This article presents an analysis of information needs and information behavior of blue agave farmers in the municipality of Tequila, Jalisco (Mexico). Nowadays we can find many different kinds of agaveros —as these farmers are commonly called in Mexico— who are classified by some characteristic features, such as property holdings, economic power, social status, and others. There are two main groups of agaveros, the independent farmers and those who rent out land for others to cultivate. Findings show that the information needs of blue agave farmers and the information resources they consult are associated with their farming activities and daily lives.

En este artículo se presenta un análisis sobre las necesidades de información y el comportamiento informativo que muestran los agricultores de agave azul del municipio de Tequila, Jalisco. Actualmente existen diferentes grupos de agaveros —como también se les conoce a esta clase de agricultores— que se distinguen por elementos característicos como la tenencia de la tierra, su poder adquisitivo y su estatus social. Destacan los agricultores independientes y los agricultores que alquilan sus parcelas, grupos de población en los que se enfocó la investigación De acuerdo con los resultados del estudio, tanto sus necesidades de información como la consulta de determinadas fuentes y recursos informativos para satisfacerlas giran en torno a sus actividades agrícolas y al desarrollo de su vida cotidiana.

The tequila maguey cactus (Agave tequilana weber) is most often used as a raw material for the production of tequila in the state of Jalisco, lying in Mexico's central highlands. The municipalities of Amatitán, Tequila and El Arenal are leading producers of this crop.

Agricultural practices used in the cultivation of blue agave had changed little since pre-Hispanic times. More recently, however, some innovative agricultural techniques based on technological and scientific progress have been implemented. These technologies became available during the so-called “tequila boom,” which began around 1996, when Mexico began exporting tequila to the world market at an unprecedented volume. This high demand led to critical over-exploitation of the agave harvest. The agave supply crisis spurred interest in the cultivation of blue agave, centered largely in the Mexican state of Jalisco. Several lines of research were launched focusing mostly on the history of agave production, its physiology, agricultural practices, associated plant diseases and pests and, of course, the importance of blue agave to the tequila industry.

Similar interest was born in the world of plastic arts, cultural spheres, the academy and social organizations with regard to the elements that comprise the agave-tequila production chain. This is seen in artistic renditions of the agave landscape, ancient tequila distilleries, the current leading brands in the tequila industry, and more recently, the iconic image of the jimador (harvester). Up until the present, however, the fundamental personage undergirding the entire productive edifice, the blue agave farmer, has been completely neglected.1

Most research on the production of tequila mention the blue agave farmer only indirectly and peripherally, largely in regard to the history of large tequila houses or socio-political movements such as the Mexican Revolution and land redistribution. None of these studies examines the work of farmers, their lifestyle, idiosyncrasies, and much less their information needs and behaviors.

Putting a finger on this informational gap about blue agave farmers is what makes this research relevant, particularly when so little is known about what information resources this population resorts to in order to meet the information needs associated with their work and daily lives. This purpose arises from the scientific principle that suggests studying the information needs and information behavior of non-academic communities, which have so far been largely neglected, specifically those residing in the Mexican agricultural sector.

This research report is divided into five main parts. In the first, we offer some background and a review of research on the topic to serve as a knowledge base; the second part describes the current state of blue agave farmers with regard to their agricultural work and local idiosyncrasies in Tequila, Jalisco; part three describes the research methodology; part four offers an analysis of results, and part five offers some general conclusions.

BACKGROUNDThe first research paper addressing the information needs and behaviors of farmers was conducted in 1985 in Nigeria by Lenrie O. Aina, who determined that the most important areas of information for this group of people are “irrigation techniques; fertilization techniques; equipment for plowing, cultivation and harvesting; and weather, climate, meteorology and cultivation techniques as per crop species, pest control and pesticides” (Aina, 1985: 38). Sometime later, Nason (2007: 20) states the following:

[...] the needs of farmers in developing nations are similar to those of their American counterparts, and include such concerns as soil, fields type, climate, access to agricultural technology, securing credit and market prices.

According Nason (2007: 22), the information resources on crops and agriculture, etc. used by farmers, include “radio and television, publications for farmers and ranchers, libraries, farming co-op services and experimental stations.”

Moreover, in 2010, the interest group of agriculture libraries of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (ifla), in conjunction with the International Association of Agricultural Information (iaald), provides that the information needs of farmers revolve around issues of fertility, soil erosion, weather conditions, fertilizers, pest and weed control, water management, farm credits, post- harvest issues, shipment, marketing and other associated matters (ifla, 2010).

In Mexico between 2009 and 2014, four master's degrees and one doctorate, whose dissertations addressed the information needs of farmers, were awarded in the Post-Graduate School of Library and Information Studies. All of these research projects examined wine makers, and their results were in some cases similar to those of the abovementioned research projects.

Blue agave farmers in Tequila, Jalisco: historic antecedentsThe earliest blue agave farmers in Tequila, JaliscoThe earliest records of human activity associated with the cultivation of blue agave in the state of Jalisco date to 1500 BC. The tombs of inhabitants often contain ritual offerings of food and some elements associated with agave cultivation (Colunga et al., 2007). These offering include delicate burnished clay vessels painted with representation of large earthenware caldrons cooking agave pencas, or leaves, and persons laden with agave hearts, which are also known as mezcal. These painted images are contemporary to agave ovens found in the Lake Sayula basin and in the foothills of Tequila amid a settlement once called Teochinchán (Colunga et al., 2007) lying within the modern municipality of Tequila.

The Teochinchán tradition,2 with its characteristic concentric structures known as Guachimontones erected in the shadow of the Tequila Volcano, seemed to hold a near commercial monopoly in the exploitation of the blue agave. Over the course of the centuries, it appears this culture carried out significant changes to the flora and fauna in order to adapt the environment to the production of blue agave and other close varieties (Dansac, 2012).

According to some accounts, the first pre-Hispanic people associated with the blue agave culture were the tiquilos, who began to domesticate agave in order to exploit diverse products, including the distillate we call tequila.

According to Jose Rogelio Alvarez (1969), the tiquilos, hence the eponym tequila, were a Nahuatl tribe who used the maguey for purposes as diverse as thatch and making beverages. Regarding the later, the earliest deink derived from agave was octli poliuhqui, or pulque.

In fact, the tiquilos would need many years to discover that distillation of the agave could make a strong alcoholic drink. It is likely that after cooking the agave, they ground it and let it ferment without actually distilling it. Distillation, of course, is what clarifies the liquid and gives it a higher alcohol content.

Spanish influence in the agave cultivation and the beginnings of mass productionBy the eighteenth century, the production process was no longer in the exclusive hands of the indigenous communities in the region and the distillation of vino-mezcal, as tequila was originally called, was largely in the hands of the Spaniards. Tequila soon was commercially available throughout New Spain along with a wide array of products shipped in from the old continent. This early commercial boom led to the expansion of agave plantations in the municipality of Tequila.

This commercial expansion caused the traditional agave cultivators to lose control of their productive lands, which were taken over by large land owners, who thereafter determined the purchase price of lands from indigenous farmers and prices of the agave harvest. Spaniards also set salaries for farm workers and other conditions of sale and export of agave products. The hegemony of the latifundio was so great in this agricultural sector that in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it had laid the economic and practical groundwork for an unprecedented agricultural project specialized in the production of agave. This type of productive plantation was unique in New Spain and the greater Americas.

Land distribution and the modernization of blue agave cultivation in TequilaBy the second and third decades of the twentieth century, information on the life of blue agave farmers in Tequila is not entirely clear. In fact, there is a lot of confusion about how this developed in comparison to previous decades. This situation arises because of the political re-accommodations carried forward after the period of armed revolutionary movements, which saw the lifestyle of farmers undergo radical change from the rural life of the grower to life in an industrial setting.

With land distribution during administration of President Lazaro Cardenas, the regional production process led by large land and distillery owners was broken. In this context and in light of the special treatment given to farmers by the state, the public discourse begins to address the creation of an agrarian social pact. In addition to meeting the Mexican Revolution's central demand of redistributing land, this policy was aimed as assimilating rural civil society into the new regime.

As for croplands of these agave farmers, land distribution entailed the organization of landowners and farmers, crop rotation and diversification schemes, introduction of new crops, seed selection, mechanization and fertilizer; and the establishment of institutes, laboratories and experimental farms. The full exploitation of crops was also promoted, and agricultural credits for small landowners and farmers were made more widely available.

Blue agave farmers in the twenty-first centuryAccording to the most recent population and housing census (conducted in 2010), the town of Tequila has 40,697 inhabitants, of which 49.5% are men and 50.5% are women.3 The percentages of those who work directly or indirectly in the cultivation of blue agave and to what degree are as follows: 20% cultivate agave exclusively; 40% alternate cultivation with other earning activities, 10% cultivate agave occasionally; while 30% no longer grow or otherwise work in the agave industry or never have. Number of blue agave farmers of the municipality devoted exclusively to the cultivation of blue agave has declined considerably. This phenomenon results from a series of events initiated in the year 1996 during so-called tequila boom. In the following years, this series of events would have direct, significant influence in shaping the informational profile of these farmers.

The tequila boom and the crisis of overexploitation of blue agaveBy 1996, the production of tequila within the official Appellation of Origin4 had peaked, not only within the country but also beyond its borders. As cited in official reports and diverse statistics to September 2012, the production of tequila nationally came to 196.6 million liters. Similarly, export numbers hit 127.4 million liters.5 This high demand drove production and consumption of blue agave to unprecedented levels. In 2007, the consumption of blue agave to make tequila reached 417,000 tons, a level that grew to 676,100 tons in 2012. The municipality of Tequila led all regional producers that year with 11,000 tons.6

Today, blue agave plantations within the official Appellation of Origin comprise a productive inventory of more than four million agave plants, planted between 2000 and 2006. Of this inventory approximately 80,000 tons7 were produced in the town of Tequila, which is to say that in just two years the production there increased by almost 10%.

This led to several situations, the first of which, and perhaps most significant, was the crisis of overproduction and over-exploitation of agave.

The crisis of over-exploitation and changes in production systems of blue agave farmers: the emergence of the needs for information on the environmentDue to high sales of tequila (today standing at around 10 million liters annually), most agave farmers of the municipality of Tequila joined in to start mass production in order to sell their crop to large tequila houses. To this end, acreage under cultivation in the municipality increased considerably, often in detriment to other crops such as corn and beans. From 1990 to 1997, land devoted to other crops declined sharply from 62,000 to 50,000 acres, and by 2000 to only 45,000 acres. The demand for blue agave even led some farmers to attempt to experiment with shortening ripening time from the normal seven or eight, to only four years.

In the face of this rising demand, most farmers had to alter their habitual production systems. From pre-Hispanic times to the present day, cultivation of blue agave had provided people with rope, needles, fodder, fertilizer, building materials and other products, genuinely constituting an almost unbeatable means of subsistence, independent from growing maize or raising livestock, because agave farmers never had any need to compete for the most productive, flat bottom lands, and there were never any incentives to move away from traditional growing methods. In other words, the age-old task of growing agave was always a family matter handed down from earlier generations.

Before the overexploitation crisis, cultivation of the agave plant required only minimal labor. In most families, work was divided among the members and included such tasks as cutting suckers, hoeing the ground to oxygenate the soil and cultivation of maize, beans and squash. With the need to grow more agave, much of this manual labor was almost completely modernized and mechanized.

A series of phenomena ensued from this situation in agave cultivation that still persist; for example, many of the once seasonal tasks became year-round work performed only by farmers considered skilled specialists working in harvest crews, while other crews worked in clearing land, planting and applying agrochemicals to production fields. Additionally, these changes drove social and economic phenomena such as a growth of skilled labor, which resulted in widening of social difference among farmers, internal and external emigration and immigration, falling salaries for unskilled laborers, truncated social interaction of farmers within their communities, interaction between experts from diverse disciplines, training to improve performance of certain activities, organization of ejido groups, unemployment, marginalization, social decay and acculturation, among many others.

As a result of these phenomena, blue agave farmers began to develop series of information needs, which still exist to this day, and a pattern or profile of informational behaviors, as they urgently worked to adapt to the synergy that the new economic and productive environment had brought about. Ultimately, two events would as largely determine the information profile of blue agave farmers. The first was the official designation of the municipality of Tequila as a pueblo magico, or magic town, and the second was the unesco declaration of the agave production region as a world heritage site.

From tequila boom to the ruin of the agave farmerIn the context described above, farmers in Tequila and the greater agave growing region planted agave without any significant restriction. Moreover, many craftsmen and industrial workers within the large tequila companies left their jobs to join the ranks of planters. Even some professionals and building and automotive workers were caught up in the so-called “blue-gold fever.” Interestingly, many migrant workers who habitually traveled to the United States would choose to remain and work in the agave region. Hearing stories of the money to made from family and friends, others already residing “across the river” came back to swell the ranks of farmhands.

By those years, the price of agave reached $40.00 per kilo,8 which in view of the many tons of product purchased by tequila producers meant, unprecedented returns for farmers and a significant boost to their purchasing power and lifestyles, while also driving up their expectations for continued high earnings.

The boom times, however, would not last. The large tequila distilleries and local and federal governments teamed up to depress agave prices artificially to no one's benefit but their own.

In 2006 the price of agave fell precipitously to as low as $16.00 per kilo, and currently the price ranges between $0.50 and $3.00, at less than 50% of the previous ten-year average. What's more, bank interest rates rose dramatically, which was very hard on farmers carrying debt.

These factors and the depletion of soil due to over production conspired to put an end to the tequila boom after a ten-year heyday. As agave farming became less profitable, many locals had to return to their former lives, some even selling off portions of their lands or renting it to tenants. Some sold off all of their lands and returned to their former jobs in the large distilleries, while others with fewer options swelled the ranks of the unemployed.

Tequila, Pueblo MágicoIn 2003 the Mexican Tourism Ministry included the town of Tequila in the official list of pueblos mágicos, or magic towns. These towns are considered especially attractive and ripe to for tourism development.

In the first four years after this designation, locals received funding of around 1.5 million dollars from the oversight committee (Gómez Arriola, 2009), for the purpose of renovating the town's downtown district and creating other service oriented infrastructure.

The entry of Tequila into the magic towns program of the Tourism Ministry came about largely due to the efforts of a small group of entrepreneurs, owners of the largest Mexican tequila distilleries (Cuervo, Sauza and Herradura). These business leaders hoped to promote their products by associating the industry more closely with its historical and cultural roots, which in many ways have come to represent the traditions and customs of the nation as a whole.

Some of the most important reconstruction works in the village include the restoration of the urban image, architectural infrastructure works, public lighting, drainage, paving streets, installing underground electric power and telephone wiring, public gardens and trees, artistic lighting of monuments and many other projects. Additionally, the municipal government invested in the construction and renovation of schools, expansion of the Technological Institute and promotion of the Guachimontones archaeological ruins and the Cathedral of St. James Apostle.

With its designation as a magic town and the concomitant influx of public monies, Tequila soon became the third most important tourist attraction in the state of Jalisco, behind only the state capital Guadalajara and the seaside resort of Puerto Vallarta. These developments served to spearhead the tequila region's inclusion in the unesco list of World Heritage Sites.

unesco declaration of the agave landscape as a World Heritage SiteThe unesco declaration of the agave landscape as a came shortly after Tequila's inclusion in the Tourism Ministry's magic town program and amid the agave over-exploitation crisis. The Agave Landscape World Heritage Site comprises an area of 38,658 hectares of agave plantations lying between the Tequila Volcano and the deep Rio Grande River valley, a rich landscape imbued with history, and cultural and artistic delights. Archeological remains of the Guachimontones people and ancient tequila distilleries, known locally as taverns, also lie within the site along side of modern tequila distilleries and diverse colonial buildings, many of which were restored under the pueblo mágico program. The Santiago Apostle Cathedral is also a major tourist attraction lying within the site (Gómez Arriola, 2006).

In light of the appeal of the municipality of Tequila, which lends its name to the world-famous distillate, local and state tourism investment began to flow into the region, which seemed especially rich in architectural and natural beauty, and history. Significant investments were made in restoring the town of Tequila and erecting new distilleries, which offer a variety of tours to the swelling ranks of both foreign and national tourists. Other tourist attractions include train and bus tours and even hot air balloon rides.

The regions soon became a magnet not only for national and foreign tourists, but also as for the films, television and advertising industries, which were delighted with the great variety and beauty locations. This development brought is a wave of artists, writers, actors, poets, painters and others who can be seen in the newly opened hotels, restaurants, museums and entertainment centers. With this influx of outsiders, the locals have changed their habits, manner of dress, speech patterns and many other things in a process of acculturation.

In view of these changes and their economic and labor needs, many agave farmers were driven away from their ancestral agave culture and the associated lifestyle, ultimately embracing the emerging changes in social organization occurring all around them. As such, many former agave farmers currently work as taxi drivers, craft sellers, tourist guides, police and hotel staff. Those with more education have found work as authorized tourist guides, bank staff, office workers, cultural promoters, small business operators, receptionists and other kinds of formal employment.

Just as is the case described in the section on the information needs of agave farmer within the new environment, the process of incorporating farmers into their new jobs and into the new tourist-cultural environment led to the emergence of other information needs, which also serve to establish the current information profile of this population group.

The following section provides an analysis of the current condition of blue agave farmers in the municipality of Tequila, Jalisco, and their information profile derived from the events related herein.

CURRENT CONDITION OF BLUE AGAVE FARMERS IN TEQUILA, JALISCOUp until only a few years ago, many believed that the blue agave spontaneously grew in the wild without need of any human intervention or farming techniques. More recently, however, it has become well understood that agave cultivation requires quite a lot of labor both in the field and in the distillery. Very little is known about the lives of agave farm workers, who in the twenty-first century continue to cultivate the agave in the way it was done by the early inhabitants of the region.

While the job market is strong, the living conditions of workers have declined since the heyday of the early 1990s. It seems the large tequila distilleries are happy to maintain a workforce, while doing very little to improve their socio-economic conditions. Some companies, for example, have since 2000 offered woefully underpaid 100-day contracts to distillery workers and agave farmers, without providing benefits such as social security, vacation or Christmas bonus.

In such circumstances, many of these farmers have opted for other forms of paid work, such as selling handicrafts and souvenirs or developing some line of distinct work.

However, some agave farmers have managed to take on the new market conditions and sell their agave production directly to several large tequila companies, thereby escaping the trap of working for low wages. Many of these farmers have achieved better living conditions and better hopes for future security, while becoming key suppliers to the large tequila distilleries.

While the introduction of technology and science to the field of agave cultivation has helped expand the lands under cultivation, improve yields and maximize productivity, the specialized skills of certain agaveros have not been displaced.

In any event, most agave farmers have had to make significant adjustments in order to deal with the changing conditions. Unlike in days past, tequila is big business, which entails everything one might expect from a major industry. In many cases, for example, these agave farmers have had to attend courses and workshops in order to learn about new cultivation techniques, pest control and plant diseases.

Finally, some agave farmers are better-off because they have inherited growing operations that supply agave to new distilleries. These relatively wealthy agave farmers, in contrast to those who can offer only labor, have left off the production of agave to some degree, and have begun employ their specialist colleagues to muster farming crews working under the aforementioned 100-day contracts.

The circumstances of these agave farmers in the context of the social, cultural and economic changes occurring in the town of Tequila, has prompted discussion regarding the socio-economic stratification of the universe of blue agave farmers. This stratification appears to occur along the following fault lines:

- a)

Landholding;

- b)

Acreage under cultivation;

- c)

Commercial relationship with large tequila distilleries;

- d)

Socio-economic and cultural status of farmers, and

- e)

Life project

In this light, it appears there are today six distinct types of blue agave farmers:

- 1.

Agave businesses owner;

- 2.

Independent agave producers;

- 3.

Agave farmers who rent out their parcels;

- 4.

Agave farmers who work for tequila distilleries;

- 5.

Day laborers, and

- 6.

Female blue agave farmers

For purposes of this research, only independent farmers and farmers who rent out their plots were considered, since these two types of agave farmers have somehow been able to combine traditional agave production practices with the tools and techniques of modern agriculture. Moreover, these two groups are the best representatives of the foundation of agave production.

In accord with our earlier statements in this section, it appears the information profile of these farmers is more representative of the current state of the overall population of farmers. In light of the elements listed above, the following is a general description of these farmers:

Independent growers:

- a)

Own their land;

- b)

Have between 15 and 20 hectares under cultivation;

- c)

Sell crop directly to the large tequila distilleries;

- d)

Some have professional studies; high annual incomes; travel frequently; high buying power; belong to some organizations; often attend local events centered on blue agave, etc.

- e)

They wish to buy more land in order to plant more blue agave and sell it to distilleries.

Farmers who rent out their lands:

- a)

Most own their lands though some are middle men;

- b)

They rent out between 5 and 10 hectares;

- c)

They rent their lands to large tequila distilleries and in some cases to independent growers;

- d)

Their annual income are in the middle-low range; some raise cattle, other work in the tourism jobs, some have tequila and souvenir stores, others drive taxi, they have mid-level education, they have medium purchasing power; they buy cars; clothes, tequila; they travel to Guadalajara, Colima, Tepic, and other areas in the north of the country, etc.

- e)

They wish to cultivate their lands themselves and sell the crop directly to large tequila distilleries.

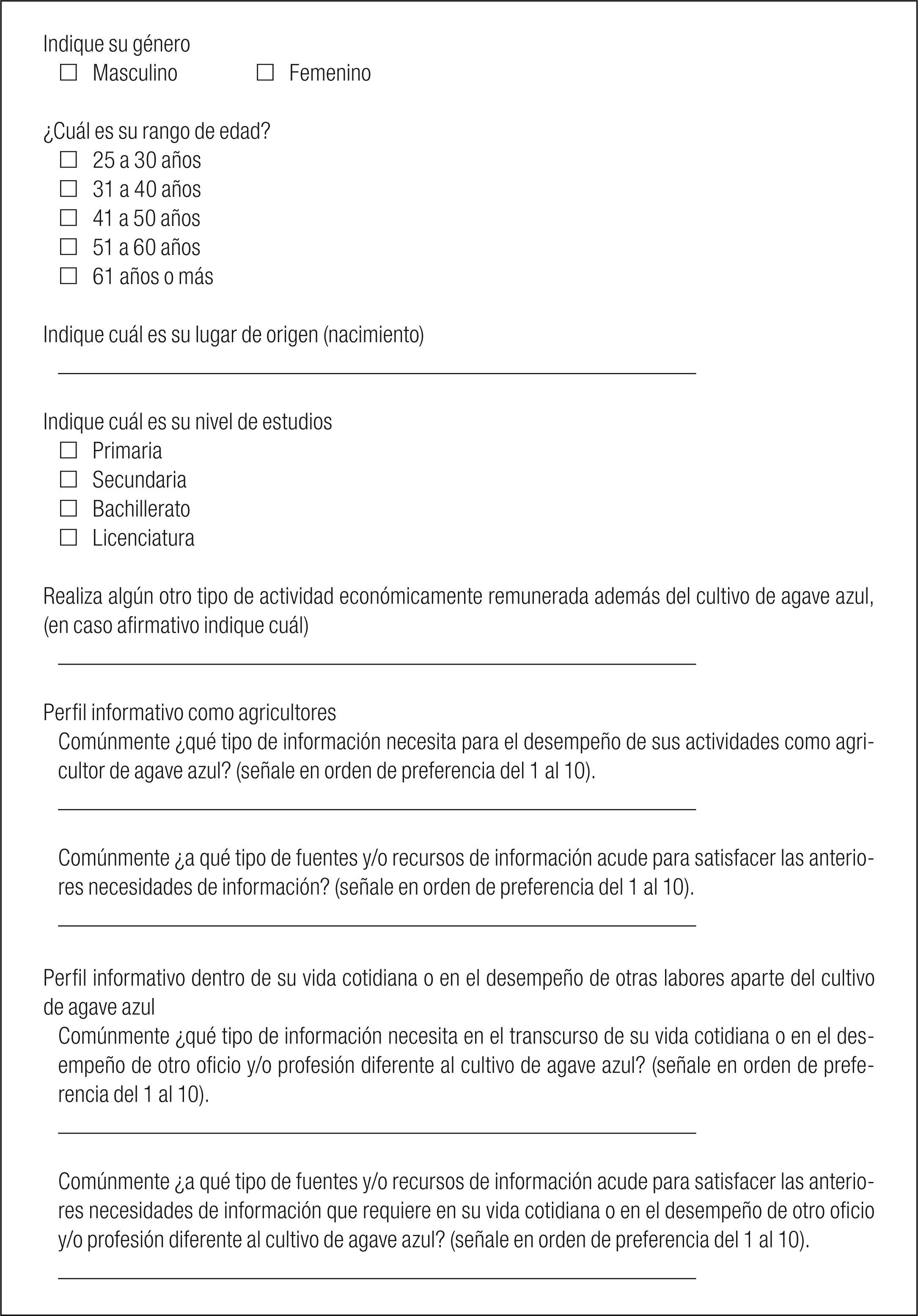

This research is of the exploratory-descriptive type. In the exploratory phase, an initial visit was made to the municipality of Tequila, Jalisco, and contacts with key sources were established. On the basis the observation and contacts established, the descriptive phase determined the following:

- •

The economic-labor and socio-cultural context of the municipality of Tequila directly influences the development of a typology or unofficial hierarchy of today's blue agave farmers.

- •

According to the typology established, the informative profile of the sample of farmers was determined on the basis of their labor, economic and socio-cultural conditions.

Literature review: A review of the relevant literature was performed.

Field study: Two visits were made to the municipality of Tequila, Jalisco, as follows:

- •

Second visit: Preliminary interviews with sources were performed and recorded.

- •

Third visit: The structured instrument (Appendix), specifically designed for the target sample of the research universe was applied.

The procedure to identify the population and corresponding sample was achieved by consulting the Statistical and Geographic Information System of Jalisco to extract the number of permanent and temporary individuals working in the agricultural sector in the municipality of Tequila who are registered with the Mexican Social Security Institute. The number of farmers registered in this way came to 285. On the basis of the information above, approximately 80% of these individuals are devoted to the cultivation of blue agave, a figure of 228.

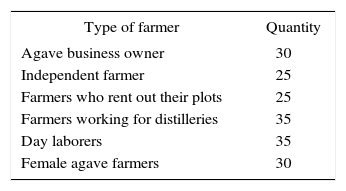

SampleOf this population of 228 agave farmers, a total of 180 farmers were actually found (80%). On the basis of the typology established, the number of farmers in each category break down as show in the following table:

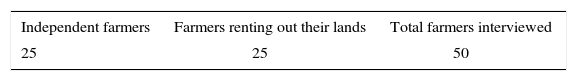

For the specific effects of this research, only the 25 farmers who rent out their land and the 25 independent farmers were examined.

RESULTSGeneral dataAs stated above, the first step of the methodology entailed locating five key sources for each type of farmer. In this case, we located five independent farmers and five farmers who rent out their plots. Then each of these initial contacts provided the contact information of four additional farmers, bringing the sample total to 50 farmers, as shown in Table 2 below.

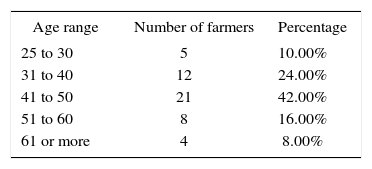

Of the 50 farmers interviewed, all were men ranging from 25 to 60 years-old, distributed as shown in the following table:

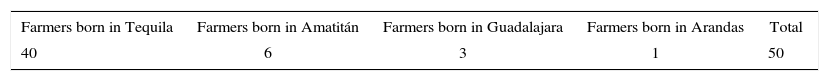

Of the sample interviewed, all were agave growers in the municipality of Tequila, Jalisco, although some were not originally from the zone. The total number of the sample born within the municipality of Tequila came to 40, while 5 were from Amamtitán, 3 from Guadalajara and one from Arandas (Table 4).

As for the level of education of those interviewed, 12 reported having completed primary school, 20 report finishing secondary school, 12 finished high school, while six hold university level degrees, though only three of these hold degrees in fields related with agronomy (Table 5).

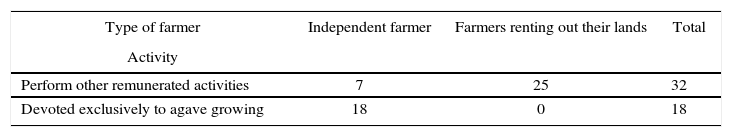

Moreover, 32 of these farmers engage in some other financially remunerated activity. Twenty-five of these belong to the group farmer who rent out their plots, while seven are from the independent farmer group.

Eighteen farmers are devoted solely to the cultivation of agave: all of these came from the independent farmer group (Table 6).

Analysis of resultsAfter establishing the current status of blue agave farmers in Tequila, Jalisco, and in order to determine the sample population to be analyzed, this section present the analysis of the results obtained from the information gathering instrument (Appendix).

Taking into account the two types of farmers in the sample, each section presents the results obtained in two parts. The first part examines the information needs and behaviors in relation to their activities as blue agave farmers, while the second part

refers to these variables in relation to their daily lives, social context, idiosyncrasies and complementary economic activities. The results will be presented in tables and graphs to facilitate understanding.

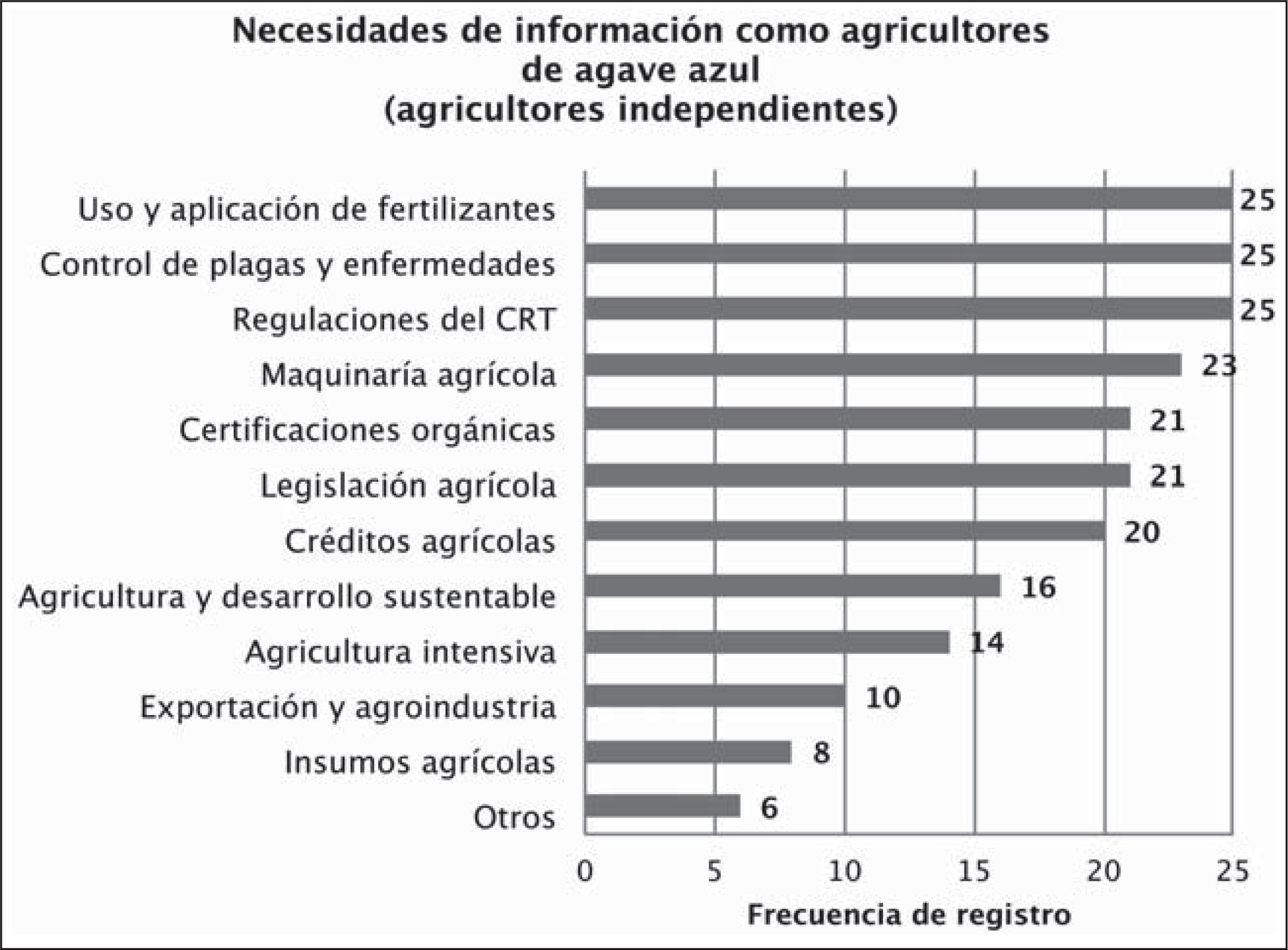

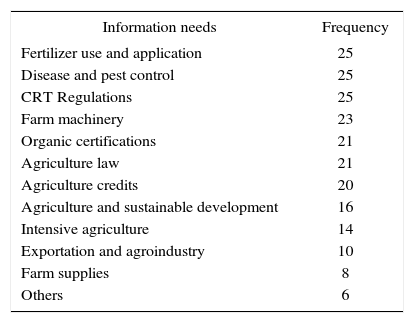

Information profile of the independent farmersInformation needs of blue agave farmersAs the results indicate, the most frequent information needs of independent farmers, with 25 registers each, include the application of fertilizers, pest and disease control, and regulations of the Tequila Regulatory Council. This area is followed by farm machinery (23 tallies); organic certification and agricultural legislation (21 tallies); agricultural loans (20 tallies); agriculture and sustainable development (16 registers); intensive agriculture (14 tallies); export and agro-business (10 tallies); agricultural supplies (8 tallies) and miscellaneous (6 tallies). These frequencies are shown in Table 7 and Figure 1 below.

| Information needs | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Fertilizer use and application | 25 |

| Disease and pest control | 25 |

| CRT Regulations | 25 |

| Farm machinery | 23 |

| Organic certifications | 21 |

| Agriculture law | 21 |

| Agriculture credits | 20 |

| Agriculture and sustainable development | 16 |

| Intensive agriculture | 14 |

| Exportation and agroindustry | 10 |

| Farm supplies | 8 |

| Others | 6 |

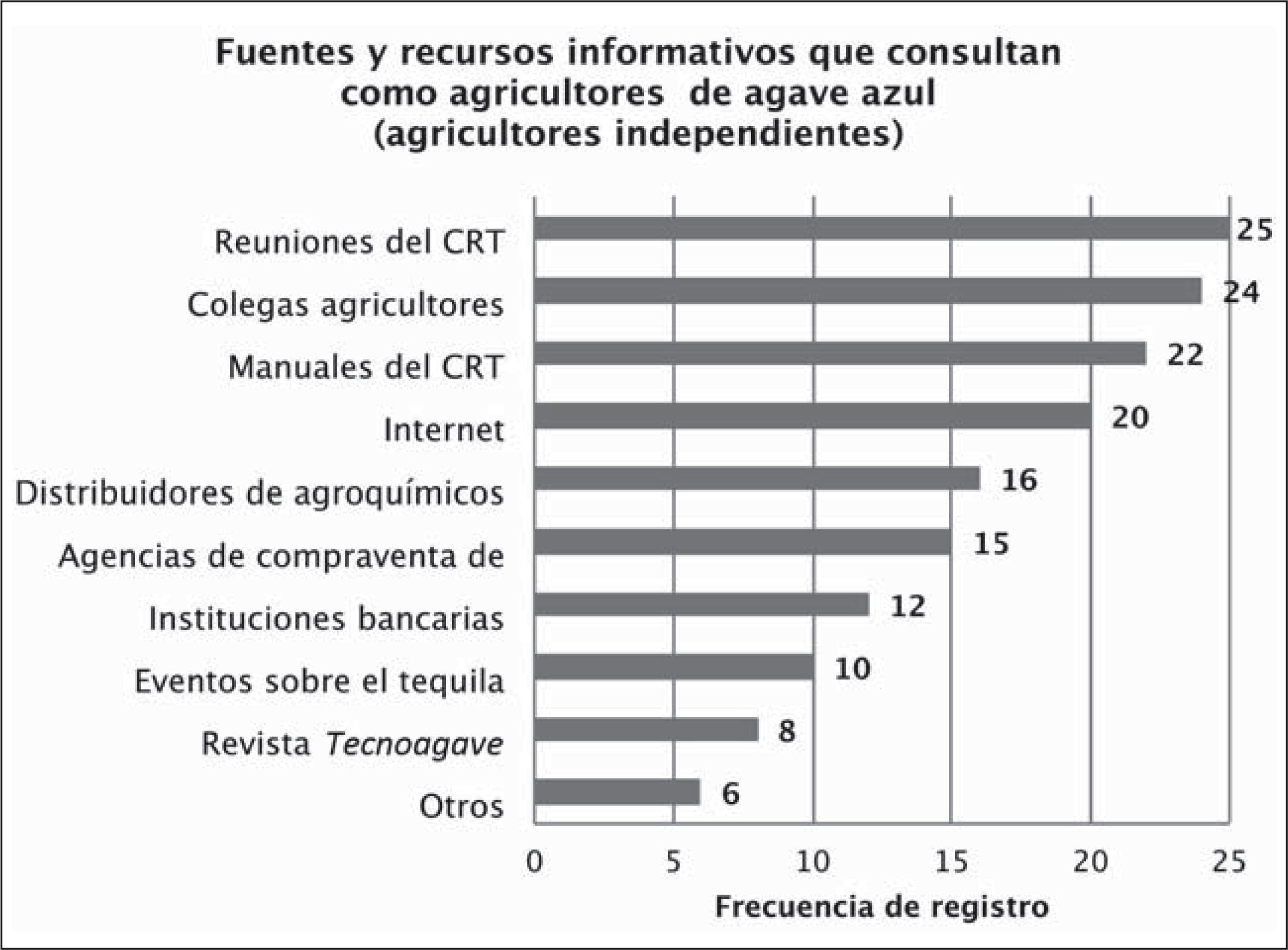

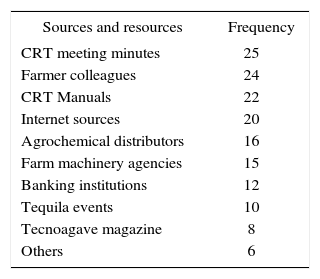

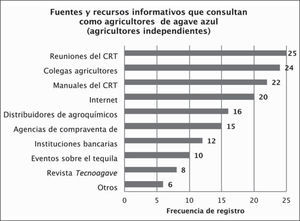

Moreover, sources and resources consulted by independent farmers to meet their information needs include the minutes of crt meetings (25 tallies); farmer colleagues (24 tallies); crt manuals (22 tallies); internet sources (20 tallies); agrochemical distributors (16 tallies); farm machinery sales agencies (15 tallies); banking institutions (12 tallies); tequila related events (10 tallies); Tecnoagave magazine (8 tallies) and other miscellaneous sources (6 tallies). These results are shown in Table 8 and Figure 2.

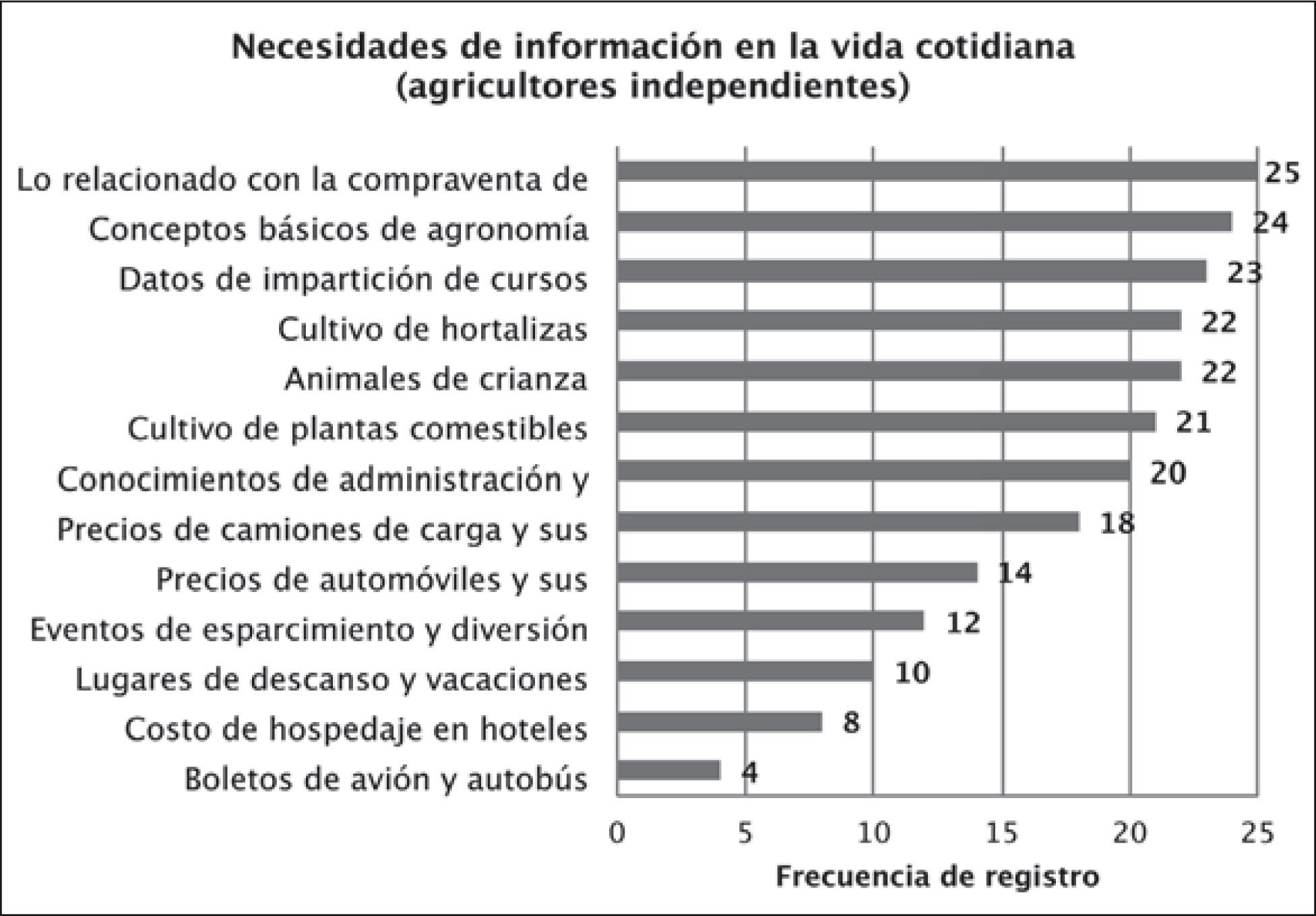

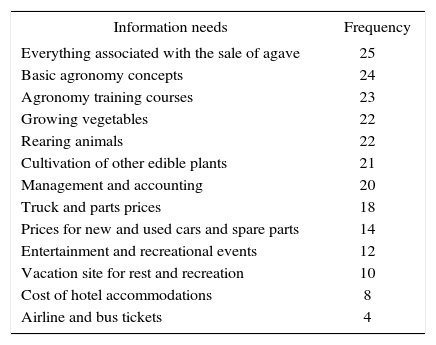

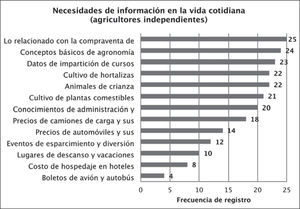

The information needs associated with daily life reported by independent agave farmers include the following areas: Everything associated with the sale of agave (25 tallies); Basic agronomy concepts (24 tallies); Agronomy training courses (23 tallies); Growing vegetables and rearing animals (each with 22 tallies); Cultivation of other edible plants (21 tallies); Management and accounting (20 tallies); Trucks and parts prices (18 tallies); Prices for new and used cars and spare parts (14 tallies); Entertainment and recreational events (12 tallies); Vacation site for rest and recreation (10 tallies); Cost of hotel accommodations (8 tallies) and Airline and bus tickets (4 tallies). These data are shown in Table 9 and Figure 3.

| Information needs | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Everything associated with the sale of agave | 25 |

| Basic agronomy concepts | 24 |

| Agronomy training courses | 23 |

| Growing vegetables | 22 |

| Rearing animals | 22 |

| Cultivation of other edible plants | 21 |

| Management and accounting | 20 |

| Truck and parts prices | 18 |

| Prices for new and used cars and spare parts | 14 |

| Entertainment and recreational events | 12 |

| Vacation site for rest and recreation | 10 |

| Cost of hotel accommodations | 8 |

| Airline and bus tickets | 4 |

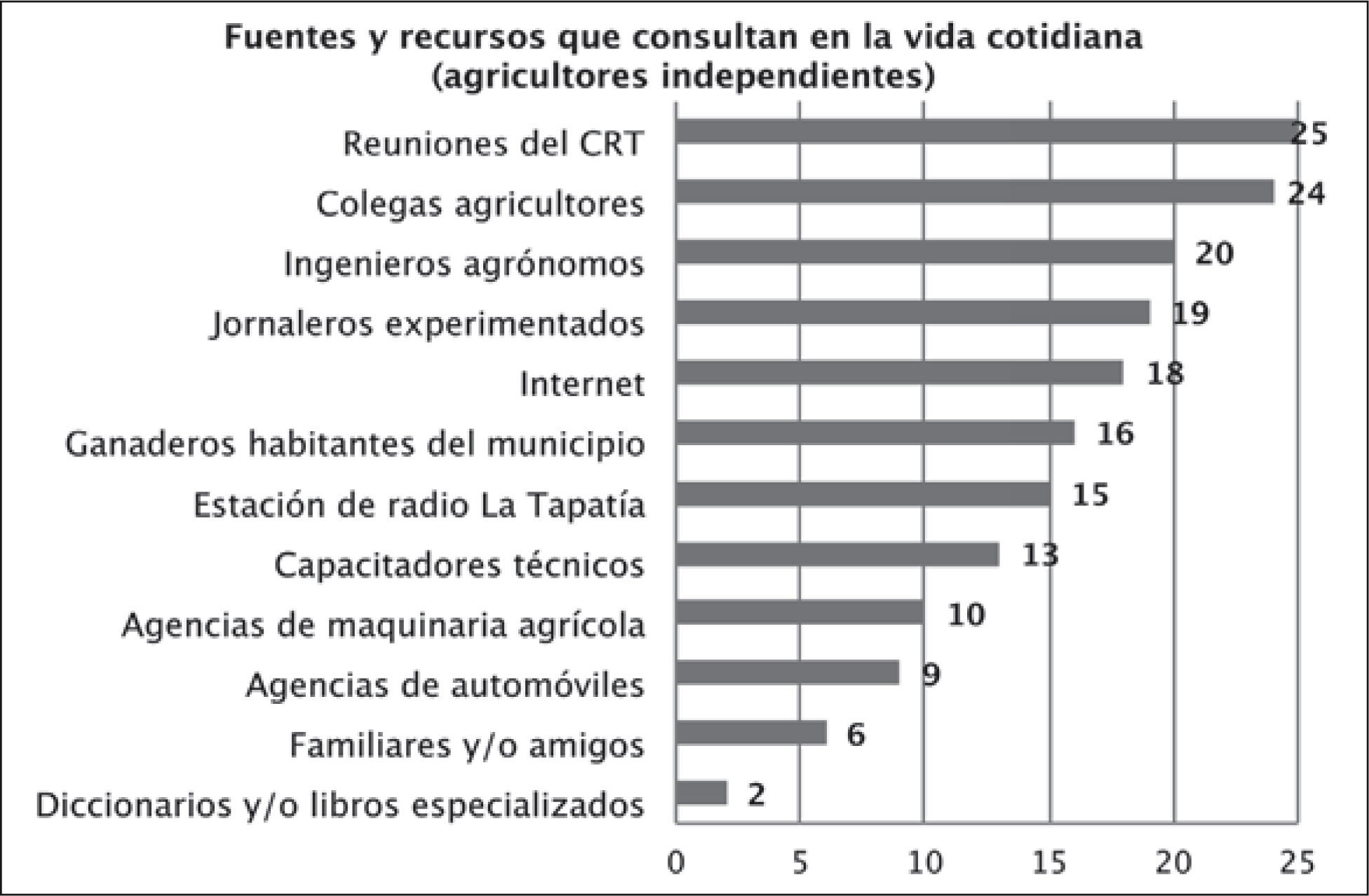

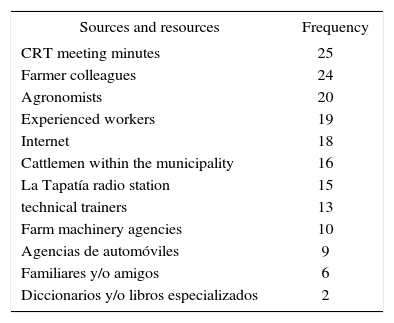

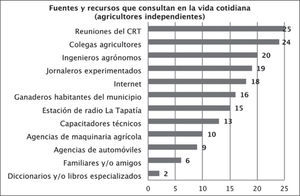

To meet these information needs, independent farmers make use of the following sources and/or resources with the following frequencies: crt resources (25 registers), followed by farmer colleagues (24 tallies); agronomists (20 tallies); experienced workers (19 tallies); internet (18 tallies); cattlemen within the municipality (16 tallies); La Tapatia radio station (15 tallies); technical trainers (13 tallies); farm machinery agencies (10 tallies); car dealerships (9 tallies); family and/or friends (6 tallies) and dictionaries and/or specialized books (2 tallies). These results are shown in Table 10 and Figure 4.

| Sources and resources | Frequency |

|---|---|

| CRT meeting minutes | 25 |

| Farmer colleagues | 24 |

| Agronomists | 20 |

| Experienced workers | 19 |

| Internet | 18 |

| Cattlemen within the municipality | 16 |

| La Tapatía radio station | 15 |

| technical trainers | 13 |

| Farm machinery agencies | 10 |

| Agencias de automóviles | 9 |

| Familiares y/o amigos | 6 |

| Diccionarios y/o libros especializados | 2 |

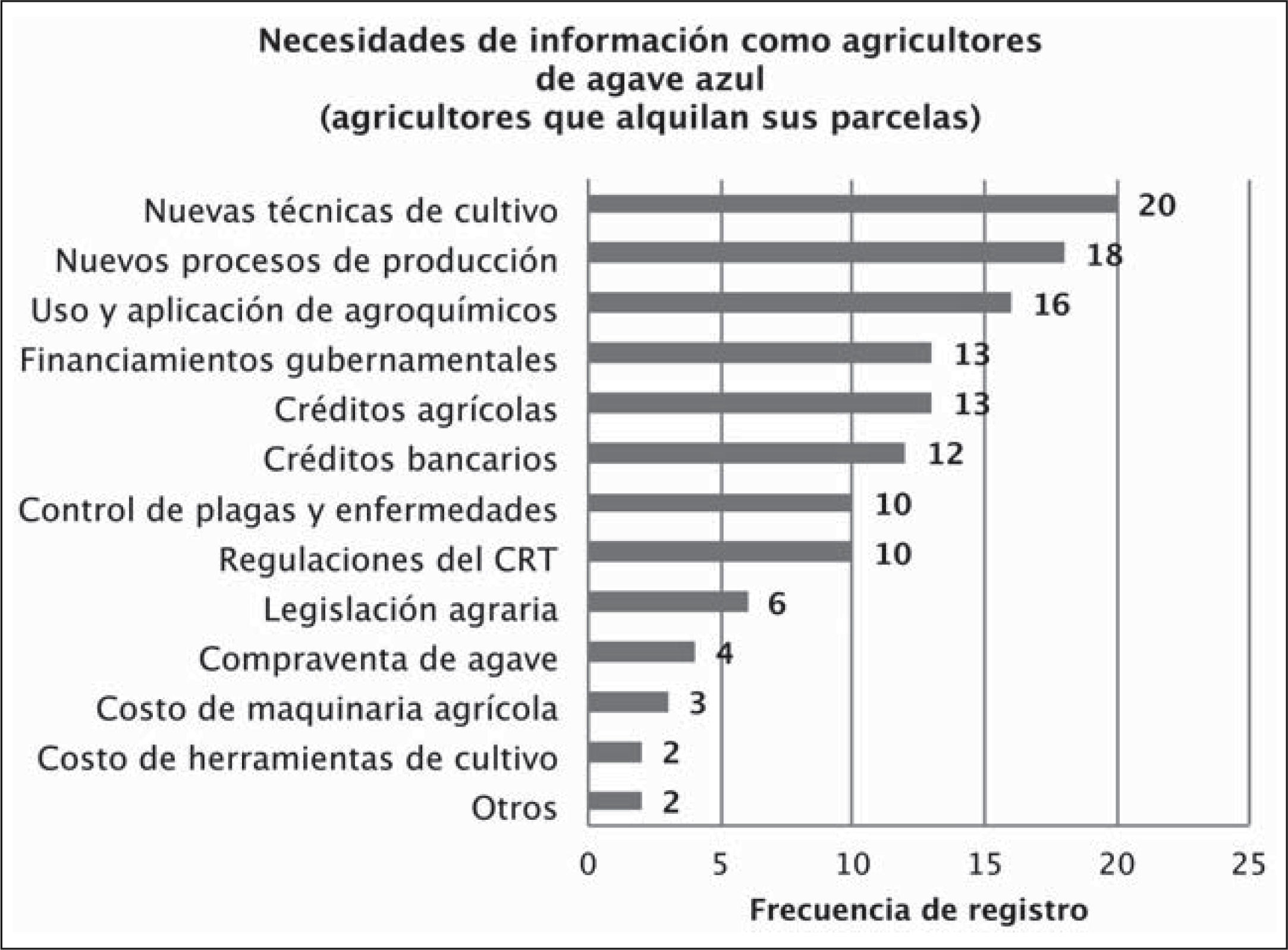

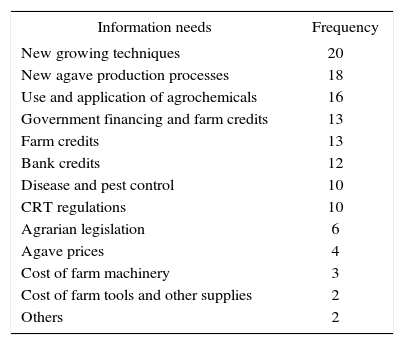

The results of interviews of farmers who rent out their lands, show the following the information needs: use and application of new growing techniques (20 tallies); new agave production processes (18 tallies); use and application of agrochemicals (16 registers); government financing and farm credits (13 tallies each); bank credits (12 tallies); disease and pest control, and crt regulations (10 tallies each); agrarian legislation (6 tallies); agave prices (4 tallies); cost of farm machinery (3 tallies); cost of farm tools and other supplies (2 tallies each) Table 11 and Chart 5 show the breakdown of these results.

| Information needs | Frequency |

|---|---|

| New growing techniques | 20 |

| New agave production processes | 18 |

| Use and application of agrochemicals | 16 |

| Government financing and farm credits | 13 |

| Farm credits | 13 |

| Bank credits | 12 |

| Disease and pest control | 10 |

| CRT regulations | 10 |

| Agrarian legislation | 6 |

| Agave prices | 4 |

| Cost of farm machinery | 3 |

| Cost of farm tools and other supplies | 2 |

| Others | 2 |

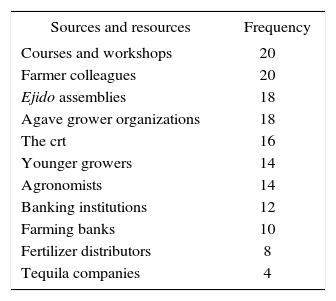

The sources and/or resources these farmers consult with greatest frequency in order to satisfy information needs are as follows: courses and workshops (20 tallies); farmer colleagues (20 tallies); ejido assemblies and agave organizations (18 tallies each); the CRT (16 tallies); younger agave grower with agronomy degrees (14 tallies each); banking institutions (12 tallies); farm banks (10 tallies); fertilizer distributors (8 tallies); and tequila distilleries (4 tallies) Table 12 and Chart 6 show these results).

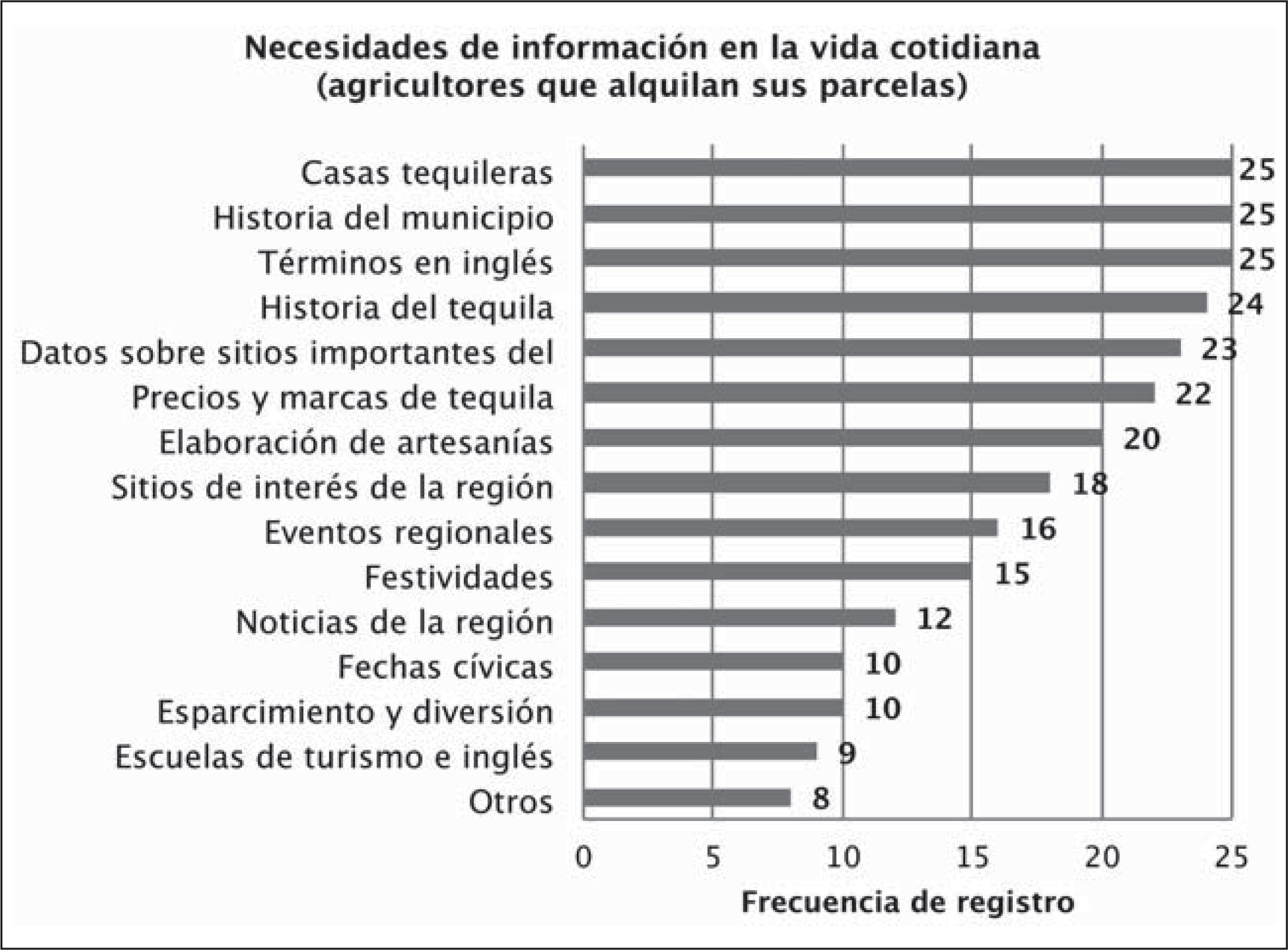

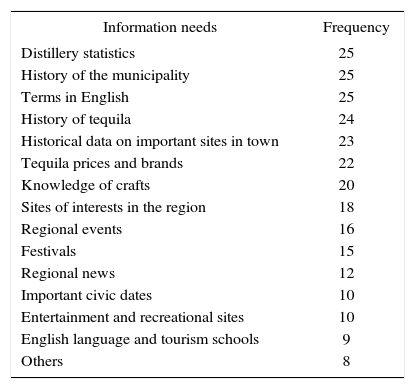

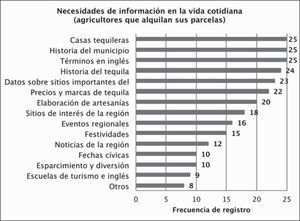

As was observed in the section of the current status of blue agave farmers in Tequila, Jalisco, nowadays those farmers who rent out their plots do not earn a living exclusively from the harvest of blue agave. In this sense, their lives, idiosyncrasies and aspirations have had to adapt to this new situation. Their most frequent information needs are as follows: distillery statistics, history of the municipality and terms in English (with 25 tallies each); history of tequila (24 tallies); historical data on important sites in town (23 tallies); tequila prices and brands (22 tallies); knowledge of crafts (20 tallies); sites of interests in the region (18 tallies); regional events (16 tallies); festivals (15 tallies); regional news (12 tallies); important civic dates and entertainment and recreational sites (10 tallies each); English language and tourism schools (9 tallies) and others (8 tallies) Table 13 and Chart 7 show these data.

| Information needs | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Distillery statistics | 25 |

| History of the municipality | 25 |

| Terms in English | 25 |

| History of tequila | 24 |

| Historical data on important sites in town | 23 |

| Tequila prices and brands | 22 |

| Knowledge of crafts | 20 |

| Sites of interests in the region | 18 |

| Regional events | 16 |

| Festivals | 15 |

| Regional news | 12 |

| Important civic dates | 10 |

| Entertainment and recreational sites | 10 |

| English language and tourism schools | 9 |

| Others | 8 |

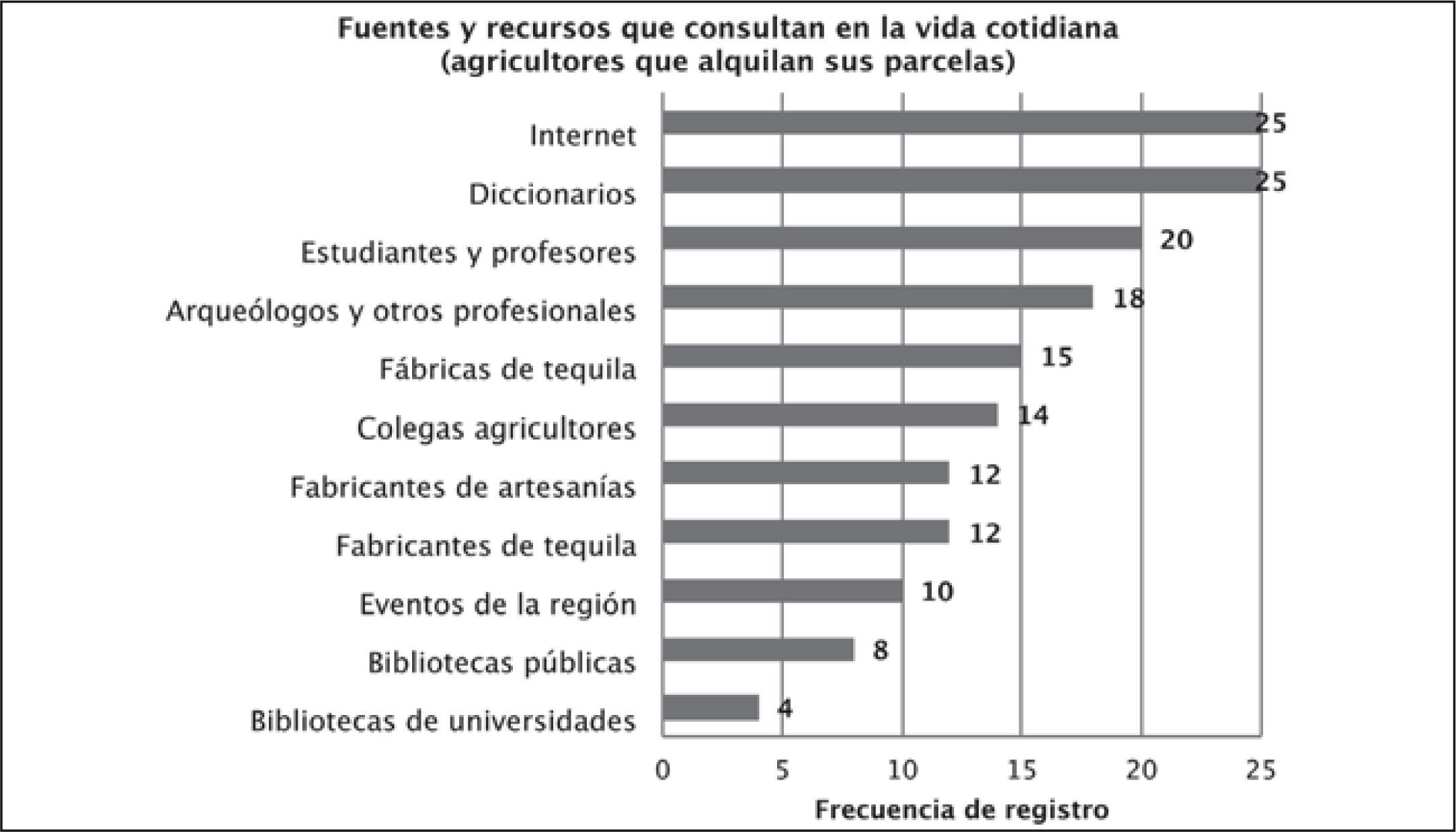

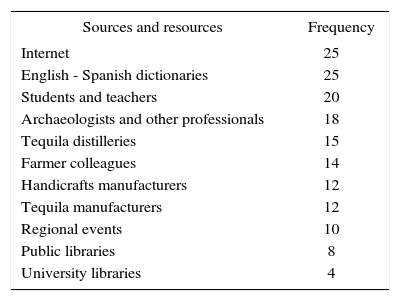

The sources and resources used by these farmers to meet their information needs are from more to least frequent as follows: internet and English - Spanish dictionaries (25 tallies each); students and teachers living of the municipality (20 tallies); archaeologists, anthropologists and historians in the region (18 tallies); tequila distilleries (15 tallies); farmer colleagues (14 tallies); handicrafts and tequila manufacturers (12 tallies each); regional events on agave and tequila (10 tallies); public libraries (8 tallies) and university libraries (4 tallies).Table 14 and Figure 8 show these data.

| Sources and resources | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Internet | 25 |

| English - Spanish dictionaries | 25 |

| Students and teachers | 20 |

| Archaeologists and other professionals | 18 |

| Tequila distilleries | 15 |

| Farmer colleagues | 14 |

| Handicrafts manufacturers | 12 |

| Tequila manufacturers | 12 |

| Regional events | 10 |

| Public libraries | 8 |

| University libraries | 4 |

Currently there are marked differences in the social, economic, labor and cultural levels of the diverse blue agave growers in Tequila, Jalisco. This is especially true for the two sample groups examined in this study.

On one hand, we find the independent farmers, who because of their large land holdings, can compete with large tequila distilleries or, in fact, serve as their sole supplier of agave. This position generates significant earnings, which is closely associated with strong purchasing power. Consequently, these growers have undergone significant changes in terms of lifestyle, social status, idiosyncrasy and life project.

In contrast to the above, are those farmers who rent out their small holdings because they do not have the capital or industrial capacity to exploit forcing them to abandon agave work partly or wholly, and to take on alternate jobs and adapt to the new economic climate brought about by the pueblo magico program and the unesco's inclusion of the region in the lists of World Heritage Sites. This move away from their traditional agave growing activities has transformed their lifestyle, idiosyncrasy, social status and aspirations, while also exerting an effect on their information needs and behavior.

It is evident that the information needs of independent farmers lie in the area of acquiring skills and knowledge to improve their farm operation and the land itself.

As such, these farmer consult sources and resources that are directly associated with these needs. These resources include persons, manuals, institutions, and secondary and tertiary sources involved in the field, which is to say anything that might be of help.

For the second group, taking on work in alternative areas, with the concomitant change in their social status, has generated information needs that go beyond farming techniques. For example, those agave farmers who work in tourism jobs have had to consult an entirely distinct class of information in order to secure certification.

In this light, it is clear that the information needs generated and subsequently met have provided these farmers with a wealth of new knowledge helping them more effectively cope with the process of adapting to their new environment, lifestyle and idiosyncrasy, among others.

Moreover, while many sources and resources consulted are secondary sources, such as dictionaries, there are also many other resources that are first hand, such as books and libraries, whose information is more reliable.

Finally, one can infer that the information needs in both types of farmers are determined largely by their respective social, economic and cultural contexts with which they must interact and adapt in order to fully develop all aspects of their lives.

For a long time it was believed this plant grew wildly without need of any care, treatment or conservation.

A complex ancient society likely existing from 300 BC to 900 ad in the region north of modern Guadalajara.

Information obtained from the Sistema de Información Estadística y Geografía de Jalisco (2012: 40).

This category included 125 municipalities in Jalisco, eight in Nayarit, seven in Guanajuato, thirty in Michoacan and eleven in Tamaulipas. Michoacan is the is the second largest tequila producer behind Jalisco.

Datas obtained from the Tequila Regulatory Council (http://www.crt.org.mx/EstadisticasCRTweb/)