pathology reports were correct. Tumours were grouped according to location as originating in the colon (ascending, transverse, descending or sigmoid) or rectum (upper, middle or lower thirds).

Study procedures were in accordance with the regulations approved by the Valencian Institute of Oncology's local institutional review board.

After fixing the surgical specimen with formaldehyde, histological sections of the tumour (polyp sample and surgical specimen) and lymph nodes (surgical specimen) were cut and embedded in paraffin. Next, 2–5μm histological sections were cut and stained with haematoxylin–eosin (HE) for initial histopathological evaluation. All the slides stained with HE were analyzed for the following histological parameters: tumour differentiation grade (according to WHO 2010 histological criteria regarding gland formation in the tumour, as follows: G1: >95%; G2: 50–95%; G3: 5–50%; G4: <5%), depth of submucosal invasion from the muscularis mucosa (less than or greater than 1mm), ALI and perineural invasion (PNI) (present, absent), chronic peritumoral inflammation (mild, moderate, severe), TB (present, absent), PDCs (present, absent), pre-existing adenoma (present, absent), tumour border (infiltrative or expansive) and endoscopic resection margin for the endoscopic polypectomies of pT1 tumours (free or affected). A margin was considered to be affected when the tumour touched it or when the tumour-to-margin distance was less than 1mm. The presence or absence of lymph node metastases in the surgical specimen was also evaluated. Although some of these factors had already been analyzed by a pathologist in the inital pathology report, all the histological parameters were re-evaluated independently by two pathologists (IM and JC) and by a biotechnology graduate grant-holder on rotation in our department (MVA).

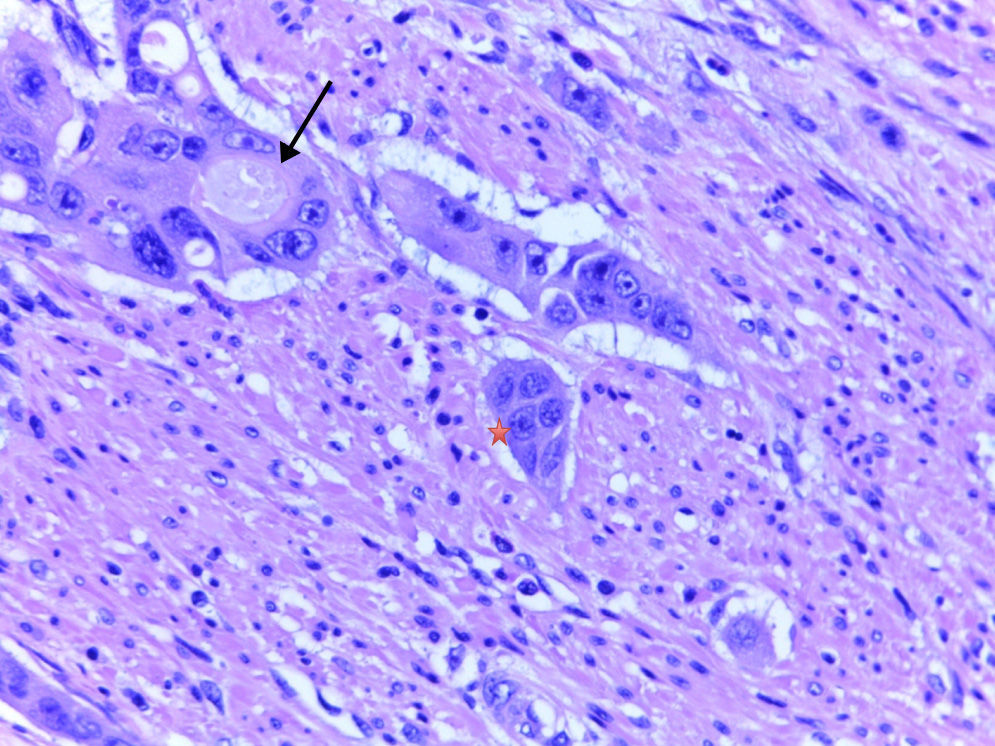

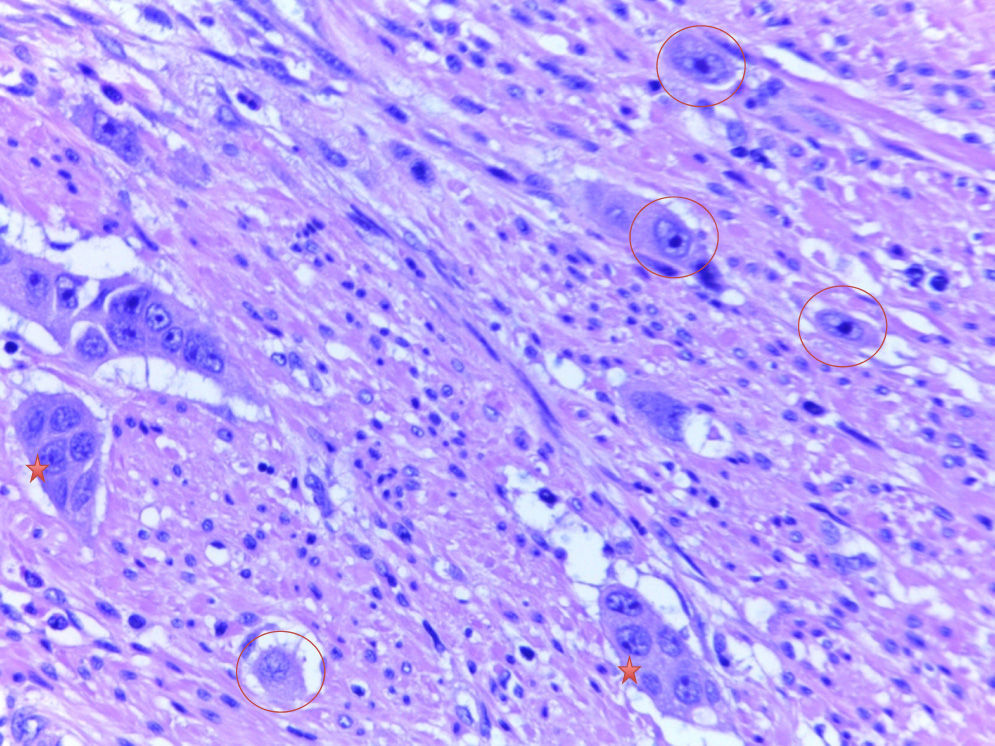

DefinitionsTumour buddingTB is defined as single tumour cells or clusters of fewer than 5 cells isolated from the tumour.2–10 The histological samples analyzed with HE staining were imaged at 40× magnification in a Leica DM2000 microscope and classified according to the presence or absence of TB.

Poorly defined clustersAccording to the definition established by Ueno et al.2–4 and applied by Barresi et al.,5–8 PDCs are isolated clusters of 5 or more tumour cells that lack an identifiable glandular lumen and that are isolated from areas of necrosis or tumour gland fragmentation due to ulceration or inflammation. In order to quantify the PDCs, each slide was initially analyzed at 10× magnification in order to identify regions with a significant number of PDCs. A higher magnification (40×) was then used to count the clusters. The PDCs were counted as the number of clusters present (<5, 5–9 and ≥10), as per previous studies.7,8 To facilitate the statistical analysis, and considering the low number of cases, the tumours were classified taking into account only the presence or absence of PDCs.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed to determine the distribution of clinical (location and TNM stage) and histological variables. Clinical and pathological characteristics were analyzed to obtain frequency and percentage values. Univariate logistic regression analysis was carried out to evaluate the capacity of each variable to predict the likelihood of lymph node metastasis (N+). Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals were also calculated. The associated p values were used to predict the significance level of the histological parameters. The predictive capacity of the model—the precision with which the histological parameters could predict the presence or absence of nodal metastasis—was indicated by the area under the ROC curve (AUC), and confidence intervals and the corresponding p values were also considered. Multivariate analysis of the statistically significant factors in the univariate analysis aimed to identify any variable(s) that independently contributed to the development of nodal metastasis. The p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS® software, version 20.

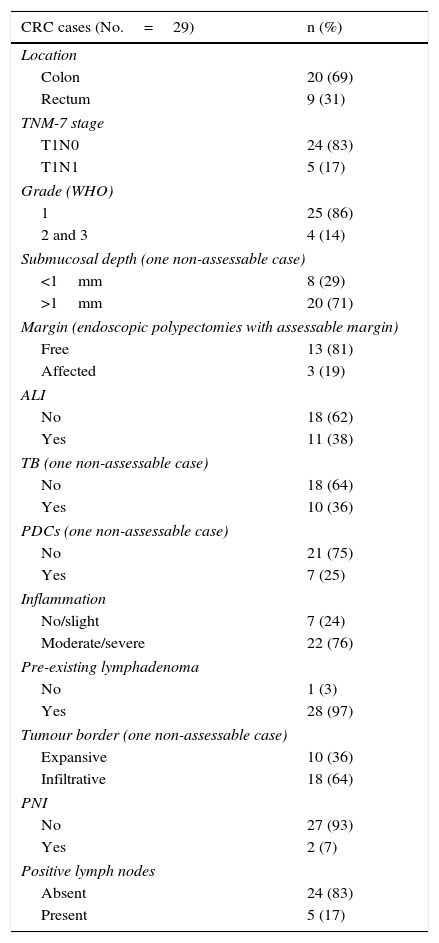

ResultsA total of 29 patients (19 men and 10 women, mean age 63 years) with pT1 colorectal ADC were included. Polyp samples and the corresponding surgical specimens (when one or more adverse histological factors were found on polypectomy) were available for 21 patients, while surgical specimens only were available for the remaining 8 patients in whom the T1 tumours were initially considered unresectable. Clinical and pathological characteristics are shown in Table 1. Lymph node metastases were detected in 5 patients during follow-up, as recorded in the medical records.

Clinical and pathological variables in pT1 tumours.

| CRC cases (No.=29) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Colon | 20 (69) |

| Rectum | 9 (31) |

| TNM-7 stage | |

| T1N0 | 24 (83) |

| T1N1 | 5 (17) |

| Grade (WHO) | |

| 1 | 25 (86) |

| 2 and 3 | 4 (14) |

| Submucosal depth (one non-assessable case) | |

| <1mm | 8 (29) |

| >1mm | 20 (71) |

| Margin (endoscopic polypectomies with assessable margin) | |

| Free | 13 (81) |

| Affected | 3 (19) |

| ALI | |

| No | 18 (62) |

| Yes | 11 (38) |

| TB (one non-assessable case) | |

| No | 18 (64) |

| Yes | 10 (36) |

| PDCs (one non-assessable case) | |

| No | 21 (75) |

| Yes | 7 (25) |

| Inflammation | |

| No/slight | 7 (24) |

| Moderate/severe | 22 (76) |

| Pre-existing lymphadenoma | |

| No | 1 (3) |

| Yes | 28 (97) |

| Tumour border (one non-assessable case) | |

| Expansive | 10 (36) |

| Infiltrative | 18 (64) |

| PNI | |

| No | 27 (93) |

| Yes | 2 (7) |

| Positive lymph nodes | |

| Absent | 24 (83) |

| Present | 5 (17) |

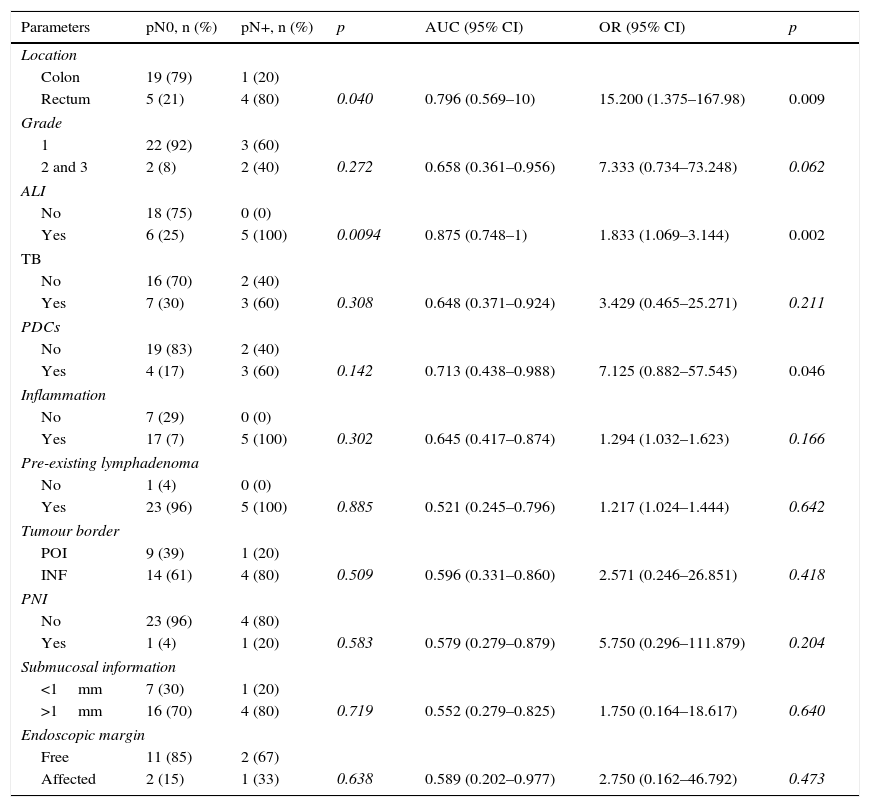

Table 2 shows results for the univariate and multivariate analyses, which evaluated the capacity of each variable to predict lymph node metastasis and the precision with which each clinical and histological parameter was able predict the presence/absence of nodal metastasis, as reflected by the AUC. In the univariate analysis, rectal location (p=0.009), ALI (p=0.002) and presence of PDCs (p=0.046) were significantly associated with lymph node metastases. The presence of ALI had the largest AUC (0.875). Multivariate analysis did not identify any independent variable as associated with N+.

Statistical correlation between location and histological parameters in T1 colorectal cancer with lymph node metastasis.

| Parameters | pN0, n (%) | pN+, n (%) | p | AUC (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||||

| Colon | 19 (79) | 1 (20) | ||||

| Rectum | 5 (21) | 4 (80) | 0.040 | 0.796 (0.569–10) | 15.200 (1.375–167.98) | 0.009 |

| Grade | ||||||

| 1 | 22 (92) | 3 (60) | ||||

| 2 and 3 | 2 (8) | 2 (40) | 0.272 | 0.658 (0.361–0.956) | 7.333 (0.734–73.248) | 0.062 |

| ALI | ||||||

| No | 18 (75) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Yes | 6 (25) | 5 (100) | 0.0094 | 0.875 (0.748–1) | 1.833 (1.069–3.144) | 0.002 |

| TB | ||||||

| No | 16 (70) | 2 (40) | ||||

| Yes | 7 (30) | 3 (60) | 0.308 | 0.648 (0.371–0.924) | 3.429 (0.465–25.271) | 0.211 |

| PDCs | ||||||

| No | 19 (83) | 2 (40) | ||||

| Yes | 4 (17) | 3 (60) | 0.142 | 0.713 (0.438–0.988) | 7.125 (0.882–57.545) | 0.046 |

| Inflammation | ||||||

| No | 7 (29) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Yes | 17 (7) | 5 (100) | 0.302 | 0.645 (0.417–0.874) | 1.294 (1.032–1.623) | 0.166 |

| Pre-existing lymphadenoma | ||||||

| No | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Yes | 23 (96) | 5 (100) | 0.885 | 0.521 (0.245–0.796) | 1.217 (1.024–1.444) | 0.642 |

| Tumour border | ||||||

| POI | 9 (39) | 1 (20) | ||||

| INF | 14 (61) | 4 (80) | 0.509 | 0.596 (0.331–0.860) | 2.571 (0.246–26.851) | 0.418 |

| PNI | ||||||

| No | 23 (96) | 4 (80) | ||||

| Yes | 1 (4) | 1 (20) | 0.583 | 0.579 (0.279–0.879) | 5.750 (0.296–111.879) | 0.204 |

| Submucosal information | ||||||

| <1mm | 7 (30) | 1 (20) | ||||

| >1mm | 16 (70) | 4 (80) | 0.719 | 0.552 (0.279–0.825) | 1.750 (0.164–18.617) | 0.640 |

| Endoscopic margin | ||||||

| Free | 11 (85) | 2 (67) | ||||

| Affected | 2 (15) | 1 (33) | 0.638 | 0.589 (0.202–0.977) | 2.750 (0.162–46.792) | 0.473 |

The predictive value of each parameter is given as area under the curve (AUC) and odds ratio (OR).

Since the clinical follow-up of these patients was less than 3 years, no studies of correlation between histological factors, overall survival and disease-free interval were performed.

DiscussionSeveral histopathological factors that can potentially predict loco-regional lymph node metastases in minimally invasive CRC have been proposed over the years.1,16–22 Unfortunately, all studies analysing these histological parameters were based on cases in which the surgical specimens and, therefore, the lymph nodes, were available for evaluation. Evidently, in T1 cases that are not operated and which generally do not present adverse histological factors, lymph node stage cannot be definitively determined. These cases therefore represent a bias that will inevitably persist for a long time in this type of study.

Advances in endoscopic resection techniques and screening programmes for CRC have increased early detection rates.1–8 The low probability of metastasis of these neoplasms has led to local endoscopic or surgical resection becoming the treatment of choice for T1 CRCs, which, in turn, has improved patients’ quality of life, as it avoids further surgery and possibly even abdominoperineal amputation if the lesion is located in the lower third of the rectum.2–15 However, since endoscopic resection as a treatment is reserved for patients without metastatic spread,2–8 it is essential to continue seeking new information and factors indicative of lymph node spread in endoscopic resection samples, so as to be able to identify patients who could benefit from adjuvant treatment.

Current European recommendations for evaluating T1 CRC suggest that the histopathology report should include histological parameters such as the presence of ALI, status of the endoscopic resection margin, existence of poorly differentiated tumour areas and TB.27–29 Even if a pathologist reports the presence of adverse histological factors, it is recommendable that a multidisciplinary team composed of gastroenterologists, surgeons, oncologists and radiologists decides, on a case-by-case basis, whether additional surgical resection should be performed.1–9 This intervention would depend, among other factors, on the patient's age, location of the neoplasm (rectum or colon) and comorbidities.2–15

The evaluation criteria for histological parameters are not always consistent; moreover, not all have been validated in extensive series, and, when they have been, the criteria recommended in previous publications have not necessarily been applied.2–14 Japanese guidelines (JSCCR), in particular, recommend submucosal invasion depth as a crucial predictive parameter associated with the presence/absence of lymph node metastases.31 Ueno et al.,4 in a study of 3556 T1 CRCs, concluded that cases with submucosal invasion depth of less than 1mm were at very low risk of metastases. Despite the extensive series2–4 used as the basis for the Japanese guidelines, the depth criterion has not been fully implemented in Europe: apart from the time required to measure distances, the muscularis propria is not always included in endoscopic polypectomies of T1 CRCs, and the fact that it is very difficult to properly identify the muscle layer of the mucosa implies a certain degree of subjectivity.

ALI, logically, has been one of the criteria associated with N+ for many years. However, interobserver agreement in previous studies has not always been high, and it is sometimes very difficult to distinguish ALI from the retraction artefact seen in this type of neoplasm.1–13 Some studies do describe disagreements in the evaluation of ALI—with or without IHC—but there is adequate agreement in most.11–13 Observation by more than one pathologist (as in the present study) and agreement between pathologists in discordant cases probably provide adequate assessment of the presence of ALI.

The presence of TB is another recently described histological factor associated with N+, but its detection also presents difficulties. TB may go unnoticed by the pathologist if broad-spectrum cytokeratin ICH techniques are not used to detect isolated tumour cells, which evidently can be confused with non-tumour stromal cells that react to the inflammation associated with invasive neoplasms.1,10–22

Several recent studies with extensive series have evaluated PDCs, with findings demonstrating the significant association that exists between PDCs and the incidence of N+.2–8 This evaluation is evidently less subjective compared with assessment of other factors, as it involves tumour clusters or nests and, therefore, does not require the use of IHC markers for detection. The recently published study by Ueno et al.4 describes how PDCs represented, after ALI, the factor that most effectively predicted the risk of N+, regardless of the degree of submucosal invasion. These data are not completely inconsistent with European recommendations, which suggest further surgery to exclude lymph node metastases when a poorly differentiated component synonymous with the presence of PDCs is evident in an endoscopically resected pT1 ADC.28,29 The study by Ueno et al.4 also showed that evaluation of PDCs is more reproducible than evaluation of WHO histological grade and, furthermore, that interobserver agreement was better for PDC evaluation than for conventional tumour differentiation grade and presence of ALI.4 However, the international non-Japanese community of pathologists is reluctant to stop using the WHO-recommended histological grading system, despite the great interobserver variability. The reality is that no truly objective method exists for quantifying the percentage of gland formation.2–8

Although the univariate analysis performed for our series identified rectal location and the presence of ALI and PDCs as significantly associated with loco-regional nodal metastases, the multivariate analysis pinpointed no significant parameters for this group of pT1 tumours. The small number of pT1 tumours analyzed is, in this regard, evidently a main limitation of our study. Nevertheless, in our statistical analysis, two factors previously reported as highly predictive of metastasis2–8 (ALI and PDCs) were also significantly associated with loco-regional lymph node metastases—at least according to the univariate analysis. Moreover, the fact that the presence of ALI was the variable with the largest AUC (0.875) in our study corroborates results from several studies showing that ALI is highly predictive of lymph node metastasis.2–8

In Europe, Barresi et al.5–8 have published a series of studies of T1 CRCs. The two most recent studies7,8 confirmed that the mere presence of PDCs is highly predictive of N+, irrespective of the number of PDCs; these studies also showed that PDC evaluation to predict the metastatic potential of T1 CRCs is more reproducible than evaluation of submucosal invasion depth, ALI, TB and WHO histological grade. In Barresi et al.,7 as in the Japanese study (although with fewer cases), both invasion depth greater than 1mm and ALI were reported to be significantly associated with N+ (p<0.00019). Moreover, all T1 CRCs with lymph node metastases had a submucosal invasion depth of greater than 1mm in the primary tumour; however, the specificity of this factor in detecting N+ was lower than the specificity for PDCs (84.9%) and ALI (94.6%). Therefore, submucosal invasion greater than 1mm alone as a high-risk criterion might result in an increase in false positives and, consequently, in unnecessary additional surgeries.7 Interstingly, the same study demonstrated high specificity (88.2%) for the combination of submucosal invasion depth greater than 1mm and the presence of PDCs in identifying T1 N+ CRCs. This finding would suggest that PDC evaluation should be included in histopathology reporting, as the mere presence of PDCs has greater predictive value for N+ than grading based on counts.7

Given the importance of histological detection of PDCs as a predictor of loco-regional lymph node metastases in CRC, it would be interesting to investigate whether PDCs could be detected in endoscopic biopsies and whether they had the same predictive value for N+.

Barresi et al.8 recently published another study of the reproducibility, safety and predictive value of PDCs for 152 endoscopic biopsies, evaluated in order to predict loco-regional lymph node status and the pTNM stage for T1 CRCs. Using a novel histological grading system based on PDC counts—as previously described by the Japanese group4—they correlated the results for endoscopic biopsies (any T) and the surgical specimen, finding that cases with a high PDC grade were significantly associated with N+, advanced pTNM stage and histological findings for the surgical specimen indicative of aggressive neoplasm (TB, PNI, ALI and infiltrating tumour border). They concluded that this grading system could provide more information on the anatomical extent of the tumour than could be provided by WHO-classification grading according to the proportion of glandular component in preoperative endoscopic biopsies.8 One of the limitations of the Barresi et al.8 study referred to the location of the PDCs; these nests are generally located in the deep tumour invasion front, whereas most endoscopic biopsies provide samples from superficial areas of the tumour. Obviously, the above findings—evidently of great clinical importance for patient management and treatment—should be confirmed in further studies that would enable proper stratification, at the initial biopsy, of patients with a risk of nodal metastasis or at an advanced stage of their disease.

In our study, we did not correlate histological factors and distant spread, given the small number of patients who developed distant metastases. However, we did observe that not all primary tumours in these patients had adverse histological factors predictive of lymph node metastases (ALI, TB, PDCs). We also observed that only 3 of our patients had lymph node metastases in the surgical specimen. While countless studies have demonstrated the prognostic significance of molecular factors in advanced CRC, virtually none have shown the benefit of studying these factors in T1 CRCs as decisive in selecting suitable treatment for these patients. Some studies of more than 200 cases have encouragingly reported IHC CD10 expression to be significantly associated with lymph node metastases—for instance, the recent study by Nishida et al.22 The fact remains that some histologically adverse T1 CRCs do not progress to distant metastases; moreover, it is not known which factors truly influence, or are associated with, local or distant spread in the early stages of CRC.

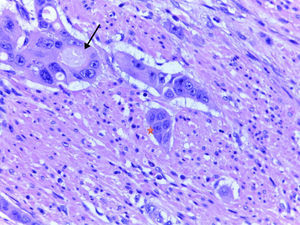

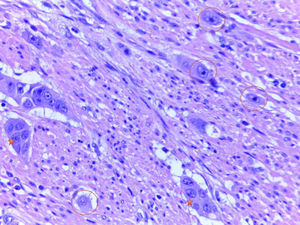

In conclusion, in view of the conclusively demonstrated association between adverse histological parameters—especially ALI, submucosal invasion depth greater than 1mm, TB and PDCs—and loco-regional lymph node metastases, evaluation of these parameters is highly recommended, especially for endoscopically resected T1 CRCs. Evaluating PDCs is particularly useful, considering that, of all of the parameters, it seems to be the most reproducible and to show the least interobserver variability. It would be useful, within a framework of European clinical trials or retrospective and prospective studies, to include pathologists from various institutions in the study of series with a large number of T1 CRCs, with a view to deciding whether the evaluation of these key histological factors could genuinely play a useful role in decision making for the treatment of early stage CRC (Figs. 1 and 2).

Isidro Machado and Miriam Valera-Alberni have contributed equally to the present study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

To the Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC) foundation for the grant awarded to Miriam Valera-Alberni.

Please cite this article as: Machado I, Valera-Alberni M, Martínez de Juan F, López-Guerrero JA, García Fadrique A, Cruz J, et al. Estudio de factores histológicos predictivos de metástasis ganglionar locorregional en adenocarcinoma colorrectal mínimamente invasivo pT1. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:1–8.