Although calcium titanate has been proposed as a coating for biomedical applications, a characterization of tribological properties simulating human conditions has not been reported. In this work we studied friction and wear mechanism of calcium titanate coating growth onto AISI 304 steel (750nm thickness) deposited by r.f. magnetron sputtering. It was found that the wear mechanisms of the system is bone adhesion to the coating without detachment of the coating, both dry and in Hank's solution, with a friction coefficient of 0.84 ± 0.13 and 0.65 ± 0.13, respectively. The wear of the bone was more severe when using a simulated body fluid at 37°C in the pin on disk test.

Aunque el titanato de calcio ha sido propuesto como recubrimiento para aplicaciones biomédicas, no se han reportado caracterizaciones tribológicas en condiciones que simulan las condiciones del interior del cuerpo humano. En este trabajo se evalúan propiedades de fricción y mecanismos de desgaste de estos recubrimientos (de 750nm de espesor) depositados mediante r.f. magnetrón sputtering. Se encontró que el mecanismo de desgaste del sistema es adhesión de hueso al recubrimiento sin desprendimiento de la capa, tanto en seco como en solución de Hank, con coeficientes de fricción de 0.84 ± 0.13 y 0.65 ± 0.13, respectivamente. El desgaste del hueso fue más severo cuando el ensayo de pin-disco se llevó a cabo en fluido corporal simulado.

Hip prosthesis stems may be cemented or uncemented, the uncemented have four options for achieving adhesion with the surrounding tissue: by pressure, porous surface, screws or with coated surface. Joint prosthesis with hydroxyapatite coated stems have presented a big clinical success, as they increase the rate of osseointegration regarding uncemented prosthesis (Faig and Gil, 2008; Coathup et al., 200; Rokkum and Reigstad, 1999). However, in the long run this coating dissolves and detaches exposing the base metal (Porter et al., 2004), which can lead to the loosening of the prosthesis, pain in the patient, wear on the rest of the prosthesis or, in the worst case, to extensive destruction of bone tissue.

Although the calcium titanate has been studied extensively in regard to optical and luminescent properties (Moreira et al, 2009; Wang et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009), an interface layer containing calcium titanate on biomedical titanium alloys coated with hydroxyapatite has been found (Ergun et al., 2003; Kokubo et al., 2003), so that some authors have reported to have obtained calcium titanate layers by various methods on titanium and titanium alloys, such as sol-gel (Holliday and Stanishevsky, 2004), magnetron sputtering (Asami et al., 2005), ion-beam assisted deposition (Ohtsu et al., 2006), pulsed laser deposition (Ohtsu et al., 2007), hydrothermal–electrochemical method (Wiff et al., 2007), thick alkalized calcium oxidation (Ohtsu et al., 2007), and hydrothermal treatment (Park et al., 2011) for biomedical applications.

Despite the fact that most commercial prostheses are made of titanium or titanium alloys, because the material replaced for bone is expected to have a modulus equivalent to that of bone (Geetha et al., 2009), and due to their high cost and their poor tribological properties, stainless steels is still used in hip prosthesis and remains under investigation for biomedical purposes (Lundin et al., 2012; Nie, 2011; Barragán et al., 2010). Although type 304 is seldom used in biomedical implants or devices and its sensitivity to any sign of corrosion is more detectable than in 316L (Tang et al., 2006), it is used in implants such as brackets and screws. This steel also meets ASTM F138 y ASTM F139 (ASTM F138–08, 2008; ASTM F139–08, 2008) standards for steels used in biomedical applications and it is cheaper than AISI 316L which would represent a reduction in hip prosthesis cost. This is the reason for proposing here the evluation of tribological properties of AISI 304 stainless steel coated with calcium titanate for prosthesis stem applications.

It is known that due to the continuous micro-movements between the bone and the implant (Fu et al., 1998) wear femoral stem occurs (Howell et al., 1999), so it is important to know the tribological properties of the coating with respect to the bone, such as friction and wear in conditions which approach those of the human body. Therefore, this work aims to evaluate calcium titanate coated AISI 304 stainless steel by r.f. magnetron sputtering, evaluating mechanical properties of hardness and elastic modulus by nanoindentation; coefficient of friction and wear by pin-on-disc test in dry conditions at room temperature and in Hank's solution at 37 ¿C with an animal bone pin as a counterpart.

Materials and methodsThe CaTiO3 cathode used for the sputtering technique were from CaTiO3 powder with a purification of 99.9% from Super Conductor Materials, Inc. Silicon (100) and 304 stainless steel disks (diameter = 1.27 cm and thickness = 3 mm) were used as substrates. The steel was polished with sandpaper passing numbers 200 to 2000, and finally with 1 and 0.3 μm alumina solution. Prior to deposition of calcium titanate an approximately 200 nm titanium layer was deposited onto steel substrate by magnetron sputtering, during the 3 hours at a temperature of 250¿C, with a power density of the cathode fixed at 350 W.

Calcium titanate was deposited via magnetron sputtering in Ar atmosphere. Prior to the deposition, the deposition chamber was evacuated to a base pressure of 2 × 10–6 mbar and the target was sputter-cleaned for 20 min, before film growth. During the 4 hours deposition process at a temperature of 500¿C, the sputtering power density deposition of the CaTiO3 cathode was fixed at 2.47 W/cm2, the pressure in the chamber was fixed at 2 × 10–2 mbar, and the target was fixed 4.3 cm under the substrate.

The crystal structure of the films was determined by using glancing incident X-ray diffraction (GIXRD) at 2¿ incidence angle with a RIGAKU (Dmax2100) difractrometer using Co Kα radiation (λ = 1.78899 Å, 30 kV and 16 mA). The chemical composition of deposited films was performed by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) in the scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM-649 OLV SEM). The thickness of the films was measured by Scanning Electron Microscope (JEOL JSM-649 OLV). The mechanical analysis was performed via nanoindentation (ASTM E2546-07; 2007) by means of anUBIL - HYSITRON device and a diamond Berkovich tip. For each sample several series of ten indents were made and the results were averaged, since the maximal nanoindentation depth was about 10% of coating thickness.

Taking into account that these coatings are proposed for use in hip prosthesis stems a pin-on-disk test (ASTM G99-05, 2010) with animal bone ball as a counterpart was used to measure the wear resistance and the friction coefficient using a MT60 tribometer from NANOVEA™. The bone pin was prepared from a bovine metacarpal diaphysis, which was immersed in boiling water avoiding touching the bottom of the vessel to not degrade its mechanical properties. Then the soft tissue was removed mechanically by hand and the bone was immersed in a bleach-water mixture (1:5 volume) for 53 hours for further machining to a spherical geometry of 6 mm diameter. For mechanical measurement via nanoindentation specimens were embedded in plastic (Lucite, Buehler) to protect them from damage and to provide a uniform format for preparation. The sample was polished using a sequence of abrasives silicon carbide grit paper ending with 0.3 micron alumina suspension, using water as a lubricant. Each sample was indented 24 times using a Berkovich pyramidal indenter, varying the maximum load applied from 479.6 to 5995.8 μN (10 seconds of loading and 10 seconds of unloading).

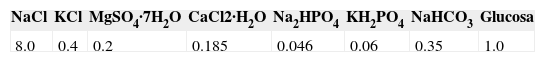

Tribological test was carried out in dry and wet conditions (three bare steel samples and three coated samples in every condition). Dry tests were carried out at room temperature and relatively humidity of 65% ± 4, wet tests, simulating body conditions (SBC), were performed using Hank's solution (Table 1) at 37¿C ± 1. The test is carried out with Hank's solution because this is, of all the available solutions, the one that most closely approximates to the composition of blood plasma (Zhanga et al., 2013). The applied load was 3 N, the distance was 200 meters at 100 rpm (test duration: 1hour, 46 minutes). A detailed characterization of the worn surfaces was performed using a Scanning Electron Microscope (JEOL JSM-649 OLV) after cleaning with acetone and water at 50¿C.

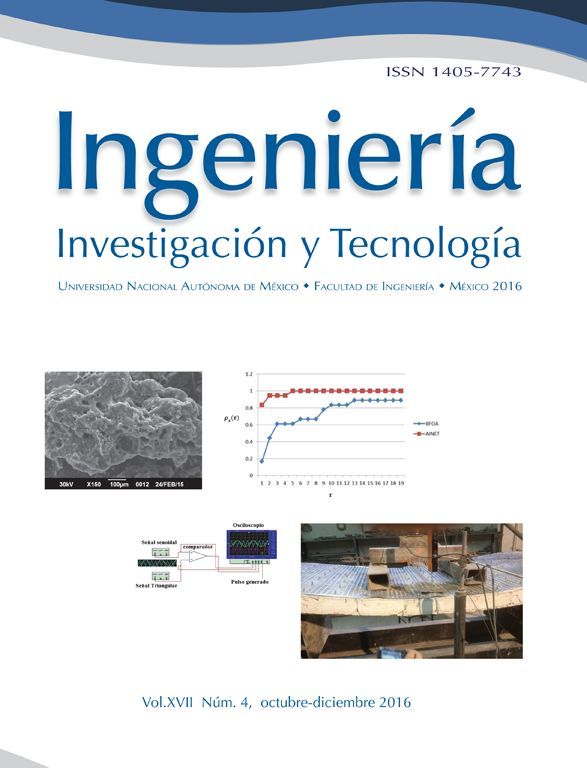

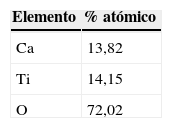

Results and discussionChemical composition, morphology and phase composition of the coatingsThe EDX spectrum of elemental composition of the coating surface, Figure 1: a) revealed that the coating contains Ca, Ti and O atoms (Si belongs to the substrate) with a Ca-Ti ratio of 0.98. Table 2 shows the elemental chemical composition. As can be seen in b), the coating obtained is homogeneous without micro-pores or particles on the surface. Finally, a thickness of 750 nm is shown in a cross sectional view c) on calcium titanate coating.

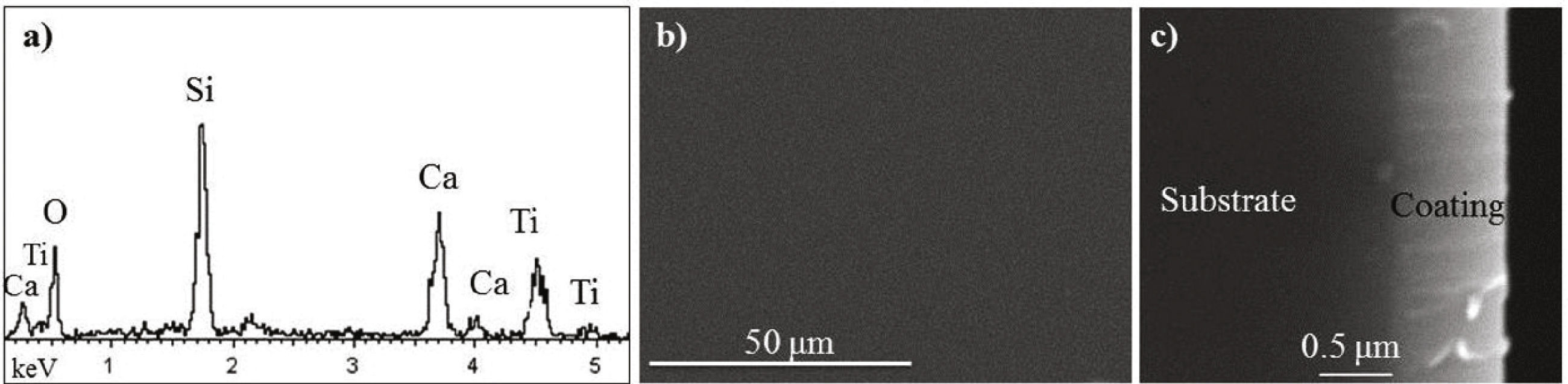

The grazing incident XRD pattern of CaTiO3 film is shown in Figure 2. This indicates that the coating exhibits polycrystalline structure with a (022) preferential orientation corresponding to Pbnm orthorhombic CaTiO3 phase at 33.293¿. The shift toward high angles (0.69 grades) at positions 33,293¿ and 40,673¿ of JCPDF 01-088-0790 card is in relation with compressive residual stress characteristics. The positions 52.827¿, 52.931¿, 64.747¿ and 64.866¿ are in agreement with JCPDF 01-082-0231 card which also corresponds to an orthorhombic Pbnm calcium titanate. The peak located at 72.779¿ is in agreement with JCPDF 00-043-0226 card, corresponding to a cubic Pm-3m calcium titanate, which is a phase that normally occur above 1300¿C (Roushown and Masatomo, 2005), and it is known that metastable phases can be formed in as-deposited thin films by physical vapor deposition whereas they are hardly seen in bulk counterparts (Krzanowski, 2004). Finally, anatase phase with (101) and (224) reflections of TiO2 was observed, in agreement with JCPDF 01-083-2243 card; and was also found a coincidence with 01-074-1226 card, in 64.647¿ position, which correspond to (311) reflection of CaO; that is because the deposition process is assumed to atomically disassemble the compound AXY, directing A, X and Y atoms toward the substrate, where they can be reassembled in multiple phases (Krzanowski, 2004), it means that a part of the material reaching the substrate is suffering the next change: CaTiO3→TiO2+CaO

The crystallinity of the coatings indicates that heating the substrate at 500¿C is appropriate for obtaining calcium titanate crystalline coatings. This is better than that reported by Naofumi Ohtsu et al. (2007) who obtained crystalline films at 600¿C.

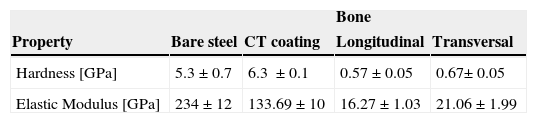

Mechanical propertiesHardnessTable 3 shows materials hardness and elastic modulus measured by nanoindentation. In all three cases the averaged uniaxial Young's moduli and hardness (in the axial and transverse directions for bone) values were computed from the experimental curves using the Oliver-Pharr theory (Oliver and Pharr, 1992). The mechanical differences in bone values (longitudinal and transversal directions) are due to structural anisotropy and are also linked to a variation in chemical composition (Rho et al., 1998).

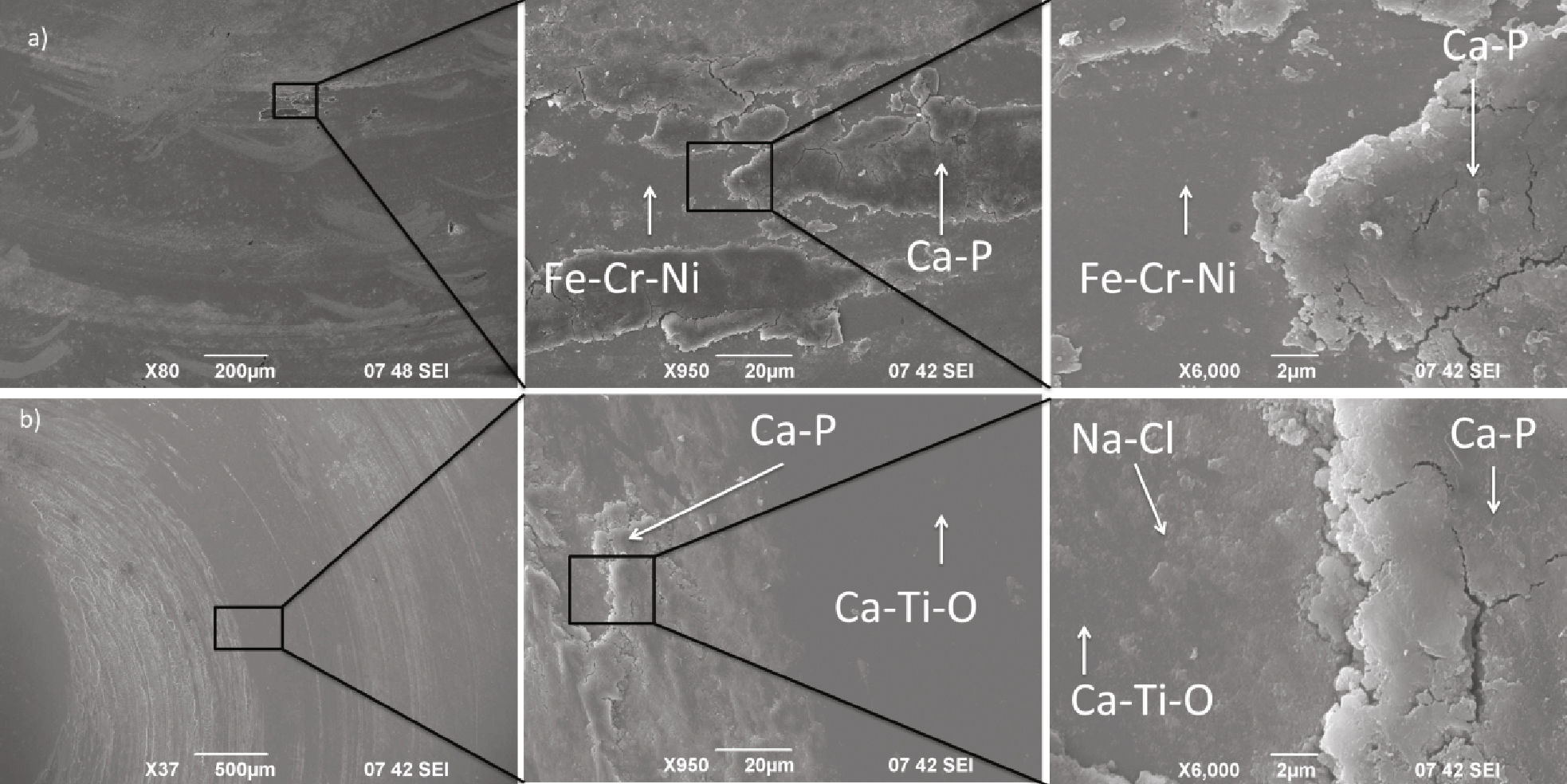

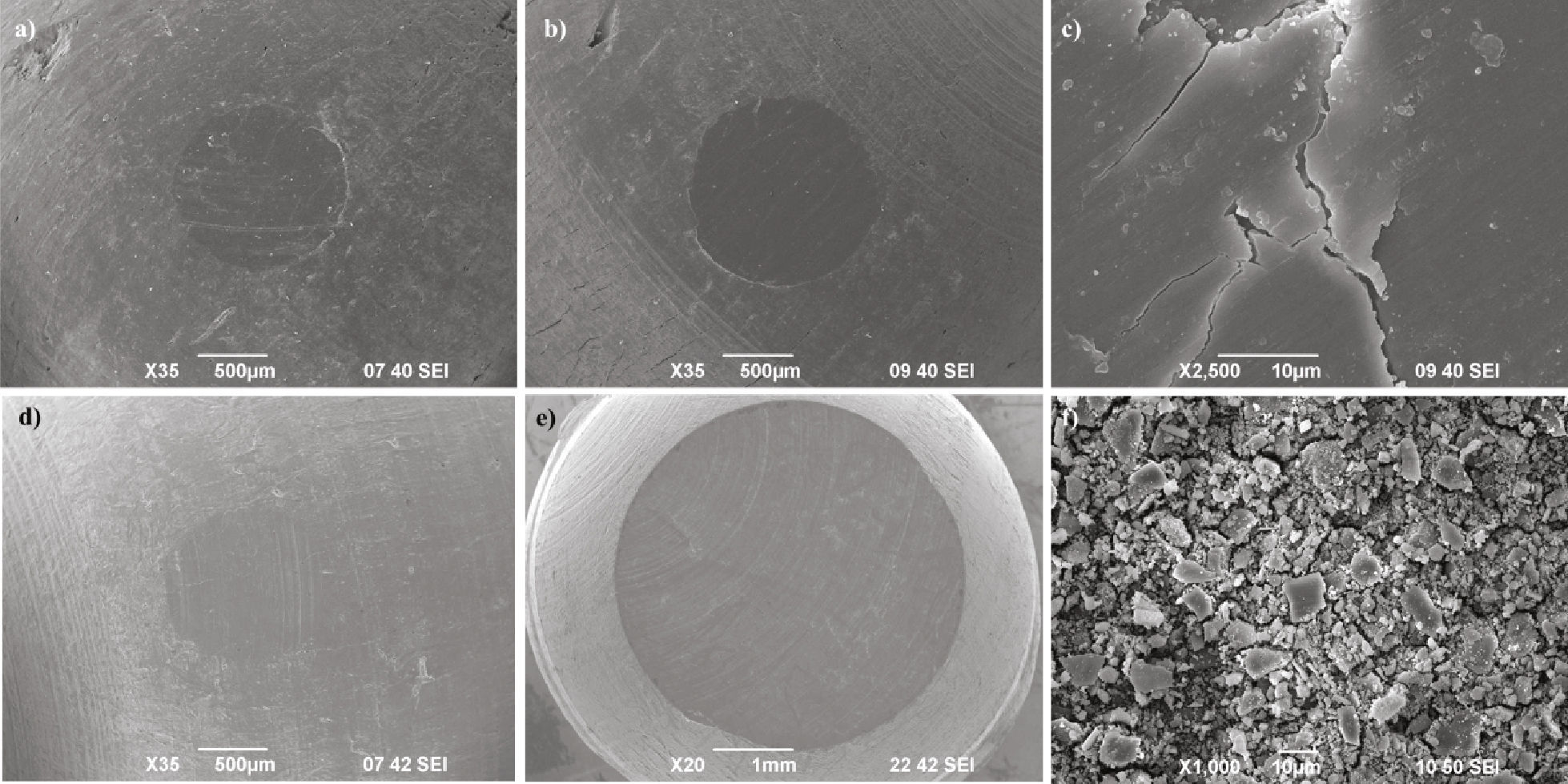

Tribological propertiesIn part a) of Figure 3 it can be seen the wear mechanisms on bare steel and the spherical counterpart bone. There are two wear mechanisms: abrasive wear and adhesive wear. Second zoom shows plow lines indicating abrasive wear likely because of some steel particle came off due to fatigue and strain hardened generated abrasion to disk. The zoom shows bone adhesion to the disk; it is also observed that adhered material fractures because of fatigue forming wear debris acting as a third body. In part b) we observe wear mechanisms of coated steel. Abrasive wear is not observed and EDX probe revealed no bare steel, so it follows that the coating maintained its integrity after testing. The only wear mecha- nism observed is adhesive and fatigue fracture of bonded bone forming wear particles. Figure 4 shows the wear mechanisms of bare steel and coated steel in Hank's solution. It can be seen that the only wear mechanisms both cases is bone adhesion, there is no abrasive wear in neither case, there is no detachment of the coating, and there is salts precipitations.

Figure 5 parts a) and b) show bone pin acting as counterpart of bare steel and coated steel, respectively, in dry test. Part c) presents how bone layers are formed due to fatigue, this layers subsequently will be bonded to the steel samples. Parts d) and e) show bone pin acting as counterpart of bare steel and coated steel, respectively, in Hank's solution test. Part f) shows the geometry of wear debris from dry test, which exhibit brittle fracture and an average size of 8 μm larger ones.

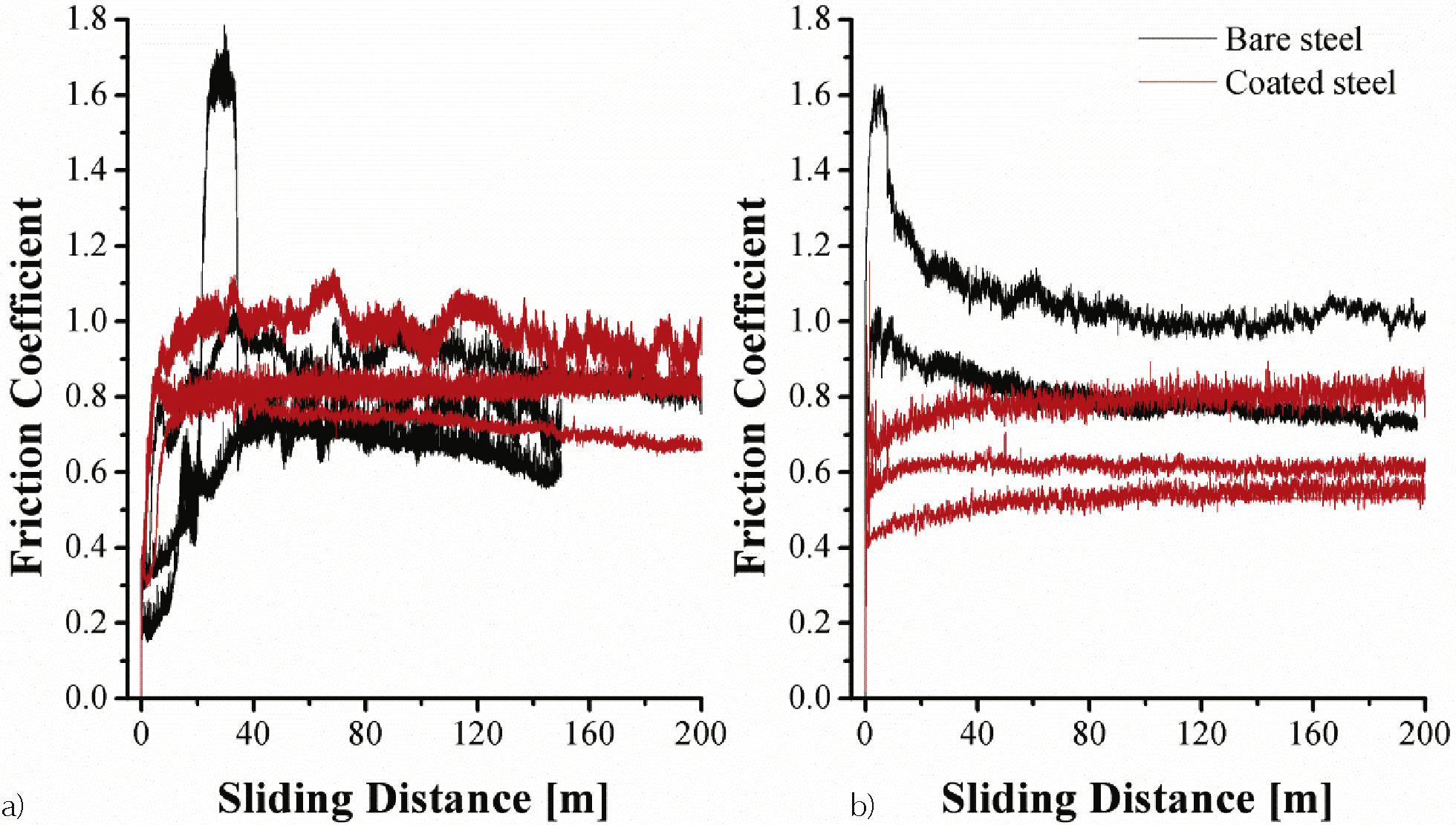

Figure 6 shows friction coefficient in function of sliding distance in pin-on-disk test. In part a) stages 1 and 2 refer to asperities deformation and contaminant removal mentioned by Holmberg and Matthews (2009) appear in small proportion in bare steel and are almost nonexistent in coated steel due to their low initial roughness and high cleanness. Stage 3 where the friction coefficient increases due to the rapid increase of wear particles trapped between the sliding surfaces is larger in bare steel than in coated steel. This could be because the coating removes more bone wear debris due to its higher hardness, as can be seen in Table 3, which rapidly increases the friction coefficient. Relative to stage 4, one of the bare steel samples does show a short interval with a friction coefficient of about 1.7 before reaching the steady state, which may be related to greater wear bone, 1.59 × 102 mm3, compared with the wear in the bone provided because of the other two samples, 0.79 × 102 mm3 and 0.76 × 102 mm3. The reason for this differences in bone wear is the bone anisotropy: its hardness in the longitudinal direction is different in the transversal direction (Rho 1998); as this orientation could not be controlled in the pins preparation of the current investigation, these may exhibit different hardness according to the area that is in contact with the disk, in this case the hardness of the pin which acted as counter-part of the steel sample in question is 50.83 ± 3,59 HV, compared with the hardness of the other two samples, 54.23 ± 2.66 HV and 69.04 ± 1.94 HV, respectively. It can also make a correlation between bone pin wear and dynamic friction coefficient of coated steel: high to low friction coefficient pin wear were 1.04 × 102 mm3, 2.53 × 102 mm3 and 2.85 × 102 mm3, whose hardness were respectively 59.77 ± 2.13 HV, 54.21 ± 3.28 HV and 43.74 ± 1.97 HV. Namely in dry conditions, volume loss of bone decreases with increasing bone hardness. At steady state it can be seen that friction coefficient of coated steel (0.84 ± 13) is on average greater than the coefficient of friction of bare steel (0.77 ± 0.11), which is related, as shown in Figure 7, with bone volume loss, 0.021 mm3 ± 0.009 mm3 for coated steel and 0.010 mm3 ± 0,004 mm3 for bare steel. It means a higher friction coefficient goes together with a higher volume loss.

Under conditions which simulate the human environment (Hank's solution at 37¿C), on the contrary, part b) of Figure 6 shows that at steady state friction coefficient of bare steel (0.89 ± 0.12) is on average greater than the friction coefficient of coated steel (0.65 ± 0.12) related with bone volume loss of 0.051 mm3 ± 0,009 mm3 and 2.82 mm3 ± 0.58 mm3, respectively, as can be seeing in Figure 7. It means, in Hank's solution, a higher friction coefficient goes together with a lower volume loss.

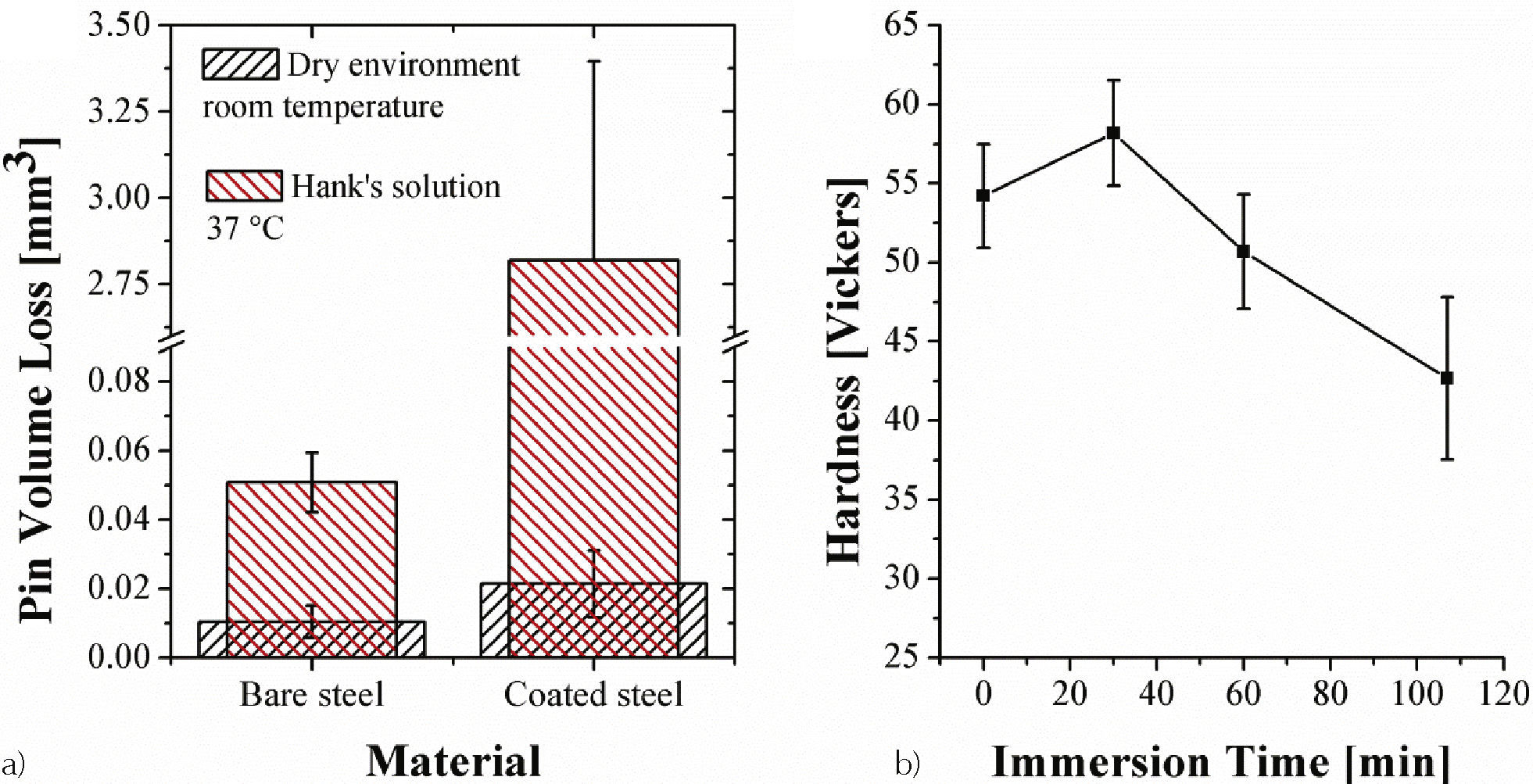

Part a) of Figure 7 shows the loss in volume of the bone spherical counterpart in both test conditions. It can be observed that in dry conditions and in Hank's solution at 37¿C, coated steel samples cause more wear in bone pin because of its greater hardness compared to bare steel. Analyzing each material is observed that wear was more severe when test was performed in Hank's solution at 37¿C than when it was in dry conditions. This can be attributed to a decrease in mechanical properties of the bone immerse in a liquid environment which simulates blood plasma, as evidenced in part b) of Figure 7, which shows that bone loses hardness if it is immersed in the fluid, and lower hardness leads to increased wear.

Conclusions- •

As depositing calcium titanate by magnetron sputtering onto AISI 304 stainless steel using a CaTiO3 as cathode obtained by powder technology, a coating was obtained consisting of Pbnm orthorrombic calcium titanate, Pm–3m cubic calcium titanate, titanium oxide (anatase) and calcium oxide. The thickness of the coating was about 750 nm, with a hardness of 6.3 ± 0.1 and an elastic modulus of 133.69 ± 10.

- •

When in contact, polished steel AISI 304 with spherical bovine bone in pin-on-disc tested with a load of 3 N, the wear mechanisms that occur are pin volume loss, bone adhesion to the steel and steel abrasion. Under the same conditions but with calcium titanate coated steel as a flat counter-part, wear bone also occurs and bone adhesion to the disc without abrasion or detachment of the coating. The friction coefficient in each case was 0.77 ± 0.11 and 0.84 ± 0.13.

- •

In Hank's solution, when in contact with both AISI 304 and calcium titanate coated, AISI 304 with spherical bovine bone in pin-on-disc tested with a load of 3 N, the wear mechanisms that occur are pin volume loss and bone adhesion to the disks. Friction coefficients were 0.89 ± 0.12 and 0.65 ± 0.12.

- •

It can be observed that in case of mutual movement between bone and steel in biological medium, the bone damage is more severe if steel is coated with calcium titanate. Because of that it is important to measure the adherence of the coating to the bone, in order to analyze its viability as a coating in hip stems.

Citation for this article:

Chicago style citation

Esguerra-Arce, Johanna, Yesid Aguilar-Castro, William Aperador-Chaparro, Leonid Ipaz-Cuastumal, Gilberto Bolaños-Pantoja, Carlos Alberto Rincón-López. Tribological Behavior of Bone Against Calcium Titanate Coating in Simulated Body Fluid. Ingeniería Investigación y Tecnología, XVI, 02 (2015): 279-286.

ISO 690 citation style:

Esguerra-Arce J., Aguilar-Castro Y., Aperador-Chaparro W., Ipaz-Cuastumal L., Bolaños-Pantoja G.B., Rincón-López C.A. Tribological Behavior of Bone Against Calcium Titanate Coating in Simulated Body Fluid. Ingeniería Investigación y Tecnología, volume XVI (issue 2), April-June 2015: 279-286.

About the authors

Johanna Esguerra-Arce. She obtained his bachelor's degree in Materials Engineering at The Universidad del Valle, Colombia, and is a Ph.D. candidate in Engineering Doctorate with major in Materials Engineering. Her work has been presented in various national and international forums and is aimed at biomaterials and coatings obtained by physical vapor deposition methods. She has been occasional professor in Department of Material Engineering at The Universidad del Valle.

Yesid Aguilar-Castro. He holds a master's in Metallurgy and Materials Science and a Ph. D in Materials and its New Technologies from Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. He has more than twelve years of professional experience as a professor at the Universidad del Valle and is appointed as a full time professor at the school of Materials Engineering. He has dedicated his work to tribology and supervises thesis work at the bachelor, master and doctoral levels.

William Aperador-Chaparro. Research Professor of Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, PhD in Materials Engineering from the Universidad del Valle. He obtained the degree of Master of Metallurgy and Materials Science from Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC-Tunja), he also has a degree in physicist from the same university. He is a researcher of the Volta group in Mechatronics Engineering program.

Leonid Ipaz-Cuastumal. Professor at Universidad Autónoma de Occidente. PhD in Materials Engineering from the Universidad del Valle, also has a degree in Materials Engineer from the same university. His main research interests are synthesis and characterization of hard coatings. He is a researcher of the Thin Films Group in the Physics Department of The Universidad del Valle.

Gilberto Bolanos-Pantoja. He obtained his bachelor's degree in physics at the Universidad del Valle, Master and Doctoral studies of science (physics) at the same university. He is a research professor at The Universidad del Cauca. The research is aimed at manufacturing of multilayer hard coatings and phase transitions. He has directed 14 B.Ing. theses, and co-directed 2 doctoral theses.

Carlos Alberto Rincón-López. His doctoral degree is from The Universidad del Valle (science-physics) and holds a master in physics from Universidad Simón Bolívar. At present he is an associate professor at The Universidad del Cauca. His research work has centered on plasma physics and coatings obtained by physical vapor deposition. He has directed various B.Ing. theses and has participate as a referee in 10 master and doctoral theses.