Overlap syndrome is a condition characterized by the coexistence of features belonging to different nosographic disorders within the spectrum of autoimmune liver diseases: autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).1,2 Although the most frequent associations in overlap syndrome are between AIH and PBC3 and, with a lower prevalence, AIH and PSC, rare cases of PBC and PSC4–9 have also been reported in the literature.

A 66-year-old woman was referred to our clinic in 2010 due to fatigue, pruritus and abnormal hepatic enzymes serum levels; BMI was 22.5. She also denied alcohol intake and drugs assumption.

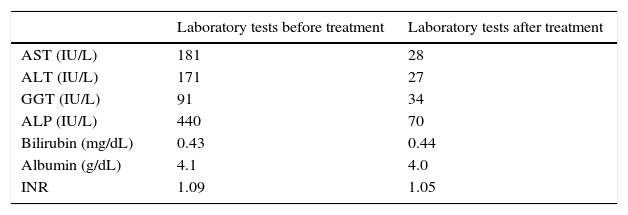

Liver enzymes have been normal until 1 year before the observation. Since then until the time of the first observation in our clinic, laboratory tests always remained persistently abnormal: AST: 181IU/L (N<32); ALT: 171IU/L (N<31); gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT): 91IU/L (N: 5–36); alkaline phosphatase (ALP): 440U/L (N: 35–120); bilirubin: 0.43mg/dL (N: 0.20–1.10); albumin: 4.1g/dL (N: 3.5–5.3); INR: 1.09 (N: <1.25). CEA and CA 19-9 were normal.

Ultrasound examination excluded morphological features of advanced liver disease and alterations of the biliary tract.

The diagnostic work-up showed that viral serological screen was negative for HAV, HBV, HCV, HIV, CMV and EBV. No signs of insulin resistance (Homa index: 2.2) and storage liver diseases (iron, copper and alpha-1 antitrypsin in particular) were detected.

Autoimmune profile tested by indirect immunofluorescence showed a positivity for anti-nuclear (ANA) (titre: 1:640, speckled and multiple nuclear dots patterns), anti-mitochondrial (AMA) (titre: 1:80) and anti Sp-100 antibodies. A slight positivity for anti-smooth muscle antibody (pattern SMA V) was detected. All the other autoimmune tests resulted negative.

Levels of immunoglobulins showed a slight increase in IgM class (285mg/dL, N: 40–230), while IgG levels were within the normal range.

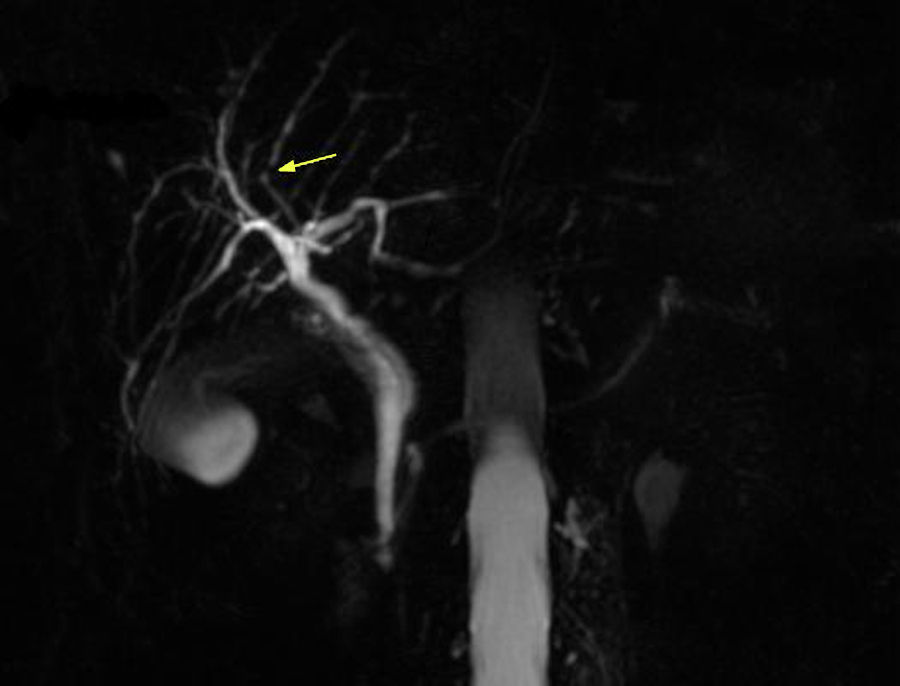

We performed magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) that showed intrahepatic bile ducts with irregular profiles and slight concentric wall thickening without a dominant stricture.

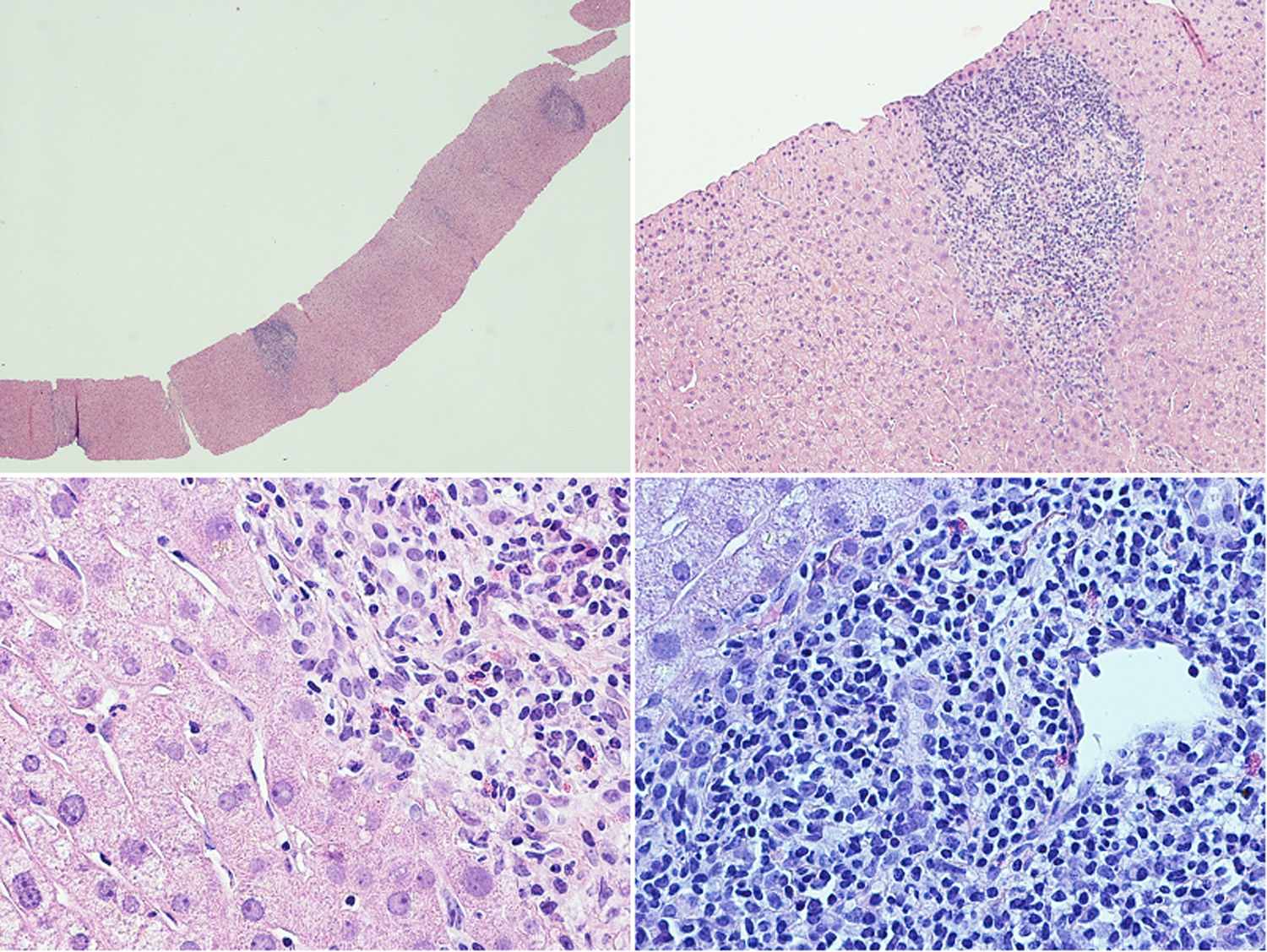

A liver biopsy was performed in order to complete the diagnostic work-up (Fig. 1): the liver tissue specimen showed a moderate lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate with poor eosinophilic component; no evidence of significant fibrosis; bile ducts were attacked in several tracts by lymphocytic cells; there was evidence of interface hepatitis and ductular proliferations. The overall picture showed chronic hepatitis features with moderate interface hepatitis (grade 3 in Ishack classification) and biliary aggression; no evidence of portal and lobular granulomas and hepatocytic rosetting. The pathologist was unable to reach a definitive diagnosis, since these findings can be found both in PCB and in PSC.

Liver histological examination. The liver tissue specimen, with a sufficient number of portal spaces, show a moderate lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate with poor eosinophilic component; bile ducts were attacked in several tracts by lymphocytic cells with evidence of interface hepatitis and ductular proliferations. No evidence of significant fibrosis.

Considering the histological and biochemical results, which were suggestive of PBC, we decided to treat the patient only with high dose of UDCA (20mg/kg/die) with good clinical and biochemical response (Table 1).

In 2012 a further MRCP was performed due to the previous finding of the minimal irregularities of the intrahepatic biliary tree, documenting the developing of a dominant stricture on the bile duct in the fourth liver segment (Fig. 2) while common bile duct was normal. Biochemical parameters and tumoral markers (in particular CEA and CA 19-9) were still within the normal range. Also Mayo Clinic risk score for PSC was substantially stable (around 0) during the 5 years follow-up period.

A MRCP performed in 2015 confirmed the previous findings, and in particular the presence, unchanged in size, of the biliary stenosis.

PBC/PSC overlap syndrome is a rare condition, reported in literature in only few other cases,4–9 some of them quite controversial and diagnosed with old imaging techniques.

The clinical phenotype of our patient satisfied all the diagnostic criteria for PBC, in particular the increased of ALP, GGT and IgM class levels, the auto-antibody profile (AMA and anti-Sp100 antibody were positive) and the liver histology.

The finding of slight irregularities of the bile ducts suggest us to perform periodical MRCPs for a period of 5 years with the detection of a progressive deterioration of the morphology of the biliary tract with the appearance of a dominant stricture on the bile duct in the fourth liver segment, despite UDCA therapy, suggestive of PSC.

Considering the PBC as the dominant clinical phenotype, we treated the patient with UDCA (20mg/kg/die) with a complete biochemical response (liver enzymes were normal after 1 year of UDCA treatment).

Despite the overlap between PBC and PSC does not modify the therapeutic choice, it is important to perform a close follow-up due to the increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma, whose annually risk is 1–2% in PSC patients10.

The case we describe is the first reporting a follow-up period of 5 years: our case, however, differs from the others4–9 for the stability of the disease; during the follow-up period no signs of decompensated liver disease have been described. Furthermore in this period the patient veered to a condition of PSC with the development of a dominant stricture, without progression in the last years.

In conclusion we usually apply some rigid and schematic diagnostic criteria in clinical practice to distinguish PBC, PSC and AIH. More likely however we should consider these diseases as a continuum in the spectrum of autoimmune liver disorders, each one with its particular features.

Financial supportNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors who have taken part in this study declare that they have no disclosure regarding funding or conflict of interest.