Sinistral, or left-sided, portal hypertension (SPH) is a rare entity, with multiple potential causes. Gastrointestinal variceal bleeding and hypersplenism are its’ major clinical manifestations. The main aim of the present study is to summarize the clinical features of patients with SPH.

Patients and methodsThis was a retrospective analysis of consecutive patients with present or previous diagnosis of SHP, observed in a Gastroenterology Department, in a period of 2 years. Patients with clinical, radiological or laboratory alterations suggestive of cirrhosis were excluded. Causes of SPH, clinical manifestations and outcomes were registered. Potential factors associated with gastrointestinal bleeding were analyzed.

ResultsIn the study period a total of 22 patients (male – 17; mean age – 59.6±10.6 years) with SHP were included. Clinical manifestations were: asymptomatic/unspecific abdominal pain (n=14); gastrointestinal bleeding (n=8). Eleven (50%) patients had increased aminotransferases, GGT and/or alkaline phosphatase although liver function was normal in all of them. Causes of SPH were chronic pancreatitis (n=7), acute pancreatitis (n=7), pancreatic cancer (n=4), pancreatic surgery (n=3) and arteriovenous malformation (n=1). All patients had gastric and/or esophageal varices and seven had splenomegaly. Five (22.7%) had thrombocytopenia, associated with hypersplenism. Five patients (22.7%) were submitted to endoscopic treatment and eight were submitted to splenic artery embolization and/or splenectomy. There were no cases of variceal rebleeding and two patients died. Patients without liver enzymes elevation had a higher probability of gastrointestinal bleeding (87.5% vs. 28.6%; p=0.024).

ConclusionsAcute and chronic pancreatitis are the major causes of SHP. Gastrointestinal bleeding is the most important clinical manifestation and patients without liver enzyme elevation seem more prone to bleed. Specific treatment is seldom performed or needed.

A hipertensão portal esquerda ou sinistra (HTPS) é uma entidade rara, que pode resultar de diferentes etiologias. A hemorragia gastrointestinal de origem varicosa e o hiperesplenismo são as principais manifestações clínicas. O principal objetivo do presente estudo consiste em estabelecer os achados clínicos mais relevantes num grupo de doentes com HTPS.

Doentes e métodosFoi efetuada uma análise retrospetiva de um grupo consecutivo de doentes com HTPS diagnosticados ou acompanhados no serviço de Gastrenterologia durante o período de 2 anos. Os doentes com estigmas clínicos, radiológicos ou laboratoriais sugestivos de cirrose hepática foram excluídos. Foram registadas as etiologias, manifestações clínicas, tratamentos e evolução. Também foram analisados potenciais fatores associados com hemorragia digestiva como forma de apresentação.

ResultadosNeste período foram incluídos 22 doentes (sexo masculino – 17; média etária – 59,6±10,6 anos). As manifestações clínicas foram: assintomático/dor abdominal inespecífica (n=14); hemorragia gastrointestinal (n=8). A função hepática era normal em todos os doentes mas 11 (50%) apresentavam uma elevação da enzimologia hepática (aminotransferases, GGT e/ou fosfatase alcalina). As principais etiologias da HTPS foram a pancreatite crónica (n=7), a pancreatite aguda (n=7), os carcinomas pancreáticos (n=4), as cirurgias pancreáticas prévias (n=3) e uma malformação arterio-venosa (n=1). Foram identificadas varizes gástricas e/ou esofágicas em todos os doentes e 7 apresentavam esplenomegália. A trombocitopenia, associada ao hiperesplenismo, estava presente em 5 doentes (22,7%). Cinco doentes foram submetidos a tratamento endoscópico e oito foram sujeitos a embolização da artéria esplénica e/ou esplenectomia. Não se verificaram casos de recidiva hemorrágica e ocorreram duas mortes. Os doentes sem alterações da enzimologia hepática foram os mais propensos a apresentar hemorragia gastrointestinal (87,5% vs. 28,6%; p=0,024).

ConclusõesA pancreatite aguda e a pancreatite crónica são as principais causas da HTPS. A hemorragia gastrointestinal é a manifestação clínica mais relevante e os doentes sem alterações da enzimologia hepática parecem apresentar um risco superior para desenvolver esta complicação. O tratamento específico raramente é necessário/realizado.

Sinistral portal hypertension (SPH) is also known as splenoportal, left-sided, segmental, regional, localized, compartmental or lineal portal hypertension.1,2 Its’ pathophysiology was first outlined by Greenwald and Wasch in 1939.3 It is a rare entity, accounting for less than 5% of all patients with portal hypertension, and results from splenic vein thrombosis or occlusion, with patent extrahepatic portal vein.2,4–8 In fact, the name sinistral portal hypertension is a misnomer since portal pressure is usually within the normal range in these cases.2,9,10 Patients’ liver function is generally unaffected but gastric and/or esophageal varices are common and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) might be a potential life-threatening clinical manifestation.2,5 However, many patients are asymptomatic or have unspecific abdominal pain. Pancreatic inflammatory or neoplastic diseases are the main causes of SPH.1,2,4–8,11–13

UGIB can be controlled by endoscopic treatment but definitive therapy with splenic artery embolization or splenectomy can be deemed necessary. Treatment of asymptomatic SPH patients remains controversial.5,14

The present study summarizes clinical presentation, aetiologies and outcomes in a cohort of consecutive patients diagnosed with SPH. Potential factors associated with increased UGIB risk were also determined.

2Patients and methods2.1Patients and study designIn this single-centre study the medical records of all consecutive patients observed in a Gastroenterology Department during 2013–2014, with present or previous diagnosis of SPH were retrospectively analyzed. Diagnosis of SPH was based on criteria previously followed by Wang et al.: presence of pancreatic pathology; clinical, endoscopic or laboratory evidence of portal hypertension, including total or partial occlusion of the splenic vein and/or splenomegaly; exclusion of other causes of portal hypertension, such as concomitant portal vein thrombosis or liver cirrhosis.5 Patients with one or more clinical, imagiological and laboratory modifications suggestive of cirrhosis were immediately excluded from further analysis. Clinical manifestations, associated conditions, laboratory data, diagnostic evaluation, survival and outcomes were retrieved from medical records. Follow-up was based on the last clinical evaluation in the patient's history (index month – July 2015) taking in account the first imagiological examination that reported alterations compatible with SPH.

2.2StatisticsFor statistical analysis a 2-sample t test or a Mann–Whitney test were used for comparison of continuous variables, whereas a chi-square test or a 2-sided Fisher's exact test were used to compare the frequencies. The results are reported for significant variables in univariate analysis using adjusted odds ratios (OR) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). The statistical software package SPSS 20.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used.

2.3Ethical considerationsThe study adhered to all principles of good clinical practice. Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to endoscopic or other interventions deemed necessary.

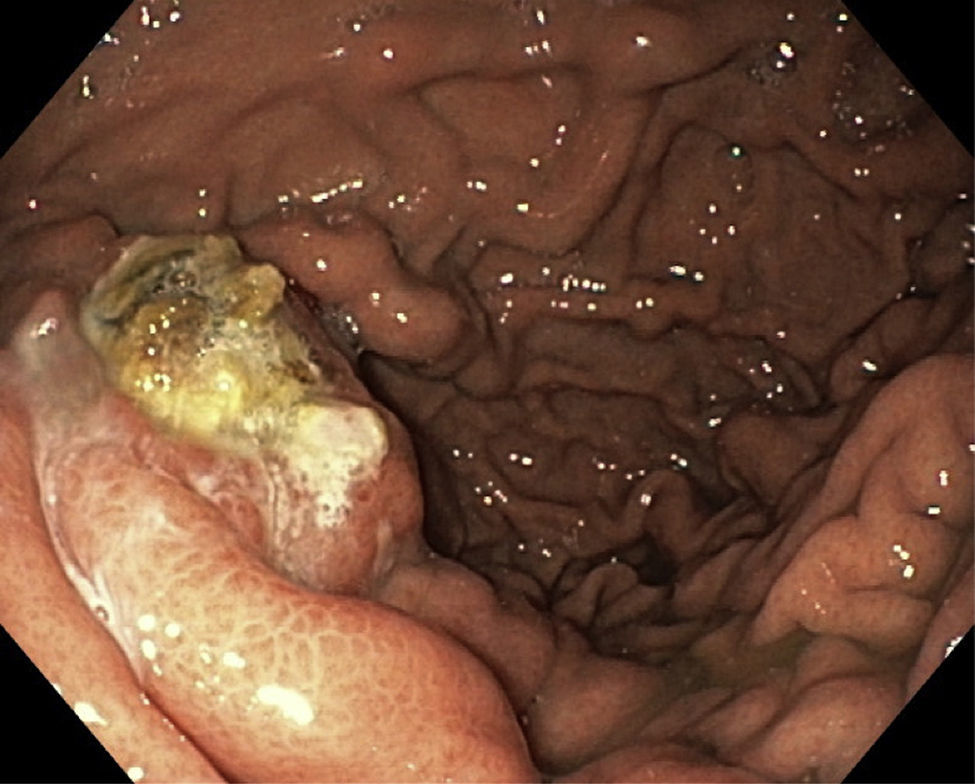

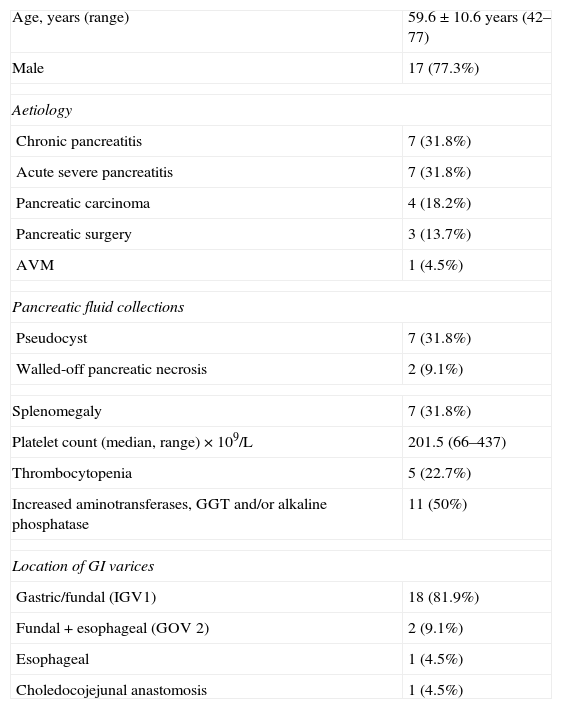

3ResultsIn this 2-year period a total of 22 patients (male – 17; mean age – 59.6±10.6 years, range 42–77 years) with SHP were included in the database. Eight patients (36.4%) had present or past history of UGIB due to esophageal and/or gastric varices (Fig. 1). There were no records of gastrointestinal bleeding from other locations or aetiologies. The remaining 14 patients were asymptomatic or had unspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain. Clinical and laboratory characteristics are resumed in Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics.

| Age, years (range) | 59.6±10.6 years (42–77) |

| Male | 17 (77.3%) |

| Aetiology | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 7 (31.8%) |

| Acute severe pancreatitis | 7 (31.8%) |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | 4 (18.2%) |

| Pancreatic surgery | 3 (13.7%) |

| AVM | 1 (4.5%) |

| Pancreatic fluid collections | |

| Pseudocyst | 7 (31.8%) |

| Walled-off pancreatic necrosis | 2 (9.1%) |

| Splenomegaly | 7 (31.8%) |

| Platelet count (median, range)×109/L | 201.5 (66–437) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (22.7%) |

| Increased aminotransferases, GGT and/or alkaline phosphatase | 11 (50%) |

| Location of GI varices | |

| Gastric/fundal (IGV1) | 18 (81.9%) |

| Fundal+esophageal (GOV 2) | 2 (9.1%) |

| Esophageal | 1 (4.5%) |

| Choledocojejunal anastomosis | 1 (4.5%) |

AVM, arteriovenous malformation; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; GI, gastrointestinal; GOV2, gastroesophageal varices type 2 (Sarin classification); IGV1, intragastric varices type 1 (Sarin classification).

All patients have no liver function abnormalities. Abdominal imaging was available for all patients (CT scan – 86.4%; Doppler ultrasound – 50%) (Fig. 2). In the imagiological evaluation there were no liver alterations suggestive of cirrhosis or abnormalities in the portal vein. Endoscopic ultrasound was also performed in nine patients (40.9%) with confirmation of gastrointestinal varices in all of them.

Eighteen patients had partial or total occlusion of spleen venous system due to acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic neoplasms. Three patients had history of pancreatic surgery, all due to malignant neoplasms: carcinoma of the Ampulla of Vater; pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour; pancreatic metastasis of kidney carcinoma. One patient had an arteriovenous malformation without occlusion of splenic vein.

Five patients with UGIB were submitted to endoscopic treatment (cyanoacrylate obliteration of fundal varices – 3; esophageal endoscopic variceal ligation – 2). The two patients with esophageal variceal bleeding were later included in an endoscopic elective ligation programme. Three patients with UGIB had no active bleeding in the first endoscopic evaluation and a watchful waiting strategy was adopted. These patients had no immediate rebleeding and were later referred for angiographic or surgical intervention.

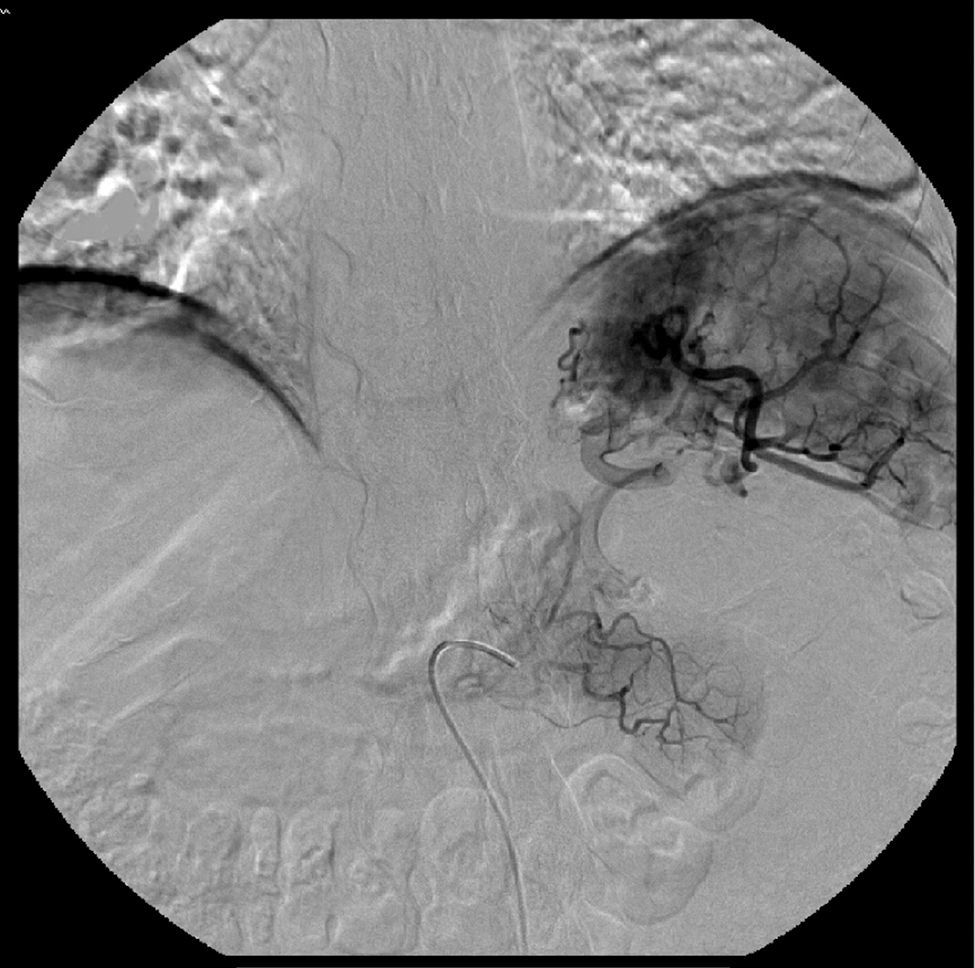

Splenic artery embolization was performed in five patients (Fig. 3). Two of them were afterwards submitted to splenectomy. Surgical treatment (splenectomy with or without pancreatic resection or pseudocyst drainage) was also performed in another three patients. Angiographic and/or surgical procedures were always preceded by administration of pneumococcal, meningococcal, Haemophilus influenza type B and influenza vaccines.

Study of hereditary thrombophilias was available in three cases and it was negative for all of them.

Five patients (22.7%) were medicated with anticoagulants (low molecular weight heparin and/or varfarin). The two patients with walled-off pancreatic necrosis were submitted to endoscopic drainage and necrosectomy.

Median follow-up time was 24 months (range 0–120 months). There were no cases of variceal rebleeding but two patients died, one due to pancreatic carcinoma and another from infectious complications not related with SHP.

Levels of aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase and/or gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase were normal in 87.5% of patients with UGIB, comparatively to 28.6% of patients without gastrointestinal haemorrhage (OR 17.50; 95% CI 1.59–191.89; p=0.024). There were no other factors predictive of increased risk for UGIB.

4DiscussionThrombotic occlusion of the splenic vein is generally the primary cause of SPH and pancreatic diseases are the main sources of such thrombosis.2,5 This occurs because the splenic vein traverses the pancreatic surface and the inflammatory or neoplastic pathologies can affect this vessel by a contiguity process.4,5,7,11–13 Other causes of SHP such as iatrogenic splenic vein injury after liver transplantation, partial gastrectomy, infiltration by other tumours, retroperitoneal fibrosis, abdominal/retroperitoneal tuberculosis, spontaneous splenic vein thrombosis, perirenal abscess, splenic lymphoma with splenic vein thrombosis, hereditary thrombophilias and idiopathic splenic vein thrombosis associated with pregnancy have also been linked with SPH but, these etiological factors are rare.2,8,15–23 In our series, pancreatitis (acute or chronic) and pancreatic neoplasms accounted for 81.8% of SHP cases. Three patients had history of pancreatic surgery but, according to the medical records, SHP was not present before surgery. SHP after pancreatic surgery was previously documented by other authors.7 Splenic vein ligation could be a cause of iatrogenic SHP but we were not able to confirm if that happened in these three patients.24 We assume that anatomical modifications after surgery were responsible for SHP development.

It is interesting to notice that one patient had not a total occlusion of the splenic vein. This patient presented with massive UGIB due to a fundal varix that was controlled with cyanoacrylate. The imagiological studies revealed an AVM involving the splenic artery and vein, determining a major overflow in the splenic vein and splenomegaly. To our knowledge this is the first case of SHP reported in medical literature with such aetiology. Physiopathologically the result was the same as total occlusion of splenic vein, with an increased pressure in the splenic venous system, which was transmitted through the anastomoses between the splenic vein and gastric or gastroepiploic veins, resulting in gastric or gastroesophageal varices. Regularly, esophageal varices are less common than fundal varices because the portal venous pressure is normal and blood drainage is through a patent coronary vein. Combined esophageal and gastric varices or isolated esophageal varices occur only when the coronary vein drains distal to the obstruction in the splenic vein.7,8 All our patients had gastric and/or esophageal varices and one, with previous surgery, also had choledocojejunal varices which were the source of bleeding. According to the literature 45–72% of patients with SHP present with UGIB due to ruptured varices and 25–38% had abdominal pain.2,8,12 The majority of our patients were asymptomatic or had unspecific abdominal pain and less than 40% presented UGIB. In another retrospective series only 15% of patients with splenic vein thrombosis experienced variceal bleeding.25 A prospective study in patients with chronic pancreatitis revealed that only 8% suffered from splenic vein thrombosis, the majority of whom did not experience any form of symptomatic GI bleeding.26 In a study from Koklu et al., involving 24 patients, chronic abdominal pain was also the most common complaint and only eight patients had present or past history of UGIB.8

SPH is often associated with splenomegaly and normal liver function.5 In our series only seven patients had a marked splenomegaly but liver function was normal in all cases. Some authors reported that splenomegaly was universal in their patients with SHP but, that did not happen in reports from another authors.5,7,8 Curiously, 50% of our patients had minor elevations of aminotransferases, GGT and/or alkaline phosphatase of different origins, including drug-related and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. These patients had, apparently, a lower risk of UGIB but we found no plausible explanation for such fact. It would be interesting to see if such finding is reproduced in series of SHP from another centres.

Management of SPH involves surgical correction of the underlying causes, such as pancreatic neoplasms or cysts, combined with splenectomy, to diminish the arterial inflow into the left portal system.6,9,14 More recently, splenic artery embolization was also advocated and it can be useful even before laparoscopic splenectomy in patients with splenomegaly.9,27–29 It can be a life-saving procedure in patients with massive UGIB after failure of endoscopic procedures.22 Endovascular procedures might be associated with serious complications such as partial gastric and/or pancreatic infarctions, splenic rupture, acute pancreatitis, pleural effusion, lung atelectasis, sepsis and the so-called “post-infarction syndrome”, represented by abdominal pain, leukocytosis and fever as well as splenic abscesses.28,29 Fortunately, we registered no complications in our patients. All of them were previously vaccinated and received antibiotic coverage during the procedure, as stated in medical literature.29,30

Surgical intervention was also advocated in the past for asymptomatic patients but, now it is not consensual and a conservative management might be acceptable in such circumstances.2,5,9,14

We identified five patients with hypersplenism. Three of them were submitted to splenic artery embolization and/or splenectomy. The other two had esophageal varices, amenable to endoscopic ligation, and the platelet count was only slightly diminished. Previous reports had also identified a high success rate in variceal eradication with the simple use of endoscopic therapies.31

From the eight patients with UGIB four were proposed for specific angiographic or surgical intervention, two were the ones with esophageal varices and another two had history of recent pancreatic surgery and a conservative approach was decided after endoscopic control of bleeding. Curiously, there were no cases of rebleeding or new bleedings during follow-up. Koklu et al. also found no cases of recurrent bleeding in six patients whom presented with gastrointestinal bleeding on admission and only one of them was submitted to splenectomy.8 Given these results we advocate a cautious approach to patients with SHP, even if symptomatic, since the benefit of angiographic or surgical interventions can be outweighed by its’ risks.

Anticoagulation for patients with accidentally detected thrombosis of veins from the splanchnic system is not consensual and gastrointestinal bleeding risk must be taken into account.32 There is limited information about anticoagulation in patients with SHP and this explains why only a few of our patients were under oral or parenteral anticoagulation. Theoretically anticoagulation should be instituted in all patients with inflammatory or neoplastic vein thrombosis but, in patients with fundal varices it is difficult to establish bleeding risk. Probably, anticoagulation in such cases should only be started after cyanoacrylate embolization. However, this procedure is not risk-free and it is difficult to assume such approach in asymptomatic patients. Further studies are needed in this area of knowledge. It is also interesting to notice that there are few cases of SHP related with coagulation disorders.

Our study has some important limitations that must be highlighted: it is a retrospective analysis that included patients with recent and previous diagnosis of SHP and so, there could be some bias of inclusion but, given the few number of patients diagnosed with SHP each year it will be difficult to perform a prospective study; there is no real data about the annual incidence of SHP in our series; it is not representative of an all region since only patients followed in the Gastroenterology Department were included; it would be interesting to have data about hereditary thrombophilias in all patients.

5ConclusionsSHP is generally associated with pancreatic disorders and in our series acute or chronic pancreatitis were the main aetiologies. Most patients are asymptomatic and UGIB is the main clinical manifestation. Surgical and/or endovascular treatment is advocated for patients with UGIB and/or hypersplenism but a conservative approach should be adopted in the remainder. Anticoagulation is not consensual and must be considered in a case-by-case scenario.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.