Medicine has changed enormously over last century. That is a given. It has changed not only in terms of expertise, technological and diagnostic developments and therapeutic advances, but also in terms of objectives. Not so long ago, the aim of medicine was to try and save the lives of patients with very severe illnesses, or to relieve extreme suffering. Today, however, patients not only want to live, or live pain-free, they also want to live better. This has led to a special focus on a new term: “health-related quality of life”.1

Health-related quality of life is, without a doubt, a fundamental measure of the impact of healthcare. There is a practically unanimous opinion among healthcare professionals that traditional outcome variables (mortality/morbidity) are not suitable for giving an adequate view of the effect of healthcare and medical intervention. Therefore, medical objectives should be aimed not only at treating the disease itself but more importantly at improving quality of life.

Anaemia: much more common than we thinkAnaemia is a very common disorder worldwide, although there are major variations in prevalence depending on the socio-economic status of each country. Likewise, while it is very common and usually associated with nutritional deficiencies in underdeveloped countries and among the lower social strata of developed countries, it is much less common among the rest of the population.

Furthermore, iron deficiency anaemia is highly prevalent and affects individuals of both genders and all ages. It occurs when iron absorption does not meet demands, due to either a lack of availability, increased requirements or increased losses.2 It is generally estimated that iron deficiency may be present in 6% of adults, affecting up to 10–15% of women. Moreover, the prevalence of anaemia is around 1.5% in men aged 17–49 and up to 26% in men over 84; it is 12% in women aged 17–49, 7% in women aged 50–64 and 20% in women over 84.3

The most common causes of iron deficiency anaemia are: malnutrition in children, menstrual blood loss or lactation in women of child-bearing age and chronic bleeding, especially as a result of gastrointestinal lesions in adult men and individuals over the age of 65.4 Anaemia in the presence of gastrointestinal disorders is undoubtedly very common. It is estimated that approximately two-thirds of patients with iron deficiency anaemia have gastrointestinal lesions.5

Digestive diseases and anaemia: a common duoAbsorption, loss or regulation of iron metabolism can be affected in many digestive diseases.6 It is estimated that 4% of appointments with or referrals to gastroenterologists are due to iron deficiency anaemia.7

Chronic gastrointestinal bleeding (GI bleed) is the primary cause of iron deficiency anaemia in adult men and post-menopausal women.8 Its causes are varied and a thorough study of the entire gastrointestinal tract is required to detect such bleeding, although conventional investigations do not effectively manage to identify it in 5% of cases (recurrent obscure GI bleed).9 The most common causes are the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antiplatelet drugs, polyps or colorectal cancer, stomach cancer, angiodysplasia and inflammatory bowel diseases.

Acute GI bleed is also a very common complication and a cause for emergency appointments and hospitalisation in a high number of cases. Varying levels of blood loss causes decreased blood volume (hypovolaemia) and subsequent development of post-haemorrhagic iron deficiency anaemia. There is limited information on the number of patients developing iron deficiency anaemia after an episode of acute GI bleed. In one study conducted in Spain, it was discovered that, 30 days after an episode of acute GI bleed, 62% of patients had iron deficiency anaemia.10

Iron deficiency anaemia is the most common systemic complication in inflammatory bowel diseases as a consequence of bleeding, inflammation, malabsorption or dietary restrictions.11 The most common cause is blood loss and resulting iron deficiency, but vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency, malnutrition, malabsorption, administration of certain drugs or inflammation can also give rise to anaemia.12

In coeliac disease, anaemia is the most common extraintestinal complication. It occurs due to malabsorption of iron and other micronutrients, although anaemia of chronic disease has also been described as a consequence of inflammation and the action of pro-inflammatory cytokines.13 It is estimated that 5–6% of patients diagnosed with iron deficiency anaemia have coeliac disease.14 In one study conducted in Spain, the prevalence of coeliac disease in patients with iron deficiency anaemia and no other manifestations was 3.3%.15

In stomach cancer, anaemia is a common finding at the time of diagnosis. Whether anaemia is due to iron deficiency or secondary to a chronic disease, it is one of the most common manifestations and results in elevated morbidity and mortality rates and poor quality of life.

The gastroenterologist and anaemia: we sometimes lose our wayCompared with other complications, anaemia has historically been overlooked by gastroenterologists.16 Also, the lack of suitable treatment strategies has been associated with increased morbidity and poor quality of life in anaemia patients.17 Nevertheless, over the last decade, digestive disease-associated anaemia has become more important based on scientific evidence and improved knowledge of the mechanisms involved in this disease, and also the discovery of new therapies.

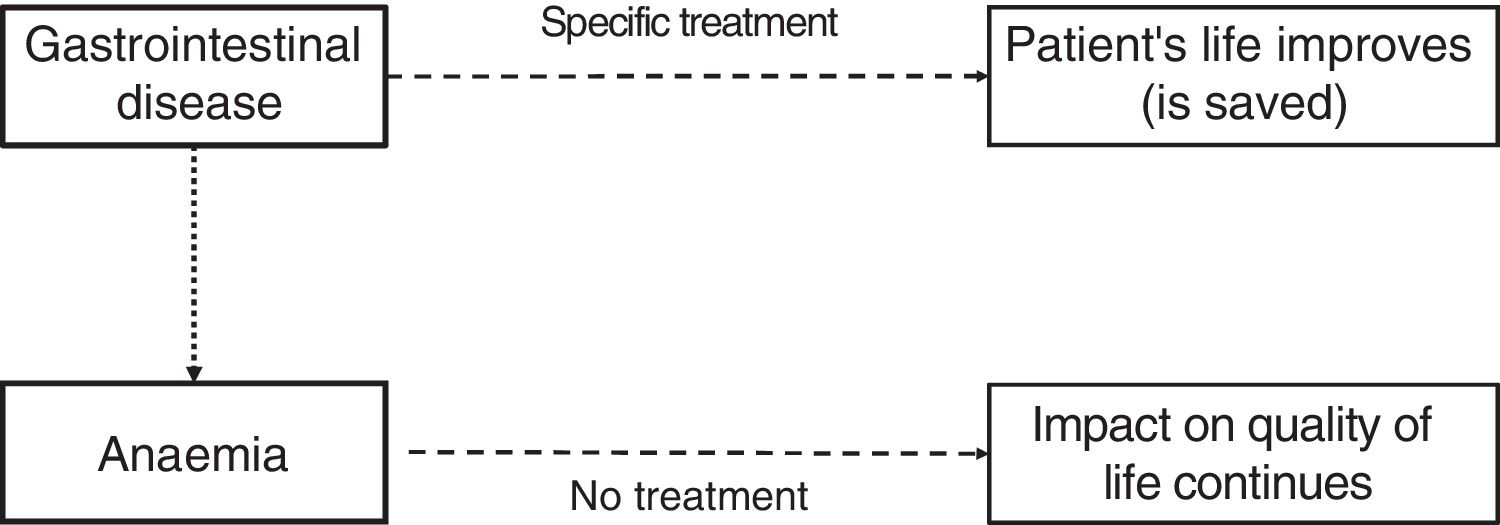

However, gastroenterologists (who perhaps focus on treating the original disease) forget about the study and treatment of anaemia and iron deficiency (Fig. 1). Therefore, one study conducted in Spain to analyse the prevalence of anaemia and iron deficiency in patients hospitalised with gastrointestinal diseases observed that the global prevalence of anaemia upon admission and discharge was as high as 60%. Furthermore, 3–6 months after admission, the prevalence of anaemia had only fallen by one half. It must also be mentioned that the iron levels of more than two-thirds of patients admitted to hospital were not tested upon discharge and only half of the patients admitted received treatment, even though a considerable number of cases had severe anaemia. In fact, upon discharge, less than half of the patients, including those with mild/moderate and severe anaemia, received treatment for their anaemia.18 These data are, of course, unacceptable given that anaemia and iron deficiency have a notable impact on quality of life, affecting both physical and emotional aspects.

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding and anaemia: an example of forgetfulness (bleeding is controlled but anaemia is forgotten)GI bleeds tend to be managed fairly well. The same, however, cannot be said for anaemia and iron deficiency often associated with GI bleeds. There are many erroneous beliefs concerning the management of anaemia in patients with GI bleeds, relating to both its prevalence and impact and to its diagnosis and treatment. A review has been published in this issue of Gastroenterology and Hepatology highlighting some of the misconceptions frequently held by doctors in relation to anaemia secondary to GI bleeding.19 The main conclusions of this article are: (1) iron deficiency anaemia in patients with GI bleeding is often moderate or severe; (2) anaemia and iron deficiency in patients with GI bleeding have a large impact on quality of life; (3) the doctor is not sufficiently aware to detect and treat anaemia during admission and discharge in patients with GI bleeding; (4) when treating iron deficiency anaemia in patients with GI bleeding, the aim is to achieve completely normal haemoglobin levels; (5) administration of intravenous iron should not be restricted to patients with GI bleeding who have severe anaemia (haemoglobin<10g/dL); (6) the necessary dose of intravenous iron should be personalised, but 1000mg is often given; (7) the efficacy and safety of intravenous iron is clearly established; (8) treatment with intravenous iron may be critical in patients with iron deficiency anaemia seen in the emergency department for self-limiting GI bleeds and who are discharged early without needing admission; and (9) the gastroenterologist's role not only involves controlling the GI bleed but also treating the associated anaemia and iron deficiency.

SummaryPatients not only want to live, or live pain-free, they also want to live better. This has led to a special focus on health-related quality of life. It is possible to live with anaemia, but quality of life is worse. The presence of anaemia is very common in digestive diseases. However, compared with other complications, anaemia has historically been overlooked by gastroenterologists. Doctors, perhaps focusing on treating the original disease, often forget about the study and treatment of anaemia and iron deficiency.

Correct management of patients with gastrointestinal diseases includes identifying anaemia and/or iron deficiency, during admission, upon discharge and during follow-up, and initiating the most appropriate treatment for anaemia based on the underlying digestive disease. In some cases, treatment may be given orally, but if tolerance is low or a large quantity of iron is required or a rapid response is required, intravenous treatment may be necessary.20

Please cite this article as: Mearin F. Vivir sin anemia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:223–225.