This paper presents results of research aimed at supporting information user learning in an undergraduate psychology program of a Colombian university, where the following methodological steps were followed: 1) From the perspective of a semiotic framework, information-literacy competencies were reconceived, and after a period of observation, re-typified. 2) Research on information-literacy competencies was contrasted with challenges, needs and problems in the context of undergraduate education. 3) A proposal is forwarded that addresses information literacy, research and academic-writing competencies needed by first-year undergrads. Results show the importance of coordinating roles and processes that are mindful of specific educational contexts and disciplines. These factors are especially significant in promoting information user learning and the wealth of synergies that arise from the attainment of competencies of diverse orders.

Se presentan los resultados de una investigación cuyo objetivo principal es el apoyo al aprendizaje de usuarios de información en educación profesional universitaria. La estrategia metodológica, que tiene como contexto un programa profesional de psicología en una universidad colombiana, se estructuró y desarrolló en tres fases consecutivas: i) reconceptualización, observación y caracterización de competencias informacionales desde la perspectiva semiótica del discurso; ii) confrontación con retos, necesidades y problemas que plantea la investigación a la educación profesional universitaria y iii) propuesta de apoyo a la formación de estudiantes de primer semestre desde el marco del desarrollo de competencias investigativas, informacionales y lecto-escriturales. Se concluye denotando la importancia y los logros obtenidos cuando se armonizan los diferentes roles y procesos que apoyan el aprendizaje de los usuarios de información, en particular cuando se tienen en cuenta las dimensiones contextuales, disciplinares y educativas y, en especial, la sinergia ante el desarrollo de competencias de diferente orden.

The nature of Informational Competency (IC) is quite complex because of the many meanings such a concept can convey in addition to the many associated variables and the scant conceptual support that, such as they are, are not measurement-based definitions. Moreover, epistemological and theoretical efforts to understand information users are rooted in historical and cultural assumptions informing the nature of the person-to-information relationship; and these constructs consequently tend to diverge rather than converge on any one definition of Informational Competency (Marciales Vivas et al., 2010).

This complexity is largely responsible for the scant availability of measures of the nature of IC. A description of the features comprising IC, with a comprehensive and coherent articulation of associated variables, would constitute a valuable contribution to this field of problems (Marciales Vivas et al., 2010). An examination of the results of research on IC with regard to university education provides a useful starting point for drawing out a definition of IC. This research centers on an intervention performed in the Psychology program of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (PUJ)1 carried out by the Learning and Information Society research group,2 which performed an IC description study with first year students. This study also provided material for an educational proposal favoring the development of research reading and writing competencies, which in view of its scope is a shared duty of information science professionals, professors and faculty.

Correspondingly, this paper documents the several phase of the research experience in six sections, each of which addresses one of the following matters: 1) The intervention context and the research design; 2) The reconceptualization experience; 3) Description of the typification experience; 4) The challenges posed by the research with regard to the training of student information users; 5) Support for information users, and 6) Final discussion and reflection.

INTERVENTION CONTEXT AND RESEARCH DESIGN: THE ACADEMIC PROGRAM AND THE AIMS OF THE RESEARCH PROJECTPsychology is a lecture-based undergraduate program ascribed in the Faculty of Psychology of PUJ. The program is targeted to students interested in: i) understanding the purview of Psychology; ii) understanding and assuming commitment to resolve the country's social problems; iii) acquiring social competencies in order to establish relationships and work in teams; iv) assuming responsibility and taking on academic commitments; v) development of reflective capacity and flexibility needed to deal with personal life situations.3

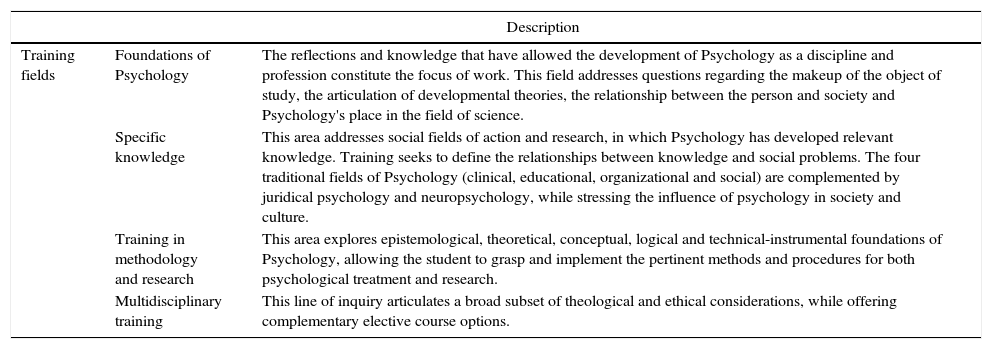

The Psychology curriculum is structured on the basis of two conceptual elements: 1) the fields of training and 2) the areas of problems with their respective transversal dimensions. Regarding fields of training, the formative proposal exploits this perspective to refer to and understand the discipline and profession as a structured space of knowledge and disciplinary development. Table 1 describes the four fields of training included in the programs.

Training fields in the Psychology program of PUJ.

| Description | ||

|---|---|---|

| Training fields | Foundations of Psychology | The reflections and knowledge that have allowed the development of Psychology as a discipline and profession constitute the focus of work. This field addresses questions regarding the makeup of the object of study, the articulation of developmental theories, the relationship between the person and society and Psychology's place in the field of science. |

| Specific knowledge | This area addresses social fields of action and research, in which Psychology has developed relevant knowledge. Training seeks to define the relationships between knowledge and social problems. The four traditional fields of Psychology (clinical, educational, organizational and social) are complemented by juridical psychology and neuropsychology, while stressing the influence of psychology in society and culture. | |

| Training in methodology and research | This area explores epistemological, theoretical, conceptual, logical and technical-instrumental foundations of Psychology, allowing the student to grasp and implement the pertinent methods and procedures for both psychological treatment and research. | |

| Multidisciplinary training | This line of inquiry articulates a broad subset of theological and ethical considerations, while offering complementary elective course options. | |

Source: Drawn from the program website.

The educational agents understand the inquiry areas are guiding enunciations of the problems that are relevant to psychology, around which questions can be posed and debate structured. These guiding axes also serve to orient research production and undergraduate education standards. As such, these inquiry areas are divided into four salient aspects: the historical, epistemological, methodological and theoretical.

As demonstrated by the profile of the graduate and the conceptual elements of the educational proposal, this should be strengthened in accord with the tendencies and demands of the specific field of training. This challenge must be understood and faced from the standpoint of research and intervention integrating the diverse educational agents who participate in the delivery of the program. One intuits that the conceptual elements of the program and the educational components demand educational challenges that go beyond the discipline, and in this regard development of IC is key. This commitment requires a typification and/or definition of informational competencies, as well as a visualization of educational proposals favoring the development of transversal competencies.

As influential agents in the programs, the members of the research group drafted a research project whose objective is to provide answers to questions about the typification of students as information users and thereby support the creation and execution of formative proposals. To this end, in terms of methodology, the research proposal was structured in four specific experiential phases:

- •

Phase I: Referential framework. This consists of the experience aimed at determining the conceptual and theoretical support for the IC definition study.

- •

Phase II: Characterization. The experience of construction of an instrument for observing IC and its respective typification process. This phase was comprised of two specific research designs, which shall be described farther on.

- •

Phase III: Complementation. The experience of determining the relevant challenges, needs and problems issuing from research associated with the object and context of the study.

- •

Phase IV: Intervention proposal. The experience of applying the research results.

Published theory and research on IC stress the traditional ideas of the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL, 2000) and the American Library Association (ALA, 1989), which understands IC as one's ability to know when information is required, combined with the skills to locate it, understand its organization, assess its value, learn from it and put it to use effectively (Marciales Vivas et al., 2010; Barbosa-Chacón et al., 2010).

These works focus on the acquisition, development and demonstration of individual abilities; and the identification of information search, assessment and use practices (Marciales Vivas et al., 2010). There is quite a bit of discrepancy between these traditional conceptions and the reconceptualization proposed herein, which underpins the typification of IC profiles.

The proposed reconceptualization begins by affording value to the history of the concept of information science, which is comprised of three foundational vectors: i) the preference for measuring knowledge through objective tests; ii) the focus on information processing, and iii) the interest in accounting for the cultural context of the users. This progression occurred largely under the influence of Vygotsky in the decade of the 1990s (Montiel-Overall, 2007).

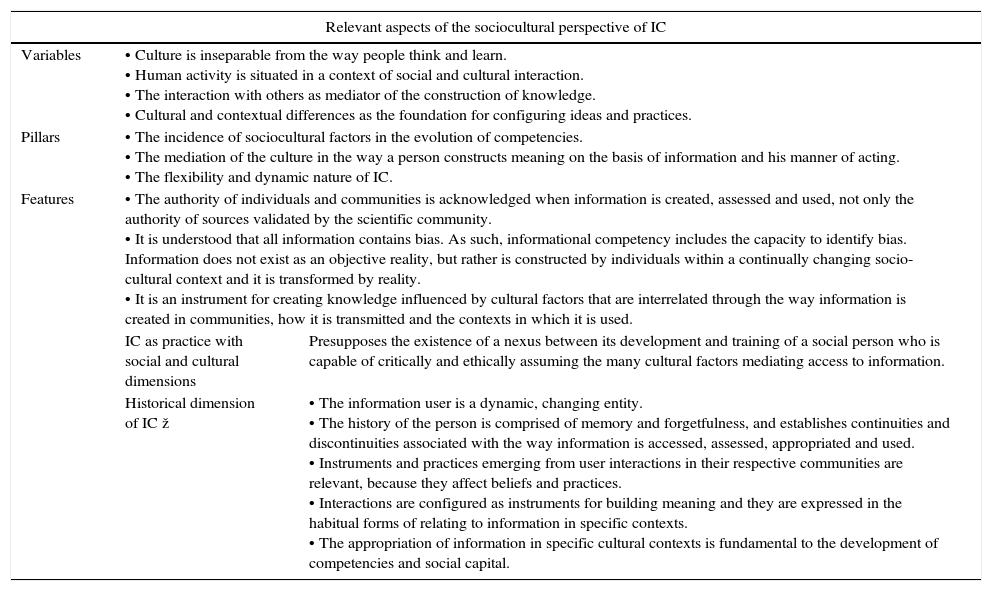

The reconceptualization proposed rightly belongs to the last stage in this progression, whose salient features are shown in Table 2.

Sociocultural Perspective of IC.

| Relevant aspects of the sociocultural perspective of IC | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | • Culture is inseparable from the way people think and learn. • Human activity is situated in a context of social and cultural interaction. • The interaction with others as mediator of the construction of knowledge. • Cultural and contextual differences as the foundation for configuring ideas and practices. | |

| Pillars | • The incidence of sociocultural factors in the evolution of competencies. • The mediation of the culture in the way a person constructs meaning on the basis of information and his manner of acting. • The flexibility and dynamic nature of IC. | |

| Features | • The authority of individuals and communities is acknowledged when information is created, assessed and used, not only the authority of sources validated by the scientific community. • It is understood that all information contains bias. As such, informational competency includes the capacity to identify bias. Information does not exist as an objective reality, but rather is constructed by individuals within a continually changing socio-cultural context and it is transformed by reality. • It is an instrument for creating knowledge influenced by cultural factors that are interrelated through the way information is created in communities, how it is transmitted and the contexts in which it is used. | |

| IC as practice with social and cultural dimensions | Presupposes the existence of a nexus between its development and training of a social person who is capable of critically and ethically assuming the many cultural factors mediating access to information. | |

| Historical dimension of IC ž | • The information user is a dynamic, changing entity. • The history of the person is comprised of memory and forgetfulness, and establishes continuities and discontinuities associated with the way information is accessed, assessed, appropriated and used. • Instruments and practices emerging from user interactions in their respective communities are relevant, because they affect beliefs and practices. • Interactions are configured as instruments for building meaning and they are expressed in the habitual forms of relating to information in specific contexts. • The appropriation of information in specific cultural contexts is fundamental to the development of competencies and social capital. | |

Source: Adapted from Marciales Vivas et al. (2010: 646-648) and Barbosa-Chacón et al. (2010, 2012: 128-131)

On the basis of these ideas, we propose a definition of IC that diverges somewhat from the traditional definition while not altogether abandoning it: Information competency is the web of adhesions, beliefs and relationships existing between motivation and aptitudes of the knowledge seeking person, built up over a long history of formal and informal learning contexts. This web of relationships acts as a referential matrix of the manners of appropriation of information, which occurs as a result of accessing, assessing and using information and express the cultural contexts in which they were constructed. (Barbosa-Chacón et al., 2010: 137. Translated from Spanish)

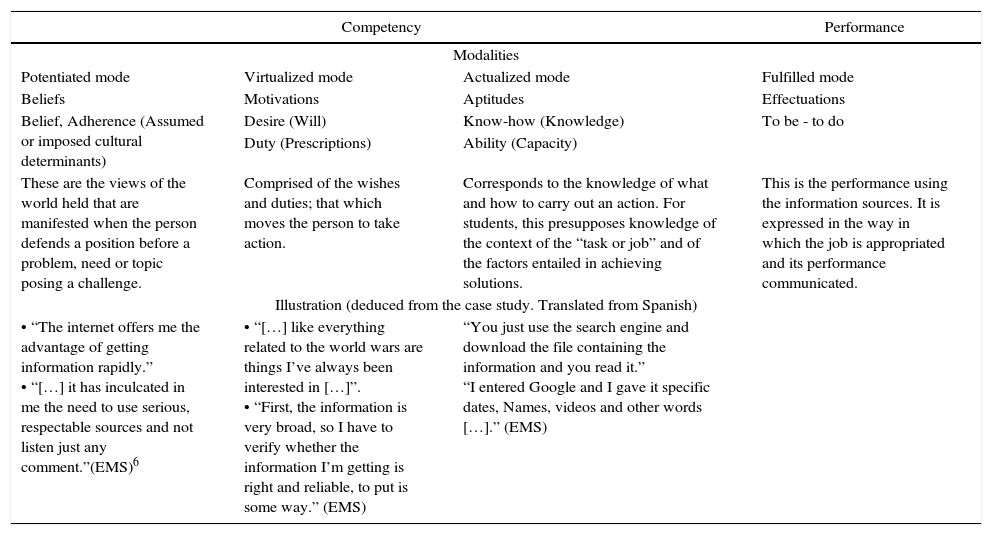

Defined in this way, IC becomes a construct in which interrelated conditions and assumptions articulate the four modalities of Potentiating, Virtualizing, Actualizing and Fulfillment (Greimas, 1989; Serrano Orejuela, 2003; Alvarado, 2007; Rosales, 2008). According to Greimas: i) the competence is configured as the being of doing, a potential state in which the act is a hypotactic structure that fuses competence and performance, and ii) the know-how corresponds only to one of the modalities constituted by the competence, understood as know-how that precedes performance. Consequently, the competence consists of the pre-existing conditions that make performance possible. Performance is in itself nothing other than the form the action takes and should not be conflated with the competence properly speaking (Alvarado, 2007).

With regard to the information supplied, the actions of person using an information source are mediated by diverse conditions he or she brings to the fore, including know-how (cognitive competence); ability (capacity); desire (will); and duty (prescription). This means when the person is modalized by his beliefs, he has assumed the determinants of both his culture and social group (Alvarado, 2007).

The levels or modes of existence are shown in Table 3,4 which also includes data form the case study5 (See development criteria in Table 4). These levels or modes of existence account for the elements that comprise and articulate the reconceptualization of IC, while also framing the typification of the information user profile. A broad examination of theoretical and procedural aspects supporting the reconceptualization performed can be found in Marciales Vivas et al. (2008) and Barbosa-Chacón et al. (2010, 2011).

Modes of existence of the competency.

| Competency | Performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Modalities | |||

| Potentiated mode | Virtualized mode | Actualized mode | Fulfilled mode |

| Beliefs | Motivations | Aptitudes | Effectuations |

| Belief, Adherence (Assumed or imposed cultural determinants) | Desire (Will) | Know-how (Knowledge) | To be - to do |

| Duty (Prescriptions) | Ability (Capacity) | ||

| These are the views of the world held that are manifested when the person defends a position before a problem, need or topic posing a challenge. | Comprised of the wishes and duties; that which moves the person to take action. | Corresponds to the knowledge of what and how to carry out an action. For students, this presupposes knowledge of the context of the “task or job” and of the factors entailed in achieving solutions. | This is the performance using the information sources. It is expressed in the way in which the job is appropriated and its performance communicated. |

| Illustration (deduced from the case study. Translated from Spanish) | |||

| • “The internet offers me the advantage of getting information rapidly.” • “[…] it has inculcated in me the need to use serious, respectable sources and not listen just any comment.”(EMS)6 | • “[…] like everything related to the world wars are things I’ve always been interested in […]”. • “First, the information is very broad, so I have to verify whether the information I’m getting is right and reliable, to put is some way.” (EMS) | “You just use the search engine and download the file containing the information and you read it.” “I entered Google and I gave it specific dates, Names, videos and other words […].” (EMS) | |

Source: Based on Alvarado (2007: 5-9) and adapted from Barbosa-Chacón et al. (2010: 132-136)

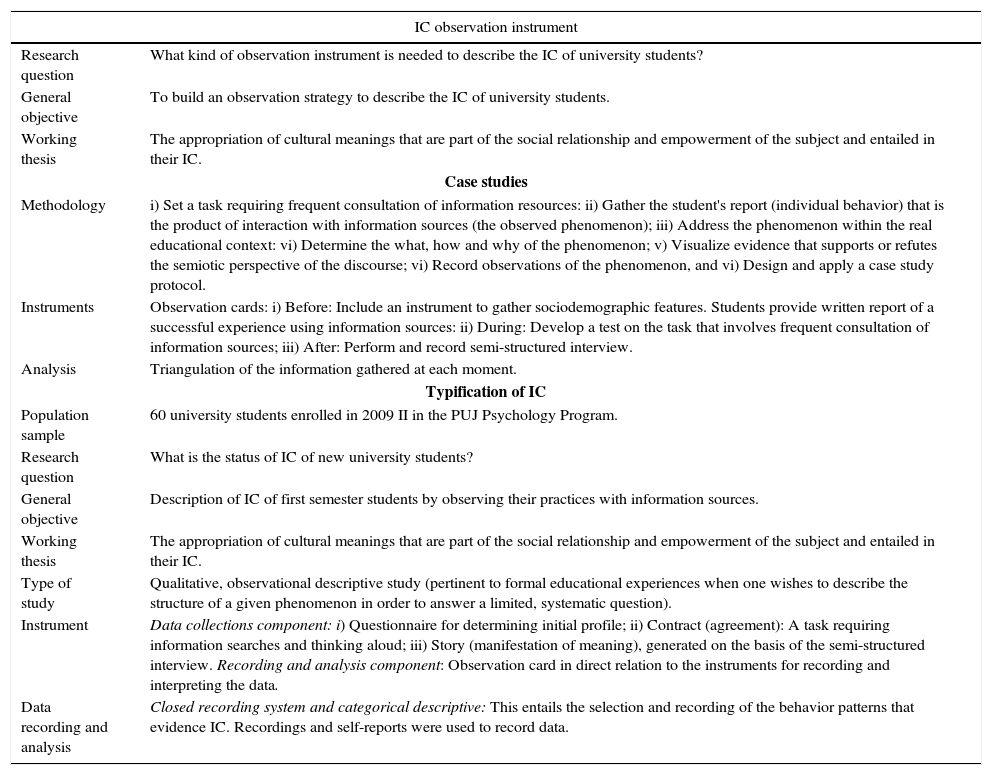

Research design for typification of informational competency.

| IC observation instrument | |

|---|---|

| Research question | What kind of observation instrument is needed to describe the IC of university students? |

| General objective | To build an observation strategy to describe the IC of university students. |

| Working thesis | The appropriation of cultural meanings that are part of the social relationship and empowerment of the subject and entailed in their IC. |

| Case studies | |

| Methodology | i) Set a task requiring frequent consultation of information resources: ii) Gather the student's report (individual behavior) that is the product of interaction with information sources (the observed phenomenon); iii) Address the phenomenon within the real educational context: vi) Determine the what, how and why of the phenomenon; v) Visualize evidence that supports or refutes the semiotic perspective of the discourse; vi) Record observations of the phenomenon, and vi) Design and apply a case study protocol. |

| Instruments | Observation cards: i) Before: Include an instrument to gather sociodemographic features. Students provide written report of a successful experience using information sources: ii) During: Develop a test on the task that involves frequent consultation of information sources; iii) After: Perform and record semi-structured interview. |

| Analysis | Triangulation of the information gathered at each moment. |

| Typification of IC | |

| Population sample | 60 university students enrolled in 2009 II in the PUJ Psychology Program. |

| Research question | What is the status of IC of new university students? |

| General objective | Description of IC of first semester students by observing their practices with information sources. |

| Working thesis | The appropriation of cultural meanings that are part of the social relationship and empowerment of the subject and entailed in their IC. |

| Type of study | Qualitative, observational descriptive study (pertinent to formal educational experiences when one wishes to describe the structure of a given phenomenon in order to answer a limited, systematic question). |

| Instrument | Data collections component: i) Questionnaire for determining initial profile; ii) Contract (agreement): A task requiring information searches and thinking aloud; iii) Story (manifestation of meaning), generated on the basis of the semi-structured interview. Recording and analysis component: Observation card in direct relation to the instruments for recording and interpreting the data. |

| Data recording and analysis | Closed recording system and categorical descriptive: This entails the selection and recording of the behavior patterns that evidence IC. Recordings and self-reports were used to record data. |

Source: Based on Barbosa-Chacón et al. (2011: 8-14, 2012: 6-8)

With the result of the reconceptualization of IC, the construction of an instrument for IC pre-typification observation was undertaken in accord with specific research designs that are described in Table 4. Broader theoretical and procedural support for these studies can be reviewed in Castañeda-Peña et al. (2010), Barbosa-Chacón et al. (2012) and González Niño et al. (2013).

In order to establish the information search task for this process, a review of similar experiences was performed which identified a task used by Hofer (2004) in the study of personal epistemologies. In the task proposed by Hofer, the criteria of Documentation and Validation and Potential Interest (Marciales Vivas et al., 2010) are met.

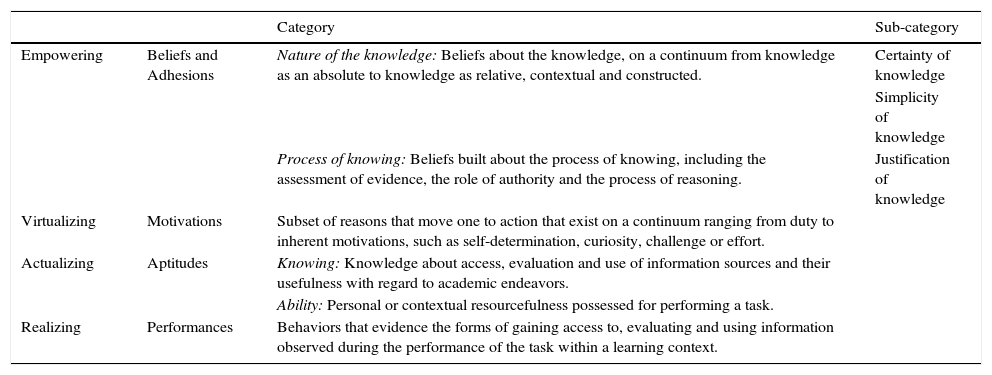

The analysis processThe understanding of modalities of competency led to the identification of categories and subcategories for observation of IC. Table 5 provides the definitions of each of these in accord with the diverse modalities (González Niño et al., 2013; Barbosa-Chacón et al., 2012).

Structural categories and sub-categories.

| Category | Sub-category | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Empowering | Beliefs and Adhesions | Nature of the knowledge: Beliefs about the knowledge, on a continuum from knowledge as an absolute to knowledge as relative, contextual and constructed. | Certainty of knowledge |

| Simplicity of knowledge | |||

| Process of knowing: Beliefs built about the process of knowing, including the assessment of evidence, the role of authority and the process of reasoning. | Justification of knowledge | ||

| Virtualizing | Motivations | Subset of reasons that move one to action that exist on a continuum ranging from duty to inherent motivations, such as self-determination, curiosity, challenge or effort. | |

| Actualizing | Aptitudes | Knowing: Knowledge about access, evaluation and use of information sources and their usefulness with regard to academic endeavors. | |

| Ability: Personal or contextual resourcefulness possessed for performing a task. | |||

| Realizing | Performances | Behaviors that evidence the forms of gaining access to, evaluating and using information observed during the performance of the task within a learning context. |

Source: Based on Barbosa-Chacón et al. (2012: 6-8) and González Niño et al. (2013: 116-118)

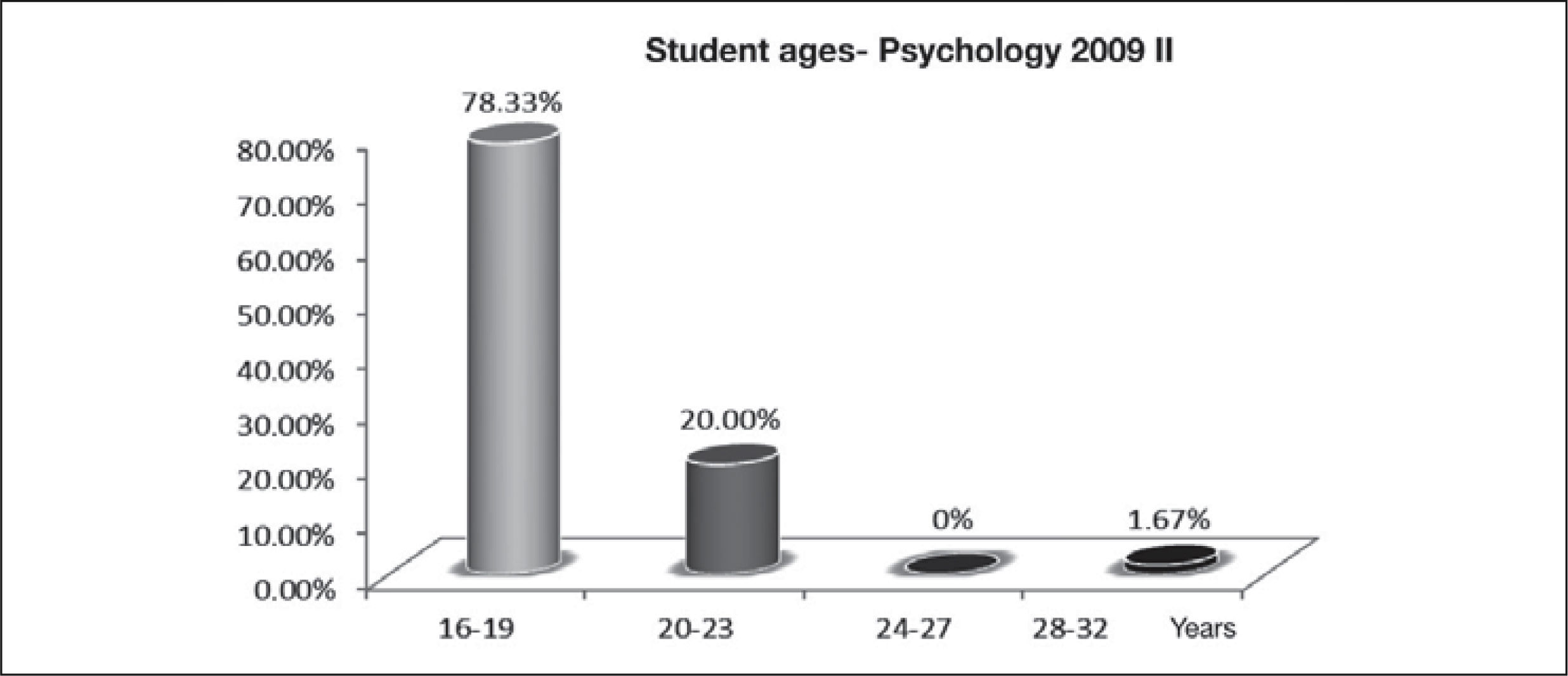

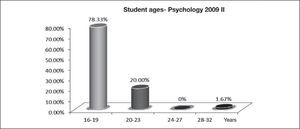

Sixty students of the Psychology Program participated in the study. The average age of the subject was 18.65 years and the age distribution is shown in Chart 1, which shows that a large majority (78.33%) were not yet 19 years-old.

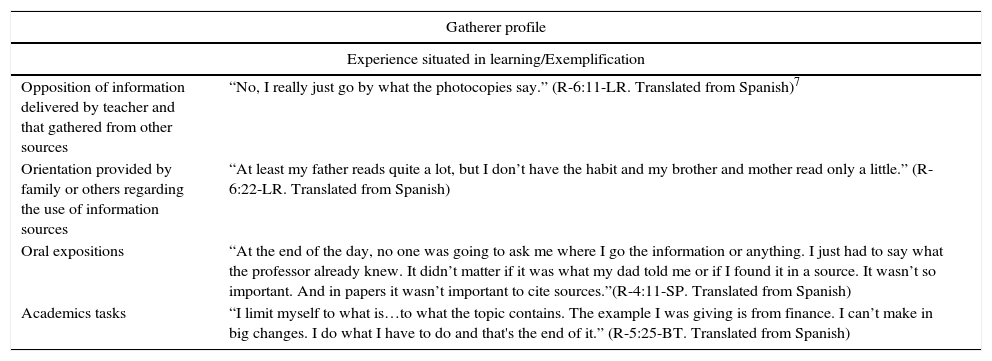

Typification of the gatherer profile.

| Gatherer profile | |

|---|---|

| Experience situated in learning/Exemplification | |

| Opposition of information delivered by teacher and that gathered from other sources | “No, I really just go by what the photocopies say.” (R-6:11-LR. Translated from Spanish)7 |

| Orientation provided by family or others regarding the use of information sources | “At least my father reads quite a lot, but I don’t have the habit and my brother and mother read only a little.” (R-6:22-LR. Translated from Spanish) |

| Oral expositions | “At the end of the day, no one was going to ask me where I go the information or anything. I just had to say what the professor already knew. It didn’t matter if it was what my dad told me or if I found it in a source. It wasn’t so important. And in papers it wasn’t important to cite sources.”(R-4:11-SP. Translated from Spanish) |

| Academics tasks | “I limit myself to what is…to what the topic contains. The example I was giving is from finance. I can’t make in big changes. I do what I have to do and that's the end of it.” (R-5:25-BT. Translated from Spanish) |

| Corresponding features |

|---|

| • Beliefs about the existence of truth in a given external source of information. |

| • Internet is valued as a useful tool because: “everything can be found there.” |

| • Gathering a lot of information and possessing it are two important criteria. |

| • There are few familial or scholastic guiding experiences regarding the use of information sources. |

| • Learning about access, evaluation and use of information sources comes largely from trial and error. |

| • Successful academic results receiving positive grades prevail over time. |

| • The motivation for doing academic work entailing access, evaluation and use of sources is largely a function of duty or obligation. |

Source: Adapted from Castañeda-Peña et al. (2010: 205) and Marciales Vivas et al. (2010: 14-17)

The age distribution is important in terms of how it affects informational behavior, especially with regard to habitual or preferred practices of using information sources characteristic of an age group. In this regard, the term “practice” as used herein refers to doing something in a historical and cultural context providing it meaning, revealing the site-specific character of the competence in the history of the subject (Wenger, McDermott, and Snyder, 2002). The conceptual and methodological referents presented previously configure the framework of the definition of three IC profiles for students. These profiles shall be addressed later in this paper.

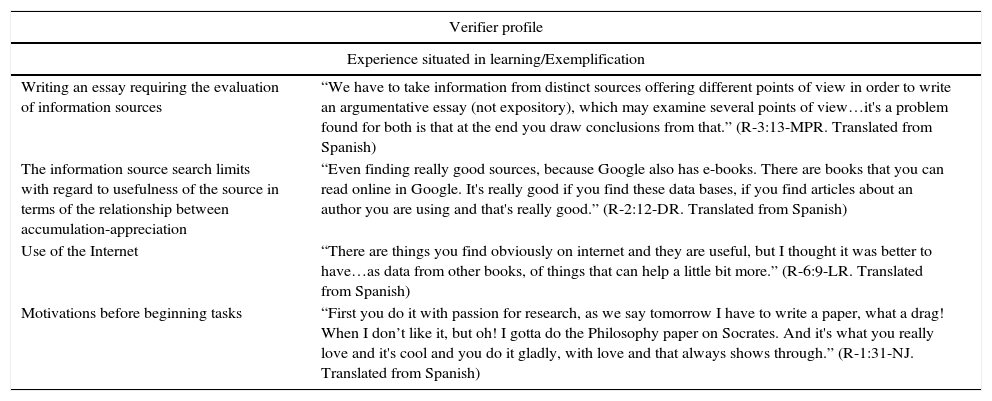

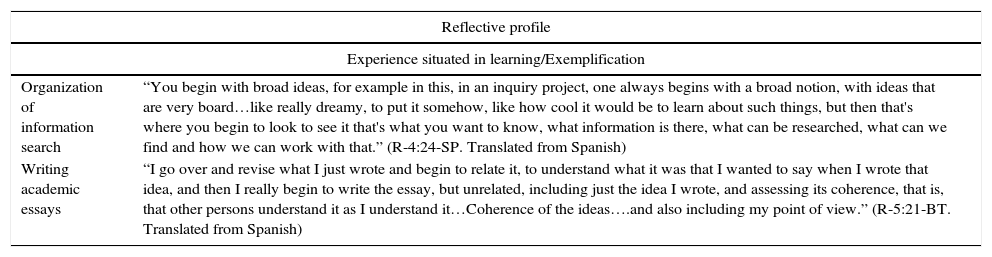

Informational competency profiles as products of typificationEach profile was delimited as a function of the competency profile, in the understanding that the profile is not a static construct. Thus, the potential beliefs, motivations and abilities for each profile, which manifest in the ways a person accesses, assesses and uses information, were identified. The following tables show the outstanding features of each profile, while accounting for situated learning experiences, and provide exerts from some of the student reports gathered during the study.

Typification of the information verifier profile.

| Verifier profile | |

|---|---|

| Experience situated in learning/Exemplification | |

| Writing an essay requiring the evaluation of information sources | “We have to take information from distinct sources offering different points of view in order to write an argumentative essay (not expository), which may examine several points of view…it's a problem found for both is that at the end you draw conclusions from that.” (R-3:13-MPR. Translated from Spanish) |

| The information source search limits with regard to usefulness of the source in terms of the relationship between accumulation-appreciation | “Even finding really good sources, because Google also has e-books. There are books that you can read online in Google. It's really good if you find these data bases, if you find articles about an author you are using and that's really good.” (R-2:12-DR. Translated from Spanish) |

| Use of the Internet | “There are things you find obviously on internet and they are useful, but I thought it was better to have…as data from other books, of things that can help a little bit more.” (R-6:9-LR. Translated from Spanish) |

| Motivations before beginning tasks | “First you do it with passion for research, as we say tomorrow I have to write a paper, what a drag! When I don’t like it, but oh! I gotta do the Philosophy paper on Socrates. And it's what you really love and it's cool and you do it gladly, with love and that always shows through.” (R-1:31-NJ. Translated from Spanish) |

| Corresponding features |

|---|

| • The belief that knowledge is relative, contextual and obeys the perspective from which it is approached. |

| • The search for information sources is performed largely through data bases, libraries and web texts on research, sources that are verified by putting them in juxtaposition with others. |

| • The use of search engines, generally Google, obeys two motives: i) time limitation and ii) their usefulness in creating a general framework for the research topic. |

| • The possibility of learning something new is a key motivation to use sources. |

Source: Adapted from Castañeda-Peña et al. (2010: 205) and Marciales Vivas et al. (2010: 17-19)

It is clear that both motivation and life experience involved in IC of the gatherer subject differ considerably in the verifier profile.

The protagonist role of the subject in the reflective profile, especially in the rationale provided for the informational behavior as related to learning, is particularly apparent.

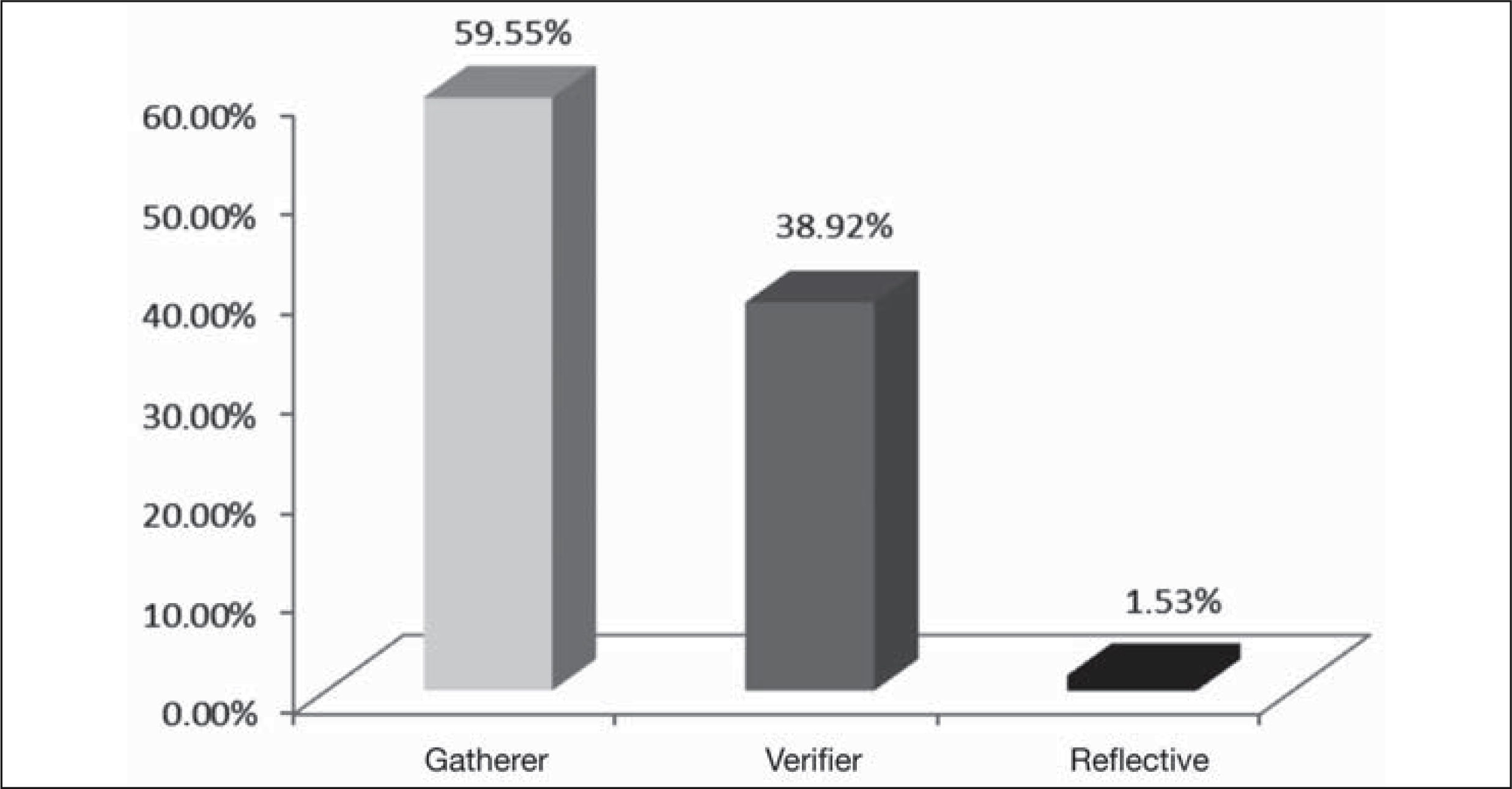

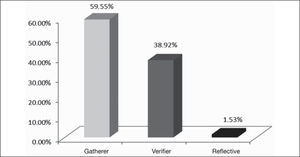

After determining the three profiles, it was found that the gatherer profile is the most representative of students entering the university, while the reflective profile is the scarcest. In fact, only one student was classified as a reflective type, which in accord with the description already given is the most important and valuable IC profile. The distribution of profiles is shown in Chart 2.

Typification of the reflective profile.

| Reflective profile | |

|---|---|

| Experience situated in learning/Exemplification | |

| Organization of information search | “You begin with broad ideas, for example in this, in an inquiry project, one always begins with a broad notion, with ideas that are very board…like really dreamy, to put it somehow, like how cool it would be to learn about such things, but then that's where you begin to look to see it that's what you want to know, what information is there, what can be researched, what can we find and how we can work with that.” (R-4:24-SP. Translated from Spanish) |

| Writing academic essays | “I go over and revise what I just wrote and begin to relate it, to understand what it was that I wanted to say when I wrote that idea, and then I really begin to write the essay, but unrelated, including just the idea I wrote, and assessing its coherence, that is, that other persons understand it as I understand it…Coherence of the ideas….and also including my point of view.” (R-5:21-BT. Translated from Spanish) |

| Corresponding features |

|---|

| • Tendency to formulate one's own questions before beginning search of information sources. |

| • Planning before undertaking search. |

| • The practices suggest the student assumes the role of active builders of information. Their educational activity is underpinned in both their interests and their ability to be critical of information sources regardless of their authority. |

| • What is important, beyond the academic tasks themselves, is how these contribute to the life projects and the value to be found in new knowledge. |

Source: Adapted from Castañeda-Peña et al. (2010: 205) and Marciales Vivas et al. (2010: 20-22)

In view of this reality, questions and educational commitments with regard to all fields of area of training arise, but especially with regard to information science. For this reason, we shall stress some challenges derived from the research and which constitute the foundation for proposing interventions in the university context.

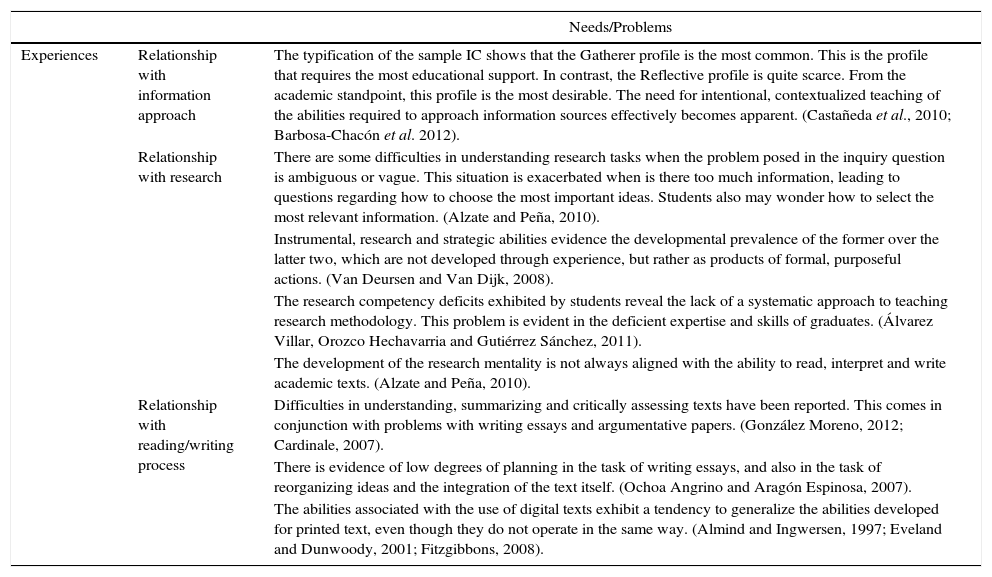

CHALLENGES POSED BY RESEARCH REGARDING THE TRAINING OF UNIVERSITY STUDENT INFORMATION USERS. COMMITMENTS FOR QUALIFYING NEW STUDENTSThe contributions to and challenges posed by IC research are multidimensional. The development IC demands close collaboration among the diverse parties responsible for training processes. In this regard, one would do well to ask about the complementary functions that information science professionals must assume to support students in the information society, where informational competency has implications in the educational, economic, social and political spheres. These implications, according to Garmendia Bonilla (2005), are part of the informational culture needed to perform in today's world. Research also serves to reveal conflicts between the information society and the process of constructing knowledge. These points of friction include: i) the rootlessness of information, which will require revaluation of the concept of authorship, something seemingly irrelevant when it is so easy simply to note the date of consultation and the web page; ii) the relationship between text and hypertext, entailing actions of hierarchy and centrality, requiring the development of competencies for lateral reading (Fainholc, 2004; Eshet-Alkalai, 2004); the construction of informational source maps that show the relationships arising from the standpoint of reader-author, i.e., configured as a prosumer (Corona Rodríguez, 2012; Giurgiu and Barsan, 2008); iii); and information overload, which requires the development of pertinent management criteria for filtering information rigorously (Valverde Berrocoso and Garrido Arroyo 2005; Vonderwell, 2003). The challenges facing young information users should not be a problem if they are assumed to be digital natives in light of their evident abilities for learning and communication (Cabra-Torres and Marciales Vivas, 2009; Prensky, 2001); but the results of research have raised doubts because of the presence of the problems or necessities shown in Table 9.

Problem and needs arising from research experience.

| Needs/Problems | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experiences | Relationship with information approach | The typification of the sample IC shows that the Gatherer profile is the most common. This is the profile that requires the most educational support. In contrast, the Reflective profile is quite scarce. From the academic standpoint, this profile is the most desirable. The need for intentional, contextualized teaching of the abilities required to approach information sources effectively becomes apparent. (Castañeda et al., 2010; Barbosa-Chacón et al. 2012). |

| Relationship with research | There are some difficulties in understanding research tasks when the problem posed in the inquiry question is ambiguous or vague. This situation is exacerbated when is there too much information, leading to questions regarding how to choose the most important ideas. Students also may wonder how to select the most relevant information. (Alzate and Peña, 2010). | |

| Instrumental, research and strategic abilities evidence the developmental prevalence of the former over the latter two, which are not developed through experience, but rather as products of formal, purposeful actions. (Van Deursen and Van Dijk, 2008). | ||

| The research competency deficits exhibited by students reveal the lack of a systematic approach to teaching research methodology. This problem is evident in the deficient expertise and skills of graduates. (Álvarez Villar, Orozco Hechavarria and Gutiérrez Sánchez, 2011). | ||

| The development of the research mentality is not always aligned with the ability to read, interpret and write academic texts. (Alzate and Peña, 2010). | ||

| Relationship with reading/writing process | Difficulties in understanding, summarizing and critically assessing texts have been reported. This comes in conjunction with problems with writing essays and argumentative papers. (González Moreno, 2012; Cardinale, 2007). | |

| There is evidence of low degrees of planning in the task of writing essays, and also in the task of reorganizing ideas and the integration of the text itself. (Ochoa Angrino and Aragón Espinosa, 2007). | ||

| The abilities associated with the use of digital texts exhibit a tendency to generalize the abilities developed for printed text, even though they do not operate in the same way. (Almind and Ingwersen, 1997; Eveland and Dunwoody, 2001; Fitzgibbons, 2008). |

Source: By author

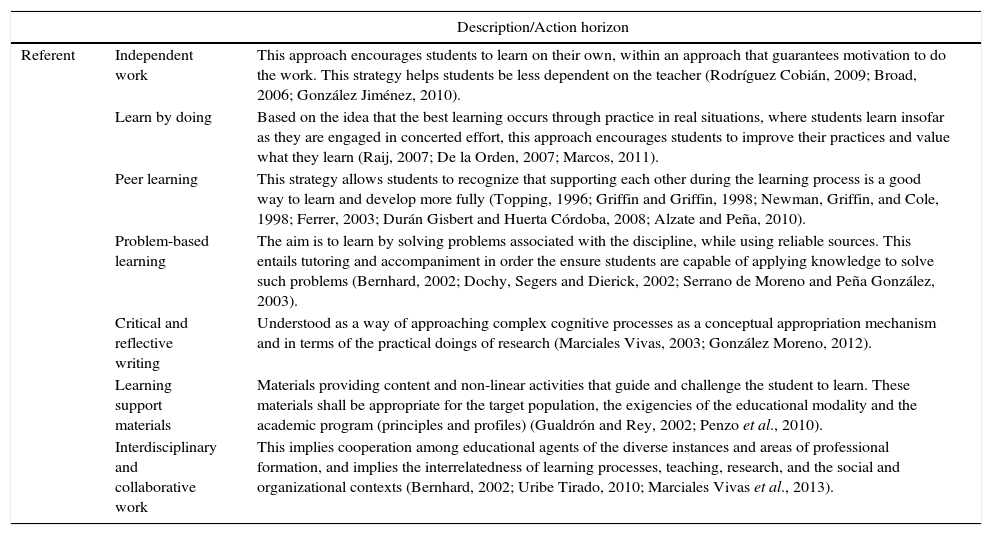

In view of these problems and needs, university educational agents must commit to IC, research skills and reading-writing abilities. This goal will demand the design of formative proposals that guarantee significant levels of appropriation, empowerment and sustainability in students; i.e., new, proper teaching approaches at the outset of academic programs will be required. (Batellino and Lissera, 2006). In this sense and as an alternative way of achieving the aforementioned levels it is important that these training programs be underpinned by theoretical and procedural benchmarks, such as those shown in Table 10.

Theoretical and procedural benchmarks underpinning training processes.

| Description/Action horizon | ||

|---|---|---|

| Referent | Independent work | This approach encourages students to learn on their own, within an approach that guarantees motivation to do the work. This strategy helps students be less dependent on the teacher (Rodríguez Cobián, 2009; Broad, 2006; González Jiménez, 2010). |

| Learn by doing | Based on the idea that the best learning occurs through practice in real situations, where students learn insofar as they are engaged in concerted effort, this approach encourages students to improve their practices and value what they learn (Raij, 2007; De la Orden, 2007; Marcos, 2011). | |

| Peer learning | This strategy allows students to recognize that supporting each other during the learning process is a good way to learn and develop more fully (Topping, 1996; Griffin and Griffin, 1998; Newman, Griffin, and Cole, 1998; Ferrer, 2003; Durán Gisbert and Huerta Córdoba, 2008; Alzate and Peña, 2010). | |

| Problem-based learning | The aim is to learn by solving problems associated with the discipline, while using reliable sources. This entails tutoring and accompaniment in order the ensure students are capable of applying knowledge to solve such problems (Bernhard, 2002; Dochy, Segers and Dierick, 2002; Serrano de Moreno and Peña González, 2003). | |

| Critical and reflective writing | Understood as a way of approaching complex cognitive processes as a conceptual appropriation mechanism and in terms of the practical doings of research (Marciales Vivas, 2003; González Moreno, 2012). | |

| Learning support materials | Materials providing content and non-linear activities that guide and challenge the student to learn. These materials shall be appropriate for the target population, the exigencies of the educational modality and the academic program (principles and profiles) (Gualdrón and Rey, 2002; Penzo et al., 2010). | |

| Interdisciplinary and collaborative work | This implies cooperation among educational agents of the diverse instances and areas of professional formation, and implies the interrelatedness of learning processes, teaching, research, and the social and organizational contexts (Bernhard, 2002; Uribe Tirado, 2010; Marciales Vivas et al., 2013). | |

Source: By author

Consequently, the next section examines a joint experience involving teachers and information science professionals, who base their initial evaluation of university students from the standpoint of the commitments associated with the information users’ learning. This effort is also informed by theoretical and procedures benchmarks set in for design and development of the aforementioned training proposals. The proposal integrates professional training and contributions from Library Science, while taking into account features of the PUJ Psychology curriculum as the context of learning.

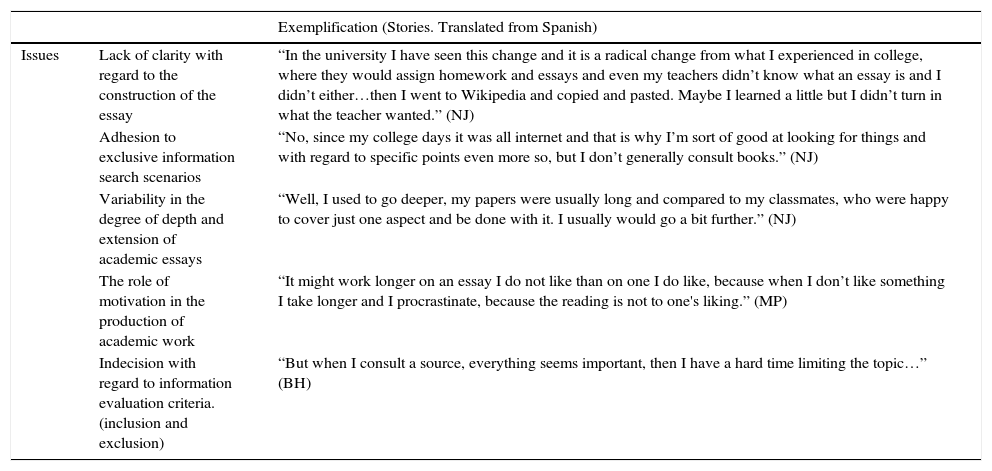

HOW TO SUPPORT LEARNING OF UNIVERSITY STUDENT INFORMATION USERS: THE APPROACH OF THE PUJ PSYCHOLOGY DEPARTMENTThe matters documented up to now evidence the stress that should be afforded to the intervention context, especially with regard to needs and problems of the target population. In accord with this idea and within the context of PUJ, the research identified specific elements of the incoming undergrad profile as a starting point for determining initial informational needs in order to plan support strategies and assess academic performance. The following table shows the problems reported by students in the first semester of 2009 II. These students participated in the typification experience described.

Problems reported in the typification study.

| Exemplification (Stories. Translated from Spanish) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Issues | Lack of clarity with regard to the construction of the essay | “In the university I have seen this change and it is a radical change from what I experienced in college, where they would assign homework and essays and even my teachers didn’t know what an essay is and I didn’t either…then I went to Wikipedia and copied and pasted. Maybe I learned a little but I didn’t turn in what the teacher wanted.” (NJ) |

| Adhesion to exclusive information search scenarios | “No, since my college days it was all internet and that is why I’m sort of good at looking for things and with regard to specific points even more so, but I don’t generally consult books.” (NJ) | |

| Variability in the degree of depth and extension of academic essays | “Well, I used to go deeper, my papers were usually long and compared to my classmates, who were happy to cover just one aspect and be done with it. I usually would go a bit further.” (NJ) | |

| The role of motivation in the production of academic work | “It might work longer on an essay I do not like than on one I do like, because when I don’t like something I take longer and I procrastinate, because the reading is not to one's liking.” (MP) | |

| Indecision with regard to information evaluation criteria. (inclusion and exclusion) | “But when I consult a source, everything seems important, then I have a hard time limiting the topic…” (BH) |

Source: By author

Situations such as these motivate educational agents of the PUJ Psychology Department to initiate several approaches for developing Informational Competencies and the research, reading and writing skills of students. One of these approaches is the pedagogical experience called the Inquiry Project (PRIN by its Spanish-languaje acronym). Typification study subjects were trained in this approach.

The Inquiry ProjectEducational agents of the Psychology Department understand that a solid appropriation of written language is a key factor for strengthening IC and another supply for financing the academic community. In addition to being fundamental for developing critical and reflective thinking, the processes of reading and writing are fundamental to learning, research and communication of ideas. In all of this, questioning plays a key role because it is the force that drives the search for knowledge (Peña, 2009).

This framework is included in the Inquiry Project, an initiative supporting incoming undergrads of the Faculty of Psychology since 2006. The purpose of this project is to inculcate students with the importance of posing questions and performing subsequent inquiry.

Through this project, the faculty expects to develop a positive attitude in students with regard to research, while creating a space for the articulation of diverse perspectives within the field of psychology. This approach promises to raise abilities to match the demands of written discourse in the field (Alzate and Peña, 2010; Marciales Vivas et al., 2010).

These objectives are materialized through a strategy that brings together several elements: i) the accompaniment of a professor; ii) pair and group work based on cooperative learning; iii) guidelines for classwork with orientation in academic genres, such as summaries, reviews and essays; and iv) synchronization of support resources (workshops and tutoring).

The didactic and pedagogical approach stands besides ongoing assessment, thanks to the participation and participation of three main educational agents: i) the professor, who acts as an “expert” and whose function is to set the general guidelines of the work; ii) the tutor, a student already trained in the project who works with the professors and serves as a link between the professor and students; and iii) the group of students, who are involved in ongoing exchange and assessment of classroom work.

The development of the Inquiry Project unfolds through the IC workshop. The following are the phases and several reflections and assessments regarding its practice.

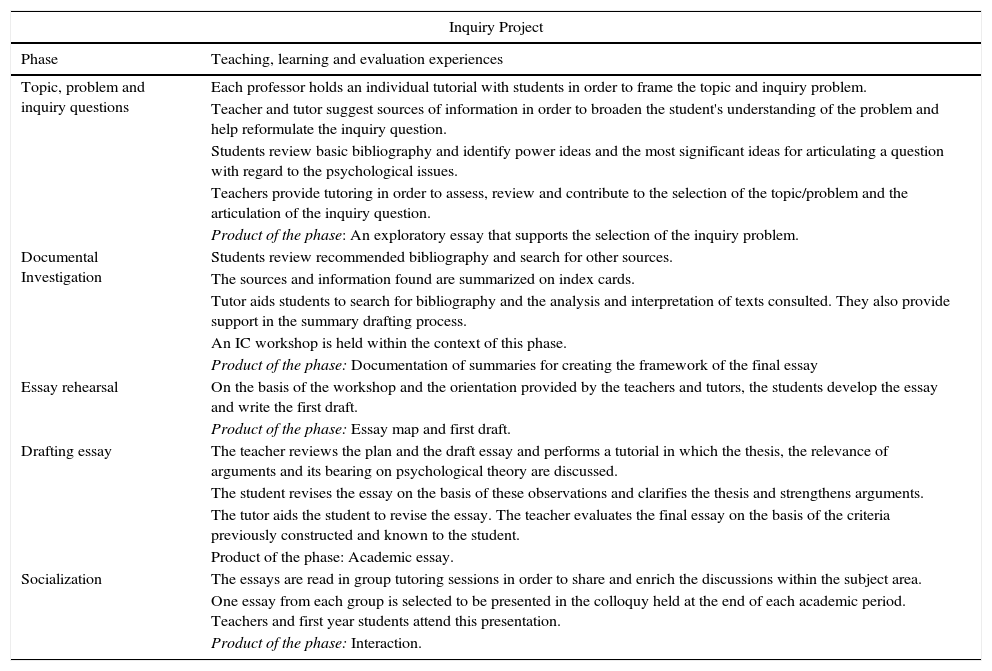

Phases of the Inquiry ProjectTable 12 provides a summary of the activities performed in each of the project phases and the description of the product to be assessed.

Phases of the Inquiry Project.

| Inquiry Project | |

|---|---|

| Phase | Teaching, learning and evaluation experiences |

| Topic, problem and inquiry questions | Each professor holds an individual tutorial with students in order to frame the topic and inquiry problem. |

| Teacher and tutor suggest sources of information in order to broaden the student's understanding of the problem and help reformulate the inquiry question. | |

| Students review basic bibliography and identify power ideas and the most significant ideas for articulating a question with regard to the psychological issues. | |

| Teachers provide tutoring in order to assess, review and contribute to the selection of the topic/problem and the articulation of the inquiry question. | |

| Product of the phase: An exploratory essay that supports the selection of the inquiry problem. | |

| Documental Investigation | Students review recommended bibliography and search for other sources. |

| The sources and information found are summarized on index cards. | |

| Tutor aids students to search for bibliography and the analysis and interpretation of texts consulted. They also provide support in the summary drafting process. | |

| An IC workshop is held within the context of this phase. | |

| Product of the phase: Documentation of summaries for creating the framework of the final essay | |

| Essay rehearsal | On the basis of the workshop and the orientation provided by the teachers and tutors, the students develop the essay and write the first draft. |

| Product of the phase: Essay map and first draft. | |

| Drafting essay | The teacher reviews the plan and the draft essay and performs a tutorial in which the thesis, the relevance of arguments and its bearing on psychological theory are discussed. |

| The student revises the essay on the basis of these observations and clarifies the thesis and strengthens arguments. | |

| The tutor aids the student to revise the essay. The teacher evaluates the final essay on the basis of the criteria previously constructed and known to the student. | |

| Product of the phase: Academic essay. | |

| Socialization | The essays are read in group tutoring sessions in order to share and enrich the discussions within the subject area. |

| One essay from each group is selected to be presented in the colloquy held at the end of each academic period. Teachers and first year students attend this presentation. | |

| Product of the phase: Interaction. | |

Source: Adapted from Marciales Vivas et al. (2010: 23-31) and Alzate and Peña (2010: 127-136)

The drafting of texts using documental sources is a common task of university students. According to Spivey and King (1989) and Vásquez (2008), this task is called “discursive synthesis,” and it entails rephrasing the original material so that is becomes a new text. As can be seen in Table 12, the Inquiry Project includes training in text drafting in its first two phases. To make these drafts, students must perform bibliographical research, condense information considerably, organize it in a new way, establish intertextual relationships, compare positions and, finally, synthesize findings in a coherent text (Alzate and Peña, 2010; Marciales Vivas et al., 2010).

As stated before, the problems inherent to writing texts often hide deficiencies in reading, understood as a social construction in which the text, reader, institution, times and places, and practice and persons play their roles. This outlook justifies the presence of ICW, which is designed to achieve two ends: on one hand it supports the development of reading and informational competencies, so students can more fully exploit the library resources at their disposal; and on the other, it serves to motivate students to read and inculcate the spirit of research and independent learning. In essence, ICW is a strategy inherent to the research process and the PUJ information user training service. The development of ICW requires teams that understand the contexts and needs of the specific projects (topics and inquiry problems) to be performed by students. This understanding provides the material for the workshop, in terms of activities and practical exercise. This allows the ICW to be meaningful and motivating. The central focus of the activities is the search for and selection of information, which entails identifying the proper mechanisms for accessing, assessing and using it critically. The concrete product of this activity is to produce a bibliography whose currency and relevance can be discussed with professors and tutors. The aim of the ICW is to position the library as an information bank, and place of study and research. (Alzate and Peña, 2010; Marciales Vivas et al., 2010).

Observation of the Inquiry Project experience- •

Regarding contents: i) early on the topics were set by the students in accord with their interests. Later on the so-called “fields of inquiry,” were established by the first-semester faculty, consisting of a menu of topics reflecting the content of their coursework; ii) to support this work, a content resource management website was launched. This website offers the opportunity to access and learn more about the project, while allowing monitoring of student work over the course of the semester. Similarly, a project Facebook page is currently being used because of popularity of social media with students.

- •

Regarding interaction. The way in which the relational moments between educational agents have been organized has allowed the promotion of stronger personal and interpersonal abilities (reasoning, staking out positions, collaboration), thereby encouraging traditional and instrumental limits associated with learning to be transcended.

- •

Regarding impact on students. Several changes were observed in the attitudes and statements of Psychology students regarding the educational experience, especially with regard to their approach to information. In this respect students: i) have begun to make better use of information, which is evident in the quantity, quality, relevance and variety of sources they consult, including the broader use of specialized journals and books; ii) have gained greater autonomy and often seen returning to the library of their own accord to carry out further research; iii) have begun to differentiate the features of academic writing and incorporate these features into their writing; iv) have reported that the Inquiry Project has allowed them to have a greater understanding of the value of information as a research resource, the responsibilities assumed when citing sources and the power it gives them to question beliefs they hold as true.

Other reflections and observations can be consulted in Alzate and Peña (2010) and Marciales Vivas et al. (2010).

FINAL REFLECTION AND DISCUSSIONInformational Competencies as a subset of beliefs, motivations and abilities built over the lifetime of a person must be understood and developed in learning contexts that provided comprehensive, variegated approaches that take into account family, schooling and other social, cultural and economic factors.

The typification provided herein establishes IC profiles, while also highlighting the needs and problems of students faced with academic challenges at the university level. As such, the profiles are posited as pre-texts for educational agents to reflect on the actions to be taken and in order to ensure that access to higher education is a genuine route to personal and social development, and that it does not become a frustration factor.

In view of the interest of educational institutions and governmental agencies in ensuring educational equality at the university level, several question are posed regarding how to make equality a condition of the educational process and not only a quantitative admissions factor. To this end, we must seek alternative coordinated and ongoing actions at earlier stages of education. This means that Library and Information Science professionals will have to re-signify their discipline, in the understanding that their work transcends technical matters. They must create mechanisms for becoming cultural agents within educational institutions. This is about broadening the nature of their professional role within the information society, while centering their efforts in three functions: information, knowledge and learning.

To achieve these transformations in the way librarians work in academic contexts will demand joint, synergistic action among professors and directors targeted at developing key competencies for life-long learning.

Universidad Industrial de Santander-Bucaramanga, Colombia.

This paper reports the results of the Learning and Information Society research group, comprised of professors from the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (PUJ), the Universidad Industrial de Santander (UIS) and the Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. Associated projects: PRE00439014390, PS4663-Vicerrectoría Académica PUJ; CH20092, CH 2012-2-Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Extensión UIS. We acknowledge the contributions of Professors Luis Bernardo Peña and Gustavo La Rotta Amaya, who are agents in the development of the Inquiry Project (PRIN) of PUJ.

Pontificia Universidad Javeriana-Bogotá, Colombia.

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas-Bogotá, Colombia.

See information in PUJ at: http://puj-portal.javeriana.edu.co/portal/page/portal/PORTAL_VERSION_2009_2010/es_inicio

See participants and research experience of the group in the following link: http://201.234.78.173:8080/gruplac/jsp/visualiza/visualizagr.jsp?nro=00000000001836

Expanded details of the program at: http://puj-portal.javeriana.edu.co/portal/page/portal/Facultad%20de%20Psicologia/INICIO

(EMS) This represents the anonymous identity of the participating student in the case study.

This paper examines the reconceptualization of IC through a case study. Further detail of this case are provided in Barbosa-Chacón et al. (2010).

Excerpt code R-6:11-LR is read as follows: R indicates the source of the datum, in this case a student report; 6:11 indicates the report number and the number code of the part of the report; and LR is the anonymous identifier of the participating student.