This paper identifies the Spaniards’ involvement in the opium trade in China at the beginning of the 19th century. Several sources have been consulted, mainly the Jardine Matheson Archive at the University of Cambridge and the Archivo General de Indias in Seville. These activities took place from the end of the Manila Galleon until 1830, and were undertaken by some employees of the Spanish Royal Philippine Company in Calcutta and Canton in their private businesses. These houses collaborated closely with the British firms during the opium boom, and Manila private financial support was provided. Thus, Spaniards undoubtedly made a fundamental contribution during a key stage of development of the opium economy and evolution of modern Chinese history, being a precedent of what became the prestigious British company Jardine, Matheson & Co.

Este trabajo identifica la participación de españoles en el comercio del opio en la China de principios del siglo XIX. Se sirve de fuentes diversas, especialmente del Jardine Matheson Archive de la Universidad de Cambridge y del Archivo General de Indias de Sevilla. Dichas actividades tuvieron lugar desde el final del Galeón de Manila hasta 1830, y fueron llevadas a cabo por empleados de la Real Compañía de Filipinas en Calcuta y Cantón en sus negocios privados. Se efectuaron en intensa colaboración con las firmas británicas, en pleno estallido del sector del opio, y con el apoyo financiero de iniciativas privadas manileñas. Los españoles hicieron así una aportación indiscutible en un momento clave del desarrollo de la economía del opio, fundamental en la evolución de la China contemporánea, siendo además un antecedente de la destacada firma británica de Jardine, Matheson & Co.

The opium trade, carried out mostly by British merchants in Calcutta (Kolkata) and Canton (Guangzhou) from the end of the 18th century until the middle of the 19th, is one of the central themes of contemporary Chinese historiography. Revisions of the role of opium in Chinese society have developed in recent years, detaching it from negative perceptions and anxieties which have been constructed subsequently, without contemporary judgements about psychoactive substance consumption and playing down its harmfulness (Newman, 1995; Howard, 1998; McMahon, 2002; Dikötter et al., 2004; Zheng, 2005; Paulès, 2011). Opium consumption in other Asian societies has been analysed as well, together with the substance relevance in European imperial finances; opium has also been dissociated from monetary appreciation in China during the Jiaqing (1796–1820) and Daoguang (1820–50) eras (Polachek, 1992; Trocki, 1999; Brook & Wakabayashi, 2000; Bello, 2005; Lin, 2007).

Revisions of the opium trade in East Asia (Derks, 2012) and of the Canton trade in particular have also been made (Hao, 1986; Cheong, 1997; Van Dyke, 2005). However, it is necessary to reassess the still prevalent model centred on the British monopoly of the field, on the routes linking India with Southern China, by which certainly the whole of this trade was carried on. Still, no evaluation of all nuances of the Canton trade or of the involvement of other nationalities has been made, and there has been an excessive stress on the events leading to the first Opium War (Greenberg, 1951; Dermigny, 1964; Cheong, 1979; Le Pichon, 1998). Some exceptions to this are the studies about US participation in Cantonese trade (Downs, 1968, 1997), Parsi involvement in the opium trade (Palsetia, 2008) and some approaches to the Portuguese role (Guimarães, 1996).

This article1 deals with a Spanish involvement in the opium trade, with its specific features, undertaken by the employees of the Royal Philippine Company (Real Compañía de Filipinas, from now on, RCF) in their private businesses, in close collaboration with the British private merchants, roughly from 1815 until 1830, which also relied on Philippine capital. In addition, in the Spanish colony the profits from opium were also considered from the 1820s onwards, and an official system of farming out (‘estanco de anfión’) was established from 1844 aimed at Chinese consumers, though we will not go over it here (Wickberg, 1965, pp. 49–50, 113–119; Gamella and Martín, 1992; Bamero, 2006). Despite its transitional character, Spanish involvement in the opium sector was of great relevance, not only for its numbers but also for the precedents established, which also illustrate a Spanish link with Chinese foreign trade, still too little known to the historians. Only Cheong (1979) has analysed this subject, establishing a necessary basis for a knowledge of this area, yet there was a need of a more comprehensive contextualization, avoiding an approach by which this involvement appears only as a kind of appendage of a mainly British sector, ignoring the Pacific links of the Chinese foreign trade. This limitation has been partly counteracted by the Spanish historian Fradera (1999).

2Shortcomings in historiographyThis overlooking of Spanish involvement can be explained by the absence, already pointed out, of a revision of the whole of the Cantonese trade. The discourse about the Canton commercial trade focuses mainly on English language sources, and seldom strays away from the India–China routes, disregarding the Pacific Ocean as well as Southeast Asia. This ignores the polyphony that defined this commerce, which included the Manila Galleon route, the proximity of the Philippine islands, the circulation of silver, the action of the RCF and, thereafter, the development of the Philippine export economy. In addition, this Pacific aspect has been analysed by a different historiographic tradition from the former, which is still too unfamiliar with Asian realities, and apart from some exceptions, the Galleon discourses very rarely deal with its connection to the Chinese economy (Cheong, 1965a; Alonso Álvarez, 2004; Martínez Shaw, 2007; Martínez Shaw and Alfonso Mola, 2007). Additionally, a comprehensive revision of the RCF, and its place in the Asian trade, is still lacking even in the most cited work on the subject, that of Díaz-Trechuelo (1965).

Another element explaining the absence of an approach to this subject has been the difficulty of defining some activities in circumstances in constant transition. This process was triggered by the Napoleonic wars, the end both of the Manila Galleon and of the RCF, the independence of the Spanish American republics, along with the expulsion of the Spaniards from Mexico in 1827, and also by the constant changes in Western commerce in Asia both in China and in the Philippines and in the opium sector during the first decades of the 19th century. The Spanish involvement is explained because of these constantly changing circumstances, and for this Cheong (1979, pp. 55–85) refers to a ‘Spanish connection’, between two stages of Western trade in China, from chartered companies to free trade. It can also be applied to the link between the Indian and the Pacific spheres, between Britons and Spaniards involved in the opium trade.

Furthermore, the dispersion and diversity of sources is another reason for this oversight. For this study, several archives have been used, related to two thematic areas, one to the RCF and the Spanish empire, and the other linked to private initiatives. As regards the first, the Archivo General de Indias in Seville has been the main source; however, its bias is too ‘metropolitan’ as it only reflects the concerns of Bourbon elites and the Board of Administration (Junta de gobierno) of the RCF. In order to counteract this tendency, the diaries of Manuel de Agote, first factor of the RCF in China at the end of the 18th century, kept in the Untzi Museoa-Museo Naval in San Sebastian, have been resorted to. These are the only known source for the Company at a factory level (Permanyer-Ugartemendia, 2012). Other sources about the Spanish official attitudes in the Philippines have been used, such as the Archivo Histórico Nacional and the Archivo del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, both in Madrid, besides the Archivo de la Real Academia de la Historia de Madrid and the National Archive of the Philippines.2

With respect to the private initiatives, the Jardine Matheson Archive in the Cambridge University Library has been the main source, rarely used by Spanish historians to this day. It holds all documents related to Jardine, Matheson & Co., the main private company in the opium trade in China, an indispensable source for research in the history of opium trade in Asia. Various Spanish firms and individuals were part of this company's branches and earlier formations, mainly, Yrisarri y Ca, formed by the Scottish James Matheson, before being a partner of Jardine, Matheson & Co., and the Basque-Navarrese, Cartagena-born, Francisco Xavier de Yrisarri. The correspondence of Yrisarri y Ca is the most homogeneous register of private Spanish activities not only of this firm but of its counterparts as well.3 Other sources have been employed, namely the Archives Nationales de France and the Archives de Paris, in order to establish Lorenzo Calvo's initiatives, another of the main actors in this paper.4

3A transitional prominenceAt the end of the 1810s and during the succeeding decade, the RCF employees in Calcutta and Canton reoriented their private businesses into the intra-Asian trade between the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea and more specifically, in the opium sector. This concurred with two fundamental factors: the end of the Manila Galleon in 1815 on one hand, and the opium boom in the first half of the 1820s on the other. In Canton, together with the main British firms of Charles Magniac & Co. and W. S. Davidson & Co. – precursors of Jardine, Matheson & Co. and of Dent & Co., respectively – houses like the Spanish Lorenzo Calvo y Ca and the Hispano-British of Yrisarri y Ca, both made up of RCF employees, will have a prominent role in this rise (Cheong, 1979, pp. 97, 101).5 In Calcutta, a Spanish house also formed by RCF workers operated beside the British firms, Manuel Larruleta y Ca, which in 1823 became Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca. Together with the British, the Spaniards would participate actively in this growth in the opium trade, would develop new procedures and would be victims of speculative practices as well.

As has already been said, we should place this Spanish participation in the continuous transition processes in all the determining factors affecting China external trade and more specifically, the opium trade. Two main parameters determined Western trade in East Asia in the first decades of the 19th century, namely, the increase of the private activities after the Napoleonic Wars and the growing lack of liquidity when the end of the Manila Galleon was approaching in 1815. The Charter Act of 1813 put an end to the East India Company (from now on, EIC) monopoly in British Indian trade, by which the presence of country traders and their silver demand increased. The definite opening of Manila to international trade in 1814, which was gradually implemented from 1789 (Martínez Shaw, 2007, pp. 52–70), and the Chinese prohibition edicts on silver exports from 1809 (Morse, 1926, vol. III, pp. 127–129), were closely related to all these variables, to which the opening of Singapore in 1819 should be added. Not too long after, the end of the Spanish American empire affected all silver distribution patterns – not so much due to the end of the supply but due to the breakdown of the Spanish peso standard (Irigoin, 2009) – and more particularly related to the object of our study here, it deepened the RCF's crisis, which had already set in. The factory in Canton was closed in 1821, and activities in Calcutta persisted at least until the suspension of its factors’ private activites at the beginning of 1827.

Chartered companies used to sanction a margin for the private activities of their employees, and the RCF was no exception, as its employees’ activities burgeoned during the Company's final years: the factors of Calcutta and Canton, in collaboration with the British, focused on these private businesses and more specifically, on the main thriving sector at that moment – opium. In Canton, Calvo y Ca and Yrisarri y Ca received opium consignments from Calcutta from the Spanish house of Larruleta y Ca/Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca as well as from its British counterparts, and more specifically, from Mackintosh & Co. These consignments were acquired in Calcutta, in auctions where opium produced in the EIC plantations in Patna (Bihar) and Ghazipur (Uttar Pradesh) was sold, besides that of Malwa and Daman (Damão), from the Western regions (Trocki, 1999, pp. 61–73). The consignees in China were familiar with the tangled stipulations of the Chinese trade (the so-called ‘Canton system’) (Van Dyke, 2005), and took charge of disposing of the opium in the Pearl River (Zhujiang) estuary, and also of sending back its proceeds, after retaining commission profits.

Two problems affected China houses, limitations to metal movement from Canton – for the aforementioned edicts against silver exports – and the absence of profitable return goods to India. This compelled the use of bills, both private and of the EIC on Bengal, which were acquired in the Company's treasury in Canton, and also compelled the diversification of return goods, such as sugar, saltpetre, cassia bark, metals and sulphur, besides raw silk and nankeens – pieces of high quality China cotton cloth – which had been a monopoly of the EIC respectively until 1822 and 1824 (Cheong, 1973, p. 65). Tea was an unusual product as the British Company still retained its monopoly on it. Besides, Spanish houses in China also resorted to Philippine trade and banking activities, as analysed later.

Spaniards and British collaborated in this stage of the Western trade in China, the former offering benefits in an uncertain setting of constant changes. This was true from the end of the 18th century, due to their access to silver and to the Philippines. In a context of continuous lack of liquidity diversification was the main strategy to follow, and the RCF represented an alternative supply.6 In addition, the Spanish Company made possible an entrance into the Philippine market – the territory under European sovereignty closest to China, whose potential as a field of expanding activities was perceived long before the Bourbon reforms of the 18th century, and its commercial links with British India were the second in importance after the Sino-Indian trade. During the Napoleonic Wars, trade with the subjects of a power hostile to the British government was forbidden, which benefitted the Calcutta factory of the RCF (Cheong, 1965b, 1970, 1971; Furber, 1935; Quiason, 1966; Chaunu, 1960).7

The end of the Manila Galleon affected the silver distribution patterns: when this took place, the Spaniards were aware of the alternatives already existing, both in America and in the Philippines. As regards to the first, from the end of the 18th century there were occasional trips from the Philippines to the Mexican Pacific (Valdés Lakowsky, 1987, pp. 231–242), and the RCF still engaged in expeditions to Peru until 1820 (Parrón Salas, 1995, pp. 402–407). However, the Philippine alternatives and in particular, the ability of Spanish houses to fundraise from investors in Manila, were definitely the trump cards held by the Spanish firms in Canton, contrary to what has been assumed by some of the few studies dealing with the Western trade in China, in which access to the American market is given greater importance (Dermigny, 1964, vol. III, p. 1244; Cheong, 1979, p. 51; Lin, 2007, p. 110). The perilous opium trade increasingly needed a larger financial cushion: at a time when long distance commercial networks were still not fully instituted, access to capital in the nearby Philippines was of decisive importance for the evolution of the sector. In addition, Manila was to be used at certain times as a market for selling and redistributing opium.

Using the Spanish flag also had certain strategic advantages, opening doors to places the British could not access, namely, Macao (Macau) and Xiamen (Amoy). From the time of the union of the Iberian kingdoms, the Spaniards had had certain advantages in Macao and more especially, from 1746 their flag was permitted in this Sino-Portuguese enclave. This was to be used as a means to evade the EIC controls in Canton, as the British company tried to comply with Chinese opium prohibitions, in order not to affect its own commercial interests (Guimarães, 1996, pp. 66–72, 169–225, 251–265; Morse, 1926, vol. IV, pp. 14–19). In Xiamen, access to the Spanish flag from Manila was permitted at least since the 17th century, and it was to be used to engage in opium smuggling while navigating into Fujian province without arousing suspicion (Chang, 1983, pp. 266–267; Fu, 1966, vol. I, pp. 170, 182–183; Ng, 1983, pp. 55–59).

Unlike its employees, the RCF would have been reluctant to engage in the opium trade, not for moral reasons but rather for commercial and political-representative concerns. First, speculation and risk of confiscation of an illegal product since the Yongzheng edict of 1729 made this trade insecure. Second, as a chartered company, the RCF had quasi-diplomatic duties, both towards its European counterparts and the Chinese authorities, hence its reluctance to infringe Chinese law. Thus, the factor Agote is sceptical in his diaries when referring to a proposal of exploring the Manila-Xiamen route to sell opium in 1793.8

Agote's successors, however, were more interested in the sector. Before the opium boom in Canton in the first half of the 1820s, the Bengal and China factors would exceptionally introduce the Company into the trade, when the sector convened at Macao, which in turn gave way to the Hispano-Portuguese collaboration. Exemplifying this, in 1810 the Calcutta factors sent a cargo of between 225 and 255 chests to their counterparts in Canton, on two Portuguese vessels, with a profit of about 50,000 pesos or Spanish dollars. The Company's Board of Administration, however, manifested some reserves as it was a business ‘exposed to forfeiture’ (‘expuesto al confisco’).9 At the end of 1811, the factor Francisco Mayo in China interceded in favour of the Macanese Manuel Pereira, who applied for the drawing of EIC bills on Bengal in advance for 50,000 pesos, with the deposit of 100 chests of Patna opium as security (Morse, 1926, vol. III, pp. 161–163). In November 1819, Miguel de Arriaga Brum da Silveira, Desembargador Ouvidor of Macao, sought advice from the RCF's representatives about the Portuguese proposal of negotiation submitted to the EIC, during the dispute with the British because of their policies against Malwa opium. The Spaniards, with Lorenzo Calvo already in China as a factor, expressed their approval (Guimarães, 1996, pp. 54, 259–260).

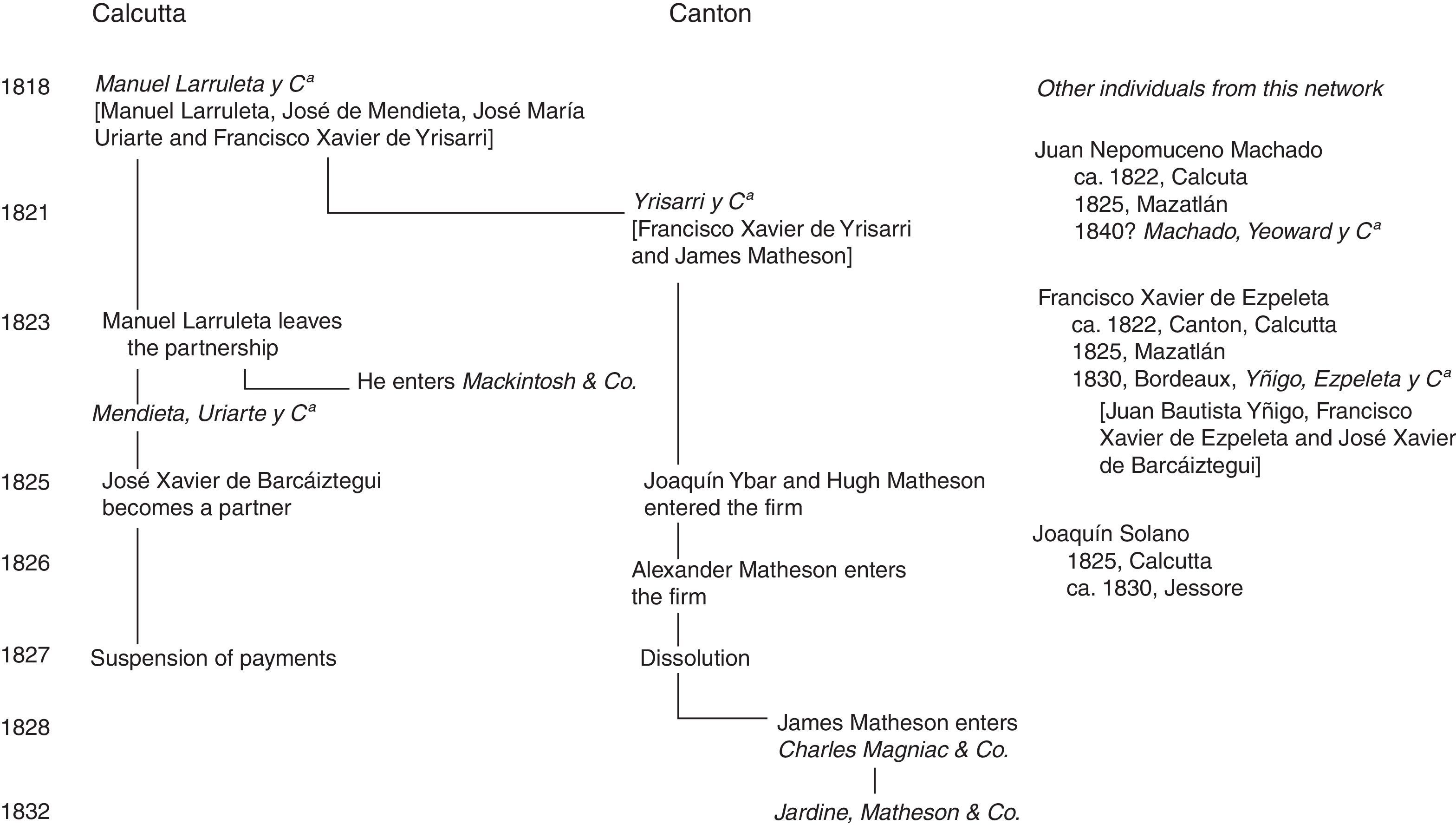

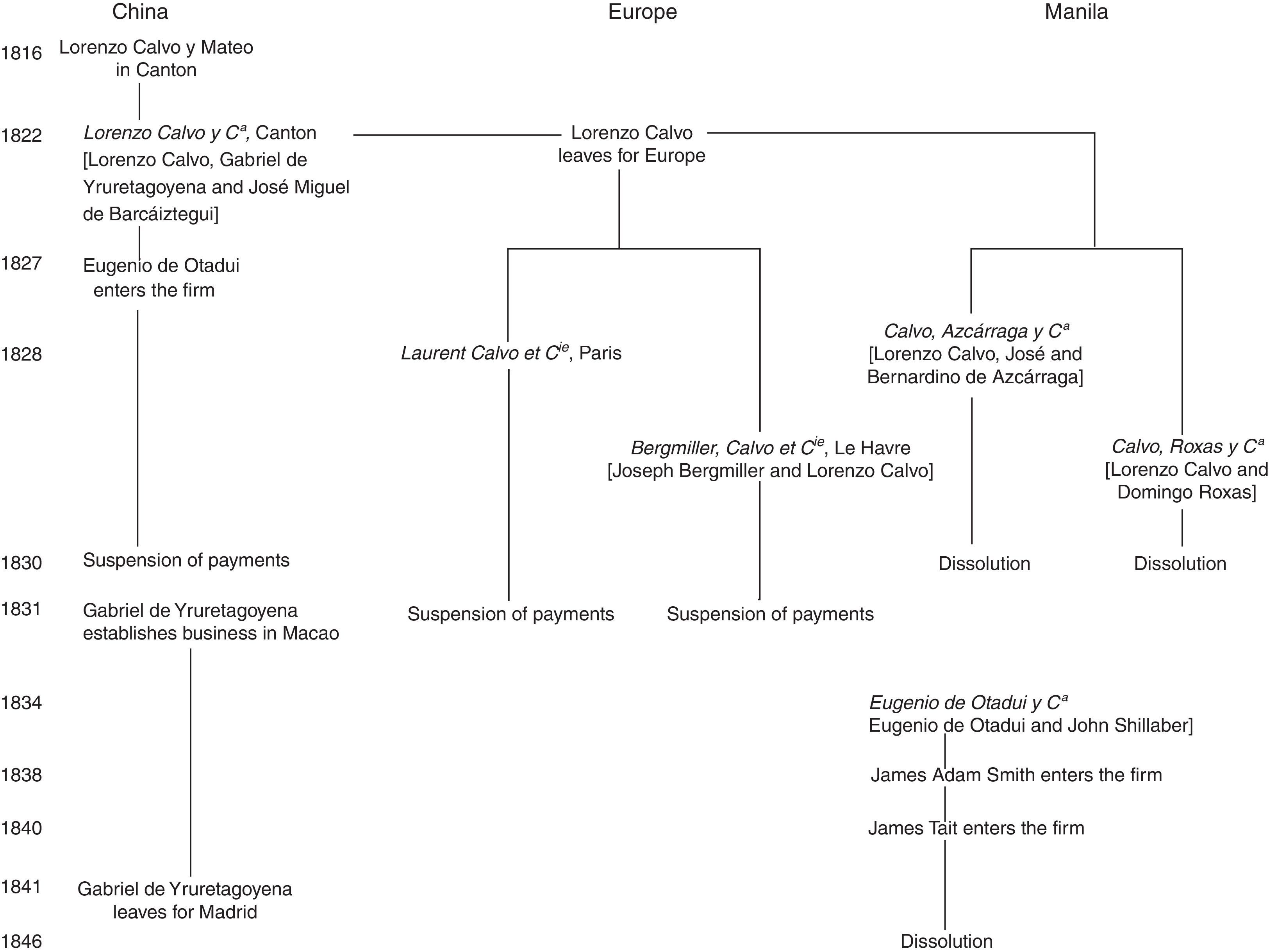

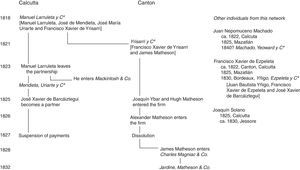

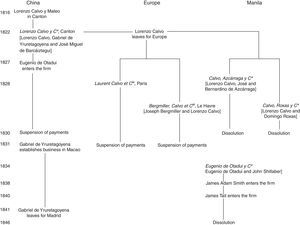

4The Calcutta and Canton networksAround the RCF factories in Calcutta and Canton, the two groups in the Spanish sector of this trade were formed. Here we use ‘Calcutta’ and ‘Canton network’ to refer to the groups that originated from the respective Spanish factories (see Figs. 1 and 2). These two networks began competing with each other and subsequently ended up cooperating closely.

In Calcutta, the factor Manuel Larruleta, after resigning from his post in the factory, established a private firm in 1818, Manuel Larruleta y Ca. Other RCF employees, José de Mendieta and José María Uriarte, as well as the junior employee Francisco Xavier de Yrisarri, became part of the firm. This was tied to the interests of the British house Mackintosh & Co., one of the main houses of the indigo sector which also had interests in the acquisition of opium for its sale in China. The RCF factory business intermingled with private concerns, both Spanish and British. For instance, the last trip of the RCF to Peru in 1819–20 was made on board the British corvette Merope, which was often used by Larruleta y Ca/Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca and Yrisarri y Ca. Eventually for reasons not known, Larruleta gave up the partnership in 1823, when it changed its name into Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, and joined Mackintosh & Co. In 1825 a new partner, José Xavier de Barcáiztegui, San Sebastian-born and also an employee of the RCF, entered the Spanish firm in Calcutta.10

The interests of both Larruleta y Ca and Mackintosh & Co. in the opium business led them to set up a branch in China in June 1821 for the consignment of opium purchased in India. This bore the name of Yrisarri y Ca and was made up of the aforementioned Francisco Xavier de Yrisarri and James Matheson, who came from the Mackintosh family and who had previously worked in Macao in the firm of Robert Taylor & Co. Choosing a non-English name for the house, more familiar to potential customers in the Philippines, may give some clues about the projects the new firm had in mind, and attests to the importance of the connections with the Spanish colony during this period of the Western trade in China. In 1825 two new members joined the house, Joaquín Ybar, also from San Sebastian, and Hugh Matheson, followed by Alexander Matheson in 1826, both nephews of James.11

Other individuals played a role inside the Calcutta group. Francisco Xavier de Ezpeleta, Yrisarri's cousin and with no documented connection with the RCF, had been an apprentice in Robert Taylor & Co. and appears in the Calcutta network entourage together with Juan Nepomuceno Machado, from Manila. Both of them engaged in various businesses between Calcutta, Canton and Manila. Another member of this network was Joaquín Solano, who led Yrisarri y Ca expeditions to the Fujian coast between 1823 and 1825 for the distribution of opium, and of whom we know very little – even though there are some mentions of a Solano family, from Málaga (Andalusia), owners of indigo plantations in Bengal from 1840.12

When Yrisarri arrived in Canton, the opium business was dominated by the factor of the RCF in China, Lorenzo Calvo y Mateo, a native of Aragon, who acted with no established private firm and very likely had a solid network based in the Philippines. He also had various shared interests with Charles Magniac & Co., for the storage and distribution of opium between Macao and Canton. Calvo stands out as having few scruples over obtaining a monopoly in the sector, bribing and lying if necessary, and having taken advantage of the inaction of the three main British houses in the opium business: Beale, Shank & Magniac – direct precursor of Magniac & Co. – W.S. Davidson & Co. and Robert Taylor & Co.13

In November 1822 and after the cessation of activities of the RCF China factory in the previous year, Calvo left China after establishing a partnership, Lorenzo Calvo y Ca, together with the Philippine creole Gabriel de Yruretagoyena and the junior employee José Miguel de Barcáiztegui – brother of the aforementioned José Xavier. There is no further trace of him until he is established in Paris from at least September 1827, and from where he will develop a wide-reaching network between Europe and Asia. In Paris he set up Laurent Calvo et Cie, together with a branch in Le Havre, Bergmiller, Calvo et Cie, while in Manila there were two firms in which he was also a partner, Calvo, Azcárraga y Ca and Calvo, Roxas y Ca. Thus, he devoted himself to trade between Europe and the Philippines, investing together with the prominent Roxas family in the Philippine manufacturing sector, while the China house focused on the opium trade and banking activities. In 1827, a new partner entered the China firm, Eugenio de Otadui, from Gipuzkoa, a nephew of José Agustín de Lizaur, from the firm of Lizaur, Mariátegui y Ca, one of the main correspondents of Calvo in London.14

All in all, most of these initiatives were launched by Basques. Most of the members of the commercial world of the Spanish empire were of Basque origin, and the RCF was also deeply rooted in the Basque Country, the RCF being a restructuring of the former Royal Gipuzkoan Company of Caracas (Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas) (Aragón Ruano and Angulo Morales, 2013; Gárate Ojanguren, 1990). Most of them were proficient in English – as they had been educated in England – and were to move freely in the commercial world of the British Empire, thus the Hispano-British interaction in this phase of the opium trade.

5Development of the Spanish involvementThree phases can be discerned in the activities of the Spanish firms in the opium trade. For the first phase only fragmentary information can be obtained from the documents studied and point to initial activities of the factors Larruleta and Calvo, just after the end of the Manila Galleon, during the final years right before the closure of the RCF factory in China in 1821. With the establishment of Yrisarri y Ca in this year the second stage began, at the same time the opium boom in Canton unfolded, while great competition, speculative practices and Qing anti-opium campaigns taking place. From this period Spanish activities can be more easily reconstructed as Yrisarri y Ca correspondence books are preserved. The third one, from 1825 until the end of the Spanish houses during the second half of the decade, was a period of stability, activity expansion and interaction between both networks, in which a search for business financing sources and new concerns beyond Asia took place.

From the first stage we have found only isolated details which do not permit us to reconstruct activities. The command of Spanish houses in the opium sector when the second phase began, however, may be an indicator of previous knowledge on the part of the Spaniards as a continuation of former decades of business practice. The good results in the season 1821–22 increasingly attracted more actors to the opium business, but, together with the good perspectives, the risks increased as a result of speculative practices encouraged not only by British but also Spanish firms. The sector was then also suffering from the EIC policies to control the competition from Malwa opium. Thereby in the following three seasons, a total stagnation of the opium market, a fall in the prices and their dramatic fluctuation took place in succession.

Along with the opium boom, Chinese official campaigns against opium ensued, gaining new vigour when the Daoguang emperor came to the throne in 1820. The Spanish firms did not hesitate to use all means possible to dodge the controls, bribing Chinese government servants, and maintaining big floating depots – until then an exceptional resource – which were hidden in Jinxingmen (Cumsingmun), Hong Kong island and especially in Nei Lingding (Lintin) island, around which the so-called ‘Lintin system’ subsequently developed. Among these vessels were Calvo's Spanish brig General Quiroga or the Calcutta corvette Merope, kept by Yrisarri y Ca along with the Spanish brig San Sebastián.

With the Canton opium trade at a standstill and official Chinese persecution, the exploration of alternative markets was envisaged, namely, Macao, Fujian and Manila as already mentioned. Spanish contacts with Macanese firms were huge; however, the enclave was not a suitable way out of the impasse due to the resistance of the dwellers, angry at the loss in favour of the British of a business that previously flourished in the city, and also because of the hesitant policies of the Portuguese authorities, by then divided due to the liberal revolution in the metropole (Guimarães, 1996, pp. 66–72, 169–225, 251–265). Hence new possibilities had to be explored. Between 1823 and 1824 several expeditions to the Fujian coast to experiment with opium distribution were led by Yrisarri y Ca. They started with the first voyages of the San Sebastián (years later to become Jardine, Matheson & Co.’s prominent opium depot Virginia),15 commanded by Joaquín Solano, an example soon followed by the competitors. There were also endeavours to resort to Manila as a sales and redistribution point, aimed at the Fujian junk trade, after a decree by the colonial government in 1823 by which the deposit of opium was permitted in the Manila Customs for its re-export, with a tax of 2%. Yrisarri y Ca sent several consignments of opium for its sale to the Basque trader José de Azcárraga, but the scheme did not take hold, very likely due to the instability in the colony during the Liberal Triennium, and more specifically to the riots in October 1820, the Bayot conspiracy in Spring 1822 and Andrés Novales mutiny in June 1823 (De Llobet, 2011, pp. 225–284).16

Finally, in the third stage, the Canton market reactivation and the increase of business was a way out from the problems of the previous stage. The private firms transcended the mere agency business and started new initiatives with new products, and branched out further. Yrisarri y Ca, for instance, had twenty-four correspondents in Calcutta, four in Bombay (Mumbai), six in Singapore, four in Batavia, one in Penang and another one in Pondicherry (Puducherry).17 Leaving behind the ferocious competition of the previous stage, there was a major interaction among private firms, both British and Spanish. More credit to avoid the opium business risks was sought; in Canton and Calcutta more funds raised from Manila; little local investors were resorted to in India and from Calcutta substantial advances were sought from the China houses. These, in turn, financed the opium consignments that were sent to them from India. Thus, for instance, Calvo y Ca lent 282,668 pesos for their opium operations to Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca between the middle of 1824 and the beginning of 1826.18 In China, the Spanish houses cooperated in the opium floating depots maintenance and distribution, and they also tendered financial and insurance services to the Manila investors. Also as a result of this expansion, from 1825 there were new concerns in the Mexican Pacific started by the Calcutta network. Some Chinese textile shipments to England were tried as well. In the same period, from 1827, the group of Lorenzo Calvo y Ca launched the business enlargement previously indicated between France, China and the Philippines.

All things considered, the total picture of the Spanish involvement in the opium trade is not easy to provide. Available data is partial and not homogeneous; the accounts of Yrisarri y Ca in the Jardine Matheson Archive are not completely accessible to the researcher, and reconstructed figures from the correspondence are discontinuous. Besides, Spanish activities intermingled with the British ones, as they collaborated very closely and received consignments and funds from firms of different nationalities, thus making it very hard to discern a ‘Spanish’ portion of this trade – if such a thing can be defined in terms of nationality.

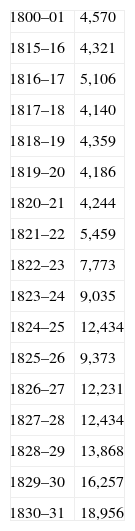

However, some partial figures might be given as representative of the magnitude of the businesses of these houses, and we can assert that roughly around a 20% of the trade carried on in Canton pertained to Yrisarri y Ca, as we can infer from some numbers from its correspondence and from the EIC India bills it purchased. Unfortunately, data from Calvo y Ca are still more fragmentary so no similar estimate can be put forward. In Table 1 a total of opium imports in Canton is given where an increase during the first half of the 1820s can be perceived.

Opium imports into Canton (in chestsa).

| 1800–01 | 4,570 |

| 1815–16 | 4,321 |

| 1816–17 | 5,106 |

| 1817–18 | 4,140 |

| 1818–19 | 4,359 |

| 1819–20 | 4,186 |

| 1820–21 | 4,244 |

| 1821–22 | 5,459 |

| 1822–23 | 7,773 |

| 1823–24 | 9,035 |

| 1824–25 | 12,434 |

| 1825–26 | 9,373 |

| 1826–27 | 12,231 |

| 1827–28 | 12,434 |

| 1828–29 | 13,868 |

| 1829–30 | 16,257 |

| 1830–31 | 18,956 |

Amounts from Trocki (1999, p. 95).

In September 1822, Yrisarri y Ca possessed about 1546 opium chests, almost 20% of the total imports in 1822–23, 7773 chests – besides Magniac & Co.’s 850 piculs19 of Daman opium on board Calvo's General Quiroga. In the beginning of the following season, in April 1823, the Hispano-British firm had 1668 chests in hand, of which 1288 were on board several vessels around Canton: 898 on the Merope, 140 on the General Quiroga, besides 250 on the Portuguese Constituição. In addition they had 380 chests in Macao. This represents 21.45% of the above mentioned 7773 chests of the previous season.20 It should be born in mind that the opium business was then dominated by two British houses, besides the two Spanish ones and three Parsi firms.

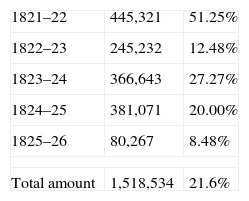

Another sign, again fragmentary, giving a picture of the Spanish proportion of the opium business is the use of EIC's India bills, which were used to send the proceeds from Canton to Calcutta. Yrisarri y Ca purchases amounted to 21.6% of the total of the China houses in the period between 1821 and 1826, as it is shown in Table 2. The second column indicates the total amount seasonally purchased by Yrisarri y Ca, while the third indicates what percentage this is of all the bills purchased by all China houses together.

Purchase of EIC bills on India by Yrisarri y Ca (in pesos).

| 1821–22 | 445,321 | 51.25% |

| 1822–23 | 245,232 | 12.48% |

| 1823–24 | 366,643 | 27.27% |

| 1824–25 | 381,071 | 20.00% |

| 1825–26 | 80,267 | 8.48% |

| Total amount | 1,518,534 | 21.6% |

Amounts from Cheong (1979, p. 101).

Besides this 21.6% of Yrisarri y Ca, Magniac & Co. purchased 39% of these five seasons’ India bills; Dent & Co., 26.4% and the three Parsi houses, the remaining 13%.

6Philippines and MexicoThe Philippine connection was the hallmark of the Spanish private firms: yet the Philippines have been totally cast into oblivion in the accounts of foreign trade in China. Direct access to American silver, for not a few historians perceived as the main asset of the Spaniards, was, on the contrary, problematic during that period of transition. There were indeed some contacts between the two shores of the Pacific then: we have already mentioned the RCF expeditions to Peru until 1819–20, and probably the acquaintance with the existing alternatives to the Manila Galleon, developed by the Manila firms before its end, was greatly advantageous. However, these trans-Pacific concerns between 1822 and 1825 (when major documentary evidence has been found), were not substantial, and were not as significant as the Philippine ones.

Opium investments increasingly needed more credit to face their uncertainties. Yet at that time means of long-distance capital transmission – especially to the American and British financial markets – were not fully developed by all the private houses, thus closer Philippine capital was an asset in this period of expanding activities. However, these were isolated from international trade networks. After the end of the Galleon and the decline of the RCF, the Philippine capital was in search of investment: part of it went to Spanish houses in China, to be allocated in respondentia bonds – being thus a continuation of the obras pías of the Galleon – mainly given to Macanese shipowners, which gave the Manila investors high benefits of a yearly 20%. It was also allocated to a lesser extent in time deposits of a benefit of about a yearly 10%.

Due to the dispersal of data in the correspondence, no total sum of the funds from Manila can be provided, yet there are a few some examples. In the beginning of 1823, the creoles José Coll and Manuel de Olea, for instance, had invested in Yrisarri y Ca 8632 and 5755 pesos respectively, and at the end of 1824, their capital was of the order of 13,264 and 12,310 pesos.21 Among others, the names of Juan de Córdova, Baltasar Mier, Manuel de Revilla, Yñigo González de Azaola or Dolores de Yruretagoyena – cousin of the manager of Calvo y Ca in China – stand out. Philippine capital not only went to investment funds used as correspondentia bonds, but also to the loans demanded from opium firms and especially, from Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca. In addition, Manila capital was also used for the investments of the China houses in the Mexican Pacific from 1825. In that year, Ventura de Pereda, Manuel de Revilla and Dolores de Yruretagoyena are the most prominent lenders, the first one advanced 12,000 pesos, 18,000 each the other two, to which we should add some extra 24,000 pesos lent by the two of them together.22

These capital movements show the extent of Manila firms’ networks, then expanding just immediately after the dismantling of the Galleon, as described by Legarda (1999, 2002). Philippine economy was then evolving to a new export model based on plantation products, gradually being implemented from the last third of the 18th century (Fradera, 2005, pp. 475–486). There are signs that before the ascent of foreign initiatives and the definite closure of Mexico to the Spanish subjects, creole firms developed trading activities in the region and on the American Pacific shore as well. China houses are an indication of this dynamism: not only did they supply products for this trade and receive consignments from Manila – thus maintaining a service already offered by the RCF from Canton since 1790 – they also provided services lacking in the colony such as insurance and banking, apart from international financial information transfer. For example, Yrisarri y Ca took the consignments from firms like Yrastorza, Brodett y Ca, mainly of sugar and Luzon rice but also indigo, fragrant woods, cigars and foodstuffs intended for Chinese consumption – such as sea slugs, bird's nests or shark's fins among others – on the other hand, they provided textiles, sulphur, lead, saltpetre and occasionally tea in return.

The breakdown of the trans-Pacific link also affected private Philippine interests, mainly after the prohibiting in 1820 of Spanish subjects from trading with the new republics, and particularly after Agustín de Iturbide's seizure in February 1821 of 525,000 pesos from the frigate Santa Rita, of the Manila commerce, coming from San Blas (Valdés Lakowsky, 1987, pp. 289–292). Manila firms would have then turned to China as a location for the transfer of goods which then, from China could be sent to Mexico. However, this recourse seldom appears in the correspondence. Rather, there are references to the ‘not too propitious prospects’ (‘semblante poco favorable’) of these ventures in the beginning of the 1820s.23 It is not until 1825 when Yrisarri y Ca, together with Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca reconsidered trans-Pacific trade, establishing contacts in Mexico that were not related to the colonial period. This took place while Guadalupe Victoria's administration launched measures to attract trade, namely, the opening of the ports of Mazatlán (Sinaloa) and Guaymas (Sonora) in 1822 and 1824, and the exemption applied to Sinaloa and Sonora to the prohibition of silver exports also in 1824, to which we may add the Spanish decree in the middle of the decade that allowed American money circulation with a surcharge of 0.5% (McMaster, 1959; Valdés Lakowsky, 1987, pp. 293–294; Heath, 1993). In this way, the firms of the Calcutta network set the basis for the trade of Asian textiles for American silver, of which the Merope expedition to Mazatlán in 1825 was the most prominent example, again with broad involvement from Manila interests apart from Spanish individuals established in Calcutta.24 Francisco Xavier de Ezpeleta and Juan Nepomuceno Machado took up residence in Mexico and carried out significant business with the influential Mexican-British firm of Barron, Forbes y Ca of Tepic (Nayarit).25

7The end of the Spanish firmsThe extension of new activities in the middle of the 1820s entailed an increasing financial vulnerability for the Spanish firms involved in the opium trade. The excess of concerns, a major interdependence and also, the debt of the RCF to its employees threatened the continuity of these houses.

Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca suspended payments in the spring of 1827, leaving a total debt of a million and a half pesos. This also compromised the financial situation of Yrisarri y Ca, which managed to balance their accounts before James Matheson dissolved the partnership. The Spanish Calcutta firm acquired too many compromises not only with Yrisarri y Ca and Lorenzo Calvo y Ca, but also with Mackintosh & Co. besides many Manila investors. As employees of the RCF, the factors Mendieta and Uriarte had advanced their own funds for the Company's speculations, the refund of which the Spanish chartered corporation ignored due its many financial issues. This in turn affected Mackintosh & Co., also suppliers to RCF concerns. The Calcutta network ruin was triggered by the Calcutta financial crisis of 1826. This was a result of credit abuse, over-speculation in India produce from England and a long-standing lack of liquidity, a situation aggravated by the processes of independence in America, the indigo crisis and the emergence of Bombay. In addition, the China opium sales slowed down in the season of 1826–27 (Cheong, 1973).26

This situation coincided with the death of Francisco Xavier de Yrisarri in the autumn of 1826 and the lawsuit – in the end unfounded – from Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca to the estate of the deceased, to whom the Calcutta house demanded for the loss of some pending speculations when he left Manuel Larruleta y Ca. After settling an agreement with the many Manila creditors of the Calcutta firm and dissolving Yrisarri y Ca, James Matheson finally joined Charles Magniac & Co. at the beginning of 1828, which in July 1832 became Jardine, Matheson & Co. His nephew Alexander would join the firm as well, while Hugh would establish Lyall, Matheson & Co. in Calcutta in 1831. Joaquín Ybar entered Dent & Co., but the references to his activities are scant until he left for Europe in 1833.

Although probably a strong creditor of Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, Lorenzo Calvo y Ca seemed little affected. Furthermore, the activities of Lorenzo Calvo's Euro-Asian network were deployed to their maximum extent during these years until the firm's dissolution between the end of 1830 and the beginning of 1831. An excess of speculations and also a heavy debt owed by the RCF, of 542,000 pesos, sentenced the situation of Calvo's manifold interests. The Paris house leant too much on China: just before the suspension of payments at the end of 1830, the quantity indebted to the China house amounted to 155,000 pesos, to which we should add nearly 100,000 owed by Liu Zhangguan ‘Chunqua’, of the Dongsheng hang. At the same time, the Manila partnerships were also dissolved and in the spring of 1831, those of France followed. Added to all this, Calvo's own political commitments worsened his financial situation: in 1830 he organised in Paris a public loan to finance José María de Torrijos expedition against Ferdinand VII of Spain's absolutist government, in which Calvo himself invested 105,000 pesos. He was thereby sentenced to death and his properties were confiscated. He was, however, finally amnestied in 1833. Not too long after he sued the RCF in 1835 and won the cause.27

Beside all these particular difficulties, the evolution of the opium trade by the 1830s hindered the viability of the Spanish initiatives. More credit was needed and with it, wider connections to international financial networks and command of the new financial devices, besides an extensive logistical and human resources deployment, processes which were parallel with the Anglo-American hegemony in international finance and trade. However, the houses here analysed started an evolution in this direction as already noticed, even though they did not withstand the financial crisis in Asia from 1826 onwards. In addition, a reshaping of the trans-Pacific connection and of the Philippine economic model took place. Here, foreign initiatives toppled the local ones, and capital formerly invested in the China houses was re-oriented to the domestic economy, while US and Britain sources of finance were used from the continent. Services previously sought in Canton were no longer required in Manila as they developed in the colony. Lastly, the disappearance of the RCF and of the EIC definitely put an end to a complex Hispano-British network that had been seminal for the Spanish opium initiatives, and more specifically, the absence of a Spanish factory in Bombay deprived it of a decisive contact in one of the crucial ports in the reshaping of the opium trade in the 1830s.

Still, there would be some continuity, provided by Jardine, Matheson & Co., a continuation of both the Calcutta and Canton networks. The Philippine and Mexican contacts of James Matheson were added to the ones that Magniac & Co. already had, Calvo y Ca among them. Gabriel de Yruretagoyena and Eugenio de Otadui remained active in the entourage of the British firm until the 1840s. Yruretagoyena took up residence in Macao until 1841 when he left for Madrid. In Macao he engaged in several businesses between the enclave and Manila, opium speculation being one of them. He also acted as a Spanish Commercial Agent in China from 1830. Otadui set up in 1834 the Manila agency of Jardine, Matheson & Co. – Eugenio de Otadui y Ca – together with an American, John Shillaber. They worked in the field of Philippine plantation exports, mainly rice, sugar and tobacco, to China, the US and Britain (Tarling, 1963). In 1840 the Scotsman James ‘Santiago’ Tait entered the firm; in 1846, after the house dissolved, he appears as a Spanish vice-consul in Xiamen, where he also engaged in coolie trade to Cuba (Martínez Robles, 2007).28

While Philippine investors gradually retired from the British firm contacts, Jardine, Matheson & Co.’s ventures in Mexico, started by Yrisarri y Ca, were developed. Contacts with Juan Nepomuceno Machado in Mazatlán and his firm of Machado, Yeoward y Ca, and also with Barron, Forbes y Ca, were maintained. Francisco Xavier de Ezpeleta established himself in Bordeaux in 1830 and set up the firm of Yñigo, Ezpeleta y Ca, one of whose partners was José Xavier de Barcáiztegui. The company attracted Basque capital which was sent from Mexico after the expulsion of the Spaniards in 1827 (Ruiz de Gordejuela, 2006), and it invested in long distance trade and shipping. In 1830 it obtained a charter from the Spanish government for the operation of the Almadén mines, which it held until 1835 when this was transferred to N.M. Rothschild & Sons. The latter passed some part of the returns to the house of Bordeaux. The Rothschilds were important lenders to the Spanish liberal government: their loans were returned in orders of payment against the colonial budgets, namely those of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines – where Otadui y Ca were in charge of collecting the returns and passing them on to their beneficiaries (De Otazu, 1987; López-Morell, 2005).29

As regards the opium trade, some practices begun by the Spaniards together with the British in the previous decade were followed and expanded. Thus, floating depots were kept around Canton and the ‘Lintin system’ was developed. Extensively armed fleets distributed opium along the Chinese coast, and Manila was occasionally used as a redistribution point. When the Opium War broke out in 1839, Eugenio de Otadui y Ca were in charge of receiving Jardine, Matheson & Co.’s opium stock, diverted to Manila due to Lin Zexu's campaigns, until the summer of 1840, while some Philippine individuals also commissioned opium shipments to China.30

8ConclusionVarious aspects of the Spanish initiatives in the opium trade should be pointed out. First, their transitional character, as they took place after the end of the Manila Galleon and during the RCF crisis until 1830, being in a half-way point in the development of Western trade in East Asia, between the dominance of chartered companies and the consolidation of private initiatives. Second, their relatively short duration, as Spaniards faded away from private Western trade in China with the end of the RCF and its logistics, together with changes in the Asian and trans-Pacific trade, in the Philippine economy and in international trade and finance networks, in which the Spaniards could not compete. Third, they resulted from a Hispano-British collaboration, where the Spaniards provided benefits such as knowledge of alternative silver sources, access to the Philippines and more specifically, to its capital, and the use of the Spanish flag in South China coast. Thus, we can state that without Spanish houses’ activities no accurate assessment of the evolution of the foreign private trade during the first decades of the 19th century in China can be made, as they were actors at a crucial moment of transition, little known, in the evolution of Western trade in the 1820s, when the grounds for the practices of the 1830s, inherited by Jardine, Matheson & Co., were established.

With this material, we contribute to a still necessary redefinition of the whole of the opium trade in China, a critical element in all studies concerning Qing China, commerce and imperialism. A relevant Spanish component existed in foreign trade in China not only in the 19th but also 18th and earlier centuries, and this entails assessing all variations and polyphony that pervaded this trade. Apart from the India–China routes, other regional and international currents converged in Southern China, most of these from the Pacific sphere, which had a strong Spanish component. Its constituents were not only the Manila Galleon but also its alternatives, the still too unexplored Philippine link in China and in India, and the activities of the RCF.

I am deeply grateful to my PhD supervisors, Josep Maria Delgado Ribas and Dolors Folch Fornesa, for their aid and confidence. I also must express my wholehearted gratitude to Josep M. Fradera, Carlos Martínez Shaw, María Dolores Elizalde, Manel Ollé and Zheng Yangwen for their kind support and help.

This work introduces the key aspects of my PhD thesis (Permanyer-Ugartemendia, 2013).

Ramón Carande Award, Edition XXVII (Call 2013), Spanish Economic History Association.

Spanish documents from the National Archive of the Philippines can be consulted in microfilm in the Instituto de Historia of the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Madrid.

About the Jardine Matheson Archive, see Le Pichon (2006); concerning Jardine, Matheson & Co., Greenberg (1951), Cheong (1979) and Le Pichon (1998).

Due to space limitations, only the most relevant documents are mentioned here.

The three Parsi firms of Cursetjee Framjee, Merwanjee Manockjee and Framjee Muncherjee should also be mentioned.

The Spanish supply in Canton was never the most significant: this was the US from the end of the 18th Century (Irigoin, 2009, p. 211).

See also Alexander's East Asia and Colonial Magazine, 1835, vol. IX, pp. 596–597; vol. X, pp. 241–248, 273–278, 571–576.

Manuel de Agote, Canton diary, August 1793, Untzi Museoa, Fondo Manuel de Agote R-635.

The acquisition cost of the opium in Calcutta had been of about 200,000 pesos, more specifically, of 3,959,196 reales de vellón and one maravedí. Minutes of the Board of Administration of the RCF, 13th of December 1811 & 21st of January 1812, Archivo General de Indias (hereafter, AGI) Ultramar, 640; Financial Statement 1805–1813, 30th of March 1815, AGI Filipinas, 993.

Financial Statement of the RCF of 1818, 31st of December 1819, AGI Filipinas, 994; Minute of the Board of Administration of the RCF, 12th of August 1825, Filipinas, 983; Yrisarri y Ca to Larruleta y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 19th of April 1823; to Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 26th of April & 29th of July 1823; Jardine Matheson Archive (hereafter, JMA) C2/2; Yrisarri y Ca to Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 3rd of October 1825; C2/4. See also Cheong (1979, p. 57).

Circular announcing the establishment & Deed of partnership of Yrisarri y Ca, 1st of July & 10th of October 1821, JMA L11/1 & F10/1; James Matheson to José Antonio Fernández, Canton-San Sebastian, 15th of January 1827, C2/5.

Yrisarri y Ca to Francisco Xavier de Ezpeleta, Macao, 13th of July 1823, JMA C2/2; to Juan Nepomuceno Machado, Canton-Calcutta, 8th of October 1822, C2/1; James Matheson to Joaquín Solano, Canton-unplaced, 26th of March 1824; B7/2 no. 25; O’Malley (1906, pp. 199–200).

Yrisarri y Ca to Larruleta y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 10th of April 1822, JMA C2/1; Cheong (1979, pp. 56-57).

Yrisarri y Ca to Lorenzo Calvo, Canton, 27th of October 1822, JMA C2/1; Magniac & Co. to Calvo, Azcárraga y Ca, Canton-Manila, 1st of October 1828, C10/9; Calvo y Ca to Magniac & Co., Canton, 18th of April 1827, B7/2 no. 112; Bottin du Commerce, Archives de Paris PER 292, 1828 to 1833; Deed of partnership of Bergmiller, Calvo et Cie, Paris, 1st of March 1828, D31 U3 36 (2nd of January–10th of May 1828); Agreement between Calvo & Roxas, Archivo Histórico de Protocolos Notariales de Madrid, no. 25559; I am deeply grateful to Martín Rodrigo Alharilla for this reference.

In September 1839 a Chinese patrol, mistaking it for the Virginia, boarded the Spanish brig Bilbaíno and burnt it down, one of the casus belli for the war (Waley, 1958, pp. 74-75). Perhaps the Chinese authorities still had in mind the former San Sebastián – therefore the mistake was not as serious as might be inferred. Jardine, Matheson & Co. to John Shillaber, Canton-Manila, 10th of February 1834; to Eugenio de Otadui, Canton-Manila, 5th of June 1834, JMA C10/17.

Yrisarri y Ca to Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 26th of April, 29th of July & 24th of September 1823; to José de Azcárraga, Canton-Manila, 4th of December 1823; JMA C2/2.

Circular of Yrisarri y Ca, 5th of June 1824; JMA C2/3.

Calculated from several letters of Yrisarri y Ca, mainly to Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, JMA C2/3 to C2/5.

A picul (or dan) amount to 60kg and it is generally used in Western India opium varieties.

Yrisarri y Ca to Larruleta y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 1st of September 1822; to Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 26th of April 1823; JMA C2/1 & C2/2.

Yrisarri y Ca to José Coll & to Manuel de Olea, Macao-Manila, 27th of January 1823 & 6th of March 1824; Canton-Manila, 20th of July & 31st of December 1823; to José Coll, Canton-Manila, 30th of March 1824; JMA C2/1, C2/2 & C2/3.

Yrisarri y Ca to Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 24th of September 1825, JMA C2/4. Some of these creoles’ names can be found in De Llobet (2011).

Yrisarri y Ca to Nicolás de Molina, Canton-Manila, 22nd of September 1822, JMA C2/1.

Again, due to data dispersal in the correspondence we cannot provide total amounts.

Yrisarri y Ca to Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 2nd of May, 14th and 18th of June 1825, JMA C2/4.

James Matheson to Mendieta, Uriarte y Ca, Canton-Calcutta, 3rd of March 1827; to José Antonio Fernández, Calcutta-San Sebastian, 4th of June 1827; to José de Azcárraga, Canton-Manila, 26th of September 1827; JMA C2/5; Report of Lorenzo Calvo about the RCF, 5th of August 1828; Baudin, Etesse et Cie affair file, 9th of September 1828, both in AGI Filipinas, 996.

Calvo y Mateo (1835); Gabriel de Yruretagoyena & Eugenio de Otadui to Lorenzo Calvo, Macao-unplaced, 27th of May 1830, Newberry Library, Ayer MS 1932; Lorenzo Calvo's properties’ confiscation file, 4th of January 1832, AGI Filipinas, 520.

Gabriel de Yruretagoyena to Magniac & Co., Macao-Canton, 4th of July 1831, JMA B7/27 no. 519; Jardine, Matheson & Co. to Otadui y Ca, Canton-Manila, 6th of April 1835, C10/19; to James Tait, Hong Kong-Xiamen, 2nd of January 1847, C13/4; Enquiry of the Captain General Luis Lardizábal to the Secretary of State, Manila, 29th of May 1839, Archivo del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, H-2956 exp. 1.

Circular announcing the establishment of Yñigo, Ezpeleta y Ca, Bordeaux, 1st of January 1830, JMA B6/7 no. 30; Jardine, Matheson & Co. to Otadui y Ca, Canton-Manila, 6th of August 1836, C10/21.

Jardine, Matheson & Co. to Otadui y Ca, Canton-Manila, 11th of March 1839; circular of Jardine, Matheson & Co., 22nd of June 1839; JMA C10/25.