The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vulnerability of particular patient groups to SARS-CoV-2 infection, including those with cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and intestinal dysbiosis. COVID-19 affects the gut, suggesting diet and vitamin D3 supplementation may affect disease progression.

AimsTo evaluate levels of Ang II and Ang-(1–7), cytokine profile, and gut microbiota status in patients hospitalized for mild COVID-19 with a history of cardiovascular disease and treated with daily doses of vitamin D3.

MethodsWe recruited 50 adult patients. We screened 50 adult patients and accessed pathophysiology study 22, randomized to daily oral doses of 10,000IU vitamin D3 (n=11) or placebo (n=11). Plasma levels of Ang II and Ang-(1–7) were determined by radioimmunoassay, TMA and TMAO were measured by liquid chromatography and interleukins (ILs) 6, 8, 10 and TNF-α by ELISA.

ResultsThe Ang-(1–7)/Ang II ratio, as an indirect measure of ACE2 enzymatic activity, increased in the vitamin D3 group (24±5pg/mL vs. 4.66±2pg/mL, p<0.01). Also, in the vitamin D3-treated, there was a significant decline in inflammatory ILs and an increase in protective markers, such as a substantial reduction in TMAO (5±2μmoles/dL vs. 60±10μmoles/dL, p<0.01). In addition, treated patients experienced less severity of infection, required less intensive care, had fewer days of hospitalization, and a reduced mortality rate. Additionally, improvements in markers of cardiovascular function were seen in the vitamin D3 group, including a tendency for reductions in blood pressure in hypertensive patients.

ConclusionsVitamin D3 supplementation in patients with COVID-19 and specific conditions is associated with a more favourable prognosis, suggesting therapeutic potential in patients with comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and gut dysbiosis.

La pandemia de COVID-19 ha puesto de relieve la vulnerabilidad de determinados grupos de pacientes a la infección por SARS-CoV-2, incluidos aquellos con enfermedades cardiovasculares, hipertensión y disbiosis intestinal. El COVID-19 afecta el intestino, lo que sugiere que la dieta y los suplementos de vitamina D3 pueden afectar la progresión de la enfermedad.

ObjetivosEvaluar los niveles de Ang II y Ang-(1-7), perfil de citoquinas y estado de la microbiota intestinal en pacientes hospitalizados por COVID-19 leve con antecedentes de enfermedad cardiovascular y tratados con dosis diarias de vitamina D3.

MétodosReclutamos 50 pacientes adultos. Examinamos a 50 pacientes adultos y accedimos al estudio de fisiopatológico de 22, asignados aleatoriamente a dosis orales diarias de 10.000 UI de vitamina D3 (n=11) o placebo (n=11). Los niveles plasmáticos de Ang II y Ang-(1-7) se determinaron mediante radioinmunoensayo, TMA y TMAO se midieron mediante cromatografía líquida, y las interleucinas (IL) 6, 8, 10 y TNF-alfa mediante ELISA.

ResultadosLa relación Ang-(1-7)/Ang II, como medida indirecta de la actividad enzimática ACE2, aumentó en el grupo de vitamina D3 (24±5pg/mL vs. 4,66±2pg/mL, p<0,01). Además, en los tratados con vitamina D3, hubo una disminución significativa de las IL inflamatorias y un aumento de los marcadores protectores, como una reducción sustancial de TMAO (5±2moles/dL frente a 60±10moles/dL, p<0,01). Además, los pacientes tratados experimentaron una menor gravedad de la infección, requirieron menos cuidados intensivos, tuvieron menos días de hospitalización y una tasa de mortalidad reducida. También, se observaron mejoras en los marcadores de la función cardiovascular en el grupo de vitamina D3, incluida una tendencia a la reducción de la presión arterial en pacientes hipertensos.

ConclusionesLa suplementación con vitamina D3 en pacientes con COVID-19 y afecciones específicas se asocia con un pronóstico más favorable, lo que sugiere un potencial terapéutico en pacientes con comorbilidades como enfermedad cardiovascular y disbiosis intestinal.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected millions of people worldwide, and recently, it has been observed that certain patient groups are at an increased risk of developing severe complications due to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Indeed, one of the main problems of this disease is its poor prognosis for some predisposed populations. For this reason, enormous efforts have been made to avoid or mitigate its impact and harmful consequences for health. In this regard, many factors are known to be associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19, such as old age, obesity, ethnicity, male sex, and pre-existing conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure and, more recently, gut dysbiosis.1,2 In close connection, COVID-19 is a disease that can affect multiple systems, some of which share a common denominator alteration at the level of the gut microbiota, especially the immune system.3 This leads us to focus on analyzing the roles of the microbiota in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 through the gut-lung axis.

In this regard, dysbiosis of the commensal intestinal microbes and their metabolites, as well as the expression and activity of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the intestine, could influence the host immune system in patients with COVID-19.4,5

Parallelly and closing a vicious circle, it is known that older adults and people diagnosed with comorbidities (hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, etc.) are more susceptible to alterations in the intestinal flora, SARS-CoV-2 infection, and death.6 Therefore, diet is an essential factor in modulating the state of the intestinal microbiome, where intervention with critical nutrients could improve the course of inflammatory-based diseases such as COVID-19.7 Robust evidence about the most essential nutrients which can be considered for COVID-19 management are vitamin C, vitamin A, folate, zinc, probiotics, and vitamin D.8

Vitamin D deficiency, a critical micronutrient with immunomodulatory properties, has been widely described as another serious factor potentially involved in the increased risk of developing severe forms of COVID-19.9 Moreover, it has been shown that vitamin D is a crucial regulator of COVID-19 infection in the presence of comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain neurological disorders. Factors such as sex, latitude, nutrition, demographics, pollution, and intestinal microbiota justify further research on vitamin D supplements.10–12 However, its potential benefits in COVID-19 are still unclear.

Due to the above, it was proposed as a working hypothesis that treatment with vitamin D in COVID-19-positive patients and with cardiovascular comorbidities such as high blood pressure could show a better evolution of the infectious process due to the reversal of immunological/inflammatory markers consistent with the restoration of the intestinal microbiome and its main comorbidity, high blood pressure.

Material and methodsEthics statementThe Ethics Committee of the Provincial Council for Research Ethical Evaluation and the Provincial Health Research Registry approved the study in June 2021 (reference 89/2021). The local ethics committees of the participating institutions approved the study protocol before the trial at each site. The work described has been carried out following The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association and with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Patients, randomization and interventionWe designed a randomized, double-blind, sequential, placebo-controlled study in two centres (Clínica Sanatorio Mitre and Clínica de Cuyo, Mendoza, Argentina). The protocol and informed consent were approved by the Provincial Council for Research Ethical Evaluation and the Provincial Health Research Registry (Res. 89/21). The trial was conducted between August 2021 and June 2022. We initially included 50 adult patients. From this first cohort, only those who met the following inclusion criteria were enrolled: SARS-CoV-2 confirmed infection by RT-PCR; hospital admission at least 24h before; expected hospitalization in the same site ≥10 days; oxygen saturation ≥90% (measured by pulse oximetry) breathing ambient air; age ≥18 years or at least one of the following conditions: hypertension; cardiovascular disease (history of myocardial infarction, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, coronary artery bypass grafting or valve replacement surgery); and body mass index >25 and <30; willingness to sign informed consent. The exclusion criteria: age <18 years; women; requirement for a high dose of oxygen (>5L/min) or mechanical ventilation (non-invasive or invasive); history of chronic kidney disease requiring hemodialysis or chronic liver failure; inability for oral intake; regular supplementation with pharmacological vitamin D3; known allergy to study medication; and any conditions at the discretion of investigator impeding to understand the study and give informed consent.

As a result, only 22 patients met the conditions to access the specific study, and after signing informed consent, patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) as a daily oral dose of 10,000 IU (11 patients, vitamin D3) of cholecalciferol soft gel capsules or matching placebo (11 patients, placebo). Both vitamin D3 and placebo were administered for 10 consecutive days. Serum concentrations of interleukins and cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α), 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-OH VitD), angiotensin [Ang II, Ang-(1–7)], trimethylamine (TMA) and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) were measured, both pre-and post-treatment, in each of the patients. Serum samples were maintained at −80°C until parameters quantification.

Parallel, routine biochemical analysis was determined, and clinical information was collected, including demographic data, comorbidities, and concomitant medications. Then, data were compared between both groups to evaluate the association between vitamin D3 supplementation and disease prognosis in terms of severity of infection, need for intensive care, days of hospitalization, and mortality.

25-Hydroxyvitamin D measurementSerum 25-OH VitD levels were determined, in a central laboratory, quantitatively by chemiluminescence immunoassay [A98856, Access 25(OH) Vitamin D Total, Beckman Coulter Inc., USA].13

Ang II and Ang-(1–7) levels measurementWith minimal adaptations, the procedures corresponded to those previously reported by Brosnihan and colleagues, who used the radioimmunoassay and labelled angiotensin technique.14 As a routine procedure, each sample was corrected for each recovery. For more details, please look at our previous publication, where we determined angiotensin in another protocol with positive COVID-19 patients.15

ILs levelsThe ILs levels were measured by commercially available sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) following the manufacturer's instructions. The following ELISA kits were employed: human IL-6 (BD Biosciences cat. 555220); human IL-8 (BD Biosciences cat. 555224); human IL-10 (BD Biosciences cat. 555157), and human TNF-α (BD Biosciences cat. 550610).

Serum TMA and TMAO levelsAs previously reported,16 TMA and TMAO were determined by liquid chromatography coupled to the triple-quadrupole mass spectrometry technique, using d9-TMA and d9-TMAO as internal standards. The calibration curve was generated with standards to quantify serum TMAO and TMA levels.

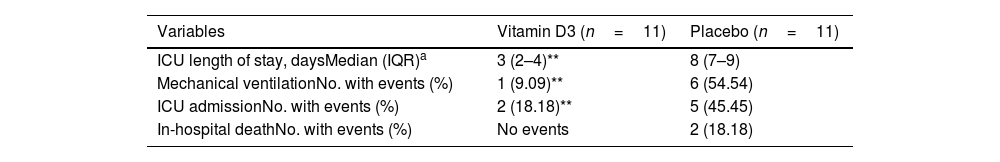

Statistical analysisFor the statistical analysis the Student's t-test was used to compare paired and unpaired variables in the follow-up of randomized groups. The analysis showed clear equivalence between the treated and untreated groups (as indicated in Table 1). Significant changes were observed in the evolution of continuous variables before and after treatment within each group, for both vitamin D3 and Placebo (as demonstrated in Tables 2 and 3). Furthermore, the evolution of the patients in the study's endpoints was carefully examined for each group (as outlined in Table 4). A p<0.05 was considered to be significant. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.

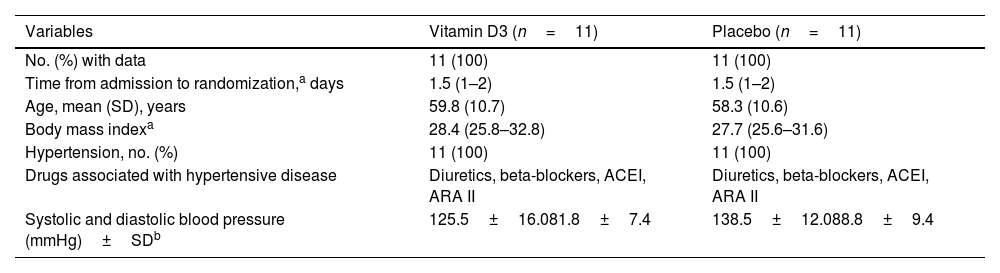

Participant's characteristics at the end of treatment.

| Variables | Vitamin D3 (n=11) | Placebo (n=11) |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) with data | 11 (100) | 11 (100) |

| Time from admission to randomization,a days | 1.5 (1–2) | 1.5 (1–2) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 59.8 (10.7) | 58.3 (10.6) |

| Body mass indexa | 28.4 (25.8–32.8) | 27.7 (25.6–31.6) |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 11 (100) | 11 (100) |

| Drugs associated with hypertensive disease | Diuretics, beta-blockers, ACEI, ARA II | Diuretics, beta-blockers, ACEI, ARA II |

| Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)±SDb | 125.5±16.081.8±7.4 | 138.5±12.088.8±9.4 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

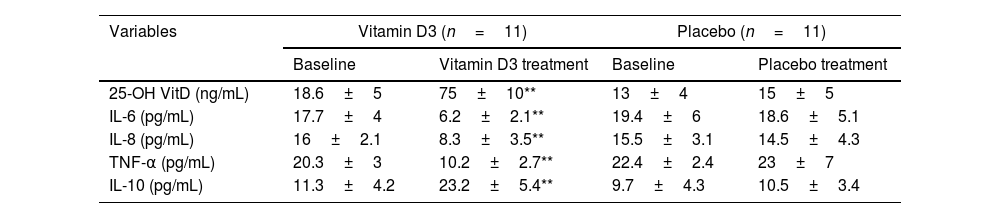

Effects of vitamin D3 supplementation on vitamin D status and serum levels of interleukins.

| Variables | Vitamin D3 (n=11) | Placebo (n=11) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Vitamin D3 treatment | Baseline | Placebo treatment | |

| 25-OH VitD (ng/mL) | 18.6±5 | 75±10** | 13±4 | 15±5 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 17.7±4 | 6.2±2.1** | 19.4±6 | 18.6±5.1 |

| IL-8 (pg/mL) | 16±2.1 | 8.3±3.5** | 15.5±3.1 | 14.5±4.3 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 20.3±3 | 10.2±2.7** | 22.4±2.4 | 23±7 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 11.3±4.2 | 23.2±5.4** | 9.7±4.3 | 10.5±3.4 |

Vitamin D status and serum levels of interleukins at baseline and post-treatment in placebo and vitamin D treated groups. The results are shown as mean±SEM.

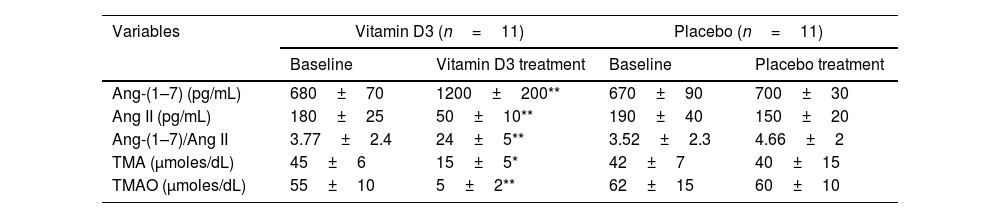

Effects of vitamin D3 supplementation on plasma RAS components, TMA and TMAO levels.

| Variables | Vitamin D3 (n=11) | Placebo (n=11) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Vitamin D3 treatment | Baseline | Placebo treatment | |

| Ang-(1–7) (pg/mL) | 680±70 | 1200±200** | 670±90 | 700±30 |

| Ang II (pg/mL) | 180±25 | 50±10** | 190±40 | 150±20 |

| Ang-(1–7)/Ang II | 3.77±2.4 | 24±5** | 3.52±2.3 | 4.66±2 |

| TMA (μmoles/dL) | 45±6 | 15±5* | 42±7 | 40±15 |

| TMAO (μmoles/dL) | 55±10 | 5±2** | 62±15 | 60±10 |

RAS components, TMA and TMAO levels at baseline and post-treatment in placebo and vitamin D treated groups. The results are shown as mean±SEM.

Clinical evolution parameters.

As previously mentioned, 22 participants were included in the study between August 2021 and June 2022 at two research sites in Mendoza, Argentina. The same were randomly assigned to vitamin D3 (n=11) and placebo (n=11).

The mean age of all patients was 59.05 (10.66) years, all men by inclusion criterion. Risk factors included hypertension in 22 (100%) patients, overweight in 22 (100%), chronic respiratory disease in 4 (18.18%) patients, and cardiovascular disease in 10 (45%). The median time from hospital admission to randomization was 1.5 (IQR 1.0–2.0) days. Diuretics, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin II (AT1) receptor antagonists were included in the medications given to control cardiovascular disease and hypertension.

Concerning the general characteristics of the patients, randomization was adequate since we did not find significant differences between the groups (vitamin D3 vs. placebo) at the end of the 10 days of treatments. In this sense, it is worth clarifying that the group of patients with vitamin D3 required lower doses of the cardiovascular drugs (Table 1).

As expected, we established significantly elevated plasma 25-OH VitD levels in patients treated for 10 days with vitamin D3 compared to those in the placebo group (75±10ng/mL vs. 15±5ng/mL, p<0.01). Regarding pro-inflammatory markers (IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α), in all cases, it was found that patients treated with the placebo presented significantly elevated values (p<0.01), and in contrast, these values were substantially lower in the group of patients treated with vitamin D3 for 10 days. In contrast, IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, experienced a significant increase in patients treated for 10 days with vitamin D3 compared to those treated with placebo (p<0.01) (Table 2). To considerate, the baseline data of all patients at the beginning of the protocol did not differ significantly from each other (vitamin D3 vs. placebo); in fact, the vitamin D status (as 25-OH VitD) was below the values considered normal (30ng/mL) while the pro-inflammatory cytokines were elevated and IL10 was low (Table 2).

Of interest for this report, we determined renin–angiotensin system (RAS) pathways (Ang 1–7, Ang II and Ang 1–7/Ang II ratio). The data showed evident activation (pressor arm) in patients treated with the placebo, while those receiving vitamin D3 demonstrated significant downregulation (depressor arm) (p<0.01). To highlight, when we evaluated the status of the intestinal microbiome through plasma products such as TMA and TMAO, we found a significant increase in TMAO in the group of patients not treated with vitamin D3 (placebo) compared to the treated (60±10μmoles/L vs. 5±2μmoles/L, p<0.01) (Table 3). In the same way, as mentioned for vitamin D and cytokine status, no significant differences were found at the beginning of the protocol (vitamin D3 vs. placebo) when the angiotensin signalling pathways and the status of the intestinal microbiome were compared. We only highlight that all patients presented RAS activation and intestinal dysbiosis (Table 3).

When it was evaluated whether daily supplementation with vitamin D3 versus placebo impacted routine biochemical parameters, it was concluded that none showed significant changes (hemogram, calcium, creatinine, etc.).

Finally, the patient's clinical symptoms showed that those treated with vitamin D3 manifested a lower severity of the infection, with a significant reduction in the need for intensive care, fewer days of hospitalization and an apparent lower mortality rate (Table 4). Additionally, seen in the vitamin D3 group had a trend of lower blood pressure (Table 1).

DiscussionThe results of our study provide additional compelling evidence for the potential benefits of vitamin D3 supplementation in COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular comorbidities, such as overweight, history of cardiovascular disease and hypertension. In addition, these patients showed a better evolution of the infectious process by reversal of immunological/inflammatory markers consistent with the restoration of the intestinal microbiome, mitigating a complex pathophysiological vicious circle. In agreement, several works highlight the close correlation between gut microbiota alterations and the cytokine response in patients with COVID-19 during hospitalization, as is the case of Mizutani et al., who emphasize the need to understand how pathology relates to the gut environment, including the temporal changes in specific gut microbiota observed in COVID-19 patients.17 In this sense, the bacterial phenotypes that characterize patients with COVID-19 have already been identified.18 Likewise, dietary and pharmacological intervention proposals have been made to restore this intestinal dysfunction and its systemic inflammatory impact.7,8 To highlight, and of particular interest for our present work, poor 25-OH VitD levels have long been associated with greater severity, duration, and death in COVID-19-positive patients. The evidence refers to alterations in the regulation of the intestinal microbial community as well as immune modifications of the patient. Therefore, supplementation of essential nutrients – such as vitamin D3 – improves the intestinal exposome, raising the defenses against acute or post-acute COVID-19 in the intestine–lung axis.19

Concerning inflammatory markers, our study shows that supplementation with vitamin D3 for 10 days may benefit the anti-inflammatory response in patients with COVID-19. Specifically, patients treated with vitamin D3 had significantly lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, than those treated with placebo. In contrast, they had substantially higher levels of IL-10. These findings are consistent with recent works that bring together robust evidence of the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties promoted by vitamin D3 in patients with COVID-19.10 Moreover, we add new evidence on the importance of 25-OH VitD levels and their correlation with better evolution prognosis in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Unlike what was previously reported by our laboratory,15 all the patients enrolled in the present study had vitamin D values below what was considered optimal (30–50ng/mL), and after the established treatment, they reached significantly elevated values without manifesting of side effects (for example, normal calcium levels). Vitamin D levels (status) in the COVID-19 context were and are a topic of permanent discussion and controversy; this discrepancy could be attributed to several factors, including differences in study design, patient populations, vitamin D dosages, and baseline vitamin D levels.20 However, there are new guidelines for preventing and treating vitamin D deficiency, and they recommend and categorize them as deficiency (<20ng/mL), suboptimal status (20–30ng/mL), and optimal concentration (30–50ng/mL).21 Therefore, our patients were initially categorized as deficient with plasmatic 15±5ng/mL of 25-OH VitD levels, while after treatment, they exceeded the values recommended as optimal, reaching plasmatic 75±10ng/mL of 25-OH VitD levels. Once again, and in agreement with the literature, we have shown that treatment with high doses of oral vitamin D3 reduces risks, particularly in patients with hypovitaminosis; it should be noted that the lack of side or adverse effects reinforces the notion that the administration of 10,000IU/day of vitamin D3 for 10 days during hospitalization for COVID-19 was safe, tolerable, and beneficial, helping improve the prognosis.22

Regarding vitamin D status, a long time ago, our group reported that vitamin D deficiency was a new pandemic and impacted multiple diseases with a common denominator, alterations at the immune/inflammatory levels. This report highlighted a central fact: the RAS system's exaltation.23 The COVID-19 pandemic was announced much later (March 11, 2020), which also has a central immunological/inflammatory factor associated with RAS signalling pathways. Like a “Deja Vu”, for us, history repeats itself. Among the mechanisms proposed for COVID-19 prevention and treatment, vitamin D first appears as a hypothesis and is then used in many protocols for clinical trial studies.24 Thus, in this meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with 8128 participants, the authors conclude that vitamin D supplementation may benefit the severity of illness caused by SARS-CoV-2, particularly in deficient patients, and they propose further studies that – such as our present work – are still needed.

Parallel to differences in all inflammatory markers evaluated at the end of the 10-day treatment period, we also demonstrated significant downregulation of the RAS pathway (Ang 1–7, Ang II and Ang 1–7/Ang II ratio). Our data showed activation in patients treated with the placebo, while those receiving vitamin D3 demonstrated significant downregulation. In this sense, our results find support in what has been reported by other authors,25,26 but in addition, they add new evidence since, very recently, it has been proposed to evaluate the pressor arm as the protector and its ratio as biomarkers of prognosis and evolution in COVID-19 patients.27 In close relation, our patients who, in addition to being COVID-19 positive, were selected with cardiovascular disease criteria, particularly hypertensive, after being treated with vitamin D3 tended to reduce their blood pressure values. Strengthening our finding, Al-Kaleel and colleagues reported that vitamin D increased ACE2 expression and Ang-1–7 levels and decreased Ang II levels in plasma; therefore, it could prevent the risk of preeclampsia or hypertension in pregnant women with COVID-19.25 More specifically, on blood pressure and vitamin D, Theiler-Schwetz et al. carried out a randomized controlled trial to evaluate blood pressure in patients with low 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Similar to our findings, they described that although the antihypertensive treatment with vitamin D3 daily was ineffective, a significant trend of an inverse association between the achieved 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and systolic pressure was noted.28

In our present study, the significant downregulation of the angiotensin pressor pathway in the vitamin D3 group is a novel finding with exciting implications. This result aligns with preclinical evidence suggesting that vitamin D3 acts as a natural inhibitor of ACE2, mitigating the detrimental effects of Ang II and promoting the vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory properties of Ang 1–7.29 Consequently, this mechanism could have contributed to our patients’ better cardiovascular function and reduced inflammatory markers. As we mentioned, few studies are specific to patients with cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and related complications where any benefit of vitamin D supplementation in patients with COVID-19 is described.28 Further, given that vitamin D has significant protective effects on the cardiovascular system, including augmentation of myocardial contractility and anti-thrombotic impact,30 it is not profoundly known if vitamin D3 supplements can mitigate CVD complications associated with COVID-19. In this sense, our results provide new evidence on this critical issue because is focused on a specific population with cardiovascular comorbidities, which may provide valuable information not captured in more extensive trials.

In addition to the mechanisms discussed, a complex association between the gut microbiota and the expression of ACE2 and vitamin D in the severity and prognosis of COVID-19 has been evidenced in recent times. In this sense, experts affirm that the gut microbiome mainly allows us to predict plasma molecular mediators associated with inflammatory signalling pathways and host responses.31 In line with our expectations, when we evaluated the state of the gut microbiome through plasma products such as TMA and TMAO, we found a significant increase in TMAO in the placebo group. On the contrary, in the vitamin D3 group, TMAO levels were reduced, cytokine profiles improved, and clinical variables tended to stabilize. These findings, together with data on angiotensin signalling (ACE2) and inflammatory markers, suggest multiple approaches addressed by vitamin D3 to mitigate the severity and improve the prognosis of COVID-19, breaking a complex and dangerous vicious cycle. Therefore, it is inferred that the marked decrease in TMAO levels in the vitamin D3 group is a direct and positive consequence related to improving the intestinal microbiome. TMAO, a gut-derived metabolite linked to cardiovascular disease and inflammation, has also been implicated in COVID-19 severity. Vitamin D3 might indirectly benefit the lungs through the gut-lung axis by restoring gut microbial balance, mitigating the inflammatory cascade and improving clinical outcomes. The impact of vitamin D on improving intestinal dysbiosis through the reduction of TMAO in a murine model was previously reported.32 However, our results in context with the current state of knowledge allow us to suggest unprecedented concrete benefits of high doses of vitamin D3 in COVID-19 patients with hypertensive comorbidity and alterations of the intestinal microbiome.

Finally, while our study provides promising results, we authors recognize that some limitations must be addressed. The sample size remains relatively small, and the duration of the study may be insufficient to capture the full spectrum of long-term effects of vitamin D3. In this sense, the authors also acknowledge that sample size statistical power was not calculated. However, the size responds to inclusion and exclusion criteria, also resulting to a certain extent in controlling variables as a relative strength. Furthermore, the study population consisted only of male patients with overweight and hypertension, which limits the generalizability of the results.

Future research should focus on more extensive randomized controlled trials with diverse populations and long follow-up periods. Investigating the specific mechanisms through which vitamin D3 modulates the angiotensin pathway and gut microbiome in patients with COVID-19 could provide valuable information for future therapeutic interventions. Additionally, it would be helpful to explore possible sex differences in response to vitamin D3 supplementation. The gut microbiome varies as does CVD and susceptibility to COVID-19.

Despite limitations, our findings add to the growing body of evidence supporting the potential benefits of vitamin D3 supplementation in COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular comorbidities. Its safety profile, low cost, and potential to address multiple pathological pathways suggest that vitamin D3 could emerge as a valuable tool to mitigate the severity of COVID-19, particularly in vulnerable populations.

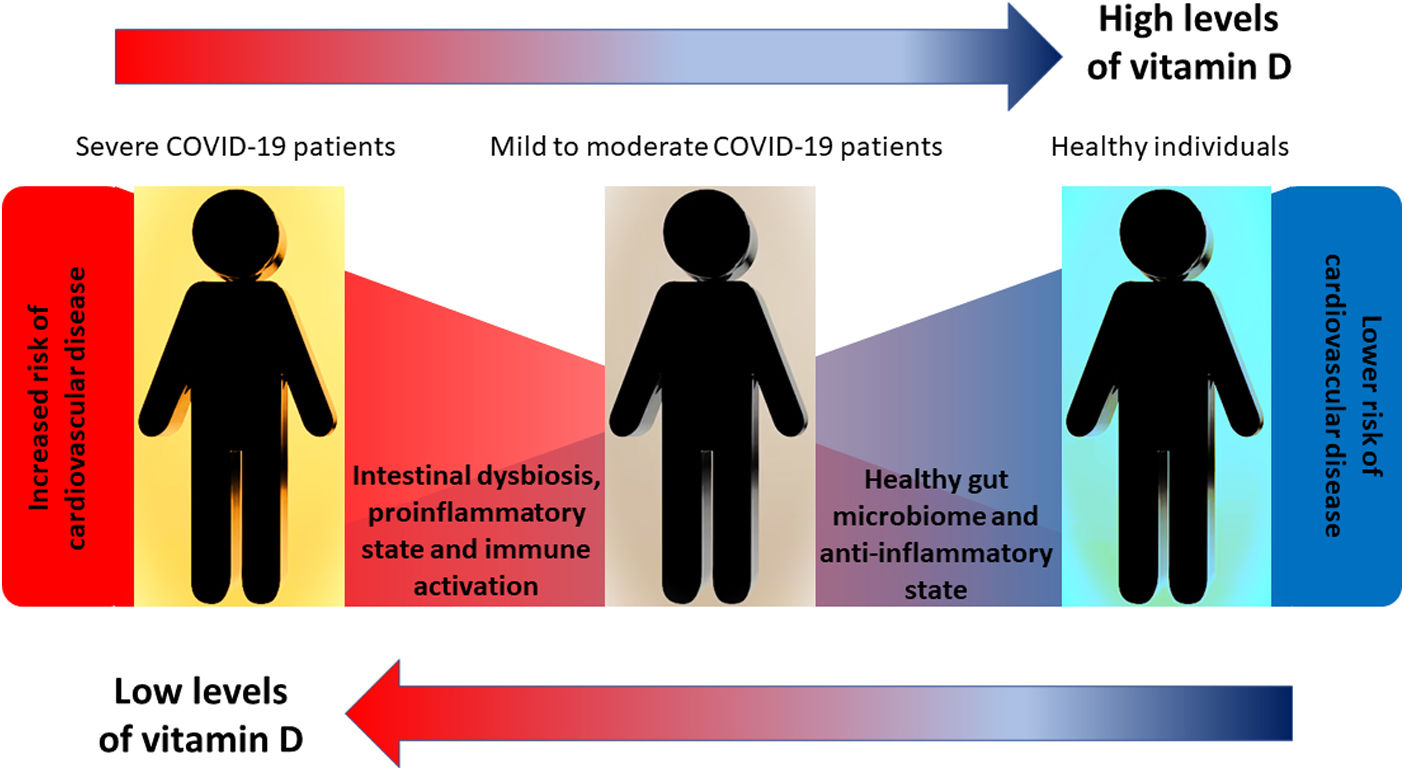

ConclusionsVitamin D supplementation in COVID-19-positive patients with cardiovascular disease, hypertension and intestinal dysbiosis is associated with a better disease prognosis, including reduced severity of infection and a reduction in the need for intensive care hospitalization and mortality. These findings suggest that vitamin D could be therapeutic in managing patients with COVID-19 and associated comorbidities, especially those with vitamin D deficiency, overweight, hypertension and intestinal dysbiosis. Fig. 1 summarizes the proposed hypothesis and the correlation with the results obtained.

Graphical overview: the figure schematically represents our central working hypothesis that proposed that treatment with vitamin D in COVID-19-positive patients and with cardiovascular comorbidities such as high blood pressure could show a better evolution of the infectious process due to the reversal of immunological/inflammatory markers consistent with the restoration of the intestinal microbiome and its main comorbidity, high blood pressure.

Raúl Lelio Sanz (data collect analysis and interpretation of the data), Federico García (data collect), Alejandro Gutierrez (data collect), Sebastián García Menendez (data collect), Felipe Inserra (data collect analysis and interpretation of the data, conception and design of the manuscript, drafting, review, approval of the submitted manuscript), León Ferder (conception and design of the manuscript), Walter Manucha (analysis and interpretation of the data, conception and design of the manuscript, drafting, review, approval of the submitted manuscript).

FundingThis work was supported by grants from the Research and Technology Council of Cuyo University (SECyT), Mendoza, Argentina, and from ANPCyT FONCyT, both of which were awarded to Walter Manucha. Grant no. PICTO Secuelas COVID-19, and IP-COVID-19-931.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsFor this work, the authors considered the basic principles of bioethics. Before the protocolization, each patient signed the informed consent. The Provincial Council for Research Ethical Evaluation and the Provincial Health Research Registry approved the protocol.

Confidentiality of the dataThe authors declare that patient data does not appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that patient data does not appear in this article. Before the protocolization, each patient signed the informed consent.

Conflict of interestsNone of the authors declare a conflict of interest with the manuscript's content.