To investigate hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence, risk factors and the performance of baseline REACH-B risk score in a Portuguese chronic hepatitis B (CHB) population on antiviral therapy.

MethodsRetrospective study of CHB patients who were treated with tenofovir or entecavir for at least 12 months. Multivariate analysis was performed to identify factors associated with HCC. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of HCC at 1, 3 and 5 years on therapy. The performance of the REACH-B score at baseline was assessed.

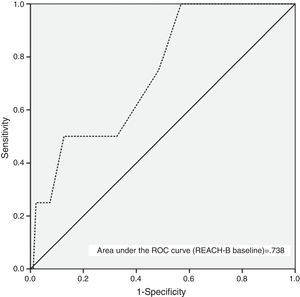

ResultsOne hundred and twenty patients initiated nucleos(t)ide analogs (NUC) therapy (age, 47±14 years-old; 83 male; 11% had cirrhosis; 71% tenofovir; 73% HBeAg-negative; 61% treatment-naïve). After a median time under NUC of 39 months, 9 patients (7.5%) developed HCC. The calculated cumulative incidence rates of HCC at 1, 3 and 5 years on therapy were 5.1%, 7.3% and 8.8%, respectively. Independent predictors for HCC occurrence: age and cirrhosis at baseline. Diagnostic accuracy of baseline REACH-B score in predicting HCC development: AUC 0.738, 95%CI: 0.521–0.955. The cutoff value of 8 points had a sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of 75%, 52%, 6% and 98%, respectively in predicting HCC occurrence during therapy.

ConclusionsOlder age and cirrhosis at baseline were independent predictors for HCC development. Discriminatory performance of baseline REACH-B score was limited.

Estudar a incidência de carcinoma hepatocelular (CHC), factores de risco e desempenho do score REACH-B (basal) numa população portuguesa de doentes com infecção crónica pelo vírus da hepatite B (VHB) sob análogos dos nucleós(t)idos de 3ª geração (NUC).

MétodosEstudo retrospetivo de uma coorte de doentes com infecção crónica pelo VHB tratados com tenofovir ou entecavir durante pelo menos 12 meses. Foi realizada uma análise multivariada para identificar os factores associados ao desenvolvimento de CHC. Através do método de Kaplan-Meier foi estimada a incidência cumulativa de CHC ao final de 1, 3 e 5 anos sob terapêutica antiviral.

ResultadosCento e vinte doentes iniciaram terapêutica com um NUC (idade, 47±14 anos; 83 género masculino; 11% com cirrose; 71% tenofovir; 73% AgHBe-negativo; 61% naïves). Após um período mediano de 39 meses sob NUC, 9 doentes (7.5%) desenvolveram CHC. A incidência cumulativa de CHC ao final de 1, 3 e 5 anos sob terapêutica antiviral foi de 5,1%, 7,3% e 8,8%, respetivamente. Preditores independentes de CHC: idade e cirrose diagnosticada previamente ao início da terapêutica antiviral. Precisão diagnóstica da aplicação basal do score REACH-B para predizer CHC: AUC 0,738, 95%CI: 0,521-0,955. A utilização do valor cutoff de 8 pontos produziu uma sensibilidade, especificidade, valor preditivo positivo e valor preditivo negativo de 75%, 52%, 6% e 98%, respetivamente na predição de ocorrência de CHC durante o tratamento.

ConclusõesIdade avançada e a presença de cirrose diagnosticada previamente ao início da terapêutica antiviral demonstraram-se preditores independentes para o desenvolvimento de CHC. O poder discriminatório basal do score REACH-B foi limitado.

It is believed that persistent viral replication together with the resulting liver injury are key risk factors for hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).1,2 Additionally, important viral and host-related factors (genotype, HBV mutants, high HBV viral load, serum hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg] levels, older age, male gender, excessive alcohol intake and possibly metabolic syndrome) may affect the risk of HCC development.3–5 Long-term therapy with nucleos(t)ide analogs (NUC) has improved the overall outcome of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and resulted in a significant reduction in the need for liver transplantation.6 Treatment with the third generation NUCs (entecavir and tenofovir) causes complete suppression of viral replication in more than 95% of the patients, with increased rates of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion (in HBeAg positive patients) and improved liver histology including reversal of histological cirrhosis in most cases.7–11 However, antiviral therapy reduces but does not eliminate the risk of HCC in CHB patients with or without cirrhosis. In fact, evidence of the effect of antiviral therapy on clinical outcomes including HCC related-incidence and mortality is weak, as demonstrated in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.12 Most of the published data about the effect of NUCs on HCC risk are derived from older prospective cohort and case–control studies using lamivudine or interferon. Regarding high-genetic barrier NUCs, most of the available data involve patients treated with entecavir (ETV), with initial reports regarding the effect of ETV being reported by Lampertico et al.13 This Italian study demonstrated that CHB patients with compensated cirrhosis and a persistently undetectable serum HBV DNA during 5 years of ETV monotherapy had an annual rate of HCC incidence of 2.5%, which is almost the same risk that had been reported in untreated HBeAg-negative European patients. Retrospective and prospective observational cohort studies that provide HCC data for CHB patients mainly treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) are lacking. Until recently, the limited data on the risk of HCC following the treatment of CHB patients with TDF were obtained from the roll over study of registration trials in HBeAg-positive (GS-US-174-0103) and HBeAg-negative (GS-US-174-0102) patients.14 Buti et al. reported that the incidence of HCC in 152 patients with cirrhosis and 482 with CHB treated with TDF for 5 years was only 3.3% and 1.5%, respectively (annual incidence: 0.7%).15 Two recent studies,14,16 found that TDF reduced HCC incidence compared to the predicted HCC risk using the Risk Estimation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B (REACH-B) calculator.

We performed a real-life single-center retrospective observational cohort study of 120 CHB Portuguese patients mainly treated with TDF. Univariate and multivariate analysis (Cox proportional hazards regression) of risk factors associated with HCC development were performed. Accuracy of a HCC-risk score (REACH-B) at baseline was assessed.17,18

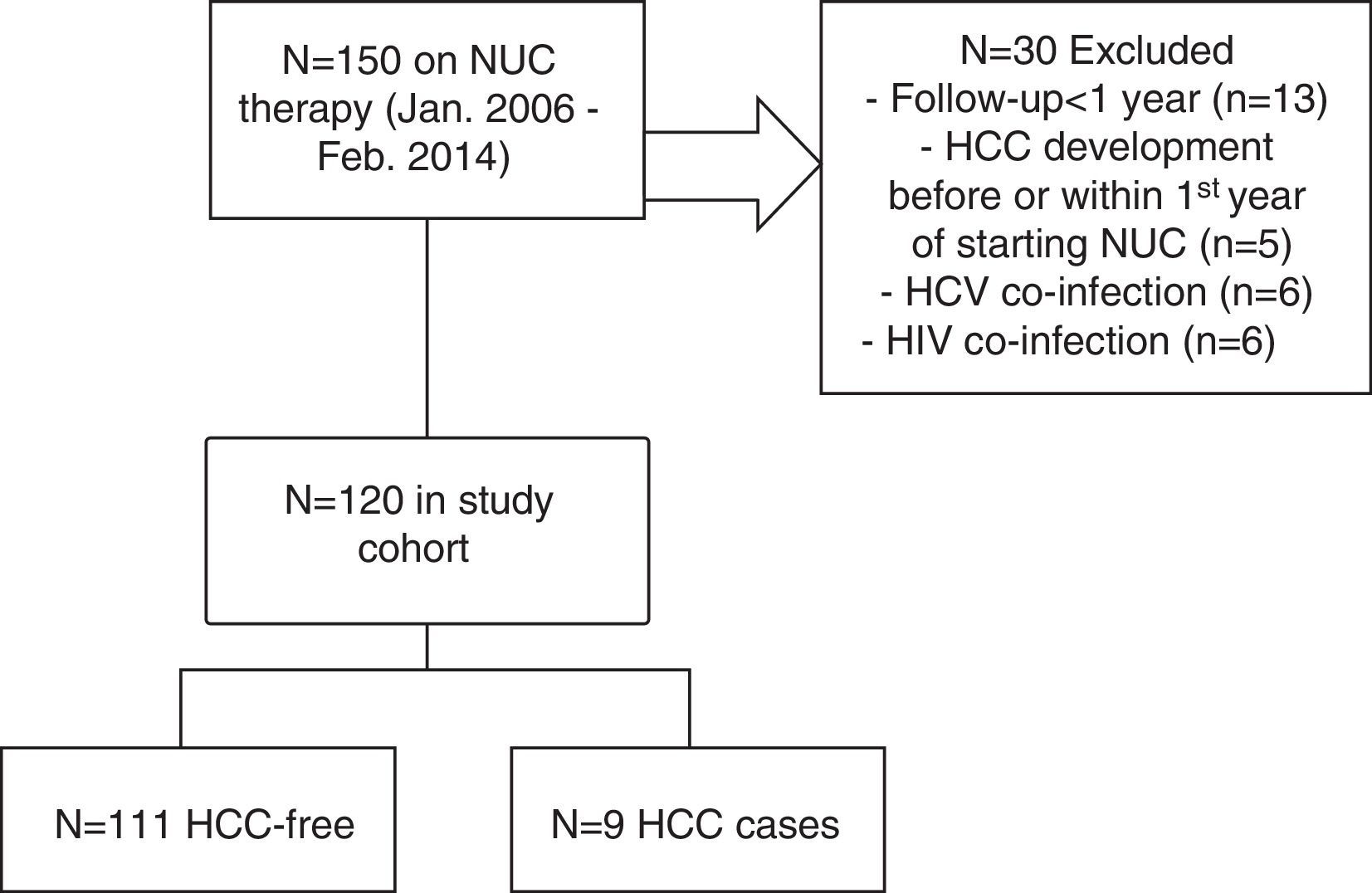

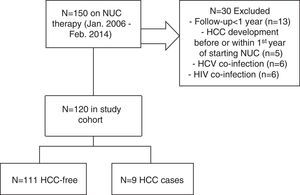

2Patients and methods2.1Study population, clinical and laboratory evaluationWe included consecutive patients with CHB who were treated with tenofovir or entecavir for at least 12 months in Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Ocidental (Hospital Egas Moniz, Hospital Santa Cruz and Hospital São Francisco Xavier) – a tertiary referral center (catchment population ∼993000 individuals) – from January 2006 to February 2014. All patients had a positive HBsAg for at least 6 months. Exclusion criteria were as follows: less than 12 months on NUC therapy (n=13), pre-existing HCC or HCC diagnosed within the first year of NUC therapy (n=5), coinfection with hepatitis D virus, hepatitis C virus (n=6) and/or human immunodeficiency virus (n=6) – see Fig. 1 for flow-chart of study cases selection. Data were collected retrospectively from the medical records, either on paper or electronic charts. HBV DNA was measured by TaqMan (Roche Diagnostics) real-time polymerase chain reaction assay with a linear range of detection from 20 to 1.7×108IU/mL. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) serum levels were measured biannually, normal range for our laboratory is between 21 and 72U/L. Patients were retrospectively followed since CHB diagnosis until the end of follow-up or HCC occurrence (duration of follow-up) and since NUC therapy start until the end of follow-up or HCC occurrence (time on NUC therapy). Cirrhosis was defined by ultrasonographic findings (shrunken small liver with a nodular surface), clinical and laboratorial findings compatible with portal hypertension (e.g., ascites, splenomegaly, gastroesophageal varices, thrombocytopenia). Cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients with clearly defined risk factors (such as, African patients over 20 year-old, Asian male patients over 40 years-old or female over 50 years-old, patients with family history of HCC) were followed by abdominal ultrasound and serum measurement of alfa-phetoprotein every 6 months, as recommended by guidelines.19 Excessive alcohol intake was defined as a daily intake of >25g/alcohol. Total virological response was defined as undetectable HBV DNA at 3 or 6 months under antiviral therapy. Partial virological response was defined as a decrease in HBV DNA level of more than 1log10IU/mL (but still detectable) after 6 months of therapy. Biochemical response was defined as normalization of ALT levels at any time during follow-up. The REACH-B score consists of five parameters: gender, age, ALT level, HBeAg status and HBV DNA level; it ranges from 0 to 17 points.17 After exclusion of baseline cirrhotic patients, REACH-B score was calculated at baseline, when patients began treatment. Cutoff values of 8 and 12 points were used to predict risks of HCC. The primary outcome of this study was HCC occurrence as defined by international societies guidelines.19 Approval for this study was obtained from our institutional ethics committee – Comissão de Ética para a Saúde, Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Ocidental (complying with the Treaty of Helsinki). All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

2.2Statistical analysesStatistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range) as appropriate. Qualitative and quantitative differences between subgroups were analyzed using χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical parameters and Student t test or Mann–Whitney test for continuous parameters as appropriate. In order to achieve a comprehensive analysis, subgroup comparisons were performed. Univariate and multivariate analysis by Cox proportional hazards regression model was performed to identify factors associated with HCC. After univariate analysis, variables with a p<0.05 entered in the multivariate analysis. Effect sizes are expressed as hazard ratios (HRs), adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of HCC at 1, 3 and 5 years on therapy and differences between factors were evaluated by the log-rank test. To assess the performance of the cutoff values for REACH-B score at baseline, we used the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of the different cutoff values for predicting HCC were estimated and reported. All statistical tests were two sided. Statistical significance was taken as p<0.05.

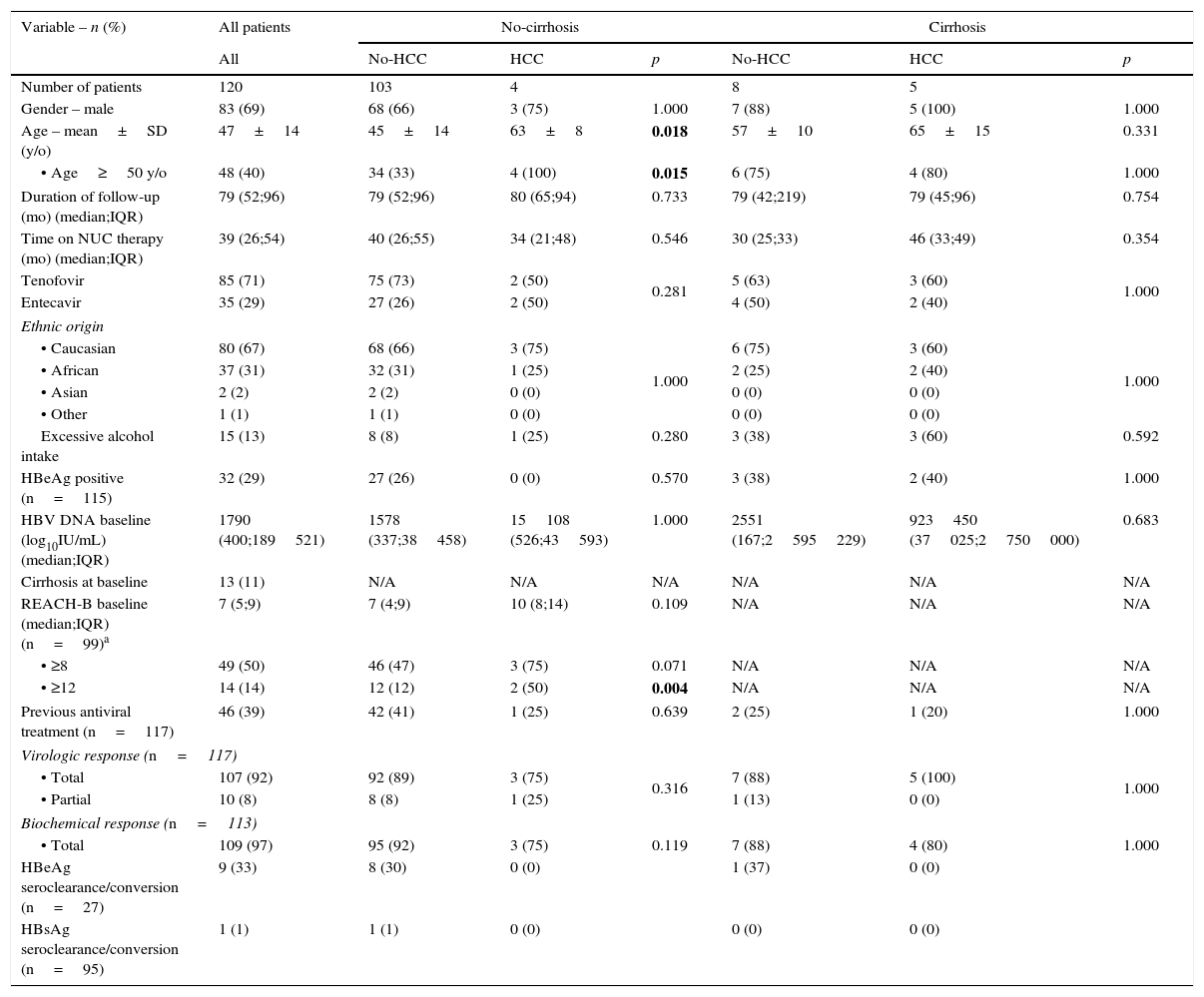

3Results3.1Patients’ characteristicsA summary of baseline epidemiological, clinical and laboratorial data of our cohort population is presented in Table 1. We identified 120 eligible CHB patients (mean age: 47±14 years-old; 83 male; 80 Caucasian; 32 HBeAg-positive). The median duration of follow-up and time on NUC therapy was 79 months (interquartile: 52–96) and 39 months (interquartile range: 26–54), respectively. A total of 13 patients (11%) had a baseline diagnosis of cirrhosis. Patients with cirrhosis were predominantly male (p=0.060), older (p=0.002) and had a higher prevalence of excessive alcohol intake (p=0.001). Study samples (cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic) were matched regarding duration of follow-up, time on NUC therapy and chosen NUC, previous antiviral therapy, ethnic origin, HBeAg positivity, HBV DNA viral load at baseline, biochemical and virological response. The majority of our population was treated with tenofovir (n=85; 71%). Seventy-one out of 117 (61%) of the patients were previously treatment-naïve. At the end of follow-up, 9 out of 27 (33%) HBeAg-positive patients had a serological response (HBeAg seroclearance/seroconversion) and one patient demonstrated HBsAg seroclearance/seroconversion.

Subgroup comparison between non-cirrhotic versus cirrhotic CHB patients on antiviral therapy regarding baseline characteristics and HCC prevalence.

| Variable – n (%) | All patients | No-cirrhosis | Cirrhosis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | No-HCC | HCC | p | No-HCC | HCC | p | |

| Number of patients | 120 | 103 | 4 | 8 | 5 | ||

| Gender – male | 83 (69) | 68 (66) | 3 (75) | 1.000 | 7 (88) | 5 (100) | 1.000 |

| Age – mean±SD (y/o) | 47±14 | 45±14 | 63±8 | 0.018 | 57±10 | 65±15 | 0.331 |

| • Age≥50 y/o | 48 (40) | 34 (33) | 4 (100) | 0.015 | 6 (75) | 4 (80) | 1.000 |

| Duration of follow-up (mo) (median;IQR) | 79 (52;96) | 79 (52;96) | 80 (65;94) | 0.733 | 79 (42;219) | 79 (45;96) | 0.754 |

| Time on NUC therapy (mo) (median;IQR) | 39 (26;54) | 40 (26;55) | 34 (21;48) | 0.546 | 30 (25;33) | 46 (33;49) | 0.354 |

| Tenofovir | 85 (71) | 75 (73) | 2 (50) | 0.281 | 5 (63) | 3 (60) | 1.000 |

| Entecavir | 35 (29) | 27 (26) | 2 (50) | 4 (50) | 2 (40) | ||

| Ethnic origin | |||||||

| • Caucasian | 80 (67) | 68 (66) | 3 (75) | 1.000 | 6 (75) | 3 (60) | 1.000 |

| • African | 37 (31) | 32 (31) | 1 (25) | 2 (25) | 2 (40) | ||

| • Asian | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| • Other | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Excessive alcohol intake | 15 (13) | 8 (8) | 1 (25) | 0.280 | 3 (38) | 3 (60) | 0.592 |

| HBeAg positive (n=115) | 32 (29) | 27 (26) | 0 (0) | 0.570 | 3 (38) | 2 (40) | 1.000 |

| HBV DNA baseline (log10IU/mL) (median;IQR) | 1790 (400;189521) | 1578 (337;38458) | 15108 (526;43593) | 1.000 | 2551 (167;2595229) | 923450 (37025;2750000) | 0.683 |

| Cirrhosis at baseline | 13 (11) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| REACH-B baseline (median;IQR) (n=99)a | 7 (5;9) | 7 (4;9) | 10 (8;14) | 0.109 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| • ≥8 | 49 (50) | 46 (47) | 3 (75) | 0.071 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| • ≥12 | 14 (14) | 12 (12) | 2 (50) | 0.004 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Previous antiviral treatment (n=117) | 46 (39) | 42 (41) | 1 (25) | 0.639 | 2 (25) | 1 (20) | 1.000 |

| Virologic response (n=117) | |||||||

| • Total | 107 (92) | 92 (89) | 3 (75) | 0.316 | 7 (88) | 5 (100) | 1.000 |

| • Partial | 10 (8) | 8 (8) | 1 (25) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | ||

| Biochemical response (n=113) | |||||||

| • Total | 109 (97) | 95 (92) | 3 (75) | 0.119 | 7 (88) | 4 (80) | 1.000 |

| HBeAg seroclearance/conversion (n=27) | 9 (33) | 8 (30) | 0 (0) | 1 (37) | 0 (0) | ||

| HBsAg seroclearance/conversion (n=95) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

Abbreviations: CHB, chronic hepatitis B; NUC, nucleos(t)ide analog therapy; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; SD, standard-deviation; y/o, years-old; mo, months; IQR, interquartile range; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; N/A, non-applicable; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

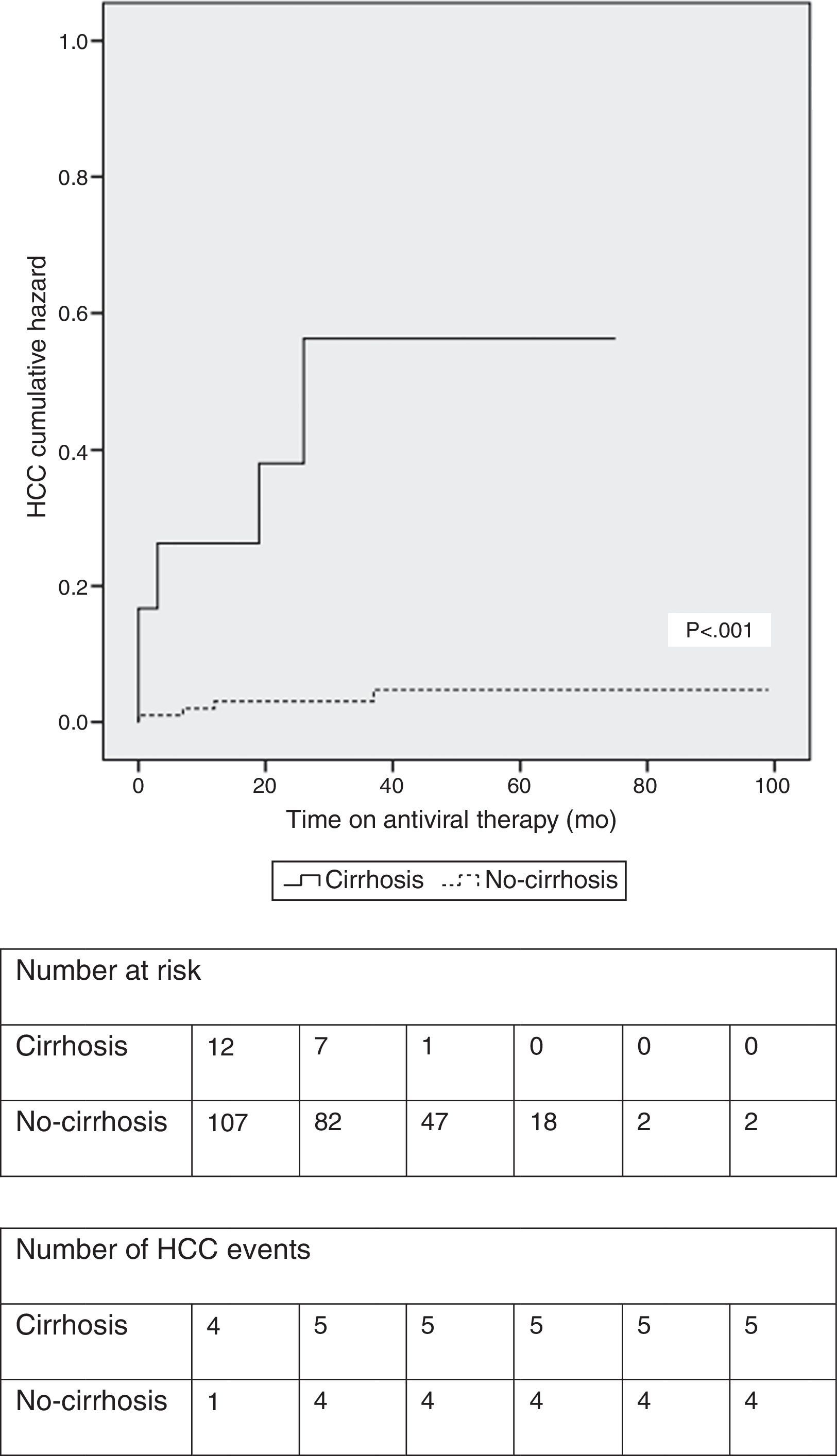

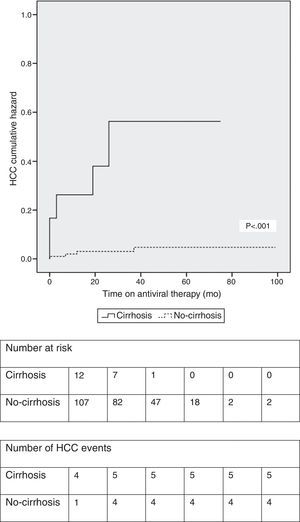

At a median treatment duration of 39 months (∼3.3 years), nine patients (7.5%) developed HCC. A slight majority of patients (five out of nine patients; 56%) who developed HCC had underlying cirrhosis at baseline. The calculated cumulative incidence rates of HCC at 1, 3 and 5 years on NUC therapy were 5.1%, 7.3% and 8.8%, respectively, in the entire cohort. The cumulative incidence of HCC was significantly higher in patients with cirrhosis at baseline (Fig. 2). In the subgroup of patients without baseline cirrhosis, the cumulative incidence rates of HCC at 1, 3 and 5 years were 3.0%, 3.0% and 4.6%, respectively; in the subgroup of patients with baseline cirrhosis, the cumulative rates were 23.1%, 43% and 43%, respectively.

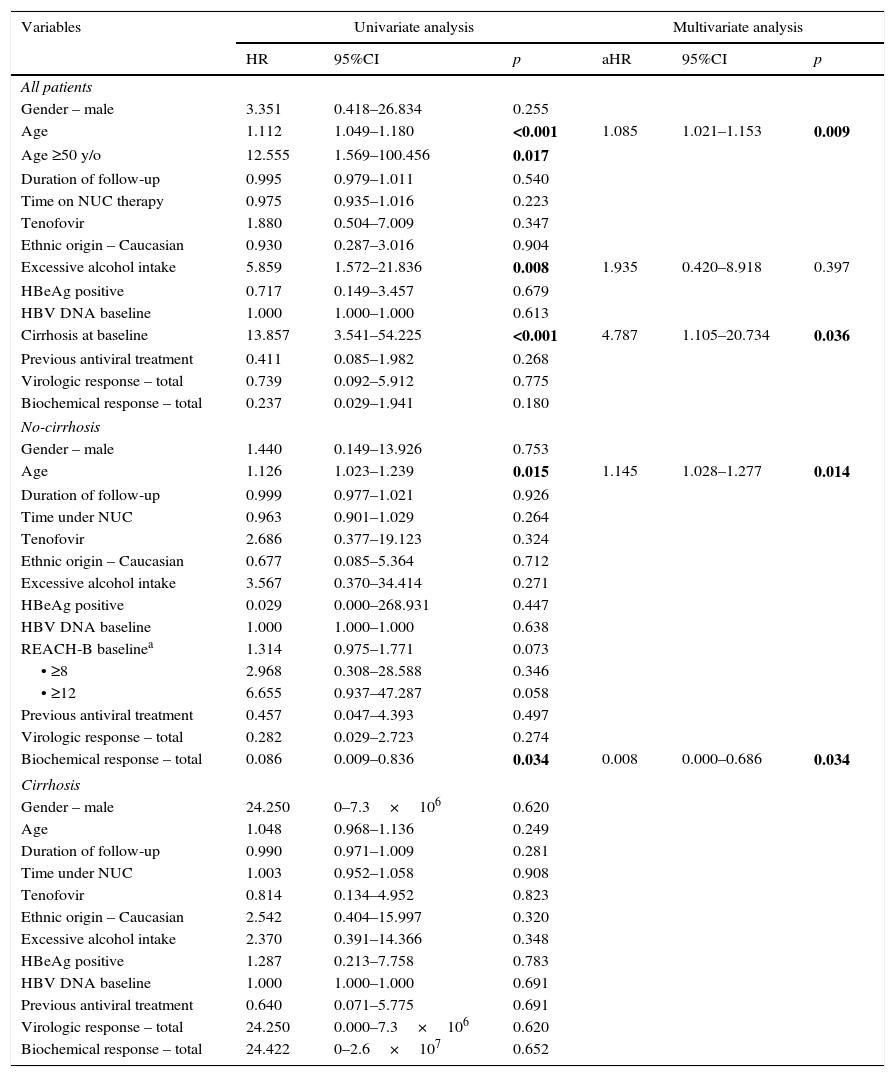

3.3Factors associated with HCC developmentPatients who developed HCC were older (64±12 vs 46±14; p=0.002), had higher prevalence of excessive alcohol intake (44% vs 10%; p=0.015), higher prevalence of cirrhosis at baseline (56% vs 7%; p=0.001) and higher REACH-B scores at baseline (median 12 points vs 8 points; p=0.002) (Table 1). On univariate analysis, age, excessive alcohol intake and cirrhosis at baseline were associated with subsequent development of HCC as seen in Table 2. On multivariate analysis, after adjusting for gender and time on NUC therapy, age (aHR: 1.085; 95%CI: 1.021–1.153; p=0.009) and cirrhosis at baseline (aHR: 13.857; 95%CI: 1.105–20.734; p=0.036) were independent predictors for HCC occurrence. Among the non-cirrhotic subgroup (Table 1), patients who developed HCC were older (63±8 vs 45±14; p=0.018). On univariate and multivariate analysis (Table 2), age and a lack of biochemical response to antiviral therapy were associated with HCC occurrence. In the cirrhotic subgroup, there were no risk factors for HCC occurrence.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with HCC in CHB patients on antiviral therapy.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | p | aHR | 95%CI | p | |

| All patients | ||||||

| Gender – male | 3.351 | 0.418–26.834 | 0.255 | |||

| Age | 1.112 | 1.049–1.180 | <0.001 | 1.085 | 1.021–1.153 | 0.009 |

| Age ≥50 y/o | 12.555 | 1.569–100.456 | 0.017 | |||

| Duration of follow-up | 0.995 | 0.979–1.011 | 0.540 | |||

| Time on NUC therapy | 0.975 | 0.935–1.016 | 0.223 | |||

| Tenofovir | 1.880 | 0.504–7.009 | 0.347 | |||

| Ethnic origin – Caucasian | 0.930 | 0.287–3.016 | 0.904 | |||

| Excessive alcohol intake | 5.859 | 1.572–21.836 | 0.008 | 1.935 | 0.420–8.918 | 0.397 |

| HBeAg positive | 0.717 | 0.149–3.457 | 0.679 | |||

| HBV DNA baseline | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.613 | |||

| Cirrhosis at baseline | 13.857 | 3.541–54.225 | <0.001 | 4.787 | 1.105–20.734 | 0.036 |

| Previous antiviral treatment | 0.411 | 0.085–1.982 | 0.268 | |||

| Virologic response – total | 0.739 | 0.092–5.912 | 0.775 | |||

| Biochemical response – total | 0.237 | 0.029–1.941 | 0.180 | |||

| No-cirrhosis | ||||||

| Gender – male | 1.440 | 0.149–13.926 | 0.753 | |||

| Age | 1.126 | 1.023–1.239 | 0.015 | 1.145 | 1.028–1.277 | 0.014 |

| Duration of follow-up | 0.999 | 0.977–1.021 | 0.926 | |||

| Time under NUC | 0.963 | 0.901–1.029 | 0.264 | |||

| Tenofovir | 2.686 | 0.377–19.123 | 0.324 | |||

| Ethnic origin – Caucasian | 0.677 | 0.085–5.364 | 0.712 | |||

| Excessive alcohol intake | 3.567 | 0.370–34.414 | 0.271 | |||

| HBeAg positive | 0.029 | 0.000–268.931 | 0.447 | |||

| HBV DNA baseline | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.638 | |||

| REACH-B baselinea | 1.314 | 0.975–1.771 | 0.073 | |||

| • ≥8 | 2.968 | 0.308–28.588 | 0.346 | |||

| • ≥12 | 6.655 | 0.937–47.287 | 0.058 | |||

| Previous antiviral treatment | 0.457 | 0.047–4.393 | 0.497 | |||

| Virologic response – total | 0.282 | 0.029–2.723 | 0.274 | |||

| Biochemical response – total | 0.086 | 0.009–0.836 | 0.034 | 0.008 | 0.000–0.686 | 0.034 |

| Cirrhosis | ||||||

| Gender – male | 24.250 | 0–7.3×106 | 0.620 | |||

| Age | 1.048 | 0.968–1.136 | 0.249 | |||

| Duration of follow-up | 0.990 | 0.971–1.009 | 0.281 | |||

| Time under NUC | 1.003 | 0.952–1.058 | 0.908 | |||

| Tenofovir | 0.814 | 0.134–4.952 | 0.823 | |||

| Ethnic origin – Caucasian | 2.542 | 0.404–15.997 | 0.320 | |||

| Excessive alcohol intake | 2.370 | 0.391–14.366 | 0.348 | |||

| HBeAg positive | 1.287 | 0.213–7.758 | 0.783 | |||

| HBV DNA baseline | 1.000 | 1.000–1.000 | 0.691 | |||

| Previous antiviral treatment | 0.640 | 0.071–5.775 | 0.691 | |||

| Virologic response – total | 24.250 | 0.000–7.3×106 | 0.620 | |||

| Biochemical response – total | 24.422 | 0–2.6×107 | 0.652 | |||

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; HR, hazard ratio; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio – adjusted for gender and time under NUC; CI, confidence interval; y/o, years-old; NUC, nucleos(t)ide analog therapy; HBeAg=Hepatitis B e antigen;

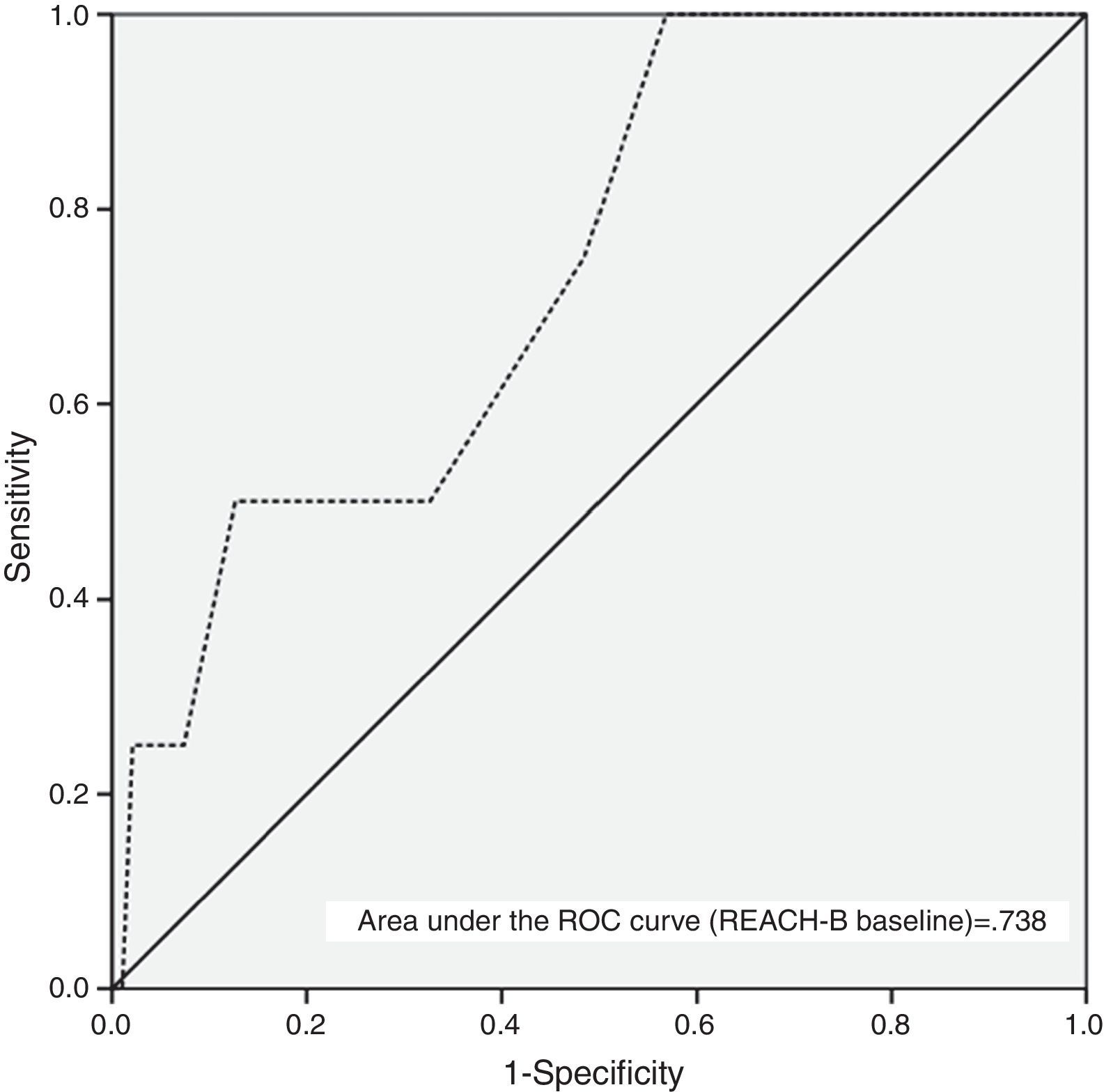

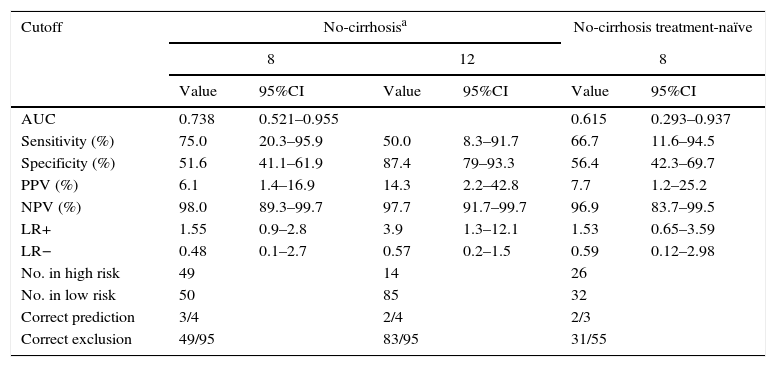

Table 3 and Fig. 3 show the AUC and diagnostic performance of baseline REACH-B score for HCC prediction among the non-cirrhotic population (n=107). The AUC was 0.738 (95%CI: 0.521–0.955) for REACH-B score at baseline. At a cutoff value of 8 points, the REACH-B score had 75% sensitivity (three of four HCCs identified) and 51.6% specificity (49 of 95 patients without HCC classified in the low-risk group) to predict HCC during the follow-up period. In the subgroup of non-cirrhotic population previously treatment-naïve (n=58), the obtained AUC was 0.615 (95%CI: 0.293–0.937).

AUC and diagnostic performance of baseline REACH-B score for HCC in CHB patients on antiviral therapy.

| Cutoff | No-cirrhosisa | No-cirrhosis treatment-naïve | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 12 | 8 | ||||

| Value | 95%CI | Value | 95%CI | Value | 95%CI | |

| AUC | 0.738 | 0.521–0.955 | 0.615 | 0.293–0.937 | ||

| Sensitivity (%) | 75.0 | 20.3–95.9 | 50.0 | 8.3–91.7 | 66.7 | 11.6–94.5 |

| Specificity (%) | 51.6 | 41.1–61.9 | 87.4 | 79–93.3 | 56.4 | 42.3–69.7 |

| PPV (%) | 6.1 | 1.4–16.9 | 14.3 | 2.2–42.8 | 7.7 | 1.2–25.2 |

| NPV (%) | 98.0 | 89.3–99.7 | 97.7 | 91.7–99.7 | 96.9 | 83.7–99.5 |

| LR+ | 1.55 | 0.9–2.8 | 3.9 | 1.3–12.1 | 1.53 | 0.65–3.59 |

| LR− | 0.48 | 0.1–2.7 | 0.57 | 0.2–1.5 | 0.59 | 0.12–2.98 |

| No. in high risk | 49 | 14 | 26 | |||

| No. in low risk | 50 | 85 | 32 | |||

| Correct prediction | 3/4 | 2/4 | 2/3 | |||

| Correct exclusion | 49/95 | 83/95 | 31/55 | |||

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the ROC curve; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; CI, confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR−, negative likelihood ratio.

Chronic hepatitis B is a major cause of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide, being responsible for 1 million deaths per year.20 The risk of CHB progression to HCC, albeit not being totally eliminated, might be reduced by antiviral therapy,21 therefore, the identification and classification of patients who are at increased risk of developing HCC is important. Several HBV risk scores have been published so far.22–25 The REACH-B (Risk Estimation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B) score is a simple score, involving non-invasive parameters and has been externally validated.17 It is useful to assess the long-term risk of HCC development at 3, 5 and 10 years of follow-up. This risk-prediction score was derived from the community-based Taiwanese REVEAL-HBV study (a cohort of 3584 patients) without cirrhosis and no antiviral treatment. Later, Wong et al. demonstrated that REACH-B score maintained its predictive power in patients on antiviral therapy.18

In the present study, we aimed to assess HCC incidence, risk factors and the performance of REACH-B in predicting HCC development in a Portuguese population (107 patients without cirrhosis) with CHB treated with NUCs (71% with TDF). The estimated prevalence of this infection in the Portuguese population is approximately 1%, which is relatively low,26,27 however, there is no doubt that HCC incidence in Portugal is on the rise and its associated mortality and costs are high.28 In this retrospective cohort study, with a median time on NUC therapy of 39 months (∼3.3 years), 9 out of 120 (7.5%) patients developed HCC, which is similar to the rate reported by Yang et al.29 Among patients without cirrhosis, four developed HCC (3.7%), which is similar to the rates reported by Wong et al.18 and, recently by Arend et al.30 The incidence and clinical presentation of HCC in CHB patients differs significantly by country and ethnic origin. In western countries, HBV related HCC is clearly associated with cirrhosis and excessive alcohol intake,31 whereas in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, HCC can develop in carriers with mild liver fibrosis due to the long standing infection usually acquired at birth.32,33 Our findings corroborate data from Italy and Greece31,34 as on multivariate analysis, the independent predictors for HCC development despite NUC therapy were older age (aHR: 1.085; 95%CI: 1.021–1.153; p=0.009) and cirrhosis at baseline (aHR: 4.787; 95%CI: 1.105–20.734; p=0.036).

In the non-cirrhotic CHB patients of our study sample, multivariate analysis found that older age (aHR: 1.145; 95%CI: 1.028–1.277; p=0.014) and a lack of biochemical response to antiviral therapy (aHR: 124.046; 95%CI: 1.457–10559.174; p=0.034) were associated with HCC occurrence, which is supported by a very recent meta-analysis35 where age and the proportion of patients with elevated ALT levels predicted the incidence of HCC. Among the cirrhotic population there were no risk factors identified. This is evidence that age might be an important risk factor only in non-cirrhotic patients, whereas, cirrhosis itself is such a strong risk factor that it is seldom influenced by other co-factors (namely age) in the development of HCC. However, we cannot firmly conclude that because, as demonstrated in Table 1, our cirrhotic patients were significantly older at baseline than the non-cirrhotic cohort and due to small cirrhotic sample size (n=13).

Using Kaplan–Meier method (Fig. 2) we observed that patients with cirrhosis at baseline had a significantly higher cumulative incidence of HCC (log-rank test <0.001). Despite not reaching statistical significance, similarly to Wong et al.,18 in our study, previous antiviral treatment conferred a modest protective effect (HR: 0.411; 95%CI 0.085–1.982; p=0.268) against HCC occurrence (Table 2).

The need for development of HCC risk scores is underlined by the knowledge that NUC therapy cannot completely eliminate the risk of HCC and that the identification of high risk patients might lead intensive HCC surveillance strategies and early detection of HCC and thus to a greater chance of curative treatment with improved survival.36 In our study, at a median time on therapy of 3.3 years, the baseline REACH-B AUC obtained for prediction of HCC development (0.738; 95%CI: 0.521–0.955) was lower than the original and validation study of Yang et al.17 (AUC for predicting 3-year HCC risk of 0.811; 95%CI: 0.790–831) but similar to that obtained by Wong et al.18 (AUC for predicting 5-year HCC risk of 0.71; 95%CI: 0.62–0.81). The cutoff value of 8 points, yielded a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 51.6%, positive predictive value of 6.1% and negative predictive value of 98%, which is similar to the results of the study by Wong et al.18 Also, in parallel with the aforementioned study, the performance of the baseline REACH-B risk score in our subgroup of previously treatment-naïve patients was slightly inferior (Table 3). Our data highlights and confirms the major drawbacks of this risk score, which is its high false-positive rate, making it unable to correctly identify low-risk patients, as only 49 out of 95 patients without HCC were classified in the low-risk group. This might be due to the fact that, as in the original study, in our patients, cirrhosis was ruled out by ultrasound only. Another possible limitation of this risk score was described by Kim et al.14 Using a population mainly composed of TDF treated patients from the roll-over studies of registration trials, the real incidence of HCC and the incidence predicted based on the REACH-B score was evaluated. The authors found that after 3.3 years there was a progressive divergence between the predicted (by REACH-B score) and the observed number of HCC cases. Most studies addressing HCC occurrence during NUC therapy do not exceed 4–5 years, so it remains to be established if, with longer time on NUC therapy, HCC incidence remains stable. Hence, our data demonstrate that REACH-B score has many limitations especially in Caucasian populations, with AUC of 0.738, using Harrell's c-index, it is considered as of modest diagnostic accuracy only. This considerably limits the utility of the score.

In clinical practice, patients at increased baseline HCC risk should continue to undergo regular HCC surveillance according to published guidelines,19 however, enhancing this recommendations with the addition of predictive risk scores (REACH-B) may identify additional patients at higher risk of developing HCC (REACH-B score at baseline ≥8 points) and who would thus benefit from HCC surveillance strategies. Accordingly, patients at higher risk for HCC, despite being on antiviral therapy, should undergo HCC surveillance. Notwithstanding, we must note that there is recent evidence demonstrating that a higher HCC detection might not lead to a reduced HCC-related mortality.35

Another possible application for the REACH-B score could be the indication for antiviral treatment initiation, as shown in a recent study,37 where the authors demonstrated that the discriminatory performance of the REACH-B score in classifying antiviral treatment eligibility based on the local guideline (APASL 2012) was good/excellent with the exception of older HBeAg-positive patients.

Our study has some limitations, especially data regarding the cirrhotic cohort. It is evident that the cumulative incidence of HCC in cirrhotics was considerably high, exceeding most of previous reports of the South-European area (Italy, Greece, Spain), this is probably due to a small size of the sample. Also, most of the HCC cases in the cirrhotic cohort cumulate in the first months of therapy, suggesting a selection bias. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was based on clinical, laboratorial, radiological and endoscopic features (liver biopsy was not available for the non-cirrhotic population). Hence, patients with histological or early cirrhosis might have been unrecognized. Even with a long follow-up, due to a relatively small and rather heterogeneous cohort sample and the low number of events, our estimation of the accuracy of REACH-B risk score was limited. Another important limitation of our study is related to the fact that REACH-B score was originally derived from an Asian population. Additionally, HBsAg levels quantification, which is a novel marker, known by its high reproducibility and low cost, is currently not available in our institution. In fact, a link between HBsAg levels and HCC was first established by the ERADICATE-B cohort study.38 As a consequence, the original REACH-B risk calculator (known to underestimate the risk in patients with very low viral load at baseline) as suffered two major recent upgrades (using Asian cohorts only) in order to maximize its accuracy in predicting HCC occurrence. The most robust and costly REACH-B IIa, that incorporates the original factors plus HBV DNA and HBsAg levels quantification39 and the cheapest REACH-B IIb, which incorporates the original factors plus HBsAg levels quantification.40 Both upgraded risk calculators need further cost-effectiveness evaluation and external validation.5 The diagnosis of cirrhosis based on regular imaging and clinical parameters can be imprecise. Hence, recent developments in non-invasive tests of liver fibrosis may further improve the risk prediction. In fact, in a study performed by Lee and coworkers, the addition of liver stiffness measurement (by transient elastography) to REACH-B improved the diagnostic accuracy to predict liver-related events when compared to REACH-B score alone.39 Very recently, another risk score was developed by Papatheodoridis and coworkers in a large multicenter study in 1619 Caucasian European patients under NUC therapy (entecavir and tenofovir), the PAGE-B.40 The variables included in this risk score are: age, gender and platelet counts. This risk score appears to be very simple and probably the most suitable HCC risk predictor in Caucasian patients receiving antiviral therapy.

5ConclusionIn conclusion, continued HCC surveillance is recommended for CHB patients on antiviral therapy. Age, excessive alcohol intake and cirrhosis remain as the most important risk factors associated with HCC onset in CHB patients on antiviral therapy. REACH-B score has many limitations, especially in Caucasian populations. With an AUC of 0.738 it is considered as of modest diagnostic accuracy and this considerably limits the utility of the score. This is the first study assessing the utility of the REACH-B HCC-risk score in Portugal. Prospective studies using larger samples, longer follow-up periods on antiviral treatment and the use of non-invasive measurement of liver stiffness will be particularly useful in order to clarify the best algorithm for HCC surveillance in CHB patients under nucleos(t)ide analogs therapy.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

AuthorshipMagalhães-Costa P., Lebre L. and Chagas C. designed the research; Magalhães-Costa P. performed the research; Magalhães-Costa P. analyzed the data and performed the statistical analysis; Magalhães-Costa P. wrote the paper; Lebre L., Peixe P., Santos S. and Chagas C. critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.