Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is very prevalent, with a positive serology being present in two thirds of the population.1 Like other viruses in the herpes family, CMV remains latent in the body and can be reactivated in immunosuppressive states.2 The most commonly affected organs are the retina, lungs, oesophagus, central nervous system and colon.3 Colonic CMV has been described in the literature either as a form of colitis2 or as solitary ulcers4 found in immunocompromised patients, although massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding is a rare complication of colonic CMV.4

We present the case of a 62-year-old man with a history of supraventricular tachycardia who was being monitored by the cardiology department and treated with atenolol. The patient was admitted to hospital due to haematuria and kidney failure. In the ultrasound performed, a suspected malignant lesion was identified in the bladder. A cystoscopy was scheduled, where a biopsy of the bladder was performed, leading to a diagnosis of granulomatous cystitis. Urine cultures also tested positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

The patient received tuberculostatic treatment, but due to the infection, he presented with a contracted bladder with secondary obstructive uropathy, which required drainage through a bilateral percutaneous nephrostomy. Due to a lack of response, a Bricker uretero-ileostomy urinary diversion was performed without cystectomy using the ureter of the left kidney; the ureter of the right kidney appeared to be fibrous. The patient presented with post-operative kidney failure and acute pulmonary oedema signs, which required admission to the ICU and orotracheal intubation for 17 days.

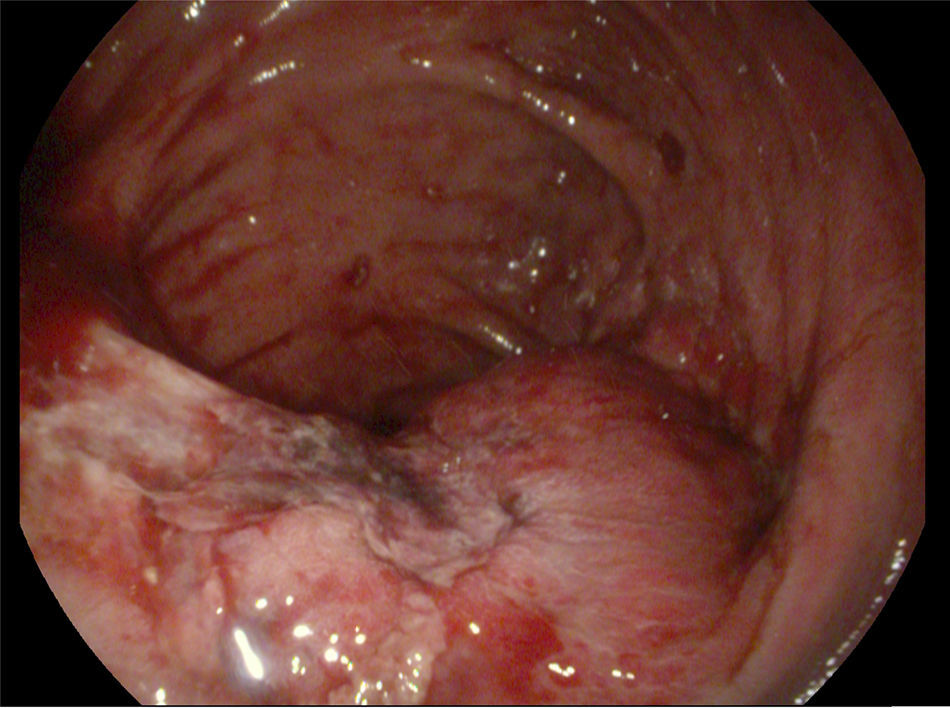

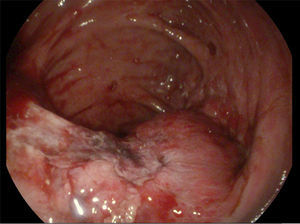

At the ICU, the patient presented with painless rectal bleeding with secondary anaemia. A full colonoscopy was performed and two ulcers were detected, one in the ileocaecal valve (Fig. 1) and the other in the rectum, both with fibrin. A biopsy was taken for an anatomopathological study and a sample was sent for culture, with no blood remnants being found during examination. Three days later the results of the anatomopathological study were received, revealing inclusions suggestive of CMV infection for which intravenous treatment with ganciclovir was initiated. The colonoscopy was repeated five days later because rectal bleeding and secondary anaemia persisted, with fresh blood remnants being observed in the colon (bilious remnants in the ileum) and an ulcer in the terminal ileum with a visible vessel that was treated using sclerotherapy with adrenaline and Etoxisclerol.

The patient continued to experience rectal bleeding and anaemia, requiring, from the start, a total of eight units of packed red blood cells. During this time his kidney condition deteriorated and so dialysis was initiated. One week after the first colonoscopy, yet another one was performed, observing rectal ulcer with no signs of recent bleeding. The ulcer in the ileocaecal valve was also observed with a blood clot that oozed blood, and was subsequently removed. The Hemospray was applied to this ulcer, stopping the bleeding.

From the moment the endoscopy was performed, the patient presented with no signs of rebleeding and maintained stable haemoglobin values. His kidney failure progressed, with significant deterioration in his overall condition, finally presenting with acute pulmonary oedema that led to his death 72h after the colonoscopy.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding caused by solitary colonic ulcers secondary to CMV is a rare complication, with cases having been reported in patients with comorbidities like kidney transplant and diabetes mellitus. Intravenous ganciclovir has been used to treat bleeding caused by solitary ulcers, while surgery has been used in cases of refractory bleeding.4,5

Recently, haemostatic agents such as TC 315 (Hemospray®, Cook Medical) have been introduced as part of the endoscopic therapeutic arsenal for the management of gastrointestinal bleeding, because they are effective in controlling non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. They are especially useful for active bleeding such as that caused by gastrointestinal tumours.6 Their usefulness in treating variceal gastrointestinal bleeding has also been recently demonstrated.7

In the literature their use has been described in several cases of lower gastrointestinal bleeding in the context of polypectomy, actinic cheilitis, diverticular bleeding and colorectal cancer, with immediate haemostasis being achieved in 100% of cases.8 In our case, given the refractory nature of the bleeding, it was decided that Hemospray should be used in both the intravenous treatment for CMV and the endoscopic therapy, which controlled the bleeding effectively. However, despite stopping the bleeding, the patient's overall deterioration eventually led to his death.

Refractory bleeding caused by an ulcer in the colon secondary to a CMV infection is a rare complication. The use of Hemospray may be an effective method of controlling bleeding.

Please cite this article as: Diez-Rodríguez R, Castillo-Trujillo RS, González-Bárcenas ML, Pisabarros-Blanco C, Barrientos-Castañeda A. Utilidad del Hemospray en paciente con hemorragia digestiva baja refractaria secundaria a úlcera en ciego por citomegalovirus. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:40–42.