Although low-grade dysplasia (LGD) in Barrett's esophagus (BE) is a histopathological diagnosis based on different histological abnormalities, it is still problematic for different reasons. Patients without confirmed diagnosis of LGD undergo unnecessary and intensified follow-up where the risk of progression is low in the majority of cases. In contrast, the presence of confirmed LGD indicates a high risk of progression. In this article we try to address these reasons focusing on re-confirmation of LGD diagnosis, interobserver agreement, and persistent confirmed LGD. The progression risk of LGD to high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma will also be reviewed.

Aunque la displasia de bajo grado (DBG) en el esófago de Barrett (EB) es un diagnóstico histopatológico basado en diferentes anomalías histológicas, este no deja de ser problemático por diferentes razones. Los pacientes sin diagnóstico confirmado de DBG se someten a un seguimiento innecesario e intensificado donde el riesgo de progresión es bajo en la mayoría de los casos. Por el contrario, la presencia de DBG confirmada indica un alto riesgo de progresión. En este artículo tratamos de abordar estas razones centrándonos en la reconfirmación del diagnóstico de la DBG, la concordancia entre observadores y la DBG confirmada y persistente. También se revisará el riesgo de progresión de la DBG a displasia de alto grado y adenocarcinoma esofágico.

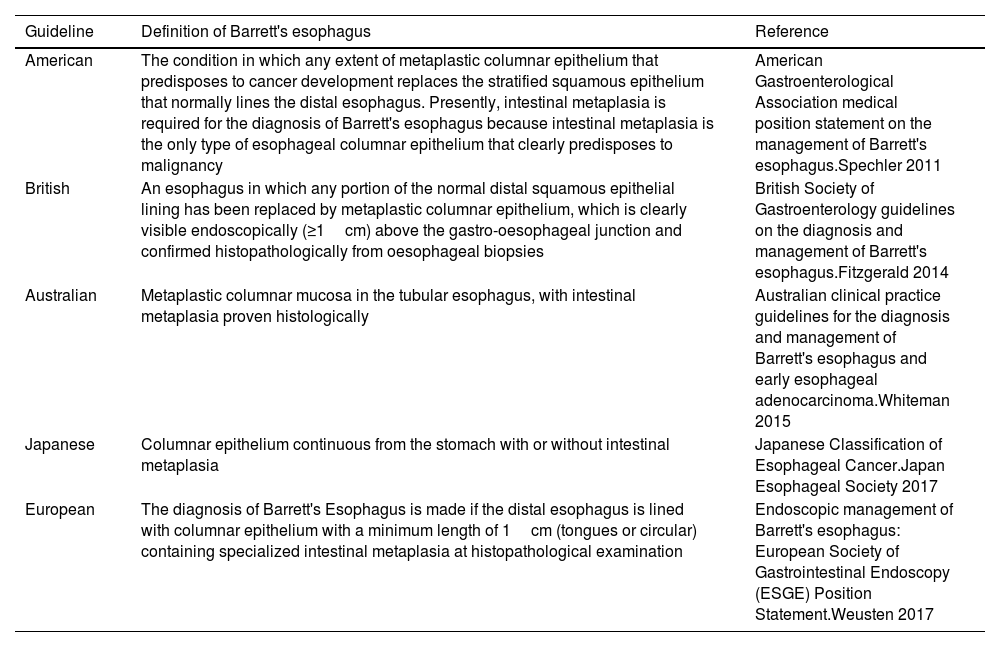

Barrett's esophagus (BE) is a premalignant condition to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), that develops in a minority of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), it is a metaplastic change in which the normal squamous epithelium in the tubular esophagus is replaced by the presence of columnar epithelium above the gastroesophageal junction. However, the global definition of BE is controversial; For the European, American and Australian Guidelines the presence of goblet cells within the metaplastic columnar epithelium of the esophagus (MCEE) is required for the diagnosis of BE, this kind of MCEE is named intestinal metaplasia (IM).1–5 In contrast, in the Japanese and British guidelines the definition of Barrett's mucosa does not consider goblet cells for the diagnosis of BE2,6 (Table 1).

Definition of Barrett's esophagus.

| Guideline | Definition of Barrett's esophagus | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| American | The condition in which any extent of metaplastic columnar epithelium that predisposes to cancer development replaces the stratified squamous epithelium that normally lines the distal esophagus. Presently, intestinal metaplasia is required for the diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus because intestinal metaplasia is the only type of esophageal columnar epithelium that clearly predisposes to malignancy | American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett's esophagus.Spechler 2011 |

| British | An esophagus in which any portion of the normal distal squamous epithelial lining has been replaced by metaplastic columnar epithelium, which is clearly visible endoscopically (≥1cm) above the gastro-oesophageal junction and confirmed histopathologically from oesophageal biopsies | British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett's esophagus.Fitzgerald 2014 |

| Australian | Metaplastic columnar mucosa in the tubular esophagus, with intestinal metaplasia proven histologically | Australian clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett's esophagus and early esophageal adenocarcinoma.Whiteman 2015 |

| Japanese | Columnar epithelium continuous from the stomach with or without intestinal metaplasia | Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer.Japan Esophageal Society 2017 |

| European | The diagnosis of Barrett's Esophagus is made if the distal esophagus is lined with columnar epithelium with a minimum length of 1cm (tongues or circular) containing specialized intestinal metaplasia at histopathological examination | Endoscopic management of Barrett's esophagus: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement.Weusten 2017 |

Of all types of MCEE, IM is the most biologically unstable epithelium with the greatest risk of neoplastic progression,2,7,8 nevertheless, about 25% of patients do not reveal goblet cells in their esophageal,9 there are growing evidence suggests that a columnar epithelium without goblet cells in patients with BE has also a premalignant nature.10 Results from other studies also revealed that EAC do not exclusively develop from IM and can be developed from gastric cardiac-type mucosa.11

BE could progress to low-grade dysplasia (LGD), high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and EAC, where the presence and grade of dysplasia are key predictors of progression risk to EAC7,8 although most patients harbor nondysplastic BE (NDBE).

In cases where the surface epithelium is denuded, uninvolved, or unable to be evaluated, the grading is changed to indefinite for dysplasia (IFD); this diagnosis is used for biopsies that are neither unequivocally dysplastic nor negative for dysplasia (NFD). The diagnosis of IFD should be considered a temporary diagnosis only and should prompt further close follow-up with adequate biopsy sampling.12,13

LGD diagnosis is based upon a variety of histologic abnormalities,14 its endoscopic recognition is difficult on the conventional and magnified endoscopic imaging,15 for this reason and for its patchy distribution,16 after a careful endoscopic evaluation of the BE segment and target biopsies from visible lesions, multiple random biopsies taken according to the Seattle protocol (systematic sampling from four quadrants at the gastroesophageal junction and at every 1–2-cm intervals along the entire length of the Barrett segment) is still necessary for microscopic diagnosis. Along with this systematic pattern of biopsy taking, it has been demonstrated that greater biopsy numbers may enhance pathologist's diagnosis.8

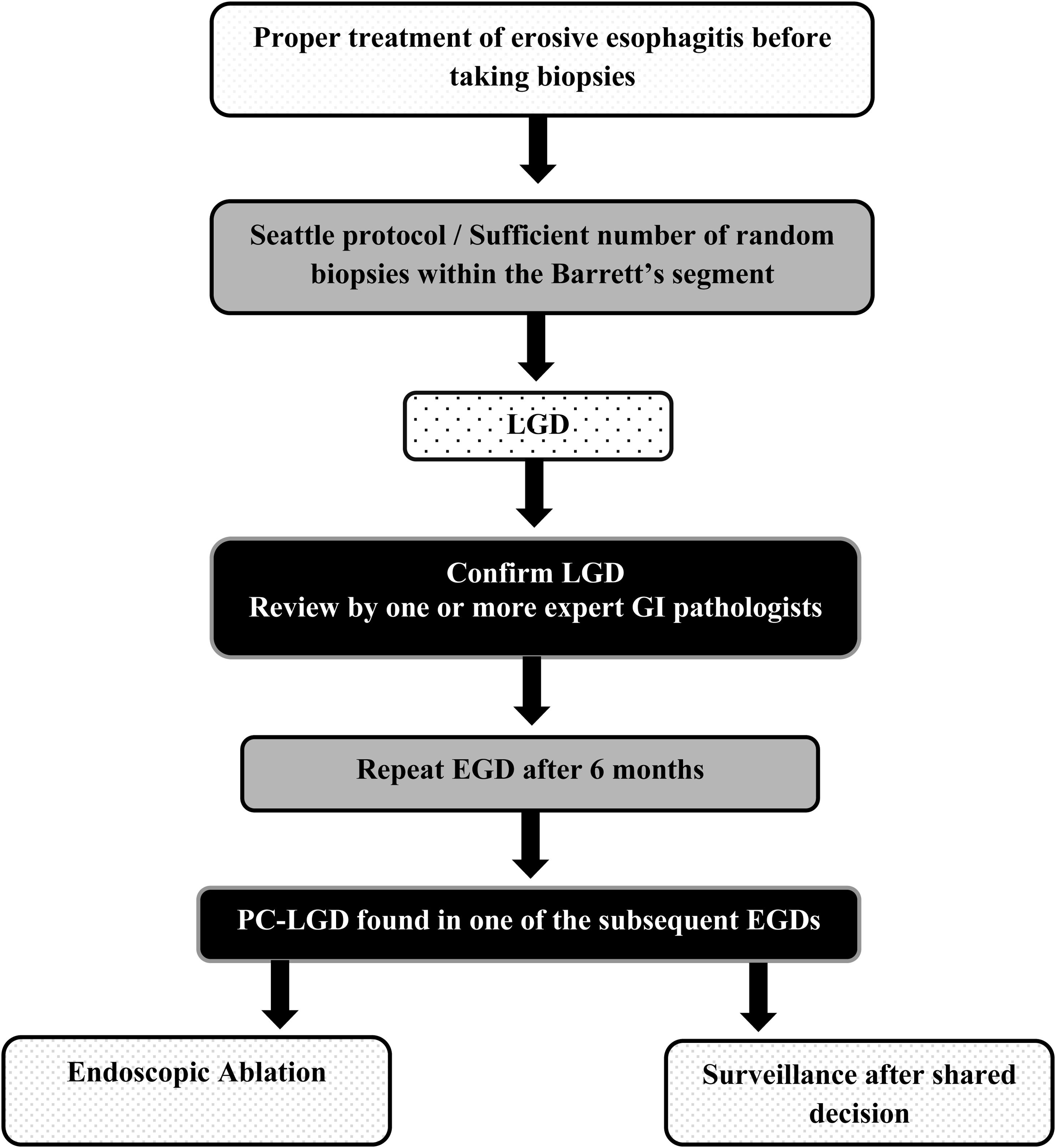

Due to the possibility of overdiagnosis of LGD related to inflammation, biopsies should not be performed in the presence of active inflammation, erosive esophagitis; in this case, biopsies should be taken after an adequate treatment with high-dose twice daily dosing of proton pump inhibitor therapy for 8 to 12 weeks to ensure healing and exclude overdiagnosis1,2,8 (Fig. 1).

When diagnosed, LGD should be confirmed by a second expert GI pathologist,17,18 if LGD is not confirmed at 6-month endoscopy, an appropriate surveillance should be offered according to guidelines, while for persistent confirmed LGD ((PC-LGD) LGD detected at the first and follow-up endoscopy) an endoscopic treatment should be carried out.19,20

In general, patients with HGD and intramucosal adenocarcinoma (IMAC) are treated endoscopically, the management strategy for LGD, however, includes endoscopic surveillance or therapy.

This narrative study reviews the reason of difficulties in making a diagnosis of LGD, where re-confirmation of LGD, interobserver agreement and PC-LGD concept will be emphasized. Also, this review shows that confirmation of LGD by expert GI pathologists is associate with a substantially higher risk of progression.

Epidemiological aspectsThe prevalence of NDBE in GERD patients is highly variable ranges widely from 0.4% to more than 20%.21 In patients with NDBE, LGD and HGD, the risk of neoplastic progression is around 0.2–0.5%, 0.7% and 7% per year respectively.22,23

A meta-analysis based on 47 studies showed that the incidence of EAC in BE was 6.1 per 1000 person-years24; in patients with HGD the incidence is estimated in 6 per 100 patient-years25 and 0.54% per year for LGD.26

The incidence of EAC in patients with BE increases progressively with age specially in patients over 70 years of age.27,28 There is a six to ten-fold increase of the risk of progression to EAC in male gender compared to women and four-fold increase in white males compared to black males.29,30 Tobacco use, obesity and first-degree family history of BE or EAC are another risk factors of neoplastic progression.30,31

Re-confirmation of LGD by expert GI pathologistsDysplasia diagnosis is based on cytologic and architectural features. Fortunately, pathologists have a good track record at detecting HGD and IMAC, lesions that usually need endoscopic or surgical resection; nevertheless, the histologic diagnosis of LGD is generally problematic, largely because it is unreliable when the diagnosis is made by a single pathologist and on the other hand there is a variation in diagnosis among pathologists.32

A retrospective study showed that general pathologists with little annual experience evaluating BE biopsy specimens did not successfully risk stratify patients with BE when compared with subspecialized GI pathologists.33 Curvers et al. reviewed, by an expert panel of pathologists, the original histological diagnosis of 147 patients diagnosed with LGD in 6 community hospitals in The Netherlands, and they found that 85% of them were downstaged to IFD or to NFD. LGD was confirmed in only 15% in whom the incidence rate of HGD or EAC was 13.4% per patient per year, compared with just 0.49% in patients downstaged to NFD with a mean follow-up of 51.1 months; the interobserver agreement (IOA) among the expert pathologists was moderate (kappa=0.50). The authors concluded that LGD in BE is an overdiagnosed and yet underestimated entity in general practice.34 Similar results were found in another retrospective cohort study from the same group of experts, where a histological review by an expert pathology panel of 293 LGD diagnosed between 2000 and 2011 revealed that 73% was downstaged to IFD or NFD, while in only 27% of them, the initial LGD diagnosis was confirmed; for confirmed LGD and for patients downstaged to IFD and NFD, the risk of HGD/EAC progression was 9.1%, 0.9% and 0.6% per patient-year, respectively with a median follow-up of 39months.35 Another cohort from the UK showed that the progression to HGD/EAC in patients with validated LGD was almost identical to those results.36

According to these results, the majority of patients with LGD will be downstaged after expert review and in fact they will be at low progression risk, however patients with confirmed LGD have a markedly increased risk of malignant progression, which should be actively sought by performing a systematic pattern of biopsy taking and obtaining enough biopsies to be reviewed and confirmed by expert pathologists.

Inter-observer agreementAs we mentioned above, several studies have shown that when LGD is diagnosed by general pathologists the progression rate is low, but when these cases were reviewed by GI pathologists, many of them were downgraded to no dysplasia; nevertheless, there is a significant interobserver variation in diagnosis, even among expert GI pathologists.37

More than 30 years ago, Reid et al. manifested that expert GI pathologists can diagnose HGD and intramucosal EAC with a high degree of IOA, but the potential value of biopsies surveillance of patients with BE for LGD was diminished by a lack of agreement on the diagnostic criteria for dysplasia.38 Nevertheless, a rigorous assessment of IOA among 12 GI pathologists revealed that after a consensus meeting to establish the histologic criteria for grading dysplasia in BE, IOA was substantial for HGD/carcinoma (kappa=0.65) but fair for LGD (kappa=0.32) and slight for IFD (kappa=0.15). Both intraobserver and interobserver variation improved overall after the application of a modified grading system developed at the consensus meeting but not in separation of LGD and IFD.39

Of 12 histologic criteria associated with LGD, Ten Kate et al. identified and validated that a panel of 4 histologic criteria (loss of maturation, mucin depletion, nuclear enlargement, and increase of mitosis) achieved a moderate or good IOA amongst 4 GI pathologists and may be valuable to improve prediction of neoplastic progression in patients with LGD diagnosis. These 4 criteria may differentiate high-risk and low-risk group of LGD patients (P<0.001) which improve their progression prediction as well as clinical decision making; when ≥2 criteria were present, a significantly higher progression rate to HGD or EAC was observed.40

Skacel et al. randomized and blindly reviewed, by three GI pathologists, biopsy specimens from 43 patients diagnosed and coded as LGD. Individual GI pathologists agreed with the original diagnosis of LGD in 70%, 56%, and 16% of cases and their diagnosis did not correlate with progression. However, when at least two GI pathologists agreed on LGD, there was a significant association with progression (41%, p=0.04) and when all three GI pathologists agreed on a diagnosis of LGD, 80% progressed (p=0.012). In contrast, of patients with follow-up where there was no agreement between pathologists, none progressed.41 Patients within a randomized controlled trial evaluating radiofrequency ablation (RFA) vs surveillance for LGD in Europe were retrospectively analyzed by Duits et al., and they clearly shown that when three expert pathologists independently reviewed baseline and subsequent LGD biopsy specimens, the number of pathologists confirming LGD was strongly associated with progression to neoplasia and the risk for progression increased greatly when all three pathologists agreed on LGD.42

Therefore, the progression of LGD is proportional to histologic criteria and IOA of at least two GI pathologists with experience in BE.

Persistent confirmed LGDAs we mentioned, PC-LGD is defined as LGD present at both an index endoscopy as well as the first follow-up endoscopy. Three of four reviewed studies focused on the role of persistent LGD found PC-LGD to be a risk factor for progression. In the same study published by Duits et al., cited above,42 when LGD was detected at baseline and confirmed by the subsequent endoscopy, the odds of neoplastic progression were 9-fold increased in those patients who did not receive RFA. Other group of experts shown that in a large population-based cohort, patients with PC-LGD were at significantly higher risk of progression during follow-up, with an annual incidence rate (AIR) of 7.65 cases per 100 patient-years compared to only 2.32 cases per 100 patient-years for patients without PC-LGD.43 Similar results were found in a more recent study and concluded that PC-LGD could be used to risk stratify patients with LGD,44 whereas other study did not find a statistically significant association with PC-LGD and the risk of progression.37

These data suggest that when LGD is confirmed, patients with PC-LGD are at increased risk of progression.

Progression risk in patients with LGDInitial studies suggested that the risk of EAC development in BE patients with LGD is somewhere in between that of NDBE and HGD and BE patients with LGD have a low annual incidence of EAC, similar to NFD.37,45

A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies published in 2014, which was a mix of mostly unconfirmed LGD studies, showed that the pooled annual incidence rates of EAC alone and EAC and/or HGD in patients with LGD were 0.54% and 1.73% respectively. However, a subgroup analysis of 4 of the 24 included studies, based on whether the diagnosis was made by a single pathologist and after confirmation of LGD by an expert panel of pathologists, the former generally observed a lower incidence of progression (2.15%) than did the latter (5.7%).46 Nevertheless, another meta-analysis of 12 included studies conducted in order to evaluate the annual incidence of LGD progression to HGD and/or EAC when diagnosis was made by two or more expert pathologists, the authors found that among the total original LGD diagnoses, only 37.49% reached the consensus LGD diagnosis after review by two or more expert pathologists. Biopsies were obtained from four quadrants at, at-least, 2cm intervals all along the length of BE. Median follow up period was 50 months. In the pooled consensus LGD patients, the AIR of progression to HGD and/or EAC was 10.35%, and progression to EAC was 5.18% compared with 28.63% in patients with consensus HGD diagnosis. Among the patients downstaged from original LGD diagnosis to IFD and NFD, the AIR of progression to HGD and/or EAC was 1.42% and 0.65% respectively. When LGD is diagnosed by consensus agreement of two or more expert pathologists, its progression toward malignancy appears to be at least three times the current estimates and may be up to 20 times the current estimates.47

In the Surveillance versus Radiofrequency Ablation (SURF) trial, over a 3-year follow-up period, 26.5% of patients with LGD who underwent annual endoscopic surveillance progressed to HGD or EAC compared with just 1.5% of the treated group (with RFA). The main inclusion criteria in this study was a diagnosis of LGD confirmed by a central pathologist with extensive experience in BE.20 A recent report of the long-term outcomes of the SURF trial shown similar results after a median follow-up of 73 months.48

These finding and their analysis clarify that previous estimates of progression risk in LGD is artificially diminished, but when LGD is confirmed by expert pathologists, the risk of neoplastic progression in these patients is actually considerable.

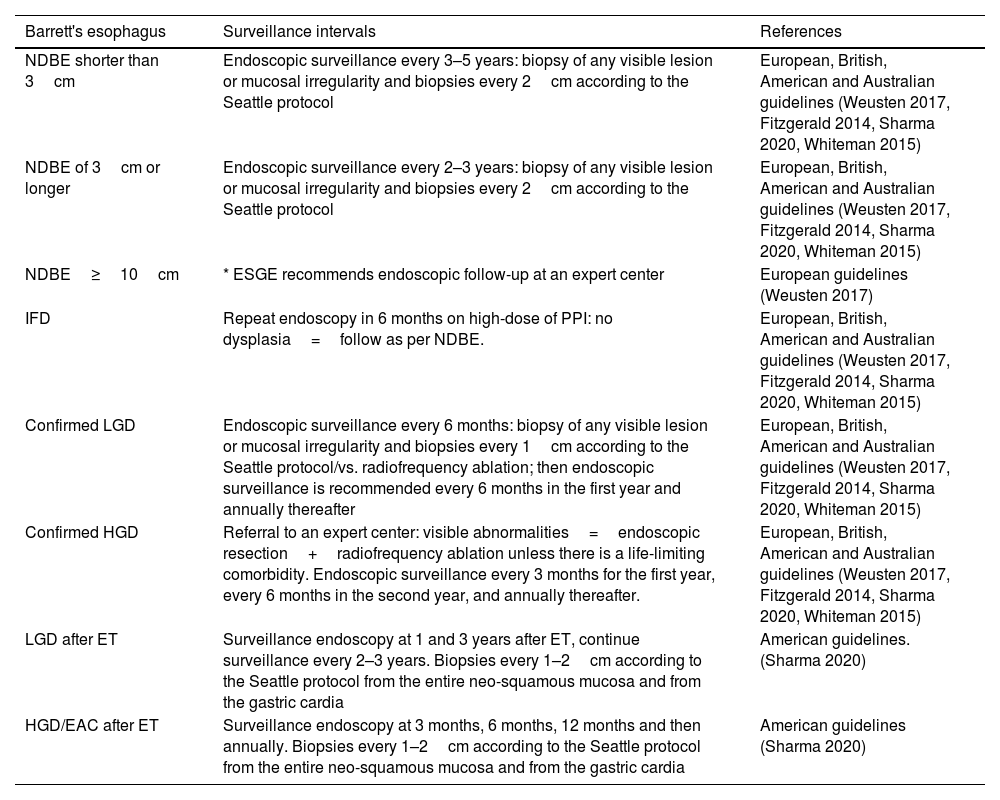

The European, British, American and Australian clinical guidelines for endoscopic surveillance consider the grade of dysplasia to determine the timing of surveillance.1–3,5 These guidelines also recommend biopsies of any visible lesion or mucosal irregularity and biopsies every 1–2cm according to the Seattle protocol. As for endoscopic surveillance after endoscopic therapy, the American Gastroenterological Association recommends a careful inspection of the neo-squamous mucosal and biopsies every 1–2cm according to the Seattle protocol from the entire neo-squamous mucosa and from the gastric cardia3 (Table 2).

Recommendations of western guidelines for endoscopic surveillance intervals in Barrett's esophagus.

| Barrett's esophagus | Surveillance intervals | References |

|---|---|---|

| NDBE shorter than 3cm | Endoscopic surveillance every 3–5 years: biopsy of any visible lesion or mucosal irregularity and biopsies every 2cm according to the Seattle protocol | European, British, American and Australian guidelines (Weusten 2017, Fitzgerald 2014, Sharma 2020, Whiteman 2015) |

| NDBE of 3cm or longer | Endoscopic surveillance every 2–3 years: biopsy of any visible lesion or mucosal irregularity and biopsies every 2cm according to the Seattle protocol | European, British, American and Australian guidelines (Weusten 2017, Fitzgerald 2014, Sharma 2020, Whiteman 2015) |

| NDBE≥10cm | * ESGE recommends endoscopic follow-up at an expert center | European guidelines (Weusten 2017) |

| IFD | Repeat endoscopy in 6 months on high-dose of PPI: no dysplasia=follow as per NDBE. | European, British, American and Australian guidelines (Weusten 2017, Fitzgerald 2014, Sharma 2020, Whiteman 2015) |

| Confirmed LGD | Endoscopic surveillance every 6 months: biopsy of any visible lesion or mucosal irregularity and biopsies every 1cm according to the Seattle protocol/vs. radiofrequency ablation; then endoscopic surveillance is recommended every 6 months in the first year and annually thereafter | European, British, American and Australian guidelines (Weusten 2017, Fitzgerald 2014, Sharma 2020, Whiteman 2015) |

| Confirmed HGD | Referral to an expert center: visible abnormalities=endoscopic resection+radiofrequency ablation unless there is a life-limiting comorbidity. Endoscopic surveillance every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months in the second year, and annually thereafter. | European, British, American and Australian guidelines (Weusten 2017, Fitzgerald 2014, Sharma 2020, Whiteman 2015) |

| LGD after ET | Surveillance endoscopy at 1 and 3 years after ET, continue surveillance every 2–3 years. Biopsies every 1–2cm according to the Seattle protocol from the entire neo-squamous mucosa and from the gastric cardia | American guidelines. (Sharma 2020) |

| HGD/EAC after ET | Surveillance endoscopy at 3 months, 6 months, 12 months and then annually. Biopsies every 1–2cm according to the Seattle protocol from the entire neo-squamous mucosa and from the gastric cardia | American guidelines (Sharma 2020) |

IM: intestinal metaplasia. NDBE: nondysplastic Barrett's esophagus. IFD: indefinite for dysplasia. LGD: low-grade dysplasia. HGD: high-grade dysplasia. ET: endoscopic therapy. EAC: esophageal adenocarcinoma. ESGE: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

On the other hand, the prevalence of BE and the risk of progression is less clear in Asia, for this reason the necessity of endoscopic surveillance of patients with BE in Asia is unclear.49,50

Final commentsLGD in BE remains a challenge to manage properly due to its highly variable natural course, its patchy distribution and the difficulties in making an easy and straightforward histologic diagnosis. Data suggest that: (1) Whereas adherence to the Seattle protocol is generally suboptimal, enough random biopsies within the Barrett's segment, after proper treatment of erosive esophagitis if present, is still essential to define diagnosis and avoid histopathologic confusion. (2) A careful review of specimens by an expert GI pathologist is crucial to confirm LGD diagnosis and avoid unnecessary treatment or inappropriately surveillance in BE patients. (3) If PC-LGD is found in one of the subsequent endoscopies, the patient should be offered first endoscopic ablation therapy or surveillance after shared decision making between him and the GI multidisciplinary team (Fig. 1).

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.