The information age requires information policies to guide its global articulation. Brazil has attempted to answer this call with policies that despite their good intentions have not obtained desired results. datasus, the Brazilian health information system, operates under policies that seem to be designed without considering the latest discoveries of Information Science regarding the informational nature of humans. This article discusses several information behavior models and theories that must be considered when formulating information policies and proposes an “Information Field” model containing guideposts for their construction.

La era de la información necesita políticas de información para la articulación global; Brasil propuso políticas que, a pesar de sus buenas intenciones, no consiguen los resultados deseados. Es el caso de datasus, sistema de información de salud brasileño. Tales políticas ignoran los descubrimientos de la ciencia de información sobre la naturaleza del sujeto informacional. Este artículo discute algunos modelos y teorías sobre el comportamiento informacional que deberían ser considerados en los debates sobre políticas de información, y plantea un modelo de “Campo Informacional” con temáticas que pueden guiar su construcción.

In the information age, the discourse surrounding the citizen's need to have access to data has become common. But the problem of “access” is only the tip of the iceberg. The challenge includes empirical evaluation of the informational flows in the population and their effects and the identification of problems that affect democratization of access. Since the decade of the 1990s, many information policies have been designed in Brazil and Latin America and, even when the reductionist tendency of these proposals has been giving way, their design is still performed without heed to advances in information science in the following three aspects:

- 1.

Policies persist in a system-centered approach, to the detriment of the user;

- 2.

Policies disregard the latest models and theories on human informational behavior; and

- 3.

They remain tied to a rational-reductionist outlook bereft of the ecological-contextual vision.

On the basis of problems reported in public information systems and as exemplified in the case of the Brazilian health information system datasus, this paper discusses several models and theories of informational behavior and their relationship to information policy development. The standards that gave rise to datasus and weaknesses identified in empirical studies of these standards are described. The paper concludes with a proposal for a conceptual map of the “informational field” that affects the information policies informing the datasus case in order to nurture the debate and improve the operation of policies of this kind.

TRANSPARENCY, OPEN DATA AND DATASUSInformation policies are underpinned by open access to and transparency of data.1 Transparency marks the governance style that redistributes the coordination of resources and competencies among the public and private institutional organization levels, while abandoning the state monopoly model and seeking pluralism in public functions.2 Informatics technologies can broaden access to data and intensify the demand for information and transparency of the state, thereby producing new forms of interaction between the state and the citizen.3 Access to governmental data is a requirement if citizens are to participate in political processes and public management that make democracy possible.4 The internet allows one to learn the needs of citizens with some accuracy, thereby facilitating their effective, direct participation in public affairs, while increasing the value of information exponentially through open sharing.5

As will be shown further on, however, access to governmental information is partial, superficial and complex because of contextual and user variables and as a function of the volume of public data that is not handled by the existing integration and management systems.6 The quality of information access is critical if one wishes to promote the development of independent points of view and transparent interactions between the state and society, which are key to citizens’ participation.7

Moreover, the empowerment of citizens that data encourages depends on guaranteeing its effective use not only through access to the information infrastructure, but also through building the informational competencies, techniques and ethics of users.8 Otherwise, the technological empowerment reinforces the concentration of capacities and power in those minorities with the knowledge, equipment and context needed to exploit existing data sources and flows.9

The problems of informational empowerment in Brazil can be clearly seen in the health sector. To understand these problems, three areas must be examined: a) legislation and structure of the health sector; b) public policies promoting and guaranteeing access to governmental information, and c) features of the web site implemented by the state. In the following section, we will examine each of these facets.

THE CONTEXT OF THE PUBLIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS IN BRAZIL AND THE HEALTH SECTORThe Brazilian Constitution establishes the Sistema Único de Saúde (sus) (Integrated Health System) on the basis of a decentralized model. The states and municipalities enjoy autonomy in the administration of health sector actions and resources pursuant to their respective needs.10 El Fundo Nacional de Saúde (fns) (National Health Fund) is the organ in charge of management, distribution and control of health sector budgets. Citizen participation was included in the management of health pursuant to Act 8.142/90, which established community committees called Conferências de Saúde y Conselhos de Saúde) (Health Committees and Health Counsels), whose job it is to oversee the proper allocation of health resources pursuant to the provisions of decree 1.232/94.11 Allocation transfers are grouped in funding blocks that are subdivided and assigned to component actions and programs. These blocks are defined in Ordinance 204/2007 for the following areas: a) basic health services, b) complex ambulatory services and medium- or high-grade hospitalization, c) health oversight, d) pharmaceutical assistance, and e) sus management.12 Professionals serving on these counsels and in charge of these funding blocks must have legal and administrative knowledge of the field in question and they must be familiar with the public health needs of their locality. All information of this structure resides in the so called datasus system.

In the 1988, the Braziian Constitution regulated public access to data in the following terms: “[...] todos têm direito a receber dos órgãos públicos informações de seu interesse particular, ou de interesse coletivo ou geral, que serão prestadas no prazo da lei, sob a pena de responsabilidade, ressalvadas aquelas cujo sigilo seja imprescindível à segurança da sociedade e do Estado”.13

This same document mandated the creation of mechanisms for consulting information: “Cabem à administração pública, na forma da lei, a gestão da documentação governamental e as providências para franquear sua consulta a quantos dela necessitem”.14

In 2011 the Information Access Act (12.527) was promulgated. This act added new duties with regard to public information access to governmental documents and confidentiality. Public and private organization are subject to the terms of this Act, which modified the previous legal ordinance by changing “confidentiality” of government documents from a general feature to a specific exception.15 The use data networks to share documents became compulsory: “Para cumprimento do disposto no caput, os órgãos e entidades públicas deverão utilizar todos os meios e instrumentos legítimos de que dispuserem, sendo obrigatória a divulgação em sítios oficiais da rede mundial de computadores (internet)”.16

This year, Brazil joined the multilateral Open Government Partnership, taking on the obligation to make efforts to provide transparency and ensure access to information. The Open Government Partnership establishes targets that are periodically evaluated by independent committees,17 even as Brazil had in 2009 already established digital inclusion policies through presidential decree 6.991, de 2009, known as the National Digital Inclusion Plan.18

DATASUS, ITS PROBLEMS AND THE CONCEPT OF INFORMATION FIELDdatasus is an informatics system that compiles and makes available the information of the Integrated Health System (sus), including information regarding its administrative actions and federal government funding through the Ministry of Health. These resources are allocated pursuant to Article 2 of Act 8.142 (1990) to cover expenditures of the Ministry of Health, its agencies and administrative agencies, and are also allocated to the federated states and municipalities in the country. Its portal is known as datasus. datasus has gradually become more visible in accord with the growing demand for information; however, the relations between the system and the user did not improve.

In 2013, Rita Cassiano of the Universidad Estadual Paulista UNESP performed a study of professional nursing users in the City of Assis, Brazil, São Paulo, Brazil19 in which she measured user degree of mastery of DATASUS. The results were worrisome. These users, consisting of health sector workers and students, were unable for a variety of reasons to take advantage of the available data structure. The reasons behind these failures included difficulties with menus, broken hyperlinks, unfamiliarity with data display mechanism and unawareness of the administrative structure.

What is worrying is that this situation is not unique to Brazil: it is quite common around the world.20 About one third to half of all online time is wasted on useless queries and interactions with information systems.21 It has been estimated that fully half of all internet users in the United States of America feel dissatisfied with the degree of usefulness and granularity of information provided in government websites. They also are frustrated with the time investment required to extract such information that is exacerbated by the opaque terminology used, the unfamiliar thematic organization and deficient metadata support devices.22

Other reported sources of user frustration with government websites include unpredictability of interfaces,23 slow upload and download speed,24 display deficiencies, unintelligible content and the dearth of user support.25 The situation is exacerbated, when we understand that these are merely the “hard” elements of information systems,26 the visible portion of a larger problem. Underlying these issues are the socio-technical properties of the system that Checkland called the “soft” matter that configure the “information field”,27 The information field is a transparent, historical, contextual, individual and collective technological and sociological informational structure that is crisscrossed by conflicting and cooperating forces acting in accord with the laws of field theory.28

The information field can be understood from the following five perspectives:

- a)

As a technical, technological architecture that includes micro-power, oversight and control structures that guide retrieval of information and monitor users within the standardization field of action, acting as a digital panopticon.29

- b)

As a semiotic, ideological and cultural structure of isotopies that shift and imbed representations and routines from one society to another.30 Their main transmission medium is classificatory nomenclatures.31

- c)

As a field of conflict and cooperation among informational agents in terms of symbolic negotiation32 and negotiation of meaning.33

- d)

As a field of action for informational behavior of users and the formulators of the system.

- e)

As an epistemological, historical, cultural and ideologically conceived object that is studied and explained from the standpoint of common sense, science and technology.34

These approaches, which comprise more than 50 years of social science research seeking to provide an accurate understanding of informational phenomena, should be considered by those in charge of designing information policy if they wish to enjoy greater efficiency in the development of associated policies. The conceptualization of public information policies is still wanting for interdisciplinary approaches and a more complex vision. These deficiencies, therefore, turn up in critical information systems such as datasus.

INFORMATION SCIENCE AS DRIVER OF PUBLIC INFORMATION POLICY MANAGEMENTWhy are informational phenomena ignored in the field of public information policy management? Why do we continue to see cases such as DATASUS in the sphere of regional public information? Latin American political science moves along a road in which deterministic and complex outlooks coexist,35 but in practice formalist processes take over that squash any kind of dialectic or participative approach. There is an authoritarian, institutionalized tradition at the foundation of political action systems, which O’Donnell called the “authoritarian bureaucratic state”.36

All analyses of the formulation of informational policy are conditioned by context, public deliberation and construction of discourses.37 These factors are affected by the tendency to oversimplify and, as such, they contribute to the loss of essential elements that public policy determines.38 This is why the interdisciplinary approach of information science (IS) can serve to drive the formulation of public information policies.

To begin this approach between IS and information policies, we provide a series of reflections arising from application of Moore's information policy analysis matrix,39 in the dimensions of “human resources” and “information policy markets” as these are posited by Sebastián and Rodríguez.40 The following two questions shall serve as guideposts for this discussion:

- 1)

The legitimation and adjustment of internet-based informational architectures; and

- 2)

The construction of “empathy” between informational structures and the needs, feelings and abilities of users.

In this discussion, the state plays the role of protagonist in term of symbolic negotiation and violence41 (negotiation of social representations and their imposition by decree or cooptation). As such, their agents must have clear, broad-based ideas regarding the costs of adjustment and implementation of new informational routines and the symbolic deconstruction of the informational market that this supposes. To these ends, the theories discussed herein contribute central concepts.

THE CONTEXT AND THE USER ARE CRITICALIt took IS 40 years to recognize the importance of the context in which information systems reside. Similar to the case of informatics science, IS was born during the fall of European powers and the rise of the United States of America and Soviet Russia, in a period marked by reformulation of the scientific, industrial and capitalistic project. Initially, both of these sciences were practical, hermeneutically oriented approaches with only slight critical impetus,42 marked by a monolithic vision inherited from Euro-centric thought of Paul Otlet.43 Considerations of the “user” or context other than those with a European profile were non-existent. By the end of the twentieth century, with the popularization of informatics, the question of citizens making use of information, i.e., the user public, began to draw more attention.44 Later on, in 1976, Brenda Dervin criticized the assumption regarding the needs of users posited by so-called “experts”.45 Twenty years later, the social constructionist epistemology came entered the scene of IS46 through which the role of context was afforded greater importance.47 This approach, moreover, offered ecological and evolutionary insights to the disciplinary field of IS.48

This series of developments applied to the design of information policies entails serious historical, geographic and cultural consideration of the target population and the application of an interdisciplinary hermeneutics in order to specify the niches and profiles of users who are subject to the proposed informational governance.

INFORMATIONAL BEHAVIOR OF USERS AND FORMULATORSThe roles of the user and the formulator of information systems are not fixed. These roles change and alternate as the activity of the subject and context change. What remains fixed is the egocentrism of the implicated subjects. The informational policies and systems are formulated on the basis of group assumptions and interests. From the standpoint of the user and despite its best of intentions, an information system is a sort of invasive force. An efficient symbolic negotiation is required in order to achieve real, lasting effects. Moreover, the self-organization processes gradually emerging from users must be monitored. These emerging elements are intricate and unforeseen. As such, they must be considered in the strategic vision that presupposes complexity and chaos.49 The central problem resides in the meaning of actions and the structures for the participating agents.50

The relationship between policy designers and users is not an empty space, but rather a table on which diverse interest groups may cooperate and conflict as they play their cards, whether openly or covertly. Each of these factions struggles to increase the freedom of its discretionary freedom until such time as thee are checked by the power of the institutional context.51 In such matters, the main problem is that of information asymmetry and the construction of self-regulation and sustainable means for balancing them out.

RATIONALITY, THE MEANING OF INFORMATION, “INFORMAVORES” AND HIVE MENTALITYOne cannot assume the informational behavior is rational. This is something already addressed in in limited rationality theory.52 Thanks to Brenda Dervin, we know that a) giving more information is not necessarily better; b) information is not consumed out of context; c) formal information channels are not always the best; and d) the multiple functions of information are not simple, specific or pragmatic. The purpose of information is to make meaning and to conceptualize. To know is more of a verb than a noun: it is diversity and complexity. Informational behavior, understood as everyday human action mediated by language, is a social construction erected through negotiation of meaning. The design of public policy must take into account the reality of the user, supported by the concept of social fabric.53 It is important to understand the information flows in the community logic from the standpoint of “small worlds”54 and their social gratification structures.55 Information policies must be designed with a bottom-up vision, that is, from the community upward and not from the standpoint of technology, technological trends or the world-view of the formulators. The process must include consultation with users and interest groups, while providing room for negotiation to make permanent corrections.

Nurtured by information, human beings may be seen as informavores,56 that constantly attempt to flee from cognitive dissonance and doubt. The data hunter needs to build meaning at the least cost in terms of energy investment. As such, credibility beats out accuracy, convenience outdoes veracity and consonance trumps dissonance. An informational architecture is not accepted as much for its technical excellence as for the meaning it conveys to the user in terms of economy of effort. Even though we inhabit a grapho-centric world,57 the formal written channels are not necessarily those most widely used. When information is seasoned with ludic elements, it no doubt enjoys greater acceptance.58

Human being move in swarms,59 informational chain structures that unconsciously drive coordinated collective action, while mobilizing primal mechanisms based on the emotional underpinnings of the herd.60 This feature of human behavior cannot be left out of the design of information policies.

ASYMMETRIES OF INFORMATION, ENERGY REQUIREMENTS AND OPPORTUNISMRonald Coase saw that all economic transactions are informational and entail the costs of searching, negotiation and preservation.61 The transaction is an information exchange structure that stipulates requited payments to be made in the future for the property, asset or service that is enforceable through express stipulations to fulfill respective duties. We would never attempt to access all information because search costs are prohibitive. Acting with limited information, we prefer data that is easy to access regardless of its quality. We exchange information with agents who are unfamiliar and also less than ideal. We prefer simplified negotiations to more complex ones that might be more favorable to our interest. This information gathering behavior of minimum effort has been observed in the field of linguistics62, library science63 and information science.64

The transaction cost and the tendency to exert the minimum effort are sources of informational asymmetry. Those agents with energy/economic capacity are able to gain access to more and better information, thereby reaping advantages. Members of government, organizational representatives and knowledge workers are examples of groups that are capable of affording the high costs of information, while also clearing technical and competency barriers. This concentration of power will tend to institutionalize, with the inference that it is the proper order things. Once this situation is deemed natural, the dominant interest groups will have reasons to reject technological or policy changes that cast doubt upon their dominance and otherwise put their information capital at risk. All policies will simultaneously have to offer, market and impose their proposals to change the state of things.

This asymmetrical situation is intersected by what Williamson defined as “opportunism,” which is the tendency to economically exploit counterparties in transactions without regard to the damage that might be done.65 Opportunism is the basis of the agent-principal dilemma in agency theory.66 A social actor called the “principal” (which may be a person or a collective) chooses and formally designates an “agent” to act on his behalf. Once duly empowered, the agent manipulates the information flows he receives in the name of the principal for the purpose of increasing his power and influence. Elected public officials and bureaucrats representing citizens are affected by the institutional agency phenomenon. As such, their handling of information policy will be influenced by minority interests and maneuvers that tend to support the information monopoly they wield.67 All information policy will bring changes in the statutory agency relationships existing between government, citizens and the state; and will tend to create uncertainty and opposition among government political groups, which often indulge in covert boycotts of each other's policies and positions. The behaviors of government officials should also be monitored and subject to ongoing adjustment. All policy is a process of ongoing learning and accommodation.

Since information is limited, expensive to secure and subject to opportunism, that portion of information especially valued for being optimal or strategic will be retained by powerful interest groups. Using the Akerlof lemon theorem,68 we can fairly deduce that monopolization of the best information and the citizen's incapacity to differentiate good information from bad would cause growth in the use of the latter. These reflections bring us to the question: Just what constitutes “good information?”

This problem is one of “relevance of information,” something Saracevic considered key,69 concluding that we have not invested enough resources to research this problem, even when globalization and popularization of informatics media have become a public problem. With the privatization of search and retrieval media, the problem of relevance was also privatized, and studies on relevance have offered scant improvements to information systems.

In conclusion, the understanding of information in terms of transactional costs within an asymmetrical context and in light of agency, opportunism and monopoly is a prerequisite of designing realistic policies. Research on the concept of relevance embodied in each policy, user and circumstance is also needed; unfortunately, this area of research has been shirked and left to flounder by the large information corporations.

INFORMATIONAL COMPETENCIES AND EMPOWERMENT OF THE CITIZENThe concept of I-literacy, or international literacy (alfin), also contributes to the study of information policy. The development of informational competencies requires literacy in informatics technology, and in reading and writing; but these are necessary conditions not sufficient condition of alfin. Two additional levels are required: the meta-analytical level, or the capacity to assess and duplicate sources; and the critical ability underpinning comprehension of discourse and the ability to propose alternatives. It is an analytic, synthetic, shared information processing chain for debate and generation of new proposals.70 The final level consists of what Capurro calls “responsible moral action”,71 a kind of informed, foundational action that demands ongoing communication and critical dialogue with other agents for the purpose of securing data, joint reflection and retaining flexibility in the opinions held.

Creating informational competencies is difficult and expensive to manage because it entails profound changes in terms of education and empowerment. It requires ensuring basic rights, such as the right to education and free expression. It means thinking in broad terms about variables that are apparently far removed from matters of information policy, but which can nonetheless determine their success or failure.

CONCLUSIONSThe countries lying on the so-called “periphery” were late to the digital information game. Because of their lack of experience and human capital they ended up reinforcing their traditional dependence on Europe and North America, importing the policies in vogue without reflection or genuine knowledge of cause. These policies tend to clash with the typical features of the informational order of developing countries, a reality that has been neglected in terms of research and is as yet largely unknown. Information policies in Latin America have been posited in a context of problems, restrictions, inequality and authoritarianism.

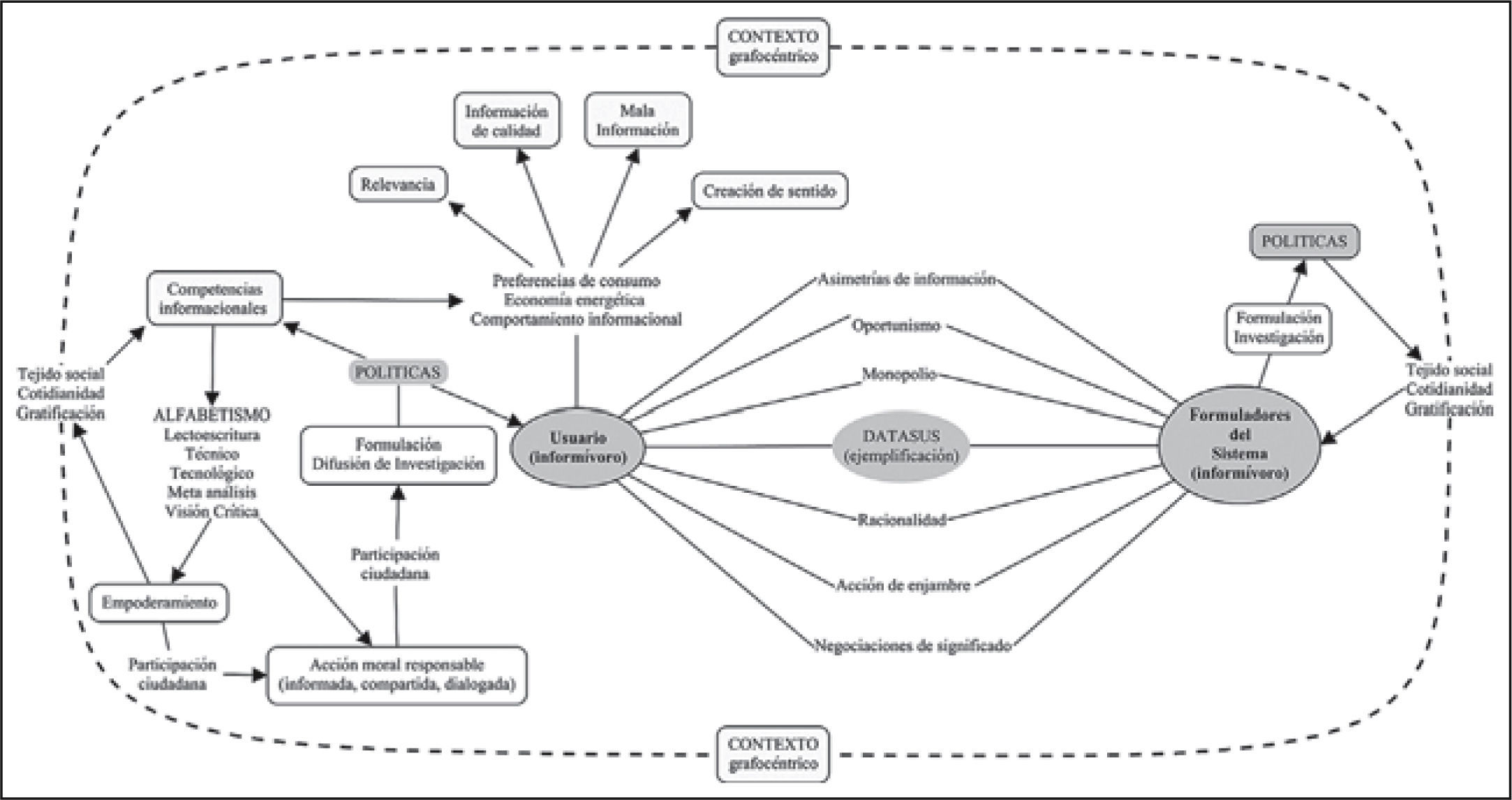

A distinct approach is urgently needed, one that can be built on the foundation of social science and research in IS describing human informational behavior. This paper compiles several of these theories to serve as lenses to examine datasus. This exercise is presented in Figure 1. This exercise allowed us to develop a drawing of the “informational field” of health in Brazil, whose center is datasus. This summative, but not simplified, picture allows us to articulate multiple phenomena and lines of research that could provide an empirical-theoretical foundation for information policy makers.

Diagram of the “information field” structured by factors that affect the development of information policy, exemplified using the Brazilian health information system datasus. Each node corresponds to the different theoretical concepts developed in this paper and is a research area to be explored. Source: By author.

Each theoretical area addressed in this paper generates research questions, such as the following:

- •

Context: What is the context of the users of datasus? Are they largely urban dwellers? Are they in small cities? What is the history of datasus and who are its stakeholders? What interests and conflicts align with these stakeholders?

- •

Meaning: How do the diverse users and stakeholders perceive, represent and associate with the datasus system? Are these representations associated with other social or cultural processes and features? What is the definition and level of relevance of the system and its contents from the standpoint of the users and the stakeholders?

- •

What is the system's degree of “intuitiveness”? What are its ludic and gratification elements? What is the system's rationale and that of the user? Is there room for “symbolic negotiation” with users?

- •

Asymmetries: Who are the system actors that can be subject to the phenomena of agency, opportunism and information monopoly; and what asymmetries can they produce? How can these inequalities be counteracted in a sustainable, self-regulating way?

- •

Effort: What is the degree of usability of the system in terms of energy investment? What is the degree of complexity of contents and data representation?

- •

alfin: What is alfin level of the users in diverse fields that converge in the system (legal, medicine, bureaucracy, etc.)? Is the system aligned with the competencies of the target users?

- •

Control: What kinds of “swarm” phenomena can be triggered in the system? What kinds of consequences can these phenomena produce? How can detrimental consequences be anticipated and controlled?

These discussion areas can be used in a complete review exercise or evaluation of any public information policy project. The usefulness of this kind of questioning and thought structures resides in the attempt to preserve the complexity implied in the development of policies, while maintaining an organized, systematic approach based on consistent theoretical models. This exercise also encourages previously unexplored perspectives, such as those associated with problems of power, agency, information monopoly and opportunism, and the principle of least effort.

The dream of a public network of open and free data, and the nightmare of oversight, control, electronic colonization, and other forms of power concentration, coexist in the project of the information society. The dominant actors hope to perpetuate information asymmetries that provided them advantage. Only a state policy designed with an awareness of these conflicts will be able to bring control and balance to the field. Policy makers, however, often end up acting through authoritarian schemes that fail to question the local reality, while never endeavoring to make room for negotiation with users. They are content merely to mimic imported perspectives and impose these approaches through the force of law, accompanied by hefty doses of demagoguery. The investment of resources favors things rather than persons. Without research or technically or ethically literate users, technological progress will continue to foster ever greater informational asymmetry. In this way, the people will be more malleable and the already feeble state of the institutional order will be further eroded; while normative efforts will be largely cosmetic leaving the underlying state of things untouched.

R. C. G. Sant’ana, Tecnologia e gestão pública municipal : mensuração da interação com a sociedade.

A. M. B. Malin, “Gestão da informação governamental: em direção a uma metodologia de avaliação”.

V. Ndou, “E-government for developing countries: opportunities and challenges”; R. C. G. Sant’ana, Mensuração da disponibilização de informações e do nível de interação dos ambientes informacionais digitais da administração municipal com a sociedade.

K. Frey et al., O acesso à informação. Caminhos da transparéncia: análise dos componentes de um sistema nacional de integridade.

Opengovdata, 8 Principles of Open Government Data.

J. Manyika et al., Big data: The next frontier for innovation, competition, and productivity.

R. C. G. Sant’ana y F. Rodrigues de Assis, “Acessando dados para visualização de afinidades nas votações entre parlamentares do Senado”.

C. Berrío-Zapata, “Entre la Alfabetización Informacional y la Brecha Digital: reflexiones para una reconceptualización de los fenómenos de exclusión digital”. [Between informational literacy and the digital divide: reflections toward a reconceptualization of digital exclusion phenomena]

M. B. Gurstein, “Open data: Empowering the empowered or effective data use for everyone?”; P. Norris, Digital divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the Internet worldwide.

R. F. d. Brasil, Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil.

R. F. d. Brasil, Lei N° 8.142 de 28 de Dezembro de 1990. Dispõe sobre a participação da comunidade na gestão do Sistema Único de Saúde (sus) e sobre as transferências intergovernamentais de recursos financeiros na área da saúde e dá outras providências; Decreto N° 1.232, de 30 de Agosto de 1994. Dispõe sobre as condições e a forma de repasse regular e automático de recursos do Fundo Nacional de Saúde para os fundos de saúde estaduais, municipais e do Distrito Federal, e dá outras providências

R. F. d. Brasil, Portaria N° 204 /gm de 29 de janeiro de 2007. Regulamenta o financiamento e a transferência dos recursos federais para as ações e os serviços de saúde, na forma de blocos de financiamento, com o respectivo monitoramento e controle.

Artículo 5o., inciso 33 de la Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil.

Idem.

R. F. d. Brasil, Lei n° 12.527 de 18 de novembro de 2011. Regula o acesso a informações previsto no inciso xxxiii do art. 5o, no inciso II do § 3o do art. 37 e no § 2o do art. 216 da Constituição Federal; altera a Lei no 8.112, de 11 de dezembro de 1990; revoga a Lei no 11.111, de 5 de maio de 2005, e dispositivos da Lei no 8.159, de 8 de janeiro de 1991; e dá outras providências.

Capítulo ii, artículo 8o. de la Lei n° 12.527 de 18 de novembro de 2011.

O. G. Partnership. Open Government Partnership Declaration.

R. F. d. Brasil, Decreto 6.991 de 27 de outoubro de 2009. Institui o Programa Nacional de Apoio à Inclusão Digital nas Comunidades - Telecentros.BR, no âmbito da política de inclusão digital do Governo Federal, e dá outras providências.

R. d. C. Cassiano Lopes, Percepção dos usuários sobre o processo de acesso a dados da saúde em sítios do Governo Federal.

V. S. Oliveira, Buscando interoperabilidade entre diferentes bases de dados: o caso da biblioteca do Instituto Fernandes Figueira;E. M. F. Barboza y E. M. d. A. Nunes, “A inteligibilidade dos websites governamentais brasileiros eo acesso para usuários com baixo nível de escolaridade”.

J. Lazar et al., “Help! I’m lost: User frustration in web navigation”.

K. Bessiere et al.Understanding Computer user frustration: Measuring and Modeling the disruption from poor designs.

B. Shneiderman, “Designing information-abundant web sites: issues and recommendations”; DesigningThe User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction, 4/e (New Edition).

J. Ramsay et al. “A psychological investigation of long retrieval times on the World Wide Web.”

Bessiere et al., Understanding Computer user frustration…

P. Checkland, “Systems thinking.”

Berrío-Zapata, “Una visión crítica de la intervención en Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicación (tic) para atacar la brecha digital y generar desarrollo sostenible en comunidades carenciadas en Colombia: el proyecto Cumaribo.” [A critical vision of interventions in information and communication technologies in order to attack the digital divide and generate sustainable development in marginalized communities in Colombia: the Cumaribo project]

K. Lewin, La teoría del campo en la ciencia social. [Field theory in social science]

S. Zuboff, “Be the friction: Our Response to the New Lords of the Rings.”

I. Blikstein, Kaspar Hauser ou a fabricação da realidade;C. Avgerou, “Information systems in developing countries: a critical research review.”

H. A. Olson, The power to name: locating the limits of subject representation in libraries.

In the informatics field, Kiingas defines symbolic negotiation as a process by which the parties try to reach agreements on the intellective media to serve their purposes through the application of symbolic reasoning techniques. This is a definition leaning toward mathematical logic including socio-cultural elements. P. Kiingas and M. Matskin. “Partial deduction for linear logic: the symbolic negotiation perspective”.

For Bouquet, meaning negotiation is any kind of viable approach to semantic interoperability between autonomous entities, who cannot evaluate semantic problems by “by looking inside the head of the other.” As such, they accept a social process of negotiation and convention regarding the meaning (semantics) and the intention of the speaker (pragmatics) in the communication process. Burato defines them simply as the general process by which the agents come to agreement about the meanings of a subset of terms. P. Bouquet and M. Warglien. Meaning negotiation: an invitation;E. Burato et al. “Meaning Negotiation as Inference.”

K. Tuominen et al. “Information Literacy as a Sociotechnical Practice.”

G. Flexor y S. P. Leite. “Análise de políticas públicas: breves considerações teórico-metodológicas.”

G. A. O’Donnell, Modernization and bureaucratic-authoritarianism: Studies in South American politics; “Reflections on the patterns of change in the bureaucratic-authoritarian state.”; Catacumbas.

S. H. Linder y B. G. Peters. “A metatheoric analysis of policy design.”

Flexor y Leite, “Análise de políticas públicas…”.

N. Moore, Information policy and strategic development: a framework for the analysis of policy objectives.

M. C. Sebastián et al. “La necesidad de políticas de información ante la nueva sociedad globalizada.”

P. Bourdieu, “Structures, habitus, power: Basis for a theory of symbolic power”; M. N. Gonzalez de Gomez, “Novos cenários políticos para a informação”; Bourdieu, “La fabrique de l’habitus économique”; C. A. Tamayo Gómez et al. “Génesis del campo de Internet en Colombia: elaboración estatal de las relaciones informacionales”. [“Genesis of the internet field in Colombia: state implementation of informational elations”]

L. J. McCrank, Historical information science: An emerging unidiscipline.

I. Rieusset-Lemarié, “P. Otlet's mundaneum and the international perspective in the history of documentation and information science.”

B. M. Wildemuth y D. O. Case. “Early information behavior research.”

B. Dervin, “Strategies for dealing with human information needs: Information or communication?”

K. Tuominen y H. Savolainen. A Social Constructionist Approach to the Study of Information Use as Discursive Action; Tuominen et al., “Information Literacy…”.

C. Courtright, “Context in information behavior research.”

A. Spink y J. Currier. “Emerging Evolutionary Approach to Human Information Behavior”.

K. M. Eisenhardt y S. L. Brown. “Competing on the edge: strategy as structured chaos.”

Dervin, “Sense-making theory and practice: an overview of user interests in knowledge seeking and use.”

M. Crozier, La sociedad bloqueada;P. Medellín Torres, La política de las políticas públicas: propuesta teórica y metodológica para el estudio de las políticas públicas en países de frágil institucionalidad. [The blocked society: P. Medellín Torres, The politics of public policy: theoretical proposal for the study of public policies in country with fragile institutions.]

H. A. Simon, Models of bounded rationality.

Tuominen y Savolainen. A Social Constructionist Approach…

Concepto de Efreda Chatman que refiere al poder que un grupo social pequeño y cerrado ejerce sobre la actividad informacional de sus miembros.

E. A. Chatman, “Life in a small world: Applicability of gratification theory to information-seeking behavior.”; “The impoverished life-world of outsiders.”

G. A. Miller, “Informavores”.

H. M. Serres, Hominescências: O começo de uma outra humanidade.

W. Stephenson, The play theory of mass communication.

S. Gutiérrez et al. “Swarm Intelligence Applications for the Internet.”

D. Nahl, “The Centrality of the Afective in Information Behavior”.

R. Coase, The firm, the market and the law.

G. K. Zipf, Human behavior and the principle of least effort: an introduction to human ecology.

Z. Liu y Z. Y. L. Yang. “Factors influencing distance-education graduate students’ use of information sources: A user study.”

C. N. Mooers, “Mooers’ Law or Why Some Retrieval Systems Are Used and Others Are Not.”; L. A. Adamic y B. A. Huberman. “Zip's law and the Internet.”

O. Williamson y S. E. Masten, The economics of transaction costs.

S. A. Ross, “The economic theory of agency: The principal's problem”; B. Mitnick, “Origin of the theory of agency: an account by one of the theory's originators”.

Eisenhardt, “Agency theory: An assessment and review”.

G. A. Akerlof, “The market for” lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism”.

Saracevic, T. “The concept of “relevance” in information science: A historical review”; “Relevance: A review of and a framework for the thinking on the notion in information science.”; “Relevance: A review of the literature and a framework for thinking on the notion in information science. Part III: Behavior and effects of relevance”.

Berrío-Zapata, “Entre la Alfabetización Informacional…”. [“Between Informational Literacy…”]

R. Capurro, “Información y acción moral en el contexto de las nuevas tecnologías”. [“Information and moral action in the context of new technologies.”]