This paper analyzes the social conditions that produce vulnerability to landslides in two neighborhoods of Teziutlan, Puebla. The goal is to elicit the logic of action that influences vulnerability of these communities, using the concept of risk habitus derived from Bourdieu's theoretical perspective. This framework provides an analytic framework to understand the social logic and every day decision-making processes that relate to risk perceptions and responses of the residents of these landslide-prone settlements. The methods involved the quantitative interpretation of linkages among variables related to residents’ social, cultural and symbolic capitals, which were collected through two complementary surveys. The selected variables focused on previous disaster experiences and social learning, as well as cooperation networks assessment (solidarity between neighbors, trust in local authorities, experience with disaster situations, perception of risk and attachment to place) in each community. The findings show that individuals’ judgments of their own vulnerability are based on their perceptions of preparedness to face a risk situation; it does not matter the actual hazard level to which they are exposed. This relates to their high level of trust in local authorities and the belief that these authorities will help them in a disaster situation. On the other hand, both neighborhoods are certain about suffering future damages in similar conditions than previous disaster events, even though they have very different objective levels of hazard exposure. In both cases, they strongly believe in their capacity or respond to a landslide, despite that neither of them has invested time or resources in preparedness.

Este artículo es un análisis de algunas de las condiciones que reproducen la vulnerabilidad social ante deslizamientos de ladera en dos asentamientos de la ciudad de Teziutlán, Puebla. La propuesta presentada parte del conocimiento de las percepciones, valoraciones y acciones que reproducen condiciones de riesgo a partir de la propuesta conceptual de habitus de riesgo, desde la perspectiva sociológica de Pierre Bourdieu. Este marco conceptual aporta elementos para comprender las lógicas que imperan en los habitantes de los asentamientos de Teziutlán ante situaciones potenciales de riesgo por deslizamientos de ladera. La propuesta que aquí se desarrolla busca interpretar comparativamente las condiciones que reproducen la vulnerabilidad a partir del análisis cuantitativo del capital social, cultural y simbólico (basado en redes familiares, solidaridad entre vecinos, confianza a las autoridades, las experiencias de situaciones de desastres, percepción del riesgo y el tiempo de residencia en la vivienda actual) de las dos comunidades en estudio. Los resultados muestran que las valoraciones sobre el nivel de preparación para enfrentar una situación de riesgo son determinantes para explicar su vulnerabilidad, sin importar el nivel de la exposición a la amenaza al que estén sujetos. Esto se relaciona con el alto nivel de confianza que tienen hacia las autoridades locales, así como la seguridad de que estas autoridades los ayudaran en una situación de desastre. Por otro lado, la población de ambas comunidades manifiesta altas expectativas de que sufrirán daños en condiciones similares si ocurriera un evento de desastre como en el pasado, aun cuando una u otra comunidad tienen distintos niveles de exposición a deslizamientos. En ambos casos, la población cree fuertemente en su capacidad de respuesta ante deslizamientos de ladera, a pesar de que ninguna de las comunidades invierte tiempo o recursos en prevención.

Social vulnerability is an issue that has been addressed by many disciplines and from widely different perspectives (Adger, 1994; Bohle et al., 1994; Cardona, 2003; Eakin and Luers, 2006; Ruiz, 2012). Despite this diversity of explanations and applications to risk reduction research, there is still a lack of studies on the conditions that explain the reproduction of vulnerability in specific geographical and social settings. This paper addresses how social conditions of vulnerability are produced and embodied in different aspects of life of two specific social groups in Teziutlan, Puebla, Mexico, a small city located in the slopes of the Sierra Madre Oriental mountains, with a long history of landslide events.1

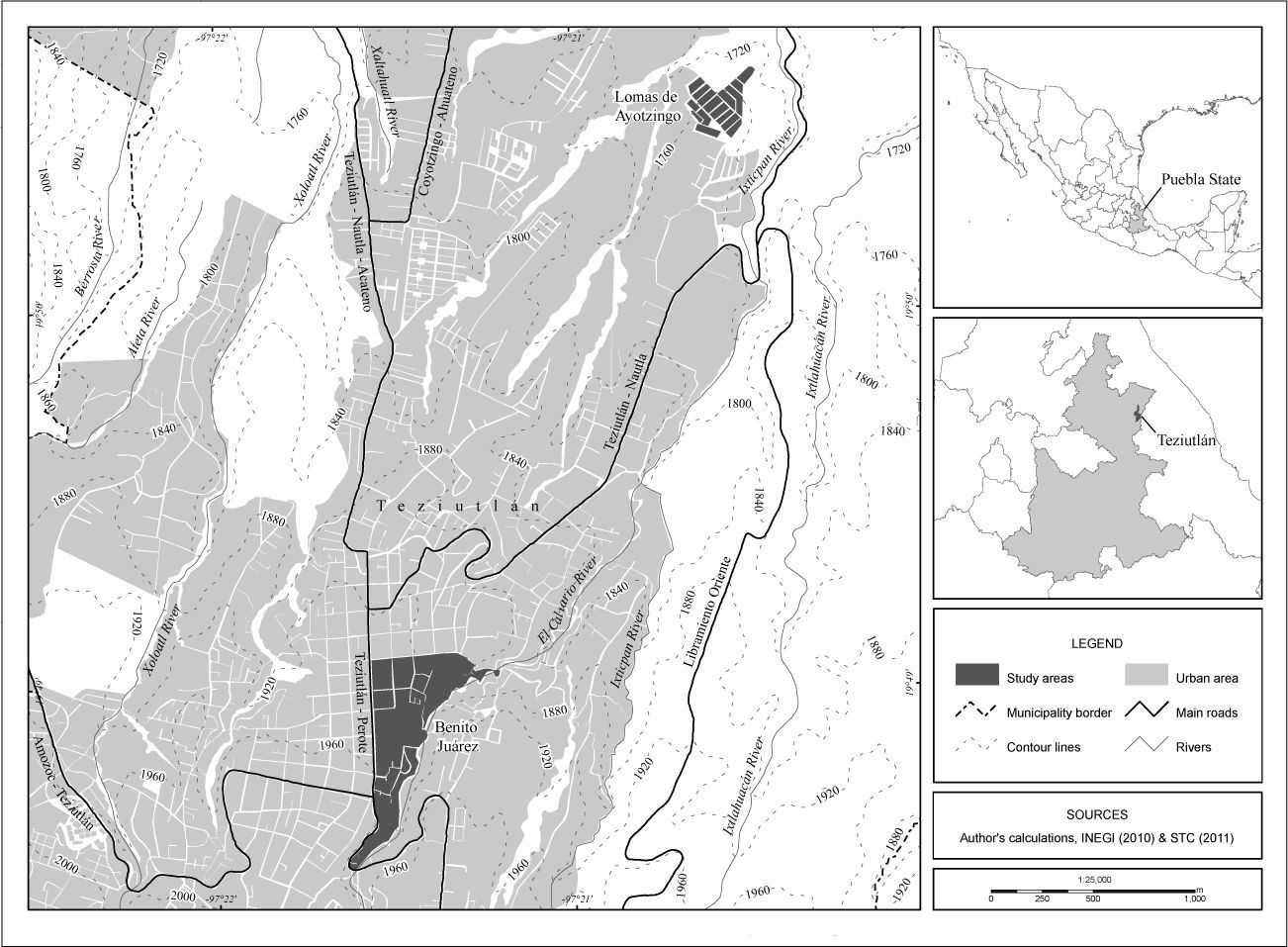

In order to achieve this objective, this research is based on a variation of Bourdieu's concept of habitus2 to understand the economic, symbolic and cultural dimensions that produce conditions of vulnerability based on a comparative case analysis of two neighborhoods (colonias) in Teziutlán; these neighborhoods share a geographical and cultural setting but differ on their landslide exposition and their experience with previous disasters. The selected case studies are Lomas de Ayotzingo, a resettled community, and Benito Juárez, an established neighborhood in a risk-prone area. In this research, the concept of risk habitus3 is used to understand judgments, decisions and actions of individuals with specific economic, social and symbolic resources in a specific field of action (risk prevention and reaction).

The questions guiding this research were: What are the forms of social and symbolic capital that constitute risk habitus in Teziutlan? To what extent do current forms of risk habitus increase or decrease the population's capacity to cope with landslide-related hazards? These questions guided a quantitative comparative research design, which was based on an extensive survey conducted in six communities of Teziutlan in April 2014. This survey focused on several dimensions of vulnerability to landslides, as well as risk perception. Also, a sub-sample of this survey was conducted for the two selected neighborhoods, containing more specific questions on social and symbolic capital. The survey results were processed through three statistical procedures: Chi Square test, Spearman correlations, and Principal Components Analysis.

We found that in general, members of both communities are certain about being affected in the future by a landslide event; this was associated with their previous individual disaster experience. The forms of social and symbolic capital that influence their conditions of vulnerability are different in each community, as we show in the statistical tests.

The article proceeds as follows. In the first section, the concept of risk habitus is explained in order to show its relevance for the analysis of underlying vulnerability conditions in these communities. This section also includes a brief discussion of the concept of social capital and how it might be particularly useful for a better understanding of people's judgments and actions around landslide risk. The second section presents the main characteristics of the selected case studies, including their social conditions and hazard context. The third section discusses the methods, statistical results, and their relevance. The paper ends with a review of the scope, contributions and limitations of the conceptual approach and the research design for the study of social vulnerability.

Risk habitus and social capital: key elements for understanding vulnerabilityThe concept of vulnerability is difficult to define, given the variety of approaches and academic fields that have used the concept, as well as its direct relationship with the complex and multidimensional concept of risk (Birkmann, 2006; Eakin and Bojorquez, 2008; Castro, 2010; Ruiz, 2012). In recent studies, vulnerability is understood as a differential condition associated with the coping capacity of people according to their class, gender, age and hazard exposition, a diversity of situations that stem from their physical, social, economic, and cultural characteristics (Eakin and Bojorquez, 2008; Castro, 2010; Ruiz, 2012). Among the approaches to explain risk, those linked to ‘new’ processes in modern societies have highlighted the complex nature of threats such as climate change, depletion of the ozone layer and the increasing inequalities of human societies (O’Malley, 2004; Beck, [1992] 2004). Nevertheless, in this paper, we follow a different path and address the persistence of some of the conditions influencing vulnerability, by using the concept of risk habitus, which is based on the social, economic, cultural, and symbolic capitals of these communities (Dumais, 2002:46) in the field of risk prevention and reaction. This concept helps explain the long-term collective practices leading to vulnerability (such as the long term Teziutlan's settlements growth in landslide-prone areas), and the day-to-day judgments and practices (Curtis et al, 1998:652) that reproduce such vulnerable conditions.

In the classic theory of habitus, the concept refers to a system of cognitive structures that guide a person's practical action, by naturalizing arbitrary viewpoints and procedures (Bourdieu, 1990:53). The basis of such dispositions is the volume and kinds of capital that each person embodies, and how these capitals are positioned in different fields, defined as areas of social action and decisionmaking. Risk reduction is analyzed here as a field in which both local authorities and communities have specific and sometimes contested viewpoints of what constitutes risk and what should be done to address it.

In this approach, capitals represent a combination of different resources that a person accumulates over time. These resources have a very important role in a person's options for action in a risk situation. Capitals can be economic, cultural, social and symbolic; the last three are based on impalpable and intangible resources, but since they are all convertible amongst each other, their availability has a big influence into the possibilities that each person has in his or her life (Bourdieu, 1986:247).

The different capitals may also have an enormous influence on the type of risk response. Capitals can be exchanged for other types of capital, which in turn can be used in different ways (Martinez, 1998:3). For example, economic capital can be transformed into symbolic capital when someone who has plenty of economic resources uses their free time to volunteer, or participate in political organizations, in which they strengthen their social capital. On the other hand, symbolic capital can be transformed into social capital, such as when someone with previous experience with a disaster situation shares that experience with his or her family networks and generates preventive actions.

Economic capital manifests through income and wealth, but also through goods and property rights, that is, a means of legitimate ownership (Bourdieu, 1986:135; Ra, 2011:18). On the other hand, cultural capital is mostly constituted by symbolic resources transferred by generation through class identity, in order to maintain or change the status or position within social structure. Cultural capital takes several different forms, such as incorporated (enduring arrangements), objectified (cultural goods) and institutionalized (academic degrees), (Bourdieu, 1986; Martinez, 1998:6). Finally, symbolic capital is the shape that capitals take when they are recognized and legitimated in a specific social context or field (Bourdieu, 1986:255; Bourdieu, 1997:108).

Though risk habitus may include a detailed analysis of all capitals, the original design of this research put more weight on social capital than other forms of capital, given the importance of social networks in vulnerability analysis (Moser, 1998; Alwang et al, 2001). In addition, measuring social capital necessarily takes into account the exchange of other forms of objectified or symbolic capital that supports the relationships a given person may have. As a result, it was useful to explore the implications and dynamics of social capital4 in more depth, in order to understand the role of social capital for risk habitus of Teziutlan residents.

Social capital is “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources, which are linked to possession of a durable network ofmore or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition —or in other words, to membership in the group”— (Bourdieu, 1986:248). According to this author, a person's social capital depends on their connections and the resources they can access through such networks. This key feature of social capital —as the means to mobilize other forms of capital and the overall resources to which each social group has access— is the one that we highlight in the statistical design of this work.

This perspective supports the definition of risk habitus as the actions, judgments and perceptions of individuals to face potential situations of risk under the influence of their different forms of capital, particularly their social capital. In this paper, we focus on the factors that reproduce vulnerability, by understanding the situated logic of action of people living in landslide-prone settlements in the case of Teziutlán.

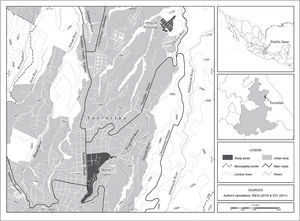

Case study contextPhysical characteristicsTeziutlán is located in the Northwest mountain chain of the province of Puebla; as much as 86% of the city's urban area is located on a steep slope. It has a humid tropical climate with year- round rainfall, but with a rain peak in summer. The average temperature range is 12-22° C and the average rainfall is 1 100-3 600mm a year. The land use in the municipality is divided among agriculture (25%), urban (27%), forest (30%), and grazing (17%). One of the factors in the 1999 landslide disaster was the extended erosion related to intensive urbanization and land use changes (Bitrán, 2000:182).

Social and economic characteristicsThe municipality of Teziutlán had 58 699 inhabitants in 2010 (27 126 men and 31 537 women), an average of 996 people per km2. More than half of the municipal population lives in small, scattered localities between 100 and 15 000 inhabitants (INAFED, 2015).

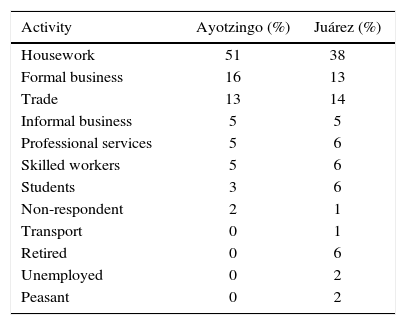

Within Teziutlan, the neighborhoods selected for this study were Lomas de Ayotzingo and Benito Juárez (Figure 1). Both Lomas de Ayotzingo and Benito Juárez are fully urbanized areas with all public services. Benito Juárez is an established neighborhood located in a risk-prone area. Most of its residents (48%) have lived in the neighborhood for at least 20 years. In contrast, Lomas de Ayotzingo is a resettled community created in 2000 to provide housing for victims of the October 1999 landslide disaster. In 2010, Benito Juárez had a population of 700. There are 98 households with an average of 3.4 persons per household. In contrast, Lomas de Ayotzingo had a population of 1 470 habitants in 2010, with 365 households and an average of four persons per household (INEGI, 2010). In the municipality of Teziutlán, the average educational level of people 15 years of age or older is 8.51 years: in Ayotzingo the average education level is 6.7 years, and in Benito Juárez it is 9.7 years.

According to the National Population Council (CONAPO, 2015), the municipality of Teziutlán has a low marginality index. In Ayotzingo, 54% of the population, and in Benito Juárez 40%, do not have health care. Only 0.62% of people do not have sewage services, 0.75% are without electricity services, and 2.02% are without drinking water services in the municipality of Teziutlán.

The area of study was selected because of Teziutlán's critical background regarding landslide hazards. The research design was part of a larger project, whose goal is the implementation of an early warning system for landslides in Teziutlán, combining both an analysis of risk perceptions and the physical measurement of unstable slopes with special equipment of monitoring and data logging management. The overall project covers six risk-prone neighborhoods in Teziutlán: Aire Libre, La Aurora, San Andrés, La Moraleda, Lomas de Ayotzingo, Centro, Benito Juárez and Xoloco. For the research discussed in this article, we selected the communities of Benito Juárez and Lomas de Ayotzingo, because of their contrasting hazard exposition and experiences with landslides disasters, even though they show similar characteristics regarding their social and cultural background.

MethodologyAfter the 1999 disaster, there have been several studies that have addressed landslide risk in Teziutlán. These studies have explored many issues related to the physical and geomorphological conditions of Teziutlán, including weather, rainfall patterns, soil type and urban growth (Alcántara y Flores, 2002; Cuanalo et al., 2006; CENAPRED, 2006 and 2008). Recent research has focused on the social dimensions of risk, such as social experiences, institutional capacity and factors influencing emergency responses. In this regard, an analysis of risk habitus and the communities’ social capital contributes to a better understanding of risk dynamics.

The methodological approach was framed as part of the research project named “Monitoreo, Instrumentación y Sistematización Temprana de Laderas Inestables (MISTLI) [Monitoring and early warning of unstable slopes in Teziutlán, Mexico]” funded by CONACYT (Project 156242) at the Institute of Geography (UNAM). The goal of this project is the implementations of an early warning system for landslides, using to analysis of risk perceptions and physical measurement of unstable slopes, with special equipment of monitoring and data logging management.

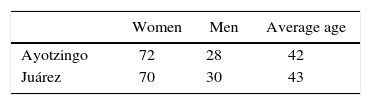

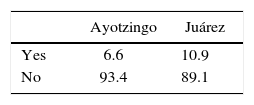

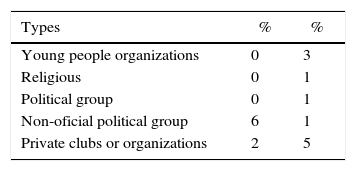

As mentioned, the information used to analyze capitals in these communities came from two surveys. The first, more comprehensive survey was applied in April 2014 by the MISTLI team to each household in six risk-prone neighborhoods in Teziutlán (listed above), (Landeros et al., 2015). We considered responses to 15 questions about social and symbolic capital, risk perception and socioeconomic profiles, only for the residents of Lomas de Ayotzingo and Benito Juárez. Given our interest in the components of risk habitus, particularly social capital that were not included in the first survey, in August 2014, we applied a second survey to a subsample of the first survey in Lomas de Ayotzingo and Benito Juárez using random sample (70% of households in each community). The total number of households in this sample was 140, 76 for Lomas de Ayotzingo and 64 for Benito Juárez, covering four additional themes: a) participation in any kind of groups or associations, b) family and place attachment, c) solidarity and reciprocity, and d) trust in local authorities.5 Responses were given by the head of household or members of legal age.

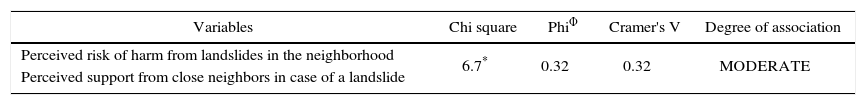

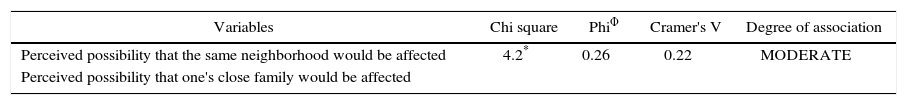

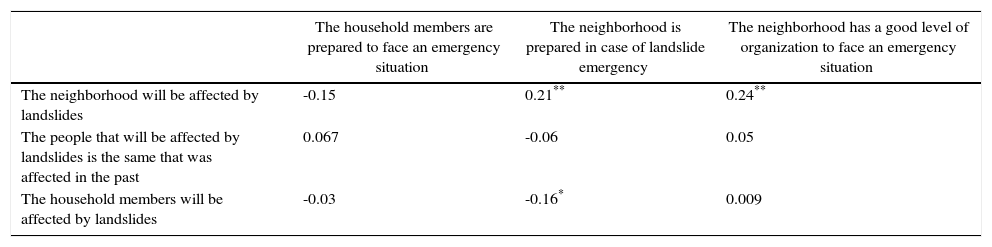

We processed these data with three types of statistical procedures: nominal association tests (Chi Square, Phi and Cramer's V) in the first Table 2 and 3, Spearman correlations (Tables 4-11), and Principal Components Analysis6 (Tables 12 and 13). Our variables were mostly nominal and categorical; although correspondence analysis has been widely used within habitus sociological studies, was not viable for this study given the type and heterogeneity of the categorical variables scales.

Degree of association between experience with landslides and perception of risk in Lomas de Ayotzingo.

| Variables | Chi square | PhiΦ | Cramer's V | Degree of association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived risk of harm from landslides in the neighborhood | 6.7* | 0.32 | 0.32 | MODERATE |

| Perceived support from close neighbors in case of a landslide |

** The p-value is a number between 0 and 1 representing the probability that this data would have arisen if the null hypothesis were true. A low p-value (such as 0.01) is taken as evidence that the null hypothesis can be ‘rejected’. Typically, values of either 0.01 or 0.05

Degree of association between actual experience with landslides and perceived possibility of a landslide event in Benito Juárez.

| Variables | Chi square | PhiΦ | Cramer's V | Degree of association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived possibility that the same neighborhood would be affected | 4.2* | 0.26 | 0.22 | MODERATE |

| Perceived possibility that one's close family would be affected |

Lomas de Ayotzingo: correlation matrix among hazard judgment and action, social capital, and risk preparedness.

| The household members are prepared to face an emergency situation | The neighborhood is prepared in case of landslide emergency | The neighborhood has a good level of organization to face an emergency situation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The neighborhood will be affected by landslides | -0.15 | 0.21** | 0.24** |

| The people that will be affected by landslides is the same that was affected in the past | 0.067 | -0.06 | 0.05 |

| The household members will be affected by landslides | -0.03 | -0.16* | 0.009 |

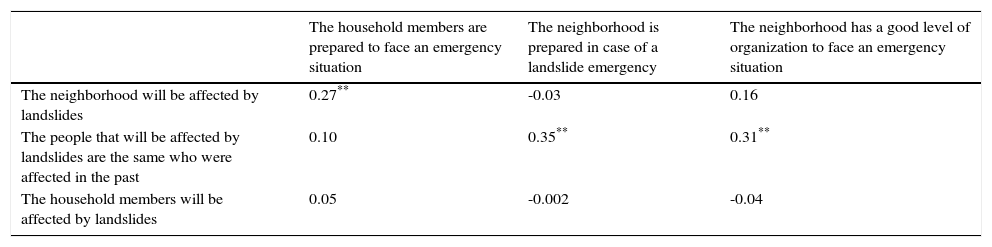

Benito Juárez: correlation matrix among hazard judgment and action, social capital, and risk preparedness.

| The household members are prepared to face an emergency situation | The neighborhood is prepared in case of a landslide emergency | The neighborhood has a good level of organization to face an emergency situation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The neighborhood will be affected by landslides | 0.27** | -0.03 | 0.16 |

| The people that will be affected by landslides are the same who were affected in the past | 0.10 | 0.35** | 0.31** |

| The household members will be affected by landslides | 0.05 | -0.002 | -0.04 |

*p< 0.10

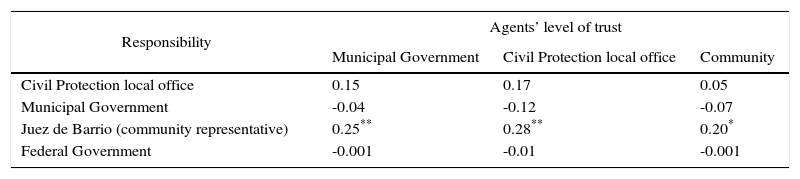

Lomas de Ayotzingo correlation matrix: participants ‘judgment of political actors’ responsibility to act in a landslide event, and the level of trust in their information and actions.

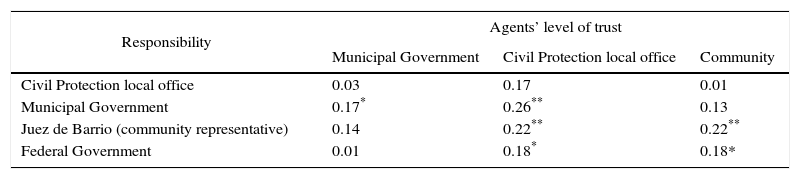

Benito Juárez correlation matrix: participants ‘judgment on political actors’ responsibility to act in a landslide event, and the level of trust on their information and actions.

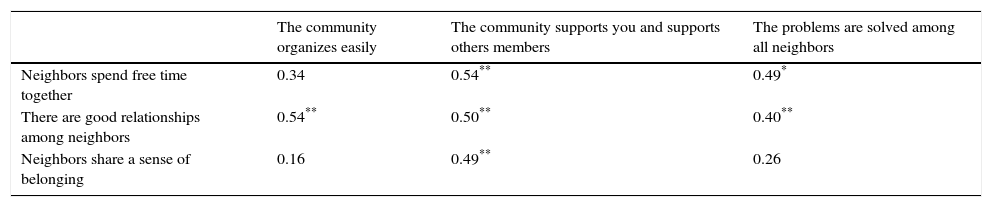

Lomas de Ayotzingo correlation matrix: solidarity, organization, and good relationship among neighbors.

| The community organizes easily | The community supports you and supports others members | The problems are solved among all neighbors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbors spend free time together | 0.34 | 0.54** | 0.49* |

| There are good relationships among neighbors | 0.54** | 0.50** | 0.40** |

| Neighbors share a sense of belonging | 0.16 | 0.49** | 0.26 |

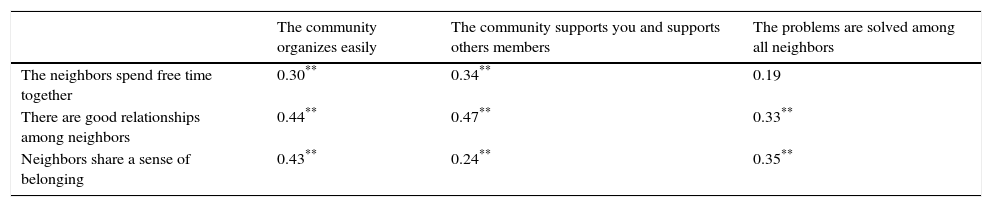

Benito Juárez correlation matrix of variables: solidarity, organization, and good relationships among neighbors.

| The community organizes easily | The community supports you and supports others members | The problems are solved among all neighbors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The neighbors spend free time together | 0.30** | 0.34** | 0.19 |

| There are good relationships among neighbors | 0.44** | 0.47** | 0.33** |

| Neighbors share a sense of belonging | 0.43** | 0.24** | 0.35** |

*p< 0.10

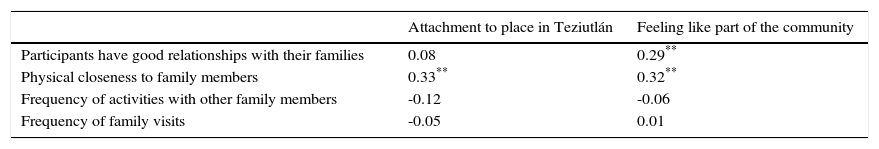

Lomas de Ayotzingo correlation matrix of variables: social capital and attachment to Teziutlán.

| Attachment to place in Teziutlán | Feeling like part of the community | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants have good relationships with their families | 0.08 | 0.29** |

| Physical closeness to family members | 0.33** | 0.32** |

| Frequency of activities with other family members | -0.12 | -0.06 |

| Frequency of family visits | -0.05 | 0.01 |

*p< 0.10

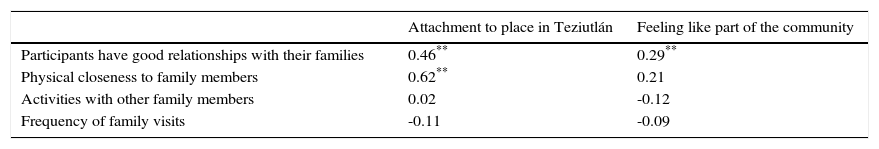

Benito Juárez correlation matrix of variables: social capital and attachment to Teziutlán.

| Attachment to place in Teziutlán | Feeling like part of the community | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants have good relationships with their families | 0.46** | 0.29** |

| Physical closeness to family members | 0.62** | 0.21 |

| Activities with other family members | 0.02 | -0.12 |

| Frequency of family visits | -0.11 | -0.09 |

*p< 0.10

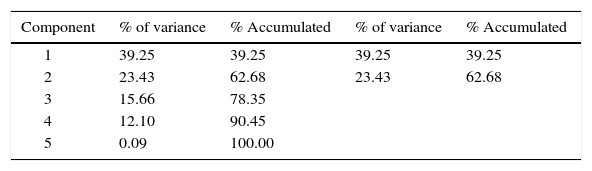

Selective social capital: principal components analysis.

| Component | % of variance | % Accumulated | % of variance | % Accumulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39.25 | 39.25 | 39.25 | 39.25 |

| 2 | 23.43 | 62.68 | 23.43 | 62.68 |

| 3 | 15.66 | 78.35 | ||

| 4 | 12.10 | 90.45 | ||

| 5 | 0.09 | 100.00 |

Selective social capital Correlation Matrix: principal components and original variables analysis.

| Variables | Cp1 | Cp2 |

|---|---|---|

| Participation in any group or neighborhood association | -0.01 | 0.14 |

| Easy organization of the community | -0.77 | -0.11 |

| Neighbors’ mutual help | 0.17 | 0.96 |

| Neighbors’ involvement in problem solving | -0.85 | 0.17 |

| Community's sense of belonging | -0.52 | 0.22 |

*Important correlations >.30.

The next section describes each of these statistical tests, the association between the variables of risk perception and action versus others that measured social capital by solidarity, family networks and support between neighbors. These tests allowed us to explore the relationships among the variables for risk perception and action, compared to other variables measuring solidary, family networks, and support among neighbors.

ResultsNominal association testsFor each community of analysis, the following tables show the degree of association among variables, comparing Chi Square, Phi and Cramer's V test results. In the case of Lomas de Ayotzingo, Table 2 shows a moderate association between residents’ judgment about their vulnerability to landslides and their perceived neighbors’ support in that situation.

In the case of Benito Juarez (the neighborhood close to the area with major damages in the 1999 landslide event), Table 3 shows residents had a moderate correlation with the perceived possibility that one's close family would be affected if a landslide event occurred. In the context of risk habitus, it suggests that most residents of Benito Juárez had symbolic capital from experience with landslide impacts. This experience could be explained by their perception that they would be affected by a landslide event.

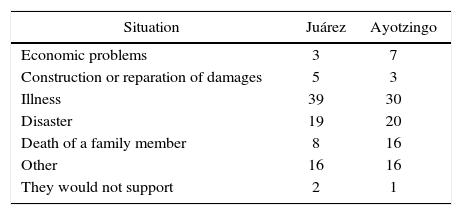

Social capital and risk habitusSocial capital relies on family ties, friendships and the size, level of reciprocity and type of social networks. The strength of other capitals strongly depends on the consolidation of social capital. This is the reason why social capital for understanding risk habitus was measured in this project by different proxies: level of solidarity, strength of family relations to face problematic situations, and how they work in situations of support. These variables are linked to other information regarding their hazard-related judgments and actions, and the level of preparedness to face the situations that might lead to a potential disaster.

The most significant correlations shown in Table 4 are between participants’ certainty that they will be affected by landslides, and their preparedness to face an emergency situation. Residents’ responses about suffering damages in a landslide correlate to two positive judgments: first, their neighborhood members are prepared to face risk situations; and second, their community is well organized for an emergency. There is a low negative correlation between their perceived preparedness and the certainty that members of a household will be affected by a landslide; if everyone is prepared to respond to an emergency, the evaluation of possible damages among members of a respondent's family will be low.

Table 5 shows that the most relevant correlation in Benito Juarez is between the certainty that communities that were affected in the past (such as this neighborhood itself) will be affected in the future for the same reason, and their good level of preparedness. This community's evaluation of their high possibility of being affected translates into an active preparedness of household members and the neighborhood. The actual level of preparedness was not measured in the survey, but people's judgments about it were included as part of their symbolic capital.

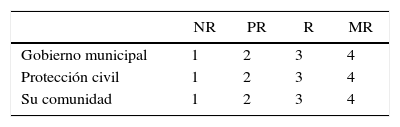

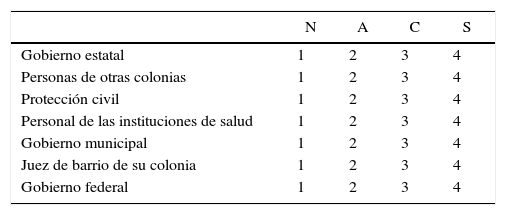

In addition to internal neighborhood networks, social capital is based on the level of trust and a positive relationship with local authorities. This relationship is crucial for access and integration of information, knowledge, as well as the physical and political resources in the field of risk reduction and risk habitus. These correlations show the level of trust in different representative actors who have specific responsibilities during a landslide event. These results show that during a landslide event, local agents and the community representatives help each other (see Tables 6 and 7).

Tables 5 and 6 show a high level of trust in local actors such as the civil protection local office, municipal government and community representatives. The interviewees say that they trust these authorities, based on previous experiences with landslide events and how the Civil Protection local office helped them. These political actors show a high level of social capital constructed from previous campaigns and their roles in landslide events.

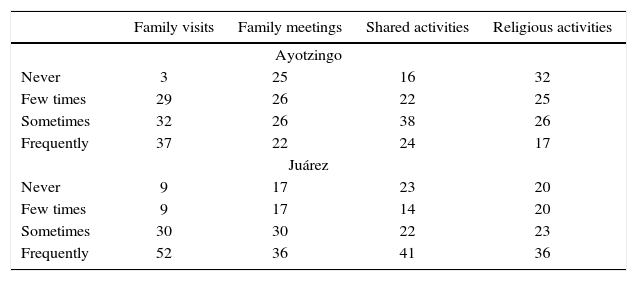

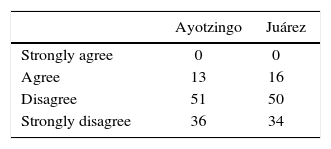

To measure residents’ level of solidarity, organization and good relationships with other members of their communities, we examined factors that influence a person's sense of belonging and the related capacity of organization within the neighborhood. The second survey (sub-sample) included specific items about the residents’ ability to organize and receive help by other members of their community (see Tables 8 and 9).

In Lomas de Ayotzingo, communication among neighbors was reported as high. Most participants expressed a high sense of belonging, which correlates with a good level of interaction in problem-solving situations. They particularly referred to the 1999 landslides as a landmark for the community's sense of cooperation in a disaster situation. In this regard, the results show a high level of social capital.

Table 9 shows the major correlation among variables is between community support and good relationships among neighbors. This is likely due to participants’ experiences of positive support during the landslide event in 1999. The participants have a sense of belonging because they have good relationships and communication. That suggests that the residents of Benito Juarez have built social capital through challenging situations, such as landslide events. This helps to explain why they acted as they did in the 1999 landslide.

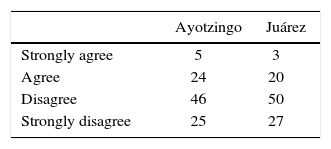

Finally, Tables 10 and 11 show participant's attachment to place in Teziutlan and their neighborhoods. We performed this test to see the strength of relationships among neighbors and family members. This test (Spearman correlations) used variables as a proxy of the combination of capitals. We considered variables such as good relationships among family members, and the physical closeness between friends and family members as proxies for social and symbolic capital. We found that participants in both communities show a high correlation between the physical closeness of the family home to the homes of friends, and feeling like part of their community. The results shown in Tables 10 and 11 demonstrate the importance of sense of belonging for the creation and support of social capital. The responses about mutual support in difficult economic situations, however, show that solidarity as an element of social capital is weak.

In Lomas de Ayotzingo, attachment to place correlated to family location, as well as to good relationships among family. Living close to family and/or friends created a feeling of security. Additionally, participants in this neighborhood expressed trust in local authorities (Table 6) and that the community organized easily (Table 8) which all contribute to social and symbolic capital. We believe this is because living close to family and/ or friends creates a sense of security.

In Benito Juárez, the most significant correlations were between the good relationships among family members, and the close proximity of the family home to the homes of their family and friends. Even when family members did not live close, they frequently visited family members in other communities.

The logic of vulnerability in these communities is based on elements of different capitals: trust in social networks and local authorities, judgments of good organizations and neighborhood groups (social capital), and the individual perceived capacity to face a landslide event (symbolic capital). In other words, symbolic and social capitals play an important role on how safe people feel in a risk situation.

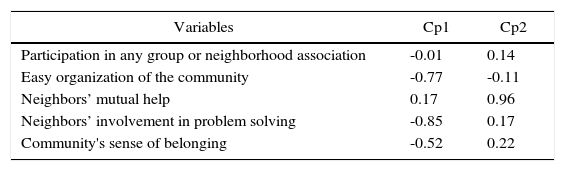

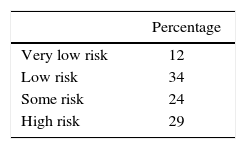

We will now describe social capital in both communities by using certain variables in a principal component test. The test included two types of analysis: general social capital and selective social capital. The first analysis is of general social capital, in which we assigned a value 1 to affirmative answers and 0 to negative answers. The second analysis is of selective social capital, which includes answers specifically associated with risk situations. We assigned a value of 1 to risk conditions, and a value of 0 to any other answer, including negative answers. Figure 2 shows the combination of variables according to principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2), (Figure 2).

Table 12 shows that the PC1 and PC2 explain 62.68% of variance; for this research this is enough to explain the importance of the variables selected in Figure 2. We tested many variables for selective social capital, then selected those variables most strongly correlated with original variables for Components principal analysis.

Table 13 shows a high correlation between PC2 and the original variables that identify the circumstances of neighbors’ support. The analysis shows that the most important factor to improve social capital is participants’ willingness to support other members of their communities in a risk situation. On the other hand, variables such as an easy organization of the community and neighbors’ involvement in problem solving are factors that reduced selective social capital.

The negative correlations can help us infer the factors that reduce selective social capital: in this case, the lack of easy organization of the community (CP2) and neighbors’ involvement in problem solving (CP1). In contrast, the positive correlation of neighbors’ mutual help increased selective social capital. We can infer the importance of mutual help in risk situations as a factor of selective social capital.

Both communities had a moderate association between the feeling of preparedness to face landslides, and the idea that communities would be able to act in an organized manner if a disaster situation occurs. Participants felt certain they would suffer damage if a landslide were to happen, however, they are confident the community would organize effectively to face such a situation.

Scope and limitationsOne of the objectives of this study was to identify which capitals are part of a risk habitus, which includes the economic, symbolic and cultural dimensions that produce conditions of vulnerability to landslides based on a comparative case analysis of two neighborhoods in Teziutlan, Puebla, Mexico. We hypothesized that Teziutlan residents’ risk perception would lower in relation to their closeness to their family and their sense of belonging, because they would feel safer living near family and friends. However, this was the case for the selected communities. Even though the people expressed a strong sense of belonging correlated to the physical closeness of family and friends, variables regarding their participation in organizations, groups, neighborhood associations, or their family relations do not correlate to any other variable that explains their levels of selective social capital.

We found that selective social capital —that is, the strength of reciprocity and solidarity in risk situations— in both communities is moderate: there is little communication and social cohesion among residents in relation to problems of landslide vulnerability. In general, however, participants thought that in a risk situation, their community would organize to face it.

On the other hand, symbolic capital is high. Participants highly trust local civil protection officers and other local authorities such as their ‘juez de barrio’ (community representative); they believe these authorities will help them in a landslide situation. Additionally, participants’ sense of security also related to their sense preparedness to respond to a disaster situation, even though they have not performed concrete actions related to disaster preparedness.

The article is an example of how to apply the concept of social capital and risk habitus to the study of disaster risk in a community, using surveys and statistical analysis. This approach would be strengthened by ethnographic and historical analysis that would take into account personal experiences with past landslide events, as well as during and after a landslide event. This could provide evidence about whether people would organize to deal with risk, and the factors influencing how to prepare and respond to a disaster at an individual and community level.

In this research, we focused on social and symbolic capital. We did not explore economic and cultural capital, however, the methodology applied here can be used to analyze other forms of capital that integrate Bourdieu's proposal. For example, in future research we could test the relation of formal and informal education on responses to disaster situations, as well as other factors such as the role of media and gender differences, which are all part of cultural capital.

ConclusionsIn this article we analyzed how conditions of disaster vulnerability are produced. Using the case of two communities in Teziutlan, Puebla, Mexico, we used statistical analysis of survey results to explore how social and symbolic capital are related to risk perception. One of the differences between the two communities of study was their historical experiences with and exposure to landslide events. Lomas de Ayotzingo was created in 2000 as a resettled community for those affected by a major 1999 landslide event. Benito Juárez was established several decades ago in a landslide-prone area, is home to many original residents

The findings in both communities show that participants’ perception of risk is not influenced by whether they live in a hazardous area or not. Rather, their perception of risk is related to their perceptions of preparedness to face a risk situation and their historical experience. The results suggest one reason for this belief is their high level of trust that local authorities —such as the community representative and local civil protection office— will help them in a disaster situation. Additionally, participants thought that their communities could organized easily in a disaster situation because residents tend to have a good relationships. In other words, social capital is high.

The participants’ judgment about risk is associated with the possibility that they will suffer some damage, reflecting their individual experience. In a symbolic context, their actions can be interpreted as a historical construction based on the shared landslide disaster experience of 1999, from which they created shared beliefs and judgments. This may explain why, for example, participants from Lomas de Ayotzingo expressed a strong judgment of being at high risk of a landslide event, despite that them no longer live in a landslide-prone area.

Although both communities have some social organizations, groups and neighborhood associations, there are few people who belong to any of these. Most of these associations exist just for recreational purposes. So, social capital exists as reciprocity, not as ‘hard capital’ organizations in which communities could discuss and take action about their problems.

In sum, members of both communities are certain about being affected in the future by a landslide event; this was associated with their previous individual disaster experience. The forms of social and symbolic capital that influence their conditions of vulnerability are different in each community, however, as the results of the statistical tests demonstrate. In particular, we emphasize the certainty of Benito Juárez residents that in future disaster events, they would suffer damages similar to previous disaster events. In both Benito Juárez and Ayotzingo participants believed in their capacity to respond to a landslide even when they had not prepared for such an event.

Finally, we propose the conceptual instrument of risk habitus as an approach to understanding the underlying conditions of vulnerability in a specific context, rather than a proper vulnerability measurement. This study contributes to a deeper understanding of the production of vulnerability by analyzing people's knowledge of local landslide hazards, shared disaster experiences, judgments about potential and future damages, family support and close relationships, solidarity between neighbors, and trust in local authorities. These elements are all part of the specific conditions of vulnerability to landslides, and should be considered in future research for a better understanding of risk response and implementation of early warning systems.

This work was supported by CONACYT 156242, Project MISTLI: Monitoreo, Instrumentación y Sistematización Temprana de Laderas Inestables.

2. ¿Pertenece usted a alguna organización comunal (grupo, club, organización de vecinos)?

Otro____________________

____________________________

A cuál, ¿cómo se llama?____________________________

____________________________

2.1 ¿Podría contarme brevemente sobre la historia de su organización? (¿En qué año se fundó, desde cuándo pertenece usted a esta organización, y/o cuál fue el propósito por el cual se creó la organización?)

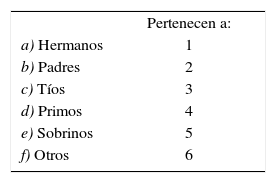

3. ¿Hay otros miembros de su familia que pertenecen a grupos u organizaciones comunales?

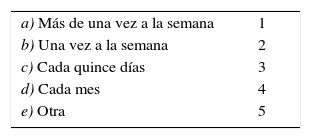

4. Por lo general, ¿cuántas veces a la semana se reúnen?

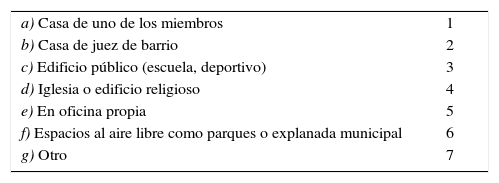

5. ¿En qué lugar acostumbran tener sus reuniones?

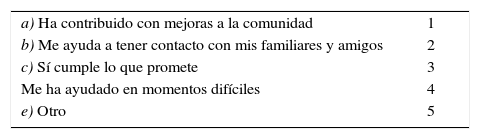

6. ¿Qué le gusta o qué obtiene por participar en ese grupo u organización?

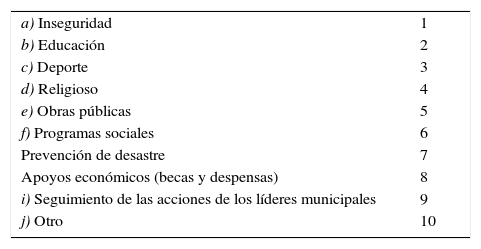

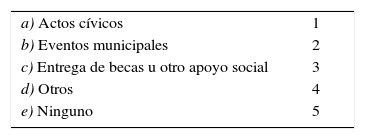

7. De los siguientes temas, mencione principal de el motivo sus reuniones:

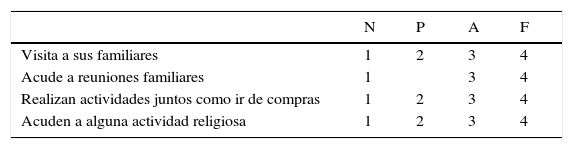

8. Además de asistir a las reuniones con los miem-bros de su grupo u organización, mencione por favor si acude a actividades como:

De las siguientes situaciones, ¿con cuánta frecuencia realiza las siguientes acciones? Dígame si lo hace Frecuentemente (F), A veces (A), Pocas veces (P) o Nunca (N).

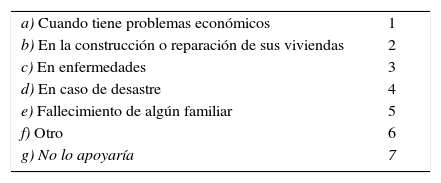

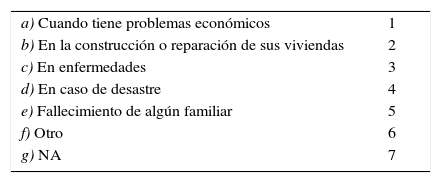

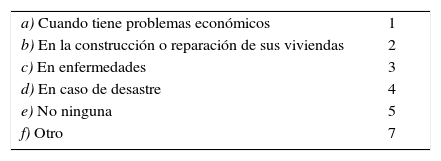

13. Bajo qué circunstancias usted apoyaría a un miembro de su comunidad:

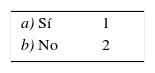

14. Usted, ¿alguna vez ha necesitado del apoyo de sus vecinos?:

14.1 Si sí, ¿bajo qué circunstancias?:

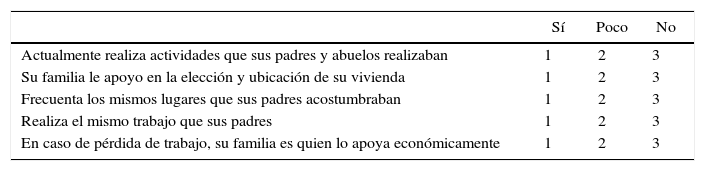

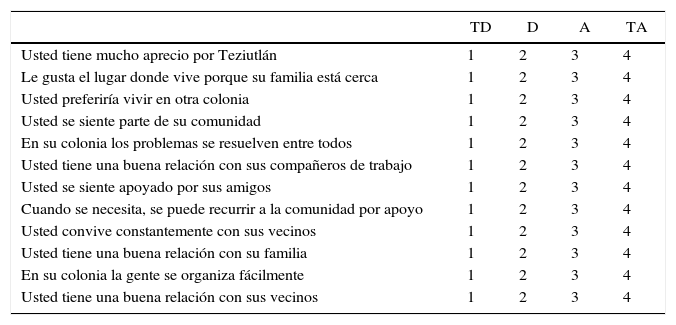

De las siguientes afirmaciones, indique que tan de acuerdo o en desacuerdo está.

| Sí | Poco | No | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actualmente realiza actividades que sus padres y abuelos realizaban | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Su familia le apoyo en la elección y ubicación de su vivienda | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Frecuenta los mismos lugares que sus padres acostumbraban | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Realiza el mismo trabajo que sus padres | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| En caso de pérdida de trabajo, su familia es quien lo apoya económicamente | 1 | 2 | 3 |

20. ¿Usted sabe cómo se eligen a los jueces de barrio?

21. ¿Ha participado en la elección de algún juez de barrio?

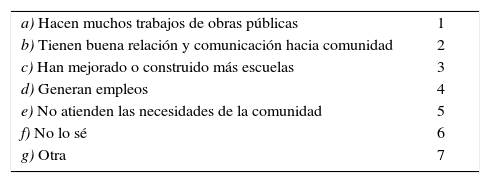

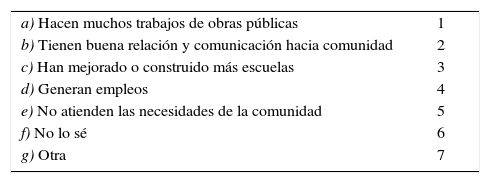

22. ¿Cómo describiría lo que hacen las autoridades (juez de barrio) con respecto a su comunidad?

23. ¿Cómo describiría lo que hacen las autoridades (gobierno municipal) con respecto a su comunidad?

24. ¿Qué líder recuerda usted por las obras que hizo en su comunidad? (Se codiicó una lista de nombres.)

25. ¿Cuál fue la obra que hizo, por lo cual usted lo recuerda? (Se codiicó una lista de obras.)

26. ¿Cuáles fueron algunos de los beneicios que le ofrece el partido que más le simpatiza? (Se codiicó una lista de beneicios.)

27. ¿Hay algún líder que lo haya apoyado en una de las siguientes situaciones?

Edad: _________________________________

Ocupación: ____________________________

Dirección:______________________________

Notas y comentarios

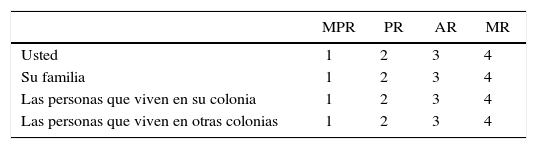

Indique el grado de riesgo que tienen las siguientes personas de sufrir algún daño por deslaves o derrumbes. Le recuerdo que las opciones son Muy poco riesgo (MPR), Poco riesgo (PR), Algún riesgo (AR) y Mucho riesgo (MR).

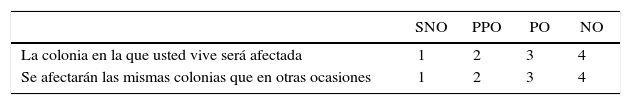

Utilizando las siguientes respuestas, si sucediera un deslave o derrumbe, indique qué tan posible es que sucedan las siguientes situaciones. Estoy seguro que no ocurrirá (SNO), Existe poca posibilidad de que ocurra (PPO), Es posible que ocurra (PO), y Estoy seguro que ocurrirá (SO).

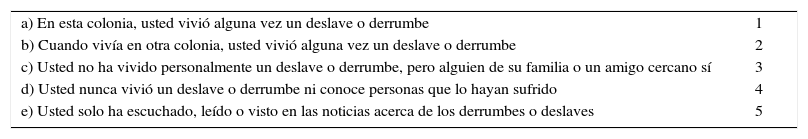

De las siguientes oraciones dígame cuál es la que mejor indica su experiencia con derrumbes o deslaves.

| a) En esta colonia, usted vivió alguna vez un deslave o derrumbe | 1 |

| b) Cuando vivía en otra colonia, usted vivió alguna vez un deslave o derrumbe | 2 |

| c) Usted no ha vivido personalmente un deslave o derrumbe, pero alguien de su familia o un amigo cercano sí | 3 |

| d) Usted nunca vivió un deslave o derrumbe ni conoce personas que lo hayan sufrido | 4 |

| e) Usted solo ha escuchado, leído o visto en las noticias acerca de los derrumbes o deslaves | 5 |

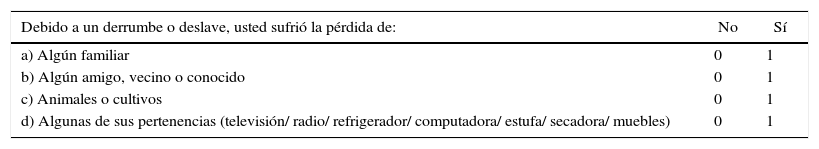

¿Alguna vez tuvo que salir de su casa (evacuar) por riesgo de un deslave o derrumbe? Si es así, ¿cuándo? (año-número, mes-número).

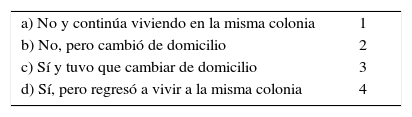

¿Usted perdió su casa debido a ese deslave o derrumbe? o ¿Usted conoce alguien que haya perdido su casa debido a un derrumbe? (sólo una opción).

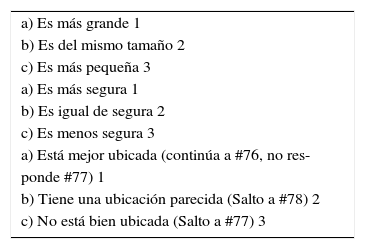

En comparación con la que perdió o dejó, la casa en la que vive actualmente: (solo una opción).

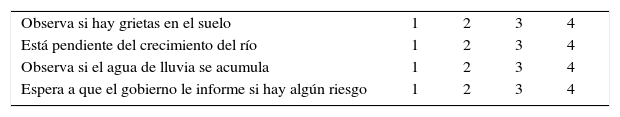

Para saber si puede ocurrir un derrumbe o un deslave ¿Con cuánta frecuencia realiza las siguientes acciones? Dígame si lo hace Nunca (N), Pocas veces (P), A veces (A), o Frecuentemente (F).

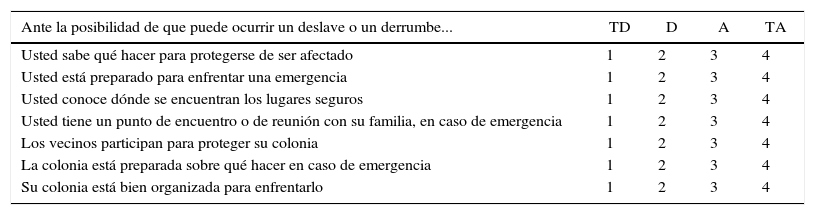

Ahora le voy a leer una serie de afirmaciones, le pido que por favor me indique qué tan de acuerdo o en desacuerdo está con cada una, utilizando las siguientes respuestas: Totalmente en desacuerdo (TD), En desacuerdo (D), De acuerdo (A), y Totalmente de acuerdo (TA).

| Ante la posibilidad de que puede ocurrir un deslave o un derrumbe... | TD | D | A | TA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usted sabe qué hacer para protegerse de ser afectado | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted está preparado para enfrentar una emergencia | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted conoce dónde se encuentran los lugares seguros | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted tiene un punto de encuentro o de reunión con su familia, en caso de emergencia | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Los vecinos participan para proteger su colonia | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| La colonia está preparada sobre qué hacer en caso de emergencia | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Su colonia está bien organizada para enfrentarlo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

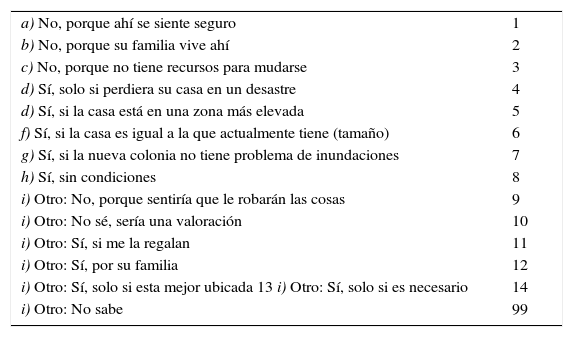

Si le dijeran que es necesario que se cambie de casa porque en la zona en la que vive hay riesgo de deslaves y derrumbes, ¿usted aceptaría?

| a) No, porque ahí se siente seguro | 1 |

| b) No, porque su familia vive ahí | 2 |

| c) No, porque no tiene recursos para mudarse | 3 |

| d) Sí, solo si perdiera su casa en un desastre | 4 |

| d) Sí, si la casa está en una zona más elevada | 5 |

| f) Sí, si la casa es igual a la que actualmente tiene (tamaño) | 6 |

| g) Sí, si la nueva colonia no tiene problema de inundaciones | 7 |

| h) Sí, sin condiciones | 8 |

| i) Otro: No, porque sentiría que le robarán las cosas | 9 |

| i) Otro: No sé, sería una valoración | 10 |

| i) Otro: Sí, si me la regalan | 11 |

| i) Otro: Sí, por su familia | 12 |

| i) Otro: Sí, solo si esta mejor ubicada 13 i) Otro: Sí, solo si es necesario | 14 |

| i) Otro: No sabe | 99 |

¿En qué grado considera que es responsabilidad de... actuar cuando existe el riesgo de que haya un derrumbe o deslave, o cuando éste ya sucedió? Nada responsables (NR), Poco responsables (PR), Responsables (R), y Muy responsables (MR).

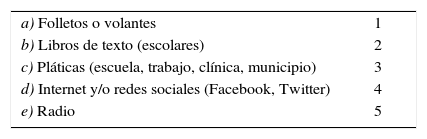

¿En dónde ha leído, visto o escuchado información sobre cómo prevenir o responder ante un derrumbe o deslave ? (puede marcar más de una opción).

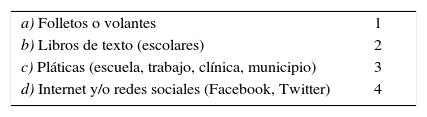

¿Por qué medio preferiría recibir información sobre cómo prevenir o responder ante un derrumbe o deslave? Dígame cuál preferiría en primer lugar, cuál en segundo lugar y cuál en tercer lugar.

Para recibir información sobre cómo prevenir o responder ante un derrumbe o deslave, ¿qué tanto confiaría en los siguientes personajes? Usted no confiaría: Nunca (N), confiaría A veces (A), confiaría Constantemente (C), confiaría Siempre (S).

De las siguientes afirmaciones, indique qué tan de acuerdo o en desacuerdo está con cada una de ellas. Las opciones son: Totalmente de acuerdo (TA), De acuerdo (A), En desacuerdo (D) y Totalmente en desacuerdo (TD).

| TD | D | A | TA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usted tiene mucho aprecio por Teziutlán | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Le gusta el lugar donde vive porque su familia está cerca | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted preferiría vivir en otra colonia | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted se siente parte de su comunidad | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| En su colonia los problemas se resuelven entre todos | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted tiene una buena relación con sus compañeros de trabajo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted se siente apoyado por sus amigos | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Cuando se necesita, se puede recurrir a la comunidad por apoyo | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted convive constantemente con sus vecinos | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted tiene una buena relación con su familia | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| En su colonia la gente se organiza fácilmente | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Usted tiene una buena relación con sus vecinos | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

1. Percentage of sampled population that participates in any organization.

2. Percentage of active members of local organizations.

3. Percentage of sampled population that has good relationships with their families.

4. Percentage of sampled population that declared willingness to support a member of the community.

5. Percentage of sampled population that expresses a strong sense of belonging.

6. Percentage of sampled population that beliefs that their community organizes easily.

7. Percentage of perceived exposure to landslides of sampled population.

8. Economic profile of sampled population.

In October 1999 a five-day heavy rainfall, originating from Tropical Storm number 11, triggered floods, mudslides and landslides in Teziutlan. As a result, one hundred people died, 500 houses were destroyed, and 1 200 houses were partially damaged (cenapred, 2008; Alcántara and Flores, 2002).

Habitus is defined as a “system of durable, transposable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures, that is, as principles which generate and organize practices and representations that can be objectively adapted to their outcomes without presupposing a conscious aiming at ends or an express mastery of the operations necessary in order to attain them, which influences the actions that one takes” (Bourdieu, 1990:53; Lizardo, 2004:378). That is, the habitus is a set of ways of acting, thinking and feeling associated with certain conditions of life (Martínez, 1998:7).

Although the concept risk habitus has not been applied elsewhere in the analysis of vulnerability to natural hazards, there are several works in which this perspective has proved its usefulness in understanding other forms of vulnerability (Sakdapolrak, 2007; Wiesner et al., 2006; Geldstein et al., 2011).

The concept of social capital emerged in the last two decades of the 20th Century, when sociologists, such as Coleman (1988, 1990) and Putnam (1993) explored the concept in depth (Lin, 2001:21). Their analysis stemmed from different social backgrounds and in diverse scales. For example, Putnam defined the concept mostly from the organizational perspective, while Coleman defined social capital as any resources (expectations, information, and social norms) that facilitate individual or collective action (Coleman, 1988:95). In general, Coleman applied social capital in two dimensions: a) how some groups maintain social capital as a collective good and b) how a collective asset has influence over increasing life chances of the members of group. The central point of this perspective is to explore the process and the elements of the production of a collective good.

Details of the survey are included at the end of this paper. For full databases please contact the authors.

Principal component analysis is a statistical test that synthesizes information, and reduces the dimensions (number of variables) by optimizing the information they contain as much as possible, with the objective of better explaining the correlation between original variables.