The presence of hepatolithiasis (HL) is prevalent in eastern countries. It is a clinical entity which is rarely reported in non-surgical series because the standard treatment is the surgical option. Currently, treatment has evolved, with the use of endoscopic techniques being increased and the number of hepatectomies being decreased.

SpyGlass™ is a small-calibre endoscopic direct cholangiopancreatoscopy developed to explore and perform procedures in the bile and pancreatic ducts. Single-operator peroral cholangioscopy (POC) is an endoscopic technique useful for treating difficult bile duct stones.

AimsTo assess the usefulness, efficacy, and safety of POC with the SpyGlass™ system in patients with HL. Primary objectives: to achieve technical success of the procedure and clinical success of patients with HL.

Study design and patientsRetrospective, single-centre cohort study of patients with HL from April 2012 to August 2018. SpyGlass™ was chosen in symptomatic patients referred from the surgery unit as the first-line procedure. To perform electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL), we used a Northgate Autolith IEHL generator with a 0.66-mm biliary probe.

ResultsWe performed a total of 13 procedures in 7 patients with HL. The mean age was 46 years (range 35–65) and 3/7 of patients were female. We achieved technical success in 5/7 cases (71.4%) and clinical success in 4/7 cases (57%).

DiscussionSpyGlass™ is safe and effective in the treatment of HL. With these results, we confirm the need for management of patients with HL in a multidisciplinary team. When the endoscopic approach is the option, this procedure must be performed by experts in advanced endoscopy.

La presencia de hepatolitiasis (HL) es frecuente en los países orientales. Es una entidad poco descrita en series no-quirúrgicas. El tratamiento estándar para esta entidad es la opción quirúrgica. Actualmente el tratamiento ha evolucionado, aumentando el uso de técnicas endoscópicas y disminuyendo el número de resecciones hepáticas quirúrgicas. SpyGlass™ es un colangiopancreatoscopio endoscópico directo de pequeño calibre desarrollado para explorar y realizar procedimientos en el conducto biliar y pancreático. La colangioscopia peroral de operador único (POC) es una técnica endoscópica útil para tratar los cálculos complejos de las vías biliares.

ObjetivosEvaluar la utilidad, la eficacia y la seguridad de la colangioscopia POC con el sistema SpyGlass™ en pacientes con HL. Objetivos primarios: éxito técnico del procedimiento y el éxito clínico de pacientes con HL.

Diseñodel estudio y pacientes Estudio de cohorte retrospectivo, unicéntrico de pacientes con HL desde abril de 2012 hasta agosto de 2018. SpyGlass™ fue elegido en pacientes sintomáticos remitidos desde la unidad de cirugía como procedimiento de primera línea. Para realizar litotricia electrohidráulica (EHL) se utilizó un generador Northgate Autolith® IEHL con una sonda biliar de 0,66mm.

ResultadosSe incluyó en el estudio un total de 13 procedimientos en 7 pacientes con HL. La edad media fue de 46 años (rango: 35-65) y 3/7 de los pacientes eran mujeres. Se logró éxito técnico en 5/7 casos (71,4%) y éxito clínico en 4/7 casos (57%).

DiscusiónSpyGlass™ es seguro y efectivo en el tratamiento de HL. Con estos resultados, confirmamos la necesidad del manejo de pacientes con HL en un grupo multidisciplinar. Cuando el enfoque endoscópico es opción, este procedimiento debe realizarse para endoscopistas avanzados expertos.

The presence of lithiasis in the intrahepatic biliary tree, also known as hepatolithiasis (HL) is prevalent in eastern countries.1,2 These patients usually present recurrent episodes of cholangitis. The primary treatment is used to resolve ongoing infections and to prevent recurrent cholangitis, subsequent hepatic fibrosis, and progression to cholangiocarcinoma.3 Studies have reported that hepatectomy is indicated for treatment of HL in: (a) unilobar HL, and particularly that on the left; (b) atrophy or severe fibrosis of the affected liver segments or lobe; (c) presence of a liver abscess; (d) cholangiocarcinoma; and (f) multiple intrahepatic stones causing marked biliary stricture or dilation.4–6

The gold standard treatment for HL is surgical hepatectomy. However, when the stones obstructed in certain segment of liver, the hepatectomy is technically difficult.7 Risk factors for HL have been little studied.8 Even more, for patients without biliary stenosis or normal liver volume, an optimal treatment includes minimal invasion, faster recovery and most preservation of uninvolved liver.

Even after effective treatment, complications associated with HL frequently occur. Short term complications include recurrent cholangitis, hepatic cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma. Long-term complications include concurrent biliary stricture, or long-standing cholangitis.9,10

The treatment for HL has evolved, currently a conservative approach is being attempted, increasing the use of endoscopic techniques and decreasing the number of hepatectomies performed by this disease.11,12

Peroral single-operator cholangioscopy (POC) is an endoscopic technique useful for treating complex bile and pancreatic duct stones.13,14 In 2015, the upgraded SpyGlass™ Digital System (DS; Boston Scientific Corp) was released. Compared to its legacy version, the DS has a digital sensor with 4-fold higher resolution, a 60% wider field of view, automatic light control, and LED illumination.15

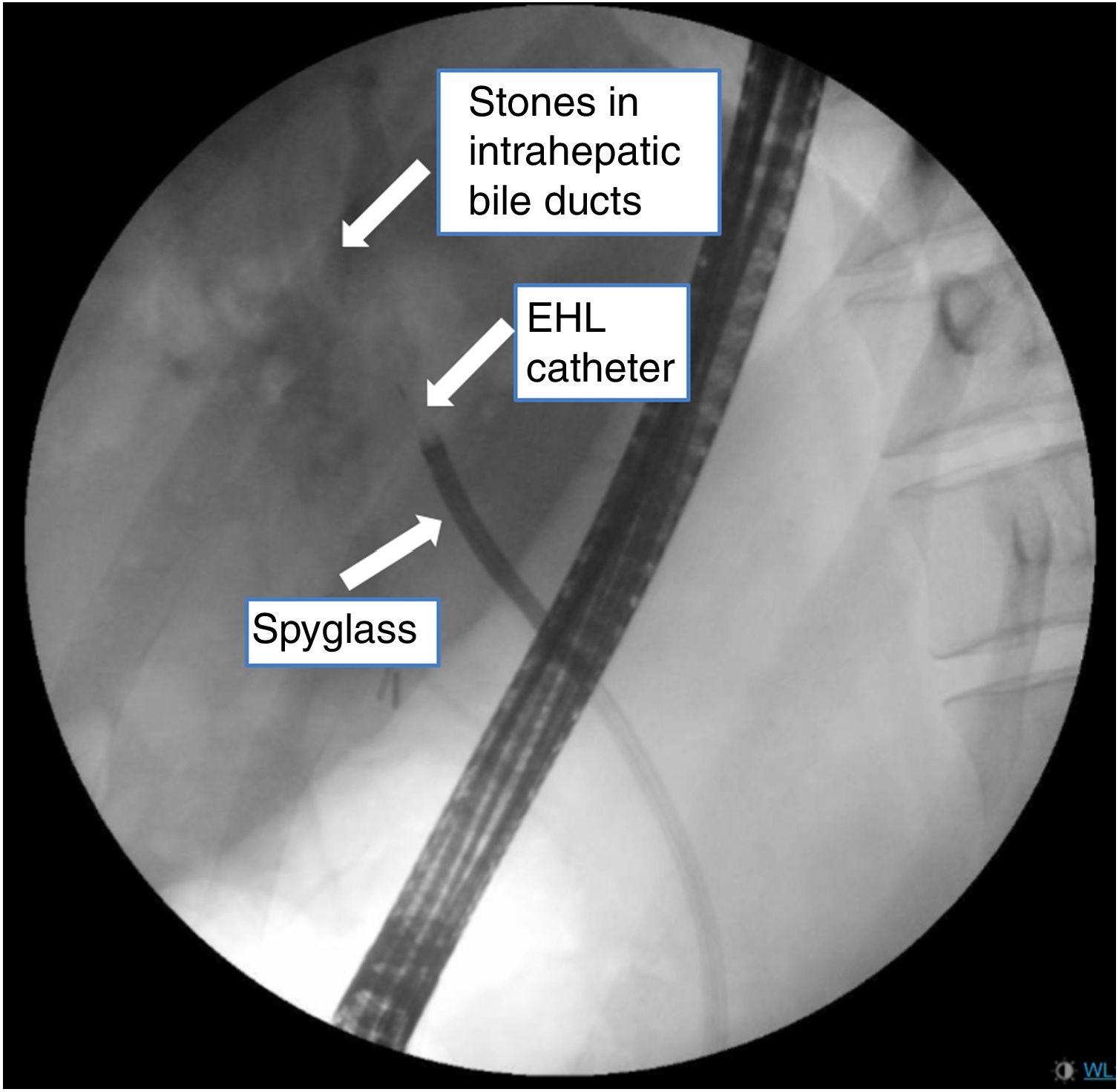

The current indications for POC included: indeterminate biliary strictures, management of biliary stones, biliary duct obstruction, surveillance of dominant stricture in primary sclerosing cholangitis, staging of cholangiocarcinoma, evaluating biliary cysts, and removal of stents.16 The use of POC as only treatment in regional HL without stricture with successful results have been reported (Fig. 1).17,18

The aim of this study is to assess the usefulness, efficacy, and safety of POC with the SpyGlass™ system in the management of HL.

Materials and methodsStudy design and patientsRetrospective, single-centre cohort study of patients with HL who were referred to our endoscopic unit for ERCP with POC from April 2012 to August 2018. SpyGlass™ was chosen in symptomatic patients referred from surgery unit as first-line procedure for therapeutic management of large stones in the intrahepatic biliary tree with MRI/CT findings indicating that ERCP with POC could be successful (Fig. 1).

Number of stones are defined for the presence in MRI/TC findings and/or cholangiogram findings during the ERCP. Patients were classified in three groups: (a) <3 stones, (b) between 3 and 10 stones and (c) more than 10 stones. Size of stones is defined in millimetres by the description on the MRI/CT or cholangiogram findings.

EndoscopistAll the procedures were performed by one senior endoscopist who had experience with POC.

Equipment and techniqueThe SpyGlass™ Legacy System was used to perform POC between April 2012 and March 2015, and the DS device was used from April 2015 to August 2018.

For electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL), we used a Northgate Autolith IEHL generator with a 0.66mm biliary probe (Northgate Technologies Inc). Lithotripsy treatments were performed initially with a generator setting of 10 pulses per second and a power output of 60W. Power output was adjusted upwards as needed, to a maximum of 100W. All procedures were performed under deep sedation, which was controlled by an anaesthetist, and with the patient lying in a left lateral position. Intravenous antibiotics were administered in all cases. Biliary sphincterotomy was performed in all cases in which it had not been performed previously. To perform POC, The SpyScope was inserted through the therapeutic duodenoscope (TJF-180V; Olympus) working channel, and advanced into the bile duct. The SpyGlass™ was then inserted through the catheter channel. Although we required a guidewire to insert the older POC system into the bile duct in most cases, direct biliary cannulation without the need for a guidewire was achieved in some cases with the DS system. While the system was being inserted into the bile duct through the papilla (with direct endoscopic and radiological imaging), aspiration of detritus and irrigation with sterile saline was required (Video 1).

Primary outcomesThe primary study outcomes were to achieve technical success of the procedure and clinical success of these patients. Technical success was defined as the ability to reach to the HL with de POC system and correct application of EHL. Clinical success was defined as the patient symptom's reduction (episodes of acute cholangitis) or surgical free follow up (Fig. 2).

Secondary outcomesAdditional secondary outcomes included total procedure time, total POC time and reduction or disappearance of HL. The total procedure time was measured from the time of the duodenoscope insertion to its withdrawal and included the time required to perform the ERCP with POC.

Safety and adverse events were prospectively evaluated either at the end of the procedure or during the follow-up within first month.

Statistical analysisAs we are presenting a small size of patients, we only applied descriptive statistics.

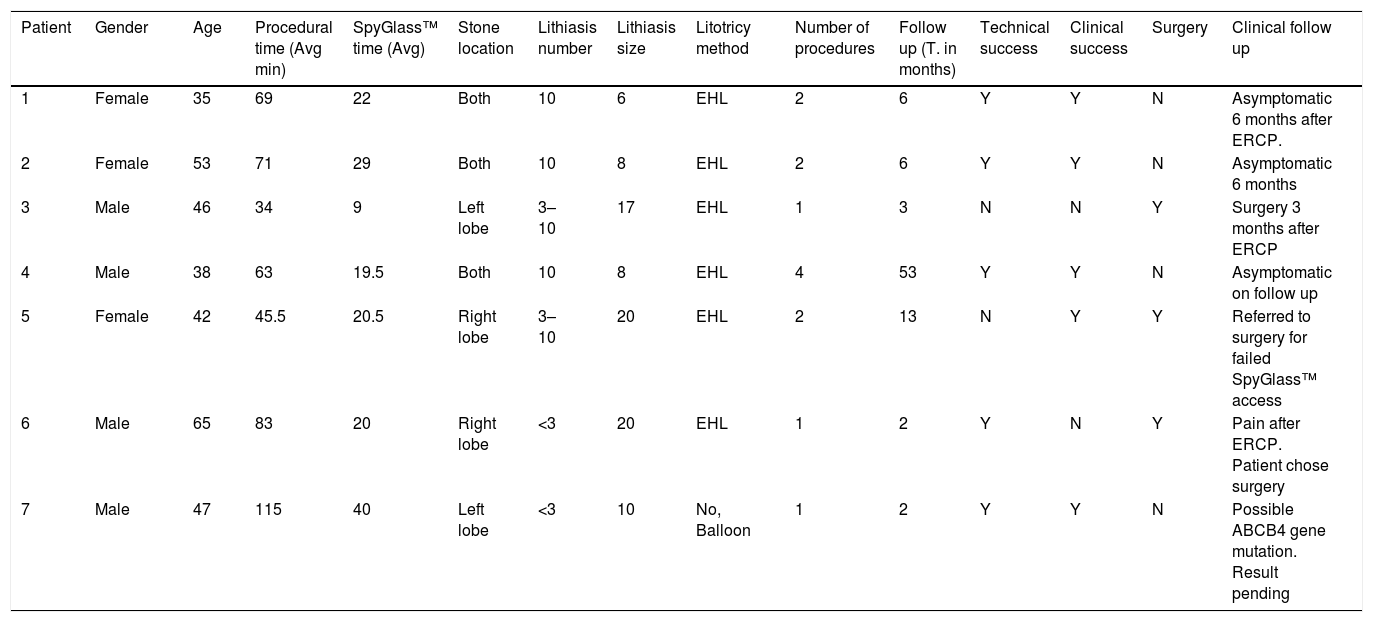

ResultsPatient characteristicsThe final study group consisted of seven patients, including four men (57.1%) and three women (42.9%), with a median age of 46 (interquartile range, 35–65) years. Intrahepatic SpyGlass™ was applied in all patients were symptomatic intrahepatic stones was diagnosed in Gastroenterology and surgery unit. Among them, a total of 13 procedures of ERCP with POC were performed between April 2012 and August 2018. In this series we use SpyGlass™ legacy in nine procedures from 2012 and we started the use of SpyGlass™ DS with 4 patients of this group. We achieved technical success in 5/7 cases (71.4%) and clinical success in 4/7 cases (57%). The incidence of adverse events was 1/13 (7.7%) consisted in one episode of acute mild cholangitis post procedure and there were no differences between the DS and the legacy system. The most relevant results are shown in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and procedure results.

| Patient | Gender | Age | Procedural time (Avg min) | SpyGlass™ time (Avg) | Stone location | Lithiasis number | Lithiasis size | Litotricy method | Number of procedures | Follow up (T. in months) | Technical success | Clinical success | Surgery | Clinical follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 35 | 69 | 22 | Both | 10 | 6 | EHL | 2 | 6 | Y | Y | N | Asymptomatic 6 months after ERCP. |

| 2 | Female | 53 | 71 | 29 | Both | 10 | 8 | EHL | 2 | 6 | Y | Y | N | Asymptomatic 6 months |

| 3 | Male | 46 | 34 | 9 | Left lobe | 3–10 | 17 | EHL | 1 | 3 | N | N | Y | Surgery 3 months after ERCP |

| 4 | Male | 38 | 63 | 19.5 | Both | 10 | 8 | EHL | 4 | 53 | Y | Y | N | Asymptomatic on follow up |

| 5 | Female | 42 | 45.5 | 20.5 | Right lobe | 3–10 | 20 | EHL | 2 | 13 | N | Y | Y | Referred to surgery for failed SpyGlass™ access |

| 6 | Male | 65 | 83 | 20 | Right lobe | <3 | 20 | EHL | 1 | 2 | Y | N | Y | Pain after ERCP. Patient chose surgery |

| 7 | Male | 47 | 115 | 40 | Left lobe | <3 | 10 | No, Balloon | 1 | 2 | Y | Y | N | Possible ABCB4 gene mutation. Result pending |

Currently, the surgical approach is the standard care for these patients. The principles of primary HL treatment are to remove all biliary stones, to establish adequate drainage of the obstructed biliary system, and to resect atrophic liver parenchyma, which harbour bacteria and serve as a focus of infection.19 Hepatectomy that can clean all the intra-hepatic ductal stones and remove strictured bile ducts within the resected liver segment(s), reducing the subsequent risks of recurrent stones and cholangiocarcinoma, seems to be the definitive and effective approach for this disease in selected patients.20

There are many concerns about hepatectomy. First, bleeding control during the liver parenchyma dissection and possible ischaemic insult of the remnant liver.21 Technically, Laparoscopic right-sided hemihepatectomy for HL is described more complicated than the left side for its repeated inflammation and perihepatic adhesions. It is only performed in a limited number of cases by experienced laparoscopic surgeons. Because of repeated infection of biliary tract and atrophy of liver parenchyma caused by intra-hepatic stones, there are many postoperative complications associated with HL. Wound infection is the most common complication of HL after hepatectomy, but laparoscopic approach can reduce it sufficiently due to the small incisions and the incidence of bile leakage is less in laparoscopic procedures22 and last, HL with secondary biliary liver cirrhosis in patients with end-stage liver disease is indicated for liver transplantation.23

With this scenario the treatment which have the advantage of minimal invasion, faster recovery and most preservation of uninvolved liver is a burning desire. POC can provide images of distal ducts as well as guidance of treatment under direct vision, which helps in diagnosis and therapy of HL. Only few reports about HL treatment with SpyGlass™ have been report.24

However, in patients with poor condition and complicated hepatolithiasis, such as when calculi are located bilobarly or diffusely, it is impossible to attain complete clearance,25 and further postoperative POC is always needed as an alternative treatment. POC is a supportive method for the active management of HL and is associated with reduced rates of residual stones and reoperation.26 During POC, endoscopist may be faced locating the exact position of the calculi, and identifying an accurate pathway for the cholangioscope, especially in complicated HL.

Although our series is small, our results show that SpyGlass™ is safe and effective in the treatment of HL. We have not reported major incidents, without intraprocedural bleeding or later complications. We have had a success rate greater than 60% with treatments performed in both liver segments and in several cases with multilobar stones. Only one patient in our series presented stones were deemed not amenable to endoscopy, and two patients chose surgical method after SpyGlass™ with EHL.

Our study also has other limitations. First, it is inherently limited by its retrospective nature. Second, the study involved a small number of patients, and it was performed at a single medical centre, and thus, our results may not be representative of the general population. Third, we missed one patient in the follow up. Forth, we could not evaluate the incidence of cholangiocarcinoma and the residual stone rate could have been affected by bias, as is suggested by a lower incidence of cholangiocarcinoma and a higher residual stone rate than have been previously reported.10 According to this data, further studies are needed to explore more endoscopic results in this group of patients.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.