A 61-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to cholelithiasis without any other medical history. The patient was discharged during the same day with no immediate complications.

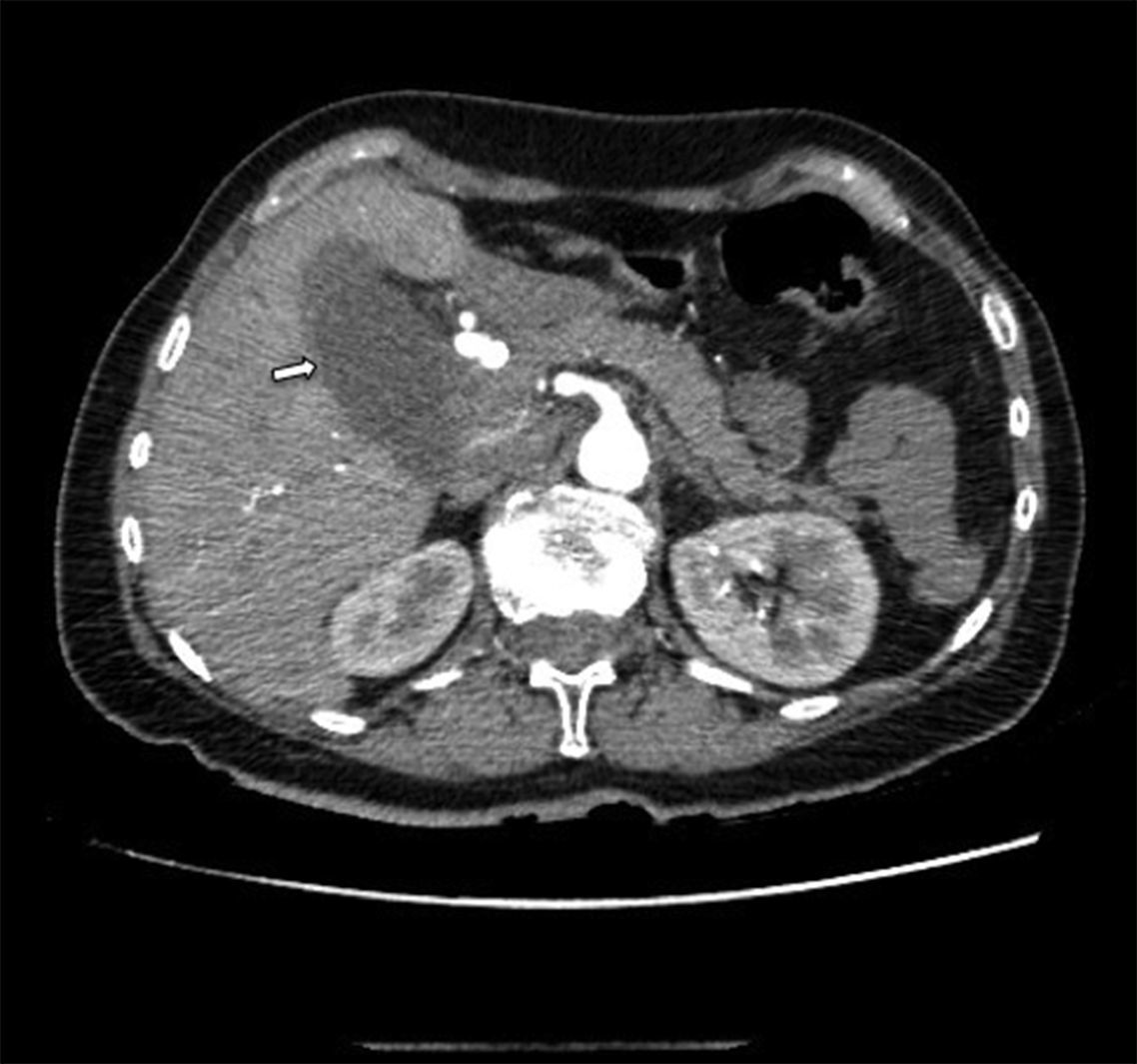

The 8th day after the surgery she presented to the emergency department referring shoulder pain, without abdominal pain or any other symptoms. The physical examination was unremarkable and the blood test showed only leukocytosis (14600/μL) with neutrophilia (79.30%). The CT scan showed a collection at the gallbladder bed (Fig. 1). An external drainage catheter was placed, extracting serous fluid.

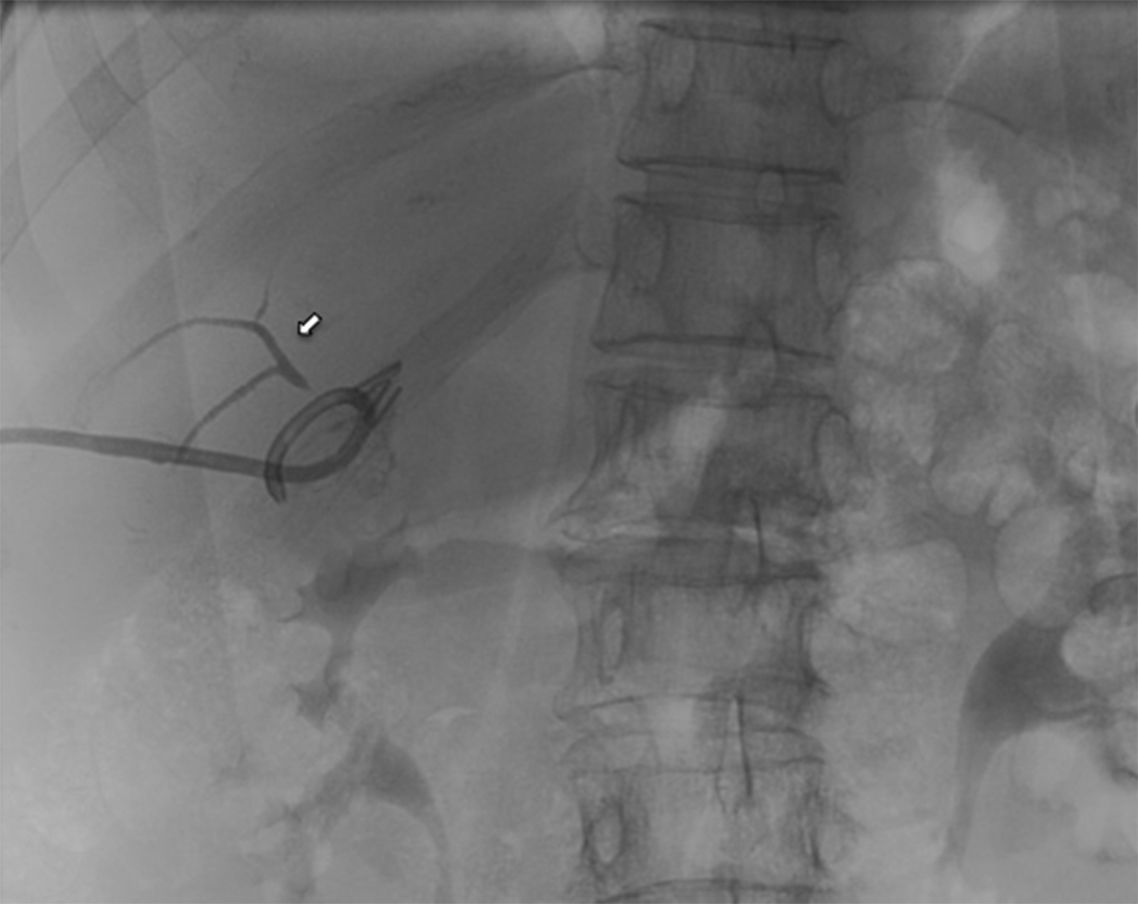

The 9th day after catheter placement an abdominal radiography with contrast was obtained (Fig. 2) showing a subvesical duct (duct of Luschka). The catheter produced bile after that, but remained afebrile and hemodynamically stable, without abdominal pain. The patient was discharged and required outpatient control until the debit stopped and the drainage was removed out of complications.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice for cholelithiasis and one of the most common surgical procedures performed.1 Postoperative biliary leaks remain a significant cause of morbidity in patients undergoing this procedure, occurring in 0.4–1.2% of cases.2 The cystic duct stump is the most common origin of bile leak (78%), followed by subvesicular duct (Luschka duct) in 13%.3

Most of the subvesicular bile ducts belong to biliary system of the right hepatic lobe, and are small (1–2cm in diameter). According to the Strasberg classification, it corresponds to a type A injury.

The clinical presentation may vary. Factors associated with this variability include the volume and distribution of bile in the peritoneal cavity, presence of sterile or infected bile, and presence or absence of a drain. Symptomatic patients after cholecystectomy should undergo investigations with ultrasound or CT scan. If a fluid collection is found, it should be drained under radiological guidance.4

There is no current consensus regarding gold standard treatment of post-operative biliary duct injuries. Some studies have indicated that bile leaks can be successfully treated in 78–100% of patients using endoscopic or radiological interventions.5 The treatment of leaking Luschka ducts depends on the clinical condition of the patients as well as on availability of imaging and interventional modalities.

In asymptomatic patients with low-output bile leaks, percutaneous external drainage might be enough. Avoiding ERCP will avoid the morbidity (ranges from 5 to 10%)6 as post-ERCP pancreatitis, bleeding or duodenal perforation which may occur. Spontaneous resolutions of the leak may arise when subvesicular ducts do not drain significant portions of the parenchyma.

If the leak originates from the end of a Luschka duct that communicates with the central biliary tree, output might be higher and resolution more difficult. In these cases, ERCP with sphincterotomy or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage will be required in order to decrease the intrabiliar pressure to allow its closure.

In patients where the bile leak persists despite the endoscopic or percutaneous management, or symptomatic patients with SIRS criteria, surgical reintervention will be necessary.7,8

Precise knowledge of the local anatomy as well as of anatomic variations decreases the risks as shown by the impact of surgeon experience on the frequency of biliary duct injuries. Staying close to the gallbladder wall during its removal from the fossa is the only known prophylactic measure.9 The final management of this condition will be decided based on the clinical status and the bile outputs.