Gastrointestinal endoscopy (GE) encompasses a broad group of invasive diagnostic and therapeutic examinations that are very important for the study of the gastrointestinal tract. Despite being relatively safe and well-tolerated procedures, in elderly and/or frail people (E/F P) they are associated with an increased risk of adverse events, insufficient preparation and incomplete examinations.1

In Catalonia, the population has aged considerably over the last few decades. In 2020, the percentage of people over the age of 65 in the population of Catalonia overall increased to 19%.2 The population prevalence of frailty in people over 65 years of age approaches 10%, although there is no consensus in the data on prevalence rates of frailty in the population, probably because of differences in the conceptualisation and measurement of frailty.3

The prevalence of pathology - and therefore the performance of diagnostic tests - is usually higher in E/F P. Many times, however, the relevance of detecting a certain pathology is very low, since the patient will gain little or no benefit, either because there are no therapeutic options, or because treatment is not expected to improve quality of life or survival.4 One example would be colorectal polyps. The life expectancy of an E/F P is often much shorter than the time the polyp needs to progress to symptomatic cancer. However, perforation or bleeding after a polypectomy in an E/F P can be extremely serious.4 Therefore, the risk-benefit ratio of endoscopic treatments can be clearly negative in elderly or frail people.

Age itself is not a contraindication for the performance of any endoscopic procedure. In contrast, extreme frailty would contraindicate all endoscopic procedures, as well as any other aggressive procedure. However, moderate degrees of frailty do not represent an absolute contraindication in symptomatic patients, in whom GE may lead to a better quality of life. In these situations, the risk-benefit ratio of the test needs to be assessed on an individual basis.

It should also be remembered that before an invasive procedure such as GE the indication should always be based on shared decision-making. People have experiences, beliefs, and priorities that healthcare professionals do not know about which can influence their decisions. Shared decision-making allows healthcare professionals to take these into account and adapt diagnostic and therapeutic options to each individual.5

In conclusion, E/F P represent a heterogeneous population that requires a precise and individualised assessment of the indication for GE.

The objective of this position paper by the Societat Catalana de Digestologia (SCD), the Societat Catalana de Geriatria i Gerontologia (SCGiG) and the Societat Catalana de Medicina Familiar i Comunitària (CAMFiC) was to issue consensus recommendations, whenever possible based on evidence, risk assessment and the indications for GE in E/F P (Figs. 1 and 2).

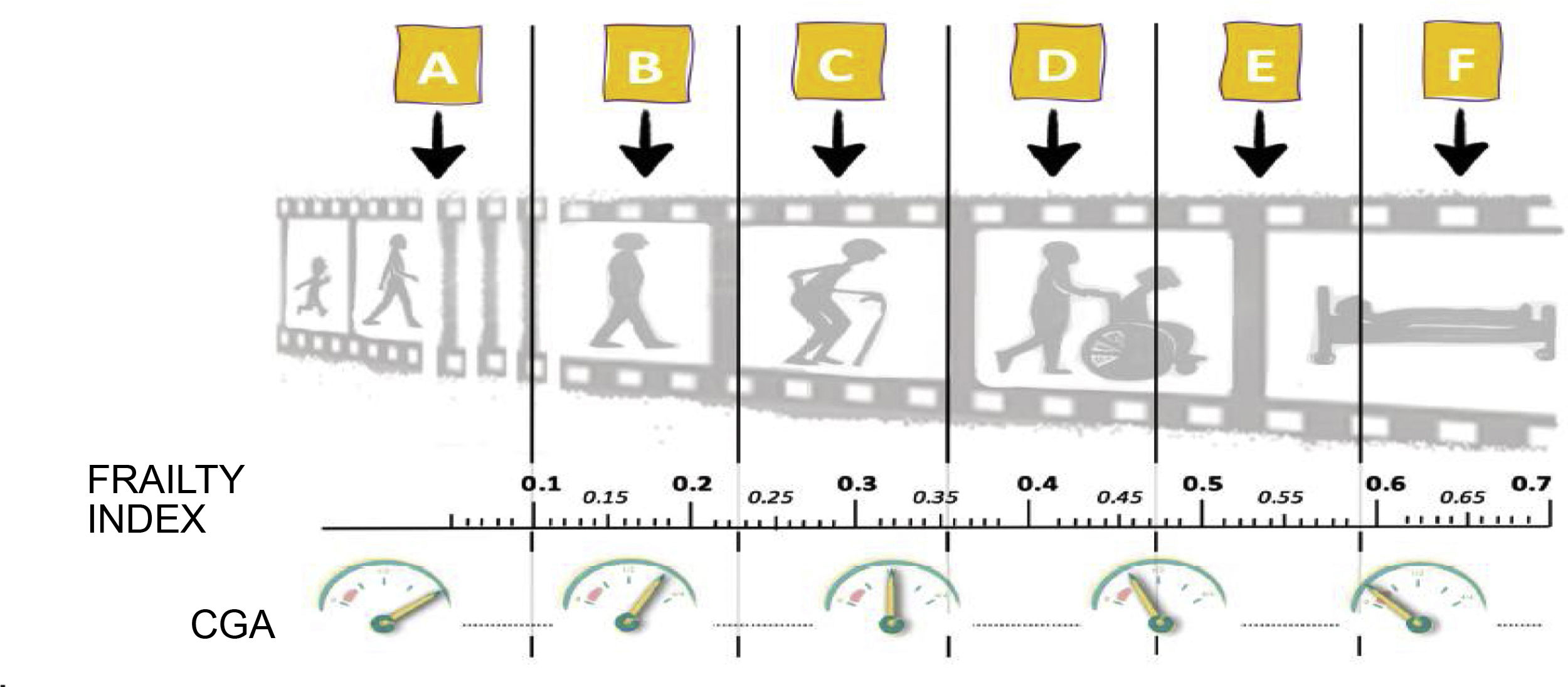

Situational diagnosis and degree of reserve regarding the person: How vulnerable is he or she?; Where is he or she in their life trajectory?: A, B, C, D, E or F?

Source: Conceptual foundations and model of care for frail people.4

CGA: Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment.

This consensus document was produced by a group of experts appointed by the SCD, the SCGiG and the CAMFiC in 2020 and 2021 (Fig. 3).

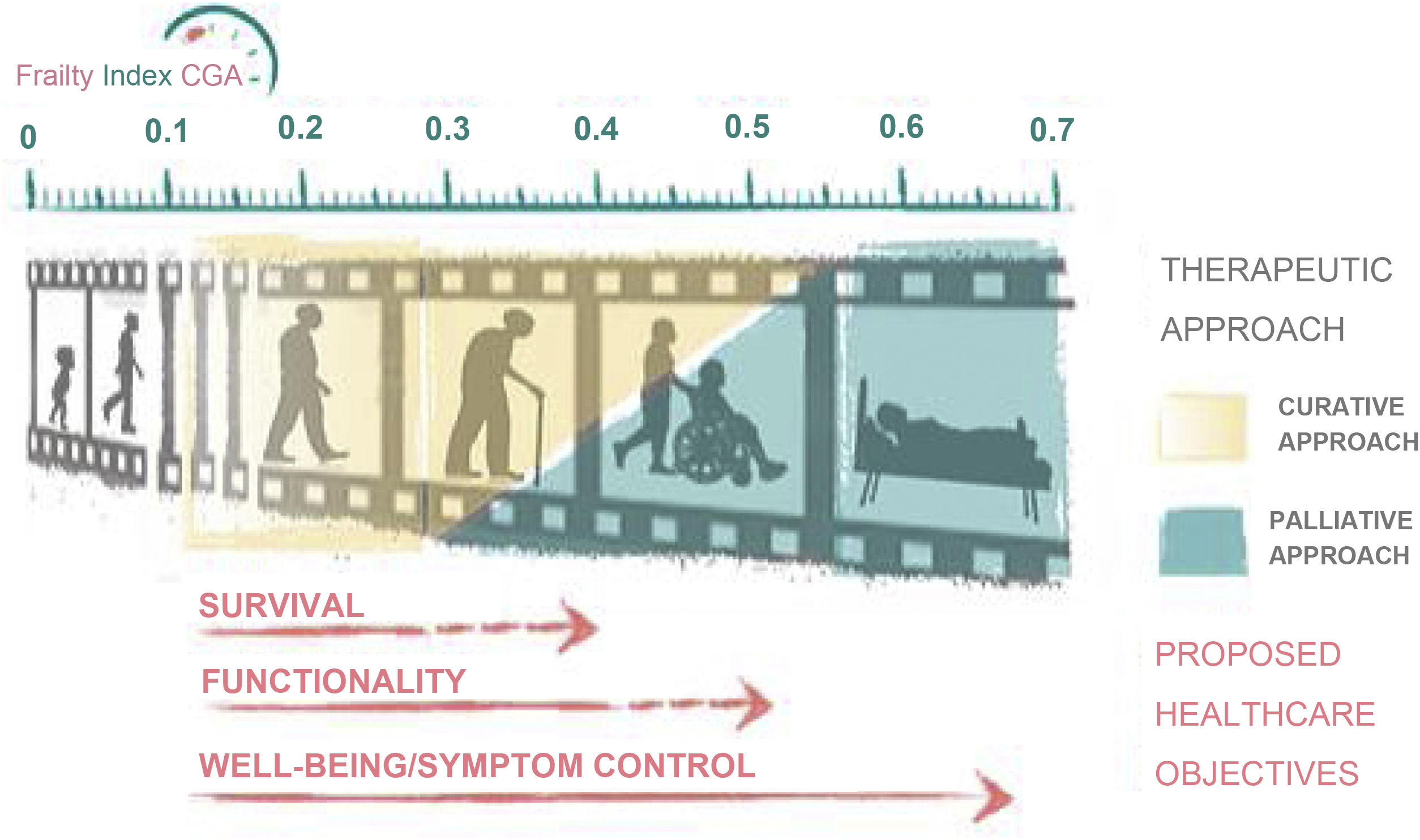

Frailty-CGA Index and therapeutic approach towards the patient. Based on certain values, functionality or well-being comes first and foremost, before survival.

Source: Conceptual foundations and model of care for frail people.4

Each section was drafted by a multidisciplinary team that included a geriatrician, a family doctor and a gastroenterologist. The experts conducted a non-systematic review of the evidence and used the references retrieved and their bibliographic bases to write each section. Finally, the sections were collated in a document that was reviewed individually by each of the experts. The controversial issues were discussed during several teleconferences in the course of 2021. With the results of the discussions, the final document was drafted and was revised again by each of the experts and by the boards of the respective societies. The final version of the document was approved at a final consensus meeting.

ResultsThe results were structured into four sections: a) an assessment of the risk-benefit ratio and indication for GE in E/F P, b) for whom a situational diagnosis should be made before a GE, c) who should make the situational diagnosis, and d) how the relationship between Primary Care, geriatrics and gastroenterology is articulated.

The general recommendations made by the consensus group are summarised in Table 1.

General recommendations made by the consensus group.

| Before any invasive intervention—and specifically a GE—in patients of advanced age and/or with frailty and/or with multiple pathologies, it is advisable to carry out a comprehensive geriatric assessment. |

| It is recommended that the CFS index be used as a rapid detection tool. A score of 1−4 does not limit explorations. With scores from 7 to 9, it is proposed that any invasive intervention be avoided. |

| In E/F P with CFS 5−6, a comprehensive geriatric assessment is warranted. If this is not possible, an assessment with the Frailty-CGA Index can be made, to decide on the appropriateness of GE, inform the patient and/or family of the prognosis and establish a consensual care plan. |

| Assessment of frailty in the first instance is the responsibility of Primary Care teams. |

CFS: Clinical Frailty Scale; CGA: Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment; E/F P: elderly and/or frail people; GE: Gastrointestinal endoscopy; PC: Primary Care.

The individualised adaptation of the intensity of treatment or of the diagnostic tests should always be carried out according to the risk-benefit balance.

In elderly patients, decision-making can be facilitated by establishing a situational diagnosis.6

The concept of a situational diagnosis refers to the outcome of the multi-dimensional assessment process and patient needs that allows practitioners to determine the degree of reserve or frailty of the person cared for (How vulnerable is he/she? Where is he/she? At what point in his/her life span?) and identify the losses or dimensions affected and needs to be met.6

Ideally, the situational diagnosis is conducted with a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) This requires time and an interdisciplinary team, so as an alternative it is proposed that rapid multidimensional/geriatric assessment tools be considered. The two tools recommended in this document are described below:

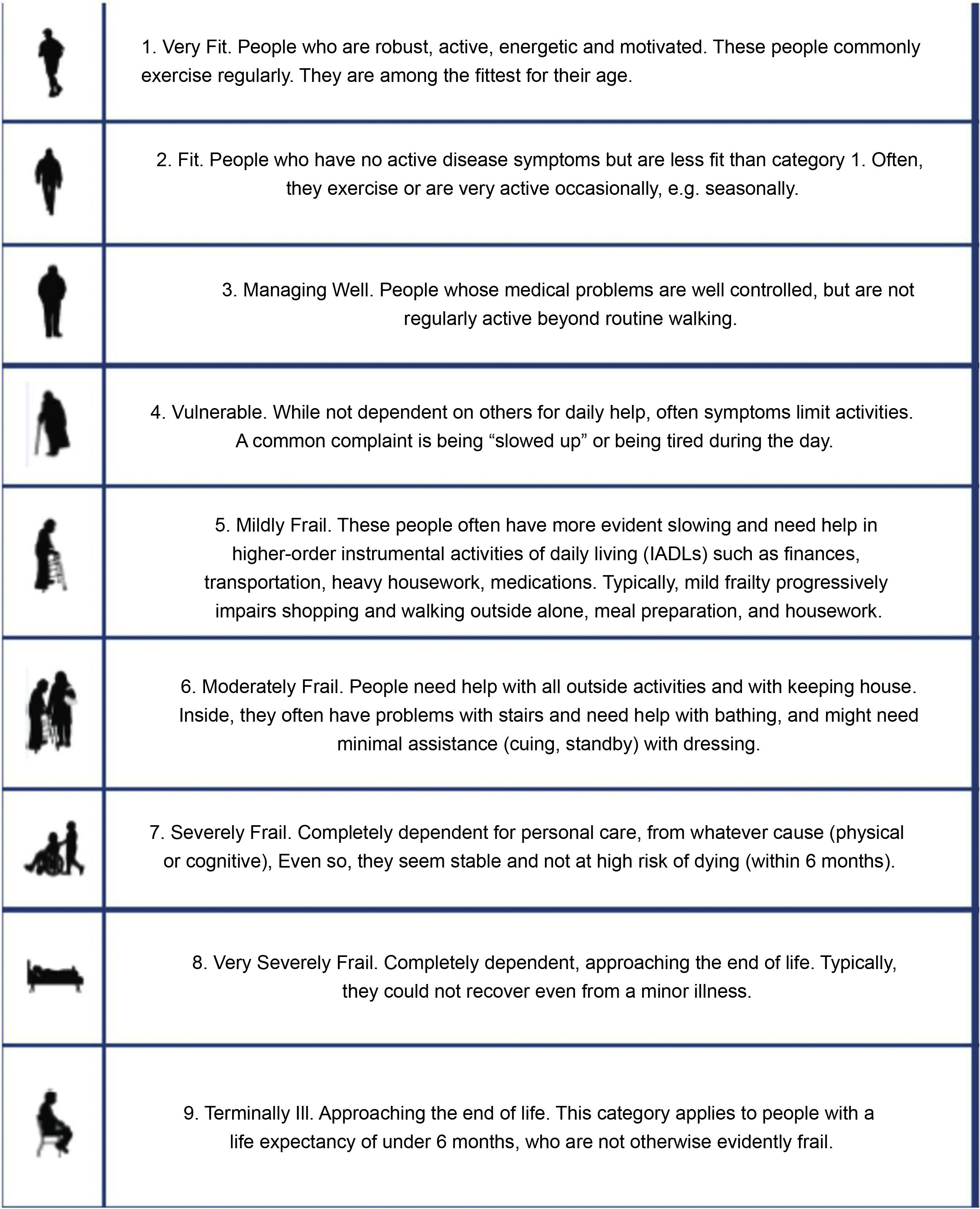

Clinical Frailty Scale (Annex 1)The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is a very straightforward way to determine a person's degree of frailty, ranging from 1 to 9, and is based primarily on clinical trials.7 The CFS has been validated as a predictor of adverse effects in older people.8,9 This qualitative assessment of frailty can help us make decisions about health goals. For example, patients with frailty levels 7-8-9 (living with severe frailty, living with very severe frailty and/or terminally ill) are only candidates for non-invasive approaches and would not therefore be candidates for GE.

The CFS is also available as an app, which can be downloaded from https://www.acutefrailtynetwork.org.uk/Clinical-Frailty-Scale/Clinical-Frailty-Scale-App.10

Dementia does not limit the use of the scale. People with dementia follow a similar pattern to that of the CFS: mild, moderate, and severe dementia would correspond to CFS levels 5, 6, and 7, respectively. If the degree of dementia is not known, the standard CFS classification would need to be followed. Recommendations for the correct use of the CFS are detailed in Appendix B Annex 1.11

The Frailty-CGA index (Annex 2)(Appendix B Annex 2) The Frailty-CGA (Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment) Index [Índice Frágil-VIG] is a frailty index based on the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. It has been shown to be simple (with respect to content), fast (it can be administered in 5−10 min), accurate (it facilitates situational diagnosis through a continuous variable) and highly predictive (it has a high correlation with mortality).

The Frailty-CGA Index facilitates the adaptation of therapeutic intensity (providing actions according to the clinical situation and the patients' desires), advanced planning and optimisation of resource use based on healthcare objectives agreed on by patients, family members and professionals.12

The Frailty-CGA Index can be determined with the help of an online calculator. The Frailty-CGA Index calculator and a short instruction manual can be downloaded from: https://www.c3rg.com/index-fragil-vig.13

Who should have a situational diagnosis before a gastrointestinal endoscopy?E/F P benefit from an individualised, person-centred approach. This approach is useful for people with complex healthcare needs or a complex chronic disease (complex chronic patient [CCP]) such as those with palliative needs or advanced chronicity [MACA modelo de atención a la cronicidad avanzada (advanced chronicity model of healthcare)] (Appendix B Annex 3 and 4).6,14,15

A comprehensive geriatric assessment should be conducted for anyone over 80 years of age and for all patients with multiple pathologies, in this case regardless of age. If no geriatric assessment has been made, it should be conducted prior to any invasive intervention, such as endoscopic procedures.

Who should make the situational diagnosis?In clinically complex situations, decision-making is an interdisciplinary collaborative process that sometimes requires collaboration between different care tiers. That said, assessment of the degree of frailty and the situational diagnosis will normally be performed by the patient's usual reference teams, such as Primary Care physicians (PCPs) who, because of their proximity and continuity of care, understand the patient's overall situation and can determine the degree of frailty more easily.

This pre-GE assessment should be recorded in the medical record. If it is not there, a geriatric assessment of the patient by the PCP teams prior to requesting GE is recommended. An initial assessment by Primary Care is recommended using CFS as screening and the Frailty-CGA Index if there is any doubt. It is also advisable to request a specialised geriatric assessment in the most complex cases.

Geriatric teams specialise in assessments of the highest clinical complexity and should act if necessary. However, other hospital teams can make a quality situational diagnosis. The ultimate goal will be that all teams that normally care for the patient always adopt an overall perspective, not one exclusively focused on a specific disease.

If the geriatric assessment is not available in the shared medical record (SMR), the gastroenterologist evaluating the GE request may perform an interim evaluation based on SMR data. Since the gastroenterologist's assessment will be based on indirect data and without knowing the patient personally, it is considered to be less accurate. Therefore, it is proposed only if there is no recent Primary Care or geriatrics assessment or if there is a very obvious discrepancy between the available geriatric assessment and SMR data. If in doubt, the assessment by the gastroenterologist should be confirmed or validated together with the appropriate Primary Care or geriatric teams before a final decision is made.

Indications for GE according to degree of frailtyIndications in advanced frailty (Frailty-CGA Index > 0.5 or CFS ≥ 7)As mentioned above, in patients with advanced frailty, diagnostic-therapeutic objectives are usually based on guaranteeing well-being and symptomatic control. In general, invasive measures, including endoscopic examinations, do not play a role, due to patients' shorter life expectancy and the high risk of complications.

Indications in mild-moderate frailty (Frailty-CGA Index 0.2–0.5 or CFS 5–6)In patients with mild or moderate frailty, the diagnostic-therapeutic objectives are intended to obtain a clinical benefit to promote and maintain autonomy and quality of life, but not survival. Therefore, the indication for the test must be assessed and a decision taken as to whether the outcome could lead to measures that would improve the patient's functional status or quality of life.

No frailty or pre-frailty (Frailty-CGA Index < 0.2 or CFS 1–4)In patients with no frailty or pre-frailty Frailty-CGA Index < 0.2 or CFS 1–4, the diagnostic-therapeutic objectives are similar to those of the general population, and preventive measures to improve survival should also be considered appropriate.

What is the relationship between primary care, geriatrics and gastroenterology?There are currently different systems of relationship between Primary Care physicians (PCPs), geriatricians and gastroenterologists. The idiosyncrasy of organisations and the resources available define the systems established in each case. Telemedicine is increasingly relevant and enabling, which should have an impact on improved user care.

Therefore, in this guide, we do not intend to make concrete recommendations, knowing that they will be obsolete and that they are subject to the specificities of each territory. We would like to emphasise the importance of establishing and strengthening connection systems that facilitate the interrelationship in a streamlined and two-way manner. We will only suggest a few tools that may be useful. Thus, certain existing communication experiences that have proven useful are:

- -

Development of protocols shared with multidisciplinary teams in a given territory. These protocols can be developed nationally or locally, and general recommendations can also be applied locally.

- -

Virtual interconsultations between Primary Care and Gastroenterology or Geriatrics.

- -

Use of specific social networking or instant messaging groups (XatSalut)16 preserving patient confidentiality.

- -

Periodic virtual or face-to-face meetings between the Primary Care, Gastroenterology, and Geriatrics medical teams and meetings to review complex clinical cases. This makes a joint agreement on the management of clinical cases possible. In especially complex cases that require it, meetings of more than one speciality may be held.

- -

Creation of the figure of the primary care referee. A primary care physician with a special interest in a specific pathology, in this case gastroenterology and geriatrics. This referee would be responsible for training activities and communication with hospital specialists. In addition, Primary Care, Gastroenterology or Geriatrics nursing teams would play a very important role in the comprehensive geriatric assessment and use of the Frailty-CGA Index.

- -

Creation of a referee-specialist for primary care: a hospital specialist who supports one or more primary care centres. This person would coordinate activity with Primary Care teams in their reference area for non-patient consultations, case discussion meetings, and teaching activities.

- -

In the case of elderly patients, geriatric services can offer support both through the resolution of specific inter-consultations and through the direct management of complex patients and/or patients with advanced disabilities.