Glucagonoma is a rare tumour of the alpha cells of the islets of both the body and tail of the pancreas. Approximately 70% are associated with glucagonoma syndrome, characterised by the development of necrolytic migratory erythema (NME), diabetes mellitus, weight loss, anaemia, diarrhoea, neuropsychiatric disorders and thromboembolic phenomena.1 NME is a rare skin condition, involving erythematous, pruritic, painful papules in the perineum and intertriginous areas. The papules group together forming plaques around a central blister. In 90% of cases, NME is associated with a glucagonoma.2 The skin lesions can sometimes adopt a psoriasiform appearance, and the differential diagnosis between psoriasis and NME should be made in the case of widespread psoriasis which does not improve with sustained treatment.

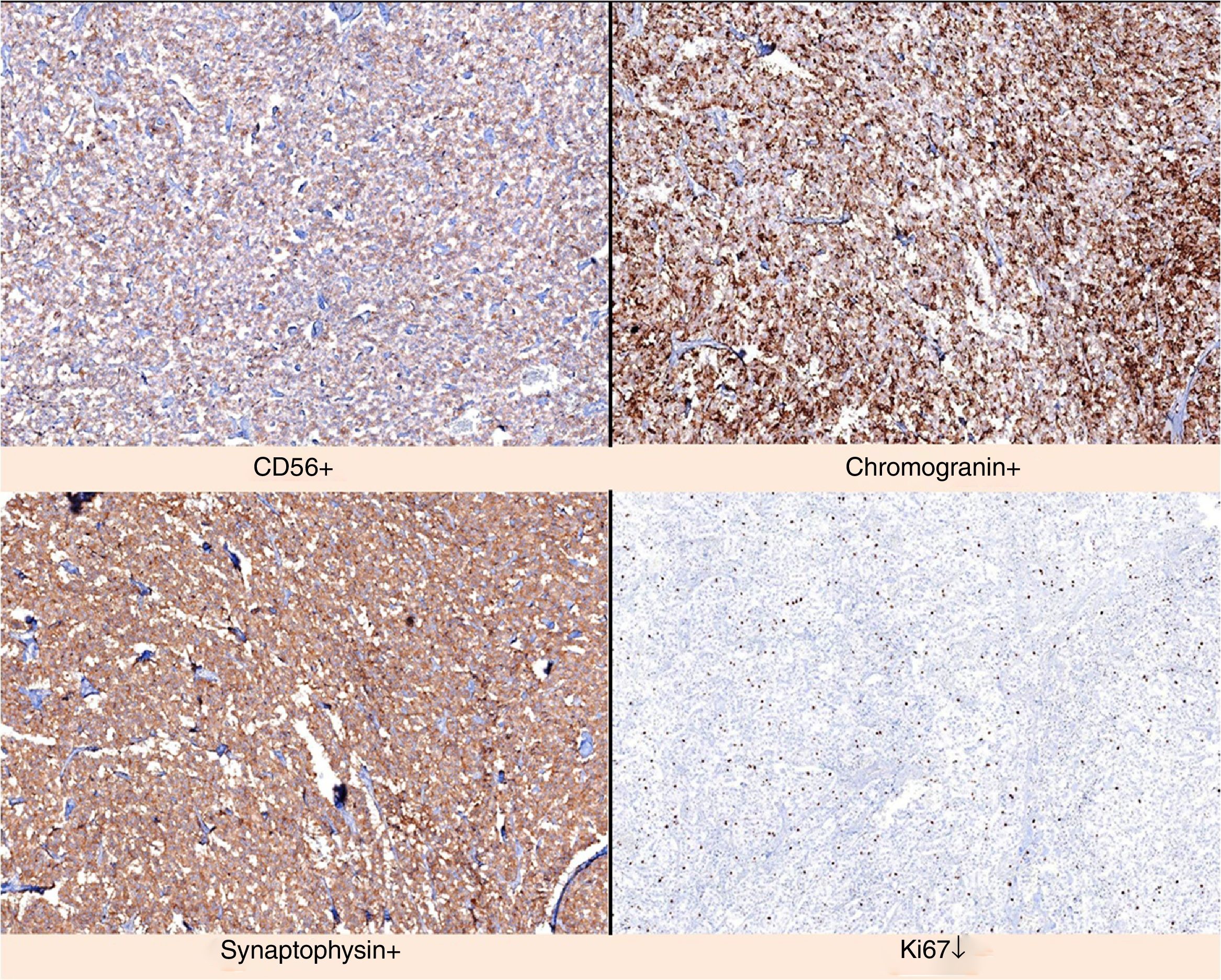

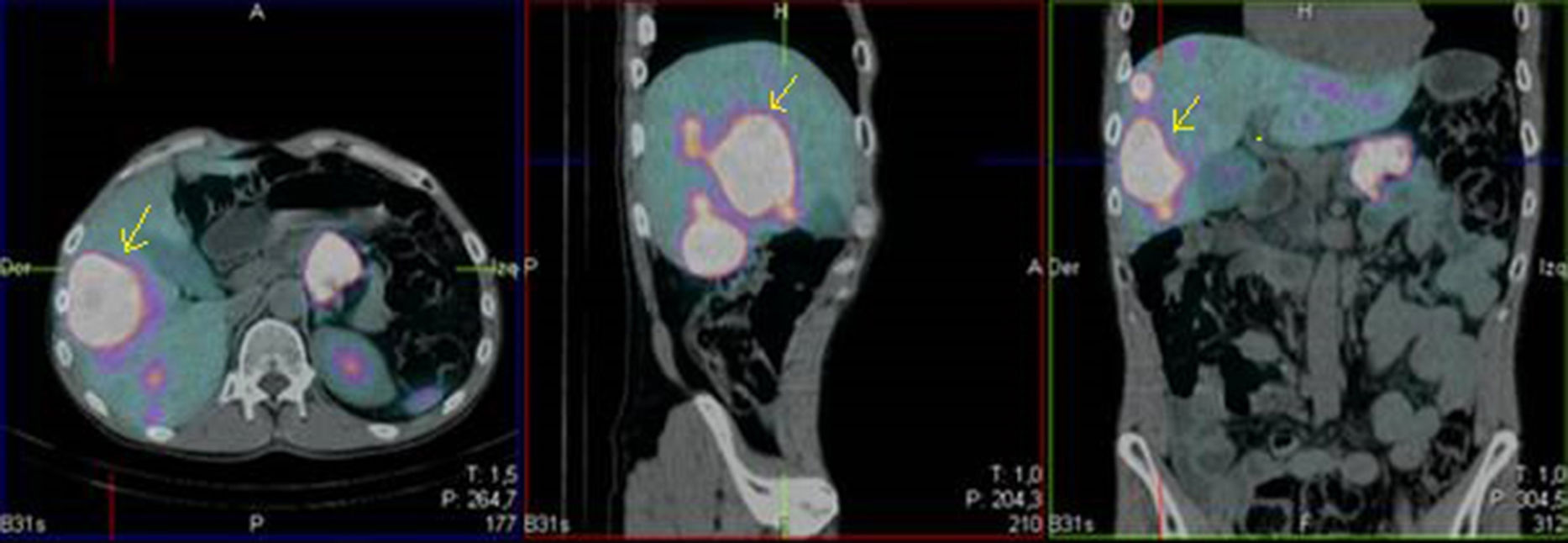

We present the case of a 52-year-old male investigated by dermatology for skin lesions. He was diagnosed with psoriasis vulgaris, but over the course of three years on treatment, without showing any improvement, he developed new lesions consisting of erythematous, erosive-crusted plaques on his lower limbs (particularly below the knees). A skin biopsy was requested as NME was suspected. The analysis showed psoriasiform dermatitis with compact parakeratosis and morphologically consistent subcorneal pustules and the patient was diagnosed with early-stage NME (Figs. 1 and 2). An abdominal CT scan was performed, finding a 3.2-cm mass in the body of the pancreas with lymphadenopathy in the coeliac trunk of a significant size and multiple liver metastases affecting both lobes. Blood tests showed normal blood glucose, haemoglobin 12.3g/dl (13.5–17.5), haematocrit 36% (41–53%), lutropin 12.5mIU/ml (1.5–9.3), follitropin 5.9mIU/ml (1.5–12.4), cortisol 14.3μg/dl (6.2–19.4), somatotropin 1.3ng/ml (<10.0), adrenocorticotropic hormone 87.8pg/ml (<46.0), enolase 29ng/ml (<16.0), beta-hCG 69mIU/ml (<3.0) and carcinoembryonic antigen 1.4ng/ml (<5.0). Investigations were completed with OctreoScan® (Fig. 3), which showed a large mass in the body of the pancreas measuring approximately 3cm, compatible with a glucagonoma, in addition to numerous areas of abnormal uptake of tracer in both lobes of the liver. Glucagonoma was diagnosed, which we decided to treat surgically, performing distal pancreatectomy with lymphadenectomy. The pathology report concluded that it was a well-differentiated G1 neuroendocrine tumour, compatible with glucagonoma of the body of pancreas, pT3 pN1. After surgery, the patient made good progress and, two weeks after the intervention, the skin lesions had completely disappeared (Fig. 4). The patient is currently on treatment with lanreotide and is awaiting assessment for liver transplantation.

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours, of which glucagonoma represents 4%, account for 2% of all gastrointestinal tumours.3 Glucagonoma is more common in females aged over 45. Approximately 50% of the patients diagnosed with these tumours develop clinical signs and symptoms related to the biological activity of the hormones secreted by the cancer. In patients with glucagonoma, 70–80% have the following triad: diabetes, NME and anaemia. Like other neuroendocrine tumours, glucagonomas express somatostatin receptors in more than 80% of cases.

Glucagonomas can be detected by CT, MRI or ultrasound.4 As they express somatostatin receptors, scintigraphy with somatostatin analogues is used to demonstrate the presence of the cancer and the extent to which it may have spread.

These tumours are slow-growing, with a high 10-year survival rate of over 50% in patients with metastasis, and around 65% in those without metastases. Mean survival is from three to seven years after diagnosis.5 The most effective treatment for NME is based on returning the glucagon levels to normal through surgical removal of the pancreatic tumour, as occurred with our patient. Surgical treatment is indicated in patients with disease limited to the pancreas, with or without lymphadenopathy, and for patients with liver or other potentially resectable metastases.6

Over 50% of patients with clinical symptoms have liver metastases at the time of diagnosis. The surgical treatment of single liver metastasis has a 10-year survival rate of 60%. When the patient has liver metastases in both lobes with no extrahepatic disease and the tumour is resectable, liver transplantation with mean five-year survival of 40–81% may be indicated. If surgical treatment of metastases is contraindicated, chemoembolisation or radiofrequency ablation may be performed. Palliative treatment with somatostatin or its analogue (octreotide) achieves good results. These drugs reduce the conversion of proglucagon to glucagon, causing their levels to fall, achieving clinical improvement in many cases. Medical treatment with somatostatin analogues is considered the treatment of choice in cases of unresectable tumour. It also has benefits in the states of hormone overproduction (should be used in cases where the symptoms persist). The choice of treatment has to be made on an individual basis.7

In conclusion, the spread of the tumour and the presence of metastases will determine the curative strategy to follow, with surgery being the technique of choice when the primary disease is under control and liver metastases (if any) are potentially resectable. Aggressive treatment of liver metastases seems to obtain better results in terms of the individual's survival. We believe it is important to stress that in the case of a psoriasiform lesion which does not respond to usual treatment, we should suspect a possible NME secondary to glucagonoma.

Please cite this article as: Martínez Manzano Á, Balsalobre Salmerón MD, García López MA, Soto García S, Vázquez Rojas JL. Lesiones psoriasiformes: forma infrecuente de presentación de glucagonoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:500–502.