Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN) is an umbilical metastasis of any primary tumour.1–4 It can be the first sign of an undiagnosed neoplasm, or can appear as a recurrence or progression of an already known tumour.1,5 We present a new case caused by a gallbladder cancer, and review the topic.

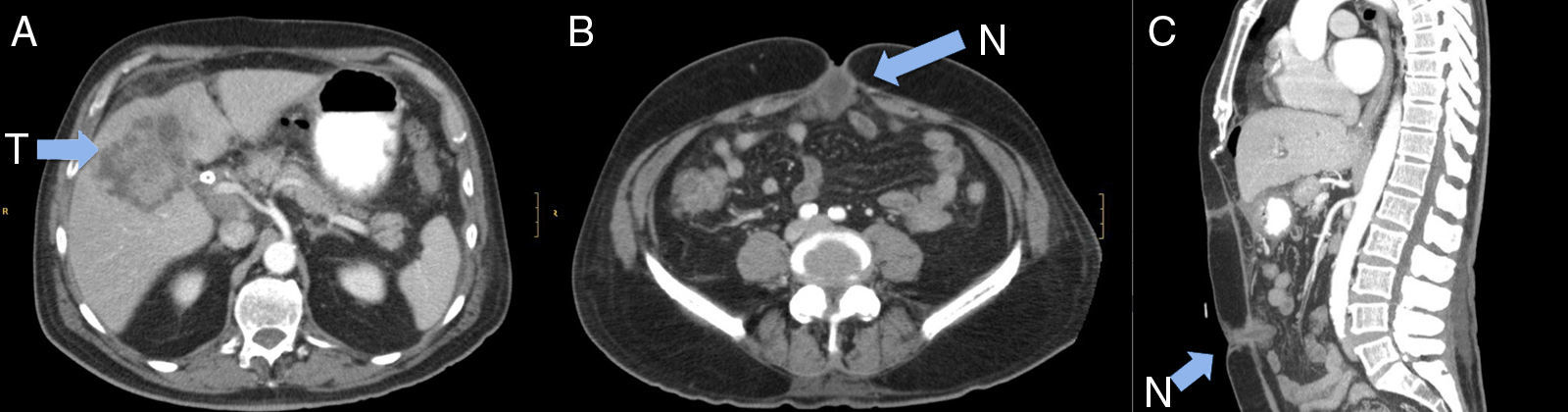

A 76-year-old man presented with a 3-month history of right upper quadrant pain and dyspepsia, accompanied by acholia, choluria and pruritus in the previous 10 days. He reported that he noticed umbilical discomfort that he related with a previous herniorrhaphy. His medical history included atrial fibrillation and umbilical herniorrhaphy. Physical examination found right upper quadrant pain, a petrous tumour in the umbilical region and jaundice. Blood tests revealed gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT): 718IU/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP): 391IU/L, total bilirubin: 9.1; carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): 92.7mg/dL and CA19.9: 206IU/L. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scans showed a large heterogeneous solid lesion with poorly defined borders in the perihilar region, emerging from the fundus of the gallbladder and causing bilateral dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct; the walls of the gallbladder were thickened with increased uptake, and the patient also had numerous gallstones (Fig. 1A). There were multiple lymphadenopathies in the hepatic hilum, some measuring up to 30mm, and an implant in the umbilical region (Fig. 1B and C). Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and external–internal biliary drainage were performed, observing stenosis of the bile duct due to extrinsic compression. Biliary cytology was reported as carcinoma, and fine-needle aspiration of the lesion as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. A biliary stent was placed with resolution of the jaundice, but the patient developed uncontrollable vomiting and complete dietary intolerance. The CT scan was repeated, confirming marked gastric and oesophageal dilatation due to stenosis in the first duodenal portion due to compression of the tumour, which had advanced. Placement of a duodenal stent was attempted but was not possible, so palliative bypass surgery was carried out.

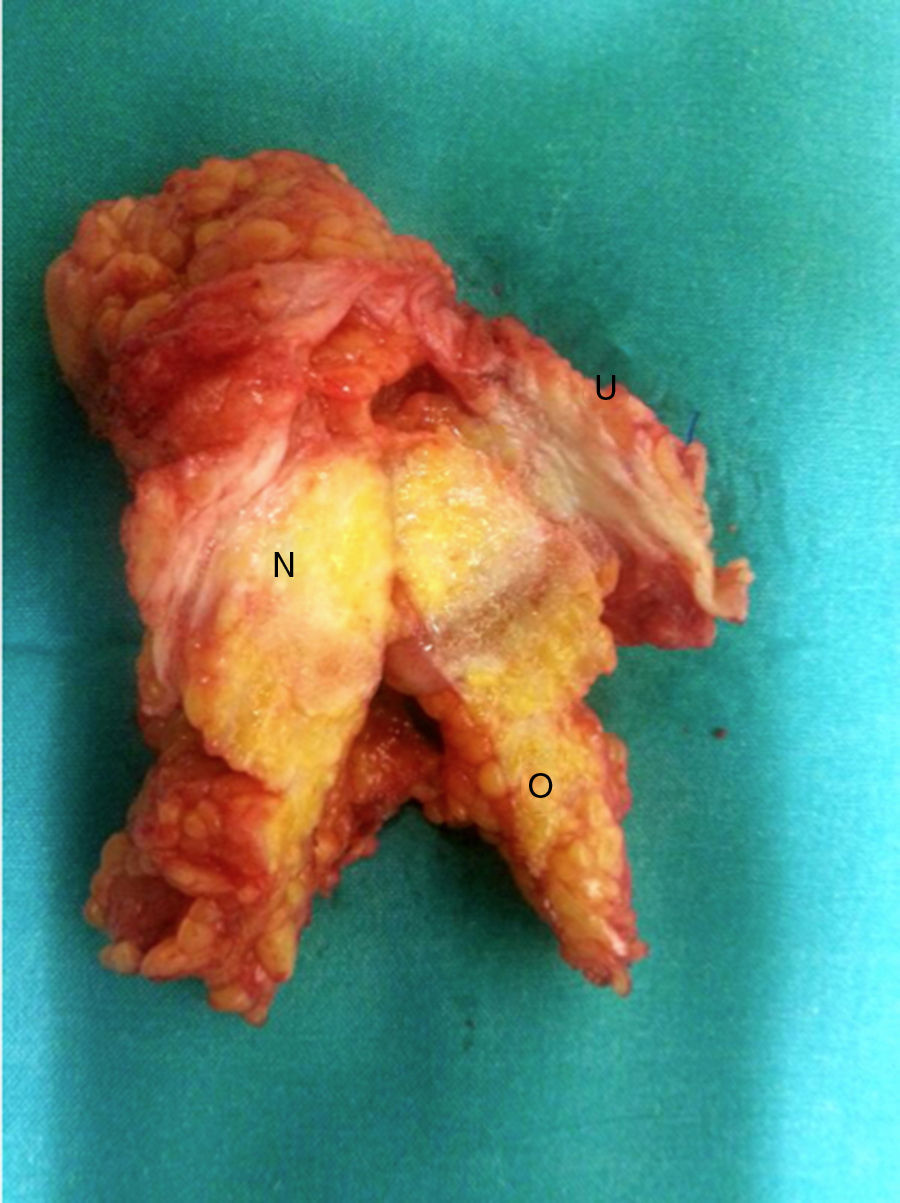

A supra-umbilical midline laparotomy was performed, identifying the following structures: a 5-cm implant that encompassed the umbilical region and greater omentum (Fig. 2); a mass that encompassed liver segments 4b, 5 and 8 and the gallbladder; and peritoneal implants in the pelvis and epiploic foramen. The umbilical implant was resected and two-layer gastrojejunostomy performed in the posterior wall of the stomach. Histological study showed an epithelial tumour composed of neoplastic cells with ample, slightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, an irregular, enlarged vesicular nucleus and a nucleolus, abundant mitoses, and no clear images of lymphovascular invasion. The immunohistochemical study was consistent with biliary adenocarcinoma. The patient died in the postoperative period due to respiratory failure.

Malignant umbilical lesions can be primary or metastatic.6 The first umbilical metastasis was described by Storer in 1864, but the best-known description was published by Dr. W. Mayo in 1928.1 Later, in 1949, British surgeon H. Bailey named it SMJN, in honour of Sister Mary Joseph, nurse and surgical assistant of Dr. Mayo at St. Mary's Hospital in Rochester (MN, USA), as it was she who observed the presence of an umbilical nodule in some patients with advanced gastric cancers.1–10

Although SMJN is said to occur in 1–3% of patients with pelvic and abdominal tumours, the number of cases described in the medical literature is much lower, and it appears to be more common in women.1,4,5,9 It is most often caused by stomach and colon tumours in men, and ovarian tumours in women.1,2 SMJNs have their primary origin in tumours of the gastrointestinal (35–65%) and genitourinary tract (12–35%), unknown origin (15–30%) and other tumours (breast, lung, etc.) (3–6%).1,2,6,8,10 Only 9 cases of SMJN due to gallbladder cancer have been described in PubMed (1966–2015).1,7

The aetiological mechanism of SMJN is not fully understood. In abdominal neoplasms, direct infiltration through the peritoneum—especially if there is peritoneal dissemination as in our case—is the most logical explanation, but this route is not feasible in other tumours. Other mechanisms have therefore been proposed (arterial, venous or lymphatic dissemination or via embryonic structures [urachus]).1,2,4,5,8,9 Liver metastases have been observed in most patients with SMJN, suggesting possible spread via the falciform ligament.1,4

SMJN varies in colour, and can be white, purplish or brownish.1,9 The nodules are typically firm and irregular, located at dermal, subcutaneous or peritoneal level, and measuring 1–2cm, although nodules of up to 10cm have been described; they may be painful and occasionally itchy. They can sometimes ulcerate or fistulise, with a serous, purulent or bloody discharge. If there is an umbilical hernia, or in large lesions, they can infiltrate the gastrointestinal tract, causing bowel obstruction.5

Radiological diagnosis by abdominal ultrasound or CT can be complicated.4,8 The use of positron emission tomography (PET)-CT has been described in 1 patient, with good results.8 Fine-needle aspiration of SMJN is simple, and the cytological study usually obtains a diagnosis of malignancy that enables a correct diagnostic approach, although it may not always define the histological type.1,3 The differential diagnosis of SMJM includes: Paget disease, haemangioma, umbilical hernia, endometriosis, hypertrophic scar, granuloma, pilonidal sinus, dermoid cyst, mycosis, psoriasis, eczema, etc.1,3

SMJN is an ominous sign of metastatic disease.1,3,5,9,10 Mean survival following diagnosis varies between 2 and 11 months, although this is further reduced if it appears as a recurrence after treatment of the primary tumour.1,5,10 Somewhat longer survivals (17–21 months) have been obtained with surgery and chemotherapy.1,4,5 Surgical excision is only recommended if it is a solitary metastasis or causes complications, and is pointless in cases of unresectable disseminated disease.1 The prognosis is related with the primary tumour, with SMJN caused by ovarian cancer having better survival rates.1,4

In conclusion, when a hard umbilical nodule is found, the diagnosis of SMJN should be borne in mind, even if the patient does not have a previous diagnosis of neoplasm. Prognosis is poor, since it appears in patients with disseminated disease. Resection is not generally indicated.

Please cite this article as: Ramia JM, de la Plaza R, López-Marcano A, Kuhnhardt A, David Gonzales J. Nódulo de la hermana María José: metástasis umbilical de cáncer de vesícula. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:302–304.