Numerous central banks (cbs) focus on controlling the nominal interest rate (i) to sway the price level and meet the inflation target (πo) nowadays (Taylor, 1993; Bernanke et al., 1999; Woodford, 2003). The i is taken to be the anchor for a low and stable rate of inflation in an open economy model. Yet, some analysts, orthodox and heterodox alike, have challenged this belief arguing that cbs turn to the exchange rate (e) channel and adopt it as a second policy tool with the aim of meeting πo (Svensson, 1999; Hüfner, 2004). The purpose of this paper is to show that the veritable anchor of inflation is neither i nor e, but the wage rate and the unit labour costs (ulc). We conduct econometric analyses based on data from a set of inflation targeting countries. The main empirical findings support our hypothesis regarding the higher importance of wages and the ulcvis-à-vis i and e in the determination of the cpi.

En la actualidad, varios bancos centrales (bcs) centran su política monetaria en el control de la tasa de interés nominal (i) para lograr su objetivo de inflación (πo) (Taylor, 1993; Bernanke et al., 1999; Woodford, 2003). Se concibe a la i como el ancla que hace posible una tasa de inflación baja y estable en un modelo de economía abierta. Esta hipótesis ha sido cuestionada por economistas ortodoxos y heterodoxos con el argumento de que los bcs utilizan el canal del tipo de cambio (e) como un segundo instrumento de política para alcanzar πo (Svensson, 1999; Hüfner, 2004). El objetivo de este artículo es demostrar que la verdadera ancla de la inflación estriba en la tasa de salarios y los costos laborales unitarios (clu), no en la i ni en e. A este efecto, con datos de países que operan con políticas de objetivos de inflación, realizamos un análisis econométrico, cuyos resultados empíricos apoyan nuestra hipótesis.

“Two souls abide, alas, within my breast, and each one seeks for riddance from the other.” Goethe ([1808] 2014). “Fallacies do not cease to be fallacies because they become fashions.” Chesterton ([1935-1936] 2012).

Price stability, that much-coveted policy objective eagerly pursued by many an inflation-targeting central bank (cb), occasionally chased after even with ludicrous doses of bigotry, is nowadays thought out as the upshot of a monetary policy framework where an explicit or an implicit inflation target —specific or within a narrow range— is the monetary authority's paramount concern, and the nominal interest rate its policy operating target. Most importantly —at least for the present study—, the central bank's nominal interest rate is also taken to be the anchor securing both price stability and a supply equilibrium level of output which corresponds to a zero output gap and to a non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment.

Over the last decades, several prominent central banks (cbs), including the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan, among many others, have abandoned the explicit handling of the money supply to impinge on inflation (see, for instance, Bernanke et al., 1999; Arestis, Baddeley, and McCombie, 2005); now they rather focus on controlling the interest rate to influence the price level (Woodford, 2003). As Romer (2000, p. 149) puts it: “(…) one important change is that most central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, now pay little attention to monetary aggregates in conducting policy”.

This new consensus in monetary theory and policy rules puts forth models of inflation and stabilization built on such theoretical foundations as: Knut Wicksell's hypothesis ([1898] 1965) of the natural rate of interest —governed by the marginal productivity of capital— which equates savings and investment bringing them into full employment equilibrium; Milton Friedman's (1977) concept of a unique natural unemployment rate (taken to be the only sustainable rate of unemployment consistent with steady inflation); and the so-called New-Neoclassical Synthesis or New-Keynesian proposition that the interest rate is the unique anchor for an optimal rate of inflation (Woodford, 2003).

Certainly, most modern models of inflation targeting set the central bank's interest rate as the monetary policy instrument (cf.Taylor, 1993; Bernanke and Mishkin, 1997; Bernanke et al., 1999; Woodford, 2003). Yet, whether in practice such interest rate also works as the actual anchor for stable inflation is an open question. Svensson (1998) and Ball (1999), for instance, have emphasised the significant role of the exchange rate as being part and parcel of a monetary conditions index for striking the inflation target. Some heterodox commentators, in turn, have broadmindedly defied the conventional belief on empirical grounds as well, arguing that the exchange rate happens to be the real anchor of the inflation rate —either through sheer currency appreciations (cf.Galindo and Ros, 2008; Bresser-Pereira, 2010) or by way of foreign exchange sterilised interventions (cf.Hüfner, 2004; Mántey, 2009)—. The heterodox case for the inflation stabilising role of the exchange rate is, in a way, tantamount to endorsing Calvo's and Reinhart's (2002) “fear of floating” argument.

The aim of the present paper is to show that modern monetary policy models of inflation targeting, in actual fact, rely on income distribution in order to achieve price stability. Specifically, we argue that, in countries that have adopted inflation targeting monetary policy rules, price inflation has been anchored neither by the nominal interest rate nor by the exchange rate, but by the wage rate. Moreover, the monetary policy interest rate is just the central bank's most preferred instrument and the exchange rate an intermediate target, if anything. This is the main contribution of the present study. Yet, such role of income distribution variables is far from obvious. The artfulness and complexity of the newly enthroned model's monetary transmission mechanism tends to obliterate the function played by wages and unit labour costs in the overall central bank's price stability strategy. These very subtleties, in contrast, favour the mirage of interest rates and/or exchange rates, allegedly, as inflation anchors. Empirical evidence supporting our hypothesis is herein reported.

The outline of the paper is as follows. We start with a brief survey of the relevant literature assessing the role of both the interest rate and the exchange rate in the inflation targeting monetary policy framework; the gist of the importance of income distribution and wages for price stability is succinctly discussed. Having established our main tenet, a few stylised facts about inflation and economic growth follow. We then turn to test our hypothesis empirically; this part contains the econometric analysis and, for obvious reasons, it represents the main component of the document. The final part of the paper sums up and concludes.

A brief survey of the literaturePrice-level targeting, nominal-Gross Domestic Product (gdp) targeting, money-supply targeting or any other level-based approach have been casted-off from the standard toolkit of many cbs that adopted the monetary policy framework identified as inflation-rate targeting (henceforth it). According to Bernanke et al. (1999, p. 8), the it policy is “neither an ironclad rule nor a form of unbridled discretion”, but a monetary policy framework11 “There is no such thing in practice as an absolute rule for monetary policy” (Bernanke et al., 1999, p. 5. Italics in the original). While the 2008-2009 financial crash has rekindled old debates on the neutrality versus the non-neutrality of money, on the importance of additional targets and tools and on the role of central banks, the one-instrument, one-target approach to monetary policy still prevails in central banking practice in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (cf.Blanchard, Dell’Ariccia, and Mauro, 2013).

The it framework belongs to the class of models known qua interest-rate rules as central banking in practice focuses on interest-rate targeting to meet the chosen inflation objective. The rationale behind why cbs are keen on interest-rate targeting is twofold: first, if the economy's LM curve is less stable than the IS curve, such policy framework will be more efficient at stabilising economic activity than, say, Friedman's rule focused on monetary-targeting (Poole, 1970); second, in present-day monetary and financial markets the supply of money and credit is endogenous and most open market operations are “essentially defensive”33 “The day-to-day operations of central banks are essentially ‘defensive’. Their purpose is to ‘neutralize’ the flows of payments between the central bank and the banking system, as these flows create or destruct bank reserves at the central bank” (Lavoie, 2011, p. 46).

The historical provenance of interest-rate rules actually dates back to Knut Wicksell's ([1898] 1965, pp. 62, 70; [1906] 1978) “thorough analysis” of a “purely imaginary case”, namely an “organised credit economy” (i.e. a system with developed credit markets) where all transactions are “effected by means of the Giro system and bookkeeping transfers” (italics in the original). In his pioneering oeuvre, Wicksell swam against the tide of the dominant quantity theory of money (qtm) of his time and set the rate of interest as the true regulator of commodity prices, thus bridging the hiatus between price theory and monetary theory that plagued the classical qtm (see also Myrdal, [1931] 1962; Lindhal, [1939] 1970). Wicksell ([1898] 1968, pp. 98, 100) considered that the qtm was no longer suitable for dealing with “the organic development of a regular movement of prices” in the realm of a modern economy characterised by “a fully developed credit system”. In this case, the fluctuation of the general level of money prices hinges upon the relationship between the loans or money rate of interest (rm) and the natural rate of interest on capital44 “This is necessarily the same as the rate of interest which would be determined by supply and demand if no use were made of money and all lending were effected in the form of real capital goods” (op. cit., p. 102).

Where α measures the sensitivity of price inflation vis-à-vis the interest rate gap. Wicksell took cognisance of the fact that “an exact coincidence of the two rates of interest” was far-fetched because rn “is not fixed”, it “fluctuates constantly” along with its various determinants (ibid.). Hence, according to Knut Wicksell's norm, a market clearing equilibrium situation might call for a fairly awkward condition, a negative natural rate of interest (rn < 0), a scenario that Böhm-Bawerk ([1889] 1891) had entertained momentarily. In this respect, we should like to note in passing, the Wicksellian monetary theory sheds light on some current debates on secular stagnation and the role of monetary policy in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (see Boianovsky, 2004; Summers, 2014).

Since the Wicksellian tradition has of late been resurrected by so-called Neo-Wicksellian monetary theory, and ever since a great many of the new vintages of monetary economists are being schooled to believe in such reinterpretation of the Swedish economist's noteworthy contribution, it appears fair to warn present-day readers’ and draw their attention to Wicksell's continuous critical revision of his own tenets after he had put them forward in 1898. Particularly, he was cognizant of the seemingly insurmountable problems plaguing his own theory of the natural rate of interest. In this regard, he wrote in the preface to the first Swedish edition of his Lectures on Political Economy, II: On Money and Credit ([1906] 1978): “Beside the somewhat too vague and abstract concept natural rate of interest I have defined the more concrete concept normal rate of interest, i.e. the rate at which the demand for new capital is exactly covered by simultaneous savings.” While the Wicksellian theory can be useful for the static analysis of price determination, it appears less so for the dynamic analysis of inflation. As Ohlin (1965, p. xix) contends, while Wicksell grew older intellectually he “came more and more to doubt the solidity of (…) the cornerstone of his monetary theory: —the idea that if the money rate coincided with a normal rate of interest, which brought about equality between savings and investment, the commodity price level would remain constant”55 The first War inflation and the crisis of the Gold Standard burst forth further doubts in Wicksell's mind, as he clearly stated himself in one of his last papers published in the Ekonomisk Tidskrift in 1925: “It should a fortiori prove futile to prevent a rise in prices merely by raising interest rate so as to make it more difficult to obtain credit. A rise in the rate of interest is certainly an almost infallible means of restricting the demand for credit on the part of all producers, but it can hardly have a similar effect on those who merely desire to strengthen their cash position in view of the increase in the volume of exchange.” (Wicksell, 1925, p. 203. Italics in the original).

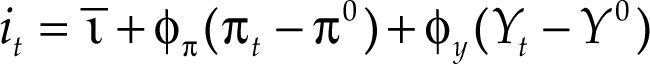

Interest-rate rules have become fashionable with the development of a new consensus around the it approach to conduct monetary policy in a global economy of pure fiat money. The most popular monetary policy rule is the Taylor rule where the central bank is taken to react to both inflation gaps and output gaps through suitable nominal interest rate adjustments aimed at stabilising price inflation and real economic activity. According to Taylor (1993; 1994), the central bank's reaction function takes the form:

Where it and ι¯ are the nominal interest-rate operating target and the neutral long-run interest rate, respectively; πt and π0 are the observed rate of inflation and the inflation target, and γt and γ0 stand for output and potential output, respectively. φπ and φy measure the sensitivity of the policy interest-rate vis-à-vis the inflation gap and the output gap. Optimal interest rate rules must react to these gaps and stabilise them in order to attain inflation stabilisation. Moreover, according to Taylor's principle the central bank must overreact when, alas, πt > π0, i.e., it is to raise it by a proportion greater than the discrepancy between πt and π0 (see Taylor, 1999a; Woodford, 2003).

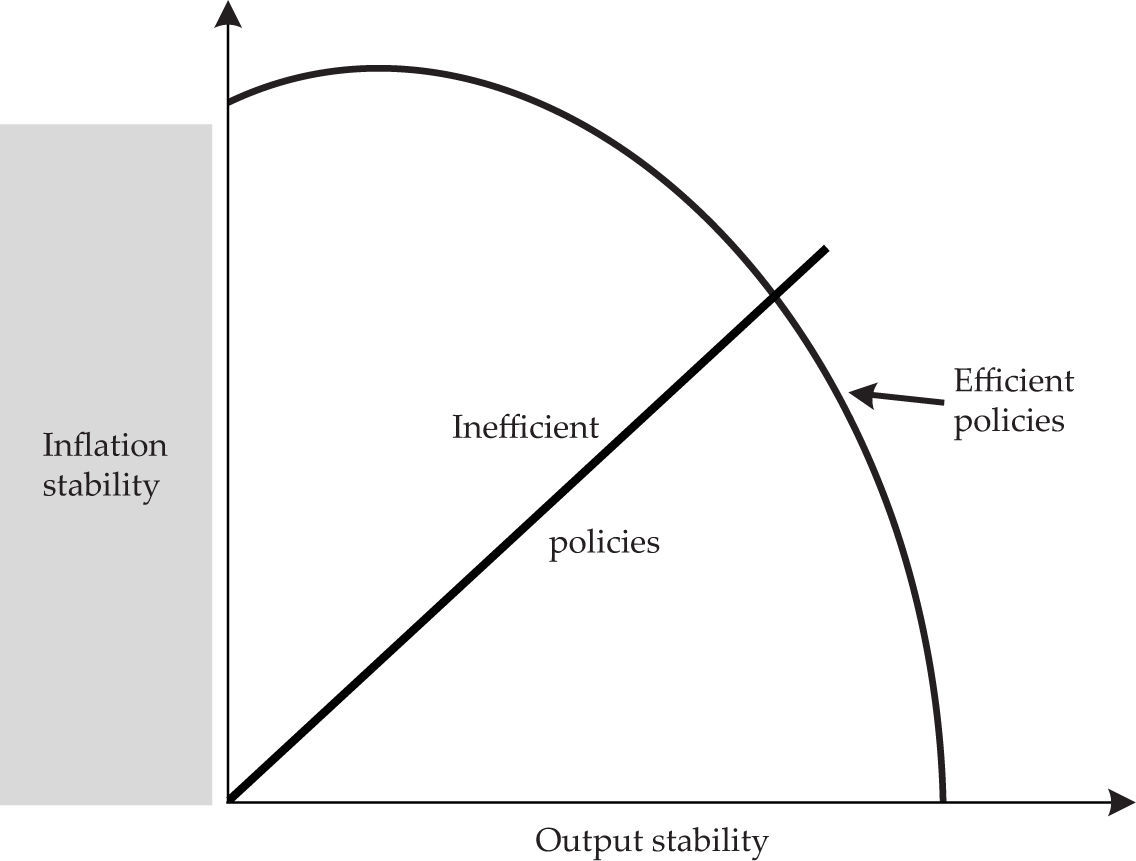

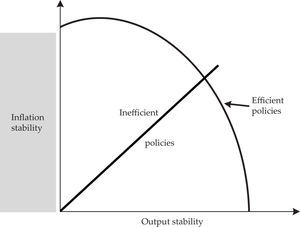

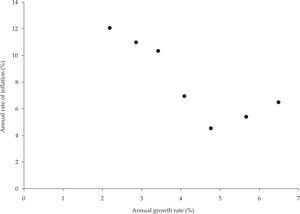

Taylor (1994) introduced a new (variability) trade-off between inflation and output in lieu of the previous trade-off predicated by the Phillips Curve. The latter, he claims, is not adequate for the evaluation of monetary policy rules as it is focused on the levels of inflation and unemployment; Taylor's trade-off focuses on the magnitude of the fluctuations in both inflation and real gdp, their deviations with respect to desired targets. The core assumption of his analysis is that inflation is a demand-driven phenomenon. Figure 1 illustrates Taylor's rule: the production possibilities frontier represents efficient policies, wherein less inflation (output) stability involves the opportunity cost of more output (inflation) stability. Since the economy is subject to exogenous demand and supply shocks that cause both inflation and gdp to fluctuate throughout the business cycle, the duty of the monetary authority is to cushion and keep such shocks effects to a minimum, alternatively choosing between more (less) real gdp stability and less (more) inflation stability. Hence the new variability policy trade-off the central bank is faced with (Taylor, 1999b, pp. 37-44, passim).

Many authors have estimated interest-rate rules66 Woodford (2003) gives an interesting summary.

Officially, a freely floating exchange rate regime is part and parcel of the optimal monetary policy of it central banks. This implies that the exchange rate plays no role whatever in the strategy devised to meet the inflation target. Yet, many commentators rebut such assumption arguing that exchange rates and import prices influence inflation, pass-through effects of exchange rate fluctuations and commodity price oscillations alter domestic inflation. At least in developing economies it central banks must consider these and other supply-side shocks that, at any rate, reduce the effectiveness of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Hence it central banks in these countries have incentives to turn to the exchange rate channel and adopt it as a second policy tool (allegedly faster than the nominal interest rate) with the aim of hitting the target (see Svensson, 1999; Hüfner, 2004; Edwards, 2006; Mántey, 2009; Benlialper and Cömert, 2016; Benlialper, Cömert, and Öcal, 2017). But the exchange rate not only does play a role; the it central banks in developing countries deliberately follow an asymmetric exchange rate policy, enduring exchange rate appreciation and preventing major depreciation pressures (Ho and McCauley, 2003; Roger and Stone, 2005; Galindo and Ros, 2008). Benlialper, Cömert, and Öcal (2017) estimate a nonlinear monetary policy reaction function for a group of developing countries, their chief findings being that it central banks in such countries behave asymmetrically with regards exchange rate fluctuations, loosening monetary policy in face of appreciations and tightening it in face of depreciations. Furthermore, this asymmetric policy stance is an idiosyncratic feature of it developing countries.

On net, this vast literature furnishes amazing analyses of the intricacies of the it monetary policy framework in a wide range of aspects, from the nominal interest rate to the exchange rate. Nonetheless, the role of the wage rate and the unit labour costs in the new monetary policy consensus appear to remain in oblivion. The wage rate is the price of labour-power; in this regard, wages are linked “with other prices and economic quantities” (Dobb, [1928] 1959, p. 88). Actually, most prices of industrial goods are shaped on a mark-up over unit labour costs, regardless of the dominant market structure in the economy. As Lavoie (2014, p. 542) argues, “the money wage is the exogenous factor explaining the price level that orthodox authors have sought.” Since money wages are exogenously determined in the short-term (real wages are endogenous), the rate of inflation tinker with the extent to which money wage increases exceed the increment in average labour productivity77 “The proximate determinant of inflation is then the rate at which nominal money wages rise in excess of the growth rate of average labour productivity. To the extent money wages grow more rapidly than the growth of labour productivity, unit labour costs and therefore the price level will rise accordingly, as follows: p˙=W˙−z˙ where z˙ is the growth rate of labour productivity” (Moore, 1979, p. 133). The classical political economists and Marx also recognized the importance of income distribution and labour productivity in the formation of supply prices (see Pasinetti, 1979).

Does the foregoing analysis mean that wage inflation is necessarily the main cause of price inflation? Moreover, inflation moves pro-cyclically along with output growth and higher rates of employment. Keynes ([1936] 1964, pp. 301-303) distinguishes between ‘positions of semi-inflation’ —when increasing levels of effective demand lead to discontinuous changes in wages “not fully in proportion to the rise in the price of wage-goods”— and ‘positions of absolute inflation’ or “true inflation” —when effective demand expands “in circumstances of full employment”, in which case no further expansion in output will be forthcoming and the effect of the increasing demand will be reflected fully in higher unit costs—. Only in this latter case can it be said that wage inflation is the main cause of price inflation. However, this is a far-fetched scenario.

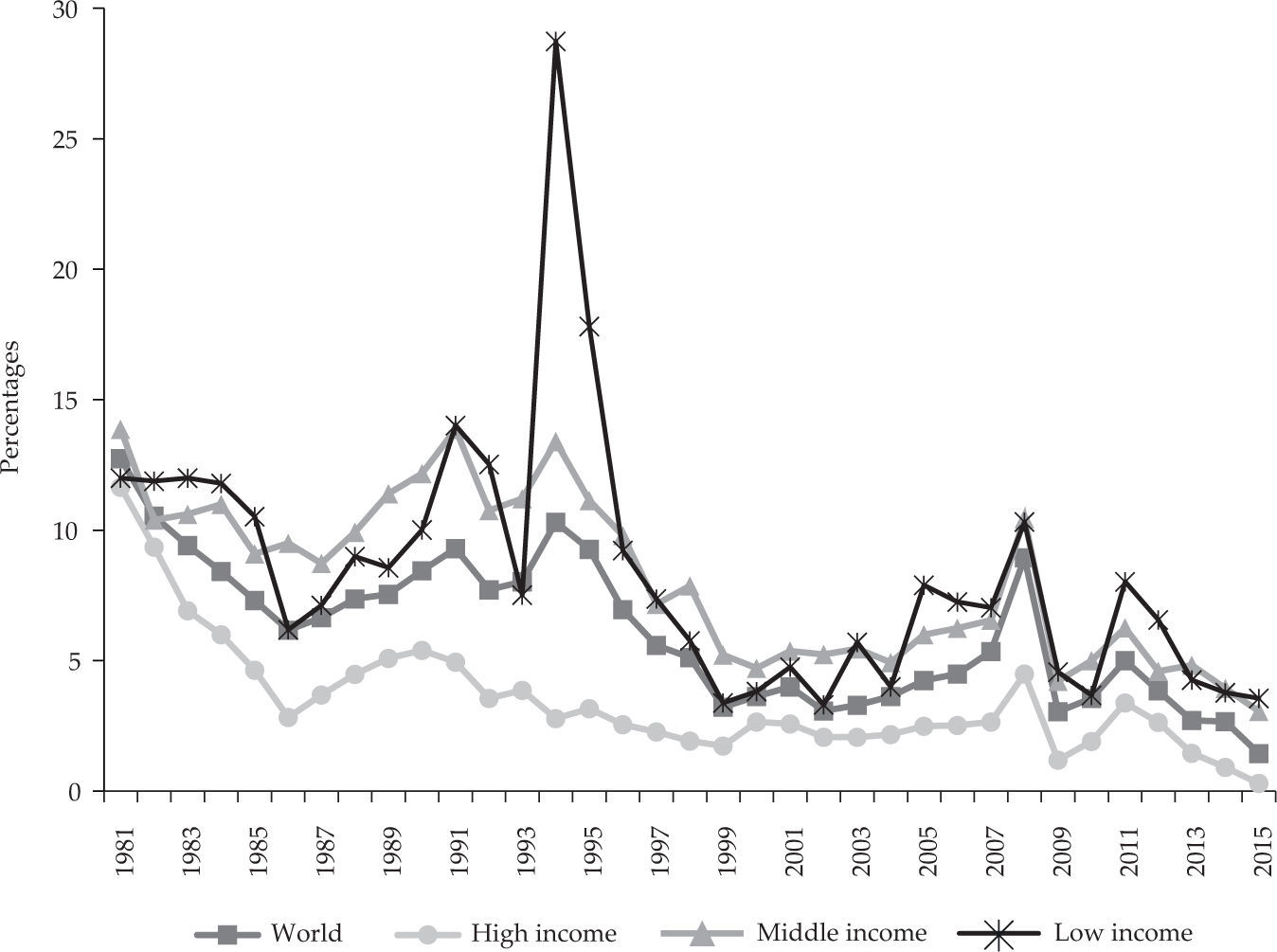

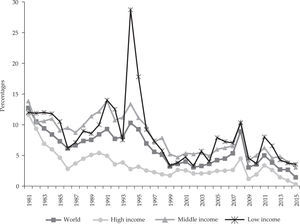

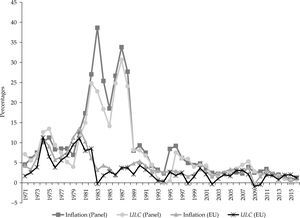

Some stylised factsA low and stable inflation has been predicated as the panacea for optimal economic growth worldwide. Annual rates of inflation in high-income countries have been on a downward trend since the mid-eighties and in the rest of the world at least since the mid-nineties —with a couple of short-lived pauses at the beginning of the 1990s and the mid-2000s—. Remarkably, the annual rate of inflation of all high, middle and low income groups of countries has been lower than 5% since 2013 (see Graph 1).

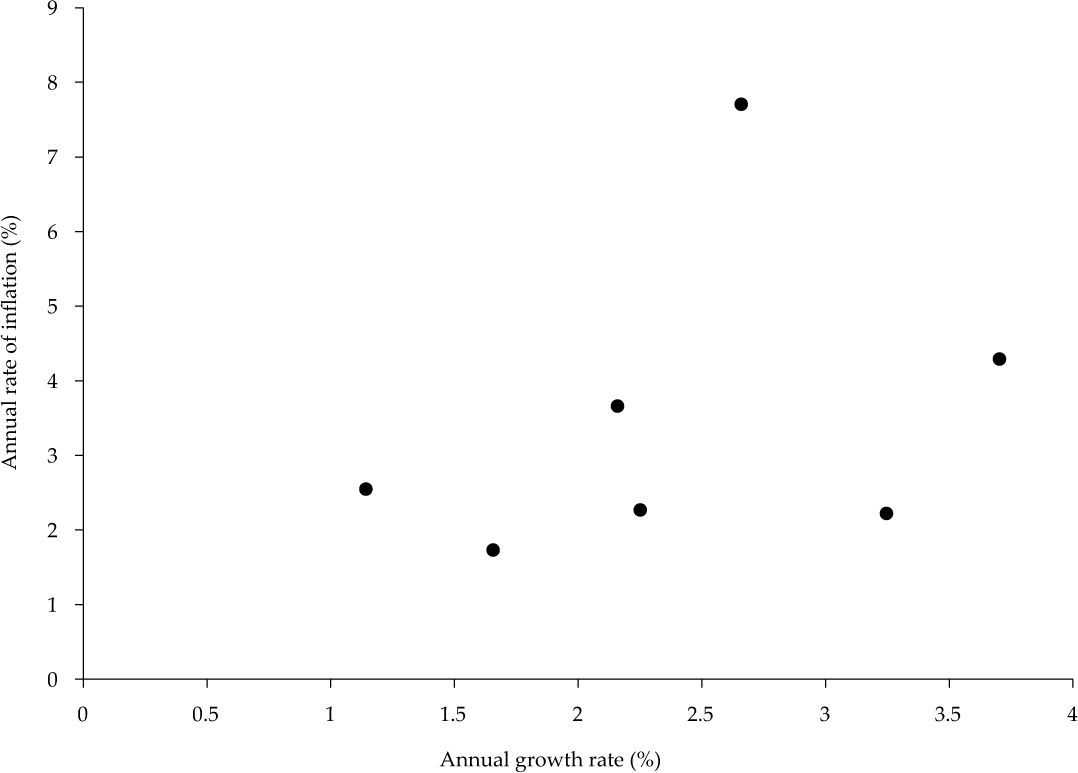

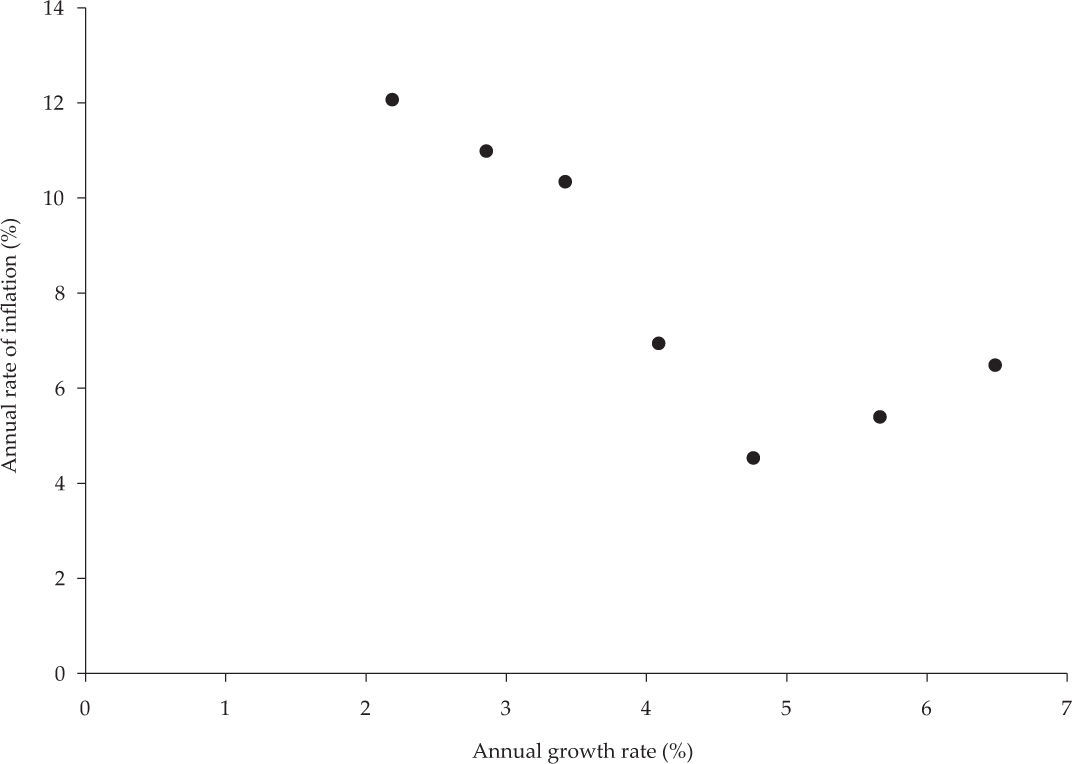

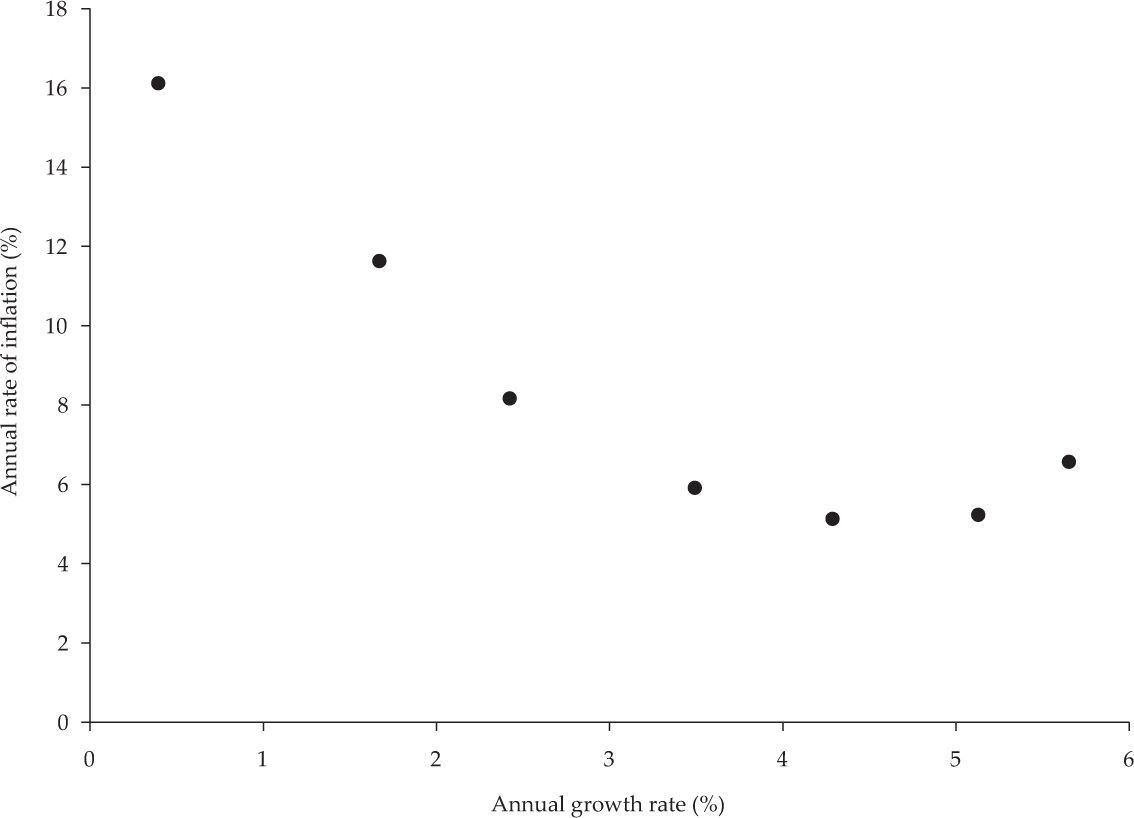

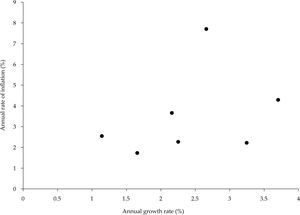

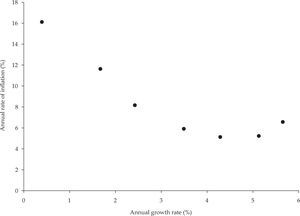

It is also worth mentioning that the relationship between economic growth rates and inflation rates for the various countries diverge, signalling different opportunity costs and sacrifice ratios in terms of forgone output growth associated with the disinflation process. It appears that the magnitude of the opportunity cost varies in accordance with the relationship between output growth and inflation of each country. For example, whilst in the case of the high income level group of countries such relationship looks positive, for those countries in the middle and low income groups it looks like an U-shape (see Graphs 2, 3 and 4). So, high growth rates of output can occur along with high inflation rates in all three groups of countries, but in the cases of middle and low income countries it is also possible to observe low growth rates hand in hand with high inflation rates, a situation that induces contractionary policies in depressive regimes. Clearly, high-income countries, middle-income and low-income economies do not exhibit the same pattern of correlations between inflation and economic growth. This stylised fact should suffice to understand that one-size does not fit all in terms of targeting price stability.

The following countries are considered in our empirical analysis: Australia, Canada, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Poland and the United Kingdom. We look at these countries both individually and jointly within a non-balanced panel. Moreover, we ponder the United States as a benchmark for two reasons: First, we expect that the nominal exchange rate of the dollar will affect domestic inflation differently in comparison with the effect of nominal exchange rate in other countries included in our sample. Second, although the United States explicitly adopted the it regime only in 2012, the Fed has been implementing it implicitly since the late 1970s, starting with Volcker's administration (see Goodfriend, 2005)88 The sub-periods of analysis for the United States are before 1982 and 1982-2015; for other countries are prior to-it and it.

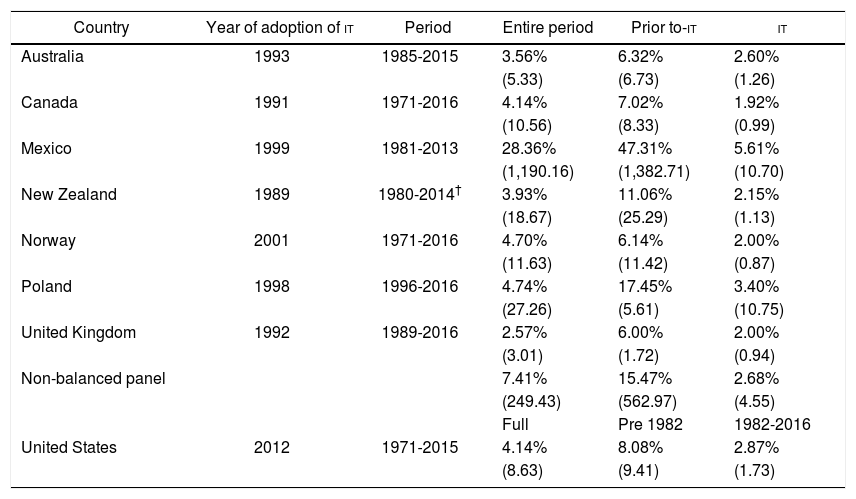

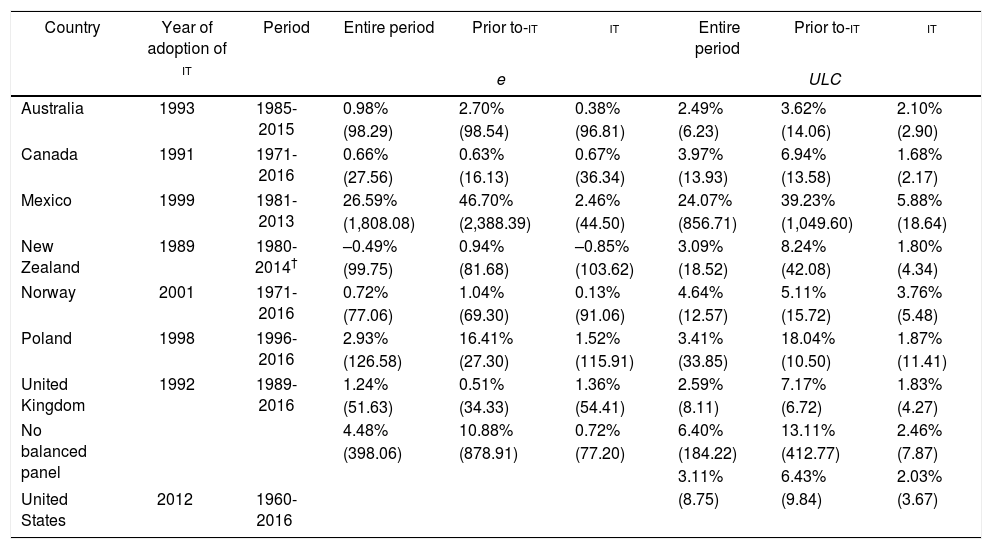

Table 1 shows the average and the variance of the annual rate of inflation of the countries under consideration for the whole period and the sub-periods prior to it and during it. The adoption of the it regime brought about a reduction in the average annual rate of inflation and, with the exception of Poland, a decrease in the variance of the annual rate of inflation99 In the case of Poland, we only have two observations for the sub-period prior to it, hence the comparison between sub-periods is weak.

Average and variance (in parentheses) of the annual rate of inflation11.

| Country | Year of adoption of it | Period | Entire period | Prior to-it | it |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 1993 | 1985-2015 | 3.56% | 6.32% | 2.60% |

| (5.33) | (6.73) | (1.26) | |||

| Canada | 1991 | 1971-2016 | 4.14% | 7.02% | 1.92% |

| (10.56) | (8.33) | (0.99) | |||

| Mexico | 1999 | 1981-2013 | 28.36% | 47.31% | 5.61% |

| (1,190.16) | (1,382.71) | (10.70) | |||

| New Zealand | 1989 | 1980-2014† | 3.93% | 11.06% | 2.15% |

| (18.67) | (25.29) | (1.13) | |||

| Norway | 2001 | 1971-2016 | 4.70% | 6.14% | 2.00% |

| (11.63) | (11.42) | (0.87) | |||

| Poland | 1998 | 1996-2016 | 4.74% | 17.45% | 3.40% |

| (27.26) | (5.61) | (10.75) | |||

| United Kingdom | 1992 | 1989-2016 | 2.57% | 6.00% | 2.00% |

| (3.01) | (1.72) | (0.94) | |||

| Non-balanced panel | 7.41% | 15.47% | 2.68% | ||

| (249.43) | (562.97) | (4.55) | |||

| Full | Pre 1982 | 1982-2016 | |||

| United States | 2012 | 1971-2015 | 4.14% | 8.08% | 2.87% |

| (8.63) | (9.41) | (1.73) |

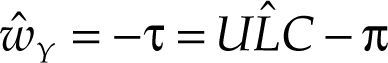

The disinflation process experienced by it countries involved a nominal exchange rate appreciation. However, the growth differential of lp and w, i.e., the growth rate of ULC also played a fundamental role in the disinflation process, a fact supporting our hypothesis. Let a mark-up equation for the determination of prices be written:

Where P is the unit price, τ is the mark-up percentage over the unit total cost, UMC is the unit imported input-costs, which is affected by e. Equation [3] provides a benchmark for assessing the growth rates of e and ULC as determinants of the rate of inflation.

Table 2 presents the average and the variance of the annual growth rates of e and ULC for the entire period and the sub-periods prior to it and during it. As can be shown, the annual growth rate of e decreased during the sub-period it with respect to the sub-period prior-it in five out of the seven countries of our sample; in Canada e changed very little, the United Kingdom's e increased and for the whole panel e decreased. On the other hand, the variance of the annual growth rate of e for the panel shrank during the sub-period it with respect to the prior-it one, despite the variance of five out of seven countries exhibited an increase. Mexico and Poland experienced a decline in their variance of the annual growth rate of e1010 Actually, if Mexico is excluded the panel's variance of the annual rate of depreciation of e increases from 60.09 to 80.51. As for Poland, one must bear in mind the caveat referred to the small number of observations for the sub-period prior to-it. The year of adoption of the it approach is based on Hammond (2012), except for the case of Mexico, which was taken from Galindo and Ros (2008).

Average and variance (in parentheses) of the annual growth rates of e and ULC.

| Country | Year of adoption of it | Period | Entire period | Prior to-it | it | Entire period | Prior to-it | it |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e | ULC | |||||||

| Australia | 1993 | 1985-2015 | 0.98% | 2.70% | 0.38% | 2.49% | 3.62% | 2.10% |

| (98.29) | (98.54) | (96.81) | (6.23) | (14.06) | (2.90) | |||

| Canada | 1991 | 1971-2016 | 0.66% | 0.63% | 0.67% | 3.97% | 6.94% | 1.68% |

| (27.56) | (16.13) | (36.34) | (13.93) | (13.58) | (2.17) | |||

| Mexico | 1999 | 1981-2013 | 26.59% | 46.70% | 2.46% | 24.07% | 39.23% | 5.88% |

| (1,808.08) | (2,388.39) | (44.50) | (856.71) | (1,049.60) | (18.64) | |||

| New Zealand | 1989 | 1980-2014† | –0.49% | 0.94% | –0.85% | 3.09% | 8.24% | 1.80% |

| (99.75) | (81.68) | (103.62) | (18.52) | (42.08) | (4.34) | |||

| Norway | 2001 | 1971-2016 | 0.72% | 1.04% | 0.13% | 4.64% | 5.11% | 3.76% |

| (77.06) | (69.30) | (91.06) | (12.57) | (15.72) | (5.48) | |||

| Poland | 1998 | 1996-2016 | 2.93% | 16.41% | 1.52% | 3.41% | 18.04% | 1.87% |

| (126.58) | (27.30) | (115.91) | (33.85) | (10.50) | (11.41) | |||

| United Kingdom | 1992 | 1989-2016 | 1.24% | 0.51% | 1.36% | 2.59% | 7.17% | 1.83% |

| (51.63) | (34.33) | (54.41) | (8.11) | (6.72) | (4.27) | |||

| No balanced panel | 4.48% | 10.88% | 0.72% | 6.40% | 13.11% | 2.46% | ||

| (398.06) | (878.91) | (77.20) | (184.22) | (412.77) | (7.87) | |||

| 3.11% | 6.43% | 2.03% | ||||||

| United States | 2012 | 1960-2016 | (8.75) | (9.84) | (3.67) | |||

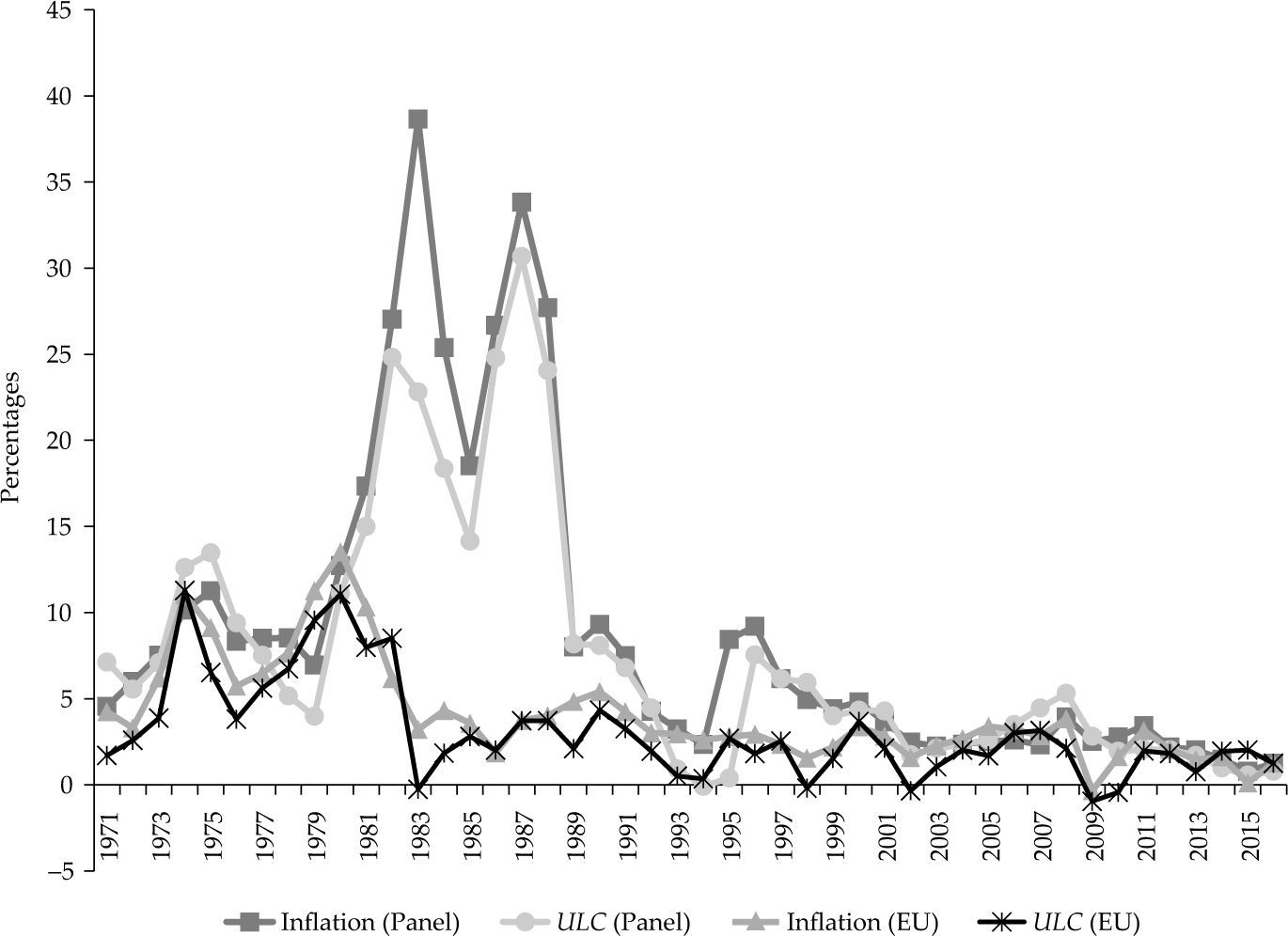

Interestingly, in all countries in the sample, including the United States, and the panel as a whole, both the average and the variance of the annual growth rate of ULC decreased, signalling the higher importance of ULC —vis-à-vis e— as a determinant of the rate of inflation. Likewise, this is also indicative of the higher relevance of controlling the growth rate of ULC for reining in the rate of inflation. Graph 5 displays the above finding visually.

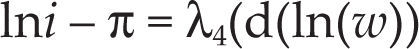

In order to substantiate the above tenet more rigorously, the following long-run equation is estimated for each of the countries in our sample and for the panel as a whole1212 Our specification skips the demand-side of the determination of prices. As Keynes ([1936] 1964) contended, the growth differential between wages and labor productivity is a key determinant of prices. Furthermore, as will be shown later, the causality line developed in the present research implies modifications of the functional distribution of income against the compensations of employees as a percentage of added value. These changes impart disinflationary effects through the contraction of aggregate demand.

Where ln is the natural logarithm operator; βi are the parameters to be estimated, u is an error term (this term's one-period lag is used as the long-run deviation of the CPI with respect to its long-run equilibrium value), the subscript t stands for time.

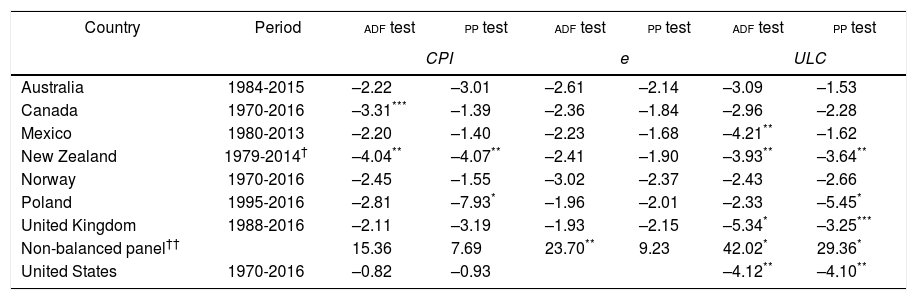

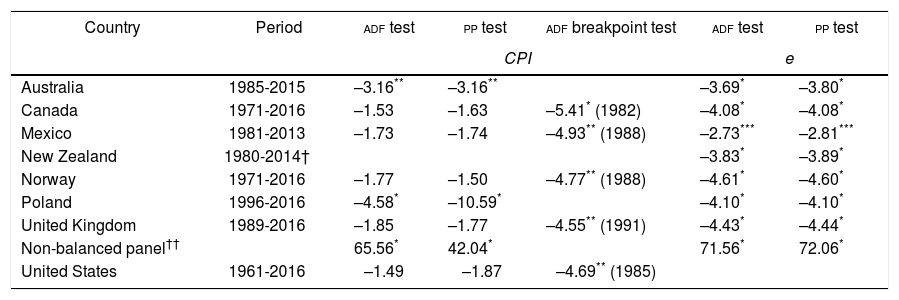

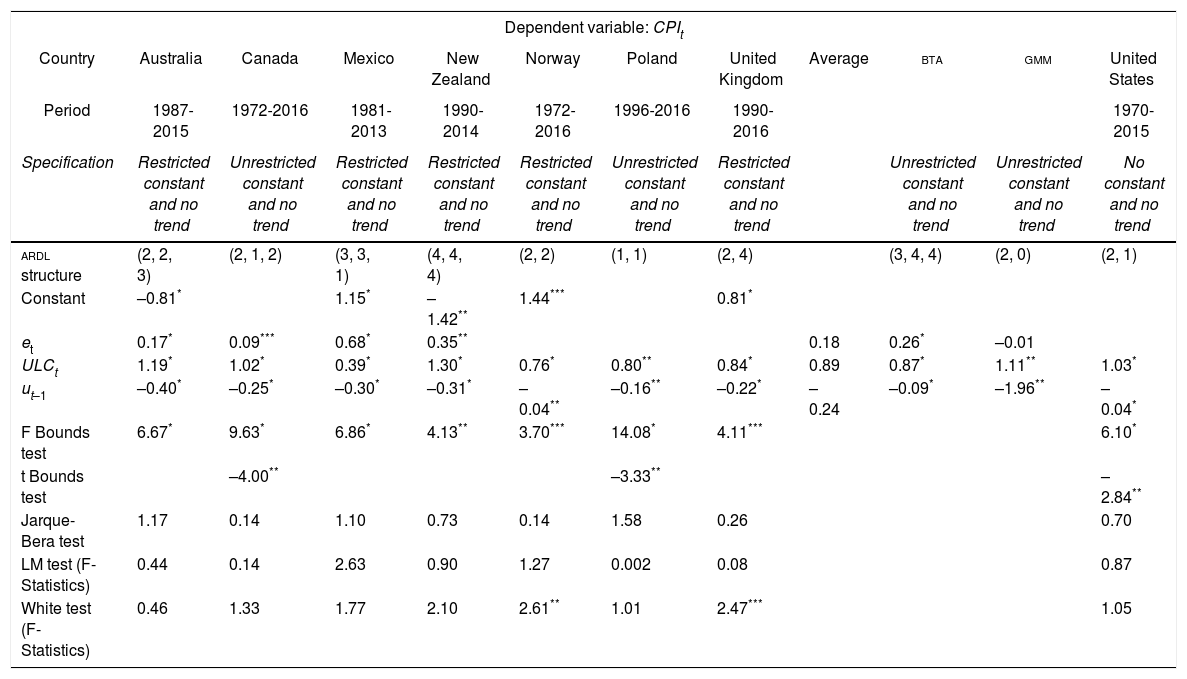

Before estimating equation [4], we present the unit-root tests corresponding to each of the time-series used for each country and for the whole panel (see Tables 3a and 3b). As can be shown, with the exception of New Zealand's CPI and New Zealand's ULC, the United Kingdom's ULC, the United States's ULC and the panel's ULC, which are stationary, the rest of the time series are integrated of order one. We estimate the long-run equation [4] for the CPI using the bound test approach cointegration methodology (bta) for each country and for the panel; the Generalized Method of Moments (gmm) was also used for the whole panel. We report the simple average of the estimated parameters for each country and, with the aim of confirming robustness of our estimations, compared them with those obtained through the panel methodologies (see Tables 4 and 5)1313 The methodologies used in the estimation of equation [4] follow Pesaran, Shin and Smith (1999), where the long-run coefficients are restricted to be identical for each country in the panel, whilst the short-run coefficients and the variances of the errors are different from one another. According to Pesaran et al., this methodology suffers from the same problem as other methods when the time-period used is short, as in our case. Hence the authors estimate the long-run equation using alternative methodologies to double check and compare the robustness of their results.

Unit root tests for CPI, e and ULC (levels).

| Country | Period | adf test | pp test | adf test | pp test | adf test | pp test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPI | e | ULC | |||||

| Australia | 1984-2015 | –2.22 | –3.01 | –2.61 | –2.14 | –3.09 | –1.53 |

| Canada | 1970-2016 | –3.31*** | –1.39 | –2.36 | –1.84 | –2.96 | –2.28 |

| Mexico | 1980-2013 | –2.20 | –1.40 | –2.23 | –1.68 | –4.21** | –1.62 |

| New Zealand | 1979-2014† | –4.04** | –4.07** | –2.41 | –1.90 | –3.93** | –3.64** |

| Norway | 1970-2016 | –2.45 | –1.55 | –3.02 | –2.37 | –2.43 | –2.66 |

| Poland | 1995-2016 | –2.81 | –7.93* | –1.96 | –2.01 | –2.33 | –5.45* |

| United Kingdom | 1988-2016 | –2.11 | –3.19 | –1.93 | –2.15 | –5.34* | –3.25*** |

| Non-balanced panel†† | 15.36 | 7.69 | 23.70** | 9.23 | 42.02* | 29.36* | |

| United States | 1970-2016 | –0.82 | –0.93 | –4.12** | –4.10** | ||

Note: All the series are expressed in natural logarithms. All tests include intercept and trend. The number of lags were determined on the basis of the Schwarz information criterion and the Newey-West statistical criterion, respectively.

Unit root tests for CPI, e and ULC (first differences).

| Country | Period | adf test | pp test | adf breakpoint test | adf test | pp test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPI | e | |||||

| Australia | 1985-2015 | –3.16** | –3.16** | –3.69* | –3.80* | |

| Canada | 1971-2016 | –1.53 | –1.63 | –5.41* (1982) | –4.08* | –4.08* |

| Mexico | 1981-2013 | –1.73 | –1.74 | –4.93** (1988) | –2.73*** | –2.81*** |

| New Zealand | 1980-2014† | –3.83* | –3.89* | |||

| Norway | 1971-2016 | –1.77 | –1.50 | –4.77** (1988) | –4.61* | –4.60* |

| Poland | 1996-2016 | –4.58* | –10.59* | –4.10* | –4.10* | |

| United Kingdom | 1989-2016 | –1.85 | –1.77 | –4.55** (1991) | –4.43* | –4.44* |

| Non-balanced panel†† | 65.56* | 42.04* | 71.56* | 72.06* | ||

| United States | 1961-2016 | –1.49 | –1.87 | –4.69** (1985) | ||

| Country | Period | adf test | pp test | adf breakpoint test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ULC | ||||

| Australia | 1985-2015 | –4.34* | –4.38* | |

| Canada | 1971-2016 | –2.14 | –2.00 | –4.90** (1982) |

| Mexico | 1981-2013 | –2.77*** | –1.44 | –5.59* (1988) |

| New Zealand | 1980-2014† | |||

| Norway | 1971-2016 | –3.45** | –2.75*** | |

| Poland | 1996-2016 | –3.69** | –7.18* | |

| United Kingdom | 1989-2016 | |||

| Non-balanced panel†† | ||||

| United States | 1961-2016 | |||

Note: All the series are expressed in natural logarithms. All tests include only intercept. In the adf breakpoint tests the existence of an innovative shock was assumed, except in the case of the CPI of the United Kingdom. In this latter case we assumed the existence of an additive shock. Values in parentheses denote the years in which the break was experimented. The number of lags used were determined on the basis of the Schwarz information criterion and the Newey-West statistical criterion, respectively.

Estimation of the long-run elasticities of the CPI with respect to e and ULC for the entire period.

| Dependent variable: CPIt | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Australia | Canada | Mexico | New Zealand | Norway | Poland | United Kingdom | Average | bta | gmm | United States |

| Period | 1987-2015 | 1972-2016 | 1981-2013 | 1990-2014 | 1972-2016 | 1996-2016 | 1990-2016 | 1970-2015 | |||

| Specification | Restricted constant and no trend | Unrestricted constant and no trend | Restricted constant and no trend | Restricted constant and no trend | Restricted constant and no trend | Unrestricted constant and no trend | Restricted constant and no trend | Unrestricted constant and no trend | Unrestricted constant and no trend | No constant and no trend | |

| ardl structure | (2, 2, 3) | (2, 1, 2) | (3, 3, 1) | (4, 4, 4) | (2, 2) | (1, 1) | (2, 4) | (3, 4, 4) | (2, 0) | (2, 1) | |

| Constant | –0.81* | 1.15* | –1.42** | 1.44*** | 0.81* | ||||||

| et | 0.17* | 0.09*** | 0.68* | 0.35** | 0.18 | 0.26* | –0.01 | ||||

| ULCt | 1.19* | 1.02* | 0.39* | 1.30* | 0.76* | 0.80** | 0.84* | 0.89 | 0.87* | 1.11** | 1.03* |

| ut–1 | –0.40* | –0.25* | –0.30* | –0.31* | –0.04** | –0.16** | –0.22* | –0.24 | –0.09* | –1.96** | –0.04* |

| F Bounds test | 6.67* | 9.63* | 6.86* | 4.13** | 3.70*** | 14.08* | 4.11*** | 6.10* | |||

| t Bounds test | –4.00** | –3.33** | –2.84** | ||||||||

| Jarque-Bera test | 1.17 | 0.14 | 1.10 | 0.73 | 0.14 | 1.58 | 0.26 | 0.70 | |||

| LM test (F-Statistics) | 0.44 | 0.14 | 2.63 | 0.90 | 1.27 | 0.002 | 0.08 | 0.87 | |||

| White test (F-Statistics) | 0.46 | 1.33 | 1.77 | 2.10 | 2.61** | 1.01 | 2.47*** | 1.05 | |||

Note: All the series are expressed in natural logarithms. The ardl structure was determined on the basis of the Schwarz information criterion. White heteroscedasticity tests were conducted using cross terms in the cases of Canada, Norway, Poland and the United States. Standard errors and covariance matrices are adjusted for heteroscedasticity in the appropriate cases. Lags of the dependent variable and the independent variables were used as instruments in the estimation for the gmm methodology; the error terms do not exhibit autocorrelation neither of first nor of second order. The rest of the relevant statistics for each of the estimations were omitted for the sake of brevity. However, they are available from the authors upon request.

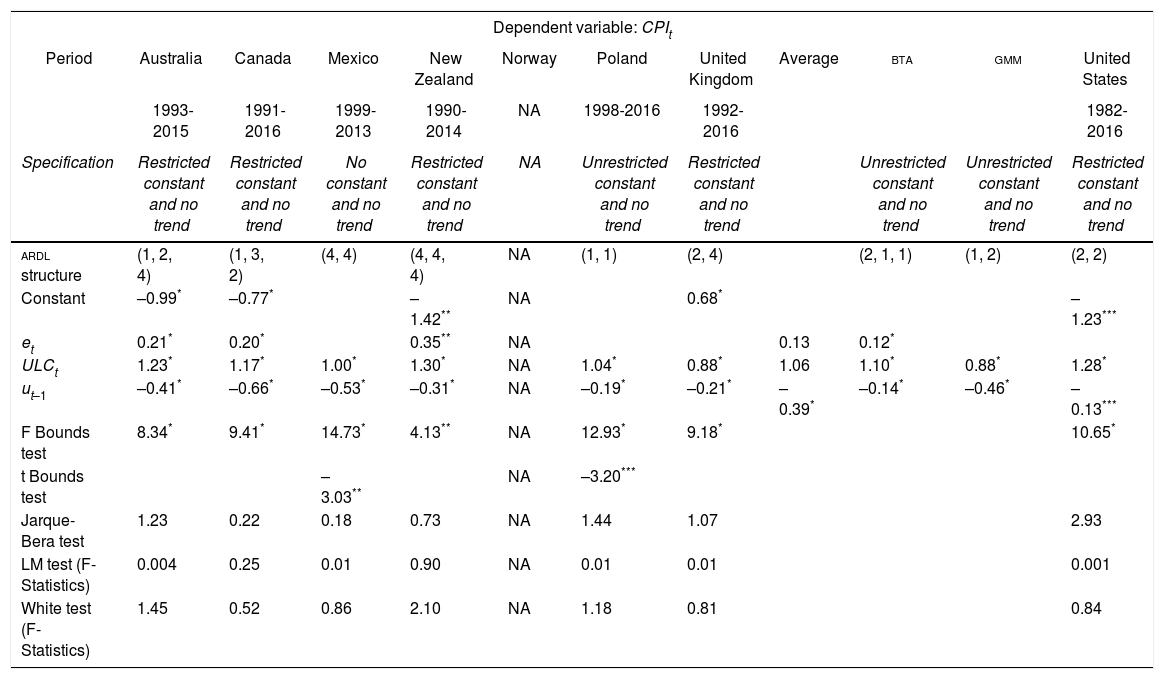

Estimation of the long-run elasticities of the CPI with respect to e and ULC for the it sub-period.

| Dependent variable: CPIt | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Australia | Canada | Mexico | New Zealand | Norway | Poland | United Kingdom | Average | bta | gmm | United States |

| 1993-2015 | 1991-2016 | 1999-2013 | 1990-2014 | NA | 1998-2016 | 1992-2016 | 1982-2016 | ||||

| Specification | Restricted constant and no trend | Restricted constant and no trend | No constant and no trend | Restricted constant and no trend | NA | Unrestricted constant and no trend | Restricted constant and no trend | Unrestricted constant and no trend | Unrestricted constant and no trend | Restricted constant and no trend | |

| ardl structure | (1, 2, 4) | (1, 3, 2) | (4, 4) | (4, 4, 4) | NA | (1, 1) | (2, 4) | (2, 1, 1) | (1, 2) | (2, 2) | |

| Constant | –0.99* | –0.77* | –1.42** | NA | 0.68* | –1.23*** | |||||

| et | 0.21* | 0.20* | 0.35** | NA | 0.13 | 0.12* | |||||

| ULCt | 1.23* | 1.17* | 1.00* | 1.30* | NA | 1.04* | 0.88* | 1.06 | 1.10* | 0.88* | 1.28* |

| ut–1 | –0.41* | –0.66* | –0.53* | –0.31* | NA | –0.19* | –0.21* | –0.39* | –0.14* | –0.46* | –0.13*** |

| F Bounds test | 8.34* | 9.41* | 14.73* | 4.13** | NA | 12.93* | 9.18* | 10.65* | |||

| t Bounds test | –3.03** | NA | –3.20*** | ||||||||

| Jarque-Bera test | 1.23 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.73 | NA | 1.44 | 1.07 | 2.93 | |||

| LM test (F-Statistics) | 0.004 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.90 | NA | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.001 | |||

| White test (F-Statistics) | 1.45 | 0.52 | 0.86 | 2.10 | NA | 1.18 | 0.81 | 0.84 | |||

Note: All the series are expressed in natural logarithms. The ardl structure was determined on the basis of the Schwarz information criterion. White heteroscedasticity tests were made using cross terms for the cases of Poland and the United States. Lags of the dependent variable and the independent variables were used as instruments in the estimation of the gmm; the error terms do not exhibit autocorrelation neither of first nor second order. The rest of the relevant statistics for each of the estimations were omitted for the sake of brevity. Yet, they are available from the authors upon request.

Our estimations for the whole period reveal a number of characteristics (see Table 4): First, the ULC is relevant in the determination of the CPI for all the countries considered, including the United States. In contrast, in three such countries (Norway, Poland and the United Kingdom), e does not exhibit a long-run relationship with the CPI. Only in Mexico the elasticity of the CPI with respect to e is higher than with respect to ULC. Moreover, the simple average of the estimated elasticity for each individual country is not very different from the estimated parameters for the panel based on the bta cointegration methodology; the simple average of the estimated elasticity of the CPI with respect to e for each country is equal to 0.18, whilst the bta cointegration estimated parameter is equal to 0.26. On the other hand, the simple average of the estimated elasticity of the CPI with respect to the ULC for each country is almost the same as the one estimated for the panel using the bta cointegration methodology (0.89 versus 0.87). Likewise, although the estimated elasticities for the panel based on the gmm methodology are very different from the simple average of the estimated elasticities of the CPI with respect to e and the ULC for each country, the estimated parameters support our hypothesis about the higher importance of the ULC vis-à-vis e in the determination of the CPI. In fact, under the gmm the estimated elasticity of the CPI with respect to e is not statistically significant. Lastly, the elasticity of the CPI with respect to the ULC for the United States is equal to 1.03, that is, a value within the range of the estimations for the panel. Second, the error correction term is statistically significant for each country, yet its simple average is very different from both the one estimated by the bta cointegration methodology and the average estimated by the gmm. Given these results, it can be argued that in the long-run the CPI follows the behaviour specified in equation [4], with or without the effect of e. What is more, the adjustment of the CPI to its long-run equation is verified for the United States as well.

As for the estimations for the it period, the following characteristics were found (see Table 5): First, because of data constraints, it was not possible to get a robust estimation for Norway; the estimation for New Zealand was the same as the one reported for the entire period. Second, the ULC is statistically relevant in the determination of the CPI for all the countries for which we were able to run estimations. In contrast, e was not statistically relevant in the determination of the CPI of Mexico, Poland and the United Kingdom. In countries where e is statistically significant, the estimated elasticity of the CPI with respect to e is lower than that with respect to the ULC. For the it period, even though we included the seven countries in the panel, the simple average of the estimated elasticities of the CPI with respect to e and with respect to the ULC are almost the same as those estimated for the panel using the bta cointegration methodology (0.13 versus 0.12 for the estimated elasticity of the CPI with respect to e, and 1.06 versus 1.10 for the estimated elasticity of the CPI with respect to the ULC). The simple average of the estimated elasticities and those estimated with the bta cointegration methodology are very different from the estimated elasticities obtained with the gmm. We found again that the results support our hypothesis regarding the higher importance of the ULC vis-à-vis e in the determination of the CPI. Third, the simple average of the error correct term for each country is similar to the one estimated with the gmm for the panel, while that estimated with the bta cointegration methodology is very different. In sum, from these three cases we gather that the behaviour of the CPI follows the long-run specification given by equation [4], with or without the effect of e. The same is true of the United States.

Given our estimations, the elasticity of the CPI with respect to the ULC ranges between 0.87 and 1.11 for the entire period and between 0.88 and 1.10 for the it sub-period. These calculations not only support our hypothesis regarding the ULC as the main determinant of the CPI; they also show that if the ULC increases, firms tend to transfer all or almost all of the increment onto consumers’ shoulders.

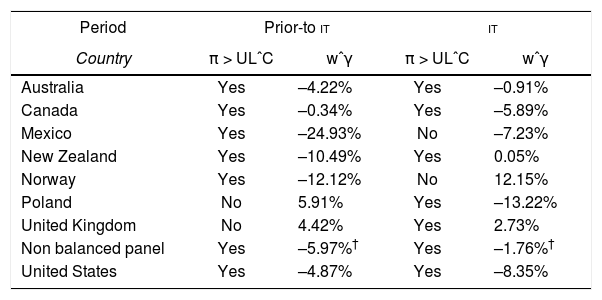

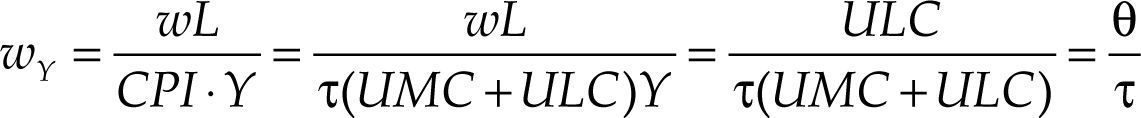

The behaviour of firms affects the functional distribution of income, defined as wγ, w times the number of workers divided by the total value of produced output, expressed as the CPI times γ. So, using equation [3], wY can be expressed as:

Where θ is the proportion of the ULC with respect to the total unit costs. Therefore, the growth rate of wγ is equal to:

Where all variables are expressed in growth rates. Now, reconsidering our econometric results where the main determinant of the CPI is the ULC, we can re-write equation [6] as:

Where π is the inflation rate. According to equation [6]), wγ will increase or decrease if the growth rate of the ULC is higher or lower than the rate of inflation. Table 6 presents the value of wˆγ corresponding to the sub-periods prior-to it and it for every country in our sample and for the entire panel. Since we concluded that the ULC is the main determinant of the CPI, but perhaps not the only one, we compare the value of wˆγ with the behaviour of π relative to the growth rate of the ULC for each country and for the panel.

Percentage variation of employees’ compensation as a percentage of gross value added.

| Period | Prior-to it | it | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | π > ULˆC | wˆγ | π > ULˆC | wˆγ |

| Australia | Yes | –4.22% | Yes | –0.91% |

| Canada | Yes | –0.34% | Yes | –5.89% |

| Mexico | Yes | –24.93% | No | –7.23% |

| New Zealand | Yes | –10.49% | Yes | 0.05% |

| Norway | Yes | –12.12% | No | 12.15% |

| Poland | No | 5.91% | Yes | –13.22% |

| United Kingdom | No | 4.42% | Yes | 2.73% |

| Non balanced panel | Yes | –5.97%† | Yes | –1.76%† |

| United States | Yes | –4.87% | Yes | –8.35% |

As shown in Table 6, when π>ULˆC wˆγ decreases, and vice versa. The empirical exceptions to this postulate happened during the it sub-period in Mexico, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. In Mexico, though ULˆC was higher than π, the difference was almost zero (0.27%). Moreover, from the mid-nineties onwards Mexico's economy came to depend heavily on imported inputs (see Vázquez-Muñoz and Avendaño-Vargas, 2012), implying a change in the structure of total unit costs in favour of UMˆC (i.e., an increase in θ) and, therefore, a decrease in wˆγ. In New Zealand wγ almost remained constant, even though π was higher than ULˆC; New Zealand was the only country exhibiting an appreciation of e, which could have compensated the decrease in wγ. In the United Kingdom, even though π was higher than ULˆCwγ increased, a situation which, in contrast with the Mexican case, could be the consequence of a reduction in θ.

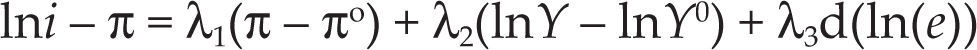

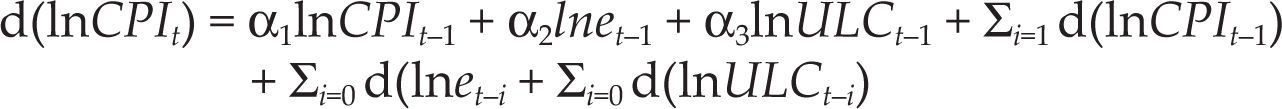

Now, the adoption of the it strategy implies the acceptance of a monetary policy rule for controlling π (the Taylor rule); this rule relates the real interest rate (i – π) with the inflation gap (π – π0) and the output gap (γ – γ0) positively. Bearing in mind our hypothesis and our empirical evidence, the instrument of the monetary policy rule must be related with the components of the ULC, of which the natural candidate is w. In consequence, we estimate the traditional Taylor rule (equation [7]), as well as our implicit monetary policy rule derived from both our hypothesis and the empirical analysis (equation [6]):

Where d(·) expresses the first difference. According to equation [7], the Central Bank increases (reduces) i and, therefore, the real interest rate when π is higher (lower) than π0 and/or when γ is higher (lower) than γ0, and/or when e depreciates (appreciates). On the other hand, according to equation [8], w is the benchmark used to adjust i. Table 7 presents the results of our estimations for the panel corresponding to the entire period and the sub-periods, and for the United States for the entire period. We used the gmm in all cases.

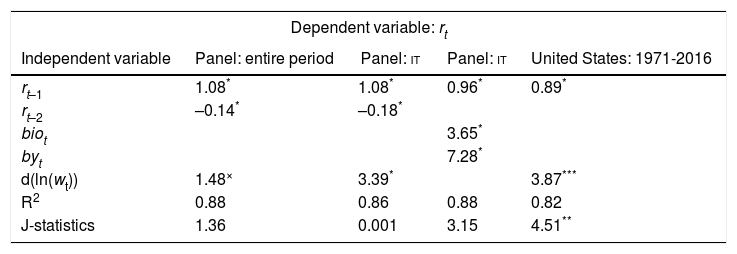

Estimation of the alternative Taylor rules.

| Dependent variable: rt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | Panel: entire period | Panel: it | Panel: it | United States: 1971-2016 |

| rt–1 | 1.08* | 1.08* | 0.96* | 0.89* |

| rt–2 | –0.14* | –0.18* | ||

| biot | 3.65* | |||

| byt | 7.28* | |||

| d(ln(wt)) | 1.48× | 3.39* | 3.87*** | |

| R2 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.82 |

| J-statistics | 1.36 | 0.001 | 3.15 | 4.51** |

Note: Lags of the dependent variable and the independent variables were used as Instruments. The nominal exchange rate was not significant in the estimation of the traditional Taylor rule.

Given the results presented in Table 7, it can be said that: First, e was not relevant in the estimation of the traditional Taylor rule. Second, the panel estimation of the traditional Taylor rule exhibits the expected values of the parameters. Third, the panel estimation of the alternative monetary rule exhibits the expected values of the parameters, both for the entire period and for the it sub-period. Fourth, although it is true that both estimations, the traditional Taylor rule and our alternative monetary policy rule, exhibit the expected values of the parameters, the J-statistics, the Sargan-Hansen test about the over-identifying restrictions of the model, is higher for the case of the traditional Taylor rule than for our alternative monetary policy rule, signalling the latter is a better option. Fifth, if we compare the estimation for the it sub-period with that of the entire period, the elasticity of the real interest rate with respect to w is two times as big in the first case in comparison with the second one, which is indicative of the use of w as the reference variable for changes in the monetary policy instrument, i, especially during the it sub-period. Sixth, the estimation of our alternative monetary policy rule also exhibits the expected values of the parameters for the case of the United States. However, it is not possible to reject the fact that the model is over-identified at the 1% level.

The following reasoning ensues from our empirical results: in order to stabilise π, the ULC must be controlled through reining in w. Firms try to get a higher proportion of total production increasing the mark-up, thus reducing wγ, which in turn implies a reduction of aggregate demand. Such contraction in aggregate demand diminishes inflationary demand pressures1414 Our argument would not be valid if the economies were profit-led (see Marglin y Bhaduri, 1991), however, we consider that there is enough empirical evidence against this possibility (see Piketty, 2014).

Interest-rate rules have become fashionable over the last three decades in advanced and developing economies alike. A new consensus on how to conduct monetary policy has emerged as an increasing number of central banks has adopted inflation-targeting monetary policy frameworks to tackle price instability in a world economy essentially characterized by pure fiat money. The most popular version of such consensus is the well-known Taylor rule where the central bank responds to both inflation gaps and output gaps adjusting the nominal interest rate with the aim of hitting a low inflation target and achieving long-run price stability. The implication is that in it countries the nominal interest rate operates as the anchor of inflation. However, to quote Chesterton (1935-1936: 4/19/30), “fallacies do not cease to be fallacies because they become fashions.”

As discussed above, such new conventional wisdom has not gone unchallenged. Many economists from different theoretical persuasions have shown, on empirical grounds, that the majority of inflation-targeting central banks (if not all of them) often resort to an asymmetric exchange rate policy (chiefly through currency appreciations and sterilised interventions in the foreign exchange markets) aimed at fulfilling their inflation goal. This means that the worldwide price stability observed throughout the so-called Great Moderation period (1982-2007) should be attributed not mainly to the interest rate, but to a large extent to exchange rate appreciations deliberately exacted by the very it central banks, particularly in developing countries. The implication of this criticism is that the exchange rate, rather than the interest rate, is the anchor of inflation in it countries.

Now, if price stability depends on appreciating the exchange rate, then the model as a whole involves a contradictio in adjecto. For in an export-led growth cum inflation targeting macroeconomic model the exchange rate must not be appreciated if tradeable goods are to remain competitive and balance of payments equilibrium is to be preserved. Yet, if the exchange rate does not appreciate in order to spur exports, the inflation target will be missed. The position resembles a Faustian dilemma: As it were, two souls abide within the breast of the it model, and each one seeks for riddance from the other (Goethe, [1808] 2014).

In the present paper we argued that the veritable anchor of inflation is the wage rate, rather than the nominal interest rate or the exchange rate. Our econometric results, based on empirical evidence from a set of it countries, show that cbs have come close to long-run price stability through reining in both the wage rate and unit labour costs. Nonetheless, wage deflation ultimately leads to contractions in aggregate demand, polarization in income distribution and economic stagnation.

La Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act de diciembre de 1989 fue la primera legalización del marco de política monetaria de objetivos de inflación —conocido en inglés como inflation targeting— en la economía mundial moderna. Este modelo de política monetaria, que aspira establecer una meta de inflación baja y estable en el largo plazo, fue adoptado rápidamente por varios bancos centrales del mundo.

Hacia 2002, veintidós países ya lo habían adoptado, es decir, en ese año 10% de las naciones integrantes del Fondo Monetario Internacional (fmi), productoras de más del 20% del producto interno bruto (pib) mundial operaban su política monetaria con un marco de inflation targeting (Truman, 2003). En la actualidad, el número de bancos centrales que practican este enfoque de política monetaria ha crecido tanto (casi suman cuarenta) que se ha convertido en el paradigma monetario dominante, tanto en la teoría monetaria como en la práctica de los bancos centrales (Taylor, 1993; Bernanke et al., 1999). El complemento de este enfoque monetario es un régimen de tipo de cambio flexible o de flotación libre.

El artículo de Perrotini y Vázquez (P&V en adelante) que estamos comentando cuestiona tanto la tesis convencional que afirma que la tasa de interés es el ancla de los precios en el modelo de inflation targeting (it) como la afirmación de algunos autores que observan que las autoridades monetarias controlan la inflación mediante una política cambiaria asimétrica que convierte al tipo de cambio (apreciado) en el ancla de la inflación. Para P&V, la tasa de salarios y los costos laborales unitarios son la verdadera ancla de la inflación.

El artículo explora la interesante y novel hipótesis de que la tasa de salario ha sido el ancla de la inflación en lugar de la tasa de interés nominal o el tipo de cambio, tal y como la literatura ortodoxa lo ha propuesto en el contexto de la llamada regla de Taylor. P&V explican correctamente que la teoría de la tasa de interés como reguladora de los precios no es nueva, había sido planteada por Knut Wicksell, en el siglo xix, en un modelo de oferta de dinero (crédito) endógena, y ahora reaparece como parte esencial de la teoría monetaria de la escuela conocida como Nueva Síntesis Neoclásica o Neo-Wickselliana en su versión más sofisticada, incorporada en el modelo de equilibrio general dinámico estocástico.

La estructura del artículo de P&V se puede resumir en tres partes. La primera es una revisión y discusión del estado del arte de la teoría y la política monetaria de metas de inflación. La segunda muestra que la relación entre la inflación y el crecimiento es distinta para países industrializados o avanzados que para países en desarrollo o de ingresos per cápita menores. La tercera es el análisis empírico realizado para contrastar su hipótesis con información estadística de varios países que practican el marco de política monetaria de metas de inflación.

Sin duda, el trabajo de P&V es una contribución original, demuestra que ni la tasa de interés ni el tipo de cambio son el ancla de la inflación, abre una nueva veta de investigación acerca del papel de la distribución del ingreso en el marco de la política monetaria de metas de inflación, tema hasta ahora prácticamente inexplorado, quizá con la excepción del artículo de Rochon y Setterfield (2008), quienes de todos modos no presentan una contrastación empírica de la influencia de los salarios en la inflación ni relacionan la estabilidad de precios con los costos laborales unitarios.

Aunque la importancia del artículo de P&V para comprender cuál es la variable que permite a los bancos centrales anclar la inflación no está a discusión, puesto que la argumentación de P&V es razonable, conviene plantear algunos puntos que los autores podrían considerar para reflexionar sobre el resultado teórico y empírico de este y de futuros trabajos:

- 1.

Dado que el modelo de objetivos de inflación y la regla de Taylor han desplazado y reemplazado al modelo IS-LM (Hicks, 1937; Romer, 2000), sería interesante que en la parte teórica del artículo P&V expliquen las consecuencias que representa este hecho.

- 2.

La verificación de la hipótesis del artículo de P&V está basada en evidencia empírica robusta sobre la estimación de la ecuación que incluye la tasa de salario en la ecuación de precios con datos de panel dinámico, que usa el estimador gmm, y con la metodología de cointegración. La utilización y comparación de los modelos estimados permite, efectivamente, que los autores puedan probar que existe evidencia confiable con base en pruebas estadísticas que también sugieren que el mejor ajuste está dado por la especificación que incluye la tasa de salario, lo que implicaría que la política de metas de inflación requiere de la deflación salarial para alcanzar el objetivo de la política monetaria. Con la finalidad de asegurar la confiabilidad de los resultados, sería importante que los autores reportaran más información respecto a una mejor descripción de cuáles rezagos de las variables dependientes e independientes fueron utilizados como instrumentos en la estimación con el gmm.

- 3.

Con la misma finalidad de garantizar la confiabilidad de los resultados, convendría que los autores discutieran brevemente la dirección de la causalidad empírica entre las variables y cómo se verificó en las estimaciones.

- 4.

Asimismo, con el propósito de corroborar la confianza en los resultados, sería pertinente que los autores reportaran más información respecto a cómo enfrentar el posible problema de simultaneidad que podría surgir en la forma reducida que representa la ecuación de inflación.

Comentarios sobre estos temas, en el contexto de los modelos en este artículo, fortalecerían los resultados y conducirían a una mejor validación de los hallazgos desde un punto de vista econométrico.

El artículo de Perrotini Hernández y Vázquez Muñóz tiene por objetivo dilucidar la relación existente entre los actuales modelos de política monetaria y la distribución funcional del ingreso como mecanismo para el control del nivel de precios. Más precisamente, la tasa salarial y los costos laborales unitarios (en adelante, clu) se erigen como los instrumentos para la estabilidad de los precios, mas no así el tipo de interés nominal y la tasa nominal de cambio.

Para su propósito, los autores realizan una sucinta, pero detallada, revisión de literatura, donde las aportaciones de Wicksell, la regla de Taylor y la posición de Keynes sobre la inflación, en cuanto producto de la pugna distributiva, toman especial protagonismo. Este último aspecto, dicho sea de paso, es el que inspira el desarrollo de la investigación, por cuanto los clu expresan la relación entre el salario monetario y la productividad aparente del trabajo.

Baste decir a este respecto que casi dos siglos antes de Keynes la economía política clásica tuvo a bien señalar como los reguladores de los precios a los salarios reales y a las condiciones técnicas de producción. Aun cuando Perrotini Hernández y Vázquez Muñóz hacen una breve reseña sobre la importancia que otorgaron los clásicos y Marx a la pugna distributiva en el movimiento de los precios de mercado, resulta conveniente abundar en su legado, a fin de revelar su actualidad para con el problema que analiza el artículo referenciado.

Antecedentes de la hipótesis de investigación. La teoría de los precios de los clásicos y de MarxLa economía política clásica nace a finales del siglo xvii con Pierre de Boisguilbert y William Petty, evoluciona en el siglo xviii con Adam Smith y James Stuart, y culmina con David Ricardo y Karl Marx en el siglo xix. Su inmenso legado queda, empero, opacado por el marginalismo de finales del siglo xix, relegando de esta suerte al ostracismo a la teoría de los precios de Smith (1776), de Ricardo (1818) y de Marx (1894).

En su inmortal obra Principios de economía política y tributación, Ricardo ([1818] 1973, p. 318) hubo de anticipar en más de un siglo a Keynes ([1936] 1964), por cuanto escribe: Lo que regula, en definitiva, el precio de las mercancías es el costo de producción, y no, como se ha dicho frecuentemente, la regulación entre la oferta y la demanda; esta relación puede afectar el valor de mercado de un artículo hasta que sea ofrecido en cantidad mayor o menor, según el aumento o disminución que haya experimentado la demanda, pero esto será sólo un efecto pasajero.

Ricardo ([1818] 1973), como hiciese a la sazón Smith ([1776] 2017), infirió la existencia de unos precios naturales que habían de actuar como los centros de gravitación sobre los cuales habrán de orbitar los precios de mercado en el largo plazo. Marx ([1894] 2006) rebautiza dichos precios naturales como los precios de producción, en la medida en que corresponden a la suma de los costos unitarios de producción más una tasa promedio de rentabilidad.

Vale decir que la proposición de Smith, Ricardo y Marx sobre la existencia de un centro teórico de gravitación de los precios de mercado permitió a Shaikh (1991; 2016) desarrollar su teoría de la ventaja absoluta de costo, según la cual los niveles relativos de los costos laborales unitarios regularán en el largo plazo la dinámica fundamental de los tipos de cambio reales.

Cabe destacar que varias investigaciones muestran suficiente evidencia empírica que apoya la hipótesis de Shaikh con base en la teoría clásico-marxiana de los precios (Antonopoulos, 1999; Martínez-Hernández, 2010; Góchez y Tablas, 2013; Seretis y Tsaliki, 2016; Boundi Chraki, 2017; Tsaliki, Paraskevopoulou y Tsoulfidis, 2017). Para quien escribe estas líneas, el trabajo de Perrotini Hernández y Vázquez Muñóz complementa la tesis de Shaikh, en tanto y en cuanto da un importante paso al revelar que la política monetaria se encuentra subordinada a la lógica de la esfera productiva.

Más concretamente, los autores hacen notar que lo que en apariencia es un fenómeno monetario, es en esencia producto del conflicto que nace en el seno de la esfera de producción. El objetivo de la política monetaria consiste, pues, en garantizar las condiciones de rentabilidad en detrimento de la participación de los salarios en el ingreso nacional.

Como consecuencia necesaria de esto, se observa que los clu, en cuanto centros de gravitación de los precios de mercado, caen tendencialmente a lo largo del periodo 1971-2016. Mas, por otra parte, el índice de precios de consumo de los países estudiados es inferior durante el periodo posterior a la implantación del objetivo de la estabilidad de precios (en adelante it, por sus siglas en inglés) en relación con el periodo previo a su aplicación.

Grosso modo, la estabilidad de precios se encuentra fuertemente correlacionada con el movimiento regresivo de la distribución funcional del ingreso, tanto más cuanto que el proceso de ajuste desde la década de 1980 priorizó la deflación de costos a través de la contención salarial.

La evidencia empírica que obtiene la investigación de Perrotini Hernández y Vázquez Muñóz los lleva a concluir que, en efecto, el salario actúa como el ancla para la estabilización de precios. Ello, vale decir, es un redescubrimiento de Ricardo y de Marx, por cuanto postularon una tendencia decreciente del salario relativo merced a los rendimientos crecientes, el cambio técnico inducido endógenamente por la competencia y el aumento de la productividad laboral.

Comentarios finalesLos autores consiguen responder satisfactoriamente a la pregunta que da título a su trabajo: “Is the wage rate the real anchor of the inflation targeting monetary policy framework?” Esto es, la tasa salarial y los clu son los reguladores de la dinámica fundamental de los precios de mercado. El objetivo de los bancos centrales sobre la estabilidad de precios queda subsumido al imperativo de ajustar una tasa salarial que garantice a las empresas mantener altos sus márgenes de beneficio y bajos sus costos unitarios de producción.

La aparición de nuevos competidores en el concierto del comercio internacional y el descenso de la tasa de rentabilidad que obtienen las empresas de sus nuevas inversiones son factores que, aun no siendo explícitos en el artículo, coadyuvan a comprender la raison d'être de la actual política monetaria con base en la estabilidad de precios.

Por lo anterior, en futuras investigaciones se sugiere a los autores la replicación de su modelo desagregando sectorialmente la muestra. El cálculo de los clu para el conjunto de la economía oculta los impactos del cambio técnico y los rendimientos crecientes en el movimiento de los precios de mercado. Ello es tanto más relevante cuanto que en la actualidad los banqueros centrales se encuentran inmersos en revolver la misteriosa desconexión entre el crecimiento económico y la inflación.

La respuesta a dicho enigma, no vano, conduce nuevamente a redescubrir a los clásicos y a Marx, a saber, los precios de mercado caen tendencialmente merced a la guerra competitiva, el abaratamiento de las condiciones técnicas y los rendimientos crecientes.

Los comentarios de Armando Sánchez y Fahd Boundi a nuestro artículo “Is the wage rate the real anchor of the inflation targeting monetary policy framework?” son edificantes y, además, desafiantes; nos conminan a escrutar ulteriores y más complejas aristas de la nueva veta de investigación que hemos abierto con este artículo. En particular, en lo que concierne a nuestra tesis atinente a que ni la tasa de interés ni el tipo de cambio constituyen la verdadera ancla de la inflación en las economías en las que el modus operandi de la política monetaria de los bancos centrales (bcs) se basa en el modelo de objetivos de inflación (it por sus siglas en inglés): la tasa de salarios y los costos laborales unitarios, sostenemos, fungen como la verdadera ancla de la inflación.

Armando Sánchez destaca cuatro puntos interesantes que nos inducen a las siguientes reflexiones. Primero, ¿cuáles son las implicaciones del hecho de que la regla monetaria de tasas de interés que representa el modelo it ha reemplazado al modelo IS-LM de John Hicks? Principalmente, significa que la curva LM que representa el mercado de dinero ha desaparecido; además, en el modelo IS-LM había espacio para la política fiscal para situaciones en que la economía se encontrara en la región de la trampa de liquidez del famoso diagrama cartesiano de Hicks, correspondiente a niveles muy bajos de la tasa de interés (lo que actualmente se denomina el límite cero de la tasa de interés). En el modelo it, por el contrario, dado que los bcs responden con mayor vigor ante la brecha de inflación que ante la brecha de producto —porque tienen mayor aversión a la inflación que a la recesión productiva—, la única política posible y eficiente es la monetaria, no hay espacio para la política fiscal como instrumento contra-cíclico. Por último, en aras de la brevedad, dado que el modelo it tiene como una de sus premisas fundamentales la hipótesis de la tasa de desempleo no aceleradora de la inflación (nairu por sus siglas en inglés) o una versión nuevo-keynesiana de la curva de Phillips, sólo existe una tasa de desempleo consistente con la estabilidad de precios. Esto significa que no hay lugar para políticas de fine-tuning, es decir, no existe un conflicto (trade-off) entre la inflación y el desempleo.

Segundo, Armando Sánchez nos requiere que reportemos “más información” sobre “los rezagos de las variables dependientes e independientes utilizados como instrumentos en la estimación con el método de momentos generalizado (gmm).” Al respecto, comentamos que la especificación utilizada para estimar la relación de largo plazo dada por la ecuación [4] es:

De la cual, los rezagos utilizados para el periodo completo y para el subperiodo de vigencia del modelo it se determinaron con base en el criterio de información Schwarz. Ahora bien, los instrumentos utilizados en la estimación por el gmm fueron: los rezagos 1 y 2 de la variable d(lnCPIt) (la variable dependiente), las variables lnCPIt–1, lnet–1 y lnULCt–1 y la variable d(lnet) para el periodo completo, y el rezago 1 de la variable d(lnCPIt) (la variable dependiente), las variables lnCPIt–1, lnULCt–1 y los rezagos 0, 1, 2 de la variable d(log(ULCt)).

Tercero, en cuanto a “la dirección de la causalidad empírica entre las variables y cómo se verificó en las estimaciones”, la causalidad se supone del tipo de cambio y los salarios hacia la inflación vía el efecto de ambos en los costos unitarios de producción. También realizamos pruebas de causalidad en el sentido de Granger que permiten confirmar la dirección sugerida por el modelo.

Y cuarto, respecto a la manera en que habría que confrontar “el posible problema de simultaneidad que podría surgir en la forma reducida que representa la ecuación de inflación”, la metodología de momentos generalizados es una forma, aunque no la única, de abordar el problema de la simultaneidad entre las variables que conforman una ecuación a estimar. La simultaneidad también se podría enfrentar con la especificación de la regla de Taylor en el contexto de un modelo de ecuaciones simultáneas cointegrado. Los métodos reportados son similares y es muy probable que los resultados no varíen y sean robustos ante cambios en el tipo de modelo.

Si Armando Sánchez hizo riguroso hincapié en la parte econométrica de nuestro artículo, luego de exponer los conceptos fundamentales del paradigma en cuestión, Fahd Boundi, a su vez, nos invita a una reflexión de alta teoría económica que evoca la teoría clásica de los precios y de la distribución del ingreso. La elocuente observación de Boundi acerca de que nuestro análisis empírico conlleva “un redescubrimiento” de la teoría de los salarios y los precios de David Ricardo y Karl Marx no sólo es encomiable, sino que, además, se enmarca en nuestra visión general de la economía como ciencia: volver la mirada hacia la teoría dinámica de los economistas clásicos Adam Smith, David Ricardo y Karl Marx, a fin de encontrar eslabones en la teoría de los precios de la economía política clásica largamente olvidada y abandonada desde la revolución marginalista decimonónica. El análisis clásico de los precios ha sido relegado “al ostracismo” (dice Boundi). Esto es muy cierto, a pesar de la rehabilitación que de esa teoría hiciera Piero Sraffa en su Introducción a las obras y correspondencia de Ricardo y en su Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities de 1960. En efecto, Sraffa criticó el método marginalista de fijación de precios mediante las curvas de oferta y demanda, elaborado inicialmente por William Stanley Jevons, Karl Menger y Léon Walras y coronado por el marginalista más influyente del mundo anglosajón: Alfred Marshall ([1890] 1920). En sus manuscritos Sraffa habla de “la degeneración del costo y del valor” por parte de la teoría económica marginalista. Este proceso de metamorfosis ((dis) understanding, dice Sraffa), que sustituyó la noción física del costo por un concepto de costo subjetivo, tuvo profundas implicaciones para la teoría del valor y la distribución (cf.Garegnani, 1998; 2004; Kurz y Salvadori, 2005).

Al hacernos eco de la valoración que Boundi hace de nuestro trabajo, hay que decir que Sraffa, siguiendo no sólo a Ricardo, sino sobre todo a William Petty, a la fisiocracia francesa y a Turgot, determina los precios a partir de las condiciones físico-objetivas (costos físicos) de producción; y rechazó la determinación subjetivo-psicológica de la escuela marginalista. El marginalismo neoclásico concibe los precios como costo en términos de sacrificio y esfuerzo; el salario y la tasa de interés son la contraparte de la desutilidad del trabajo y del ahorro (la abstinencia en el consumo). A diferencia de la teoría marginalista neoclásica, los economistas clásicos y Marx no creían que existiera una relación sistemática negativa entre los salarios y el nivel de empleo, de donde automáticamente surgiría una tendencia hacia el pleno empleo conforme disminuyeran los salarios y los costos laborales unitarios.

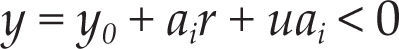

El comentario de Boundi también nos da la pauta para aclarar nuestra posición acerca de la importancia de la tasa de interés en la estrategia de política monetaria del modelo it. Por un lado, como se sabe, la regla de Taylor conlleva de forma implícita, al menos en sus orígenes, un modelo compuesto, entre otras ecuaciones, por la siguiente ecuación de demanda:

donde y es la demanda agregada, y0 es la demanda agregada autónoma, ai mide la sensibilidad de la demanda agregada ante los cambios de la tasa de interés real, r es la tasa de interés real y u es un ruido blanco.Así entonces, por medio de la ecuación [1] podemos analizar la lógica detrás del supuesto efecto desinflacionario de la tasa de interés nominal en el modelo it: se espera que el aumento de la tasa de interés nominal sea tal que a la postre se verifique un aumento de la tasa de interés real, y que con ello se afecte a la demanda agregada a través, al menos, de dos vías: el efecto negativo en la demanda de inversión y el efecto negativo en la demanda de consumo.

De acuerdo con la escuela neoclásica y con Keynes (1936), dada la productividad marginal del capital, un aumento de la tasa de interés real hace más atractiva la demanda de activos alternos a los bienes de capital y, por tanto, desestimula la demanda de inversión. Asimismo, desde el enfoque neoclásico, dada la tasa de sustitución inter-temporal de consumo presente por consumo futuro, un aumento de la tasa de interés real estimula el consumo futuro y el ahorro presente y desestimula la demanda de consumo presente. No obstante, la realidad no parece condecirse con ambos postulados.11 Lo cual no quiere decir que hemos sido capaces de verificar la “productividad marginal del capital” y la “tasa marginal de sustitución de consumo presente por consumo futuro”. Como sostiene Katzner (2006), hay postulados puramente teóricos que por definición no son falsables. No obstante, lo importante es la relación de causalidad que se deriva de ello: a mayor tasa de interés, menor demandas de inversión y de consumo. Es evidente que aquí debemos distinguir entre los cambios inmediatos y los cambios en el tiempo de la tasa de interés real, dado que, como sabemos, la inflación es una variable que reacciona con rezagos. Así entonces, inicialmente un aumento de la tasa de inflación puede verse acompañado de una disminución de la tasa de interés real de forma inmediata y de un aumento de la tasa de interés real en el tiempo.

No obstante, es cierto que en la realidad el banco central utiliza a la tasa de interés nominal como variable de ajuste, y, de hecho, nuestra regla de política monetaria alternativa supone esto mismo. Sin embargo, nos parece que la tasa de interés, más que una variable de ajuste inmediata33 Consideramos que la tasa de interés no actúa de manera inmediata como variable de ajuste, aunque sí lo hace a través del tiempo. Esto se explica de manera sucinta más adelante.

La regla alternativa de política monetaria que hemos encontrado para el conjunto de países que adoptaron el modelo it se puede leer de la siguiente forma: ante un aumento del salario nominal los bcs envían la señal de la necesidad de contraer la demanda agregada para que no haya un aumento de precios. Pero, además, como se ha indicado, la tasa de interés es “una variable distributiva (…) bajo el control del Banco Central” (Rochon, 2018, p. 131). Y es en ese sentido que la tasa de interés sigue manteniendo su papel como variable de ajuste, siendo una “variable distributiva políticamente determinada más que un precio fijado por el mercado” (Eichner, 1987, p. 860, citado en Rochon, 2018, p. 132).

La tasa de interés nominal es una variable distributiva entre las clases sociales de trabajadores y capitalistas industriales, por un lado, y las clases de rentistas (financieros), por otro lado, lo cual, en el mundo actual en el que el sector financiero parece haber confiscado el control de las decisiones de política económica al sector productor industrial, nos parece realista. Además, es otra forma de justificar una reducción del consumo y la inversión ante un aumento de la tasa de interés real, no por medio de los efectos directos en los consumidores y los inversionistas, sino a través de la redistribución del ingreso de los trabajadores e industriales hacia el sector financiero.

Esto último, asimismo, nos da la pauta para indicar lo siguiente: la política monetaria del modelo it ha traído consigo una pérdida de dinamismo de la demanda agregada y en particular de la inversión, lo cual ha contribuido al largo letargo del ritmo de crecimiento de las economías que lo han adoptado. Si bien es cierto que parece haber una redistribución del ingreso de los trabajadores e industriales hacia el sector financiero, los capitalistas del sector real tienen un as bajo la manga, el margen de ganancia, mientras que los trabajadores, en un mundo en el que los sindicatos y el colectivismo cada vez son menos relevantes y el desempleo y/o subempleo se comportan in crescendo, no tienen forma de contrarrestar su pérdida de bienestar en el conflicto distributivo del excedente o producto neto.

Boundi sugiere que “en futuras investigaciones” repliquemos nuestro modelo “desagregando sectorialmente la muestra”, dado que “el cálculo de los clu para el conjunto de la economía oculta los impactos del cambio técnico y los rendimientos crecientes en el movimiento de los precios de mercado.” Es razonable suponer que este ejercicio revelaría efectos heterogéneos del modelo it en los distintos sectores productivos. En particular, puede esperarse que el sector de bienes comerciables acuse impactos diferenciados respecto de los que se observen en el de bienes no comerciables; que el mercado interno haya experimentado consecuencias distintas que el sector externo. La investigación sugerida por Boundi es pertinente también porque permitiría dilucidar el impacto del modelo it en el crecimiento desde el punto de vista del cambio estructural. Sin embargo, creemos que un análisis a nivel mesoeconómico, o incluso microeconómico, no refutaría nuestra hipótesis de que la tasa salarial y los costos laborales unitarios son el ancla de la inflación. Y pensamos, asimismo, que Fahd Boundi coincide con nuestra conjetura.

En términos normativos, la moraleja es que no sólo importa reformar la estrategia de política monetaria, sino que es imperativo que la Banca Central sea una institución más democrática, que represente a los sectores financiero y productivo, al capital y al trabajo, pues ¿acaso la teoría neoclásica no reconoce ya que ambos “factores” forman parte integrante de la función de producción? Después de todo, una distribución del ingreso más equitativa podría redundar en mayores beneficios para los propios capitalistas y acaso también para el sector financiero.44 Tal como reza el apotegma de Michal Kałecki: los trabajadores gastan todo lo que ingresan y los capitalistas ingresan todo lo que gastan (véase Marglin y Bhaduri, 1991).

“There is no such thing in practice as an absolute rule for monetary policy” (Bernanke et al., 1999, p. 5. Italics in the original).