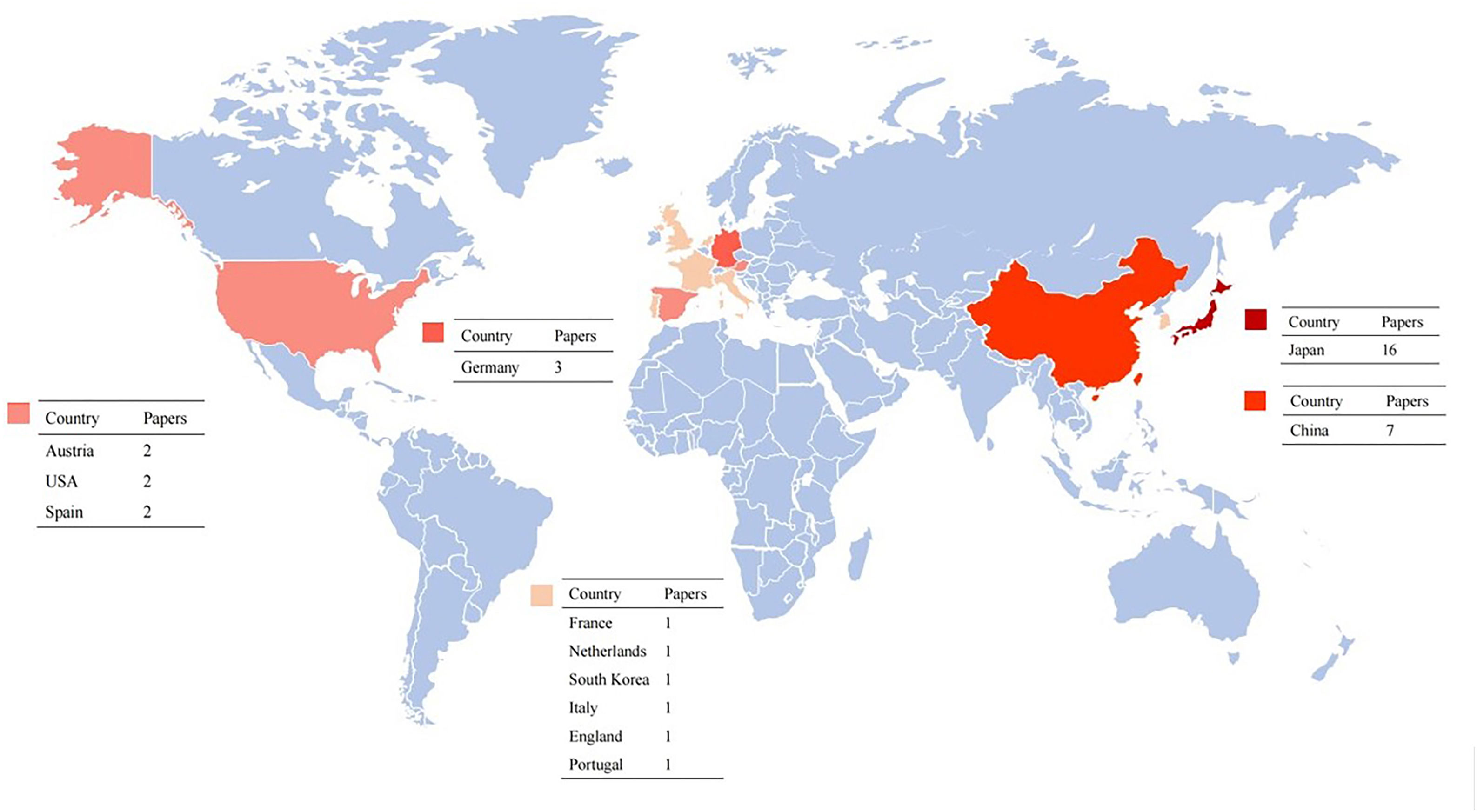

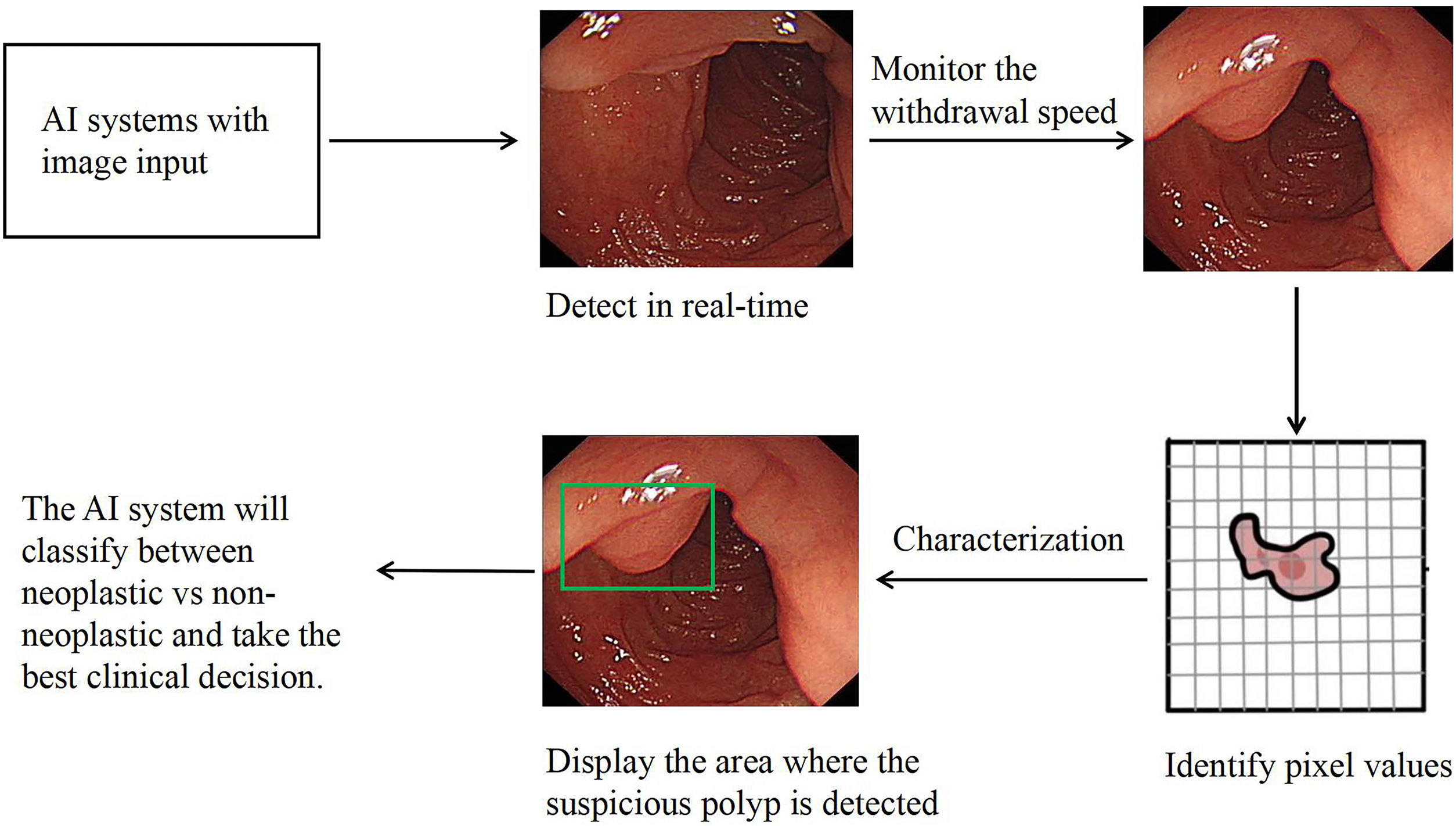

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the common malignant tumors in the world. Colonoscopy is the crucial examination technique in CRC screening programs for the early detection of precursor lesions, and treatment of early colorectal cancer, which can reduce the morbidity and mortality of CRC significantly. However, pooled polyp miss rates during colonoscopic examination are as high as 22%. Artificial intelligence (AI) provides a promising way to improve the colonoscopic adenoma detection rate (ADR). It might assist endoscopists in avoiding missing polyps and offer an accurate optical diagnosis of suspected lesions. Herein, we described some of the milestone studies in using AI for colonoscopy, and the future application directions of AI in improving colonoscopic ADR.

El cáncer colorrectal (CCR) es uno de los tumores malignos más comunes del mundo. La colonoscopia es la técnica de examen crucial en los programas de detección del CCR para la detección temprana de lesiones precursoras y el tratamiento del cáncer colorrectal precoz, pudiendo reducir su morbilidad y mortalidad de manera significativa. Sin embargo, las tasas de pérdida de pólipos agrupadas durante el examen colonoscópico son tan altas como el 22%. La inteligencia artificial (IA) proporciona una forma prometedora de mejorar la tasa de detección de adenomas colonoscópicos (ADR). Podría ayudar a los endoscopistas a evitar la pérdida de pólipos y ofrecer un diagnóstico óptico preciso de las lesiones sospechosas. En este documento, revisamos algunos de los principales estudios sobre el uso de IA en colonoscopia y las perspectivas futuras en la mejora de la ADR colonoscópica.

Artículo

Comprando el artículo el PDF del mismo podrá ser descargado

Precio 19,34 €

Comprar ahora