Casos Clínicos en Gastroenterología y Hepatología

Más datosCOVID-19 vaccine has recently been related to few cases of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH),1–3 raising the question whether there exists a causal relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and the development of AIH in predisposed patients. Several autoimmune diseases have been reported in association with vaccines. In fact, AIH triggered by vaccination for other diseases has also been described.4

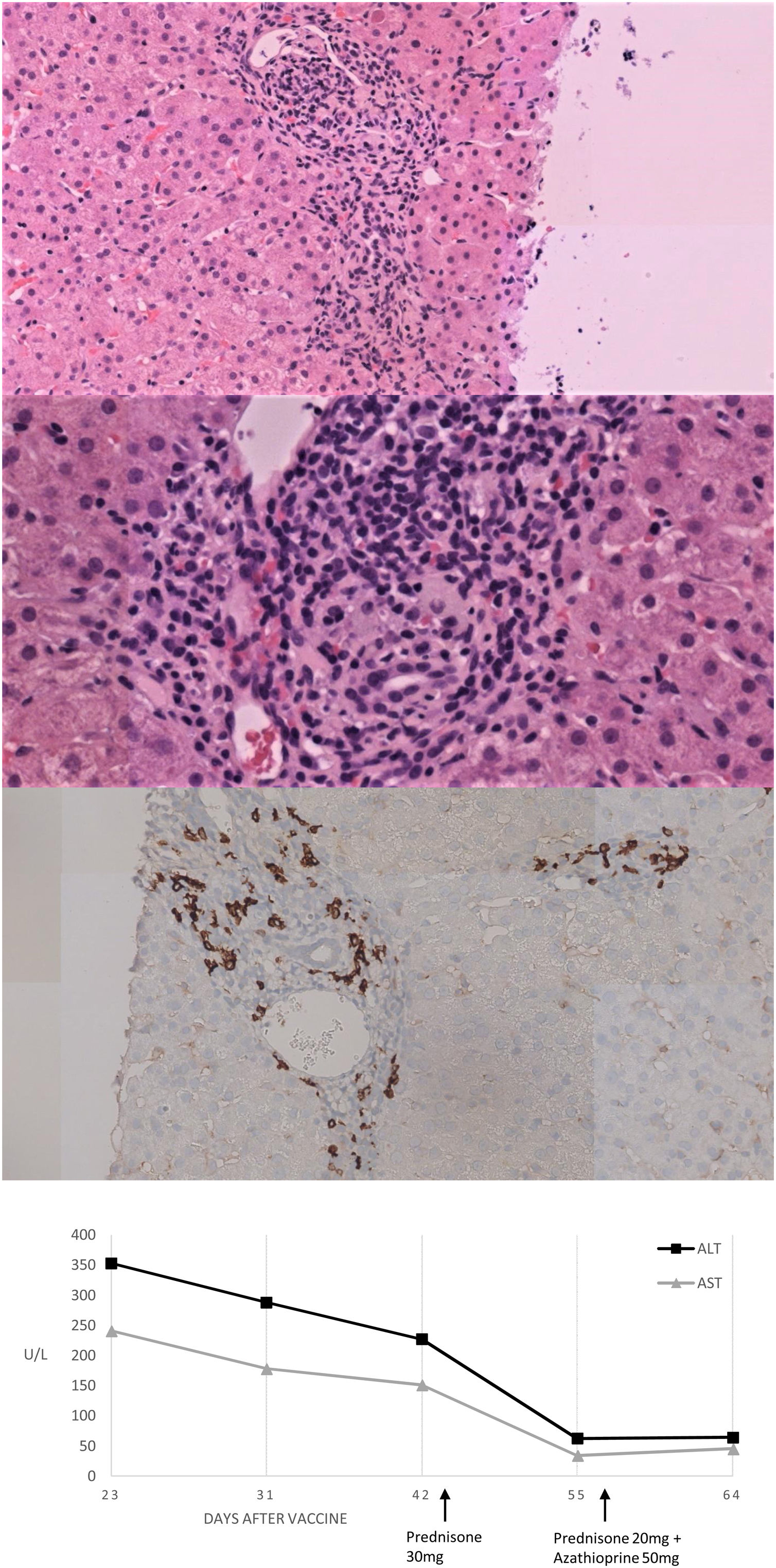

We present herein a 46-year-old Caucasian woman that was sent to the hepatology clinics of our hospital in January 2018 for mild hypertransaminasemia. She had a medical history of hypothyroidism treated with levothyroxine, and chronic iron deficiency anemia which had been attributed to menstrual bleeding. The patient was asymptomatic but a routine blood test found AST 122U/L, ALT 157U/L with normal GGT, alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin; hemoglobin 9.3g/dL, with normal coagulation. Abdominal ultrasound was normal and serologies were negative for hepatitis A, B and C, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 and 2, varicella-zoster virus (VVZ) and HIV. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) was positive (1:160; rods and rings pattern). Other antibodies (i.e. anti-mitochondrial, anti-smooth muscle, liver-kidney microsomal, antitransglutaminase) were negative. Serum protein electrophoresis showed gammaglobulin of 19.9%. Iron deficiency was found, with a ferritin of 8.4ng/mL and a transferrin saturation of 4.8%. Ceruloplasmin, TSH and immunoglobulins were normal. Due to chronic anemia, mild inespecific gastrointestinal symptoms in the past and abnormal liver function tests, an upper GI endoscopy was performed with duodenal biopsies showing normal villi with not raised intraepithelial CD3+ lymphocites. Genetic study resulted positive HLA-DRB1*03 and 04, indicating a susceptibility to AIH, and positive HLA DQ2 and DQ8 for celiac disease. Transient elastography result was 7.8KPa. We followed the patient in our hepatology clinic with routine blood tests every six months, always finding normal liver function tests during a 2-year follow-up. The patient received the first Vaxzevria COVID-19 vaccine on March 2021. In a scheduled control with laboratory test performed 3 weeks after vaccination we found AST 241U/L, ALT 353U/L, GGT 44U/L and alkaline phosphatase 135U/L with normal bilirubin and coagulation. Total IgG was 2016mg/dL. Viral acute hepatitis was ruled out and there was no history of exposure to hepatotoxic drugs. A liver biopsy was performed and the findings were compatible with AIH (Fig. 1A–C). The Revised Original Score for AIH pretreatment was 18 and the simplified criteria for the diagnosis of AIH was 7, both indicating definite AIH. Prednisone was initiated at a dose of 30mg daily with a rapid improvement after 2 weeks of treatment (Fig. 1D), so prednisone was tapered to 20mg and azathioprine was added to treatment at a dose of 50mg daily.

Histological and biochemical findings. (A, B) H&E stain low-magnification (×20 and ×40 respectively) shows lymphoplasmacytic portal infiltrate with focal disruption of the limiting plate. No evidence was found of histologic cholestasis, fibrosis or iron deposit. (C) Immunohistochemical study of plasma cells expressing CD38. (D) Biochemical trend of plasma ALT and AST over time.

Recently, immune thrombocytopenia cases developing after vaccination for this disease have been published, suggesting that COVID-19 vaccines may induce autoimmune diseases.5 In the last few months some cases of AIH after COVID-19 vaccination have been published, related to both mRNA vaccines1,2 and viral-vector vaccines.3 Our patient presented with acute AIH following Vaxzevria COVID-19 vaccine, a viral vector vaccine. Special consideration deserves the fact that in this case there was a previous medical history of abnormal liver function tests 2 years before with spontaneous normalization, and a positive genetic study for AIH predisposition, so it is probable that the patient had an AIH controlled without treatment and the vaccine triggered a flare of the disease. However, we cannot prove whether COVID-19 vaccine was the trigger of a new bout of AIH or if it is a casual association. Moreover, it could be a case of drug induced autoimmune liver disease (DIALD), as the histology is no pathognomonic distinguishing DIALD and AIH. In regard with this, our patient has initiated azathioprine and is tapering prednisone, so additional follow up will be crucial to better understand the process.

To sum up, we present the case of a 46-year-old woman with a probable AIH controlled without treatment, who presented with a flare of the disease after COVID-19 vaccination. Distinguishing vaccine-induced autoimmune liver disease from coincidental autoimmune liver disease presenting soon after vaccination is not possible at this time. The report of this case reinforces the message that vaccines against COVID-19 could either induce AIH or lead to a flare of the disease, and should encourage us to remain vigilant.

Authors’ contributionsST: writing of the manuscript and revision of the final version of the manuscript. AC: patient care and revision of the final version of the manuscript. MG: pathology reading and revision of the final version of the manuscript. EZ: patient care and revision of the final version of the manuscript.

Financial supportNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.