With the advent of biologic and small molecule therapies, there has been a substantial change in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. These advances have had a great impact in preventing disease progression, intestinal damage and, therefore, have contributed to a better quality of life. Discordance between symptom control and mucosal healing has been demonstrated. This has led to the search for new disease control targets. The treat to target strategy, based on expert recommendations and now a randomized controlled trial, has determined that clinical and endoscopic remission should be the goal of therapy. Biomarkers (fecal calprotectin) can be a surrogate target. Although histological healing has shown benefits, there is inadequate evidence and inadequate therapy for that to be a fixed goal at this time.

This review will focus on therapeutic goals, according to the evidence currently available, and evaluate strategies to achieve them.

Con la llegada de las terapias biológicas y moléculas pequeñas, ha habido un cambio sustancial en el tratamiento de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal, lo que ha permitido evitar la progresión de la enfermedad, el daño intestinal y, por ende, mejorar la calidad de vida de estos pacientes. Se ha demostrado la discordancia entre el control de los síntomas y la curación mucosa, lo que ha llevado a buscar nuevos objetivos de control de la enfermedad. La estrategia de control por objetivos, definido en base a recomendaciones de expertos, ha determinado que se debe buscar en un tiempo establecido la remisión clínica y endoscópica. Hay estudios que han sugerido que los biomarcadores (calprotectina fecal) deben ser parte de los objetivos. Aunque la curación histológica ha demostrado beneficios, aún falta evidencia para que sea considerada como tal. Esta revisión se centrará en los objetivos terapéuticos, con la evidencia disponible actualmente, evaluando además las estrategias para alcanzarlos.

The therapeutic management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) has improved in recent years with new therapeutic options including biologic and small molecule therapies. We evolved from the use of repetitive courses of corticosteroids to an early introduction of therapies that can modify the natural history of the disease.1 Most of the time, the correlation between symptoms and endoscopic disease activity is poor and there is a high risk of reactivation and long-term disease complications. The treat to target approach (T2T) proposes a serial evaluation of disease activity through objective clinical, endoscopic markers and biomarkers. This monitoring will reduce flares and reduce future complications from disease progression. This review will explain the importance of these objectives for Ulcerative Colitis (UC) and Crohn's Disease (CD).

Therapeutic objectivesHistorically IBD therapies sought symptom control, however, following the advent of new therapeutic modalities, more stringent goals could be sought.2 It is mucosal healing (endoscopic remission) which has been associated with a lower risk of reactivation, hospitalization, colectomy requirements, and in the long term, theoretically, lower risk of progression to colorectal neoplasia.3–6

In 2015, a committee of 28 specialists devised the first IBD management consensus (STRIDE) “Selecting therapeutic targets in IBD”, which was based on both clinical and endoscopic objectives.7 This is where the concept of “treat to target” (T2T) was born for IBD (a term that was conceived in rheumatology). It involves the identification of a predefined objective which will be pursued with appropriate therapy with strict monitoring and optimization. This approach has led to better long-term results, including clinical, endoscopic, biomarker, and recently histological objectives.8,9

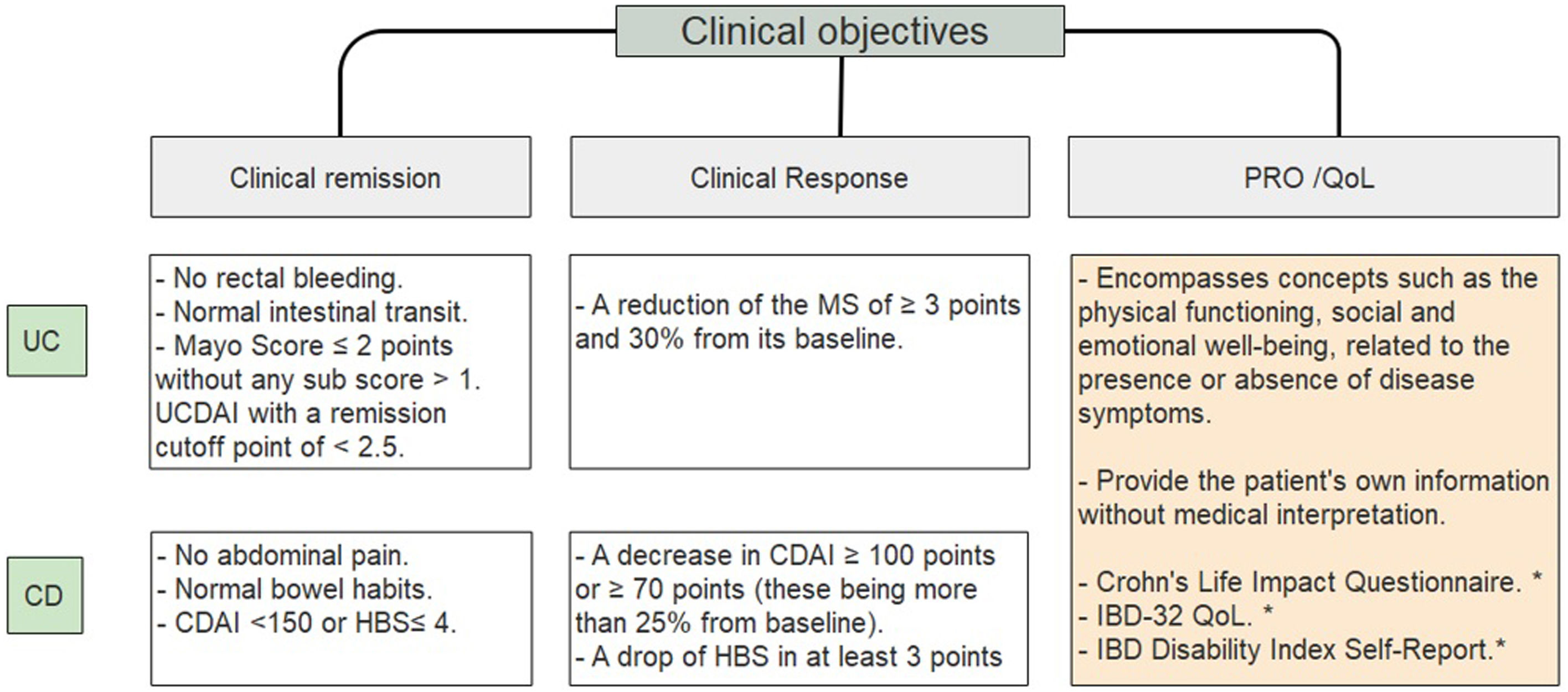

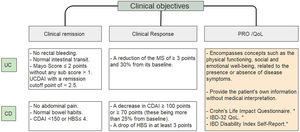

Clinical objectivesIt is important to define and clarify certain concepts such as clinical remission, clinical response and quality of life objectives (Fig. 1).10–14 IBD patients have a significantly lower QoL compared to the general population.15 Disease activity associates with poorer QoL; female gender, fatigue, anxiety levels and depression also contribute to decrease it.16–18 Regarding the latter, there is a significant association between depression symptoms and clinical activity in CD (p=0.007) and UC (p=0.005).19 A French national cross-sectional study evaluating PRO showed that 55.1% of CD patients and 37.3% of UC patients had a poor quality of life.20

Clinical objectives in IBD.10–14 UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn's disease; UCDAI, Ulcerative colitis disease activity index; CDAI, Crohn's disease activity index; HBS, Harvey Bradshaw score; PRO, patient related outcome; QoL, quality of life. * Systematic review showed moderate validation for these scores14.

Guidelines recommended that clinical follow-up should be every 3 months in case of active disease and every 6–12 months during remission.7

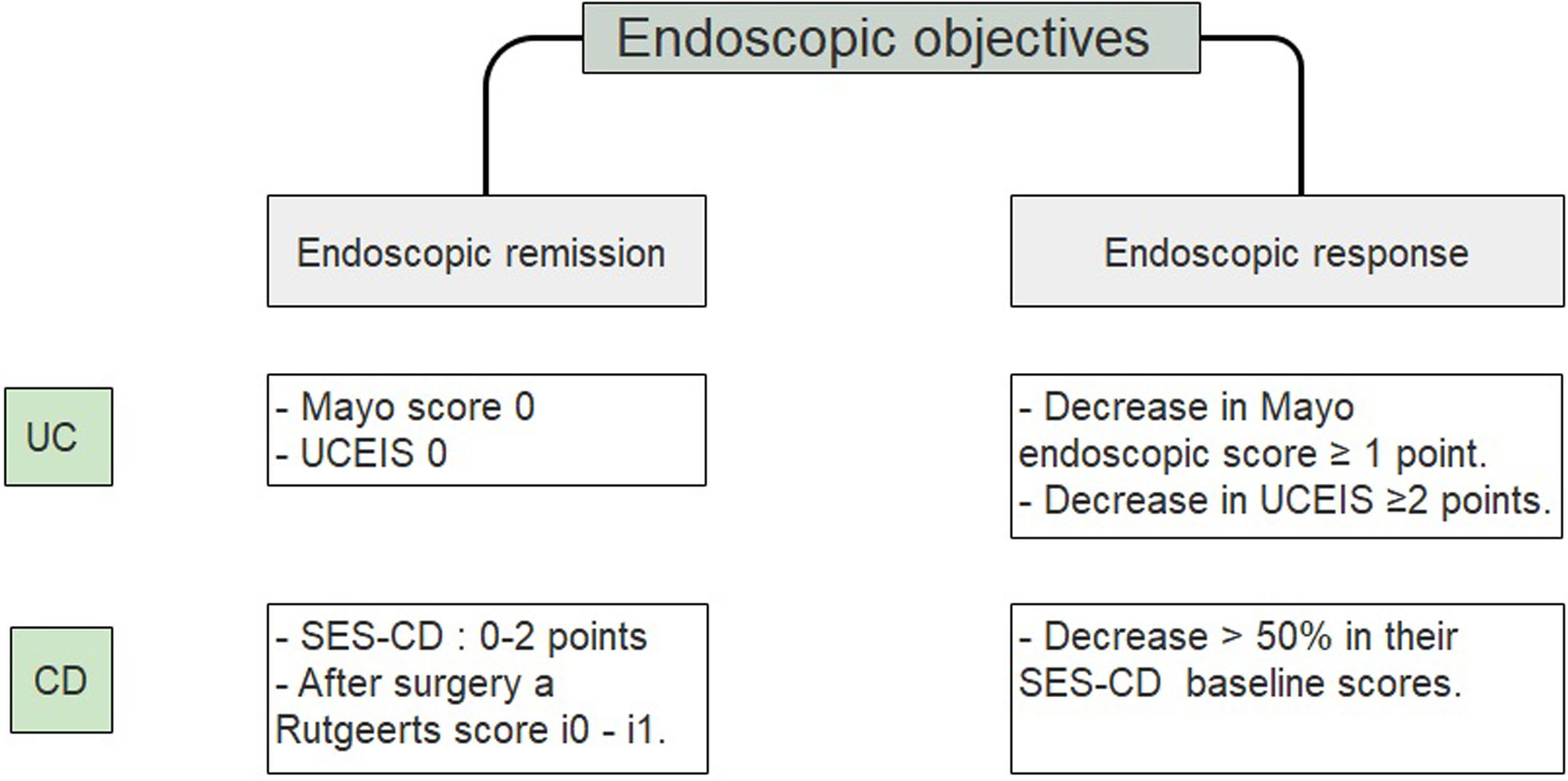

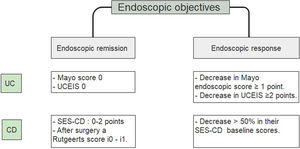

Endoscopic objectivesRecent studies both in clinical trials and in post hoc analysis, have made it possible to recommend endoscopic healing as an objective in patients with IBD. This objective is associated with a better prognosis, lower hospitalization rates, a lower risk of relapse and of surgical interventions.21,22

STRIDE recommends evaluating the resolution of ulcers and mucosal friability within 6–9 months in CD and 3–6 months in UC after starting therapy.7 In a recent systematic review, there were no variations in the times suggested to assess endoscopic resolution.23,24

A study that included a 6-month follow-up in 248 UC patients observed a higher percentage risk of relapse in patients who had reached an index of Mayo of 1 vs the group with a Mayo of 0, (36.6% vs. 9.4% with p<0.001).25 Since accumulated evidence would suggest there is a better prognosis, it has been proposed to define endoscopic remission in UC as a UCEIS of 0 or an endoscopic Mayo of 0 points (Fig. 2).26–29 Recently, deep remission (clinical and endoscopic) in early, moderate to severe CD patients has been associated with decreased risk of disease progression so endoscopic remission became a major stake in CD.30

Endoscopic objectives in IBD.26–29 UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn's disease; UCEIS, ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity; SES CD, simple endoscopic score for Crohn's disease.

The utility of FC in disease monitoring and as a predictor of relapse has been established.31,32 It has a high sensitivity regarding endoscopic activity in both UC and CD, however, in CD the sensitivity changes according to phenotype and location.33

Using ROC curves, it was possible to determine that in UC patients a FC<200mcg/g (AUC=0.74) correlated with an endoscopic Mayo of 0, with sensitivity (S), specificity (E), positive predictive value (PPV) and negative (NPV) of 0.75, 0.8, 0.22 and 0.98 respectively. It was also observed that the same FC cut-off point reflected histological remission with an S, E, PPV and NPV of 0.71, 0.76, 0.30 and 0.95 respectively.34 Although the FC threshold that would indicate mucosal healing is still in validation.35 In a recent update on T2T management of UC, AGA proposes a cut point of 100mcg/g to consider remission of the disease,23 this being confirmed by other authors.36 FC concentration can vary depending on the location of the disease, being lower at the ileal level. However, an altered value of this parameter can help to make treatment decisions.37 Thus, in patients with asymptomatic CD, two measurements of elevated FC can predict a higher risk of relapse in the following 3 months.38 Therefore, it is recommended to carry out a FC 2–3 months after starting therapy.39

FC is also used to monitor post-surgical CD, with values <100μg/g suggestive of remission.40 In turn, FC could also be used in those patients who are scheduled to withdraw drugs. In a prospective study of 160 patients with IBD, FC levels>100μg/g at 8 weeks after therapeutic de-escalation was the best threshold to predict clinical relapse in these patients with a HR=3.96 [2.47–6.35]; p<0.0001.41

Radiological objectivesImaging is a very attractive non-invasive monitoring option. However, to date, studies only support its use in patients with CD.23,42 In a retrospective study of 150 patients with CD observed for 9 years, those with resolution of the inflammation by either computed tomography enterography or magnetic resonance enterography were associated with a decrease in hospitalizations (HR=0.28, 95 CI −0.15 to 0.50) and surgery (HR=0.34, 95 CI 0.18–0.63).43 Other studies have also shown that achieving radiological remission would be associated with a lower probability of requiring therapy optimization, hospitalizations and surgery at one-year term (HR=0.27, 95% CI 0.13–0.56; p=0.001.44

Diffusion resonance modalities have shown high sensitivity in detecting mucosal lesions. They could have potential applicability in the future, with the Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity (MaRIA) and the Nancy Index being the most widely used.45–47

In perianal CD, studies have evaluated the percentage of remission with anti-TNF by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with a good inter-observer correlation (p<0.001). To date new scores are sought to achieve greater precision.48,49

Ultrasound (US) is another low-cost, widely available, non-invasive method that allows evaluating patients with IBD. This technique is widely used in Europe. It can determine wall thickening, fat compromise, masses, abscesses, or fistulas, and Doppler can help assess the increase in local vasculature indicating inflammation. Although there are activity scores, none have yet been validated.50,51 The European guidelines for Crohn's and Colitis conclude that both MRI and US have similar performance in evaluating activity in ileocolonic CD.52 A recently published study including 80 CD patients treated with anti-TNF for at least one year, confirmed the usefulness of ultrasonography as a non-invasive method in the follow-up and management of patients with CD.53

In STRIDE, it was recommended to evaluate the resolution of the inflammation by images in CD when it was not possible by endoscopy, but not in UC.7 To date, there are still no changes in these objectives.

Histological objectivesHistological remission was not recommended as a therapeutic objective in the AGA systematic review in 2019.23 However, different studies have suggested that achieving histological remission in UC may be associated with a better long-term prognosis, regarding relapse-free periods, use of corticosteroids and hospitalizations.54 Danese et al., recently published that complete remission should be considered as one of the main therapeutic objectives in UC since it is possible to find histological alterations even in endoscopically healthy mucosa.55

Patients who achieve complete remission (clinical, endoscopic and histological remission), had a lower risk of clinical relapse than the group that persisted with histological activity.56,57 The presence of inflammatory activity in biopsies in patients with endoscopic mucosal remission would be associated with an increased risk of clinical relapse at 18 months.58 Even though only complete histologic normalization of the bowel (non segmental normalization) was associated with improved relapse-free survival (HR 0.23; 95 CI 0.08–0.68; p=0.008).59

In a Cochrane review it was established that Nancy Index and Robarts Histopathology Index (RHI) are the histological indices with the highest validity. However, until now none of them have been fully validated to determine the cut-off point to define histological cure.59 This can be observed in the VARSITY study, which is the first study comparing “head to head” two biologic therapies (adalimumab vs. vedolizumab) in patients with moderate to severe UC. Geobes and RHI scores were used to define histological cure. The remission values at 52 weeks for Geobes were 10% for vedolizumab and 3% for adalimumab and for RHI 38 and 20% respectively.60,61 The role of histological remission in CD is less clear and what is known is mainly based on retrospective studies. However, in a recent study comparing ustekinumab vs placebo, histological response at 8 weeks was associated with a lower risk of relapse both clinically and endoscopic at 44 weeks.62 Furthermore, in patients with ileal CD, histological rather than endoscopic remission was associated with a lower risk of clinical relapse (HR 2.05; p=0.031), need to scale up in therapies (HR 2.17; p=0.011) and use of corticosteroids (HR 2.44; p=0.018).62

Currently, studies that validate scaling up therapy or de-escalation are still lacking.63

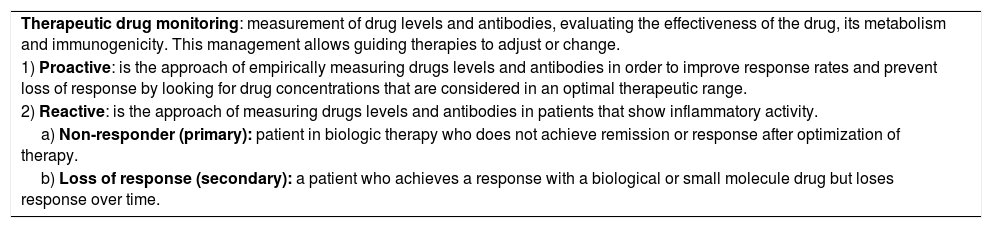

How do we achieve those goals?The introduction into clinical practice of pharmacological monitoring of anti-TNFs, determining their serum levels or the presence of antibodies against the drug, has allowed personalized therapy and thus a better strategy to achieve therapeutic objectives, definitions in Table 1.64 However, pharmacological monitoring has not currently been suggested for clinical practice for other biologics (vedolizumab or ustekinumab) nor small molecule therapy (tofacitinib).65,66 It must be considered that 30% of patients may have a primary failure despite optimization of therapy. Up to 50% of those who achieve endoscopic and clinical remission goals may have a loss of response.67 The CALM study showed a 48-week endoscopic remission rate of 45.9% in tight control (the one that uses objective markers of inflammation, which allows them to optimize therapies if necessary) vs 30.3% in routine clinical control (based only on achieving clinical objectives) with p=0.010.68 In a follow-up study of the CALM study with a mean of 3 years, those who achieved early (at 12 weeks) and deep remission had a lower risk of disease progression regardless of being followed with a conventional or strict approach.69

Definitions and concepts in therapeutic goals in IBD64.

| Therapeutic drug monitoring: measurement of drug levels and antibodies, evaluating the effectiveness of the drug, its metabolism and immunogenicity. This management allows guiding therapies to adjust or change. |

| 1) Proactive: is the approach of empirically measuring drugs levels and antibodies in order to improve response rates and prevent loss of response by looking for drug concentrations that are considered in an optimal therapeutic range. |

| 2) Reactive: is the approach of measuring drugs levels and antibodies in patients that show inflammatory activity. |

| a) Non-responder (primary): patient in biologic therapy who does not achieve remission or response after optimization of therapy. |

| b) Loss of response (secondary): a patient who achieves a response with a biological or small molecule drug but loses response over time. |

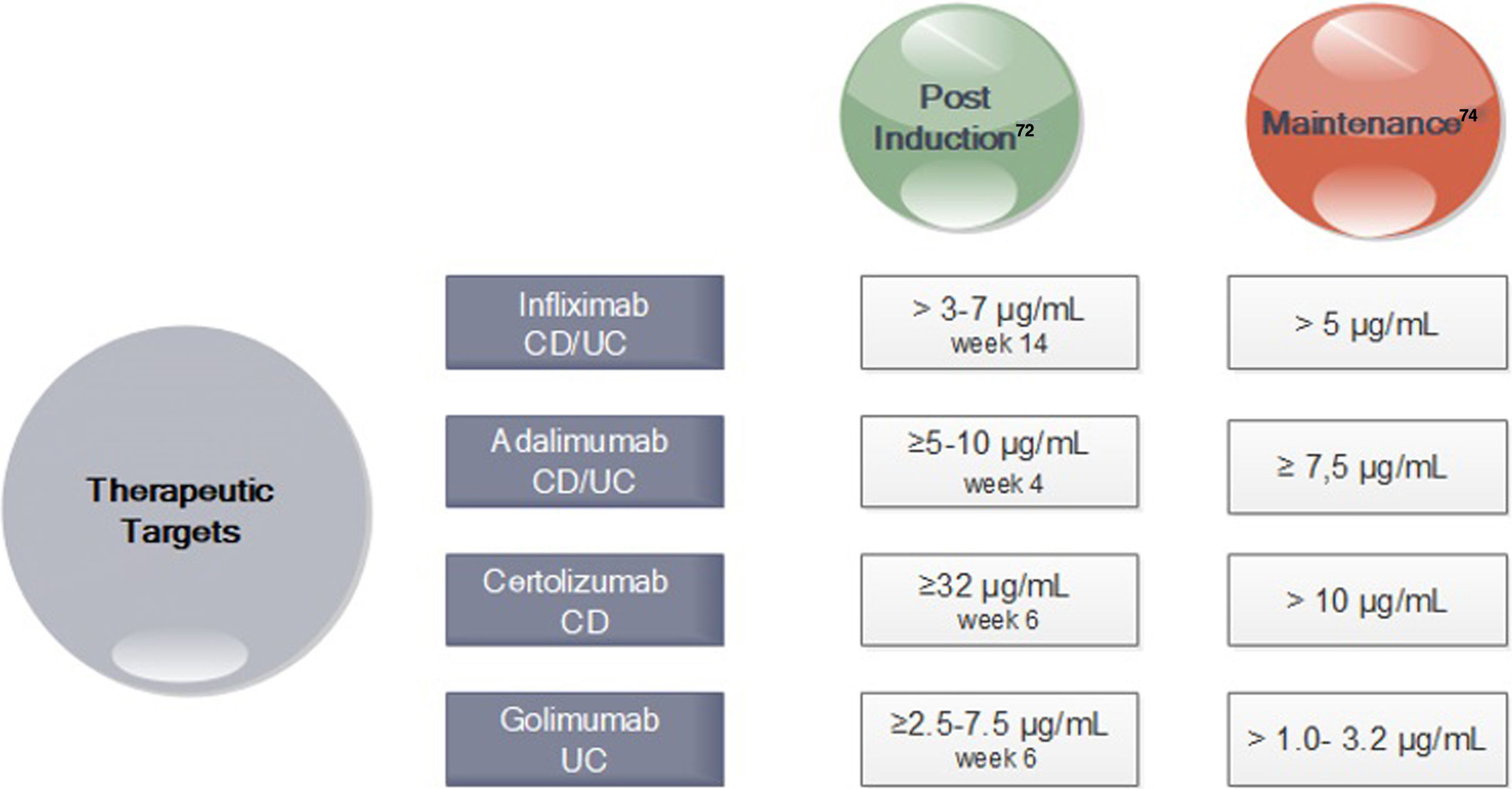

In turn, in subsequent analyzes of the TAILORIX study showed that more than the strategy used, it was the high levels of infliximab in week 2 (>23.1mg/ml) and week 6 (>10mg/ml) that were associated with mucosal healing at 12 weeks.70 Optimal therapeutic ranges of anti-TNF that ensure an optimal response have been established for both induction and maintenance (Fig. 3).71–74

Drug Concentration Targets for Anti-TNF agents after Induction and during Maintenance71-74. *CD Crohn's disease; UC ulcerative colitis. *In perianal disease would be necessary high levels of anti-TNF.

The AGA therapeutic monitoring guidelines recommend a reactive approach,73 meaning testing in those patients who present with activity, without making a recommendation about the proactive strategy. Others, however, recommend following a reactive strategy (in those non-responders or secondary loose response) as well as a proactive one (testing to maintain a desired level or to titrate induction therapy).74 An expert consensus, using the Delphi method, recommends checking levels of anti-TNF at the end of induction, once during maintenance and in primary failure or loss of secondary response. This strategy is not recommended with other biological therapies.75 In addition, the proactive strategy would allow for a more rational confrontation when considering therapy retreat.76,77

Is T2T practiced in “the real” world?Although the need for objective management is clear, studies have shown differences in adherence to these. A study carried out in the United States found that in 56.4% of patients with CD and in 67.8% of the patients with UC, proactive management was performed in a 24-month follow-up, with colonoscopy being the instrument most widely used (87.9%).78 A survey in New Zealand showed that 93% of gastroenterologists (40/43) measured levels of anti-TNF in the follow-up of patients treated with anti-TNF. The main reason for measuring them was lack of primary response or loss of response (87%).79

ConclusionEarly disease control, with close monitoring and pre-established goals may be the best way to change the course of the disease.80

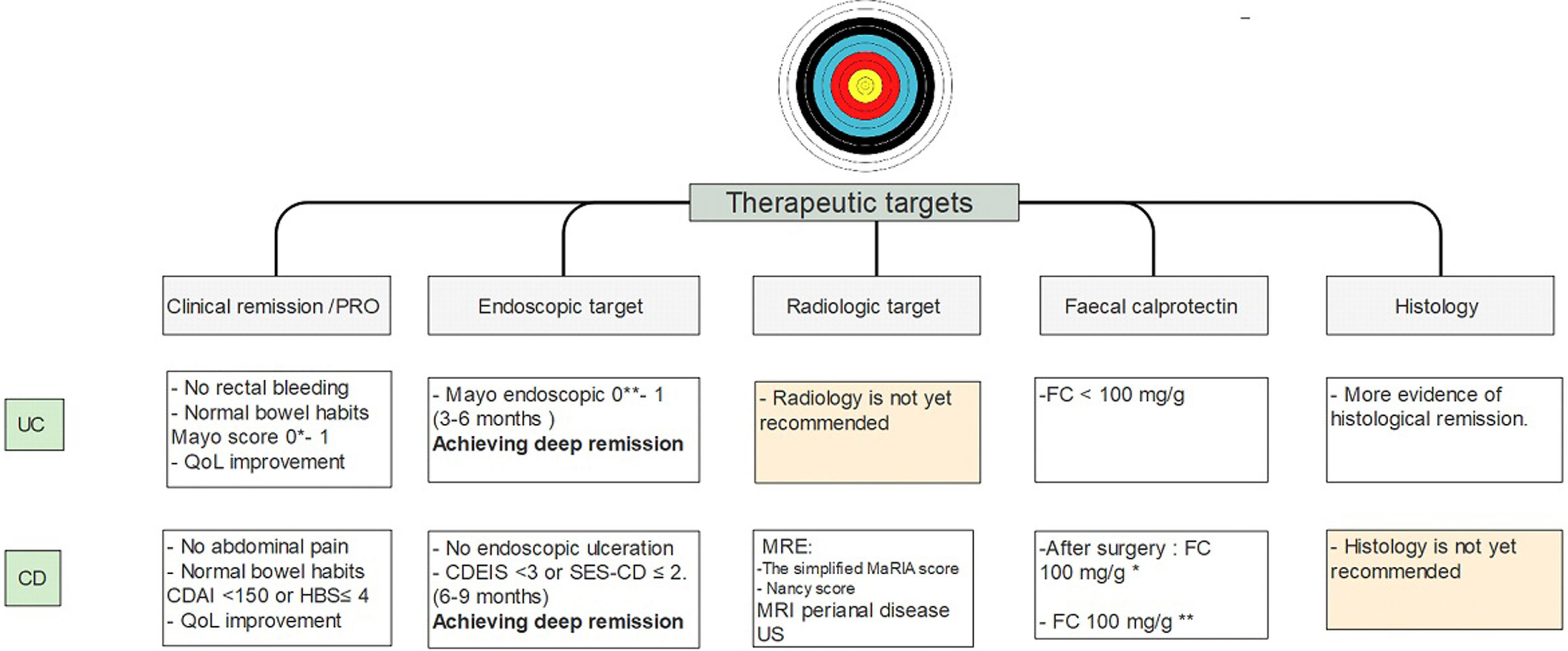

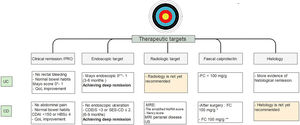

Over the years, the therapeutic objectives of IBD have changed, advancing from clinical remission to deep remission (which includes clinical and endoscopic remission). Today, it is even more stringent, including quality of life indicators (PRO) and biomarkers, such as FC, in the follow-up of patients with IBD and may soon include histologic remission.

It is important to emphasize that there is more and more information that close monitoring of these objectives may change the course of the disease. These would indicate that achieving early histological remission, may avoid the long-term risks of colorectal cancer.81 Current therapeutic goals are described in Fig. 4.

Treat to target approach in IBD patients10-14,26-28,37-40,54-58,62. UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn's disease; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; US, ultrasonography; FC, fecal calprotectin. * Strongly suggest no recurrent disease. ** Highly associated with clinical remission at 1 year.

Considering the current therapeutic objectives, the question that must be answered is what to do in those patients who are in clinical and endoscopic remission but maintain histological activity. Do we need to optimize? In this, we must undoubtedly consider each patient's risk factors and decide on a case-by-case.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.