Low-value practices are avoidable interventions that provide no health benefits. The objective of this study was to conduct a narrative review of the recommendations for practices of low value-care in vascular prevention.

MethodsA narrative review of all low value-care recommendations for vascular prevention published in the main European and North American scientific societies for clinical practice guidelines between 2014 and 2024 was carried out.

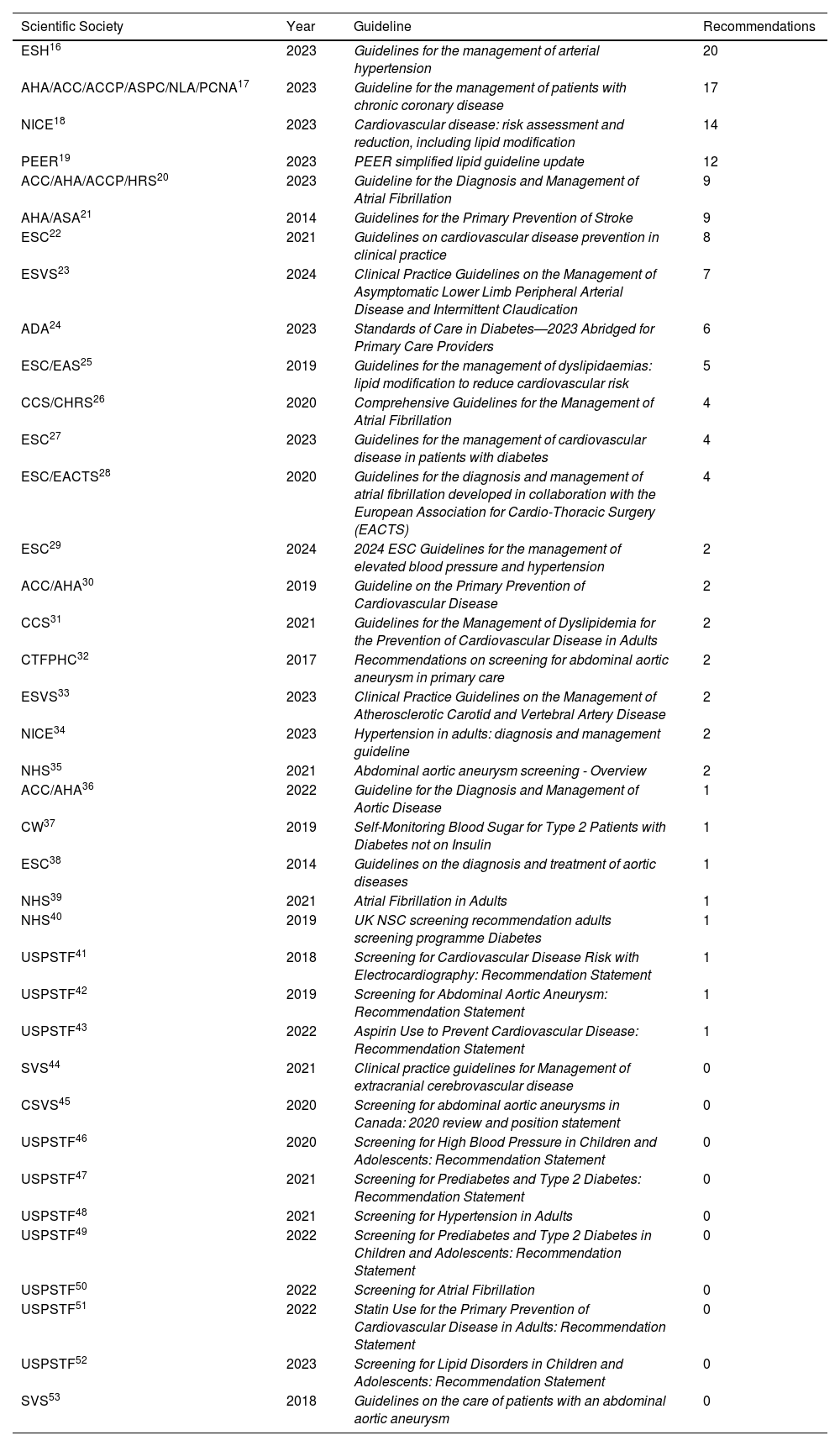

ResultsA total of 38 clinical practice guidelines and consensus documents from international organizations in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Europe were reviewed, 28 of which included between 1 and 20 recommendations on practices of low value-care in vascular prevention. The total number of recommendations was 141. The American Heart Association is the society that offers the largest number of recommendations of low value-care, with 39 recommendations (27.7%) in 5 clinical practice guidelines (13.2% of the total guidelines with recommendations). The guideline for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension is the guideline that concentrates the largest number of recommendations of low value-care in a single guideline, with 20 recommendations (14.2% of the total guidelines with recommendations).

ConclusionsThere are more and more guidelines that explicitly describe diagnostic or pharmacological activities of low value-care or Do Not Do Class III or recommendation D. Some guidelines agree, but others show clear discrepancies, which can illustrate the uncertainty of the scientific evidence and the differences in its interpretation.

Las prácticas de escaso valor son intervenciones evitables que no aportan beneficios para la salud. El objetivo de este estudio fue realizar una revisión de las recomendaciones de prácticas de escaso valor en prevención vascular.

MétodosSe hizo una búsqueda en las principales sociedades científicas europeas y norteamericanas de guías de práctica clínica de prevención vascular y se realizó una revisión narrativa de las recomendaciones de escaso valor publicadas desde el 2014 al 2024.

ResultadosFueron revisadas un total de 38 guías de práctica clínica y documentos de consenso de organismos internacionales de Estados Unidos, Canadá, Reino Unido, y Europa, 28 de los cuales incluían entre 1 y 20 recomendaciones sobre prácticas de escaso valor en prevención vascular. El número total de recomendaciones fue de 141. La American Heart Association es la sociedad que mayor número de recomendaciones de escaso valor ofrece, 39 recomendaciones (27,7%) en 5 guías de práctica clínica (13,2% de las guías con alguna recomendación). La guía para el manejo de la hipertensión arterial de la European Society of Hypertension es la guía que mayor número de recomendaciones de escaso valor concentra en una única guía, con 20 recomendaciones (14,2%).

ConclusionesCada vez hay más guías que explícitamente describen actividades diagnósticas o farmacológicas de escaso valor o de No Hacer de clase III o recomendación D. Algunas guías coinciden, pero otras muestran discrepancias, lo que puede ilustrar la incertidumbre de la evidencia científica y las diferencias en su interpretación.

Vascular diseases (VD) are the leading cause of death in Spain, with 121,341 deaths in 2022, accounting for 26.1% of all fatalities. Although mortality has decreased from 34.9% in 2000 to 24.3% in 2022, VD continues to have a significant public health impact. Mortality from VD has been declining since the mid-1970s, mainly due to reduced mortality from cerebrovascular and coronary diseases.1 However, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted this trend, causing an increase in VD mortality in recent years.2 Additionally, the rate of hospital morbidity due to circulatory system diseases has been high, with significant differences between cities and regions in Spain.3,4 The prevalence of VD in Spain in 2019 was 9.8%; 52.6% of those affected were women, and 47.4% were men.5 These figures highlight the importance of addressing vascular risk factors, considering health inequities, particularly gender disparities, to continue reducing the burden of these diseases and avoiding low-value clinical practices. Low-value practices, also called unnecessary practices or practices to avoid, are preventable interventions that do not provide health benefits due to lack of efficacy, associated risks, or the availability of equally effective but less costly alternatives. Part of the increased prevalence of some diseases is due to overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and healthcare focused on low-value practices. Overutilization includes excessive surveillance of asymptomatic individuals, low-value investigations in symptomatic individuals, misuse of biomarkers, and inappropriate follow-up. Tackling overutilization by identifying non-beneficial practices and establishing recommendations to avoid them will prevent unnecessary harm and enable more efficient use of resources, improving healthcare quality, efficiency, safety, and system sustainability.6 There are several nationally and internationally initiatives along these lines. For example, in Spain, the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine (semFYC) has published a series of Do Not Do documents on various topics, such as hypertension, mental health, or adolescence.7 The Spanish Association of Pediatrics (AEP) has also developed Do Not Do recommendations in different pediatric care settings, aiming to identify practices to avoid in pediatric care, including primary care, emergency, hospitalization, intensive care, and home care.8,9 Additionally, the Clinical Practice Improvement Initiative (MAPAC), involving various hospitals in Spain, and the ESSENCIAL10 project, led by the Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia (AquAS) with support from the Catalan Department of Health, are notable efforts. ESSENCIAL regularly updates recommendations across different medical specialties. The Aragon Institute of Health Sciences11 supports evidence-based decision-making through clinical practice guidelines and includes a specific section on Do Not Do recommendations. These recommendations have been supported by the Spanish Ministry of Health in its commitment to quality, inviting scientific societies to submit proposals for inclusion in the national catalog. Internationally, initiatives like Choosing Wisely,12 founded in the United States in 2012 and rapidly expanded to countries like Canada, Australia, Colombia, and Argentina, recommend Do and Do Not Do practices. Currently, Choosing Wisely in the U.S. is overseen by American scientific societies responsible for issuing recommendations. Other initiatives include Smarter Medicine13 in Switzerland and Slow Medicine14 in Italy. In this context, it is crucial to thoroughly review vascular prevention practices to identify those that should be avoided. Recently, an article summarizing, non-exhaustively and consensually, drugs used in different cardiovascular pathologies that should be discontinued or reevaluated due to lack of benefit or the existence of better alternatives was published.15

This document aims to review international initiatives and clinical practice guidelines in vascular pathology, evaluate recommendations on low-value practices in vascular prevention, and examine the scientific evidence supporting them.

MethodsA narrative review of clinical practice guidelines for vascular prevention published in English from 2014 to 2024 was conducted. Searches were carried out among major European and North American scientific societies and in PubMed using MeSH terms and natural language. Only guidelines containing low-value practice recommendations, selected by two independent reviewers, were included. Low-value recommendations were extracted and categorized based on pathology, lifestyle, treatment or diagnosis, population (age, gender, and other conditions), and primary data source. In cases of discrepancies among recommendations from guidelines within the same scientific society, the most recent recommendations were selected. Additionally, studies underpinning these recommendations were reviewed, and a summary of findings was compiled into tables grouped by lifestyle, diagnostic, or therapeutic processes. For example, the European Society of Cardiology uses the class III, stating that there is the evidence or general agreement that the given treatment or procedure is not useful/effective, and in some cases may be harmful. The US Preventive Task Force classifies as grade D when the recommendation is against the service, stating that there is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits.

ResultsA total of 38 clinical practice guidelines and consensus documents from international organizations in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Europe were reviewed (Table 1). Of these, 28 included between 1 and 20 recommendations on low-value practices in vascular prevention, resulting in 141 recommendations analyzed. The American Heart Association, in collaboration with other scientific societies, has made the highest number of recommendations on low-value or unnecessary practices, with a total of 39 recommendations (27.7% of the total recommendations) in 5 clinical practice guidelines (13.2% of the total guidelines).

Guidelines reviewed, and number of recommendations extracted per guideline.

| Scientific Society | Year | Guideline | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESH16 | 2023 | Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension | 20 |

| AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA17 | 2023 | Guideline for the management of patients with chronic coronary disease | 17 |

| NICE18 | 2023 | Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification | 14 |

| PEER19 | 2023 | PEER simplified lipid guideline update | 12 |

| ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS20 | 2023 | Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation | 9 |

| AHA/ASA21 | 2014 | Guidelines for the Primary Prevention of Stroke | 9 |

| ESC22 | 2021 | Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice | 8 |

| ESVS23 | 2024 | Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Asymptomatic Lower Limb Peripheral Arterial Disease and Intermittent Claudication | 7 |

| ADA24 | 2023 | Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023 Abridged for Primary Care Providers | 6 |

| ESC/EAS25 | 2019 | Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk | 5 |

| CCS/CHRS26 | 2020 | Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation | 4 |

| ESC27 | 2023 | Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes | 4 |

| ESC/EACTS28 | 2020 | Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) | 4 |

| ESC29 | 2024 | 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension | 2 |

| ACC/AHA30 | 2019 | Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease | 2 |

| CCS31 | 2021 | Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults | 2 |

| CTFPHC32 | 2017 | Recommendations on screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in primary care | 2 |

| ESVS33 | 2023 | Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Atherosclerotic Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease | 2 |

| NICE34 | 2023 | Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management guideline | 2 |

| NHS35 | 2021 | Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening - Overview | 2 |

| ACC/AHA36 | 2022 | Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease | 1 |

| CW37 | 2019 | Self-Monitoring Blood Sugar for Type 2 Patients with Diabetes not on Insulin | 1 |

| ESC38 | 2014 | Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases | 1 |

| NHS39 | 2021 | Atrial Fibrillation in Adults | 1 |

| NHS40 | 2019 | UK NSC screening recommendation adults screening programme Diabetes | 1 |

| USPSTF41 | 2018 | Screening for Cardiovascular Disease Risk with Electrocardiography: Recommendation Statement | 1 |

| USPSTF42 | 2019 | Screening for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Recommendation Statement | 1 |

| USPSTF43 | 2022 | Aspirin Use to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease: Recommendation Statement | 1 |

| SVS44 | 2021 | Clinical practice guidelines for Management of extracranial cerebrovascular disease | 0 |

| CSVS45 | 2020 | Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms in Canada: 2020 review and position statement | 0 |

| USPSTF46 | 2020 | Screening for High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: Recommendation Statement | 0 |

| USPSTF47 | 2021 | Screening for Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes: Recommendation Statement | 0 |

| USPSTF48 | 2021 | Screening for Hypertension in Adults | 0 |

| USPSTF49 | 2022 | Screening for Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents: Recommendation Statement | 0 |

| USPSTF50 | 2022 | Screening for Atrial Fibrillation | 0 |

| USPSTF51 | 2022 | Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Recommendation Statement | 0 |

| USPSTF52 | 2023 | Screening for Lipid Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Recommendation Statement | 0 |

| SVS53 | 2018 | Guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm | 0 |

American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), Patients Experience Evidence Research Group (PEER), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), European Society of Cardiology (ESC), American Diabetes Association (ADA), European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS), Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS), Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC), European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS), National Health Service (NHS), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Choosing Wisely (CW), Society of Vascular Surgery (SVS), United States Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF), Canadian Society of Vascular Surgery (CSVS), American Stroke Association (ASA), European Society of Hypertension (ESH), American Society for Preventive Cardiology (ASPC), National Lipid Association (NLA), Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association (PCNA).

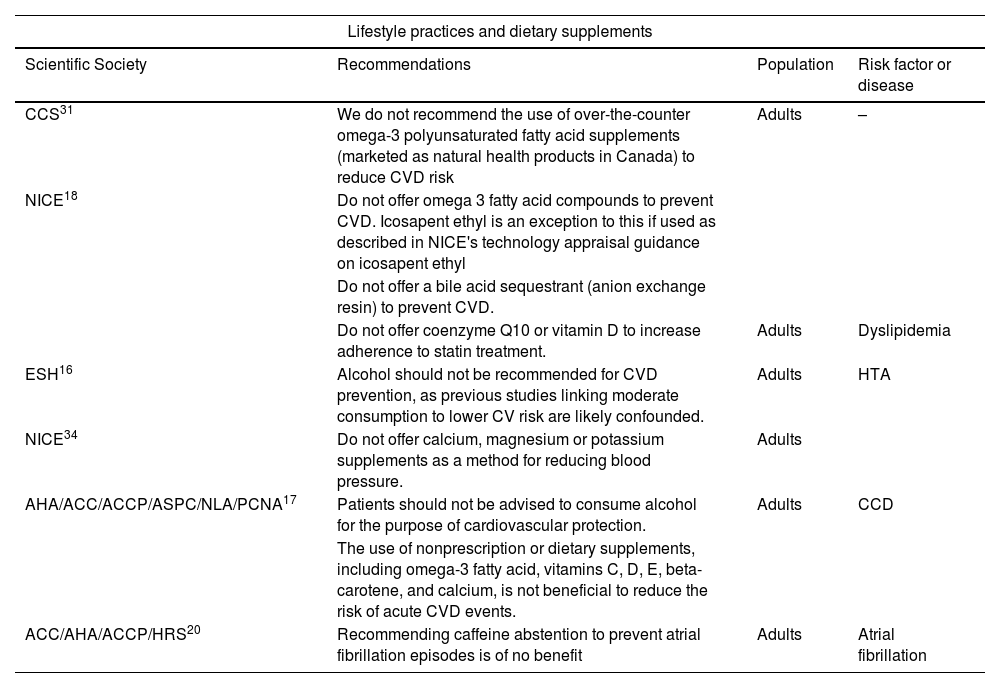

The European Society of Hypertension's guideline16 for the management of hypertension contains the highest number of low-value or unnecessary recommendations in a single guideline, with 20 recommendations (14.2% of the total recommendations). Only 9 (6.4%) of the 141 recommendations referred to lifestyle practices, mainly for hypertension. Table 2 includes low-value practices related to lifestyle.

Low-value or unnecessary practices recommendations against lifestyle practices and dietary supplements.

| Lifestyle practices and dietary supplements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Society | Recommendations | Population | Risk factor or disease |

| CCS31 | We do not recommend the use of over-the-counter omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplements (marketed as natural health products in Canada) to reduce CVD risk | Adults | – |

| NICE18 | Do not offer omega 3 fatty acid compounds to prevent CVD. Icosapent ethyl is an exception to this if used as described in NICE's technology appraisal guidance on icosapent ethyl | ||

| Do not offer a bile acid sequestrant (anion exchange resin) to prevent CVD. | |||

| Do not offer coenzyme Q10 or vitamin D to increase adherence to statin treatment. | Adults | Dyslipidemia | |

| ESH16 | Alcohol should not be recommended for CVD prevention, as previous studies linking moderate consumption to lower CV risk are likely confounded. | Adults | HTA |

| NICE34 | Do not offer calcium, magnesium or potassium supplements as a method for reducing blood pressure. | Adults | |

| AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA17 | Patients should not be advised to consume alcohol for the purpose of cardiovascular protection. | Adults | CCD |

| The use of nonprescription or dietary supplements, including omega-3 fatty acid, vitamins C, D, E, beta-carotene, and calcium, is not beneficial to reduce the risk of acute CVD events. | |||

| ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS20 | Recommending caffeine abstention to prevent atrial fibrillation episodes is of no benefit | Adults | Atrial fibrillation |

ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CCD: chronic coronary disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease.

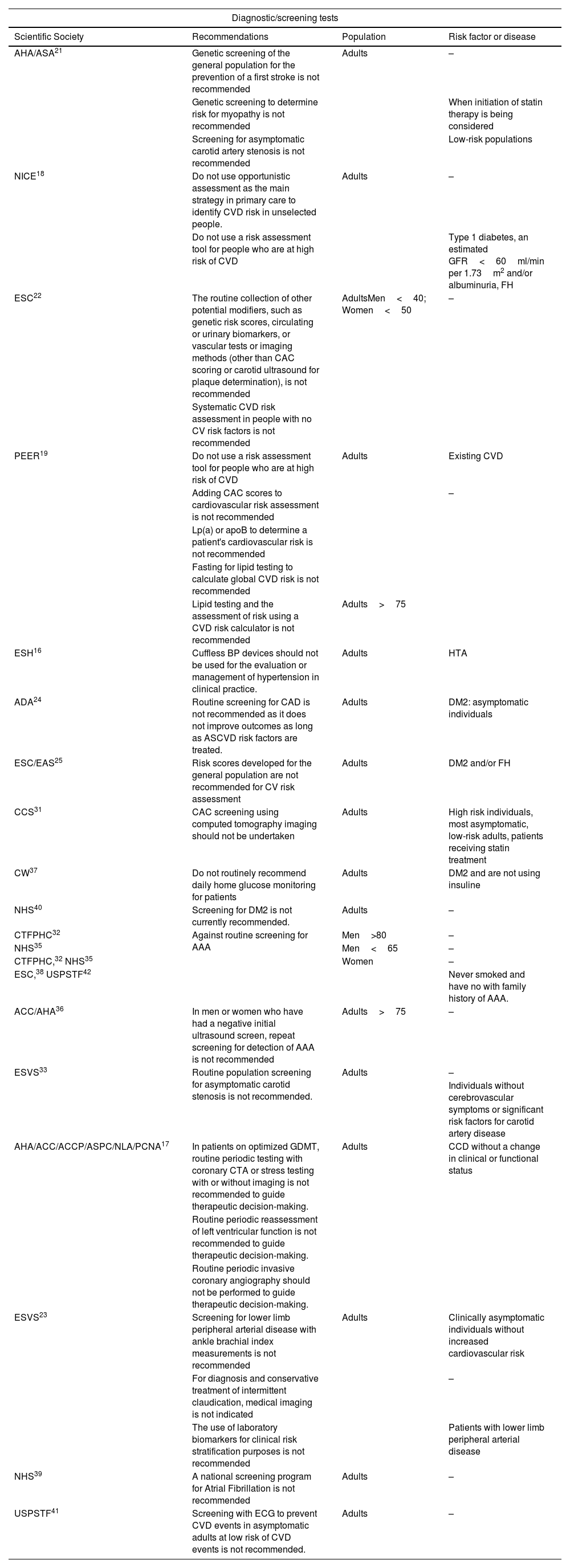

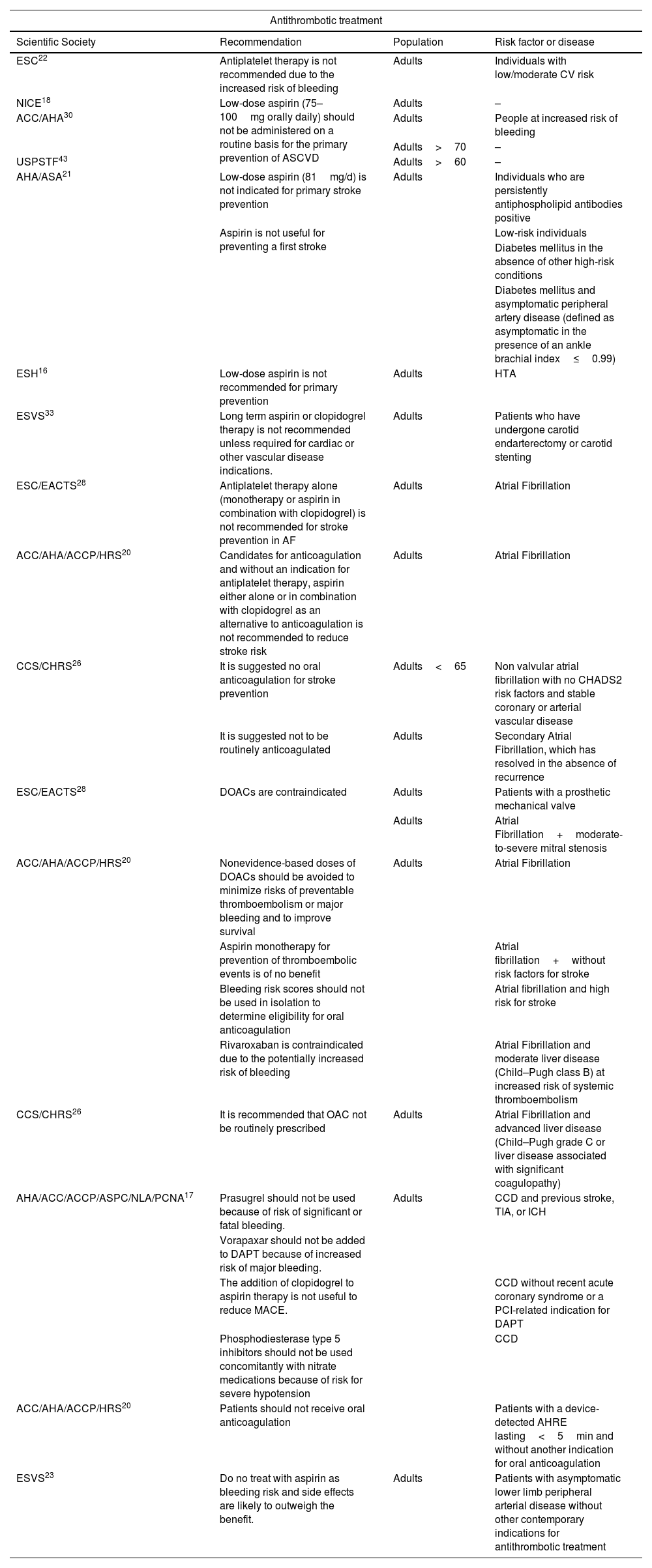

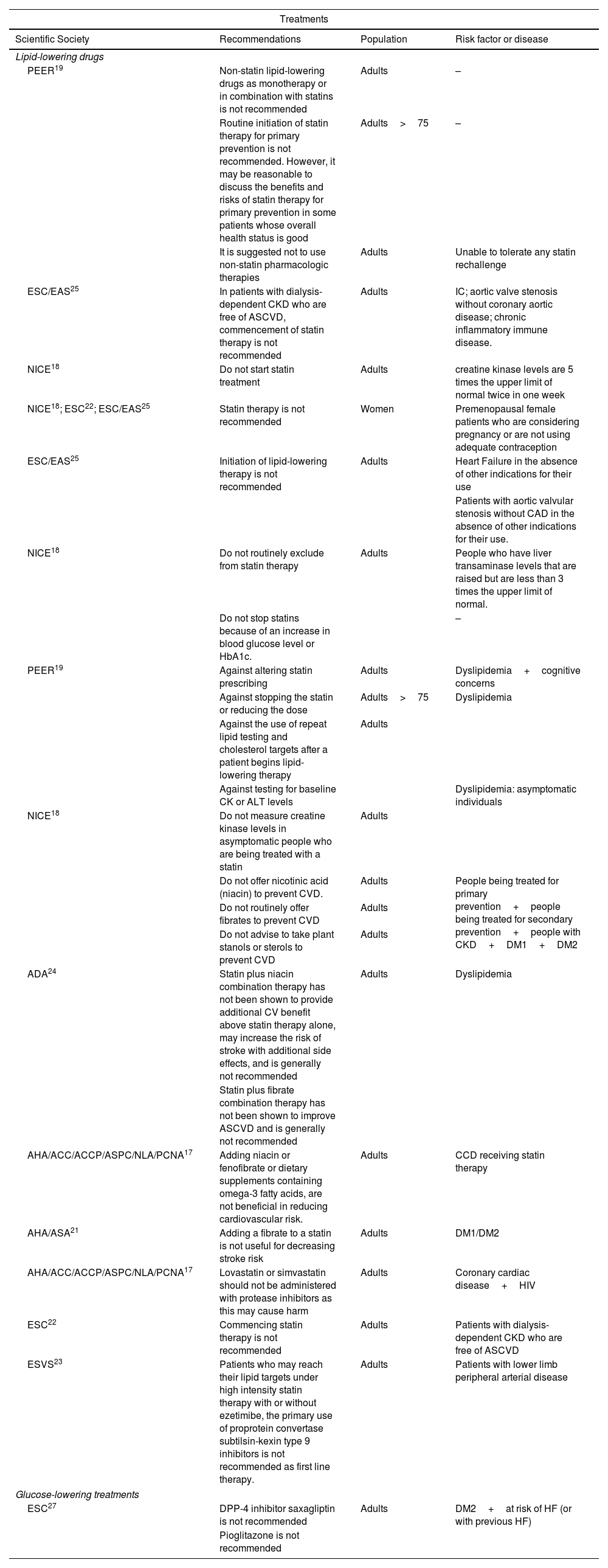

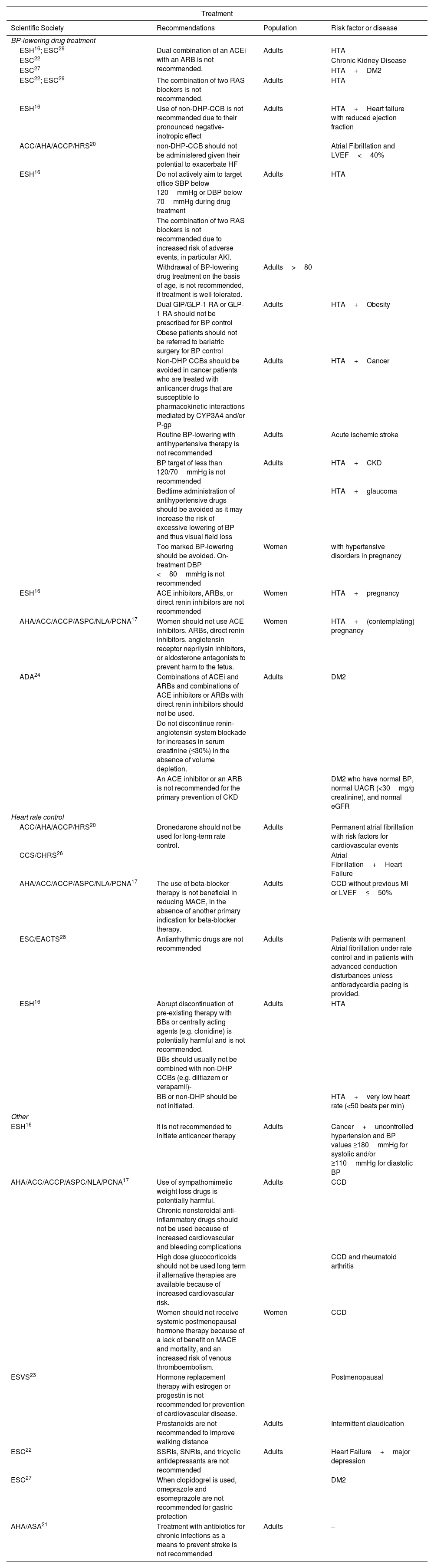

Table 3 lists the low-value practices related to diagnostic tests. Tables 4–6 cover low-value practices related to different treatments: antiplatelet, hypoglycemic, and lipid-lowering, antihypertensive, and others.

Low-value or unnecessary practices recommendations against diagnostic/screening tests.

| Diagnostic/screening tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Society | Recommendations | Population | Risk factor or disease |

| AHA/ASA21 | Genetic screening of the general population for the prevention of a first stroke is not recommended | Adults | – |

| Genetic screening to determine risk for myopathy is not recommended | When initiation of statin therapy is being considered | ||

| Screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis is not recommended | Low-risk populations | ||

| NICE18 | Do not use opportunistic assessment as the main strategy in primary care to identify CVD risk in unselected people. | Adults | – |

| Do not use a risk assessment tool for people who are at high risk of CVD | Type 1 diabetes, an estimated GFR<60ml/min per 1.73m2 and/or albuminuria, FH | ||

| ESC22 | The routine collection of other potential modifiers, such as genetic risk scores, circulating or urinary biomarkers, or vascular tests or imaging methods (other than CAC scoring or carotid ultrasound for plaque determination), is not recommended | AdultsMen<40; Women<50 | – |

| Systematic CVD risk assessment in people with no CV risk factors is not recommended | |||

| PEER19 | Do not use a risk assessment tool for people who are at high risk of CVD | Adults | Existing CVD |

| Adding CAC scores to cardiovascular risk assessment is not recommended | – | ||

| Lp(a) or apoB to determine a patient's cardiovascular risk is not recommended | |||

| Fasting for lipid testing to calculate global CVD risk is not recommended | |||

| Lipid testing and the assessment of risk using a CVD risk calculator is not recommended | Adults>75 | ||

| ESH16 | Cuffless BP devices should not be used for the evaluation or management of hypertension in clinical practice. | Adults | HTA |

| ADA24 | Routine screening for CAD is not recommended as it does not improve outcomes as long as ASCVD risk factors are treated. | Adults | DM2: asymptomatic individuals |

| ESC/EAS25 | Risk scores developed for the general population are not recommended for CV risk assessment | Adults | DM2 and/or FH |

| CCS31 | CAC screening using computed tomography imaging should not be undertaken | Adults | High risk individuals, most asymptomatic, low-risk adults, patients receiving statin treatment |

| CW37 | Do not routinely recommend daily home glucose monitoring for patients | Adults | DM2 and are not using insuline |

| NHS40 | Screening for DM2 is not currently recommended. | Adults | – |

| CTFPHC32 | Against routine screening for AAA | Men>80 | – |

| NHS35 | Men<65 | – | |

| CTFPHC,32 NHS35 | Women | – | |

| ESC,38 USPSTF42 | Never smoked and have no with family history of AAA. | ||

| ACC/AHA36 | In men or women who have had a negative initial ultrasound screen, repeat screening for detection of AAA is not recommended | Adults>75 | – |

| ESVS33 | Routine population screening for asymptomatic carotid stenosis is not recommended. | Adults | – |

| Individuals without cerebrovascular symptoms or significant risk factors for carotid artery disease | |||

| AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA17 | In patients on optimized GDMT, routine periodic testing with coronary CTA or stress testing with or without imaging is not recommended to guide therapeutic decision-making. | Adults | CCD without a change in clinical or functional status |

| Routine periodic reassessment of left ventricular function is not recommended to guide therapeutic decision-making. | |||

| Routine periodic invasive coronary angiography should not be performed to guide therapeutic decision-making. | |||

| ESVS23 | Screening for lower limb peripheral arterial disease with ankle brachial index measurements is not recommended | Adults | Clinically asymptomatic individuals without increased cardiovascular risk |

| For diagnosis and conservative treatment of intermittent claudication, medical imaging is not indicated | – | ||

| The use of laboratory biomarkers for clinical risk stratification purposes is not recommended | Patients with lower limb peripheral arterial disease | ||

| NHS39 | A national screening program for Atrial Fibrillation is not recommended | Adults | – |

| USPSTF41 | Screening with ECG to prevent CVD events in asymptomatic adults at low risk of CVD events is not recommended. | Adults | – |

AAA: Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CAD: coronary artery disease; CAC: coronary artery calcium; CVD: cardiovascular disease; ECG: resting or exercise electrocardiography; GDMT: goal-directed medical therapy; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; FH: familial hypercholesterolaemia.

Low-value or unnecessary practices recommendations against antithrombotic treatment.

| Antithrombotic treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Society | Recommendation | Population | Risk factor or disease |

| ESC22 | Antiplatelet therapy is not recommended due to the increased risk of bleeding | Adults | Individuals with low/moderate CV risk |

| NICE18 | Low-dose aspirin (75–100mg orally daily) should not be administered on a routine basis for the primary prevention of ASCVD | Adults | – |

| ACC/AHA30 | Adults | People at increased risk of bleeding | |

| Adults>70 | – | ||

| USPSTF43 | Adults>60 | – | |

| AHA/ASA21 | Low-dose aspirin (81mg/d) is not indicated for primary stroke prevention | Adults | Individuals who are persistently antiphospholipid antibodies positive |

| Aspirin is not useful for preventing a first stroke | Low-risk individuals | ||

| Diabetes mellitus in the absence of other high-risk conditions | |||

| Diabetes mellitus and asymptomatic peripheral artery disease (defined as asymptomatic in the presence of an ankle brachial index≤0.99) | |||

| ESH16 | Low-dose aspirin is not recommended for primary prevention | Adults | HTA |

| ESVS33 | Long term aspirin or clopidogrel therapy is not recommended unless required for cardiac or other vascular disease indications. | Adults | Patients who have undergone carotid endarterectomy or carotid stenting |

| ESC/EACTS28 | Antiplatelet therapy alone (monotherapy or aspirin in combination with clopidogrel) is not recommended for stroke prevention in AF | Adults | Atrial Fibrillation |

| ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS20 | Candidates for anticoagulation and without an indication for antiplatelet therapy, aspirin either alone or in combination with clopidogrel as an alternative to anticoagulation is not recommended to reduce stroke risk | Adults | Atrial Fibrillation |

| CCS/CHRS26 | It is suggested no oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention | Adults<65 | Non valvular atrial fibrillation with no CHADS2 risk factors and stable coronary or arterial vascular disease |

| It is suggested not to be routinely anticoagulated | Adults | Secondary Atrial Fibrillation, which has resolved in the absence of recurrence | |

| ESC/EACTS28 | DOACs are contraindicated | Adults | Patients with a prosthetic mechanical valve |

| Adults | Atrial Fibrillation+moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis | ||

| ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS20 | Nonevidence-based doses of DOACs should be avoided to minimize risks of preventable thromboembolism or major bleeding and to improve survival | Adults | Atrial Fibrillation |

| Aspirin monotherapy for prevention of thromboembolic events is of no benefit | Atrial fibrillation+without risk factors for stroke | ||

| Bleeding risk scores should not be used in isolation to determine eligibility for oral anticoagulation | Atrial fibrillation and high risk for stroke | ||

| Rivaroxaban is contraindicated due to the potentially increased risk of bleeding | Atrial Fibrillation and moderate liver disease (Child–Pugh class B) at increased risk of systemic thromboembolism | ||

| CCS/CHRS26 | It is recommended that OAC not be routinely prescribed | Adults | Atrial Fibrillation and advanced liver disease (Child–Pugh grade C or liver disease associated with significant coagulopathy) |

| AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA17 | Prasugrel should not be used because of risk of significant or fatal bleeding. | Adults | CCD and previous stroke, TIA, or ICH |

| Vorapaxar should not be added to DAPT because of increased risk of major bleeding. | |||

| The addition of clopidogrel to aspirin therapy is not useful to reduce MACE. | CCD without recent acute coronary syndrome or a PCI-related indication for DAPT | ||

| Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors should not be used concomitantly with nitrate medications because of risk for severe hypotension | CCD | ||

| ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS20 | Patients should not receive oral anticoagulation | Patients with a device-detected AHRE lasting<5min and without another indication for oral anticoagulation | |

| ESVS23 | Do no treat with aspirin as bleeding risk and side effects are likely to outweigh the benefit. | Adults | Patients with asymptomatic lower limb peripheral arterial disease without other contemporary indications for antithrombotic treatment |

AHRE: atrial high-rate episode; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CCD: coronary cardiovascular disease; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; DOACs: direct oral anticoagulants; ICH: intracerebral hemorrhage; PCI: Periprocedural myocardial injury; TIA: transient ischemic attack; OAC: oral anticoagulation.

Low-value or unnecessary practices recommendations against lipid-lowering and glucose-lowering treatment.

| Treatments | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Society | Recommendations | Population | Risk factor or disease |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | |||

| PEER19 | Non-statin lipid-lowering drugs as monotherapy or in combination with statins is not recommended | Adults | – |

| Routine initiation of statin therapy for primary prevention is not recommended. However, it may be reasonable to discuss the benefits and risks of statin therapy for primary prevention in some patients whose overall health status is good | Adults>75 | – | |

| It is suggested not to use non-statin pharmacologic therapies | Adults | Unable to tolerate any statin rechallenge | |

| ESC/EAS25 | In patients with dialysis-dependent CKD who are free of ASCVD, commencement of statin therapy is not recommended | Adults | IC; aortic valve stenosis without coronary aortic disease; chronic inflammatory immune disease. |

| NICE18 | Do not start statin treatment | Adults | creatine kinase levels are 5 times the upper limit of normal twice in one week |

| NICE18; ESC22; ESC/EAS25 | Statin therapy is not recommended | Women | Premenopausal female patients who are considering pregnancy or are not using adequate contraception |

| ESC/EAS25 | Initiation of lipid-lowering therapy is not recommended | Adults | Heart Failure in the absence of other indications for their use |

| Patients with aortic valvular stenosis without CAD in the absence of other indications for their use. | |||

| NICE18 | Do not routinely exclude from statin therapy | Adults | People who have liver transaminase levels that are raised but are less than 3 times the upper limit of normal. |

| Do not stop statins because of an increase in blood glucose level or HbA1c. | – | ||

| PEER19 | Against altering statin prescribing | Adults | Dyslipidemia+cognitive concerns |

| Against stopping the statin or reducing the dose | Adults>75 | Dyslipidemia | |

| Against the use of repeat lipid testing and cholesterol targets after a patient begins lipid-lowering therapy | Adults | ||

| Against testing for baseline CK or ALT levels | Dyslipidemia: asymptomatic individuals | ||

| NICE18 | Do not measure creatine kinase levels in asymptomatic people who are being treated with a statin | Adults | |

| Do not offer nicotinic acid (niacin) to prevent CVD. | Adults | People being treated for primary prevention+people being treated for secondary prevention+people with CKD+DM1+DM2 | |

| Do not routinely offer fibrates to prevent CVD | Adults | ||

| Do not advise to take plant stanols or sterols to prevent CVD | Adults | ||

| ADA24 | Statin plus niacin combination therapy has not been shown to provide additional CV benefit above statin therapy alone, may increase the risk of stroke with additional side effects, and is generally not recommended | Adults | Dyslipidemia |

| Statin plus fibrate combination therapy has not been shown to improve ASCVD and is generally not recommended | |||

| AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA17 | Adding niacin or fenofibrate or dietary supplements containing omega-3 fatty acids, are not beneficial in reducing cardiovascular risk. | Adults | CCD receiving statin therapy |

| AHA/ASA21 | Adding a fibrate to a statin is not useful for decreasing stroke risk | Adults | DM1/DM2 |

| AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA17 | Lovastatin or simvastatin should not be administered with protease inhibitors as this may cause harm | Adults | Coronary cardiac disease+HIV |

| ESC22 | Commencing statin therapy is not recommended | Adults | Patients with dialysis-dependent CKD who are free of ASCVD |

| ESVS23 | Patients who may reach their lipid targets under high intensity statin therapy with or without ezetimibe, the primary use of proprotein convertase subtilsin-kexin type 9 inhibitors is not recommended as first line therapy. | Adults | Patients with lower limb peripheral arterial disease |

| Glucose-lowering treatments | |||

| ESC27 | DPP-4 inhibitor saxagliptin is not recommended | Adults | DM2+at risk of HF (or with previous HF) |

| Pioglitazone is not recommended | |||

CAD: coronary artery disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; DPP-4: dipeptidyl peptidase 4; HF: heart failure.

Low-value or unnecessary practices recommendations against antihypertensive treatment.

| Treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Society | Recommendations | Population | Risk factor or disease |

| BP-lowering drug treatment | |||

| ESH16; ESC29 | Dual combination of an ACEi with an ARB is not recommended. | Adults | HTA |

| ESC22 | Chronic Kidney Disease | ||

| ESC27 | HTA+DM2 | ||

| ESC22; ESC29 | The combination of two RAS blockers is not recommended. | Adults | HTA |

| ESH16 | Use of non-DHP-CCB is not recommended due to their pronounced negative-inotropic effect | Adults | HTA+Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS20 | non-DHP-CCB should not be administered given their potential to exacerbate HF | Atrial Fibrillation and LVEF<40% | |

| ESH16 | Do not actively aim to target office SBP below 120mmHg or DBP below 70mmHg during drug treatment | Adults | HTA |

| The combination of two RAS blockers is not recommended due to increased risk of adverse events, in particular AKI. | |||

| Withdrawal of BP-lowering drug treatment on the basis of age, is not recommended, if treatment is well tolerated. | Adults>80 | ||

| Dual GIP/GLP-1 RA or GLP-1 RA should not be prescribed for BP control | Adults | HTA+Obesity | |

| Obese patients should not be referred to bariatric surgery for BP control | |||

| Non-DHP CCBs should be avoided in cancer patients who are treated with anticancer drugs that are susceptible to pharmacokinetic interactions mediated by CYP3A4 and/or P-gp | Adults | HTA+Cancer | |

| Routine BP-lowering with antihypertensive therapy is not recommended | Adults | Acute ischemic stroke | |

| BP target of less than 120/70mmHg is not recommended | Adults | HTA+CKD | |

| Bedtime administration of antihypertensive drugs should be avoided as it may increase the risk of excessive lowering of BP and thus visual field loss | HTA+glaucoma | ||

| Too marked BP-lowering should be avoided. On-treatment DBP <80mmHg is not recommended | Women | with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy | |

| ESH16 | ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or direct renin inhibitors are not recommended | Women | HTA+pregnancy |

| AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA17 | Women should not use ACE inhibitors, ARBs, direct renin inhibitors, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors, or aldosterone antagonists to prevent harm to the fetus. | Women | HTA+(contemplating) pregnancy |

| ADA24 | Combinations of ACEi and ARBs and combinations of ACE inhibitors or ARBs with direct renin inhibitors should not be used. | Adults | DM2 |

| Do not discontinue renin-angiotensin system blockade for increases in serum creatinine (≤30%) in the absence of volume depletion. | |||

| An ACE inhibitor or an ARB is not recommended for the primary prevention of CKD | DM2 who have normal BP, normal UACR (<30mg/g creatinine), and normal eGFR | ||

| Heart rate control | |||

| ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS20 | Dronedarone should not be used for long-term rate control. | Adults | Permanent atrial fibrillation with risk factors for cardiovascular events |

| CCS/CHRS26 | Atrial Fibrillation+Heart Failure | ||

| AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA17 | The use of beta-blocker therapy is not beneficial in reducing MACE, in the absence of another primary indication for beta-blocker therapy. | Adults | CCD without previous MI or LVEF≤50% |

| ESC/EACTS28 | Antiarrhythmic drugs are not recommended | Adults | Patients with permanent Atrial fibrillation under rate control and in patients with advanced conduction disturbances unless antibradycardia pacing is provided. |

| ESH16 | Abrupt discontinuation of pre-existing therapy with BBs or centrally acting agents (e.g. clonidine) is potentially harmful and is not recommended. | Adults | HTA |

| BBs should usually not be combined with non-DHP CCBs (e.g. diltiazem or verapamil)- | |||

| BB or non-DHP should be not initiated. | HTA+very low heart rate (<50 beats per min) | ||

| Other | |||

| ESH16 | It is not recommended to initiate anticancer therapy | Adults | Cancer+uncontrolled hypertension and BP values ≥180mmHg for systolic and/or ≥110mmHg for diastolic BP |

| AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA17 | Use of sympathomimetic weight loss drugs is potentially harmful. | Adults | CCD |

| Chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should not be used because of increased cardiovascular and bleeding complications | |||

| High dose glucocorticoids should not be used long term if alternative therapies are available because of increased cardiovascular risk. | CCD and rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Women should not receive systemic postmenopausal hormone therapy because of a lack of benefit on MACE and mortality, and an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. | Women | CCD | |

| ESVS23 | Hormone replacement therapy with estrogen or progestin is not recommended for prevention of cardiovascular disease. | Postmenopausal | |

| Prostanoids are not recommended to improve walking distance | Adults | Intermittent claudication | |

| ESC22 | SSRIs, SNRIs, and tricyclic antidepressants are not recommended | Adults | Heart Failure+major depression |

| ESC27 | When clopidogrel is used, omeprazole and esomeprazole are not recommended for gastric protection | DM2 | |

| AHA/ASA21 | Treatment with antibiotics for chronic infections as a means to prevent stroke is not recommended | Adults | – |

ACEi: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors; AKI: acute kidney injury; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; BB: beta-blockers; BP: blood pressure; CCBs: calcium channel blocking agents; CCD: coronary cardiovascular disease; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HF: heart failure; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events; MI: myocardial infarction; non-DHP: non-dihydropyridine agents; eGFR: serum creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate; RAS blocker: Renin–angiotensin-system blockers; UACR: urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRIs: serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

A total of 98 low-value or unnecessary treatment recommendations were identified (68.8% of all recommendations). Of these, 28.6% referred to antithrombotic treatment, 27.6% to lipid-lowering treatment, 24.5% to antihypertensive treatment, 7.1% to heart rate control treatment, 2.0% to antidiabetic treatment, and 10.2% to other treatments.

DiscussionA comprehensive and updated narrative review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus documents in vascular prevention published in English was conducted. All guidelines explicitly mentioning low-value practices or Do Not Do recommendations were synthesized. There are few low-value practices related to lifestyle, mainly involving supplements. Regarding alcohol consumption, it should not be recommended as it increases vascular risk and the risk of other diseases, including cancer. Regarding diagnostic tests, guidelines agree that calculating vascular risk in young healthy individuals without vascular risk factors (men<40 years, and women<50 years) or in populations already considered at high or very high risk (diabetes, familial hypercholesterolemia, chronic kidney disease, or vascular disease) is of low value, as recommended in the Spanish interdisciplinary committee for vascular prevention (CEIPV) commentary on the 2021 European cardiovascular prevention guidelines.54 However, it should be considered to evaluate risk in young women with a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as hypertensive disorders, preterm birth, gestational diabetes, or placental abruption.55 In healthy populations, performing ECG as a systematic screening method for atrial fibrillation or risk markers (such as genetic tests or specific biomarkers) is also not recommended, as there is still no robust evidence indicating an improvement in risk prediction. A recent study shows that adding biomarkers like highly sensitive cardiac troponin, natriuretic peptides, or C-reactive protein adds little to traditional risk factors for risk prediction.56 There is controversy in the guidelines about using coronary calcium. While some guidelines, like the ESC22 and CCS,31 suggest that it might be considered in individuals with intermediate risk (but not in low-risk, high-risk individuals, or those on statin therapy), other guidelines (PEER19) do not recommend its use. The CEIPV commentary mentions coronary calcium or, alternatively, carotid plaque as important risk modifiers, but does not make an explicit recommendation on this matter.54

In primary care, surely due to a matter of resources and costs, the generalized determination of coronary calcium in asymptomatic patients with intermediate risk is not contemplated. It is also not recommended to routinely determine lipid fractions such as apolipoprotein B or liproprotein (a) (Lp(a)). However, a consensus of the European Atherosclerosis Society recommends determining Lp(a) at least once in adults to identify those at high cardiovascular risk because there is evidence from observational and genetic studies of the association of high Lp (a) levels and an increase in vascular morbidity and mortality.22 In future CEIPV documents, the new evidence on these lipoproteins should be reviewed and a recommendation made in this regard.

Regarding abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening, guidelines agree that it should not be done in men under 65 or over 75 years old, nor in women. Some guidelines are more restrictive,42 recommending screening only in male smokers aged 65–75 years; other guidelines recommend screening for all men aged 65–80 years,32 while some suggest screening for all men over 65, regardless of smoking history.35 A recent publication from the European Vascular Surgery Guidelines on AAA management57 recommends abdominal ultrasound for high-risk patients, including those with a family history of AAA, other peripheral aneurysms, organ transplant history, male smokers or ex-smokers over 65, and all men over 65. A health technology assessment report from the Health Quality and Assessment Agency of Catalonia (AQuAS)58 concluded that AAA screening is an intervention that could reduce overall mortality and aneurysm-specific mortality in men over 65 years of age and increase its detection, and that the evidence is very uncertain for women over 65 years of age, yet some guidelines36 recommend AAA screening in women over 65 years of age and with a history of smoking. In Spain, especially in the field of primary care, AAA screening is not a practice that is being carried out in a systematic and widespread manner, and the CEIPV does not make a recommendation in this regard.

In the therapeutic field, guidelines generally do not recommend the use of antiplatelet drugs (aspirin) in primary prevention of vascular disease,18,21,30,43 nor the use of aspirin or clopidogrel alone for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation patients. The CEIPV does not make an explicit recommendation, though one of the societies within the CEIPV (semFYC through the Spanish program for prevention and health promotion) clearly states that aspirin should not be used systematically in primary prevention, including for individuals with diabetes.59 Some guidelines recommend that its use could be considered in patients with diabetes or high or very high vascular risk.22 Similarly, the use of anticoagulants is not recommended in patients with atrial fibrillation and at low risk of cerebrovascular disease in the next 12 months, especially those with a CHA2DS2-VASc 0 (men) or 1 (women). It is also not recommended to use doses of direct anticoagulants lower or higher than those recommended by scientific evidence for each of these drugs.

Regarding lipid-lowering treatment, there are discrepancies between the guidelines. One guideline19 does not recommend initiating statin therapy in individuals over 75, nor does it recommend assessing vascular risk or performing lipid measurements once lipid-lowering treatment begins. It also suggests avoiding non-statin medications for primary prevention due to insufficient evidence for reducing vascular morbidity and mortality, except for specific cases like familial hypercholesterolemia. Another guideline18 does not recommend the use of nicotinic acid, resins, fibrates, omega-3 fatty acids (except high doses of icosapent ethyl in certain cases), or plant sterols in primary or secondary prevention for patients with dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, or diabetes. The CEIPV has adopted a very clear position, endorsed by all societies within it. It is recommended to use the SCORE2-OP tool for those over 70 to evaluate whether lipid-lowering treatment should be started. In these patients, the evidence for starting statins is uncertain, as they are likely to be at high or very high vascular risk, and factors like renal insufficiency or potential drug interactions should be considered. If statins are used, it is better to start with low doses. High-intensity statins are recommended in very high-risk people or people with vascular disease, and if LDL-C goals are not achieved, ezetimibe should be added, and if goals are still not achieved, a PCSK9 inhibitor should be added. The first option in this group of patients could be to use non-maximum doses of statins (atorvastatin 40mg or rosuvastatin 10mg) associated with ezetimibe to facilitate the achievement of therapeutic objectives with better tolerance and adherence. The CEIPV also recommends adding n−3 fatty acids, specifically icosapent ethyl 2×2g/day, to statin treatment in high or very high risk patients with mild or moderate hypertriglyceridemia (from triglyceride levels greater than 150mg/dL). It is also recommended to perform lipid determinations once treatment has started to assess whether therapeutic objectives are achieved.54

European cardiovascular prevention guidelines also recommend using ezetimibe when statins cannot be prescribed or combining statins at lower doses with ezetimibe to prevent toxicity or improve statin effects.22 Bempedoic acid has also shown effectiveness in statin-intolerant patients, both in primary and secondary prevention.60,61 Both medications are covered by the national health system. On the other hand, some guidelines recommend not suspending lipid-lowering treatment in patients with dyslipidemia and some alteration such as increased blood glucose, cognitive problems or being of advanced age.18,19

Beta-blockers are not recommended for patients with chronic coronary disease who have not had a previous myocardial infarction or do not have a left ventricular ejection fraction of 50% or lower.17 Results from a population-based cohort study using a Swedish registry suggest that beta-blocker therapy one year after a myocardial infarction does not improve cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.62 A recent randomized, open-label clinical trial in patients with preserved ejection fraction following myocardial infarction showed no significant differences in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.63

Another low-value practice is the use of antidepressants in heart failure patients.22 This recommendation is based on a meta-analysis of 8 studies, which showed that the use of antidepressants was associated with increased total mortality risk (relative risk – RR=1.27; 95% confidence interval – CI=1.21–1.34) and cardiovascular mortality risk (RR=1.14; 95% CI=1.08–1.20) in heart failure patients, regardless of the antidepressant type or whether the patients had been diagnosed with depression.64

ConclusionThis review identified 141 recommendations for low-value practices in vascular prevention. More and more guidelines explicitly describe diagnostic or pharmacological activities of low value or Do Not Do Class III or Recommendation D, which are described as procedures that are not indicated due to being unhelpful, ineffective, or in some cases, harmful. Some guidelines agree on the recommendations, while others show clear discrepancies, illustrating the uncertainty of scientific evidence and differing interpretations.

FundingThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

For their contribution in revising the article to Soledad Justo Gil (Área de Prevención. Subdirección General de Promoción de la Salud y Prevención. Dirección General de Salud Pública y Equidad en Salud. Ministerio de Sanidad), Carla A. Dueñas Cañas and Rebeca Padilla Peinado (Estrategia en Salud Cardiovascular y GuíaSalud, respectivamente. Subdirección General de Calidad Asistencial. Dirección General de Salud Pública y Equidad en Salud. Ministerio de Sanidad).