Health-related quality of life (HRQL) assessed by a specific, validated, brief test is an important measure of the health status perceived by patients diagnosed with chronic liver disease.

AimTo prospectively validate the SF-LDQOL (Short Form-Liver Disease Quality of Life) instrument in Spanish, in patients diagnosed with liver disease of diverse etiologies and distinct severity levels, attended at the Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge (Barcelona).

MethodsThis observational, longitudinal study was conducted by using the SF-LDQOL in outpatients diagnosed with chronic liver disease. This instrument contains the generic SF-36 test, and 9 liver disease-specific dimensions. We also evaluated socio-demographic features, the number of missing responses, and internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha), as well as Pearson's correlation between SF-36 and SF-LDQOL scores on specific dimensions by means of a multi-trait multi-method technique. The sample consisted of 340 patients.

ResultsIn 6 out of 9 liver disease-specific dimensions, reliability coefficients for internal consistency exceeded 0.70. The convergent validity of these items was acceptable in 8 out of 9 dimensions, with a scaling success of 100% in each item. Missing items were under 1.5% in all dimensions, except for Sexual Functioning.

ConclusionsThe Spanish version of the SF-LDQOL has, in general, good psychometric properties, making it a useful instrument for clinical practice in a population of patients diagnosed with chronic liver disease, with or without liver transplantation.

La calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) evaluada con un test específico, validado y breve es una medida importante del estado de salud percibida por los pacientes diagnosticados de hepatopatía crónica.

ObjetivoValidar de forma prospectiva el SF-LDQOL (Short Form-Liver Disease Quality of Life) en lengua española, en pacientes con hepatopatías de diversa etiología y gravedad, atendidos en el Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge.

MétodosEstudio observacional y longitudinal, en pacientes ambulatorios con hepatopatía crónica. Se administró el SF-LDQOL, que contiene el test genérico SF-36 y el test específico SF-LDQOL. Igualmente se evaluaron las características sociodemográficas, el número de respuestas en blanco, así como la fiabilidad de la consistencia interna (alpha de Cronbach) y la correlación de Pearson entre las puntuaciones del SF-36 y las del SF-LDQOL mediante la técnica de multi-rasgo multi-método. La muestra fue de 340 pacientes.

Resultados6 de las 9 dimensiones específicas de enfermedad hepática obtuvieron coeficientes de fiabilidad alfa para la consistencia interna superiores a 0,7; la validez convergente de estos ítems fue aceptable en 8 de las 9 dimensiones, con un éxito de escalaje del 100%. El porcentaje de ítems en blanco fue inferior al 1,5% en todas las dimensiones excepto Funcionamiento Sexual.

ConclusionesEl SF-LDQOL en lengua española cuenta con buenas propiedades psicométricas y se convierte en un instrumento útil para la práctica clínica diaria en pacientes diagnosticados de hepatopatía crónica, con o sin trasplante hepático.

Chronic liver disease is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in Spain. The most common aetiologies are: hepatitis B infection, hepatitis C infection and alcoholic liver disease. Other causes, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, or metabolic causes, such haemochromatosis or Wilson's disease, are less common. All forms of liver disease that cannot be treated in the short- or medium-term usually become chronic, with progressive hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis, and in some cases hepatocellular carcinoma.

Both the liver disease itself and the drugs used to treat it can affect a patient's health-related quality of life (HRQOL),1 as has been shown in studies in fatigue among hepatitis C patients,2 or in liver damage caused by excess alcohol intake.3–5 HRQOL is the individual's subjective feeling of well being and ability to perform activities of daily living, and. HRQOL assessment is an increasingly important outcome measure in the comprehensive management of patients with chronic liver disease.6 It is measured on the basis of information provided by patients themselves, who are in the best position to report their symptoms and the limitations these cause. A good HRQOL is now a target outcome following treatment to prolong survival in several diseases, including chronic liver disease and liver transplant,7 and interest in this instrument is growing. In one of the few studies exploring whether quality of life scores can predict survival, Gao et al.8 found that the short form 36-item HRQOL questionnaire (SF-36) can predict survival in patients with chronic liver disease.

Using HRQOL to evaluate patients with chronic liver disease can have a positive effect on quality of life by improving therapeutic compliance in some groups,9 and establishing better communication between patients and medical staff.

HRQOL questionnaires are divided into 2 categories: generic and specific. Among the generic questionnaires, the SF-36 is the most frequently used.10–12 Another HRQOL questionnaire, the SF-12, an abbreviated version of the SF-36, has been used to evaluate quality of life in patients with liver disease.13 Specific questionnaires focus, as the name suggests, on specific diseases. In the case of liver disease, the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ)14 is used by some researchers,15 while others use the Liver Disease Quality of Life (LDQOL)16 questionnaire, which includes the SF-36 and a further 75 items relating to liver disease, grouped into 12 domains. The Spanish version of the LDQOL questionnaire was validated by Casanovas et al.17 Several researchers have previously used the SF-36 to evaluate quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease.18,19 Quality of life questionnaires are not currently used in routine clinical practice, most probably because they are too long to be administered during a standard medical consultation. This has raised the need for more abbreviated instruments that are equally valid, but take less time to administer and are less tiring for the patient. The short English version of the LDQOL (SF-LDQOL), validated by Kanwal,20 was designed for just this purpose.

The need has now arisen for a validated Spanish version of the SF-LDQOL, adapted to the time constraints of medical consultations in Spain.

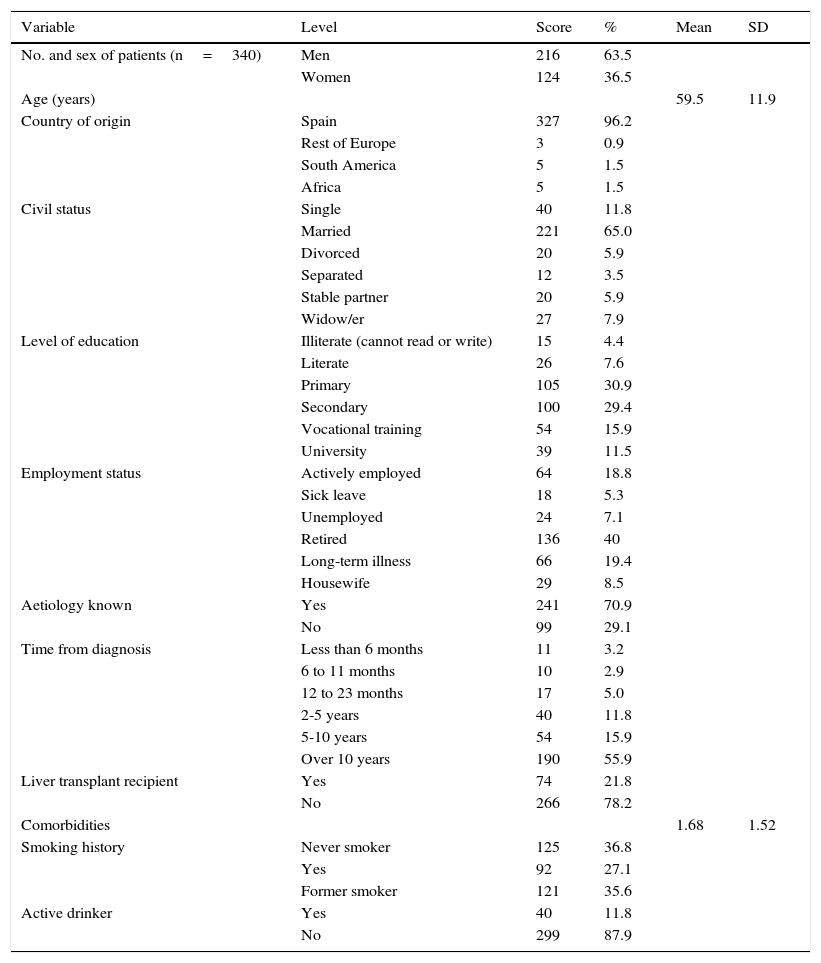

MethodsStudy cohortTables 1 and 2 summarise the demographic and clinical characteristics of study patients.

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients (n=340).

| Variable | Level | Score | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. and sex of patients (n=340) | Men | 216 | 63.5 | ||

| Women | 124 | 36.5 | |||

| Age (years) | 59.5 | 11.9 | |||

| Country of origin | Spain | 327 | 96.2 | ||

| Rest of Europe | 3 | 0.9 | |||

| South America | 5 | 1.5 | |||

| Africa | 5 | 1.5 | |||

| Civil status | Single | 40 | 11.8 | ||

| Married | 221 | 65.0 | |||

| Divorced | 20 | 5.9 | |||

| Separated | 12 | 3.5 | |||

| Stable partner | 20 | 5.9 | |||

| Widow/er | 27 | 7.9 | |||

| Level of education | Illiterate (cannot read or write) | 15 | 4.4 | ||

| Literate | 26 | 7.6 | |||

| Primary | 105 | 30.9 | |||

| Secondary | 100 | 29.4 | |||

| Vocational training | 54 | 15.9 | |||

| University | 39 | 11.5 | |||

| Employment status | Actively employed | 64 | 18.8 | ||

| Sick leave | 18 | 5.3 | |||

| Unemployed | 24 | 7.1 | |||

| Retired | 136 | 40 | |||

| Long-term illness | 66 | 19.4 | |||

| Housewife | 29 | 8.5 | |||

| Aetiology known | Yes | 241 | 70.9 | ||

| No | 99 | 29.1 | |||

| Time from diagnosis | Less than 6 months | 11 | 3.2 | ||

| 6 to 11 months | 10 | 2.9 | |||

| 12 to 23 months | 17 | 5.0 | |||

| 2-5 years | 40 | 11.8 | |||

| 5-10 years | 54 | 15.9 | |||

| Over 10 years | 190 | 55.9 | |||

| Liver transplant recipient | Yes | 74 | 21.8 | ||

| No | 266 | 78.2 | |||

| Comorbidities | 1.68 | 1.52 | |||

| Smoking history | Never smoker | 125 | 36.8 | ||

| Yes | 92 | 27.1 | |||

| Former smoker | 121 | 35.6 | |||

| Active drinker | Yes | 40 | 11.8 | ||

| No | 299 | 87.9 |

SD: standard deviation.

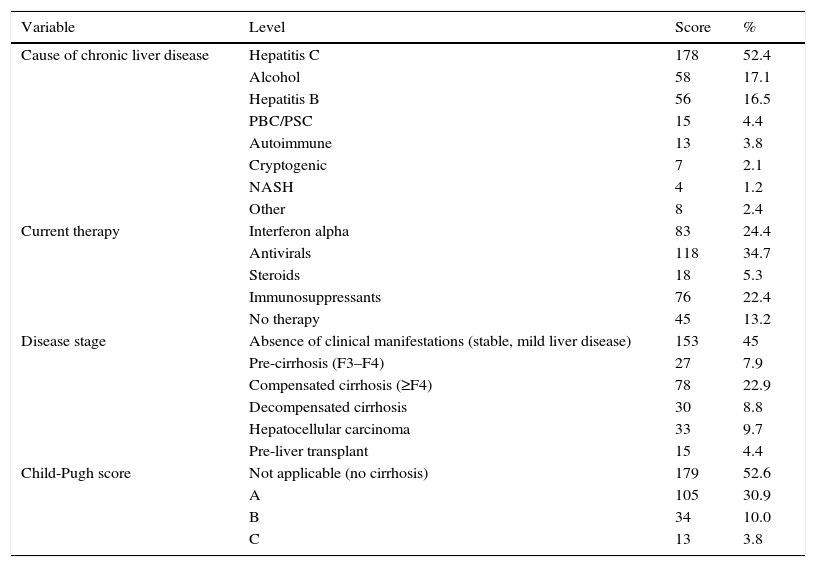

Clinical characteristics of patients (n=340).

| Variable | Level | Score | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of chronic liver disease | Hepatitis C | 178 | 52.4 |

| Alcohol | 58 | 17.1 | |

| Hepatitis B | 56 | 16.5 | |

| PBC/PSC | 15 | 4.4 | |

| Autoimmune | 13 | 3.8 | |

| Cryptogenic | 7 | 2.1 | |

| NASH | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Other | 8 | 2.4 | |

| Current therapy | Interferon alpha | 83 | 24.4 |

| Antivirals | 118 | 34.7 | |

| Steroids | 18 | 5.3 | |

| Immunosuppressants | 76 | 22.4 | |

| No therapy | 45 | 13.2 | |

| Disease stage | Absence of clinical manifestations (stable, mild liver disease) | 153 | 45 |

| Pre-cirrhosis (F3–F4) | 27 | 7.9 | |

| Compensated cirrhosis (≥F4) | 78 | 22.9 | |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 30 | 8.8 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 33 | 9.7 | |

| Pre-liver transplant | 15 | 4.4 | |

| Child-Pugh score | Not applicable (no cirrhosis) | 179 | 52.6 |

| A | 105 | 30.9 | |

| B | 34 | 10.0 | |

| C | 13 | 3.8 |

F3–F4: advanced fibrosis; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis; NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

The questionnaire was administered in person by a health psychologist during the patient's visit to a primary care centre. The aims of the study were explained to patients attending an appointment with a hepatologist, and those who could read and understand the questionnaire and were willing to sign the informed consent form were invited to take part in the study. Patients who could read and understand the questions completed the questionnaire by themselves; those who could not (4.4%) were helped by the psychologist, who read the questions to them.

Seventy two (21.2%) patients completed the questionnaire again within 6 months of their first visit, thus allowing us to conduct a prospective quality of life evaluation. All patients were interviewed between September 2011 and December 2013, and the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital de Bellvitge.

QuestionnairesThree questionnaires were administered in this study. The first consisted of sociodemographic items: personal details, clinical details of the liver disease, awareness of their diagnosis, Child-Pugh class, toxic habits, comorbidities and usual therapy. The patient's answers were later corroborated by their attending doctor. The second questionnaire administered was the SF-36, a generic instrument commonly used worldwide for evaluating HRQOL. The SF-36 is divided into 8 domains: physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, role-physical, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health, and provides a quantitative assessment (score). The third questionnaire contained the 36 items specific to chronic liver disease and liver transplant from the SF-LDQOL, grouped into 9 domains: disease-related symptoms, disease-related effects on activities of daily living, memory/concentration, distress, sleep, loneliness, hopelessness, stigma of the disease, and sexual functioning.

The scores obtained from these domains are converted to a 0–100 scale to facilitate interpretation: the higher the score, the better the HRQOL in each domain. As in the English version of the SF-LDQOL developed by Kanwal et al., 2 additional patient-perceived items were included: severity of symptoms, and incapacity days.

Clinical definitionsPatients with cirrhosis were classified, when possible, according to the 3 levels of severity of the Child-Pugh system: A, B or C. The Child-Pugh score is based on the presence of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, serum bilirubin and albumin, and prothrombin time.

Statistical analysisThe psychometric properties of the questionnaire for the study population were evaluated using the following parameters:

- -

Feasibility: the degree to which a test can be understood and answered by target patients. It was calculated on the basis of the percentage of answers missing in each domain.

- -

Internal consistency: the extent to which items correlate with each other, and are answered in a similar fashion. This was calculated using Cronbach's alpha (reliability) coefficient.

- -

Convergent/discriminant validity: the extent to which a particular domain includes items that correlate with each other and with the domain, and rejects items that correlate more frequently with other domains. For this purpose, a Pearson correlation coefficient between each item and its corresponding domain was calculated.

- -

Scaling: the extent to which each item is assigned to the domain to which it should belong, in the opinion of the investigator. In this case, the original distribution of the English questionnaire was respected. The parameter was calculated on the basis of the percentage of items that correlated more highly (using Pearson's coefficient) with their domain than with other domains.

- -

Construct validity: represents the degree to which the results of a test correlate to a particular domain or construct (in this study: the degree to which the SF-LDQOL scores effectively describe HRQOL of patients with chronic liver disease). It was estimated by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient between items in the SF-36 and specific chronic liver disease-related items. The same was done between specific chronic liver disease-related items and the additional items “severity of symptoms” and “incapacity days”.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v. 19.0.

ResultsPatient characteristicsA total of 340 patients were included, 63.5% were men, mean age was 59.5 years (standard deviation: 11.9). The most common aetiologies were: hepatitis C (52.4%), alcoholic liver disease (17.1%) and hepatitis B (16.5%). Clinical manifestations were absent in 45% of patients; 39.6% presented advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis (decompensated in some cases); and 9.1% had developed hepatocellular carcinoma. Of the total, 21.8% had received at least 1 liver transplant, and 4.4% were on the waiting list for liver transplantation.

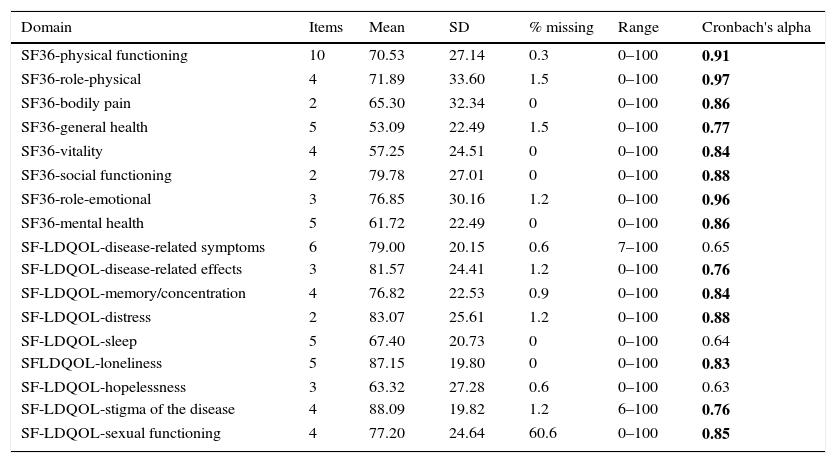

Results of the Short form-36 and Short Form-Liver Disease Quality of Life questionnairesThe distribution of scores and internal consistency of the SF-LDQOL are shown in Table 3. The Cronbach's alpha was over 0.70 in 6 of the 9 specific domains of the SF-LDQOL. The only domains below this score were “disease-related symptoms” (0.65), “sleep” (0.64), and “hopelessness” (0.63). The percentage of missing scores in all domains was below 1.5%, except for sexual functioning, in which over 60% of scores were missing.

Distribution of scores from SF-36 and SF-LDQOL, and internal consistency of domains.

| Domain | Items | Mean | SD | % missing | Range | Cronbach's alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF36-physical functioning | 10 | 70.53 | 27.14 | 0.3 | 0–100 | 0.91 |

| SF36-role-physical | 4 | 71.89 | 33.60 | 1.5 | 0–100 | 0.97 |

| SF36-bodily pain | 2 | 65.30 | 32.34 | 0 | 0–100 | 0.86 |

| SF36-general health | 5 | 53.09 | 22.49 | 1.5 | 0–100 | 0.77 |

| SF36-vitality | 4 | 57.25 | 24.51 | 0 | 0–100 | 0.84 |

| SF36-social functioning | 2 | 79.78 | 27.01 | 0 | 0–100 | 0.88 |

| SF36-role-emotional | 3 | 76.85 | 30.16 | 1.2 | 0–100 | 0.96 |

| SF36-mental health | 5 | 61.72 | 22.49 | 0 | 0–100 | 0.86 |

| SF-LDQOL-disease-related symptoms | 6 | 79.00 | 20.15 | 0.6 | 7–100 | 0.65 |

| SF-LDQOL-disease-related effects | 3 | 81.57 | 24.41 | 1.2 | 0–100 | 0.76 |

| SF-LDQOL-memory/concentration | 4 | 76.82 | 22.53 | 0.9 | 0–100 | 0.84 |

| SF-LDQOL-distress | 2 | 83.07 | 25.61 | 1.2 | 0–100 | 0.88 |

| SF-LDQOL-sleep | 5 | 67.40 | 20.73 | 0 | 0–100 | 0.64 |

| SFLDQOL-loneliness | 5 | 87.15 | 19.80 | 0 | 0–100 | 0.83 |

| SF-LDQOL-hopelessness | 3 | 63.32 | 27.28 | 0.6 | 0–100 | 0.63 |

| SF-LDQOL-stigma of the disease | 4 | 88.09 | 19.82 | 1.2 | 6–100 | 0.76 |

| SF-LDQOL-sexual functioning | 4 | 77.20 | 24.64 | 60.6 | 0–100 | 0.85 |

SD: standard deviation.

Numbers in bold indicate Cronbach's α coefficients above the 0.70 threshold.

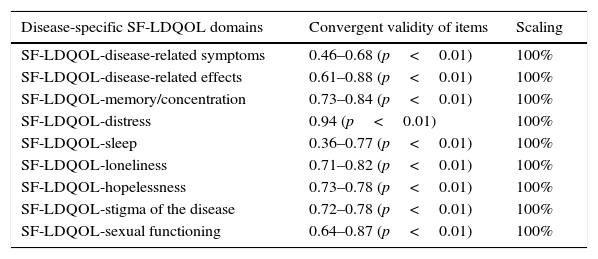

Table 4 shows the results of the convergent validity and scaling analysis. In the SF-LDQOL, item-domain correlation was over 0.4 in all cases, except for “sleep” (0.36–0.77). All scores were statistically significant (p<0.01). Scaling was 100% in all domains.

Convergent validity of domains and scaling.

| Disease-specific SF-LDQOL domains | Convergent validity of items | Scaling |

|---|---|---|

| SF-LDQOL-disease-related symptoms | 0.46–0.68 (p<0.01) | 100% |

| SF-LDQOL-disease-related effects | 0.61–0.88 (p<0.01) | 100% |

| SF-LDQOL-memory/concentration | 0.73–0.84 (p<0.01) | 100% |

| SF-LDQOL-distress | 0.94 (p<0.01) | 100% |

| SF-LDQOL-sleep | 0.36–0.77 (p<0.01) | 100% |

| SF-LDQOL-loneliness | 0.71–0.82 (p<0.01) | 100% |

| SF-LDQOL-hopelessness | 0.73–0.78 (p<0.01) | 100% |

| SF-LDQOL-stigma of the disease | 0.72–0.78 (p<0.01) | 100% |

| SF-LDQOL-sexual functioning | 0.64–0.87 (p<0.01) | 100% |

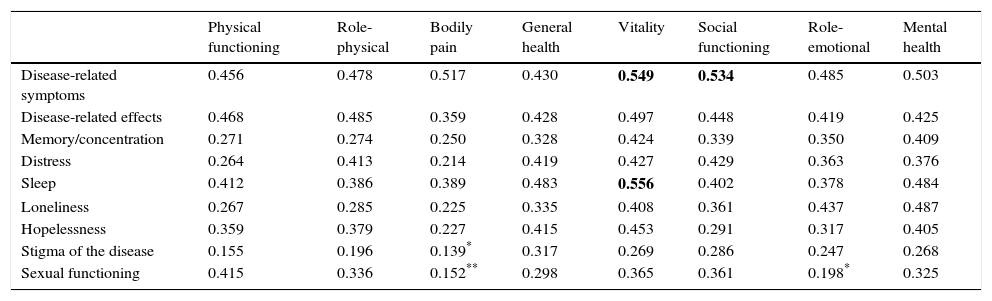

Tables 5 and 6 show the results of the construct validity analysis. Table 5 shows the Pearson correlation coefficient between the SF-36 domains and the liver-specific domains of the SF-LDQOL. Nearly all scores were significant within a range of 0.139 and 0.556. Correlation between SF-36 domains and the 2 additional items were all significant (p<0.01) and negative, showing that the quality of life score was higher when symptoms were less severe and resulted in fewer incapacity days.

Pearson correlation coefficient between SF-36 domains and disease-specific SF-LDQOL domains.

| Physical functioning | Role-physical | Bodily pain | General health | Vitality | Social functioning | Role-emotional | Mental health | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease-related symptoms | 0.456 | 0.478 | 0.517 | 0.430 | 0.549 | 0.534 | 0.485 | 0.503 |

| Disease-related effects | 0.468 | 0.485 | 0.359 | 0.428 | 0.497 | 0.448 | 0.419 | 0.425 |

| Memory/concentration | 0.271 | 0.274 | 0.250 | 0.328 | 0.424 | 0.339 | 0.350 | 0.409 |

| Distress | 0.264 | 0.413 | 0.214 | 0.419 | 0.427 | 0.429 | 0.363 | 0.376 |

| Sleep | 0.412 | 0.386 | 0.389 | 0.483 | 0.556 | 0.402 | 0.378 | 0.484 |

| Loneliness | 0.267 | 0.285 | 0.225 | 0.335 | 0.408 | 0.361 | 0.437 | 0.487 |

| Hopelessness | 0.359 | 0.379 | 0.227 | 0.415 | 0.453 | 0.291 | 0.317 | 0.405 |

| Stigma of the disease | 0.155 | 0.196 | 0.139* | 0.317 | 0.269 | 0.286 | 0.247 | 0.268 |

| Sexual functioning | 0.415 | 0.336 | 0.152** | 0.298 | 0.365 | 0.361 | 0.198* | 0.325 |

All coefficients were statistically significant (p<0.01), except:

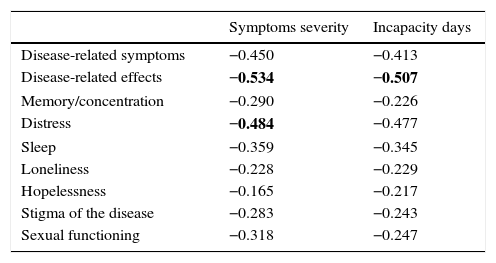

Pearson correlation coefficients between disease-specific domains of the SF-LDQOL and additional variables: symptom severity and incapacity days.

| Symptoms severity | Incapacity days | |

|---|---|---|

| Disease-related symptoms | −0.450 | −0.413 |

| Disease-related effects | −0.534 | −0.507 |

| Memory/concentration | −0.290 | −0.226 |

| Distress | −0.484 | −0.477 |

| Sleep | −0.359 | −0.345 |

| Loneliness | −0.228 | −0.229 |

| Hopelessness | −0.165 | −0.217 |

| Stigma of the disease | −0.283 | −0.243 |

| Sexual functioning | −0.318 | −0.247 |

All coefficients were statistically significant (p<0.01).

Numbers in bold indicate the 3 highest correlation coefficients.

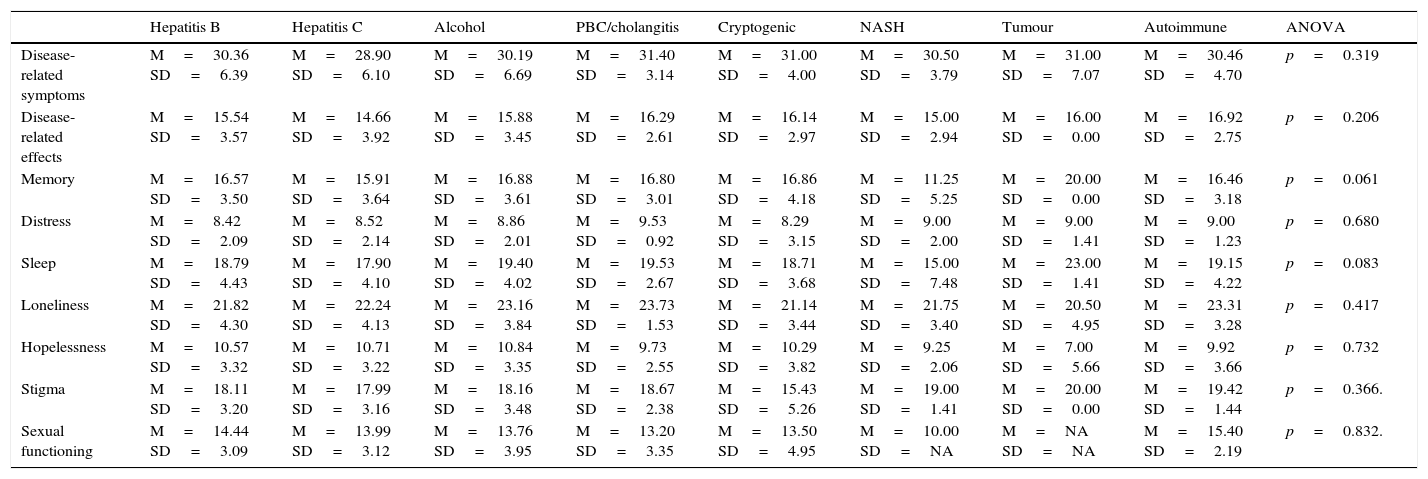

After testing the psychometric properties of the questionnaires, and considering the sample size to be sufficient to obtain more results, we compared the HRQOL scores (exclusively from the specific domains of the SF-LDQOL) with a number of variables that could potentially cause differences. Table 7 shows that the aetiology of the disease (hepatitis C, alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis B, etc.) does not affect patient-perceived quality of life.

Comparison between disease-specific SF-LDQOL domain means and disease aetiology.

| Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | Alcohol | PBC/cholangitis | Cryptogenic | NASH | Tumour | Autoimmune | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease-related symptoms | M=30.36 SD=6.39 | M=28.90 SD=6.10 | M=30.19 SD=6.69 | M=31.40 SD=3.14 | M=31.00 SD=4.00 | M=30.50 SD=3.79 | M=31.00 SD=7.07 | M=30.46 SD=4.70 | p=0.319 |

| Disease-related effects | M=15.54 SD=3.57 | M=14.66 SD=3.92 | M=15.88 SD=3.45 | M=16.29 SD=2.61 | M=16.14 SD=2.97 | M=15.00 SD=2.94 | M=16.00 SD=0.00 | M=16.92 SD=2.75 | p=0.206 |

| Memory | M=16.57 SD=3.50 | M=15.91 SD=3.64 | M=16.88 SD=3.61 | M=16.80 SD=3.01 | M=16.86 SD=4.18 | M=11.25 SD=5.25 | M=20.00 SD=0.00 | M=16.46 SD=3.18 | p=0.061 |

| Distress | M=8.42 SD=2.09 | M=8.52 SD=2.14 | M=8.86 SD=2.01 | M=9.53 SD=0.92 | M=8.29 SD=3.15 | M=9.00 SD=2.00 | M=9.00 SD=1.41 | M=9.00 SD=1.23 | p=0.680 |

| Sleep | M=18.79 SD=4.43 | M=17.90 SD=4.10 | M=19.40 SD=4.02 | M=19.53 SD=2.67 | M=18.71 SD=3.68 | M=15.00 SD=7.48 | M=23.00 SD=1.41 | M=19.15 SD=4.22 | p=0.083 |

| Loneliness | M=21.82 SD=4.30 | M=22.24 SD=4.13 | M=23.16 SD=3.84 | M=23.73 SD=1.53 | M=21.14 SD=3.44 | M=21.75 SD=3.40 | M=20.50 SD=4.95 | M=23.31 SD=3.28 | p=0.417 |

| Hopelessness | M=10.57 SD=3.32 | M=10.71 SD=3.22 | M=10.84 SD=3.35 | M=9.73 SD=2.55 | M=10.29 SD=3.82 | M=9.25 SD=2.06 | M=7.00 SD=5.66 | M=9.92 SD=3.66 | p=0.732 |

| Stigma | M=18.11 SD=3.20 | M=17.99 SD=3.16 | M=18.16 SD=3.48 | M=18.67 SD=2.38 | M=15.43 SD=5.26 | M=19.00 SD=1.41 | M=20.00 SD=0.00 | M=19.42 SD=1.44 | p=0.366. |

| Sexual functioning | M=14.44 SD=3.09 | M=13.99 SD=3.12 | M=13.76 SD=3.95 | M=13.20 SD=3.35 | M=13.50 SD=4.95 | M=10.00 SD=NA | M=NA SD=NA | M=15.40 SD=2.19 | p=0.832. |

M: mean; NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; SD: standard deviation.

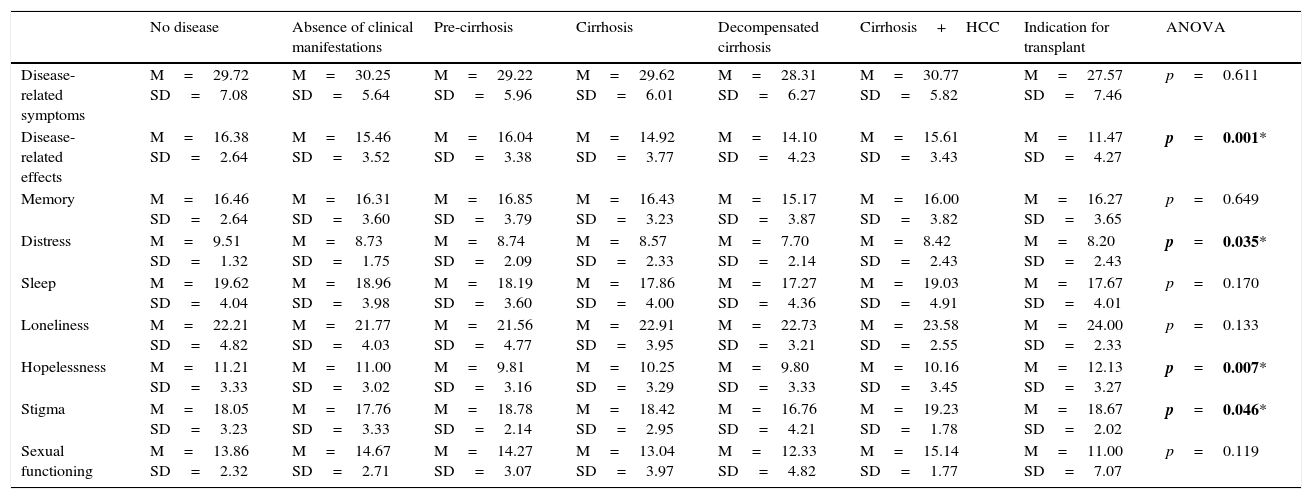

However, differences in HRQOL were found when patients were compared according to the stage of liver disease. These differences were found in in several domains: “disease-related effects” (HRQOL score was lower when patients were on a waiting list for a liver transplantation); “distress” (the lowest scores were obtained from patients with decompensated cirrhosis); “hopelessness” (significantly lower scores in patients diagnosed with liver cancer); and “stigma of the disease” (scored lowest by liver transplant candidates). The full results are shown in Table 8.

Comparison between disease-specific SF-LDQOL domain means and disease stage.

| No disease | Absence of clinical manifestations | Pre-cirrhosis | Cirrhosis | Decompensated cirrhosis | Cirrhosis+HCC | Indication for transplant | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease-related symptoms | M=29.72 SD=7.08 | M=30.25 SD=5.64 | M=29.22 SD=5.96 | M=29.62 SD=6.01 | M=28.31 SD=6.27 | M=30.77 SD=5.82 | M=27.57 SD=7.46 | p=0.611 |

| Disease-related effects | M=16.38 SD=2.64 | M=15.46 SD=3.52 | M=16.04 SD=3.38 | M=14.92 SD=3.77 | M=14.10 SD=4.23 | M=15.61 SD=3.43 | M=11.47 SD=4.27 | p=0.001* |

| Memory | M=16.46 SD=2.64 | M=16.31 SD=3.60 | M=16.85 SD=3.79 | M=16.43 SD=3.23 | M=15.17 SD=3.87 | M=16.00 SD=3.82 | M=16.27 SD=3.65 | p=0.649 |

| Distress | M=9.51 SD=1.32 | M=8.73 SD=1.75 | M=8.74 SD=2.09 | M=8.57 SD=2.33 | M=7.70 SD=2.14 | M=8.42 SD=2.43 | M=8.20 SD=2.43 | p=0.035* |

| Sleep | M=19.62 SD=4.04 | M=18.96 SD=3.98 | M=18.19 SD=3.60 | M=17.86 SD=4.00 | M=17.27 SD=4.36 | M=19.03 SD=4.91 | M=17.67 SD=4.01 | p=0.170 |

| Loneliness | M=22.21 SD=4.82 | M=21.77 SD=4.03 | M=21.56 SD=4.77 | M=22.91 SD=3.95 | M=22.73 SD=3.21 | M=23.58 SD=2.55 | M=24.00 SD=2.33 | p=0.133 |

| Hopelessness | M=11.21 SD=3.33 | M=11.00 SD=3.02 | M=9.81 SD=3.16 | M=10.25 SD=3.29 | M=9.80 SD=3.33 | M=10.16 SD=3.45 | M=12.13 SD=3.27 | p=0.007* |

| Stigma | M=18.05 SD=3.23 | M=17.76 SD=3.33 | M=18.78 SD=2.14 | M=18.42 SD=2.95 | M=16.76 SD=4.21 | M=19.23 SD=1.78 | M=18.67 SD=2.02 | p=0.046* |

| Sexual functioning | M=13.86 SD=2.32 | M=14.67 SD=2.71 | M=14.27 SD=3.07 | M=13.04 SD=3.97 | M=12.33 SD=4.82 | M=15.14 SD=1.77 | M=11.00 SD=7.07 | p=0.119 |

SD: standard deviation; HCC: hepatocarcinoma; M: mean.

Numbers in bold with an asterisk indicate statistically significant differences (p≤0.05).

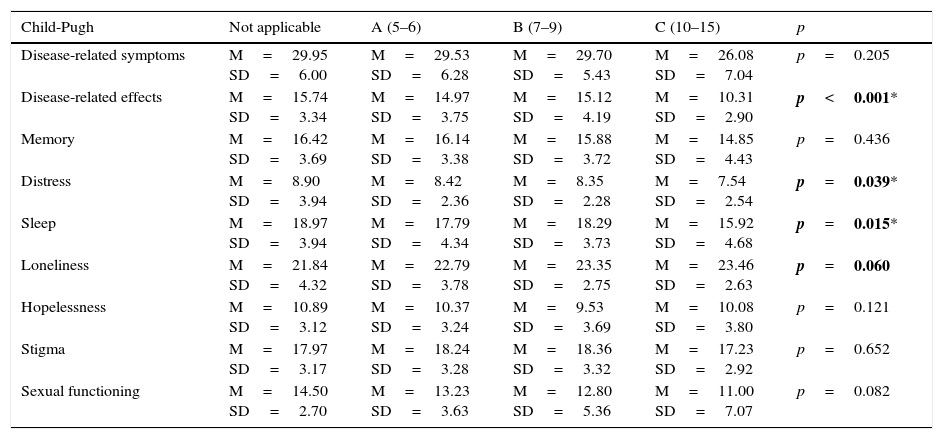

The Child-Pugh status also affects the score in disease-specific quality of life domains. The results are shown in Table 9. Statistically significant differences were found in 3 domains: “disease-related effects”, “distress” and “sleep”. These domains scored lowest in patients with more advanced liver failure.

Comparison between disease-specific SF-LDQOL domain means and Child-Pugh class.

| Child-Pugh | Not applicable | A (5–6) | B (7–9) | C (10–15) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease-related symptoms | M=29.95 SD=6.00 | M=29.53 SD=6.28 | M=29.70 SD=5.43 | M=26.08 SD=7.04 | p=0.205 |

| Disease-related effects | M=15.74 SD=3.34 | M=14.97 SD=3.75 | M=15.12 SD=4.19 | M=10.31 SD=2.90 | p<0.001* |

| Memory | M=16.42 SD=3.69 | M=16.14 SD=3.38 | M=15.88 SD=3.72 | M=14.85 SD=4.43 | p=0.436 |

| Distress | M=8.90 SD=3.94 | M=8.42 SD=2.36 | M=8.35 SD=2.28 | M=7.54 SD=2.54 | p=0.039* |

| Sleep | M=18.97 SD=3.94 | M=17.79 SD=4.34 | M=18.29 SD=3.73 | M=15.92 SD=4.68 | p=0.015* |

| Loneliness | M=21.84 SD=4.32 | M=22.79 SD=3.78 | M=23.35 SD=2.75 | M=23.46 SD=2.63 | p=0.060 |

| Hopelessness | M=10.89 SD=3.12 | M=10.37 SD=3.24 | M=9.53 SD=3.69 | M=10.08 SD=3.80 | p=0.121 |

| Stigma | M=17.97 SD=3.17 | M=18.24 SD=3.28 | M=18.36 SD=3.32 | M=17.23 SD=2.92 | p=0.652 |

| Sexual functioning | M=14.50 SD=2.70 | M=13.23 SD=3.63 | M=12.80 SD=5.36 | M=11.00 SD=7.07 | p=0.082 |

M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

No statistically significant differences were found between HRQOL and age. In terms of level of education, the only statistically significant difference (p=0.014) was found in the “hopelessness” domain, in which the higher the level of education, the higher the score, i.e., less feeling of hopelessness.

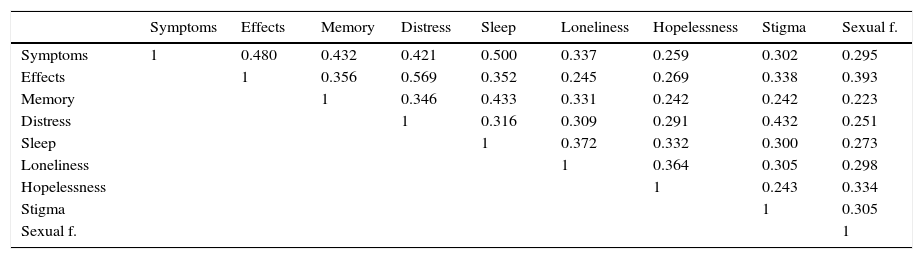

The disease-specific domains of the SF-LDQOL were also intercorrelated, as was the case in Kanwal's original English version. This can be seen in Table 10, which shows the Pearson correlation coefficient between these variables.

Pearson correlation coefficient between disease-specific SF-LDQOL domains.

| Symptoms | Effects | Memory | Distress | Sleep | Loneliness | Hopelessness | Stigma | Sexual f. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | 1 | 0.480 | 0.432 | 0.421 | 0.500 | 0.337 | 0.259 | 0.302 | 0.295 |

| Effects | 1 | 0.356 | 0.569 | 0.352 | 0.245 | 0.269 | 0.338 | 0.393 | |

| Memory | 1 | 0.346 | 0.433 | 0.331 | 0.242 | 0.242 | 0.223 | ||

| Distress | 1 | 0.316 | 0.309 | 0.291 | 0.432 | 0.251 | |||

| Sleep | 1 | 0.372 | 0.332 | 0.300 | 0.273 | ||||

| Loneliness | 1 | 0.364 | 0.305 | 0.298 | |||||

| Hopelessness | 1 | 0.243 | 0.334 | ||||||

| Stigma | 1 | 0.305 | |||||||

| Sexual f. | 1 |

All coefficients are significant (p≤0.01).

The validation of the Spanish version of the SF-LDQOL provides clinicians with a useful tool that takes less time to administer than its predecessor (LDQOL), thus reducing patient fatigue and the time needed to complete the questionnaire.

The specific SF-LDQOL questionnaire has been validated in a group of outpatients seen in a tertiary hospital with a liver transplant programme.

This study is the first to validate the Spanish version of the SF-LDQOL, and can be used to assess the quality of life of patients with liver disease of different aetiology and severity. It is important to bear in mind that liver disease is asymptomatic over much of its evolution, and that analytical tests and imaging studies do not explain all the symptoms. In recent years, more effective and safer treatments have been introduced, and it is of paramount importance to assess the HRQOL of this patient group. Identifying which quality of life domains are affected in each patient will indicate the best strategies for improving their situation.

The results obtained in this study show that the questionnaire can be used in all stages of chronic liver disease, even in patients with advanced liver failure, and that our study sample differs slightly from that of other studies. Patients with advanced disease have the greatest difficulty in answering all the items in the questionnaire, although they are precisely the population that would most benefit from steps taken to improve their quality of life.

In our sample, we included a wide range of clinical severity profiles, as our objective was to validate a questionnaire that can be used at all stages of the disease. This gives our study two important advantages: it improves the psychometric quality of the test, and it allows clinicians to monitor quality of life as the disease worsens.

The aetiologies of liver disease found in this series are similar to those found in other Mediterranean populations. The main cause is hepatitis C infection, with most patients having been infected for more than 10 years (becoming infected before 1990). However, when comparing our findings with those of other studies, such as the North American series used by Kanwal in her original validation of the SF-LDQOL, some differences come to light: both the mean age (59.5 years vs 53.9 years) and also the proportion of males (63.5% vs 54.8%) in our sample are higher. This would also explain why our sample includes more retired patients (40%) than Kanwal's study (21%). The studies also differ in level of education: in Kanwal's, the proportion of subjects with university education was 48.6%, compared to only 11.5% in our series. Additionally, Kanwal's population included fewer patients with hepatitis B and C infection.

The scores obtained in each domain also differs significantly between the original version validated by Kanwal and our Spanish version of the questionnaire: in our study scores were generally 20 points higher in each domain. This is true of both the SF-36 domain and the disease-specific domains of the SF-LDQOL, with a single exception in the “hopelessness” domain, where the score was higher in the US version. This could be due to various factors, including the wider range of treatments and medical consultations included in the Spanish Public Health System, sociocultural differences, and differences between the American and Mediterranean lifestyle.

The psychometric properties of both questionnaires (wherever a comparison could be made) are similar overall.

Analysing the results of the evaluation of the psychometric properties of the questionnaire shows the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of 6 of the specific disease-related domains of the SF-LDQOL to be higher than the threshold of 0.70. The only domains that failed to reach this were “disease-related symptoms”: 0.65; “sleep”: 0.64; and “hopelessness”: 0.63. This shows that the domains are consistent, i.e., that the grouping of items in each domain is coherent. The 3 domains that did not reach the threshold failed to do so by a small margin. We believe this could be due to the following:

- (a)

The “disease-related symptoms” domain includes a wide range of clinical pictures, and a high prevalence of asymptomatic patients. The measurement window for this item is 1 week; therefore, a higher or lower score will depend on when the questionnaire was administered.

- (b)

Problems with sleep patterns are common in the general adult population, but are accentuated in patients with chronic liver disease. Lack of consistency in the “sleep” domain could be due to the fact that what it really measures are different aspects of sleep that are not necessarily complementary: the “amount” of sleep and daytime wakefulness (a patient can be more or less sleepy during the day, irrespective of whether or not they slept well during the night). In patients with advanced disease, changes in sleep patterns can also be explained by hepatic encephalopathy.

- (c)

In the case of “hopelessness”, the threshold may have been low because patients might be able to envisage making plans for the future, even in the knowledge that these are unlikely to be fulfilled. Again, therefore, this domain measures two similar, but not identical, aspects: the patient's desire for a particular future, and their belief in how their future will really be.

Overall, few items were left unscored, indicating that patients had sufficient time to complete the questionnaire: items were relevant to the patients, and they were able to answer without becoming fatigued. The only domain with a high percentage (60.6%) of unscored items was “sexual functioning”. This could be due to an item on this domain (“16. Have you had sexual intercourse in the past 4 weeks?”) where answering “no” invalidated the following 3 questions, which were therefore left unscored. In many cases, the psychologists detected a certain lack of interest among patients in this aspect of their quality of life (i.e., a return to an active sex life was not a priority among patients).

The scaling and convergent/discriminant validity of the domains of the SF-LDQOL questionnaire was tested on the basis of distribution of items in Kanwal's original version, which was maintained in the Spanish version, obtaining an item-domain correlation of over 4.0 in all items except for “naps” in the “sleep” domain, which had a correlation of 0.36. In our opinion, this could be due to cultural differences with regard to daytime naps. It is important to note that a large proportion of our subjects were retired, and many had severe disease, both factors that could have increased daytime sleepiness. Scaling was 100% in all cases: all items correlated more strongly with their domain than with any other.

A high correlation was also observed between the additional items “severity of symptoms” and “incapacity days” and the remaining elements in the questionnaire. These correlations were statistically significant in all cases. In the case of these symptoms, the higher the score, the worse the quality of life. However, in the SF-LDQOL domain the opposite is true (the higher the score, the better the HRQOL). Therefore, the former correlations are negative.

Scores recorded for the disease-specific domains of the SF-LDQOL did not differ in accordance with the aetiology of the disease in this series.

However, as would be expected, there were differences in HRQOL at different stages of liver disease. This confirms the hypothesis that the more advanced the disease, the worse the patient's quality of life. This led to significant differences in the “disease-related effects on activities of daily living”, “distress”, “hopelessness” and “stigma of the disease” domains, with the worst scores in these subdomains coming from liver transplant candidates. This corresponds with patients with objectively more severe disease, but is also due to the patient's presence on a transplant waiting list, and the uncertainty of whether a donor will be found in time. It unclear whether patient-perceived feelings of well-being are related with the developmental stage of the disease, as it is influenced by circumstances such as access to treatment and aetiology.

As liver disease is characterised by a slow evolution, the most severe stages of the disease are generally found in older patients. The correlation between age on the one hand and distress or hopelessness on the other could depend on 2 factors: first, physical health deteriorates with age; and secondly, impaired physical health could increase feelings of anxiety and depression, particularly in women. This mechanism has been observed in other studies.

In this series, as in previous studies in other populations, men reported fewer health problems than women. These findings must be interpreted in the context of deeply rooted social and cultural attitudes, and can only be clarified with further research.

Liver transplant recipients reported significant improvement in 3 domains: “disease-related effects on activities of daily living”, “memory/concentration”, and “distress”. Improvements in these aspects following liver transplantation have also been reported by other authors, such as De Bona21 and Karam.22

Disease-specific domains showed statistically significant correlations in all combinations. This is an important finding, as it suggests that improvement in 1 HRQOL parameter could have a “knock on” effect on other parameters.

The 72 patients included in the prospective follow-up presented significant changes in scores in some domains, including “distress”, “sleep”, “loneliness” “stigma of the disease”, and “sexual functioning”. In these patients, quality of life had deteriorated considerably due to worsening of the disease. This has been correlated clinically, but the data are not shown here. The findings obtained from the domains should form the basis for specific interventions, although further studies are needed. Providing the patient with information regarding their diagnosis and the natural course of their disease could affect their emotional well-being.

ConclusionsThis study has confirmed the psychometric validity of the Spanish version of the short form of the quality of life questionnaire for patients diagnosed with chronic liver disease and liver transplant recipients (SF-LDQOL), making it a useful instrument for both routine clinical practice and research. Patients present similar symptoms, irrespective of the aetiology of their disease, and some differences are observed in accordance with the severity of the disease and the treatment administered.

The SF-LDQOL can be used in future studies to evaluate changes in HRQOL following liver transplantation and other treatments. The questionnaire can be administered at certain times, and can be accompanied by other psychological evaluation instruments. The questionnaire can also be used in conjunction with other prognostic indices to help stratify patients according to the severity of their disease and prognosis. In our opinion, the domains that most accurately predict clinical outcomes, or those in which the score does not improve following treatment or intervention, as well as domains with unscored items, could form the basis for research into the creation of new, complementary questionnaires. We believe that HRQOL evaluation instruments should be based on the needs expressed by the patients themselves. The benefits of such tools has been reported by other authors, such as Doward et al.,23 in relation to other diseases.

FundingThis study has received a grant from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS) of the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Policies and Equality, and the Instituto Carlos III, reference no. 11/00855, jointly funded by the EU's ERDF.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Casanovas Taltavull T, Chandía Frías A, Vilallonga Vilarmau J-S, Peña-Cala MC, de la Iglesia Vicario I, Herdman M. Validación prospectiva de la versión corta en español del test específico de calidad de vida Short form-liver disease quality of life (SF-LDQOL) para hepatopatías crónicas y trasplante hepático. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:243–254.