The aim of this paper is to cover the gap in literature about transparency in the context of international trade facilitation. It focuses on the importance of transparency in achieving growth in international trade and the differences between non-transparent practices and corruption in global trade. Managing the disclosure of information about rules, regulations and laws is not the only trade policy instrument where transparency becomes important. To build a framework on levels of transparency we developed a matrix classifying the transparency of each country based on ease of doing business and levels of bribery. Four different strategies are explained based on the different scenarios of transparency in international trade. The main conclusions reflect that disclosure of information is not enough to guarantee transparency and monitoring of transparency must be improved.

El objetivo de este paper es cubrir un hueco en la literatura sobre transparencia en el contexto internacional. Esta investigación se centra en la importancia de la transparencia para alcanzar el crecimiento en el comercio internacional y resaltar las diferencias entre prácticas no transparentes y corrupción. Gestionar la disponibilidad de información sobre procedimientos, regulaciones y leyes, no es la única manera de lograr la transparencia. Para construir un marco con los niveles de transparencia, presentamos una matriz clasificando la transparencia entre los distintos países basado en sus niveles de sobornos y facilidad para hacer negocios. Cuatro diferentes estrategias en comercio internacional son posibles de desarrollar en torno a dicha clasificación. Las principales conclusiones reflejan que la publicación de información no es suficiente para garantizar la transparencia.

In the coming years, all countries will face many challenges in terms of trade facilitation. Customs will be globally networked, customs procedures will be minimized and standardized, burden procedures will be made electronically, and the interoperability among traders will increase enormously. These impending changes are based on the basic principle of transparency in the rules for providing information and the clarity of appeal procedures (customs, national authorities and courts). Researchers have become increasingly interested in ways to reduce corruption; however, there is not a consensus in the definition of transparency. The goal of this paper is to provide insight into transparency in international trade, to develop metrics to measure transparency and provide evidence of the effects of transparency in reducing international trade costs. We introduce a framework that combines well-known Indexes to generate a 2×2 Matrix of Transparency in International Trade to group countries and evaluate potential strategies in International Trade.

Trade facilitation encompasses actions in two main areas: hard and soft infrastructures. The former involves the long-term assets that allow the physical flow of goods, and the latter is concerned with the assets, services and procedures that allow firms to trade internationally. Specifically, trade facilitation is comprised of three main parts. First, trade facilitation includes physical infrastructures such as ports, airports and roads among others. Second, trade facilitation deals with customs and borders administrative processes, transport formalities, tariffs and the application of trade laws and regulations. And third, trade facilitation involves the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) to harmonize and standardize trade procedures among countries and also among all stakeholders involved in international trade (e.g., sellers, buyers, banks, traders, customs, etc.).

Soft infrastructures, especially non-tariff measures, have been considered the most important methods of facilitating trade globally since the Uruguay Round reduced tariff barriers. Today's revolution of international trade is concerned with customs and trade procedures. Now, the main mechanisms for facilitating trade cover transparency, predictability and consistency of procedures, formalities, as well as rules and laws relating to exports and imports. Improving worldwide coordination and cooperation in international trade and related services would reduce the transaction costs, fostering the growth of global transactions.

2Brief history of transparencyTrade facilitation aims to simplify, standardize, harmonize, and make transparent the norms and practices involved in international trade. The goals of transparency have increasingly become the focus of international organizations and multilateral agreements. Key agreements about transparency are close at hand.

Article X of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), published in 1994, stated the commitment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) to improve transparency through its internal and external communication. In this article, the WTO promised to make its operations more transparent through more effective and prompt dissemination of information and improved dialogue with stakeholders. The article also urged all members to publish and disseminate laws, regulations and judicial decisions that could be relevant to trade abroad. The essential implication of the article is that no trade regulation could be applied unless it had been published.

Following GATT, the Doha Ministerial Declaration in 2001 recognized the need for the clarification of three cornerstones of international trade: non-discrimination, transparency, and procedural fairness in interactions between trade and competition policies.

The Revised Kyoto Convention (RKC) of 2006 states that countries wishing to become contracting parties in this convention (as of July 2013 there were 82) must accept the General Annex to the RKC which includes the following principles: (a) transparency and predictability of customs actions; (b) standardization and simplification of the goods declaration and supporting documents; (c) simplified procedures for authorized persons; (d) maximum use of information technology; (e) minimum necessary customs control to ensure compliance with regulations; (f) coordinated interventions with other border agencies; and (g) partnership among members of the supply chain (formal consultative relationships).

More recently, in 2009, the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) approved the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (OECD, 2011). This Recommendation reinforces international understanding and cooperation regarding bribery in international trade transactions. At the same time, transparency has become the minimum standard for accountability in both the public and private sector (Smithe & Smith, 2006). Not coincidentally, transparency can generate accountability (Fox, 2007).

These agreements create a framework for applying transparency in international trade. Hence, transparency can be applied in three ways: trade facilitation, consultation processes, and regulations. Transparency enormously influences the way goods are moved across borders and along the full supply chain. Indeed, transparency has become an essential component of trade facilitation. Furthermore, transparency is vital to the consultation processes among private and public institutions to bring together the strengths of both sectors and increase the efficiencies of international trade. Finally, transparency refers to the elaboration, adoption and implementation of rules and the practices acquainting stakeholders with the relevant measures affecting international trade.

The objective of this paper is to shed light on the study of transparency within the international supply chain, especially in border and “behind-the-border” measures. This paper contributes to an examination of the way those measures, rules, and policies are administered with transparency. While a number of previous studies have examined the broader links between institutions and trade (Smithe & Smith, 2006; Tibana, 2003), our focus is on analyzing in detail the issue of transparency in terms of trade facilitation. This paper adds to the literature by examining new dimensions of the determinants of transparency – namely, the effects of losses; the value of gifts expected in order to secure a government contract; the value of gifts expected to obtain an import license or to get things done; and the amount of documentation, time and expense required to export and import. The framework to be introduced, in the form of a 2×2 matrix that combines the “Doing Business Index” and a “Bribery Index,” allows grouping countries and categorizing them into four groups to get a better understanding of the available strategies for International Trade.

Transparency has a key role in the avoidance of unnecessary trade restrictions. This paper is not focused on how governments can apply a number of non-tariff trade policy measures such as technical standards, trade remedies, and quotas, which all are considered trade barriers. Rather, in this paper we provide an analysis of non-transparent practices, which are also called hidden trade barriers (Helble, Shepherd, & Wilson, 2009). These hidden trade barriers take the form of gifts, irregular payments for exports and imports, and bribes.

Using a cost-benefit approach, it is possible to save some costs from transparency by deploying resources efficiently in customs. But transparency could also involve the entire chain of import-export operations, including not only traders, customs and other regulatory authorities, but also private-sector participants such as banks, customs brokers, insurance companies, freight forwarders and other logistics service providers. It is well known that high trade costs and weak logistics erode international trade business. Conversely, it has been shown that transparency in a business environment significantly increases the flow of international trade (Duval & Utoktham, 2011). The benefits that transparency brings to international trade include: improving trader compliance; easing the logistics procedures; increasing the efficiency and guarding against delays in port inventories and logistic hubs; and speeding up documentary procedures among importers, exporters, traders, freight forwarders, and other logistics providers (e.g., port operators, carriers), which actually reduces trade costs.

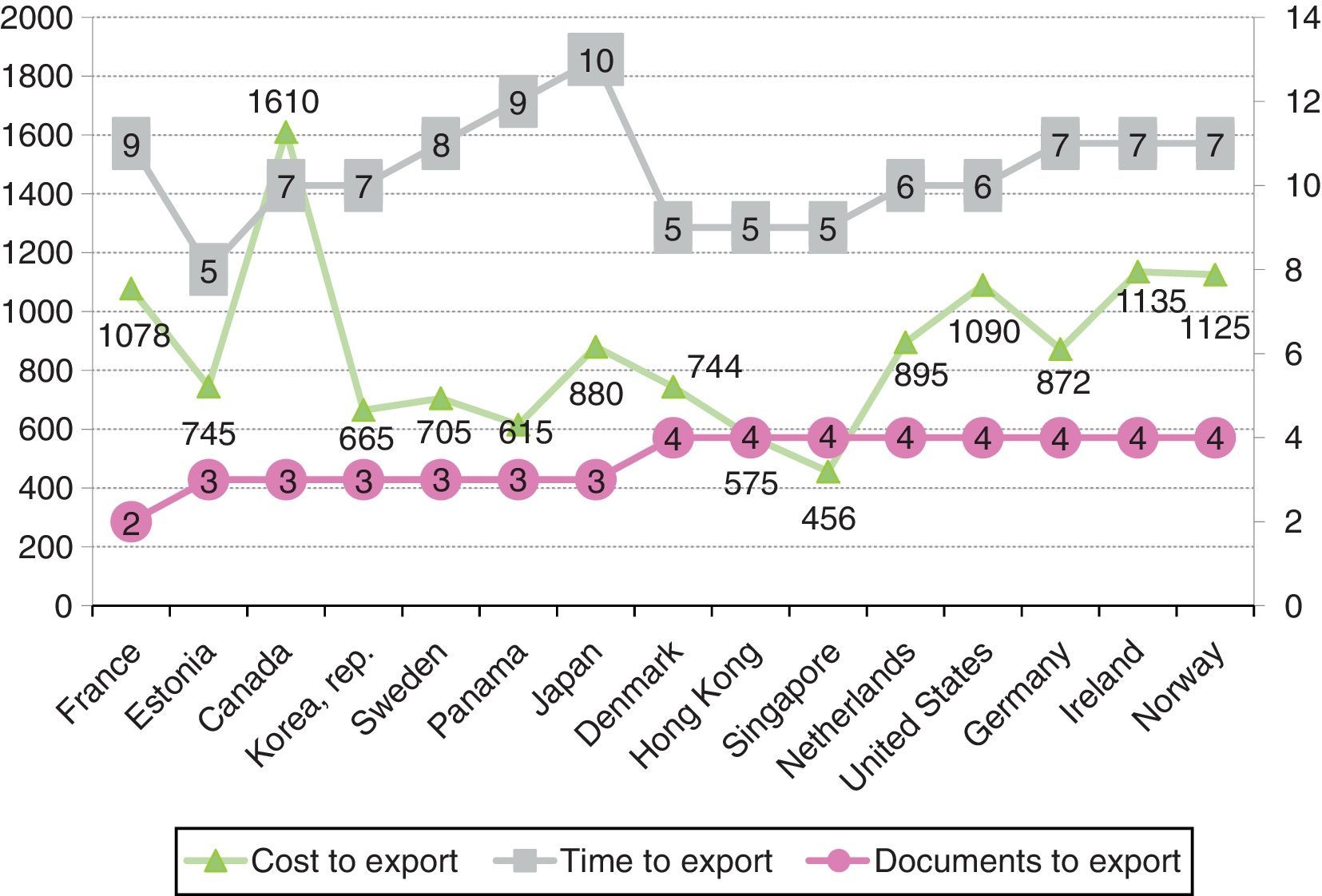

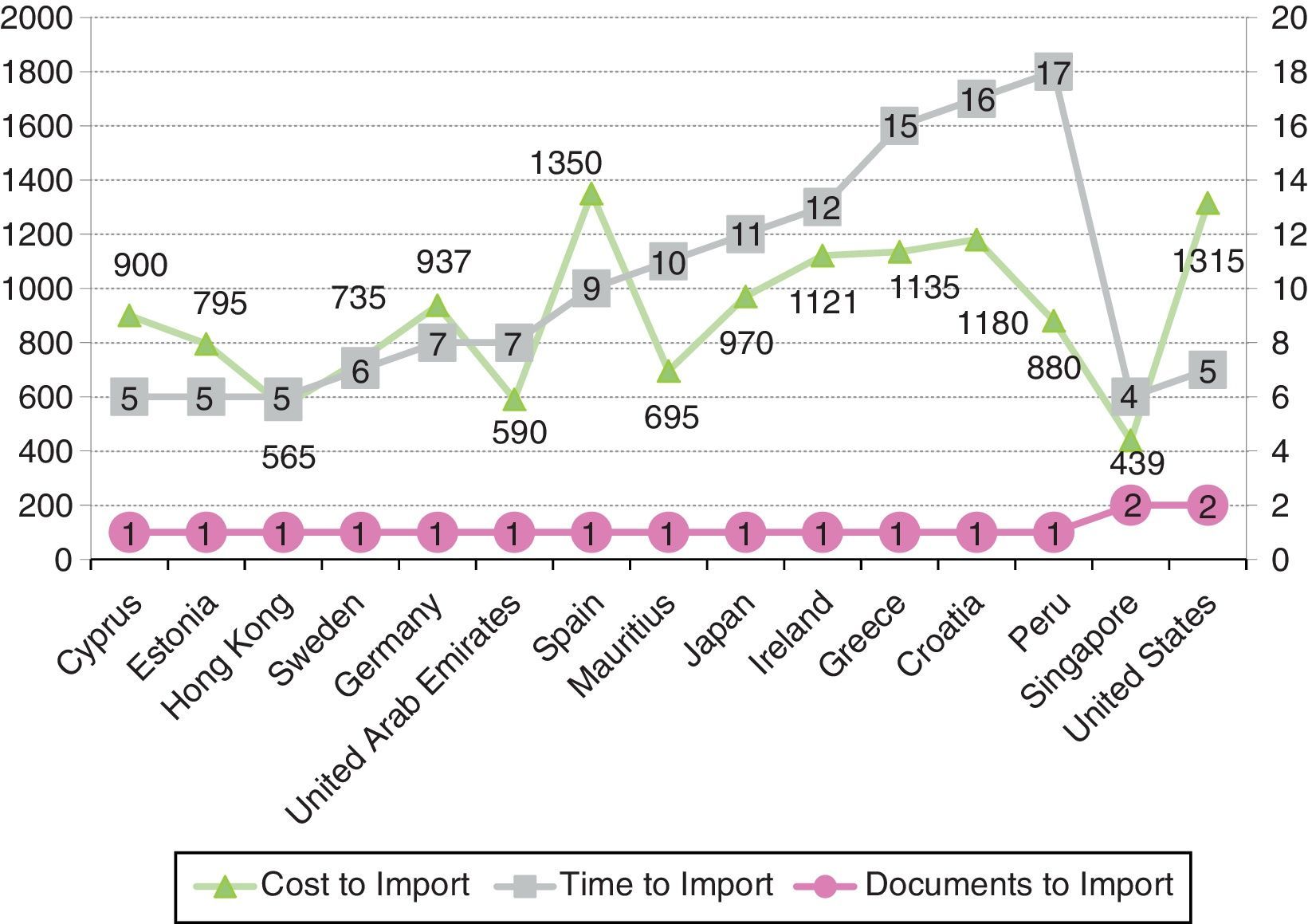

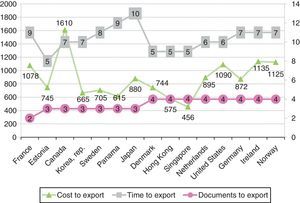

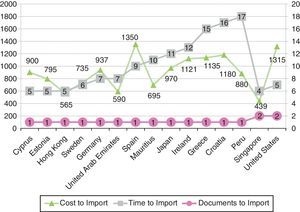

By observing costs, number of documents, and days required to import and export as illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2, it is possible to see less bureaucracy in imports than in exports, in terms of the number of documents required in customs. However, unsurprisingly, the number of days and costs required to import are higher. Both asymmetries give us a sense that there are barriers and protectionism to restrict the free flows of goods and services.

The concept of transparency is sufficiently vague as to lend itself to misinterpretation. Additionally, because it also encompasses a wide variety of components, it is difficult to find a consensus on its definition in the literature in the international trade arena (Atkin, 1999; Halter, de Arruda, & Halter, 2009; Lee, 2012; Nelson, 2003).

Transparency is described as commonly shared knowledge about the economy, its performance, and the way policy influences it (Tibana, 2003). In this sense, it is possible to find conflicting findings about transparency, which may actually hinder conflict resolution, not aid it (Finel & Lord, 1999). These authors measure transparency based on the society's capability to debate ideas and the government's ability to control the flow of information and disclose it to the public. Transparency is crucial to the effectiveness of international flows of goods and services. Indeed, by promoting transparency we are fostering the acquisition, analysis, and dissemination of regular, prompt, accurate and relevant information (Mitchel, 1998). We define transparency in international trade as the fair, open and non-corruptive business and political environment. In this environment, we can make decisions with decisive, accessible, timely and shared information. We believe in information sharing with stakeholders so we may know and control the risks, and protect and execute the rights of every party involved in global trade.

Transparency has two main dimensions: predictability and simplification (Helble et al., 2009; Lejarraga & Shepherd, 2013). Recently, accountability has become another key factor to consider in transparency. Indeed, transparency is considered by Smithe and Smith (2006) as the minimal standard for accountability. In the context of international trade, predictability diminishes the risks to do business abroad. Any unexpected procedure, quota or certificate; any substantial change in the tariff rate applied; any unpredictable aspect, rule, regulation, taxes or laws are all just some examples of non-transparent practices that mean restrictions for trading abroad. Examples of simplification within transparency can include: minimizing the number of documents required to trade; increasing the speed and flexibility of getting import permissions; easing the requirements for compliance to trade abroad; and harmonizing procedures along the trade chain from producers to end clients and through any service providers. Accountability in the context of international trade is about the capacity to execute the right to make the different entities responsible; the capacity to agree warranties in contracts.

The traditional approach to transparency is focused exclusively on the amount of information provided to any third party. Instruments for public access to information generally fall into one of the two categories: proactive and demand-driven. Proactive dissemination refers to information that the government makes public about its activities and performance. Demand-driven access refers to an institutional commitment to respond to citizens’ requests for specific kinds of information or documents which otherwise would not be accessible. Both the dissemination of information and institutional answerability form the concept of transparency. Here is where the accountability goes into action: the formal communication from a public institution or mutual agreements gives rise to duties and rights which include the capability to sanction, compensate, and/or remediate (Fox, 2007). Then, accountability includes the responsibility of taking a political measure or making an agreement.

4Benefits of being transparentHowever transparency is not the panacea. Despite the importance attached to transparency, it remains elusive in practice. In Fox's words (2007), transparency has two different colors: clear and opaque. The distinction between clear and opaque transparency depends on whether the information disclosed reveals or does not reveal how institutions actually behave, in the sense of how they make decisions or what the results of their actions are.

In any possible level of transparency between clear and opaque as extreme sides of the same concept, stakeholders could have conflicts of interests in the economy's role within international trade performance. Unsurprisingly, a descriptive analysis of a survey conducted mainly in Asia concluded that inconsistency and confusion in regulations and their implementation have a significant negative economic impact on international business (Ching, Yuk-Pang, & Zhang, 2004).

Klitgaard (1998) and Silva (1999) argue that the growth of transparency in business combats corruption. Indeed, because the level of transparency is difficult to measure and is a “behind the scenes” factor, corruption works as an indicator of a lack of transparency. Corruption creates barriers that hinder firms from successfully entering new markets. Corruption also reduces the efficiency and the effectiveness of the business process along the international supply chain, from the producer to the end consumer. Often corruption in international trade only refers to the use of public office for private gains. In such cases, an official agent entrusted with carrying out a task by the public (the principal) engages malfeasance for private enrichment, which is difficult to monitor for the principal (Bardhan, 1997). However, it is possible to find corruptive transactions in the private sector too: for instance, shipping goods using an incorrect tariff rate because it is cheaper than the rate that corresponds to the actual goods traded. In terms of trade facilitation, it is possible to find mechanisms to decrease both types of corruption, although corruption in private business is more difficult to detect or to prove (Robertson, Gilley, & Crittenden, 2008).

Avoiding a discussion about what constitutes an immoral practice in a corruptive business environment, some authors argue that corruption improves efficiency and helps growth (Huntington, 1968; Leff, 1964). This perspective explains how corruption can be a viable option when government is too rigid or errs in its decisions, or when the public administration is inefficient. Indeed, bribing strategies should reach a Nash equilibrium by reducing time costs (Lui, 1985) and serving as “lubricants” to a strict bureaucracy (Bardhan, 1997; Lui, 1985). Other models related to bribery are available in the literature (Kleinrock, 1967; Naor, 1969). However we found most literature indicates that corruption and weak government have negative effects on growth and trade (Dutt & Traca, 2010; Mauro, 1995; Rodrik, Subramanian, & Trebbi, 2004). Dutt and Traca (2010) show that when the level of tariffs is high, the impact of corruption displays an inverted U shape in which as long as the level of corruption is low, an increase in corruption expands trade flows and vice versa if the initial level of corruption is high. More specifically, it has been proven that the more a country trades the less corruption level it has (Knack & Azfar, 2003).

Corruption has an increasingly important indirect effect in today's globalized economy, when firms risk a loss of reputation if found trading using corrupt practices in foreign countries. For this reason, firms avoid foreign markets without minimal ethical standards. The exposure to bad publicity might damage the entire firm in each market, with negative effects for the firm in relation to the end consumer. Today's market and the stakeholders have more information about business issues and have the power to moderate corruptive practices. For this reason, corruption plays a key role along the supply chain when trading abroad, because it as an indicator of non-transparent business procedures.

Transparency International (2010) defines corruption as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain. This definition encompasses corrupt practices in both the public and private sectors. Three quarters of the 178 countries on the 2010 Corruption Perception Index score below five on a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 10 (very clean). This index is made up of 13 surveys and assessments, compiling questions relating to the bribery of public officials, kickbacks in public procurement, embezzlement of public funds and the strength and effectiveness of public sector anti-corruption efforts (Rircart, Enright, Ghemawat, Hart, & Khanna, 2004). Although this index is not measuring transparency in international trade, it is useful to rank countries in corruptive practices. Ching et al. (2004) measure the transparency of trade regulation in terms of inconsistency, confusion in implementation and the lack of publicity of regulations.

The continuing and increasing importance of transparency for international trade is reported in many studies using a wide variety of approaches. For instance, Broll and Eckwert's (2006) paper states that the information available on policy variables involves less uncertainty in the exchange rate. These authors modeled how increased transparency in the foreign exchange market affects the export volume of an international firm.

Most studies explore how the availability of information and the increased transparency help to minimize transportation costs (Håkanson & Dow, 2012) and/or increase profit margins (Francois & Manchin, 2007). Government and public institutions play a key role in transparency in the international trade arena by engaging in a broad range of official activities related to customs controls and trade. Institutions support trade by providing information and developing procedures related to import, export and transit, and by issuing provisions related to transportation, official documentation, contract enforcement, property rights, commercial practices and the use of international standards in trade procedures. In this context, many studies underscore the importance of institutions in trade. Anderson and Marcouiller (2002) found that weak institutions act as significant barriers to trade internationally. Levchenko (2007) proved that a high and similar institutional quality in exporting countries increases bilateral trade flows.

5Ease of doing businessFrom the perspective of international trade, the ease of doing business refers to the cost, time and procedures necessary for starting a business, obtaining construction permits, registering properties, getting credits, protecting investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts, employing workers and accessing electricity and water. All these factors comprise the Doing Business Index, which considers the aspects of business that matter to firms and investors or affect the competitiveness of an economy (World Bank and International Finance Corporation, 2013, 2014).

A fundamental premise of the Doing Business Index Report is that economic activity requires good rules: rules that establish and clarify property rights, reduce the cost of resolving disputes, increase the predictability of economic interactions and provide contractual partners with certainty and protection against abuse. These regulations are designed to be efficient, accessible and simple in their implementation (World Bank and International Finance Corporation, 2013, 2014). Firms that want to trade abroad will be exposed to potential challenges, necessitating a superior business climate to reach end consumers successfully. That business climate is supported by two basic pillars: legal framework and efficiency of procedures.

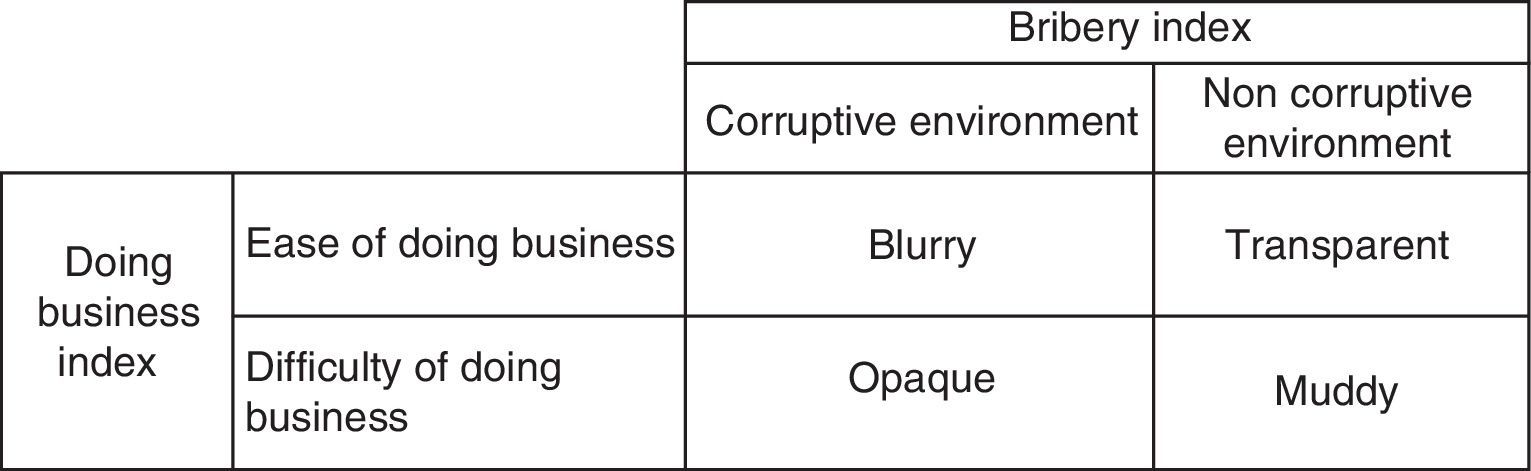

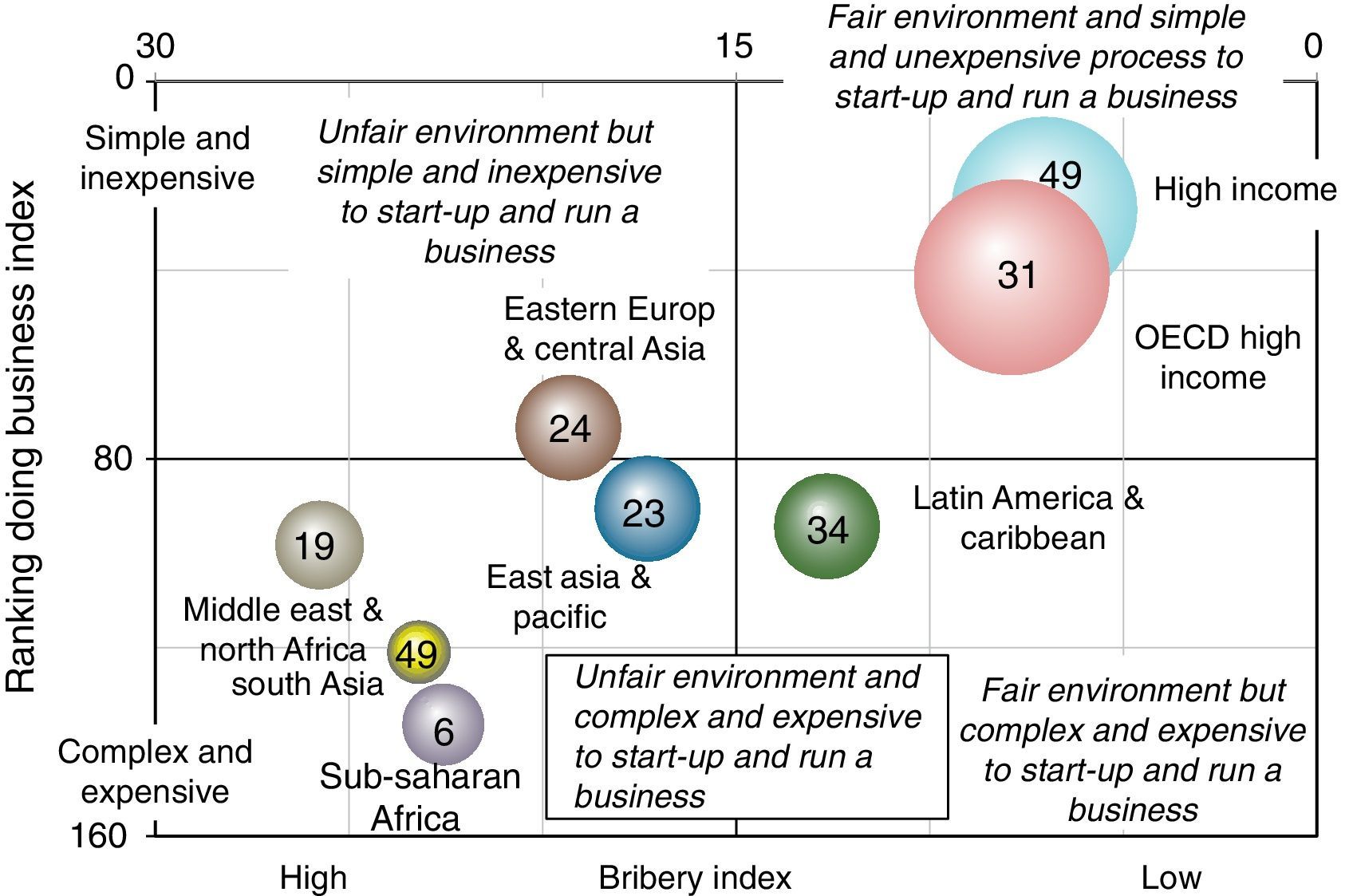

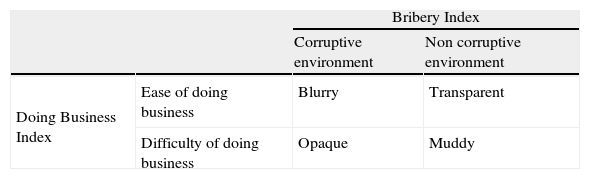

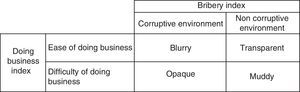

6The transparent scenariosBy combining the concepts of ease of doing business with corruption we can develop the concept of transparency that helps companies allocate resources to deal with different international business environments. The Matrix of Transparency in International Trade is the framework proposed to evaluate countries on the basis of their relative bribery rate and the ease of doing business index (Table 1).

In the Matrix, Doing Business Index refers to the average ranking on getting credit, protecting investors, enforcing contracts, resolving insolvency, employment workers, starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, paying taxes, and trading across borders.

Bribery Index measures perceptions of corruption in the public sector and refers to share average of firms expected to give gifts to public officials “to get things done”, percent of firms expected to give gifts in meetings with tax officials, percent of firms expected to give gifts to secure government contract, value of gift expected to secure a government contract, percent of firms expected to give gifts to get an operating license, percent of firms expected to give gifts to get an import license, percent of firms expected to give gifts to get a construction permit, percent of firms expected to give gifts to get an electrical connection, percent of firms expected to give gifts to get a water connection, percent of firms experiencing at least one bribe payment request, percent of firms identifying corruption as a major constraint, and percent of firms identifying the courts system as a major constraint.

From the matrix we determine four quadrants into which countries can be classified: transparent, muddy, opaque, and/or blurry.

6.1Transparent quadrantTransparent environments are countries highly ranked in ease of doing business and low levels of briberies. Here, the procedures to start up and run a business are well known and easily accomplishable. These countries offer simple customs procedures and a wide access to credit. These countries also have a stable and favorable legal framework for firms and provide to entrepreneurs fast and inexpensive legal instruments protecting them from infringements. Their openness to trade is due to fair rules consistently applied without briberies, gifts or illegal commissions. Transparent environments offer the minimum risks to trade: the rules and procedures in these countries are simple, inexpensive and fast with fair and incorruptible regulatory regimes. Additionally, we find a high level of competition for countries in this quadrant.

6.2Muddy quadrantMuddy environments are countries ranked low in ease of doing business and with low levels of bribery. In these countries, highly bureaucratic processes to get licenses and permissions act as a barrier to doing business efficiently. In general, they have outdated and complicated procedures that make running or trading with a business slow and expensive. Usually, firms have difficulties getting these governments to disclose accurate information that directly affects their business there. Also, these countries often have unified and non-standardized trade and custom procedures, along with high government levies. Despite the ineffectiveness of their bureaucratic systems, these countries have strong governments with strict mechanisms to protect business against corruption. Thus, in muddy environments we can calculate and determine risk in advance because of the unwavering legal framework, even if the procedures are slow, inefficient and costly.

6.3Opaque quadrantOpaque environments are countries ranked low in ease of doing business and with high levels of bribery. Bureaucracy and corruption are the two major difficulties in doing business in these countries. They have not yet developed the laws, regulations and formalities needed to encourage economic growth. Regulations are complex and inefficient; much time and many documents are needed for trade and the cost of doing business is high. Overly complicated rules and excessive documentation create opportunities for corruption, which is sometimes rampant. Firms are asked to provide gifts to get import licenses and to provide commissions and bribes in exchange for approvals or permissions. The barriers of inefficiency and corruption create the environment with the highest risk for firms operating in these countries. The procedures and rules are difficult to know, making it difficult for firms to measure risks. And even when firms have measured them, the economic system is so uncertain that the risks become unpredictable and the legal framework does not ensure accountability

6.4Blurry quadrantBlurry environments are countries highly ranked in ease of doing business and with a high level of bribery. In these countries, the availability and accuracy of information make trade possible in the private sector. Additionally, procedures for resolving disputes and terminating partnerships are appropriate, accessible and inexpensive. Despite the openness of these markets, there is a gap between information and knowledge and some discretional practices occur with an impartial administration. These countries usually impose high government levies, have non-harmonized procedures among commercial, financial, logistic and regulatory institutions and use modern technologies insufficiently. Simply put, the public administration is corrupt. Usually the corruption appears to “jump the queue” or to find a shortcut. In summary, the risks are predictable in these countries—however, those risks are high.

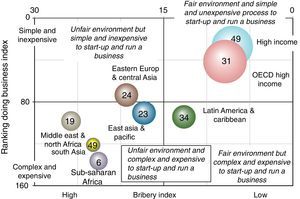

In Fig. 3 we illustrate the application of the Matrix of Transparency in International Trade to the main world economic areas. Notice that the effect of the size of each country is represented by the area of each bubble, calculated by the amount of exports of goods and services divided by Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The Doing Business and Briberies axes cross in the median of both values.

Matrix of Transparency in International Trade by economic areas.

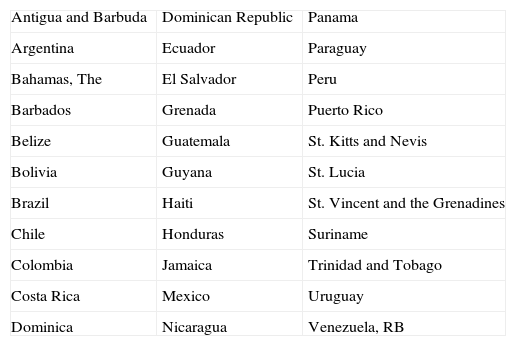

Some conclusions can be drawn from this matrix. First, it is possible to observe that the richest countries are the ones that have the most transparent business environment. Second, the countries that proportionally, as a share of GDP, have less trade internationally are those with the highest level of briberies and the greatest difficulty of doing business. High income and OECD high income countries are the most welcoming and transparent regions to do business, followed by Eastern Europe and Central Asia (the world's second best region for doing business) and Latin America and Caribbean (the world's second non-corruptive environment for doing business). Although there is a clear linear negative relation between ease of doing business and bribery, only when we do an analysis at the country level can we see that the averages obscure big differences among countries within the same economic area.

In Fig. 4 we apply the same methodology as the previous matrix with a non-random sample of countries as examples. The resulting matrix demonstrates the differences in transparency among countries. The trade environments range from transparent (Estonia, Chile, Hungary and Turkey among others) to opaque (Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam). China, Argentina, Bolivia and Brazil have noticeably low levels for ease of doing business, while Kazakhstan, Vietnam and Ghana rank high on the bribery index. This matrix also illustrates the differences among countries belonging to the same economic area, such as Latin America and the Caribbean. In this economic area some countries are spread out across the four quadrants of the matrix.

Matrix of Transparency in International Trade by Country.

The purpose of this matrix is not only to provide a visual way of examining countries as possible destinations for investment or trade. It also allows us to analyze the most suitable strategies to develop in each country based on its doing business and bribery indexes. For instance, transparent environments are recognized for providing the friendliest atmosphere for entrepreneurs, for tackling corruption effectively and for ensuring a sustained commitment to comprehensive changes that boost trade and investment. An appropriate strategy for these countries should be to apply cutting-edge technologies to improve the harmonization of procedures, to apply political reforms that boost business and increase productivity and to create the appropriate climate for dialogue between public institutions and private firms in order to avoid corruption.

Muddy environments are those markets with unclear or ineffective rules, but notwithstanding maintain a low level of corruption. By improving business regulation for entrepreneurs, it is possible to promote greater entrepreneurship, improve productivity and facilitate international trade. By increasing the standardization of procedures and improving the disclosure of information these countries can become more transparent. The weakness of these markets lies in the possibility of corruption if the procedures swell or become very costly or inefficient.

Firms must be cautious of the threats posed in opaque countries, where not only are procedures unclear, but unethical practices present risks in trade and investment. Tackling corruption here requires cooperation and dialogue among stakeholders, a system-wide reform. Auditing institutions should be created or reformed to control the applicability of new clear regulations. In order to substantially improve the economy, governments must create clear rules, disclose timely information, reduce taxes and simplify the bureaucracy to do business. The creation of a business regulatory environment and the standardization of procedures and governability policies are the best strategies to help businesses trust officials, and officials trust businesses.

In blurry environments the rules are sometimes flouted to provide preferential treatment for elites. These markets need governments to invest in institutional structures. The best strategy to apply in blurry countries is to administer auditing policies checking that regulations are applied equally. These countries have to make a firm commitment to detect the proceeds of corruption and then to automate procedures to avoid discretionality. It is remarkable that self-assessment systems reduce the discretionary powers of tax officials and opportunities for corruption. These reforms risk impeding, rather than facilitating, private sector activity. Governments must be careful to continually stimulate business while fighting corruption.

Clearly, performing a more rigorous grouping methodology among regions or countries to analyze commonality elements could expand the applicability and potential normative implications of the Matrix. That is beyond the scope of this paper and material for further research.

7ConclusionsThe increasing importance of transparency should not be taken for granted. Transparency can increase efficiency in the whole logistic chain. It is considered a valuable trade policy tool not only in enhancing the efficient implementation of trade rules, but also in building multilateral trading systems to share information among economic actors.

There are some contradictions in the basic principles of transparency, as with the deployment of information of measures (GATS 1995), in which the enforcement of rules is paradoxical and controversial for the application of non-previously published requirements to trade. In this sense, we believe that current international agreements need clearer rules to establish standardized mechanisms of transparency.

The complex policy environment reflects the growing practice of giving gifts to the public officers. We consider corruption to be part of the non-transparent concept because it aids in the detection and identification of non-transparent practices. Inaccurate information and uncertainties have a systematic impact on business by increasing the risks of international trade. Transparency is a very valuable mechanism with which to reduce volatility, uncertainty, and unpredictability in the global logistic trade chain, which allows then for the reduction of costs and risks in global trade.

The Matrix of Transparency in International Trade shows that there are different levels of transparency in each economic area, and even within the same economic area it is possible to see a wide variety of transparent environments. This Matrix demonstrates the relationship between the opportunity of doing business abroad and the risk of that business based on the uncertainties and discretionality in applying rules and procedures. The four different scenarios show the trade policy implications and the strategies to improve the consistency of policy to create a better environment to attract trade and investments. A normative set of conclusions requires a more rigorous grouping methodology across regions (or countries). In this paper we chose the regions and countries to illustrate the applicability of the framework.

We believe the paper contributes to the literature of Transparency by providing a framework to emphasize global and local fragilities of trading and investing internationally. We conclude that mechanisms need to be established allowing for the review of the administration of measures, rules and procedures relating to trade in order to eliminate restrictions and to ensure their impartial and consistent applicability. The problems of capacity constraints at international organizations are compounded by insufficient domestic capacity to engage in transparent trade monitoring. We do agree with the idea that disclosure and accessibility to information is not enough to ensure transparency (Atkin, 1999; Lee, 2012; Nelson, 2003; Saha, Gounder, & Su, 2012). It is needed to make this information understandable, clear and useful to provide the opportunity to take the right decisions internationally. Also, the participation of stakeholders is needed to reach the cooperation that brings synergies and provide better services, which helps also to bring transparency. Indeed, the true revolution of good governance and transparency, as a tool that reduces corruption, is through the participation processes that influence at the strategic level of any international business.

The development and efficient communication of new trade measures are not sufficient to ensure transparency. Indeed, the most transparent markets are taking the initiative to enhance competition and improve transparency. To be most effective, information can no longer be managed by a handful of agencies, or even a single government. Instead, solutions where transparency plays a key role have been developed to share information among border management agencies, importers, global manufacturers, brokers, and international governments (as with interoperability among Single Windows and the National Strategy for Global Supply Chain Security in United States). Information is crucial for promoting international cooperation and for developing multilateral information systems. The cross-border exchange of electronic information among customs and stakeholders needs a reduction of information asymmetries, along with the streamlining and simplification of business processes.Better institutional frameworks and consultative mechanisms, harmonization and simplification of trade processes are the key mechanisms with which to increase transparency. Future research in these areas is suggested, especially on how transparency of the trading environments can impact international trade.

We thank the editor, the anonymous reviewers, Monica Maxwell-Peagle, Hurry Burson, Diane Garza and Alexandra Vallina and seminar participants at the University of Kansas, Drexel University and George Washington University for their comments, and friends and family for their support.

East Asia & Pacific

Eastern Europe & Central Asia

Latin America & Caribbean

| Antigua and Barbuda | Dominican Republic | Panama |

| Argentina | Ecuador | Paraguay |

| Bahamas, The | El Salvador | Peru |

| Barbados | Grenada | Puerto Rico |

| Belize | Guatemala | St. Kitts and Nevis |

| Bolivia | Guyana | St. Lucia |

| Brazil | Haiti | St. Vincent and the Grenadines |

| Chile | Honduras | Suriname |

| Colombia | Jamaica | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Costa Rica | Mexico | Uruguay |

| Dominica | Nicaragua | Venezuela, RB |

Middle East & North Africa

OECD high income

South Asia

Sub-Saharan Africa

| Angola | Gabon | Nigeria |

| Benin | Gambia, The | Rwanda |

| Botswana | Ghana | Sao Tome and Principe |

| Burkina Faso | Guinea | Senegal |

| Burundi | Guinea-Bissau | Seychelles |

| Cameroon | Kenya | Sierra Leone |

| Cape Verde | Lesotho | South Africa |

| Central African Republic | Liberia | Sudan |

| Chad | Madagascar | Swaziland |

| Comoros | Malawi | Tanzania |

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | Mali | Togo |

| Congo, Rep. | Mauritania | Turkmenistan |

| Cote d’Ivoire | Mauritius | Uganda |

| Equatorial Guinea | Mozambique | Zambia |

| Eritrea | Namibia | Zimbabwe |

| Ethiopia | Niger |

High Income Countries

| Australia | Greece | Portugal |

| Austria | Hong Kong SAR, China | Puerto Rico |

| Bahamas, The | Hungary | Qatar |

| Bahrain | Iceland | Saudi Arabia |

| Barbados | Ireland | Singapore |

| Belgium | Israel | Slovak Republic |

| Brunei Darussalam | Italy | Slovenia |

| Canada | Japan | Spain |

| Croatia | Korea, Rep. | St. Kitts and Nevis |

| Cyprus | Kuwait | Sweden |

| Czech Republic | Luxembourg | Switzerland |

| Denmark | Malta | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Equatorial Guinea | Netherlands | United Arab Emirates |

| Estonia | New Zealand | United Kingdom |

| Finland | Norway | United States |

| France | Oman | |

| Germany | Poland |