Store brands account for 41% of the Spanish market share in 2011, and a further increase is expected in next years due to economic crisis, which makes up an increasingly competitive market with great research interest. In this context, our study aims to analyze which variables have a relevant influence on store Brand Equity from the consumers’ standpoint in the current downturn context, providing an empirical research on the Spanish large retailing. We carried out an on-line questionnaire to customers of store brands residing in Spain, obtaining a total amount of 362 valid responses regarding the Spanish large retailers Mercadona, Dia, Eroski, Carrefour and El Corte Inglés. Then, the analysis was performed by Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Results obtained suggest that store commercial image has the higher influence on both store brand perceived quality and store brand awareness, and in relation with the sources of store Brand Equity, the dimension store brand awareness shows the greater influence on the formation of store Brand Equity. This study is of great interest for large retailers who wish to increase their store brands’ value proposition to the marketplace, especially during economic downturns.

Las marcas del distribuidor suponen el 41 por ciento de la cuota de mercado em España en el año 2011, y se espera un incremento mayor en los próximos años debido a la crisis económica, lo que configura un mercado cada vez más competitivo com gran interés para la investigación. En este contexto, nuestro trabajo trata de analizar qué variables tienen una influencia relevante en el valor de las marcas del distribuidor desde el punto de vista de los consumidores en el contexto de la actual recesión económica, ofreciendo un estudio empírico para la gran distribución española. Para ello se realizó un cuestionario electrónico dirigido a los consumidores de marcas del distribuidor residentes en España, obteniendo un total de 362 respuestas válidas y considerando a los grandes distribuidores Mercadona, Dia, Eroski, Carrefour y El Corte Inglés. A continuación, se realizó un análisis empleando un Modelo de Ecuaciones Estructurales (SEM). Los resultados obtenidos sugieren que la imagen comercial de la enseña es la variable con mayor influencia sobre la calidad percibida de la marca del distribuidor, como sobre la notoriedad de la marca del distribuidor; y en relación a las fuentes del valor de las marcas del distribuidor, la dimensión notoriedad de marca muestra la mayor influencia en la formación del valor de las marcas del distribuidor. Este trabajo es de gran interés para la gran distribución que desea incrementar la proposición de valor de sus marcas en el mercado, especialmente durante períodos de recesión económica.

An important and recent trend in the retail industry has been the great growth of store brands, especially among non-durable consumer goods. Spain has become one of the European countries with higher increase in store brands market share (Bigné, Borredá & Miquel, 2013). From 2007, with the onset of recession store brands have experienced a steadily increase in their market share, accounting for the 41% of the Spanish marketplace (Symphony IRI consultancy, 2011). In late 2007, Spanish retailers began to feel the effect of the global financial and economic crisis, which in year 2012 continues affecting the retailing and the business environment. The key point is that customers want to keep buying the same products, with the same level of quality, despite having a smaller budget. In this scenario, the competitive positioning of store brands is based on a good value for money, regardless of who is the manufacturer (Amat & Valls, 2010). Moreover, consumers not only are more prone to buy store brands during economic crisis, but also many of them once they tried a store brand, keep on buying them even when the economic downturn is over (Lamey, Deleersnyder, Dekimpe & Steenkamp, 2007).

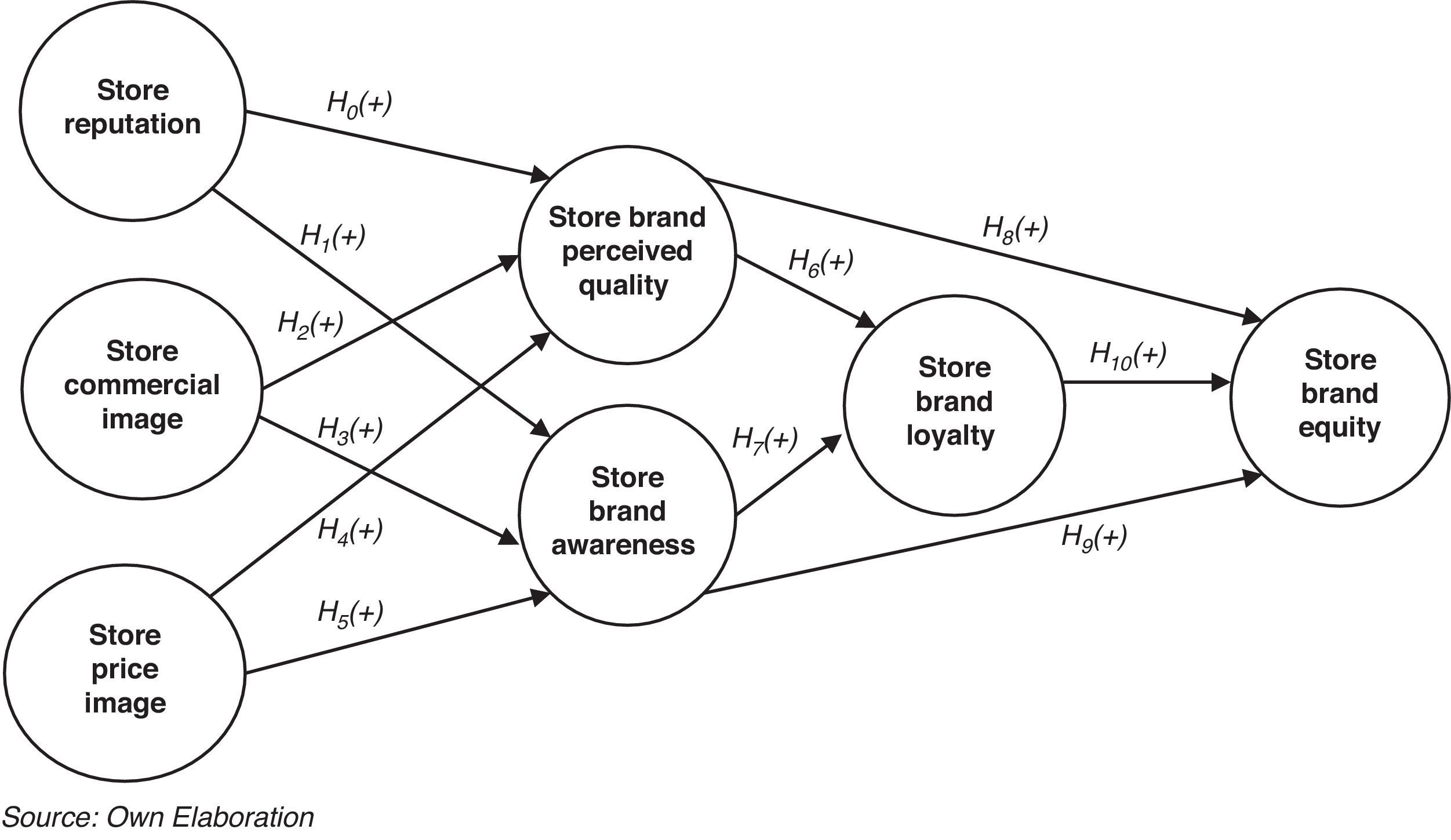

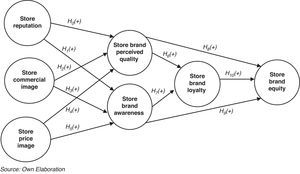

Store brands accordingly have generated significant research interest. Early studies focused on the determinants of store brands’ performance compared to manufacturer's brands (Dhar & Hoch, 1997). A particularly important research line considers the usage of differentiation tools in retailing in order to engender and enhance consumer loyalty (Corstjens & Lal, 2000; Sudhir & Talukdar, 2004). Nevertheless, there are not many studies analyzing the customer-based store Brand Equity and far less within a context of economic downturn. Based on a review of the literature on store brands, the concept of Brand Equity and its antecedents, we present an empirical study of store Brand Equity focusing in the Spanish large retailing in a downturn context, since the study and data were collected in year 2012. This research aims to gain a better understanding of the extent through which store brands generate value to customers – further than a good value for money – as well as these factors which enable an enhancement of store Brand Equity (Figs. 1 and 2).

This paper is organized as follows: in the next section we review relevant previous research and offer some support for our proposed hypotheses and our structural model. We then describe the methodology for our empirical analysis and present and discuss our findings. Finally, we offer the main conclusions and implications, as well as some suggestions for future research.

2Theoretical framework2.1Store brands: concept and characteristicsStore brands, also called private brands, own brands, retailer brands, wholesale brands and distributor's brands have drawn academic and managerial attention, in parallel with their growing market share. Following the definition of store brand or retail brand given by the American Marketing Association, it can be defined as the brand which identifies the goods and services of a retailer and differentiates them from the competitors. In recent years, more retailers carry store brands which have continued to increase their importance, particularly in Europe (Liljander, Polsa & Riel, 2009). Their increasing market share is reinforced with the current trend of retailing concentration, the global economic recession and even with the changing consumer habits (Erdem, Zhao & Valenzuela, 2004). These brands benefit consumers by providing them a competitive alternative to manufacturer brands based on lower prices, due to their lower manufacturing and overhead costs, their less expensive packaging and the lack of advertising (Cunningham, Hardy & Imperia, 1982; Dick, Jain & Richardson, 1995).

Originally, store brands had a clear orientation to price, which is the main motivation for their purchase (Burt, 2000; Kumar & Steenkamp, 2007). However, this initial positioning has evolved to give rise to a varied offer of good value for money (Geyskens, Gielens & Gijsbrechts, 2010; Soberman & Parker, 2006). Nowadays consumers no longer buy store brands exclusively by means of low price – even though this is an important motivation – but because they appreciate their attributes and qualities compared to manufacturer brands. So, the purchase of store brands is not only motivated by the consumers’ orientation to price and their major concern with tight low budgets. Nowadays, store brands are increasingly perceived as products with similar quality comparable to manufacturer brands (Hansen & Singh, 2008; Hansen, Singh & Chintagunta, 2006), derived from the comparable quality of store and manufacturer brands. Although store brands were initially regarded as addressed for price sensitive buyers, their evolution has followed a new strategic approach, based on the importance of the brand, in order to be considered as real brands by consumers (Kapferer, 2008). Morevoer, store brands enable retailers to build a valuable store image and help retailers to compete in the price-sensitive segment (Corstjens & Lal, 2000).

A considerable amount of literature has been published on store brands and variables related to them. Marketing scholars have devoted considerable attention to the variables influencing the purchase of store brands, such as price consciousness (Ailawadi, Neslin & Gedenk, 2001; Baltas, 1997), value and quality perceptions (Bao, Bao & Sheng, 2011; Dick et al., 1995; Liljander et al., 2009), and perceived risk (Liljander et al., 2009; Richardson, Jain & Dick, 1996). Another factors frequently investigated are store image (Bao et al., 2011; Collins-Dodd & Lindley, 2003; Liljander et al., 2009) and socioeconomic profile of store brands customers (Baltas & Argouslidis, 2007; Richardson et al., 1996). However, there is little work about the variables which create and enhance store Brand Equity. It is remarkable the little literature on customer-based store Brand Equity, particularly in a context of economic crisis, which has increased their market share in comparison with the manufacturer brands. Furthermore, most research work on Brand Equity has focused on manufacturer brands instead of store brands (Wulf, Oderkerken-Shröder, Goedertier & Van Ossel, 2005). Our research aims to contribute to this lack of literature regarding store Brand Equity, by providing an empirical study based on the Spanish large retailing.

2.2Store Brand EquitySince a large proportion of most retailers’ revenue and profits come from manufacturer brands, building their own Brand Equity has become a challenging issue for many retailers (Ailawadi & Keller, 2004). A conceptual definition of consumer-based Brand Equity is required in order to develop its dimensions and sources (Keller & Lehmann, 2002). According to Farquhar (1989), Brand Equity could be defined as the added value that a brand gives a product, so store Brand Equity would refer to the added value that a store brand provides to any product from the consumer's viewpoint. Following Aaker (1991), Brand Equity is considered as the set of assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name or symbol, that enhances or decreases the value provided by a product or service to the company and its customers. Keller (1993) defines Brand Equity as the marketing effects or outcomes that accrue to the product or service with its brand name, compared to the outcomes if the same product or service did not have a brand name. Consequently, the store Brand Equity could be defined as the set of assets and liabilities related to the store brand which incorporate or diminish the value provided by the product or service to consumers or to retailers.

The literature contains a substantial number of different approaches to conceptualization of Brand Equity. Aaker (1991, 1996a,b) and Keller (1993) have proposed models for measuring Brand Equity, characterized by the use of different variables related to consumer behavior, perceptions and preferences. Among branding literature, there are a number of papers that highlight the multidimensional nature of Brand Equity (Kim, Knight & Pelton, 2009; Lassar, Mittal & Sharma, 1995), and specially deserve to be mentioned those proposed by Aaker (1991, 1996a,b) and Keller (1993). So, according to Aaker (1991) Brand Equity is conceptualized as a multidimensional concept, which comprises five components, that is, brand awareness, brand loyalty, perceived quality, brand associations or brand image and finally, other assets linked to the brand. Aaker's model has had a greater acceptance in literature (Cobb-Walgren, Ruble & Donthu, 1995; Pappu, Quester & Cooksey, 2005; Yoo & Donthu, 2000). Thus, we propose a model of formation of store Brand Equity being composed by four dimensions – brand associations or brand image, perceived quality, loyalty, and awareness. Moreover, we will consider the model proposed by Yoo, Donthu and Lee (2000), regarding the antecedents of Brand Equity, such as the store image and the store price perception from the consumers’ standpoint. The present paper attempts to analyze the antecedents and sources of store Brand Equity and their influence, considering as store these brands carrying the retailer's name. Given that most of the research work on Brand Equity has focused on manufacturer brands instead of store brands (Wulf et al., 2005), this research aims to contribute to the lack of research on store brands in a downturn context.

2.2.1Antecedents of store Brand EquityFollowing Yoo et al. (2000), the sources or components of Brand Equity can be reinforced by certain marketing activities, highlighting the link between the sources of Brand Equity and its antecedents. According to Kapferer (2008), store brands are subject to two important restrictions, the first one is their positioning based on the store image and the second one is their price – generally set below the price of the leader brands. Previous literature emphasizes three key antecedents of store Brand Equity – the store reputation, store image and store price perception – especially in the case of store brands named like the store or retailer (Collins-Dodd & Lindley, 2003; Semeijn, Van Riel & Ambrosini, 2004; Wulf et al., 2005). Thus, it is interesting to deepen the understanding of the influence of these variables on the sources of store Brand Equity.

2.2.1.1Store reputationIn this study, we define store reputation considering the attributes related to the social and strategic behavior of the store or retailer, provided it may be linked to aspects such as the company's commitment with society (Brown & Dacing, 1997), or to its global corporate strategy (Fombrum & Shanley, 1990) and its strategic planning (Higgins & Bannister, 1992). Therefore, store reputation variable will comprise both the social and the strategic image of the store or retailer. There is a clear linkage between store reputation and the retailer or store brands, since some images and associations that make up the store reputational image, will be transferred to store brands (Mendez, Oubiña & Rozano, 2003). Following Martinez-Leon and Olmedo-Cifuentes (2009), the corporate reputation has great influence in creating and increasing Brand Equity, both for the consumers and the companies. Some authors, such as Semeijn et al. (2004) note that the store or retailer reputation is a direct indicator of the perceived quality of store brands. According to Dick et al. (1995), a better store image – social and overall corporate image – leads to greater perceived quality of store brands. Moreover, the image and associations generated by the store or retailer are positive related to the awareness and familiarity of store brands (Collins-Dodd & Lindley, 2003). Therefore, we pose the following hypothesis.H0 The store reputation has a positive influence on the store brand perceived quality. The store reputation has a positive influence on store brand awareness.

Store image has been extensively studied. Following Thompson and Chen (1998), it can be defined as the attitude derived from the evaluation of the main attributes of the store; whereas other authors, such as Huvé-Nabec (2002), define store image as a set of associations linked to the store in the memory of consumers which creates an impression or an overall image. The store commercial image is considered a multiattribute variable (Bloemer & Ruyter, 1998), and most authors have emphasized functional attributes such as service, product quality, variety, the store atmosphere the, or value for money (Chowdhury, Reardon & Srivastava, 1998; Erdem, Oumlil & Tuncalp, 1999; Jacoby & Mazursky, 1984; Jin & Kim, 2003).

In the present study, store commercial image is defined considering the functional attributes concerning the commercial offer (Barich & Srinivasan, 1993). Therefore, the store commercial image comprises attributes which influence the store overall image: the merchandise layout, the assortment and quality of the products offered, services provided, the type of brands offered, the physical store appearance, the internal atmosphere, the appearance and service of employees, the price level, the depth and frequency of promotions (Lindquist, 1974; Mazursky & Jacoby, 1986). Some authors have stressed the positive relation between the store commercial image and the store brands associations. More specifically, it should be highlighted the influence of the retailer commercial image and the perceived quality of the store brands available (Collins-Dodd & Lindley, 2003). Consumers use certain attributes of the store commercial image, like the quality or the product offer, as well as the store internal atmosphere, in order to assess the quality of store brands (Richardson et al., 1996). Thus, the following initial hypothesis is presented.H2 The store commercial image has a positive influence on store brand perceived quality.

The linkage between store commercial image and store brands awareness is determined by the relationship of the store and the store brands. So, if the consumer perceives the existence of a link between the store brands and the retailer, some recognition and familiarity concerning the store commercial image, will be transferred to the store brands (Mendez et al., 2003). Other authors point out that the commercial image of the store or retailer, may be generalized to the store brands, when they include the store name or logo on the packaging (Collins-Dodd & Lindley, 2003). The associations created by a store are positively related with the associations created by the store brands available in it. Thus, the following research hypothesis is proposed.H3 The store commercial image has a positive influence on store brand awareness.

The price represents the monetary expenditure that the consumers must incur in order to make a purchase (Keller, 1993). Then, price could be defined as the sum of the value that consumers have to exchange for the benefit of possessing or using a product or service (Kotler & Armstrong, 2008). The price image is related to the consumer price reference, which is the subjective price level the consumer uses to assess the prices observed in several products; that is, the price that a consumer expects that a product will have, or the price considered fair or adequate (Fuentes, Luque, Montoro & Cañadas, 2004). Other authors, like Rondan (2004) remark the main relevance of price regarding frequent purchase products. Although retailers charge lower prices for their own brands, it does not mean they are lacking of Brand Equity or do not provide good value (Ailawadi & Keller, 2004).

Following Ailawadi, Pauwels and Steenkamp (2008), store brands low-price positioning derives from the consumers’ perception of store brands as a convenient price option, compared with manufacturer brands. Nevertheless, store brands are not necessarily targeted only at the price-sensitive consumers and a key factor for store brands’ success is their quality, when comparable to manufacturers’ brands (Hoch & Banerji, 1993). Despite the fact that store brand consumers are price sensitive (Ailawadi et al., 2001; Richardson et al., 1996) the most important driver of store brands is their perceived quality (Dhar & Hoch, 1997; Hoch & Banerji, 1993; Sethuraman, 2000).

Regarding the relationship between store price image and store brand perceived quality, it can be stated that price acting as an extrinsic indicator of product quality, so that a lower price may be associated to a lower product quality and vice versa (Rao & Monroe, 1988; Ratchford & Gupta, 1990). Therefore, the store price image, meaning that the retailer or the store offers store brands with affordable prices, available for most of consumers, may positively impact the perceived quality. So that, the following hypothesis is proposed.H4 The perception of an adequate and affordable price has a positive influence on store brands perceived quality.

Finally, in relation to the store price image and the store brand awareness, it should be noted that among the multiple evocations raised by store brands, those linked to the price are clearly positioned. In fact, authors like Aaker (1996a,b) point out that a value proposition of store brands has traditionally been focused on the price. As a result, store brands are perceived as an alternative offer with a better value for money than manufacturer brands. Moreover, price image could give rise and increase store brand awareness, based on the savings obtained in the purchase (Guerrero, Colomer & Guardia, 2000). Lastly, the following research hypothesis is posed.H5 The perception of an adequate and affordable price has a positive influence on store brands awareness.

According to Zeithaml (1988), perceived quality is the overall result of the experience of different stimuli that consumers can use to evaluate the competitive quality of a specific brand or product. Aaker (1991, 1996a,b) conceptualized perceived quality as an intangible overall feeling about a determinate brand, usually based on some underlying dimensions, such as the products’ characteristics attached to a brand like reliability and performance. Perceived quality is a main determinant of store brands’ success (Sprott & Shimp, 2004) and it was found to have substantial exert on purchase intention (Bao et al., 2011). The importance of store brands’ perceived quality, clearly means that the better the store brand is positioned in terms of quality, the more likely is to be purchased (Ailawadi & Keller, 2004). However, previous literature indicates that store brands suffer from a poor low-quality image, which is probably fostered by the widespread use of poor looking packaging, inexpensive packages and a lack of an attractive brand image (Richardson, Jain & Dick, 1994). Perceived quality has a significant positive effect on Brand Equity construct, being the basis for a favorable and positive brand assessment by the consumer (Farquhar, 1989). Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed in our research.H8 Store brand perceived quality has a positive influence on store Brand Equity.

In the present study generates key insights regarding store Brand Equity. On one hand, examines the relationships between the sources of Brand Equity and its formation; and on the other hand, incorporates the possible linkages of perceived quality and brand awareness on brand loyalty, since many authors have suggested the existence of a causal order between these dimensions (Keller & Lehmann, 2002; Yoo & Donthu, 2000). We propose that the image and associations that a consumer has on a brand will result in the development of a brand evaluation – perceived quality – and brand awareness. Subsequently, these assessments will influence on consumer brand loyalty. Thus, we raise the following hypothesis.H6 Store brand perceived quality has a positive influence on store brand loyalty.

The role of the dimension brand awareness in Brand Equity depends on the level of noticeability that is achieved by a brand in the marketplace. The increase of brand awareness will influence the formation of Brand Equity (Aaker, 1996a,b; Keller, 1993; Marshall & Keller, 1999). So, the higher the level of awareness, the more dominant is the brand, increasing the likelihood that this brand is considered in many purchase situations. Thus, enhancing brand awareness increases the probability that a brand will be in the consideration set (Nedungadi, 1990) and will influence the consumers’ purchase decision. Following Dhar and Hoch (1997), having the same brand name and package design for products in a wide array of categories across the store, strengthens the brand awareness and the recall of the store or retail brand and may facilitate the consumer's purchasing decision. Therefore, in our research, we propose the following hypothesis.H9 Brand awareness has a positive influence on store Brand Equity.

There is empirical evidence confirming that store brand loyalty may improve as consumers become more familiar with the store brands. The purchase decision is facilitated by the ability to find a determinate brand across a wide range of product categories (Steenkamp & Dekimpe, 1997). Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.H7 Brand awareness has a positive influence on store brand loyalty.

Brand loyalty arises when the consumer acquires a range of positive perceptions on the brand that will be later transformed into commitment or brand loyalty (Oliver, 1999). Consumers who have generated positive associations to the brand, and perceive it offers a higher quality, have a greater tendency to develop brand loyalty (Pappu et al., 2005). Authors like Yoo et al. (2000) or Atilgan, Aksoy and Akinci (2005), have demonstrated that consumer brand loyalty is one of the key variables that positively influence Brand Equity, because consumers are loyal and show more favorable responses to a brand, than consumers who are not. So, we propose the following hypothesis.H10 Store brand loyalty has a positive influence on store Brand Equity.

The reality of store brands is enormously rich and complex, since store brands are available in several commercial retailing formats (Kapferer, 2008), so it requires the selection of a specific research area in order to test the hypothesis raised. Our research universe comprises Spanish consumers who purchase store brand products in supermarkets, hypermarkets, department stores or discount stores. We followed some criteria in order to select the retailers. First, we selected a number of different retail formats, focusing on the leading companies in the Spanish retailing system, considering their total revenue in year 2011 (Food Retail in Spain, Marketline, 2012). Then, we chose the stores that made available to consumers a store brand which included either the store name or logo on the packaging. This way, we chose Mercadona and Eroski – supermarket format, Carrefour – hypermarket, the retailer Dia – discount store, and finally El Corte Inglés – as department store format. Thus, for the present study we selected five major retailers based on availability and familiarity.

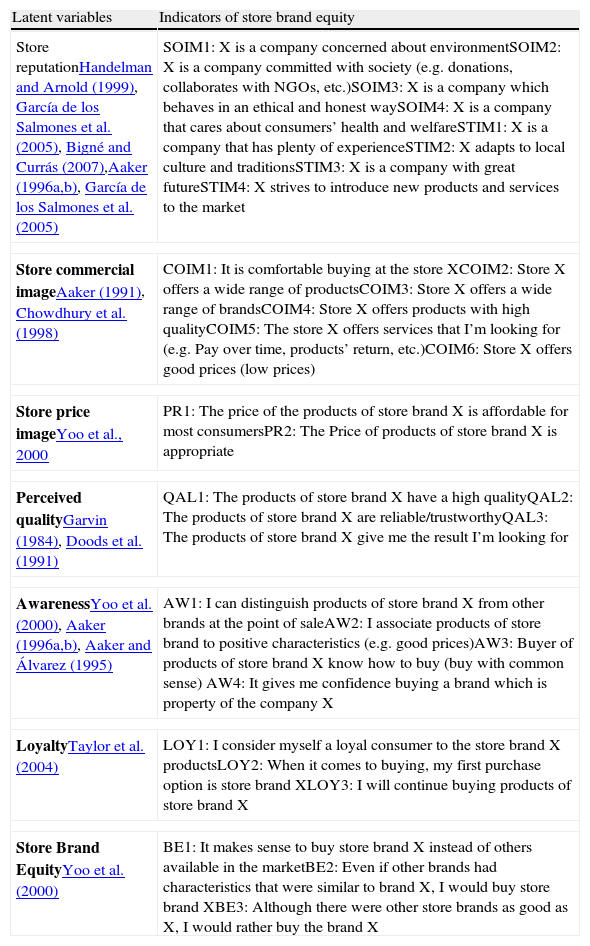

Regarding the variables and indicators selected, we considered previous literature and research on the subject. First, store reputation was evaluated using some items suggested by García de los Salmones, Herrero and Rodríguez del Bosque (2005), taking as a key element the perceptions of consumers about the ethical and social corporate behavior. This way, this study follows the research line about the influence of the corporate social responsibility on consumers’ behavior (Bigné & Currás, 2007; Handelman & Arnold, 1999). In order to measure the strategic image of stores, we used some indicators proposed by Aaker (1996a,b), concerning the company experience on commercial retailing. Moreover, we also included some items proposed by García de los Salmones et al. (2005), regarding the innovation and the future of the retailing companies. The store commercial image was measured by using some items proposed by Chowdhury et al. (1998), to which there has been added one item related to added services offered by the store. Finally, for measuring the second antecedent of Brand Equity – store price image – we used the scale proposed by Yoo et al. (2000), since it considers the price perception from the consumers standpoint. Therefore, we used a scale which aims to measure price affordability for consumers – affordable prices – taking into consideration that a higher value of these items means that consumer perceives price as more affordable and suitable to the household budget.

The sources or dimensions of Brand Equity were also measured following the previous literature. First, the store brand perceived quality was measured using the scale proposed by Doods, Monroe and Grewall (1991), which aims to gather the consumer's overall assessment on the excellence of a product or brand. Additionally, we included an indicator of quality consistency proposed by Garvin (1984). Second, for measuring brand loyalty we used a scale which includes both loyalty behavioral and attitudinal components toward a brand (Taylor, Celuch & Goodwind, 2004). Finally, in order to examine store brand awareness it was considered the model proposed by Aaker (1996a,b), including some indicators proposed by Yoo and Donthu (2000), and one item suggested by Aaker and Álvarez (1995). The indicators used in the study are summarized in Table 1.

Measurement scales, latent variables and reflective indicators used to measure Brand Equity for store brands.

| Latent variables | Indicators of store brand equity |

| Store reputationHandelman and Arnold (1999), García de los Salmones et al. (2005), Bigné and Currás (2007),Aaker (1996a,b), García de los Salmones et al. (2005) | SOIM1: X is a company concerned about environmentSOIM2: X is a company committed with society (e.g. donations, collaborates with NGOs, etc.)SOIM3: X is a company which behaves in an ethical and honest waySOIM4: X is a company that cares about consumers’ health and welfareSTIM1: X is a company that has plenty of experienceSTIM2: X adapts to local culture and traditionsSTIM3: X is a company with great futureSTIM4: X strives to introduce new products and services to the market |

| Store commercial imageAaker (1991), Chowdhury et al. (1998) | COIM1: It is comfortable buying at the store XCOIM2: Store X offers a wide range of productsCOIM3: Store X offers a wide range of brandsCOIM4: Store X offers products with high qualityCOIM5: The store X offers services that I’m looking for (e.g. Pay over time, products’ return, etc.)COIM6: Store X offers good prices (low prices) |

| Store price imageYoo et al., 2000 | PR1: The price of the products of store brand X is affordable for most consumersPR2: The Price of products of store brand X is appropriate |

| Perceived qualityGarvin (1984), Doods et al. (1991) | QAL1: The products of store brand X have a high qualityQAL2: The products of store brand X are reliable/trustworthyQAL3: The products of store brand X give me the result I’m looking for |

| AwarenessYoo et al. (2000), Aaker (1996a,b), Aaker and Álvarez (1995) | AW1: I can distinguish products of store brand X from other brands at the point of saleAW2: I associate products of store brand to positive characteristics (e.g. good prices)AW3: Buyer of products of store brand X know how to buy (buy with common sense) AW4: It gives me confidence buying a brand which is property of the company X |

| LoyaltyTaylor et al. (2004) | LOY1: I consider myself a loyal consumer to the store brand X productsLOY2: When it comes to buying, my first purchase option is store brand XLOY3: I will continue buying products of store brand X |

| Store Brand EquityYoo et al. (2000) | BE1: It makes sense to buy store brand X instead of others available in the marketBE2: Even if other brands had characteristics that were similar to brand X, I would buy store brand XBE3: Although there were other store brands as good as X, I would rather buy the brand X |

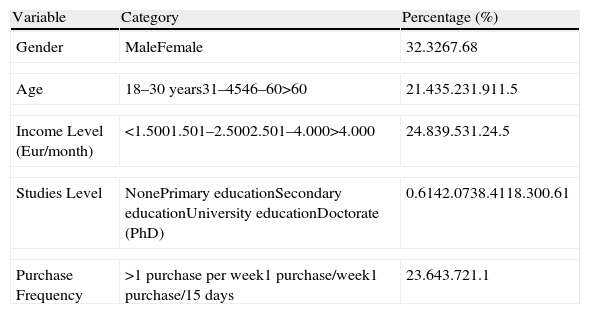

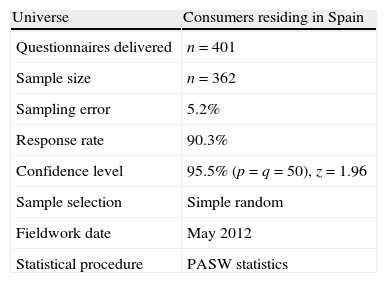

The universe of our study are the consumers residing in Spain. We proceeded with a random sampling among potential consumers of the retailers Mercadona, Día, Eroski, Carrefour and El Corte Inglés. All of these retailers are located and available in Spain. The kind of survey used was the electronic questionnaire and the fieldwork was conducted during the month of May of 2012. A total amount of 401 questionnaires were delivered, whereas 362 questionnaires were returned yielding a response rate of 90.3%. The random error was a 5.2%, assuming the maximun indetermination hypothesis (p=q=50) and a confidence level up to 95.5%. The variables measurement was carried out using a Likert-type scale of 5 points, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 strongly agree. The questionnaire was sent on a random basis, obtaining the following number of valid questionnaires for each store: Mercadona (69), Dia (67), Carrefour (75), Eroski (77) and El Corte Ingles (74). In the provided electronic questionnaire the consumer was requested to assess a meaningful group of items related to the sources and antecedents of store Brand Equity – store reputation, store commercial image, price perception, store brand perceived quality, store brand loyalty and store brand awareness. The final part of the questionnaire collected socio-demographic data of the respondents (Tables 2 and 3).

Sample description.

| Variable | Category | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | MaleFemale | 32.3267.68 |

| Age | 18–30 years31–4546–60>60 | 21.435.231.911.5 |

| Income Level (Eur/month) | <1.5001.501–2.5002.501–4.000>4.000 | 24.839.531.24.5 |

| Studies Level | NonePrimary educationSecondary educationUniversity educationDoctorate (PhD) | 0.6142.0738.4118.300.61 |

| Purchase Frequency | >1 purchase per week1 purchase/week1 purchase/15 days | 23.643.721.1 |

Technical survey sheet.

| Universe | Consumers residing in Spain |

| Questionnaires delivered | n=401 |

| Sample size | n=362 |

| Sampling error | 5.2% |

| Response rate | 90.3% |

| Confidence level | 95.5% (p=q=50), z=1.96 |

| Sample selection | Simple random |

| Fieldwork date | May 2012 |

| Statistical procedure | PASW statistics |

This covariance structural analysis identifies not only the variables that are explained by the different items or indicators, but also the weight or the influence of each one of these factors – antecedents of Brand Equity – to determine the sources of store Brand Equity. For that purpose, we use Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Amos 18.0 was selected for the analysis.

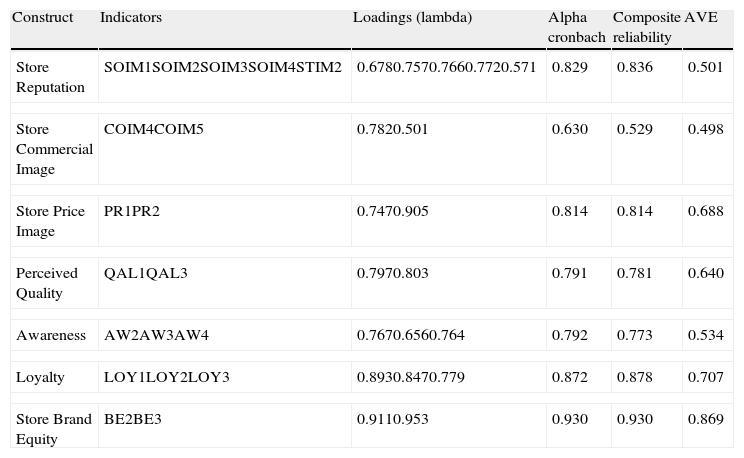

4Results4.1Analysis of the measurement modelPrior to analyzing the relationships amongst variables, we will briefly examine the measurement model. Confirmatory factor analysis was applied to the latent constructs. The first analysis revealed the need to remove several items from the initial scale in order to measure dimensions of store Brand Equity. Therefore, some items from the initial proposed scale were deleted, like some of the items that measure store reputation (STIM1, STIM3, STIM4), store commercial image (COIM1, COIM2, COIM3 and COIM6), perceived quality (QAL2), store brand awareness (AW1) and store Brand Equity (BE1). Having removed these indicators, the results showed an appropriate specification of the proposed factorial structure (Table 4). Regarding the analyses of internal consistency and reliability, Cronbach Alpha, Composite reliability coefficients and analysis of the average variance exceeded (AVE) were calculated. We obtained Cronbach Alpha in order to assess reliability, reaching acceptable values of 0.7 and 0.8 exceeding the threshold of 0.7 usually required (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson & Tatham, 2006), except for variable awareness, which should be analyzed in further research. Following previous literature, Composite reliability coefficients that exceed a value of 0.5 confirm the internal reliability of the construct considered (Bagozzi & Yi, 1989), even though some authors like Lévy-Mangín and Mallou (2006) would require higher values. In relation with the analysis of extracted variance exceeded (AVE) that should exceed the threshold of 0.5 (Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black, 1999), we also obtain acceptable values for all constructs.

Factor loadings of latent variables and indicators of internal consistency and reliability.

| Construct | Indicators | Loadings (lambda) | Alpha cronbach | Composite reliability | AVE |

| Store Reputation | SOIM1SOIM2SOIM3SOIM4STIM2 | 0.6780.7570.7660.7720.571 | 0.829 | 0.836 | 0.501 |

| Store Commercial Image | COIM4COIM5 | 0.7820.501 | 0.630 | 0.529 | 0.498 |

| Store Price Image | PR1PR2 | 0.7470.905 | 0.814 | 0.814 | 0.688 |

| Perceived Quality | QAL1QAL3 | 0.7970.803 | 0.791 | 0.781 | 0.640 |

| Awareness | AW2AW3AW4 | 0.7670.6560.764 | 0.792 | 0.773 | 0.534 |

| Loyalty | LOY1LOY2LOY3 | 0.8930.8470.779 | 0.872 | 0.878 | 0.707 |

| Store Brand Equity | BE2BE3 | 0.9110.953 | 0.930 | 0.930 | 0.869 |

The reliability and validity of the scale and its dimensions were evaluated additionally on the basis of a causal model. For this purpose we evaluated the convergent and discriminant validity of the scale and its dimensions. As shown in Table 4, all of the indicators presented significant standardized lambda coefficients exceeding the threshold of 0.50, reaching values close to 0.7, 0.8, and 0.9. These results verify the convergent validity of the scales (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2006; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Lévy-Mangín, 2001; Steenkamp & Van Trijp, 1991). Similarly, the discriminant validity of the measurement model was also ratified by checking that none of the confidence intervals of the estimated correlations between each pair of dimensions contained the value 1.

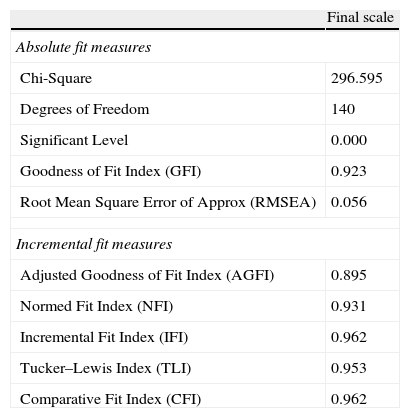

4.2Relations amongst variablesThe overall fit measures indicate that this model can be applied to the store brands of the Spanish large retailing sector. According to results obtained for the structural modeling adjustment, Chi-Square shows a significant value, so it could be considered a reliable indicator of model fit (Bollen, 1989; Hair et al., 1999). Other absolute measures of the modeling adjustment (Goodness of Fit Index and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) show adequate values, given that the former exceeds the 0.9 and the latter comes near a 0.05 value. The measure of incremental fit and parsimony, also indicate a good model fit, considering that the Incremental Fit Index, Tucker-Lewis Index and the Comparative Fit Index show values higher than 0.9 (Hair et al., 1999). Finally, the predictive strength is quite good (R2=0.618). So, the excellent values for the overall fit measures indicate a very good fit of the model to the empirical data (Table 5).

Structural modelling adjustment indexes.

| Final scale | |

| Absolute fit measures | |

| Chi-Square | 296.595 |

| Degrees of Freedom | 140 |

| Significant Level | 0.000 |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.923 |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approx (RMSEA) | 0.056 |

| Incremental fit measures | |

| Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) | 0.895 |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.931 |

| Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | 0.962 |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.953 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.962 |

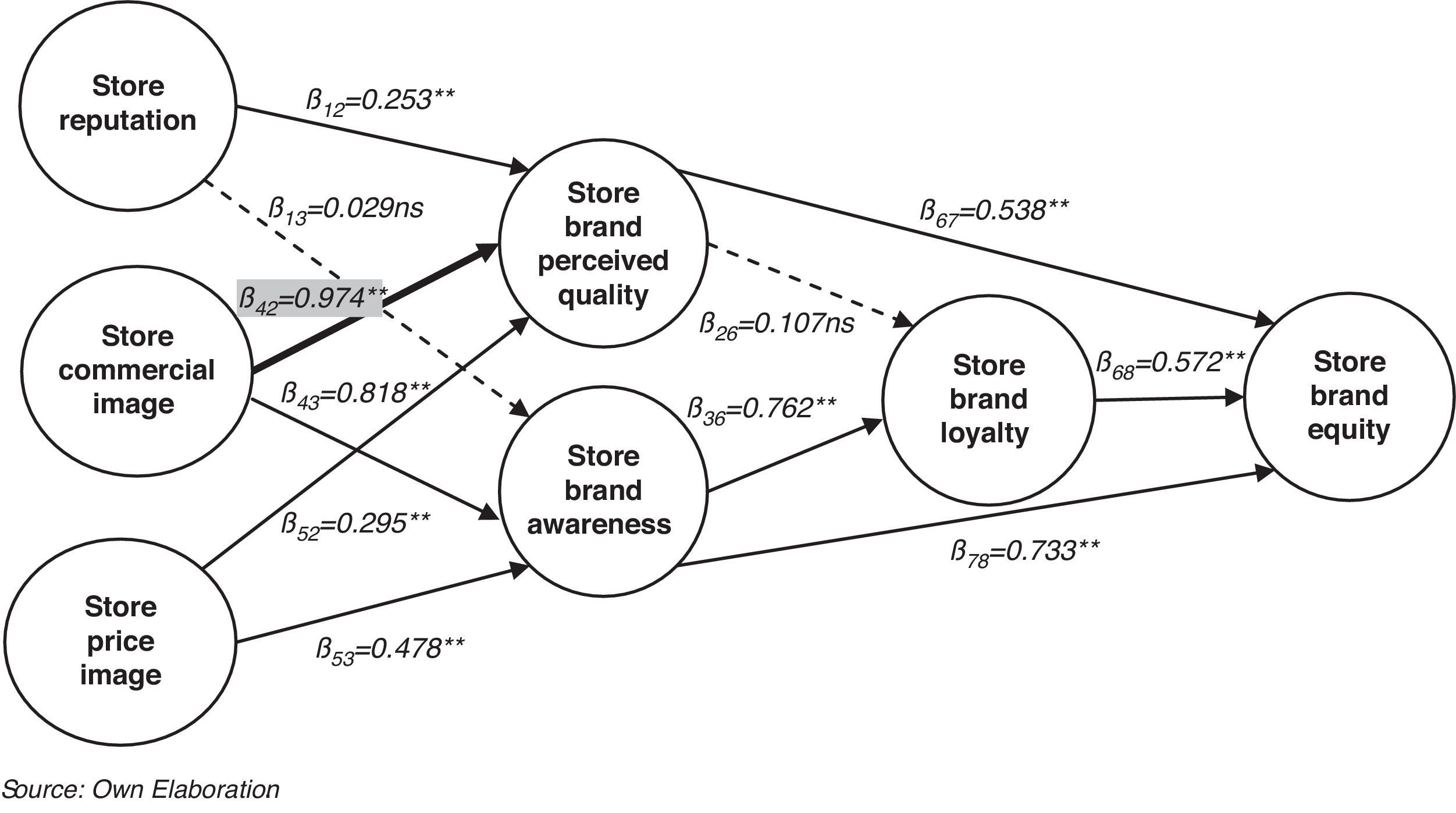

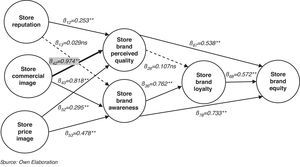

The analysis carried out below will deepen the understanding of the importance of the latent variables considered in our research as antecedents and sources of store Brand Equity. The measures of the model structural adjustment support its acceptable fit to customer-based store Brand Equity. In relation to the structural model coefficients, they all show positive significant values with the exception of store reputation on store brand awareness and store brand perceived quality on store brand loyalty. Our findings support that the antecedents of store Brand Equity have positive significant influence on the sources of Brand Equity – except from store reputation on store brand awareness. Therefore, this research corroborates the initial proposed model (Table 6) and the theoretical framework, by providing empirical evidence about the role of the sources of store Brand Equity.

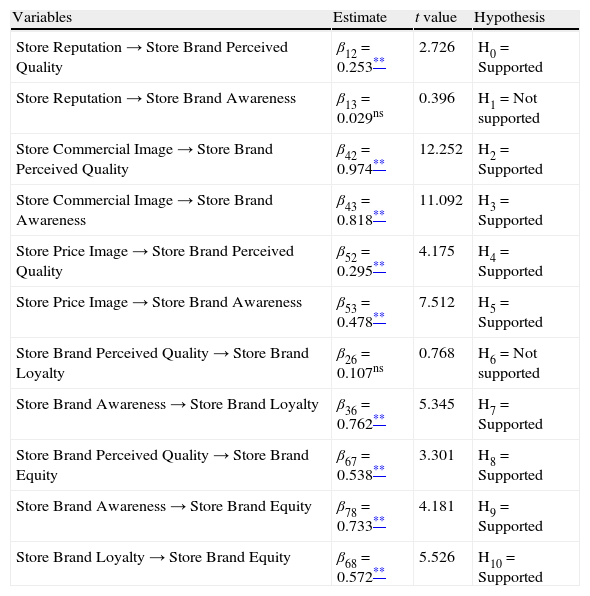

Structural model estimates (antecedents and sources of store Brand Equity, standardized coefficients).

| Variables | Estimate | t value | Hypothesis |

| Store Reputation→Store Brand Perceived Quality | β12=0.253** | 2.726 | H0=Supported |

| Store Reputation→Store Brand Awareness | β13=0.029ns | 0.396 | H1=Not supported |

| Store Commercial Image→Store Brand Perceived Quality | β42=0.974** | 12.252 | H2=Supported |

| Store Commercial Image→Store Brand Awareness | β43=0.818** | 11.092 | H3=Supported |

| Store Price Image→Store Brand Perceived Quality | β52=0.295** | 4.175 | H4=Supported |

| Store Price Image→Store Brand Awareness | β53=0.478** | 7.512 | H5=Supported |

| Store Brand Perceived Quality→Store Brand Loyalty | β26=0.107ns | 0.768 | H6=Not supported |

| Store Brand Awareness→Store Brand Loyalty | β36=0.762** | 5.345 | H7=Supported |

| Store Brand Perceived Quality→Store Brand Equity | β67=0.538** | 3.301 | H8=Supported |

| Store Brand Awareness→Store Brand Equity | β78=0.733** | 4.181 | H9=Supported |

| Store Brand Loyalty→Store Brand Equity | β68=0.572** | 5.526 | H10=Supported |

χ2=296.595, df=140, p=0.000.

R2(Brand Equity)=0.618, R2(Brand Loyalty)=0.748.

ns=not significant.

Comparing the standardized coefficients obtained, the following results must be highlighted. In first place, the hypothesis H1: The store reputation has a positive influence on store brand awareness, is not supported by our empirical research, since this variable showed no statistical significance on Brand Equity. Second, the coefficient which relates store reputation with store brand perceived quality has a positive significant value (β12=0.253**). Therefore, we can conclude that the hypothesis H0: The store reputation has a positive influence on the store brand perceived quality should be accepted. In third place, regarding the initial hypothesis H2: The store commercial image has a positive influence on store brand perceived quality and H3: The store commercial image has a positive influence on store brand awareness, we can state that both of them are supported by our results, provided that store commercial image shows a positive significant influence on perceived quality (β42=0.974**) and awareness (β43=0.818**). So, the better store commercial image – related with the offer of high quality products and the offering of services required by customers – the higher perceived quality, recognition and familiarity with the store brands offered by retailers. Moreover, regarding the antecedent store price image, we may conclude that hypothesis H4: The perception of an adequate and affordable price has a positive influence on store brands perceived quality is supported, since there is a positive significant relation between store price image and perceived quality (β52=0.295**). Thus, we can state that the greater the perception of adequate prices, the higher the store brand perceived quality. Finally, we also find a positive and significant relationship between store price image and store brand awareness (β53=0.478**); thus, the hypothesis H5: The perception of an adequate and affordable price has a positive influence on store brands awareness, should be accepted. Therefore, it should be remarked the main importance of store commercial image as an antecedent of store Brand Equity, stressing its high influence on both perceived quality and brand awareness.

4.3.2Sources of store Brand EquityOne of the major findings of this research is that all relationships of the sources of store Brand Equity and its formation – perceived quality (β67=0.538**), store brand awareness (β78=0.733**) and store brand loyalty (β68=0.572**) – are positive. So, it can be stated that the higher store brand perceived quality, awareness or loyalty, the higher store Brand Equity from the consumer's standpoint. In relation with the sources of store Brand Equity, it should be stressed that store brand awareness is the source with a higher loading (β78=0.733**). In terms of the effect size, the variable store brand awareness seems to contribute the most to the formation of store Brand Equity. Therefore, we can state that the hypothesis H8: Store brand perceived quality has a positive influence on store Brand Equity, is accepted, as well as the initial hypothesis H9: Brand awareness has a positive influence on store Brand Equity, and H10: Store brand Loyalty has a positive influence on store Brand Equity.

As for the relationships among the sources of store Brand Equity, that is, the relationships of store perceived quality and store brand awareness with store brand loyalty, we can state that hypothesis H7: Brand awareness has a positive influence on store brand loyalty, is accepted with a statistical significance level (β36=0.762**). Our findings show that the higher the store brand awareness, the greater store brand loyalty. The explanation for the store brands analyzed – Mercadona, Dia, Carrefour, Eroski and El Corte Inglés – showing a significant brand awareness, may be due to the communication and marketing effort made by all these leading companies in the their own retailing formats within the Spanish market. This would make sense, since El Corte Inglés has the biggest advertising expenditure, followed by Carrefour, and other retailers such as Mercadona or Dia develop the word-to-mouth communication. Nevertheless, regarding the hypothesis H6: Store brand perceived quality has a positive influence on store brand loyalty, we do not find empirical support of its statistical significant effect on store brand loyalty. Our research supports hypothesis H2, H3, that is, that store commercial image along with store brand awareness have a positive relevant influence on store Brand Equity. Furthermore, this research provides support to our initial hypothesis H0, H4 and H5, which means that store reputation and store price image are also important variables to be considered for leveraging store Brand Equity.

In summary, our research poses the question of how relevant is building and enhancing store Brand Equity, stressing the importance of the store commercial image for attaining this purpose. So, Spanish large retailing companies may develop and carry out strategies for managing and increasing store Brand Equity. However, our empirical approach raises the question of whether these results can be generalized to other retailing contexts.

5ConclusionsThere are many articles focused on Brand Equity referring to the manufacturer's brands, and yet there are not numerous articles related to Brand Equity of the store brands. Furthermore, most of the researches on store brands have been posed from the perspective of manufacturers or retailers, whereas in our research we bring in the assessment and standpoint of the consumers, and more particularly of the Spanish consumers. Our findings reveal the multidimensional nature of the Brand Equity construct, which is suitable to store brands, like several previous studies have remarked (Aaker, 1991; Keller, 1993). That is, the performance of store brands depends on the same variables as those of other brands (Jara & Cliquet, 2012). In first place, regarding the antecedents of store Brand Equity, we should highlight the positive effect of the store commercial image and price image – adequate and affordable in a downturn context – on the sources of store Brand Equity. In fact, a number of studies have shown that the store image influences the store brand image (Semeijn et al., 2004), and authors such as Bigné et al. (2013) have proven a direct and reciprocal influence between the store image and the store brand image. More specifically, our results are in line with previous researches, which noted that store image and price perception were considered as the most important antecedents of Brand Equity (Netemeyer et al., 2004). One of the major findings of this research is that store commercial image plays the most important role in the sources of store Brand Equity, which provides useful insights for retailers and marketing managers regarding the effects of store image and associations on consumers (Richardson et al., 1994, 1996). So, as Beristain and Zorrilla (2011) stated in their studies, store image may be used by retailers to influence all components of store Brand Equity, essentially through its commercial image. In terms of managerial implications, retailers should focus their marketing efforts on building and increasing the store commercial image. Moreover, our results suggest that a good and positive store commercial image contributes to the increase of store brand perceived quality, strengthening the efforts undertaken by the retailing companies in order to offer high quality products. Finally, the store commercial image contributes to increase store brand loyalty, so it could be used as a reinforcement of those marketing tools that seek for customers’ loyalty. Consequently, store commercial image influences positively all sources of store Brand Equity and, thus, it may be used for managing and leveraging customer-based store Brand Equity, becoming an important base for store Brand Equity (Ailawadi et al., 2001).

Regarding the second antecedent of Brand Equity, that is, store price image, or more specifically the perception of price as appropriate and affordable to most consumers, our research reveals itself as a variable that influences positively the sources of store Brand Equity. However, contrary to our expectations in times of severe economic crisis and recession, the store price image did not have the highest influence on the sources of store Brand Equity. Price sensitivity is one of the major determinants of consumer preferences for store brands and many authors have showed that consumers are more price-sensitive during economic downturns (Estelami, Lehmann & Holden, 2001). One possible explanation for this result is that the variable to be analyzed is perceived value for money, that is, a good relationship price-quality, instead of an affordable or appropriate price. The question may not be lower or affordable prices, but better value for money. Regarding the store Brand Equity antecedents, our study does not support that store reputation – the store social and strategic image – affects store brand awareness, since there was no significant direct link between these variables. This fact could be explained since the majority of consumers were store brand prone consumers (Dick, Jain & Richardson, 1996).

In summary, in relation with the sources of store Brand Equity, our findings support the Aaker's Brand Equity model, since the initially proposed dimensions – perceived quality, brand awareness and loyalty – have a significant and positive influence on the formation of Brand Equity in Spanish large retailing store brands. Among these dimensions store brand awareness exert the higher influence on the formation of Brand Equity. It can be concluded that consumers are concerned with store brand perceived quality, so managers should create and increase a high quality image to enhance store Brand Equity. Our findings also highlight the importance of brand familiarity and brand loyalty, which play an important role in promoting store Brand Equity. These results are in line with those reported by Jara and Cliquet (2012) who note that both the retail brand awareness and retail perceived quality explain the most significant retail Brand Equity.

Finally, we can state that in a context of economic crisis and tight low budgets, the store commercial image – the offer of high quality products and services required by customers – along with the store price image – the offer of adequate prices – are the most relevant variables in the formation of store Brand Equity from the consumer's viewpoint. In this downturn context, the store brand awareness – the store recognition and familiarity – it is also a key variable to the customer-based store Brand Equity, as well as for the consumers’ loyalty to a specific store brand. Store brands have been traditionally price-oriented in order to attract price-conscious consumers, and this characteristic of store brands might be a critical determinant in the current economic downturn. However and contrary to our expectation, in a context of Economic downturn, this paper shows that store price image – meaning the image that consumers have of a store or point of sale which offers affordable and adequate prices, is not the most important variable to store Brand Equity. Maybe the explanation is that consumers understand and perceive that store brands have a low price per se, since traditionally these brands have targeted the segment of price-sensitive consumers. In a context of Economic crisis which has increased price sensitivity and caused that many families have a shrunk or frozen budget, the commercial store image becomes the factor with the greatest influence on the store Brand Equity. So, as recommended in previous literature (Bao et al., 2011), in order to increase sales of the store brands, retailers should put more emphasis on the store commercial image, as opposed to positioning as a low or affordable price store brand.

Our findings in turn lead to some interesting implications for retail managers and practitioners. The mentioned variables do matter to store Brand Equity and should be managed by retailers and retailing companies, since high-valued store brands give strategic advances and enable the increase of consumers’ store loyalty (Dick et al., 1995), enhancing retailer margins and benefits. More specifically, enhancing store commercial image and store brand awareness has positive significant effects on store Brand Equity, which stresses the importance of configuring and reinforcing marketing activities to increase the store or retailer commercial image and recognition in the marketplace. In summary then, this paper adds to the growing literature in marketing and in store brands, remaining a deeper understanding on how store brands create customer-based Brand Equity, based on an empirical research.

6Limitations and future research guidanceThis study was focused on a particular market, the Spanish large retailing, thus posing serious limitations when extrapolating these results to another countries, territories or even to the retailing industry, given the differences between large and small retailers. Moreover, it should be noted that our research did not consider other forms of commercial retailing, that either have a lower presence in the analyzed territory or do not have store brand, like for example the hard discount. Even though, we understand that the sample size, as well as the incorporation of several formats of commercial retailing, are elements which help reinforce the results obtained, consistent with the previous literature. Further research should compare any significant differences among the four retailing formats explored in this research – supermarkets, hypermarket, discount stores and department stores. As a future research line we aim to continue our research based in other European countries, understanding there might be some regional or cultural differences. In second place, we consider of great interest to analyze store brands whose names are not coincident with the store brand name, in order to find whether the results may suffer variations. Finally, we understand interesting to include the consequences of Brand Equity – such as the intention or the frequency of purchase – in our study, as well as some relevant antecedents – like the perceived risk or the familiarity with store brands (Liljander et al., 2009; Richardson et al., 1996). Although we have made some progress on possible means by which store brands create Brand Equity, much still needs to be done to obtain more insights into the topic.