Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) stand as distinct diseases, yet occasionally intertwine with overlapping features, posing diagnostic and management challenges. This recognition traces back to the 1970s, with initial case reports highlighting this complexity.

Diagnostic scoring systems like IAIHG and simplified criteria for AIH were introduced but are inherently limited in diagnosing variant syndromes. The so-called Paris criteria offer a diagnostic framework with high sensitivity and specificity for variant syndromes, although disagreements among international guidelines persist.

Histological findings in AIH and PBC may exhibit overlapping features, rendering histology alone inadequate for a definitive diagnosis. Autoantibody profiles could be helpful, but similarly cannot be considered alone to reach a solid and consistent evaluation.

Treatment strategies vary based on the predominant features observed.

Individuals with overlapping characteristics favoring AIH ideally benefit from corticosteroids, while patients primarily manifesting PBC features should initially receive treatment with choleretic drugs like ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA).

La hepatitis autoinmune (HAI) y la colangitis biliar primaria (CBP) son enfermedades distintas, pero ocasionalmente se entrelazan con características superpuestas, lo que plantea desafíos diagnósticos y de manejo. Este reconocimiento se remonta a la década de 1970, con los primeros informes de casos que destacaban esta complejidad.

Se introdujeron sistemas de puntuación diagnóstica como el IAIHG y los criterios simplificados para la HAI, pero están inherentemente limitados para diagnosticar síndromes variantes. Los llamados Criterios de París ofrecen un marco diagnóstico con alta sensibilidad y especificidad para los síndromes variantes, aunque persisten desacuerdos entre las guías internacionales.

Los hallazgos histológicos en la HAI y la CBP pueden mostrar características superpuestas, lo que hace que la histología por sí sola no sea adecuada para un diagnóstico definitivo. Los perfiles de autoanticuerpos podrían ser útiles pero, de manera similar, no pueden considerarse por sí solos para alcanzar una evaluación sólida y consistente.

Las estrategias de tratamiento varían según las características predominantes observadas.

Las personas con características superpuestas que favorecen la HAI idealmente se benefician de corticosteroides, mientras que los pacientes que principalmente manifiestan características de CBP deben recibir inicialmente tratamiento con fármacos coleréticos, como el ácido ursodeoxicólico (UDCA).

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) are distinct diseases; yet, a small percentage of individuals can present with a mixed phenotype of AIH-like and PBC-like features. Whether these cases represent the overlap of PBC and AIH, a variant syndrome of either diseases or a separate condition is still a matter of debate among experts. The lack of consensus and the rarity of the condition have hampered well-powered studies, which makes diagnosis and treatment still a clinical challenge.

In this review, we summarize the historical perspective on this topic together with the available evidence and provide future perspectives.

Historical overviewRecognition of individual cases exhibiting overlapping features of AIH and PBC has been a longstanding observation. Starting from the 1970s, several studies and case reports were published on this matter.

In 1969, Doniach et al.1 proposed a unified immune origin for AIH, which could result in the development of either active chronic hepatitis or what was referred to as primary biliary cirrhosis at that time, depending on whether the condition primarily targets hepatocytes or bile ducts.

In a study conducted in 1972 by Cooksley et al.,2 30 patients with active chronic hepatitis were observed prospectively for three years: none of them reported a history of excessive alcohol consumption or recent exposure to recognized hepatotoxic agents. Among them, 14 displayed symptoms such as prolonged jaundice, itching, high cholesterol levels and elevated serum alkaline phosphatase. A notable aspect of this study involves a female patient aged 32, as her clinical, serological and histological characteristics shifted over the observation period, transitioning from those typically associated with active chronic hepatitis to those indicating a probable PBC.

In 1987, Brunner et al.3 published a case report where three female patients experienced symptoms of chronic liver disease. The characteristics of this liver disease were consistent with chronic destructive non-suppurative cholangitis at the clinical, histological, and biochemical level. Interestingly, none of these patients tested positive for antimitochondrial antibodies, but they all exhibited high levels of antinuclear antibodies (ANA); whether these were PBC-specific ANAs is unknown. Notably, two of these patients were related as mother and daughter, with the daughter having two children of her own (aged 10 and 12), both of whom showed low levels of ANA but had normal liver function tests. Additionally, female family members of the third patient also had ANA in their blood but normal liver enzyme test results. In contrast to genuine chronic destructive nonsuppurative cholangitis, the three patients responded positively to immunosuppressive therapy including prednisone and azathioprine.

A noteworthy date in the field of autoimmune liver diseases is 1992, when the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) introduced the Scoring System for AIH.4 This innovative system was designed to provide a standardized and objective method for diagnosing AIH, aiming to reduce variability and improve diagnostic accuracy across different clinical settings. The scoring system assigns points to various clinical, laboratory, and histological features, categorizing patients into probable (score 10–15 points) or definite (score>15 points) cases of AIH. Since its inception, the IAIHG scoring system has undergone several refinements and revisions to enhance its specificity and sensitivity, reflecting advances in understanding the disease.

However, it is crucial to emphasize that the IAIHG score was not originally intended for diagnosing AIH in patients with PBC. This becomes evident when considering that the presence of anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA) or biliary changes seen in liver biopsies, which are characteristic of PBC, can negatively affect the diagnostic scores. These elements were not adequately addressed in the original scoring system, leading to potential misclassification or underdiagnosis of AIH in patients who exhibit overlapping features of both AIH and PBC.

When assessing how many cases of PBC exhibited AIH characteristics, a series of studies conducted between 1998 and 20025–8 re-evaluated 446 PBC patients, utilizing either the IAIHG score, or standard clinical parameters associated with AIH. The prevalence of probable or definite AIH in PBC patients varied across the four different studies, with percentages identified as 18%, 2%, 9%, and 19%.

In 2008, simplified criteria for AIH were introduced,9 and in this scoring system the presence of AMA or histological findings associated with PBC are no longer considered.

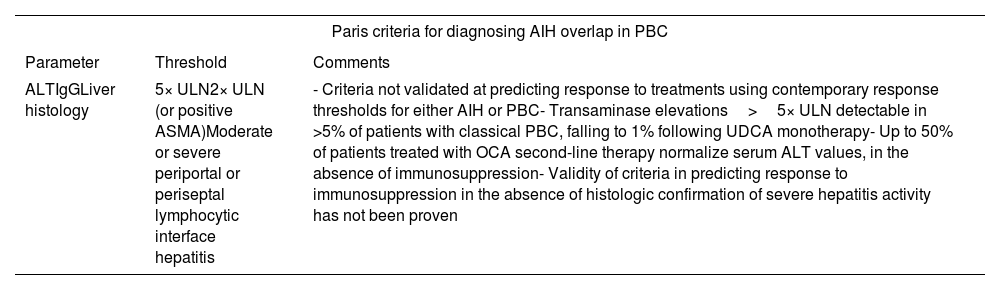

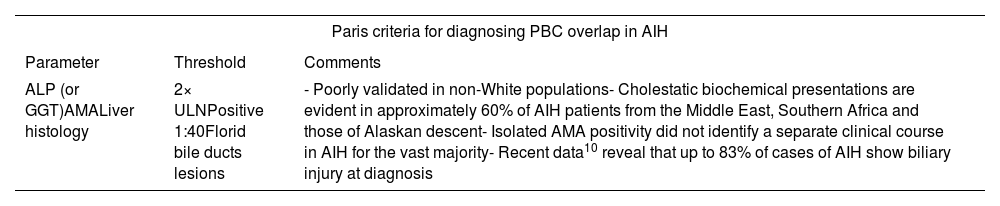

Navigating the pros and cons of Paris criteriaIn 1998, Chazouilleres and colleagues7 proposed comprehensive diagnostic criteria for the PBC–AIH syndrome known as the Paris criteria (Tables 1 and 2). The presence of at least two out of three well-established characteristics associated with each condition is required to establish a definite diagnosis of PBC–AIH.

Paris criteria for diagnosing AIH overlap in PBC.

| Paris criteria for diagnosing AIH overlap in PBC | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Threshold | Comments |

| ALTIgGLiver histology | 5× ULN2× ULN (or positive ASMA)Moderate or severe periportal or periseptal lymphocytic interface hepatitis | - Criteria not validated at predicting response to treatments using contemporary response thresholds for either AIH or PBC- Transaminase elevations>5× ULN detectable in >5% of patients with classical PBC, falling to 1% following UDCA monotherapy- Up to 50% of patients treated with OCA second-line therapy normalize serum ALT values, in the absence of immunosuppression- Validity of criteria in predicting response to immunosuppression in the absence of histologic confirmation of severe hepatitis activity has not been proven |

Paris criteria for diagnosing PBC overlap in AIH.

| Paris criteria for diagnosing PBC overlap in AIH | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Threshold | Comments |

| ALP (or GGT)AMALiver histology | 2× ULNPositive 1:40Florid bile ducts lesions | - Poorly validated in non-White populations- Cholestatic biochemical presentations are evident in approximately 60% of AIH patients from the Middle East, Southern Africa and those of Alaskan descent- Isolated AMA positivity did not identify a separate clinical course in AIH for the vast majority- Recent data10 reveal that up to 83% of cases of AIH show biliary injury at diagnosis |

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AMA, anti-mitochondrial antibody; ASMA, anti-smooth muscle antibody; IgG, immunoglobulin G; OCA, obeticholic acid; SMA, smooth muscle antibody; UDCA, ursodeoxycholic acid; ULN, upper limit of normal.

According to Kuiper et al.,11 the Paris diagnostic criteria exhibit high levels of sensitivity (92%) and specificity (97%) in identifying variant syndromes (VS). In this retrospective-single center study, the authors gathered and analyzed data from all patients diagnosed with PBC, AIH and VS from January 1990 to January 2008 (for a total of 134 patients). To evaluate the effectiveness of the Paris criteria, researchers chose to identify a reference group of patients with VS based on their clinical, laboratory and histological characteristics, without applying stringent diagnostic criteria. Remarkably, the Paris criteria demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy in this categorized approach. On the contrary, the clinical utility of the revised and simplified AIH scoring system was less dependable, with a sensitivity and specificity of 40 and 17% respectively.

Nevertheless, as highlighted by Adeyi O. et al.,12 the Paris criteria, despite achieving some success, introduce significant diagnostic challenges by requiring the presence of two out of three parameters for each disease. According to these criteria, a biopsy featuring PBC characteristics, along with “interface hepatitis” and positive ASMA, regardless of transaminase levels (the optional third parameter), would qualify as a VS. However, the problem lies in the lack of specificity associated with ASMA, and the “interface hepatitis” is not an uncommon feature of PBC. This raises concerns about potential overdiagnosis of PBC–AIH variant syndrome. In our experience, however, we often observe that the issue arises from the coexistence of ANA positivity and interface hepatitis in PBC, or interface hepatitis alone.

Variant or overlap syndrome?The questions that might arise at this point are: is it plausible that AIH and PBC constitute a continuous spectrum within autoimmune liver disease, with AIH/PBC individuals positioned at the center? Are these patients simultaneously affected by two distinct diseases? Alternatively, can these patients be reasonably classified as either experiencing a cholestatic manifestation of AIH or a hepatic manifestation of PBC? Is it a matter of variant presentations or an overlap between the two conditions?

Exploring variant forms of a disease involves recognizing subtypes or alternative expressions of the condition: in AIH, variant forms may manifest through atypical presentations, such as autoantibody negativity or the occurrence of giant cell hepatitis, diverging from the classical or typical manifestation of the disease. In certain instances, the presence of syncytial multinucleated hepatocyte giant cells suggests that many cases of giant cell hepatitis, often called so, probably represent a distinct variant within the spectrum of AIH.13

Conversely, the concept of overlap syndrome arises when features of two distinct diseases coexist. In the context of AIH, overlap syndromes involve the simultaneous presence of AIH and features of another liver disease, such as PBC or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). This suggests that individuals meet diagnostic criteria for both conditions concurrently.

In essence, when there is convergence in clinical features, serologic profile, and histopathology, the diagnosis of an overlap syndrome should be contemplated.

In this regard, A.W. Lohse et al.14 comparative study outlines the clinical and histological features of 20 patients exhibiting overlapping characteristics of PBC and AIH. Their objective was to investigate whether this overlap syndrome constitutes a distinct entity, a continuous spectrum between the two conditions (PBC and AIH), or a subgroup of either of these conditions. It was clearly demonstrated that these patients indeed displayed characteristic features of both AIH and PBC, thus indicating an apparent overlap of the two conditions.

According to R. Poupon et al.,15 the question of whether PBC–AIH overlap represents a distinct entity or a variant of AIH or PBC remains uncertain. Furthermore, aside from the PBC–AIH VS, there are documented cases where individuals with characteristic features of either PBC or AIH transitioned from one disease to the other over time. The consecutive manifestation of both diseases lends support to the idea that these patients are dealing with two concurrent autoimmune conditions. This observation aligns with the established fact that autoimmune diseases tend to co-occur in 5% to 10% of cases, reinforcing the concept that PBC–AIH VS involves the simultaneous presence of two distinct autoimmune disorders.

According to M.K. Washington,13 the term overlap should be used judiciously to cases of PBC that are otherwise typical but exhibit prominent interface hepatitis, considering that true overlap syndromes do occur but are fairly rare, constituting less than 10% of PBC patients.

In line with this, the IAIHG16 recommends classifying patients with autoimmune liver disease based on predominant features, distinguishing between AIH and PBC. Overlapping features should not be considered as distinct diagnostic entities, and the IAIHG scoring system should not be utilized to establish subgroups of patients.

In addition to the mentioned viewpoints, Czaja17 proposed that the diagnosis of overlap syndrome should be considered more as clinical descriptions rather than pathological entities, with the dominant component of the disease determining its classification and treatment.

Temporal dynamics of clinical manifestationsAIH and PBC may sometimes manifest concurrently, but frequently they unfold sequentially, or there might even be a change in phenotype over the course of the clinical history.

In this regard, Poupon et al.15 study – mentioned above – indicated that 4.3% of their PBC patients experienced the onset of AIH in an unpredictable manner, emphasizing the potential impact of AIH on the deterioration of liver function in those with PBC. Notably, the time lapse between the diagnosis of PBC and the diagnosis of AIH varied significantly, spanning from 6 months to 13 years.

Lohse A.W. et al.14 highlighted that PBC serves as the instigator of the autoimmune inflammatory disease process. Genetic susceptibility (the presence of HLA-B8, DR3 or DR4) plays a crucial role by allowing the progression of PBC to an inflammatory hepatitis, presenting with many or all features of AIH. Among the 20 patients studied, the data revealed that, except for one case, the characteristics of both PBC and AIH progressed in tandem. This synchronous progression was evident not only in clinical presentation but also in the response to immunosuppressive therapy.

These two works underscore the dynamic and evolving nature of these conditions, where the progression or alteration of symptoms and characteristics can significantly impact the overall clinical narrative.

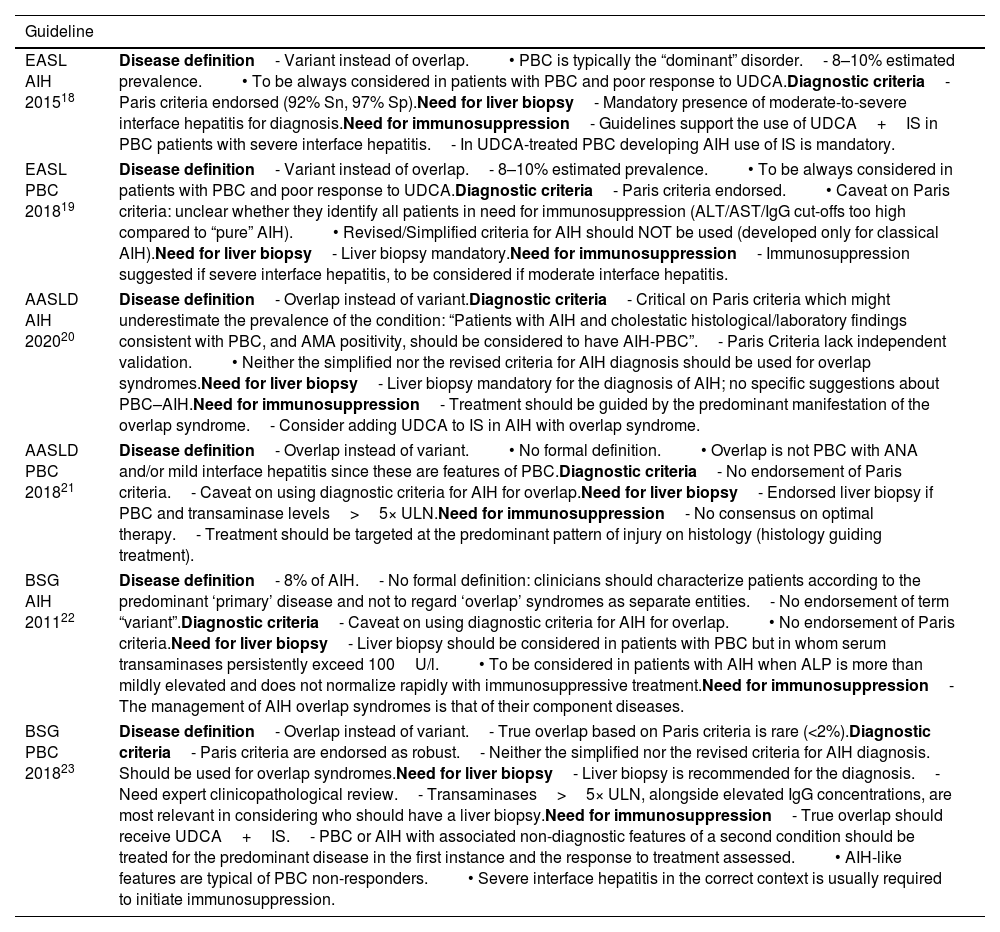

Disagreement among international guidelinesCurrently there is substantial disagreement about the diagnosis and management of PBC–AIH VS across international guidelines (Table 3). The Paris criteria are the only formal diagnostic criteria available in the literature; yet not all the guidelines endorse their use. Furthermore, liver biochemistry, serology status, and histology are assigned equal importance in these criteria, but this aspect is subject to debate. PBC inherently exhibits a continuous range of hepatitis, which suggests that rigid thresholds may not be suitable.

Main points of disagreement in international guidelines.

| Guideline | |

|---|---|

| EASL AIH 201518 | Disease definition- Variant instead of overlap.• PBC is typically the “dominant” disorder.- 8–10% estimated prevalence.• To be always considered in patients with PBC and poor response to UDCA.Diagnostic criteria- Paris criteria endorsed (92% Sn, 97% Sp).Need for liver biopsy- Mandatory presence of moderate-to-severe interface hepatitis for diagnosis.Need for immunosuppression- Guidelines support the use of UDCA+IS in PBC patients with severe interface hepatitis.- In UDCA-treated PBC developing AIH use of IS is mandatory. |

| EASL PBC 201819 | Disease definition- Variant instead of overlap.- 8–10% estimated prevalence.• To be always considered in patients with PBC and poor response to UDCA.Diagnostic criteria- Paris criteria endorsed.• Caveat on Paris criteria: unclear whether they identify all patients in need for immunosuppression (ALT/AST/IgG cut-offs too high compared to “pure” AIH).• Revised/Simplified criteria for AIH should NOT be used (developed only for classical AIH).Need for liver biopsy- Liver biopsy mandatory.Need for immunosuppression- Immunosuppression suggested if severe interface hepatitis, to be considered if moderate interface hepatitis. |

| AASLD AIH 202020 | Disease definition- Overlap instead of variant.Diagnostic criteria- Critical on Paris criteria which might underestimate the prevalence of the condition: “Patients with AIH and cholestatic histological/laboratory findings consistent with PBC, and AMA positivity, should be considered to have AIH-PBC”.- Paris Criteria lack independent validation.• Neither the simplified nor the revised criteria for AIH diagnosis should be used for overlap syndromes.Need for liver biopsy- Liver biopsy mandatory for the diagnosis of AIH; no specific suggestions about PBC–AIH.Need for immunosuppression- Treatment should be guided by the predominant manifestation of the overlap syndrome.- Consider adding UDCA to IS in AIH with overlap syndrome. |

| AASLD PBC 201821 | Disease definition- Overlap instead of variant.• No formal definition.• Overlap is not PBC with ANA and/or mild interface hepatitis since these are features of PBC.Diagnostic criteria- No endorsement of Paris criteria.- Caveat on using diagnostic criteria for AIH for overlap.Need for liver biopsy- Endorsed liver biopsy if PBC and transaminase levels>5× ULN.Need for immunosuppression- No consensus on optimal therapy.- Treatment should be targeted at the predominant pattern of injury on histology (histology guiding treatment). |

| BSG AIH 201122 | Disease definition- 8% of AIH.- No formal definition: clinicians should characterize patients according to the predominant ‘primary’ disease and not to regard ‘overlap’ syndromes as separate entities.- No endorsement of term “variant”.Diagnostic criteria- Caveat on using diagnostic criteria for AIH for overlap.• No endorsement of Paris criteria.Need for liver biopsy- Liver biopsy should be considered in patients with PBC but in whom serum transaminases persistently exceed 100U/l.• To be considered in patients with AIH when ALP is more than mildly elevated and does not normalize rapidly with immunosuppressive treatment.Need for immunosuppression- The management of AIH overlap syndromes is that of their component diseases. |

| BSG PBC 201823 | Disease definition- Overlap instead of variant.- True overlap based on Paris criteria is rare (<2%).Diagnostic criteria- Paris criteria are endorsed as robust.- Neither the simplified nor the revised criteria for AIH diagnosis. Should be used for overlap syndromes.Need for liver biopsy- Liver biopsy is recommended for the diagnosis.- Need expert clinicopathological review.- Transaminases>5× ULN, alongside elevated IgG concentrations, are most relevant in considering who should have a liver biopsy.Need for immunosuppression- True overlap should receive UDCA+IS.- PBC or AIH with associated non-diagnostic features of a second condition should be treated for the predominant disease in the first instance and the response to treatment assessed.• AIH-like features are typical of PBC non-responders.• Severe interface hepatitis in the correct context is usually required to initiate immunosuppression. |

According to the latest consensus24 liver biopsy remains the standard method for diagnosing AIH. Criteria to consider AIH likely are the presence of a predominantly portal lymphoplasmacytic hepatitis together with more than mild interface activity and/or more than mild lobular hepatitis, without histological features indicative of another liver disease. Similarly, AIH is considered likely in cases of predominantly lobular hepatitis with or without centrilobular necroinflammation, accompanied by at least one of the following features: portal lymphoplasmacytic hepatitis, interface hepatitis, or portal-based fibrosis, and in the absence of histological features suggestive of another liver disease. Emperipolesis and hepatocellular rosettes, once considered typical, were not deemed diagnostic in this Delphi round.

Florid bile duct lesion is believed to be a characteristic aspect of PBC, and ‘Chronic nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis’ was the descriptive term used to refer to the typical morphologic changes of bile ducts in PBC.25 However, while in active stages the bile duct destruction may be prominent, a wide range of reactive or senescent alterations, such as cytoplasmic vacuolization, irregular and hyperchromatic nuclei, or intensely eosinophilic cytoplasm in angulated or abortive ducts may indicate chronic cholangitis, the fundamental lesion of PBC.26,27 Starting from the 40 to 80μm caliber duct, the chronic stimulation finally leads to ductopenia, defined as the presence of bile ducts in less than 50% of portal tracts, with the contribution of a reduced supply of progenitor cells sited in canals of Hering that can be demonstrated with a Keratin 19 immunohistochemistry.28,29

As discussed in previous sections, atypical biochemical and serological profiles often need a pathologic assessment, frequently unveiling a complex histological picture that requires a careful assessment of lesions and a strict clinico-pathological correlation. Similarly, atypical histological patterns may, in patients with defined clinical/laboratory presentations, suggest the presence of underlying autoimmune processes with shared PBC–AIH features. Indeed, various grades of interface hepatitis can also be observed in approximately 25% of patients with PBC,30,16 while different levels of biliary injury may be seen in about 10–20% of patients with AIH.31

As stated by Portmann et al., a substantial number of patients show a variable grade of lymphocytic interface activity along with a highly active bile duct damage (i.e. florid duct lesion), suggesting an extension of the immunological process involving the bile duct system to adjacent hepatocytes.32 According to Chazouìlleres et al., however, in about 10% of cases, the interface process becomes dominant, suggesting the presence of a VS.7 The histological diagnostic criteria included in this work shaped the Paris criteria, which have been endorsed by EASL in 200933; however, different systems have been proposed and applied in different clinical scenarios, and the overall frequency of histologic VS is still under debate.9,34

Terracciano et al.35 conducted a retrospective study on 42 liver biopsy samples from 39 patients who met serologic and histologic criteria for autoimmune liver diseases. They identified 10 cases of VS, 10 of autoimmune cholangitis1 (AIC), 10 of PBC and 9 of AIH type 1. Their results include: (1) PBC and AIC exhibited more prominent granulomas and biliary duct lesions than VS and AIH, (2) bile duct loss was not observed in AIH cases, (3) VS and AIH showed a higher prevalence of hepatocellular damage features, such as piecemeal necrosis, spotty lobular necrosis and confluent necrosis, compared to PBC and AIC, (4) HLA-DR antigen expression by hepatocytes was more frequent in AIH and VS while its expression by the bile duct epithelium was more frequent in PBC and AIC. This study suggests that there exists a morphologic spectrum in autoimmune liver diseases, with PBC at one end, AIH at the other, VS in the middle (but closer clinically and histologically to AIH than to PBC), and AIC appearing as an AMA negative subtype of PBC.

These findings were further stressed by Kobayashi et al. that demonstrated how features like lobular hepatitis, hepatocytic rosettes, and emperipolesis are less frequent in severe PBC with interface hepatitis than those with classic AIH.36 However, it's crucial to note that the presence of histological findings resembling PBC-like bile duct injury in cases of classic AIH or lymphocytic interface hepatitis in cases of classical PBC alone does not suffice for diagnosing VS.32

In contrast, A.W. Lohse et al.14 elucidate that PBC seems to initiate the autoimmune inflammatory disease process, suggesting that the so-called VS is very likely to be a form of PBC that develops a more hepatitis picture in genetically susceptible individuals.

According to the authors’ study court, the age distribution provides additional validation for this hypothesis, as variant patients not only share a similar age range with PBC patients but also demonstrate an older age profile compared to individuals diagnosed with AIH.

Liang et al.37 examined biopsies from untreated patients with AIH, PBC and VS. They analyzed histologic features, fibrosis, and clinical data, including serology, autoantibodies, treatment, and prognosis. The results revealed significant differences in histologic features between AIH and PBC. Cases of VS were more likely to exhibit bile duct-centered processes, distinct from AIH, and interface-centered processes not seen in PBC. Specifically, VS cases displayed features reminiscent of PBC, including 100% prevalence of bile duct damage, a lower degree of inflammation gradient from bile duct to interface (29%), reduced plasma cell cluster (43%), and an absence of pericentral inflammation (0%), distinguishing them from AIH (p<0.05). However, they also presented features typical of AIH, such as 100% occurrence of ductular reaction, interface hepatitis, and 86% periportal fibrosis, which were not observed in PBC cases (p<0.05).

The complexity of the topic requires novel tools to advance our understanding. Artificial Intelligence (AI) emerges as a transformative force, capable of extracting meaningful predictions directly from liver slide images. Computational pathology (CPATH) is a branch of pathology focused on retrieving details from digitized pathology images and related metadata.38 This metadata may include patient demographics, annotations made by pathologists, or biochemical parameters. A fundamental technology within CPATH is Whole Slide Imaging (WSI), which entails converting glass slides into a digital format using a slide scanner. After the conversion to a digital format, the histological slide becomes accessible for remote viewing or analysis. Techniques such as Deep Learning (DL) are employed to analyze the digitized images, facilitating advanced image analysis. Remarkably, without human annotation, a DL algorithm proficiently could capture distinct features of both AIH and PBC. This approach holds promise in assisting physicians in distinguishing pure forms of AIH and PBC from VS, contributing to enhanced diagnostic precision.

Beyond histology: serological insights into PBC/AIHThe overlap in histological features between PBC and AIH mandates that the diagnosis of PBC–AIH syndrome is not based solely on the results of liver biopsy interpretation. At the serological level, autoantibody profiles differ significantly, since AIH is characterized by the prevalence of ANA and ASMA, whereas PBC is almost exclusively associated with AMA.

As regards AIH, patients may show positivity to anti-actin antibodies, antibodies targeting liver kidney microsome 1 (anti-LKM1), antibodies against liver cytosol antigen type 1 (anti-LC1), antibodies against soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas (anti-SLA/LP) and perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA), which are often the atypical peri-nuclear anti-neutrophil antibody (pANNA) variety.39 These antibodies are not found in “pure” PBC.

Regarding PBC, high titers of AMA are detected in approximately 95% of patients with PBC. Positive titers of ANA are present in at least one-third of cases. Antibodies against the nuclear pore membrane glycoprotein (anti-gp210) and nuclear protein sp100 (anti-sp100) are highly specific for PBC, with a specificity exceeding 95%.40 Yet, AMA-positive AIH is an existing entity and AIH patients with confirmed AMA positivity do not necessarily have or develop PBC over time.41

Nevertheless, also autoantibody signatures are not always clear-cut. For instance, it is important to stress that some individuals with all the features of AIH may maintain a persistent positive status for AMA: however, this alone does not necessarily imply a distinctive AIH/PBC VS. In this context, O’Brien et al.42 emphasize that 10% of patients who exhibit all the characteristics of AIH may also maintain a persistent positive AMA status. In a cohort study involving 15 AMA-positive AIH patients, none displayed any histological indicators suggestive of PBC. Furthermore, those individuals who received conventional steroid treatment didn’t display clinical or histological signs of PBC, even though AMA continued to be detected over a 27-year follow-up period.

Referring to the study conducted by Muratori et al.,43 anti-dsDNA antibodies were notably more prevalent in 15 cases of PBC–AIH VS (60%) compared to 120 cases of PBC (4%) and 120 cases of AIH (26%) patients (p<0.0001 and p<0.01 respectively). The concurrent presence of both AMA and anti-dsDNA was remarkably specific (98%) for the variant condition, observed in 47% of overlap cases, as opposed to only 2% in the control group. Additionally, differences in immunoreactivity to a distinct subset of AMA between patients with PBC and those with PBC–AIH VS have been suggested as potentially significant in distinguishing between these patient groups.44

Another interesting study was published by Himoto et al.45 and investigated the prevalence of anti-p53 antibodies in patients with autoimmune liver diseases, including AIH, PBC and VS. A total of 40 patients with AIH, 41 with PBC, 8 with PBC–AIH VS were enrolled. Among them, 15% of those with AIH and 50% of those with PBC–AIH VS tested positive for anti-p53. Only 2.4% of patients with PBC were positive for anti-p53. This indicates a significantly higher prevalence of anti-p53 in VS compared to PBC. The emergence of anti-p53 antibodies may serve as a valuable tool for distinguishing AIH or PBC–AIH VS from PBC and predicting favorable outcomes in AIH patients. However, it is important to note that this is a monocentric study which involves a small sample size: caution is advised and validation across diverse and larger cohorts is recommended.

The recent study published by Liang et al.37 found varying positivity rates for different antibodies in autoimmune liver diseases. ANA was positive in 81% of AIH cases, 60% in PBC cases, and 100% in VS, with no significant differences. ASMA was 100% positive in AIH and VS, significantly higher than 29% in PBC. AMA positivity was 78% in PBC and 86% in VS, significantly higher than 13% in AIH. The authors also explored the correlation between autoantibodies and morphological features that differentiate AIH and PBC. Notably, cases manifesting interface hepatitis demonstrated a significantly higher percentage of ASMA positivity compared to those lacking these features. Similarly, instances with bile duct damage (including ductopenia) and granulomas were more likely to exhibit AMA positivity than cases without these specific features. While autoantibodies provide valuable diagnostic information, Liang et al.’s study emphasizes the correlation between autoantibodies and morphological features, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the immunological and histological aspects that differentiate AIH and PBC.

Distinct serological profiles in patients identified as potential variant syndromes could lend support to the notion that these conditions are unique disease entities.16 However, we believe that these findings do not inherently signify a distinct disease. Instead, we advocate for adopting a dynamic perspective over time, closely observing the natural history of these conditions, and being prepared to adjust the label if necessary. In this light, patients may display uncommon antibodies without necessarily being distinct from those with AIH or PBC.

The evolving understanding of serological and histological markers contributes to a more nuanced approach in diagnosing and characterizing autoimmune liver diseases, challenging conventional classifications, and paving the way for improved diagnostic accuracy and tailored treatment strategies.

Immunosuppression: who to treat?Identifying PBC–AIH VS is pivotal due to its elevated risk of complications and a higher likelihood of septic shock when compared to AIH or PBC in isolation. The absence of standardized diagnostic criteria and treatment guidelines has led to varied groups of patients, a range of treatment approaches and inconsistent outcomes in different experiences.

Especially concerning the therapy, Albert J. Czaja emphasizes the importance of distinguishing between patients who have AIH with cholestatic characteristics and those with cholestatic disease showing features of AIH.46 Together with his colleagues,5 the author reported that individuals with PBC–AIH VS achieved remission with corticosteroid treatment at a similar rate as those with confirmed AIH (75% vs 64%) if the cholestatic characteristics of PBC are mild.

Treatments and outcomes have differed in individuals primarily exhibiting the PBC phenotype.46 These patients have shown various responses to UDCA therapy alone (typically at a dose of 13–15mg/kg daily). In cases where patients predominantly have PBC with secondary features of AIH, treatment with UDCA alone has often proven insufficient in preventing the development of frequent complications such as portal hypertension, esophageal varices, gastrointestinal bleeding, ascites and the risk of hepatic failure or the need for a liver transplant.47,48 Consequently, combination therapies have frequently been administered to these patients.

Kuiper et al.11 discovered a 10-year survival rate of 92% among patients with the VS. One plausible reason for this positive prognosis might be the systematic application of a combined treatment involving UDCA and immunosuppressive therapy.49

Joshi and colleagues’ study50 also focuses on the advantages of corticosteroids in the context of patients with both PBC and AIH features. For individuals diagnosed with PBC who also exhibit additional AIH characteristics, it has been proposed that the preferred treatment option might involve a combination of UDCA and corticosteroids.

Another study held by Tanaka et al.51 wanted to propose a rationale for using combination treatment for PBC–AIH VS. This study enrolled 33 patients with VS, 89 patients with PBC and 44 patients with AIH alone as control groups. Over an average follow-up period of 6.1 years, liver histology indicated a significantly higher hepatitis activity compared to the cholangitis activity score (p<0.001). By the end of the follow-up period, corticosteroids were used in 23 patients (72%) and no liver-related deaths or liver transplantations were reported. The primary factors influencing the response to standard corticosteroid therapy were the severity of the AIH component, evaluated using the simplified scoring system of the IAIHG, and the extent of the cholestatic component's weakness, determined by the serum alkaline phosphatase level.52

According to Boberg et al.,16 for patients exhibiting predominantly cholestatic indications favoring a PBC diagnosis, UDCA should be the primary treatment option. In cases of PBC accompanied by AIH characteristics, UDCA alone can lead to improvement, but incorporating immunosuppressive drugs may enhance the treatment's effectiveness.

We are aware that current criteria for identifying variant syndromes are stringent, which may result in some patients being overlooked. For this reason, it is crucial to initially address the primary disease. Following this, each patient should be individually assessed for any variant syndromes, and their treatment plans should be adjusted accordingly.

Therefore, we recommend that, except in cases of Paris criteria where AIH is clearly present, UDCA should be initiated, and after 3–6 months, it should be assessed whether to introduce immunosuppression. Of course, if there are urgency criteria, treatment should commence immediately, likely falling into the first case and continued based on the biochemical response.

ConclusionsThe presence of overlapping features between PBC and AIH is a matter of fact and occurs in a variable proportion of cases that it is difficult to quantify due to poor homogeneity in definition of cases in the available literature. True “overlap” is considered a condition quite rare and typically can be diagnosed by the use of Paris Criteria; conversely, some features, either at the histological or the serological level, that are considered more specific of one or the other condition can occur much more frequently without an immediate consequence in term of diagnosis, prognosis and treatment approach. The approach to these “variant” syndromes should be cautious to avoid harmful overtreatment, especially when AIH-features are suspected in PBC cases. Yet, the availability of second- and third-line therapies in the near future may pose clinical challenges also in cases of AIH with biliary abnormalities, since newer drugs do not necessarily have the safety of UDCA. Histology represents a core element in the evaluation of variant syndromes, but could be a double-edged sword, leading to misinterpretations if handled without care. Thus, it is better that patients with suspected overlap/variant syndromes are referred to expert centers equipped with the adequate multidisciplinary expertise. However, even in these centers patients may be misdiagnosed and mistreated. The main issue resides in the disagreement among experts, as proven by the heterogenous and somehow divergent recommendations in international guidelines available on the topic. We believe that times are mature for a consensus that reconciles different points of views to help moving forward the field. In addition, it is always important that clinicians have a dynamic view on these conditions, since different features may appear over time, forcing to reconsider the original diagnostic labels.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Methods: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, UpToDate and Google Scholar databases were queried without temporal constraints up to January 2024.

Autoimmune cholangitis, currently known as ‘AMA-negative PBC,’ is characterized by cases that closely resemble PBC in clinical, histological, and biochemical aspects, except for the absence of detectable antimitochondrial antibodies. Serum ANA and anti-SMA may be present in high titers. This condition is classified as an ‘outlier syndrome’ due to its similarity to PBC, with the key distinction being the autoantibody profile.13