The study offers a historical analysis of the liberal library system in Spain during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, while describing the library holdings, the diverse functions of provincial libraries and their usefulness to society. Finally, we outline the typology of the library that arose from policies hampered by various inherent shortcomings. We conclude that the resources available were insufficient to achieve stated objectives, resulting in deployment of centers that resembled depositories of cultural heritage, rather than places for reading.

Se presenta un análisis histórico del sistema bibliotecario liberal en España durante el segundo tercio del siglo xix. Se estudian las características del fondo bibliográfico, las distintas funciones de las bibliotecas provinciales y la utilidad que tenían estos centros en la sociedad; finalmente se esboza una tipología bibliotecaria que fue el resultado de la política que realmente se llevó a cabo, lastrada por las distintas carencias inherentes a los problemas asociados a la misma. Se concluye que los medios disponibles no eran los adecuados para conseguir los objetivos inicialmente planteados, por lo que los centros creados no se ajustaban por completo a las funciones que se habían previsto sirviendo como depósitos del patrimonio cultural más que como centros activos de lectura.

This paper aims to identify the main functions of the public library within the window of the study, while pointing out the main features of the bibliographic collection that should exist in provincial libraries and highlighting the existing incongruences in the Spanish model library.

This study employs a methodology consisting of identifying the sources that will allow development of the proposed objectives on the basis of the knowledge that authors had of them derived from previous research on recent historical periods and locating the pertinent documentation in diverse archives. Through an analysis of the correspondence existing between the diverse organs, in accord with the provincial administration divisions put in place with the establishment of the national liberal political system, said documentation, original and unpublished, reflects the operation of the Spanish administration in the study window.

Most of the information has been gathered from the Historical Archives of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando (arabasf) located in Madrid, because the academy was responsible for implementing the country's heritage protection policy in the second half of the nineteenth century. As such, the relevant documentation is currently held there, even though it is not strictly an organism of the the Central Administration. We also gathered information from the Historical Archives of the National Library of Spain (abn) and the General Archive of the Spanish Central Administration (aga), the latter located in the town of Alcala de Henares.

The national library system was born during a period when the State, wishing to preserve the cultural and literary assets of religious communities suppressed in the 1830s, was forced to develop a nationalization policy to protect bibliographic collections of the orders of the regular clergy. A such, we are interested in understanding the process of the founding of the system of provincial public libraries, the collections existing at the time and the kind of funding this enterprise enjoyed. Moreover, we wish to learn about the extent to which the needs of the society at that historical moment were being met, in view of the funds available, and to develop an effective library policy. As warranted, we will also identify problems or deficiencies that impeded development of these policies and attainment of objectives.

THE HONORARY ADMINISTRATION AS MANAGER OF CULTURAL POLICY. THE PROCESS OF GATHERING AND CATALOGING LIBRARY DISENTAILEDThe royal decree of July 25, 1835 (Gaceta de Madrid, no. 211, July 29, 1835), cancelled the exception enjoyed by those monasteries and convents with less than twelve members to retain property, such property, including “[...] archives, libraries, paintings and other goods that may be useful to science institutes and arts [...]” were confiscated by the state: although it was not until the royal decree of March 9, 1836 (Gazette Madrid, no. 444, March 10, 1836), that the final disposal of to these objects was proposed and we find the first mention of provincial libraries.

By royal order of July 29, 1835 (arabasf, leg 55-2 / 2) civilian committees were created tasked with performing inventories of literary and artistic property. Once these inventories were taken, the properties were to be moved to the provincial capital for storage in “comfortable and safe sites” to await final disposition. The problem was that no funding was provided to ship these assets, and those working these commission were expected to work out of a sense of “[...] pure patriotism and love of the arts.”

Attempting to address this situation, royal decree of May 27, 1837 (Gaceta de Madrid, no. 907, May 28, 1837), created the scientific and artistic commissions, which was the result of the observations of various political leaders regarding “[...] obstacles to full compliance [...] “of the previous legislation. The most significant departure in this decree was the provision allowing the sale at public auction of the works not considered valuable enough to be preserved in order to raise funds to take inventories, ship objects and create libraries.

The difficulties faced, however were numerous. In order to facilitate the creation of these centers, royal decree of 22 of September 1838 (Gaceta de Madrid, no. 1407, 23 of September of 1838) allowed provincial universities to assume the functions of these commissions and create libraries in accord with the Valencia model (Muñoz Feliu, 2006). Despite these measures, very little changed on the ground, according to the survey of July 1842 (Gaceta de Madrid, no. 2834, 14 of July 1842; García López, 2003: 133-157).

Finally, royal decree of 13 of June of 1844 (Colección…, 1847: 292-298) created the commission of historical and artistic monuments, whose aim was take action in order to “[...] contain the devastation and loss of precious objects […] with the knowledge, method and regularity that is warranted.” In a novel approach, the decree created the Central Commission to act as a central organ, but without authority or power of execution over the provinces.

Early reports from the provinces were encouraging: all of the commission seemed to be working diligently and full of purpose. The commissioners, moreover, appeared to be duly educated and apprised of the world of arts and letters. Despite this early optimism, these commissions also failed to meet objectives fully.

In light of these instances, it is clear that the task of disentailing cultural assets was not approached through a genuinely planned legal process, but rather were quite reactionary in nature, with decrees being issued in response to the sudden closure of convents and monasteries. (García López, 2003). As observed by Hernández Hernández (2002), the government's takeover of convents and monasteries was not sufficiently planned, a situation that would bring negative consequences to the sphere of art. One must keep in mind that extrinsic and intrinsic problems faced by the state, such as the lack of cooperation on the part of religious orders, the improvised approach to the closure of convents and monasteries, ongoing war, lack of political will to invest in conservation of assets, lack of logistical coordination and lack of funding would be constant obstacles in this process.1

In addition to the organizational aspects of this body charged with cultural management, in order to study the foundational bibliographic holdings of the first national library system, we must first examine certain aspects of the procurement process of these holdings. Public libraries established during the liberal stage were founded with the books belonging to the libraries of the suppressed religious communities. The first step, therefore, was to gather the books from the buildings that were formerly convents and monasteries. To do this, inventories were needed of the bibliographic holdings and other valuable cultural assets not previously sold off.

The provisions issued in order to carry out these tasks, however, were flawed from the start, in that it was not possible to seat a commission of suitably competent members to perform the inventories or appraise the works to be preserved and determine what could be sold off in every provincial convent and monastery throughout the country. Because of this this lack of planning, the result was predictable: the commissioners of the Tax Ministry (Hacienda) were mostly involved in gathering legal documentation needed for transfer of ownership, meaning their management of the disentailment of libraries, and other artistic assets was rather expedient and without depth.2

Moreover, the descriptions of the collections contained in the original inventories were woefully inadequate. This circumstance was exacerbated by the time lapse of up to ten years between the confiscation of the church properties and the actual shipment of the books, during which time the care of these books was sadly neglected. In these circumstances, it was very difficult to ascertain if a given collection were complete or to track down any tomes that might have been removed.

The elements required to produce inventories were: qualified personnel, time, a workspace and economic resources. The problem was to gather all the items together. Qualified staff soon tired of working without pay, and they gradually abandoned their activities. For the books, time was running out because of poor storage conditions. Securing rent-free storage and work sites not in need of improvements or additional authorizations was not easy, as many commissions had no operating budgets. If they had had funds, the three aforementioned impediments probably could have been overcome. Lack of funding, then, would drag down the development of all these efforts.

The sale of expendable objects in situ to raise funds for establishing the library was a good idea, but once put in practice it caused more problems than benefits. Many books were sold off without proper appraisals, likely out of ignorance and the wish to discharge unremunerated commission duties as soon as possible. Moreover, even when sales were closed and monies secured, these funds were often frittered away, while commissions, including the central commission, insisted on compliance with established standards.3 In order to standardize indexes, the central commission established the model of minimum indexing fields for provincial the commissions to fill in, insisting they follow it to the letter. Many provincial commissions, however, found this model index too time consuming and they often failed to comply with it.

Additionally, many more problem occurred when collections were to be picked up and shipped to the provincial capitals, where the libraries were to be established. While many collections were gathered and shipped from the suppressed monasteries and convents, many more were never picked up at all.4 These collections were lost to pillaging by the monks who had been turned out, by persons working in the disentailing process and other persons somehow having gained access to them. Furthermore, many valuable items that should have been preserved were legally or illegally sold off, whether through ignorance or in knowing acts of malfeasance. The Carlist War also took a toll, destroying many works, and this was exacerbated by the inaction, inertia and general ignorance of provincial authorities in conjunction with the general impotence of these honorary commissions.

THE IDEA OF THE PUBLIC LIBRARY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURYOne of the most important aspects to keep in mind when examining the public libraries created in the nineteenth century is that the concept of the public library has undergone significant change since those times.5 As such, current ideas in this regard are not valid in this study. According to García López (2007: 12), the concept of the library has had distinct meanings throughout history:

More than anything else, it was about breaking the legal barriers which by “law” or by conferring exclusive “rights” reserved library access to only a select community. That is, to make the library “public” under the law, even as the public library was still in fact inaccessible to the illiterate farmer who, moreover, had little use for it. In this sense, the public library was open to only a minority consisting of the elite learned and the studious scientist.

A determining factor in the public libraries that were created in this period is the source of the collections. Except for a very low portion of purchased acquisitions, donations or materials on legal deposit, the books came from the suppressed convents and monasteries. This means that the collections were largely religious works, many of them written in Latin. These collections ran far afield of the cultural level and interests of the majority of the mid-nineteenth century Spanish population. The lack of any real social demand for this kind of collection is one of the main reasons the liberal library system failed.6

Moreover, Spanish society did not view the public library as an institution for leisure or instruction through reading, since reading was most often a collective activity done aloud in the home.7 New reading habits become more widespread throughout the century with the rising literacy of the population; although reading was still largely an “exceptional activity” done in reading rooms or as public reading, often involving acquisition of books second-hand (Romero Tobar, 1976). These years also saw the rise of serialized print matter,8 which served to secure income for publishers, while providing affordable, accessible reading materials for the public (Botrel, 1996a).

Illustrated, encyclopedic periodicals also experienced a boom across Europe in the mid nineteenth century. In Spain, titles such as El Laberinto, Periódico Universal, 1843; El Siglo Pintoresco, Periódico Universal, 1845; La Ilustración, Periódico Universal, 1849, or El Panorama Español, and Crónica Contemporánea, published between 1842 y 1845, addressed relevant political developments during the Carlist War. Because printing illustrations was somewhat costly, these publications were more expensive, though not prohibitively, and they soon were very popular among the better off (Ferrer, 2012).

In addition to informing the text, these images also encouraged sales of these periodicals as collectors’ items” [...] providing an easy visual representation of something that despite the wealth of dramatic details remains abstract” (Botrel, 1996a: 56).9

Another key for arriving at an understanding the prevailing concept of the public library appears in royal order of August 28, 1843 (Gaceta de Madrid, no. 3303, October 5, 1843), setting attendance schedules in the National Library and the San Isidro Library of Studies. The text of this order indicates that libraries were “[...] a place of study and consultation, and in no way reading rooms for recreation and pastimes [...].” The order also goes on to forbid lending. In the same vein, National Library head librarian Eugenio de Tapia expressed his disapproval certain uses of the library (abn, 0106/03). He believed young people reading novels, which he considered frivolous and somewhat immoral, should be barred from using libraries.10

In short, the concept of public library was very different from what it is today. Additionally, when assessing libraries founded in the decade under study, one must be aware of the problems and shortcomings faced and overcome at the time, which were determining factors in the organization of collections and development of associated library services.

FUNCTIONS ATTRIBUTED TO PUBLIC LIBRARIESAnother aspect examined in this paper are the functions of public libraries versus the type of available collections. We have analyzed documents of the time establishing the central functions of public libraries. Directives reflect the discourses held by those responsible for cultural and library policy, and intentions are expressed through actual policy. Also, one must not lose sight of the difference between the mid-nineteenth century notions of these institutions and those existing today. As indicated previously, one must consider the change produced in the mentality of potential users of public libraries regarding the usefulness of the library and its impact on their lives. On the basis of a review of the literature and analyses of the diverse cases in the Spanish provinces, we have in this way identified the following four central functions of public libraries:

- •

Depositories of cultural heritage

- •

Social control

- •

Public instruction and professional training

- •

Services to the community of teachers and students

Public libraries were conceived and built as depositories of the cultural heritage of the country, largely devoted to conservation tasks of the innumerable antique works they held and really not particularly useful to a potential user public. They were, no doubt, extremely important because of the artistic and historical objects in the collections. In the context of European development, Fernández Abad (2006: 102) points out that because these centers held antique collections, they were largely devoted to conservation and organization, turning them into “library-museums.” In line with this observation, Fernández Prado (1991) holds that the creation of libraries and museums answered the need to conserve cultural heritage, rather than the need to provide popular education.

Starting with the Central Commission, there are many examples in which the various commissions described the role of public libraries as repositories of cultural heritage, collector cultural artifacts, and organizer and safe-keeper of such historical objects for archaeological or paleographic purposes. For example, a report citing the poor performance of the Provincial Commission of Almeria, clearly indicates that the main objective of the honorary administration creating the public libraries was not only the conservation of libraries but also preserving buildings.11

The Provincial Commission of Oviedo held a similar view in its proposal to gather accurate information expediently on the remarkable Asturian-style architecture that should be preserved, citing also the need “[...] to take steps conducive to the acquisition or taking possession of manuscripts of interest in historical or paleontological pursuits, an area in which important progress has been made to date” (arabasf, leg. 50-1/2 Personal- Organization...). Thus, the Provincial Commission made it clear that its vision for libraries was not based on services to the public, but rather on the preservation of documents deemed valuable.

In his opening speech of the Provincial Library, the political chief of Baleares, called these libraries “[...] a kind of temples [...]” devoted to safeguarding human knowledge in order to keep it available to the sages of the day so they are better equipped to enlighten society at large. He called libraries monuments of knowledge and depositories of enlightenment (arabasf, sig. F7881). The same idea, albeit with a nationalistic overtone, is seen in the province of Burgos, in statement indicating that the expropriated property would give the public an idea of “[...] the glories and fond memories of Castile” (arabasf, leg. 46-7 / 2).

There was a marked tendency on the part of the educated elites to consider public libraries as a “healthy” and “dignified” option for the lower classes, which were often fond of taverns, to invest their leisure time. This paternalistic vision arose from the desire to employ the public library as a tool of social control. The vision of the public library as an instrument of social control was shared by Eugenio de Tapia (abn 0106/03), who when applying to acquire a new building for the National Library stated that this transfer provided the opportunity to “[...] reduce the bother caused to library employees by the many young, rude, demanding readers of novels.” Tapia's proposal was to retain only the works of the highest “merit and reputation” and hide the rest in a separate room, because they were “[...] frivolous and otherwise morally dubious”.12

Explaining the origin of the Library of the College of Santa Cruz in the province of Valladolid (arabasf, leg. 54-7 / 2), the political chief indicated that it was founded by Cardinal Pedro Gonzalez de Mendoza in 1492, who motivated by the contemporary constitutions established by the government for both the center and the College: “[...] felt great sorrow than many libraries never materialized as stated because of lack of funding, despite their importance to general public good of Spain, and to arts and letters [...]”. Additionally, he was motivated by “[...] the honor and authority of Valladolid and its University.”

As explained San Segundo Manuel (1996), the rising bourgeoisie tried to establish its hegemony by means of cultural control and anchoring its ideology in the medieval universities, just as the nobility had done in the past. Fernandez Prado (1991: 82) explains how by increasing its involvement in art and culture (albeit in a traditionalist and conservative way), the state “becomes the protector of a cultural forms linked to the social dominance of the aristocracy and adapted to the new structure of bourgeois consumerism.” Thus, libraries, rather than addressing a social need, were devices for social control.13

The next stage in the library's practical use to society, the public library function associated with public education and vocational training, is very close to the function of controlling the entertainment of popular sectors, steering them away from “pernicious leisure” and toward culture. The natural evolution was to leverage the investment in this center to improve training of a more prepared and skilled staff, which was necessary in the new industrial society that was unfolding.14 As indicated by Trias and Elorza (1975) for the Catalan case, the key lay in moral control and vocational training.

The bourgeoisie, however, tried to find a delicate educational balance that would allow them achieve their goals. In this sense, Ponce (1987) draws attention to the double edged sword entailed in the growing educational tasks undertaken by the emerging middle class. The need to offer more educational opportunities to the masses, helping them acquire skills needed for industrial production, was acknowledged, but it was feared that this instruction could also serve to emancipate them.

The role of the book in this training process was reinforced by changes in the publishing field, which moved from conceiving the book as a “[...] sumptuary and novel object [...]” (Fernandez, 2003: 672) to a tool for permanent consultation, reinforcing ongoing training in the new industrial context, in which progress in these fields supplied by the books became “[...] necessary in the gear box of a changing society that stood amazed by the news of progress in all spheres” (Fernandez, 2003: 672).

Among the defenders of the public library as an educational institution independent of the library-museum model, the Director of the Secondary School of Orense offered arguments for the use of the school library for training and public education (aga, Educación y Cultura, caja núm. 6.738, carpeta núm. 6.584-80).15 In Navarra (arabasf, leg. 50-4/2), upon examining the works available, the Provincial Commission charged with establishing a library concluded that the collection was unfit for public use, since they were all religious in nature. The commission stated, moreover, that there were very few works that could serve public enlightenment in the fields of arts and sciences, which were main objectives set for the libraries at that time.

Finally, one must consider the use of public libraries by the community of teachers and students. On one hand, many enjoyed easier intellectual access to the holdings of these centers; while on the other, most libraries, despite being provincial, public, would up in universities or secondary schools, which also put then in physical proximity to these groups.16 First we must consider the promotion liberal politicians afforded to education in general. According to Ruiz Berrio (1970: 13-14), education was viewed by politicians, economists, intellectuals and religious authorities as the solution to all the ills of the early nineteenth century.17

Viñao Frago (1991) points out how classroom attendance of students between six and thirteen years-old years increased very slightly from 1797, when it was 23%, up to 1831, when it touched 24%. Hernandez Diaz (1986) highlights the period of 1840-1860, when the increase in primary school enrollment increased in line with the literacy rate and the number of elementary schools, which rose from 12,719 in 1830 to 20,743 in 1855, with the number of people with reading and writing skills moving from 1,290,257 in 1841 to 3,129,921 in 1860, according to available data.

However, this author does not lose sight of the proselytizing aspect offered by the control of education,18 although, as he explains, they were unable to achieve the political objectives fully in such matters. Although the gains were widespread and numerous, because work began at a very basic level, the political objective of promoting bourgeois interests was not achieved. This objective sought to implement “[...] education and a school for everyone, but not at the same time, in the same form or degree” (Hernandez Diaz, 1986:79). As indicated by Carr (1982), it was believed that control of education, as in other areas, could be achieved through highly centralized, government oversight.

According to Ponce (1987), the so-called liberal educational reform would constitute a revolution in education. The difference between reform and revolution is that the former occurs through non-traumatic social changes, allowing changes in class dynamics without breaking down its structure. therefore, reforms are a “[...] backlash within education of an economic process by which an aristocratic and agricultural society receded against the advances of a merchant and industrial society” (Ponce, 1987: 165-166). The author calls attention, however, to two revolutions in the history of education: class division of primitive society and the replacement of feudalism by the bourgeoisie.

Regarding the role of libraries in education, Cruz Solis (2008) indicates that they were first cited as an educational resource in 1845, when Gil de Zarate said he believed a library was essential in all secondary schools, in the same way science curricula had experimental laboratories. Budgetary problems, however, prevented this idea from being developed. The influence of the education system on libraries is crucial when these are understood as part of the education and training system, as indicated by San Segundo Manuel (1996). Nonetheless, one must consider the other tasks entrusted to libraries created in the mid-nineteenth century in order to grasp their essence.19

Despite provisions to ensure public access to the library, the university library of Zaragoza, which housed books from the suppressed orders, made these available exclusively to professors and students (aga, Educación y Cultura, caja núm. 6.735, carpeta núm. 6.581-2). In Salamanca, the president tried to encourage students to consult the works from convents and monasteries, which the university held in another building.20

The same view is echoed by the Provincial Commission of Badajoz (arabasf, leg. 44-5/2), which stated that the library and the museum to be established were of vital importance, because there had never been any institutions of this kind in the province, despite a great need for such institutions in that demarcation and throughout the country to promote literature and the arts. Regarding the condition of books, the commission reported incomplete works and a collection of inadequate scope to serve the illustration of the public, adding that children would not open “even out of curiosity” books so old and battered.

As we have observed, the criteria for setting objectives varied from one province to another depending on the opinion of those in charge of the provincial commissions or their commissioners. Moreover, these objectives were not laid out in the regulatory guidelines nor did the Central Commission provide any clarity regarding the ends of the centers to be created. Thus, as in other aspects of the process, the functions of public libraries were determined by each province as the went along and without the benefit of planning, simply, rather, by adapting to new conditions as they emerged.

Government provisions, therefore, were very vague regarding the role of public libraries: regulations and provisions issued spoke of creating “centers of provincial literary and artistic wealth” or “conserving the heritage to the benefit of the public.” These expressions were so unspecific and broad that the functions of provincial centers were left to be determined by the provincial commissions. Because of the ambiguity of state guidelines, the individual provincial authorities each came up with widely disparate approaches instead of the uniformity originally desired.

FEATURES AND UTILITY OF THE NATIONALIZED BIBLIOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONAs for the disposition and use of this newly acquired bibliography from the suppressed orders, there were several possibilities. These could be the basis for an entirely separate provincial library or they could be integrated into another library based in a university, institute, secondary school, society or academy. Alternately, these could be placed in the archiepiscopal or episcopal library, or with a seminary or other religious institution. Considering the nature of the books, the latter was the most logical choice, as will be explained later.

The expropriated works were mostly religious subjects, although books on subjects such as philosophy, law or history were also quite common. However, there were very few examples of other kinds of collections, such as in the provinces of Oviedo, Segovia and Soria (arabasf, leg. 50-1/2, leg. 52-4/2, and leg. 53-4/2), which contained literary works, books on geography and exact and applied sciences, most of which were written in Latin. In Oviedo and Segovia there is evidence of acquisitions, suggesting that these works were not part of the original expropriation. The collection was totally outdated, consisting mostly of old and outdated editions of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In fact, there were very few works from the nineteenth century. All of this was further aggravated by a large number of damaged works and incomplete sets.

Whether there was any usefulness to be found in the works confiscated from convents and monasteries, therefore, was somewhat questionable. In view of the costs entailed in their preservation and treatment, which in most cases was prohibitive, these collections were more hindrance than asset. In this context, the decision was often made to donate them the libraries of religious centers, as was a case in the Baleares, Santander and Toledo (arabasf, leg. 45-1/2, leg. 7-5/2 and leg. 53-1/2).

As for the number of national heritage volumes confiscated from suppressed orders, these were not included in their entirety in the collections of the state-supported provincial libraries for the following reasons:

- •

The lack of thoroughness in the gathering process, as not all books were collected at the same time and were therefore moved to the capital gradually. On many occasions these collections were not gathered in their entirety, but they remained in the buildings of the convents and monasteries for years. On several occasions the books were not collected until the properties were sold off.

- •

The estimated number of volumes in a given depository and the actual number found through inventories varied downward and upward. This variability was more pronounced as the time between storage and inventory was more prolonged. Moreover, in many cases there were book depositories belonging to several different bodies or authorities that did not recognize such holdings in their management objectives.

- •

Books that were stolen, hidden, sold, lost or otherwise destroyed were not included in this count. Such books very likely comprised the majority of the pre-inventoried collections.

Acquisitions are added to the seized collections, but these make up only a very small percentage of holdings. Donations were a common method of growing collections, especially in school-based libraries.21 In other cases, donations had little impact because of the small size of the donation or the scant relevance of the donated works for a public school. Legal guardianship led to a similar situation: collections obtained through this system held scant interest for a public library and were hardly worth the effort required to meet legal standards to hold such books, which, moreover, often required special handling.22

Purchases were the best method of acquisition for the library, since purchases were executed in line with the library's specific needs. The endemic shortage of funds in the state treasury, however, limited allocations for such purposes. Only university based and a few provincial libraries, such as the ones in Guadalajara, Leon, (arabasf, leg. 48-3/2 and leg. 48-8/2) or Segovia (aga, Education and Culture, case No. 6,735, folder No. 6581-2; arabasf, leg 52-4/2) had money to acquire books. An annual budget for secondary school laboratories and libraries of 2,000 reales de vellón, did in fact benefit provincial libraries existing in these centers.

As for the sale of works held in public libraries done to secure financial resources, this created more problems than it solved, despite being viewed as a viable alternative to direct state funding. In most provinces divestitures were carried out irregularly, until the government issued regulations and guidelines at the request of the Provincial Commission of Caceres.23 The problem lay in the provinces’ view that the old religious-themed books were of no use to the public library, and their preservation and conservation used up scare funds. By selling off these works, they wished to acquire funds for the purchase more modern, relevant works.24

The Central Commission, however, set increasingly stricter conservation compliance standards and oversight, which aroused criticism from the provinces. These criticisms were justified because the commissions were forced to assume the costs associated with preserving books they considered essentially useless. While the government failed to provide the necessary funds for conservation of these collections, the meager revenues from the sale of books and other articles considered expendable were woefully insufficient to cover the costs of handling library collections.

Finally, regarding books that did not enter public libraries, it is important to highlight certain matters. Such works might be hidden in the same building or off site. It should be noted that books were often hidden in walls and buried in stables. Books hidden in such a way generally deteriorate faster than those held by the state. This suggests an appalling lack of foresight and even spitefulness on the part of those responsible for hiding these materials. Moreover, such persons may well have believed the expropriation of the convents and monasteries would be reversed at some near future time, as had in fact already happened within recent memory. Under this assumption, they perhaps thought books would not be kept in hiding for any significant period of time. Still others, might have thought it better to destroy books before turning them over to the state, since the hiding places they chose in manure strewn stables, caves or behind bricks in damp walls effectively consigned these works to the trash heap.25

The second matter to be discussed is theft. These thefts were committed immediately after the secularization of convents and monasteries by corrupt commissioners or by unassociated individuals who knew of valuable works in libraries and conspired with commission officials to make off with them, which was not difficult, since most buildings did not have guards of any kind. These books generally found their way into private collections. Books stolen well after the confiscation of church property, were sometimes sold for paper recycling. Finally, the lack of means and resources during shipment also led to the removal of a considerable number of works. Those works that finally reached the provincial capital entered another holding situation subject to similar predations.26

The third matter is the destruction of books and even entire libraries, which accounts for a significant loss of the literary and artistic heritage secured through confiscation. In every provincial library, convent and monastery, some portion of books were damaged or completely destroyed. The causes of this damage includes negligence and accidents occurring in the library buildings, during shipment to provincial depositories, and because of the effects of humidity, insects, rodents and human mishandling and omission.27

TYPOLOGY OF PUBLIC LIBRARIES AS A FUNCTION OF COLLECTIONS AND AVAILABLE RESOURCESBefore moving on to describe the various types of libraries created with the collections available (which should be done in accord with Spanish nineteenth-century society), it is interesting to ponder an isolated example of the recreational use of the public library, occurring when a tax collector by the name of Joseph Leis visited Archiepiscopal Public Library in Toledo. Leis viewed these rounds as a sort of leisure, something not generally available to most people. On one particular occasion, he complained of the librarian's refusal to lend him a work, arguing on religious grounds28 and that it had been banned at that time by the then defunct inquisition.29

In addition to observing a rare case of the recreational use of the public library, it is interesting to note how the Church's leading role in culture continued to hold back the development of educational and training entities, leaving these efforts helpless before the majority ultramontane current of the ecclesiastical authorities, which despite its backwardness was still embraced by society at large.30

According to Fernandez Abad (2006: 101), public libraries in the nineteenth century went from performing religious and moral functions to other functions associated with instruction and dissemination of culture. This shift in focus was carried out by changing the nature of collections. As a result, two aspects in the training objectives of libraries were born, the “[...] social-moral and professional–technical.”

This idea is interesting, because libraries holdings in Spain were primarily religious in nature having come from the suppressed orders. As such, changes in the functions of such centers had to wait until economic resources were allocated for the purchase of more modern and appropriate collections in line with the new national and international objectives, as exemplified, according to Fernández Abad (2006), by the uk and us. Escolar Sobrino (1983: 324-325), meanwhile, indicates that public libraries in these two countries were created as “[...] instruments of redemption of the popular classes, for which they should provide healthy entertainment, while keeping them away from vice and improving their job training and performance.”

These arguments also appeared in the formation of liberal library system, which however lacked the funding needed to pursue these objectives. In the American case, public libraries could serve to reinforce democracy, because reading and studying various viewpoints on an issue contribute to the formation of judgment needed to understand issues up for vote (Sobrino School, 1983). Although these principles served to inspire the creation of libraries seeking the formation of informed and socially responsible citizens, in the case of Spain the most widespread conception of public reading centers was quite paternalistically focused on providing an alternative to other forms of leisure considered “pernicious.”31 As stated by Escolar Sobrino (1983), the library is not an end in itself, but rather a “political weapon” serving to further a social agenda.

As for the study of library typology, these centers have been divided into several categories. While it is true that those that have been analyzed as adequately established libraries exhibited serious shortcomings that have not been ignored when making this classification, several of these centers have been included under this heading, because they have been viewed not only in the context of their time, but in comparison to other libraries; that is, these provinces are viewed, on one hand, as responsible for the creation of independent, well-staffed centers as per the criteria used in the mid-nineteenth century by an indebted state at war and, on the other, in accord with a comparison against other provinces, where the deficiencies were much more severe or where they were never established.

As for school-based libraries and those libraries under other agencies, this road was opened by universities. Pursuant to royal order of September 22, 1838, the State transferred powers of management of artistic and literary property (confiscated from the suppressed religious communities) held by scientific and artistic commissions to the universities (in the provinces where these existed). This measure was implemented to minimize the impact of problems such as the state's inability to care for church assets, which without proper handling were likely to deteriorate quickly. Moreover, the literary and art objects were no longer commonly used by religious communities, and by that time had become part of the national heritage. Nonetheless, there was scant social benefit to be derived from holding them, especially since the state did not have the ability to conserve them.

Although the law was apparently clear, sometimes squabbles and disagreements arose regarding the ownership and custody of the books from convents and suppressed monasteries. The biggest problem, however, was that despite the theory that the library was public and open to any user, the fact that it was located within an institution deemed in elite the nineteenth century made the public's access to such collections more difficult than the access offered by independently established libraries. Finally, when a college takes over the collections derived from the confiscations, this did not guarantee better management than that exercised by the commissions.

The state continued to turn over management of the confiscated collections to other centers. Secondary schools were the first keys in the process of founding libraries in the Spanish library system, because as these educational centers grew throughout Spain, the libraries also grew in importance. On the opposite end of the spectrum, we find the declining economic societies of friends of the country, which nonetheless took charge in some provinces and were responsible for the management of collections derived from convents and monasteries. Finally, there are the episcopal and archbishopric libraries, which were the best option for the management of books of a religious nature and making them available an interested public.

Moreover, there is a category of provinces whose management of literary goods from suppressed monasteries and convents was poor or ineffective. This category includes those provinces that never established libraries, where books were kept in depositories or in the ex-convents and –monasteries. “Library” is the term used for these depositaries: some of these were staffed and had operating budgets, but such funding was not sufficient to open the facility to the general public. Occasionally, even where a library was established, the lack of operational budgets made it impossible for them to actually function as such. This category also included libraries which perhaps on paper were established, but for which there is no tangible evidence that they ever were.

In any case, there are abundant examples of mismanagement, lack of interest of the authorities, administrative disorganization at all levels and economic problems of varying severity. There are examples in which energetic commissioners managed to make progress despite the many limitations. At other times, they succumbed to the inertia of the overall situation and activity gradually languished. The situation in these provinces, with shortages and problems of all kinds, ultimately marked the general trend in the formation of liberal library system.

CONCLUSIONSRegarding the social functions of the library, studies have found that the concept of the public library was alien to the vast majority of nineteenth-century society that regarded them unnecessary. Hence the centers created during this period, usually under the auspices of public secondary and higher education institutions, exerted a limited impact and were generally ignored by potential users. Actual users were a small minority who belonged to an elite group of enlightened teachers, students or scholars.

Even while nineteenth-century society at large remained largely Catholic, the bibliographic collections available of a marked religious bent did not meet the characteristic functions of a public library. Regulations issued during the process set a number of objectives to be met in accord with the theoretical liberal proposal; however, budgetary constraints rendered these objectives untenable.

Studies have identified the following features of the nineteenth-century public library: depositories of cultural heritage, social control, public education and vocational training, and community service of teachers and students. It is concluded that provincial public libraries actually served as bibliographic heritage depositories, serving secondary schools and universities. Thus, the resulting library system did not respond to the latent social need of the majority of the population, or to the requirements of the enlightened minority that wanted libraries to be allies in vocational training of the popular sectors. The attitude of the latter was decidedly informed by paternalism and a desire to use libraries, by limiting access to reading material, in a program for social control.

The result was quite short from the initial objectives, and equally short of objectives set during the period of their reformulation. Additionally, the potential of an enormous newly acquired wealth of literary and artistic heritage was never properly exploited. The type of library created was not the result of prior planning, but rather of the management approaches that differed widely from province to province, and which were of an ad hoc nature that merely reacted to conditions on the ground.

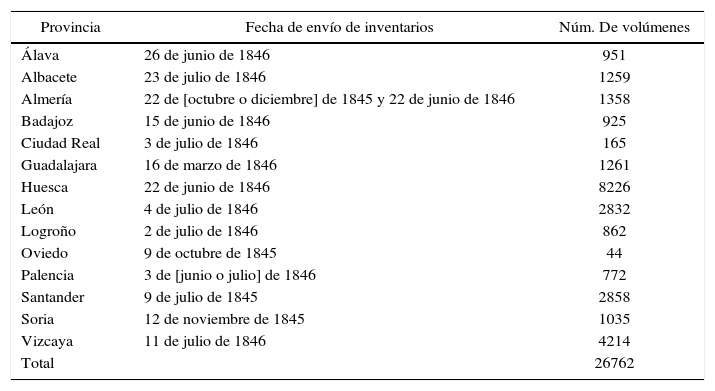

| Provincia | Fecha de envío de inventarios | Núm. De volúmenes |

|---|---|---|

| Álava | 26 de junio de 1846 | 951 |

| Albacete | 23 de julio de 1846 | 1259 |

| Almería | 22 de [octubre o diciembre] de 1845 y 22 de junio de 1846 | 1358 |

| Badajoz | 15 de junio de 1846 | 925 |

| Ciudad Real | 3 de julio de 1846 | 165 |

| Guadalajara | 16 de marzo de 1846 | 1261 |

| Huesca | 22 de junio de 1846 | 8226 |

| León | 4 de julio de 1846 | 2832 |

| Logroño | 2 de julio de 1846 | 862 |

| Oviedo | 9 de octubre de 1845 | 44 |

| Palencia | 3 de [junio o julio] de 1846 | 772 |

| Santander | 9 de julio de 1845 | 2858 |

| Soria | 12 de noviembre de 1845 | 1035 |

| Vizcaya | 11 de julio de 1846 | 4214 |

| Total | 26762 |

Fuente: arabasf, leg. 94-7/2, Circulares y disposiciones generales. Interrogatorios

For additional information on these matters, see García López (2003).

This point is very important in the process of disentitlement, because these documents serve as ownership title to the objects and the acceptance of the old owners (Burón Castro, 1995). This aspect of the process was not, however, emphasized appropriately. This meant that when the science and arts commissions moved to take possession of these assets, they found that the documents needed to guarantee their delivery did not exist (Bello, 1997). This negligence was caused by the lack of funding, indifference and management disorganization. As stated by García López (2003, Chapter 4), on some occasions detailed inventories were in fact made, but these often only provided a lists with the number of books and their weight. which Infantes (1997) has called the “devalued library.” These generally individual and/or damaged tome. In other instances, the inventories were never made because of lack of personnel needed to sit on the civil commissions.

In a letter to the Ministry of Commerce, Instruction and Public Works dated January 20, 1848, the Central Commission petitioned for the proceeds of the sale of artistic objects that occurred more than ten years earlier. “The Central cannot do other than use the occasion of this letter to remind the V.E that on 1837 460,000 reales entered the treasury from the sale of six original paintings by Zurbaran, which were sold in the province of Cádiz at that time (as shown in documents filed in this Secretariat), an amount which be allocated by Rl. orders were providing to the erection of Museums and Libraries.” [sic] (arabasf, leg. 49-7/2).

García López (2002) puts this loss at about three quarters of the total bibliographic collection held by the suppressed religious orders.

For example, as in the ifla/unesco: “A public library is an organization established, supported and funded by the community, either through local, regional or national government or through some other form of community organization. It provides access to knowledge, information and works of the imagination through a range of resources and services and is equally available to all members of the community regardless of race, nationality, age, gender, religion, language, disability, economic and employment status and educational attainment” (ifla, 2001: 8). The purpose of the library shall be “[...]to provide resources and services in a variety of media to meet the needs of individuals and groups for education, information and personal development including recreation and leisure. They have an important role in the development and maintenance of a democratic society by giving the individual access to a wide and varied range of knowledge, ideas and opinions” (ifla, 2001: 8).

For example, the report by Navarrete to the Central Commission dated December 26, 1845, in which tells Logroño that “[...] since his neighbors, framers or tradesmen mostly, cannot devote time to reading, there will be no shortage of people opposing investment [in libraries], monies they believe would be better spent on matters more urgent to the people, rather than on things that they view as useless luxuries [...]” (arabasf, leg. 49-1/2).

“Even today, many people get their news from television broadcasters. Television could be less of a break from the past than commonly believed. In any case, for most people throughout history, books have had more listeners than readers. More than being read, books were heard” (Darnton, 1994: 191). In this regard, when addressing the question of reading aloud, one must not lose sight of the important role of the blind studied by Botrel (1993). In order to reinforce the change in attitude regarding reading aloud, it serves to consider the anecdote discussed by Martínez Martín (2003), where he explains how the behavior of the Countess Espoz y Mina, governess of the infants Isabel and Luisa Fernanda, was criticized for political motives, for reading aloud to her charges when they took rides in a carriage. These criticisms asserted that reading was for one's own edification, and that reading aloud was irreverent and offensive. This event situation was actually addressed in the official gazette, explaining the governess read aloud to the children at their express request and as part of their education. This incident shows, according to the author, that “[...] it was understood by the Church as fomenting passion and as such of a dangerous nature. The society of literate women, as new categories of readers, was the most susceptible to literature, especially the novel, which were read when alone in a private place and in silence. This contrasts to the type of reading that was done collectively aloud, generally associated with sacred texts of religious liturgy […] Reading aloud to share a text was the logical way to relate to the written word. And it had a sacred nature. Also of entertainment and, in fact, it was by its very definition a way of teaching reading” (Martínez Martín, 2003: 141).

For additional information, see Baulo (2003). Additionally, once finished these were often collected in a single volume for sale. For further study, see Carrillo (1974).

For additional study on the relationship between text and image in the nineteenth century press, see Fontbona (2003).

For further information on criticism and moral censure of the novel, see López (1998).

“The prevailing thought before the creation of the monuments commissions and the subsequent formation of museums and libraries. This thought is not so much about gathering and conserving what exists, but rather about establishing an artistic, literary center in each province for known works and those to come, where new acquisitions are gathered as the zeal of the commissions and their resources allows. Add to this consideration that museums and libraries sometimes serve as a means of conserving buildings in which things are kept, thereby freeing them from the ruin that threatens them. The central, guided always by this outlook, has advised that the most noteworthy buildings in each province be provided to house museums and libraries.” Report issued on June 16, 1847, by the Central Commission of the Ministry of Commerce (arabasf, leg. 44-1/2).

Lending libraries that began to take shape in Europe after 1750 received criticism similar to that expressed by Eugenio de Tapia. These libraries were used by students, trades apprentices, women at the fringes of the academic world (as preceptors), military men or secretaries. Their readings consisted of “[...] stories of knights, bandoleers and ghosts; romantic tear-jerkers and family sagas [...]”, and they were written off as “’sellers of moral poison and brothels’ that served their ‘spiritual arsenic’ to young and old, and rich and poor alike”. (Wittmann, 2011: 379-380).

Viñao Frago (1991: 312), concurs with this outlook, stating that in the transition from absolutism to bourgeois liberalism, education policy was focused on “[...] training vassals or subjects, not citizens, who would be loyal and hard-working, with a love of king and nation, disciplined, useful and productive, without questioning the established hierarchy, while ensuring the preeminence of the new middle class legitimized by their service to the nation, the king and the state; that is, by the creation of culture, power and wealth.” Upon analyzing the new education derived from the triumph of political moderantismo, Puelles Benítez (1999) points out that in order to make education universal and free, the focus changed from trying to achieve the enlightenment ideal of equality to an education favoring the primacy of private property. This shift in the focus of education, which was not the same for all, necessarily introduced conceptions of inequality. Thus, education would move from being a force for democratization r revolution to an instrument of power.

“The regional market was based on subsistence agriculture that provided some excess to trade (after the tithe and feudal tax were deducted) for locally produced crafts produced by men who also did some amount of farming. In the national market, in contrast, the social division of labor has intensified: diverse branches of production have become separate from farming and this has taken on a new character, in the sense that there is a tendency to make merchandise to trade for industrial products” (Fontana, 1973: 15). Moreover, with the loss of the colonial market that depended exclusively on Spanish trade, the industrial bourgeoisie realized there many possibilities to develop it, since it was prostrate from the exploitation by the feudal oligarchy: “The ideas in banned books stopped being general principles and became instruments for understanding the world they lived in. Despotism had lost the varnish of enlightenment and had become a brake on progress. Thus, it is understandable that by breaking the long tradition of cooperation with the monarchy, the bourgeoisie of Catalonia now were participants in tentative insurrection aimed at tumbling absolutism and restoring the constitution” (Fontana, 1973: 15).

“It was of little importance that the monuments commissions have an interest in preserving books as simple archeological artifacts; because the truth is that books, because of their specialty, have another feature beyond their relative rarity, which is the property of serving and being in continuous by those who wish or need to consult them; as such, from the moment books are brought together in a more or less established library, they change from being objects into books, and they move out of the domain of archeology to become humble servants to those who need them”.

Notwithstanding the fact that the library existed in the heart of an educational institution, this did not ensure easy access to its holdings for the student community, as was the case in Valencia, according to Paz (1913: 364): “The University Library opened in 1840, keeping hours of 9:00 to 12:00 and 15:00 to 17:00 (or 16:00 to 18:00, in summer); it was closed all afternoon during the month of July and on rainy days in order to prevent students from taking shelter there while waiting for classes. As a consequence of these restrictions, students seldom frequented it. It was rare to see more than 10 or 12 readers. As such the vision of the library's founder regarding its availability to students was far from being accomplished”.

Gil de Zárate (1995, t. I: V-VI) stated that “For those people who can appreciate the benefits [of public instruction], it is without a doubt the first and foremost because of the huge influence it exerts, not only on individuals, but also on the general fate of states. Without good teaching, commerce falters, the arts do not exist, agriculture is pure routine and nothing prospers to enhance the nation. Projects and enterprises are launched in vain; one speaks of public works, of armies, squadrons; nothing is done that is not rickety, miserable; or resources, thus from the government and private parties, sterile efforts are spent that serve only to demonstrate the impotence of a society whose members are paralyzed by ignorance […] In other times, barbarian might have overcome civilization: today victory obeys science, and the most enlightened people are also the most powerful.” [sic].

“It is important to keep in mind, however, that one of the priority functions of schools in the social structure of nineteenth century Spain is the inculcation of values and authoritarian models of disciplined behavior in order to sustain the prevailing social system” Hernández Díaz (1986: 75); Peset and Peset (1974: 436) agree, stating with regard to the Pidal Plan of 1845 that Gil de Zárate designed a well-articulated system that promoted control of the education system by “[...] the social class that had set brought the moderates to power”.

“In this sense, the reforms did no come in response to pressure from the social base or from popular initiatives, but rather, they were driven by a literate, liberal minority that had seized power and was pretending to develop education. These liberal policies drove the creation of the public libraries [...] The diverse educational models have led to the creation of different kinds of libraries. In the nineteenth century, the liberal educational model precipitated the creation of popular public libraries [the author is referring to those created before 1868], though previously the scholastic model had prevailed and were the model informing the creation of university based libraries reserved for the bourgeoisie and clergy. In this way, enlightenment ideas attempted to implement a new approach to teaching, and they had enjoyed the support of the new liberal state born in the image of the French model after the French revolution. Thus, an educational system diametrically opposed to the scholastic model was adopted. This system was at the service of liberal capitalism and was comprised of intellectuals and the new cultivated classes, which would therefore exert influence in library policies. On the basis of these ideas, it is important to point out that the nineteenth century initiatives to establish public libraries hoped to develop an educational model and policies to eradicate illiteracy, which at that time ranged from 80 to 100 percent of the population, and this goal took precedence over any pretention to spread culture or reading” (San Segundo Manuel, 1996: 228).

“Near the great hall of the library, there are places quite suited for these to be shelved at little or no cost, using the shelving that is already in place. Once these are placed there, a single glance will awaken curiosity of the youth who visit this ancient University Center hungry for knowledge and learning about science, and these young people will be able to satisfy their noble desire of enlightenment” (AGA, Educación y Cultura, caja núm. 6.739, carpeta núm. 6.585-37).

For example, the provinces of Zaragoza or Teruel (ARABASF, leg. 54-4/2, y AGA, Educación y Cultura, caja núm. 6.739, carpeta núm. 6.585-4).

In Valencia many difficulties encumbered the collection of the books. As such, the National Library had to invoke the power of the Ministry of the Interior, because the Secretariat of the Civil Government refused to hand the books over. Insofar as the usefulness of the books, both the Granada and Orense commission reported that they were of little use (ABN, 0448/8).

Predicable works were not to be sold off unless they existed in triplicate. Regarding Bibles, historical Works, literature and Antique objects, only duplicates a given edition could be sold off. Single tomes of these material were to be preserved in order to complete sets from the assets of several provinces. The reasons for preserving these works included “[…] for enlightenment on history of literature, typography, for philological study, and for sources of political history in the times when such works were printed.” Finally, on October 1, 1847, a royal order was issued through the auspices of the Ministry of Commerce, Instruction and Public Works that reads as follows: “[…] the commissions of Caseres and all of the other commissions of the country are hereby authorized to sell off all duplicates of a given edition that exist in their libraries, providing proof of sale. To sell off any other work or volume, special authorization must first be secured” (arabasf, leg. 46-5/2).

In this sense, some provincial managers of the assets acquired from the confiscation of religious property had something to say. For example, Juan Guerra, political chief of Caceres wrote to the Central Commission (letter dated August 27, 1846) as follows: “The commission reiterates that it is not inclined to dispose of any type of work however insignificant. There is a big difference between this and wasting time and money in conserving useless duplicate books (which can only serve as wrapping paper in the chemist shop), including them in indexes, shelving them in space needed for other more useful works. The sale of such books could provide funds for binding important books and the purchase of others that cannot be found in the suppressed convents. Nothing of economy, politics, natural history, mathematics, agriculture, etc. is to be found in these tomes [...]” (arabasf, leg. 46-5/2).

Both example come from Toledo, a province with two hidden book depositories, one occurring through chance circumstances and the other thanks to the collaboration of clergy members. Those found buried in dung in stables were found by the buyer of the property when he was carrying out works. Those found in a cave were found thanks to information provided by two clergymen. In both instances, the books were seriously damaged (arabasf, leg. 53-1/2). In Guipúzcoa, most of the books were destroyed in a fire in the village where they were hidden by a Jesuit after the signing of the Vergara Accord (aga, Educación y Cultura, caja núm. 6.735, carpeta núm. 6.581-2).

For example, the provincial governor of Leon wrote (letter dated March 12, 1845) that: “[...] in the constant mobility and in carelessness of their governors, there has been every imaginable consequence of genuine sacking and atrocious and barbarous vandalism [...]” (arabasf, leg. 48-8/2, Asuntos de carácter general). In a letter dated August 14, 1842, the political head of Gerona excused himself before the commission for being unable to locate books removed from the convents during the process of their closing, saying: “[...] the long years that have passed that have been fraught with political turmoil has made it impossible for this commission's diligences to find any of the sought after objects” (arabasf, leg. 47-6/2). Finally, in a letter dated January 27, 1844, to the Ministry of the Interior one Ventura Tien, the political head of the province of Pontevedra, made the following observation that sums up this situation prevailing across the entire country, stating that books seem to be “[...] covered by an impenetrable veil […]” (arabasf, leg. 7-6/2).

In Cádiz, a cry was raised over the condition of 10,000 tomes, “[...] including many valuable literary works, which are lying about at the mercy of vermin, a situation that has been reported to higher authorities.” The letter provided further details of the storage conditions of these books in the same building: “[...] Because of the poor, abandoned state of the building and accumulation of dust, leaky roof and debris falling from the ceiling directly onto and burying them, many of these books are rotting away and becoming completely useless in ever growing numbers [...]” (arabasf, leg. 46-3/2, Monumentos en general). In Logroño, Eustaquio Fernández Navarrete reported on the damage to the Library of San Millán de la Cogolla, which he had visited personally, as follows: “[...] I was filled with sorrow to see many rare, precious books tossed about the beautiful hall of the library. The local people told me they had no idea or their value or merit, and they often used such books to light their fires, or they sold off the books at the price of paper, or the otherwise made use of the scrolls and hard cover boards. Moreover, this looting is done stupidly, causing damage not only to the things they destroy, but also leaving behind the useless remnants of their pillaging” (arabasf, leg. 49-1/2).

My sole activity in times of leisure is to visit the Public Archdiocese Library, where yesterday morning I made a request to the head librarian, one Presbyter Don Pedro Hernandez, to examine the work of Gerundio in order to read one of his critical sermons that interests e quite particularly. I was denied access to the work in no uncertain terms, despite the fact that there are two volumes in the library's holdings, on grounds that the works were banned under the edicts of the defunct Holy Inquisition, and that if I had had one of the special permits to read forbidden works, Presbyter Hernandez would have cancelled it on the spot. Dear Exmo., I deeply respect the religion of my parents and the priesthood that serves it, as the most powerful agency for taming the popular ferocity when its will is aligned with the government in order to all resources in concert and thereby produce the result, but when this backward mode of public instruction of a previous generation and those who are still capable of discussion, and especially those who lend service to the state, resort to the caprices of moaning presbyter, who very likely despises us because of his opinion regarding reciprocal interests, one can imagine disastrous consequences with regard to enlightenment and wisdom sought by Your Highness, whom I humbly obey” (abn, 0007/02).

According to Gil de Zárate (1995: t. 1, vi), “The slab laid upon us by the Inquisition was so heavy that we have not yet been able to throw it off completely: The Holy Office, which has been removed from our institutions, still exerts a malignant influence in our customs, and its ideas still project perniciously and resist taking the road to civilized modernity”.

García López has stated (2002: 129): “Nineteen century society is undergoing a slow evolution, in which the old ways of thought and behavior still had deep roots. With great difficulty, science is overcoming the traditional religious mentality of Catholicism unaccustomed to philosophic reflection, a religiosity that was superficial, or in any case acritical of its own essence”.

Esta función de la biblioteca pública tendría relación con la diferencia que señala Botrel (1996b: 275) entre la visión y el concepto del uso del libro y la lectura entre las clases medias y bajas y la alta sociedad letrada y erudita: “Le divorce entre le goût populaire est consommé […] Autant l’indignation et les condamnations de Campomanes ou d’Iriarte vis-à-vis de leur utilisation pour l’apprentissage de la lecture que les mesures prises les «esprits éclairés» sont impuissantes à contenir -et, a fortiori, abolir- ce qui apparaît comme un véritable phénomène”.