This investigation analyzes a sample of 332 Spanish teenagers following different academic careers and the relationship among four emergent cognitive concepts in positive psychology: dispositional optimism, hope, self-efficiency and the sense of coherence. The results indicate statistically significant differences between individuals who have pursued successful academic careers, regardless of the direction towards university or professional orientation, and those who have had unsuccessful academic backgrounds. Furthermore, there are interrelationships between all constructs considered, clearly defining a positive development profile in adolescents, which suggest further research and development of different human performance indicators to promote positive development in adolescents.

En este trabajo se analizan en una muestra de 332 adolescentes españoles con distintas trayectorias académicas las relaciones entre cuatro constructos cognitivos emergentes en el campo de la psicología positiva: el optimismo disposicional, la esperanza, la autoeficacia y el sentido de coherencia. Los resultados ponen de manifesto que se encuentran diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los adolescentes que han seguido trayectorias académicas de éxito, independientemente de su orientación a la universidad u otras preferencias académicas. Por su parte, se encuentran interrelaciones entre todos los constructos considerados, que si bien pueden definir un perfil de desarrollo positivo adolescente, también suponen distintos elementos del funcionamiento humano que hay que conocer y desarrollar para promover dicho desarrollo positivo adolescente.

Positive psychology has greatly expanded in recent years, with a breakthrough in research over the past ten years since Seligman (2002) proposed this new approach to psychology in various forums. A large number of psychological constructs have become widespread through this process, on occasion with extensive development, whereas other constructs have become established more recently. Though the focus does not necessarily pose a revolution in the field of psychology, it has allowed for the resuming of functional aspects and areas of research that denote an important contribution to psychology in areas such as education, to which we refer in this investigation. Accordingly, the concept of positive development in adolescents has emerged in current research in this field. It addresses an area of development from a perspective of the acquisition of competencies rather than issues that arise during adolescence and also stresses the importance of context in the development and progression of this stage (Oliva et al., 2010; Orejudo and Teruel, 2009).

As we have pointed out, this peak in positive psychology refects a variety of emerging constructs, apparent in various manuals of positive psychology (Gilman, Huebner & Furlong, 2009; Snyder & Lopez, 2005). Among these, we considered certain constructs to be useful when addressing this notion of positive development in adolescents, focusing our research on those concepts referring to personal characteristics. Theoretically, these constructs are based on self-regulatory models of behavior and are useful in predicting psychological adjustment. The applicability of this study is paramount in the field of education as it may help identify the elements that constitute positive development and foster suggestions to define competencies for the advancement of educational institutions (Orejudo & Teruel, 2009). In the same way, such constructs provide theoretical guidance for educational research based on positive psychology among adolescents (Orejudo, Puyuelo, Fernández-Turrado & Ramos, 2012).

Following this approach, in this study we analyze adolescent development from the perspective of dispositional optimism (Carver & Scheier, 2005), hope (Snyder et al., 1991; Snyder, Rand & Sigmon, 2005), self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997Maddux, 2005) and complete sense of coherence; novel theoretical contributions in this field of study (Antonowski, 1991; Palacios-Espinosa & Restrepo-Espinosa, 2008). Considering these developments, we analyze to what extent common or differential elements are founded in the behavior of adolescents. Accordingly, collective research demonstrates a high level of interrelationships among these constructs. For example Pacico, Zanon, Bastialello & Hutz (2011) establish this among hope, optimism and self-esteem while Hughes, Galbraith & White (2011) and Sanmartin, Carbonell & Baths (2011) support an interrelationship with self-efficacy. Yet it is unclear if these studies have distinctive theoretical implications (Hughes et al., 2011; Sanmartin et al., 2011). In practice, it is necessary to proceed from a model of personal behavior and comprehend the context that favors such, so as not only to determine the characteristics of positive development, yet also to identify specific conditions that enhance this progress among adolescents.

Hence, in this investigation we will analyze the relationships between levels of optimism, sense of coherence, general self-efficacy and hope of Spanish adolescents following different academic careers. In anticipation we will briefly discuss the theoretical implications of each relationship and the variables that advance their development. We will conclude by reviewing the characteristics presented in formative Spanish training programs, specifically based on the response from students who have not successfully completed preparation courses required for admittance to a university or professional working sector, referred to in this study as Initial Programs of Vocational Qualifica-tion (PCPI).

Theoretical frameworkTheoretically there are two different models underlying the concept of optimism. The first model, dispositional optimism, refers to the expectations that individuals have towards achieving certain goals. These expectations can vary on a wide spectrum from having total optimism, perceiving such goals as attainable to experiencing extreme pessimism, perceiving goals as impossible or very difficult to reach (Carver & Scheier, 2002, 2005). The second model, optimistic attributional style, focuses on attributions that were acquired from past events (Gillham, Shatté, Reivich, & Seligman, 2002; Peterson & Steen, 2005).

Among adolescents, optimism has been associated with increased protection when facing stressful events, decreased depressive symptoms and behavioral issues, in addition to improved adjustment and social competence (Ey et al., 2005; Deptula, Cohen, & Ey Phillipsen, 2006, Cole et al., 2008). Various reviews indicate optimistic relationships with other constructs, particularly with theoretically potential mediators their effects, coping strategies and specific behaviors that emerge in the process of pursuing goals (Carver & Scheier, 2002; Orejudo & Teruel 2009).

Hope is defined as a cognitive construct that poses a double component: agency, the perception of personal trust as an ability to establish necessary resources in order to achieve personal goals and/or pathways, and knowledge of strategies that lead to the attainment of such goals (Snyder et al., 1991). These two elements contribute to persistence when facing conflicts that may arise and seek alternative ways to reach one’s goals.

Embedded in models of self-regulation, self-worth is suggested to represent the cognitive constructs of positive psychology (Snyder et al., 2005). In this way, it is an encouraging resource of positive development among youth (Bronk, Hill, Lapsley, Talib & Finch, 2009; Lagacé-Séguin & d’Entremont, 2010) and is already considered to be a strong predictor of personal wellbeing and adjustment. Furthermore self-worth interacts with the school environmental factors to explain one’s demeanor regarding a certain level of health. Hope predicts personal adjustment beyond essential purposes, a key aspect in the early years of adolescence (Bronk et al., 2009). The importance of this construct is refected in the large number of one’s adaptation to different cultures, as much European as Anglo-Saxon, Brazilian or Latin-American, confirming a relationship with adjustment indicators in such adaptations (Edwards, Ong & Lopez, 2007).

As in the case of optimism, hope predicts the use of different coping strategies, particularly the belief that pathways predict the use of diverse genetic strategies whereas agencies are concentrated on seeking support (Roesch, Duangado, Vaughn, Aldridge, & Villodas, 2010). In the same sense, when development is analyzed from the perspective of personal identity, hope appears as a central element in differentiating adolescents as positive and negative profiles, in such a way that adolescents who demonstrate increased personal development are characterized as having high levels of hope and wellbeing (Burrow, O’Dell & Hill, 2010).

Moreover, Antonovsky (1987, 1991) defines sense of coherence as a relatively stable and healthy orientation of one’s personality, which is based on the ability to assume that life events are predictable, meaningful and manageable, and to be able to convert these into a safeguard when faced with stress. It is understood that this sense of coherence is a universal and cross-cultural construct, therefore important in the adjustment of people residing in different cultures (Braun-Lewensohn & Sagy, 2011). This construct was initially analyzed in relation to health (Moreno, Gonzalez & Garrosa, 1999; Palacios-Espinosa & Restrepo-Espinosa, 2008). However given its active role in maintaining one’s health and in coping with stressors, it could be identified as a new approach to analyze positive development in adolescents, a stage that has also been related to adaptation and as evidenced by several investigations. Accordingly, a sense of coherence predicts negative emotional states such as anxiety and depression found among Scandinavian students (Myrin, & Lagerström, 2008), greater levels found in the case of female rather than male adolescents (Moksnes, Espnes & Lillefjell, 2012). Of the three dimensions of coherence, significance and comprehension have greater relevancy when predicting signs of depression for this age group (Hittner & Swickert, 2010).

Comparably, a sense of coherence is associated with lower consumption of alcohol and tobacco, greater social competence, improved oral hygiene habits (Mattila et al., 2011) and lower levels of stress, including conditions that are deemed to be highly demanding (Braun-Lewensohn & Sagy, 2011). Moreover, Koushede & Holstein (2009) prove that a sense of coherence is a good predictor of self-medication practices in young adolescents suffering from headaches. Within context of academic stress, a sense of coherence also serves as a stress absorber (Modin, Östberg, Toivanen & Sundell, 2011). It is informative how Ristkari et al. (2009) found that a lower sense of coherence is associated with antisocial behavior in male adolescent Finnish students. In other cultural contexts, a sense of coherence might be a suitable mediator of influential family factors in the appearance of behavioral problems.

Bandura defines self-efficacy as the judgment people construct of themselves in relation to their abilities to organize and execute behaviors in order to achieve certain outcomes (Bandura, 1997). Through one’s perception of self-efficacy, people construct motivational strategies to successfully achieve personal goals. Currently, it is considered that it may be a useful theoretical framework to study one’s wellbeing (Reyes-Jarquín & Hernandez-Pozo, 2011) and also to analyze the positive development of adolescents (Sanmartin et al., 2011).

Considering the school context, students with high perceptions of self-efficacy show greater results, interrelating with greater autonomy and the ability to self-regulate (Prieto, 2007). Empirically, there is a proven association with improved academic results and lower dropout rates (Caprara et al., 2008). Other authors agree that it is a strong predictor of students’ academic goals throughout adolescence as these adolescents value their grades and achievements if the outcome is higher than they had originally expected (Luszczynska, Gutiérrez-Doña & Schwarzer, 2005).

In relation to academic self-efficacy, McKay, Sumnall, Cole & Percy (2012) find that this, in conjunction with social and emotional self-efficacy, is also related to other health-related behaviors such as the overconsumption of alcohol. Similarly, Shell, Newman & Xiaoyi (2010) have found a direct relationship between the consumption of alcohol in adolescents, their expectations of themselves concerning alcohol consumption and self-efficacy. Accordingly, Zhao, Lu, Huang & Wang (2010) prove that self-efficacy regarding the use and increased use of the Internet is related to improved academic performance.

As previously mentioned, the educational environment is a setting in which positive development of students can easily be refected. Nonetheless, not all educational systems are alike nor do they try to meet the needs of adolescents in the same ways. Regarding the Spanish context in this manner, numerous changes have been observed for some years now, which have primarily affected Secondary Education. Among these, is the attempt to diversify the situation for those students opting for preparatory studies to gain admittance to a University and those seeking Vocational Training. Within this field of Vocational Training are also two distinctive student profiles: those who have successfully completed the required Secondary Education and wish to complete vocational training and those who have been admitted into Vocational Training through Initial Vocational Qualification Programs (PCPI) without having first successfully completed secondary education. This particular academic career is also associated with a distinctive personal profile (Merino, Garcia & Casal, 2006). This includes elements such as the interpretation of academic failure as a personal issue, an apparent disaffection towards different educational institutions, having uncertain expectations about the future and expressing a great lack of motivation.

Using this approach, this study attempts to analyze the relationships that exist among four psychological constructs within the framework of positive psychology and to determine whether or not students who have followed diverse academic careers display different scores in these areas. We expect to find relationships between the two careers, as has previously been discovered in other studies, yet with the possibility of determining diverse elements as much in the context of relationships, as in their relationship to the academic careers of participants.

MethodParticipantsA total of 332 adolescents from the city of Zaragoza (Spain) participated in this study. They represent three academic profiles that we can define after completion of the required Secondary Education. These include: adolescents who continue their education in high school with a focus on higher education (124), adolescents who begin their studies in Vocational Training after having successfully completed the required Secondary Education (125) and adolescents (83) who have been admitted into Qualification Programs for Vocational Training (PCPI) without having successfully completed the required Secondary Education.

If we analyze the data according to gender, 34.3% are female and 65.7% are male, with a higher percentage of females in the first group when compared to the rest of the group overall, 46.8% vs. 27.2% and 26.5% (χ2 = 13.589, p <.001). According to age, we find an average age of 16.92 ranging from 15 to 25 years old. The Vocational Training group displays a higher average for age [m=17.85 (s.d.=1.19) vs. m=16.28 (s.d=0.53) and m=16.49 (s.d.=0.77)], as it plays a greater variability in this characteristic (Welch = 89,891, p <.001; Levene = 14.119, p <.001).

Variables and instrumentsThe Spanish version (Ferrando, Chico & Tous, 2002) of the Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) of Scheier, Carver, and Bridges (1994) was used to evaluate dispositional optimism. It consists of ten items based on five-point Likert scale, in which three items measure optimism; three measure pessimism and four, which are complementary. A total score is obtained upon inverting the pessimism items. The Spanish version of the LOT-R has very similar psychometric properties to those of the original version, and the result in this investigation determined Cronbach’s alpha to be 0.75 for the entire questionnaire, 0.58 for items referring to pessimism and 0.54 for items regarding optimism.

The Spanish translation of the Adult Trait Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1991) was used to measure hope. This scale consists of twelve items based on an eight-point Likert scale. Initially, it was translated and reviewed by experts for the version of the Spanish adaptation. The result proved that the instrument, as a whole, is reliable (a = 0.87) as are its elements with a Cronbach alpha of 0.71 for the agency and 0.61 for pathways.

The Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC13) of Antonovsky (1987) was used to measure the sense of coherence. The questionnaire consisted of thirteen itemized responses based on a seven-point Likert scale. This questionnaire gathered four items of significance, five items based on comprehension and four based on manageability. According to Ericsson & Lindström (2007) Cronbach’s alpha is 0.86 for the total obtained score and in this study Cronbach’s alpha is 0.75, indicating the instrument’s reliability despite the discrepancy that was found. Furthermore, the calculation was performed for units of understanding, manageability and significance, finding results of 0.51, 0.27 and 0.41 respectively.

Conclusively, we apply an instrument of general self-efficacy according to the Spanish version of the Scale of General Self-Efficacy Scale (Sanjuan, Perez & Bermudez, 2000). It is comprised of ten items based on a ten-point Likert scale and measures the personal beliefs people have regarding their ability to manage daily stressors. According to Sanjuan et al. (2000), the instrument has a considerable internal consistency (α = 0.87), data that has been confirmed in this study (α = .86).

ProcedureThe study was conducted in the 2010/2011 and 2011/2012 academic years in Secondary and Vocational Training Schools in the city of Zaragoza. It is the fifth largest city in Spain and has a population of around 750,000 residents, in which data was collected from all groups. In order to attain the sample, all educational centers that had three educational levels were contacted and asked to collaborate with the research project. For those centers that agreed, meetings were arranged with the administrative team or guidance office in order to explain the objectives and outline the method of approach that would be used with students. During the first meeting, parental or guardian permission forms were handed out to students under the legal age of 18 in addition to a signed letter from the University of Zaragoza explaining the purpose and method of the research project. The anonymity of the participants was guaranteed at all times. Among the families and students who were contacted, neither group refused to participate, discounting from the research only those students who were absent on the days in which data was collected. The questionnaires were implemented and carried out by one of the researchers during regular hours of the school day, previously having made an appointment with the collaborating teacher in each district to do so.

Statistical procedureIn order to analyze the results of this research, a comparison of averages was conducted using parametric tests (analysis of variance) previously confirming the realization of presumed techniques, thoroughly testing for any possible invalidity of such procedures and if found, we used robust statistics. Once completed, and to then compare differences among students in the Vocational Training Programs with other students, a logistical regression analysis was monitored, testing for the capability of psychological variables to differentiate between these groups. Lastly, we made specific correlations among psychological variables and then groupings of such were analyzed using exploratory factor analysis (principal components, varimax rotation) and confirmatory factor analysis. The statistical program, SPSS 19.0, was used to for all calculations apart from the confirmatory model, in which AMOS 17.0 was used. This was based on the method of maximum credibility estimation, substituting lost values for the average so that we could obtain the modification index.

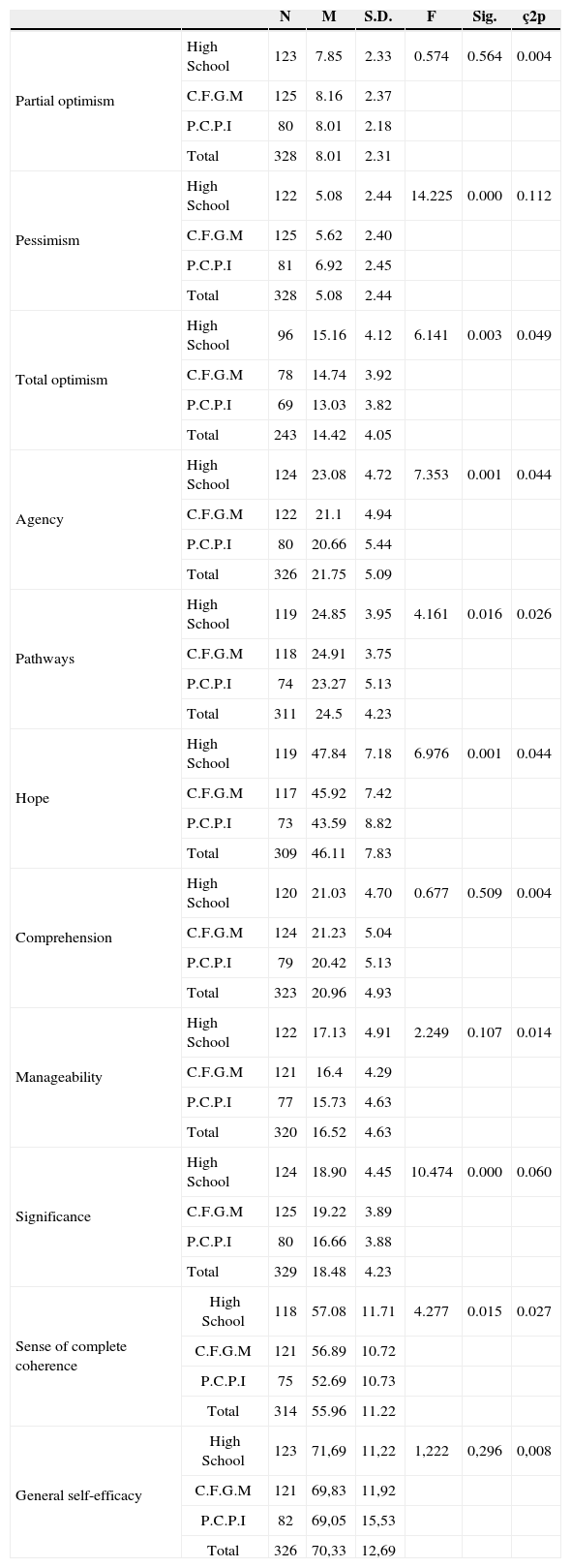

ResultsTable 1 shows the averages of the three groups of the variables of interest for this investigation. The results reveal that certain differences between the three groups of students exist, whereas other variables related to age or sex were not founded. Specifically, distinctive averages appear among the groups with reported levels of: a complete sense of coherence, a subscale of significance, a scale of complete optimism, a subscale of pessimism, and the total score of hope as in its subscales (Table 1).

Comparison of averages

| N | M | S.D. | F | Sig. | ç2p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial optimism | High School | 123 | 7.85 | 2.33 | 0.574 | 0.564 | 0.004 |

| C.F.G.M | 125 | 8.16 | 2.37 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 80 | 8.01 | 2.18 | ||||

| Total | 328 | 8.01 | 2.31 | ||||

| Pessimism | High School | 122 | 5.08 | 2.44 | 14.225 | 0.000 | 0.112 |

| C.F.G.M | 125 | 5.62 | 2.40 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 81 | 6.92 | 2.45 | ||||

| Total | 328 | 5.08 | 2.44 | ||||

| Total optimism | High School | 96 | 15.16 | 4.12 | 6.141 | 0.003 | 0.049 |

| C.F.G.M | 78 | 14.74 | 3.92 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 69 | 13.03 | 3.82 | ||||

| Total | 243 | 14.42 | 4.05 | ||||

| Agency | High School | 124 | 23.08 | 4.72 | 7.353 | 0.001 | 0.044 |

| C.F.G.M | 122 | 21.1 | 4.94 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 80 | 20.66 | 5.44 | ||||

| Total | 326 | 21.75 | 5.09 | ||||

| Pathways | High School | 119 | 24.85 | 3.95 | 4.161 | 0.016 | 0.026 |

| C.F.G.M | 118 | 24.91 | 3.75 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 74 | 23.27 | 5.13 | ||||

| Total | 311 | 24.5 | 4.23 | ||||

| Hope | High School | 119 | 47.84 | 7.18 | 6.976 | 0.001 | 0.044 |

| C.F.G.M | 117 | 45.92 | 7.42 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 73 | 43.59 | 8.82 | ||||

| Total | 309 | 46.11 | 7.83 | ||||

| Comprehension | High School | 120 | 21.03 | 4.70 | 0.677 | 0.509 | 0.004 |

| C.F.G.M | 124 | 21.23 | 5.04 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 79 | 20.42 | 5.13 | ||||

| Total | 323 | 20.96 | 4.93 | ||||

| Manageability | High School | 122 | 17.13 | 4.91 | 2.249 | 0.107 | 0.014 |

| C.F.G.M | 121 | 16.4 | 4.29 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 77 | 15.73 | 4.63 | ||||

| Total | 320 | 16.52 | 4.63 | ||||

| Significance | High School | 124 | 18.90 | 4.45 | 10.474 | 0.000 | 0.060 |

| C.F.G.M | 125 | 19.22 | 3.89 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 80 | 16.66 | 3.88 | ||||

| Total | 329 | 18.48 | 4.23 | ||||

| Sense of complete coherence | High School | 118 | 57.08 | 11.71 | 4.277 | 0.015 | 0.027 |

| C.F.G.M | 121 | 56.89 | 10.72 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 75 | 52.69 | 10.73 | ||||

| Total | 314 | 55.96 | 11.22 | ||||

| General self-efficacy | High School | 123 | 71,69 | 11,22 | 1,222 | 0,296 | 0,008 |

| C.F.G.M | 121 | 69,83 | 11,92 | ||||

| P.C.P.I | 82 | 69,05 | 15,53 | ||||

| Total | 326 | 70,33 | 12,69 |

No differences were found in general self-efficacy, in the subscales of comprehension, neither in the direction of a sense of coherence nor in that of partial optimism. Comparisons between groups show that students of the Initial Vocational Qualification Programs (PCPI) subgroup present different scores than those of the other two groups in each case. However, in the case of High School and Vocational Programs, differences were determined merely in the agency sub-scale of the hope scale. In those instances where the differences are statistically significant (Table 1), it is also demonstrated to be relevant due to the explained percentages of high variances, with partial eta squared values between 0.027 and 0.112.

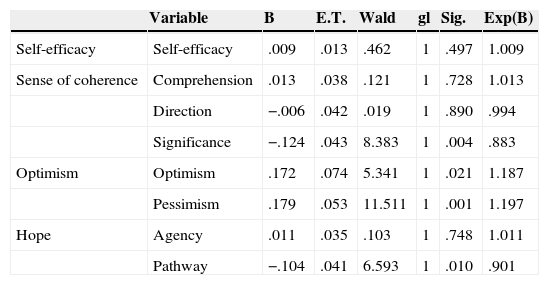

With these data, we proceeded to conduct a logistic regression analysis, grouping together all the participants belonging to the PCPI programs, and in another group, those students pertaining to High School and Vocational Programs. Sub-scales of the considered variables were used as predictors. The resulting model succeeds at accurately classifying 79.7% of cases, correctly identifying 97.3% of students in Vocational Training/High School and 21.2% of student in the PCPI program.

Table 2 shows weights of the distinctive variables in the regression equation. As can be seen, only four variables satisfy a significant contribution to the classification: the subscales of optimism and those of pessimism, the significant variable regarding a sense of coherence and the pathways regarding the scale of hope.

Summary points for logistic regression (PCPI vs High School and Vocational courses)

| Variable | B | E.T. | Wald | gl | Sig. | Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | Self-efficacy | .009 | .013 | .462 | 1 | .497 | 1.009 |

| Sense of coherence | Comprehension | .013 | .038 | .121 | 1 | .728 | 1.013 |

| Direction | −.006 | .042 | .019 | 1 | .890 | .994 | |

| Significance | −.124 | .043 | 8.383 | 1 | .004 | .883 | |

| Optimism | Optimism | .172 | .074 | 5.341 | 1 | .021 | 1.187 |

| Pessimism | .179 | .053 | 11.511 | 1 | .001 | 1.197 | |

| Hope | Agency | .011 | .035 | .103 | 1 | .748 | 1.011 |

| Pathway | −.104 | .041 | 6.593 | 1 | .010 | .901 |

With respect to the relationships among the different variables in this research, it is noteworthy that all correlations are statistically significant; with those that are part of the same construct maintaining the largest quantity. Subsequently, the overall scores of the scales display the greatest correlations, particularly, between hope and optimism (r = .503), optimism and sense of coherence (r = .541) and also between a sense of coherence and hope (r =. 456). Self-efficacy shows correlations r = .471 with hope, optimism r = .400 and r = .313 with a sense of coherence. The highest correlations between the sub-scales highlight that of hope, which in the case of route components correlates with general self-efficacy (r = .477), partial optimism (r =. 368) and pessimism (r = -342). Meanwhile, the agency subcomponent is correlated with the direction and significance of a sense of coherence (r = .301 and r = .496), self-efficacy (r = .333), optimism and pessimism (r = 343 and r = - 440).

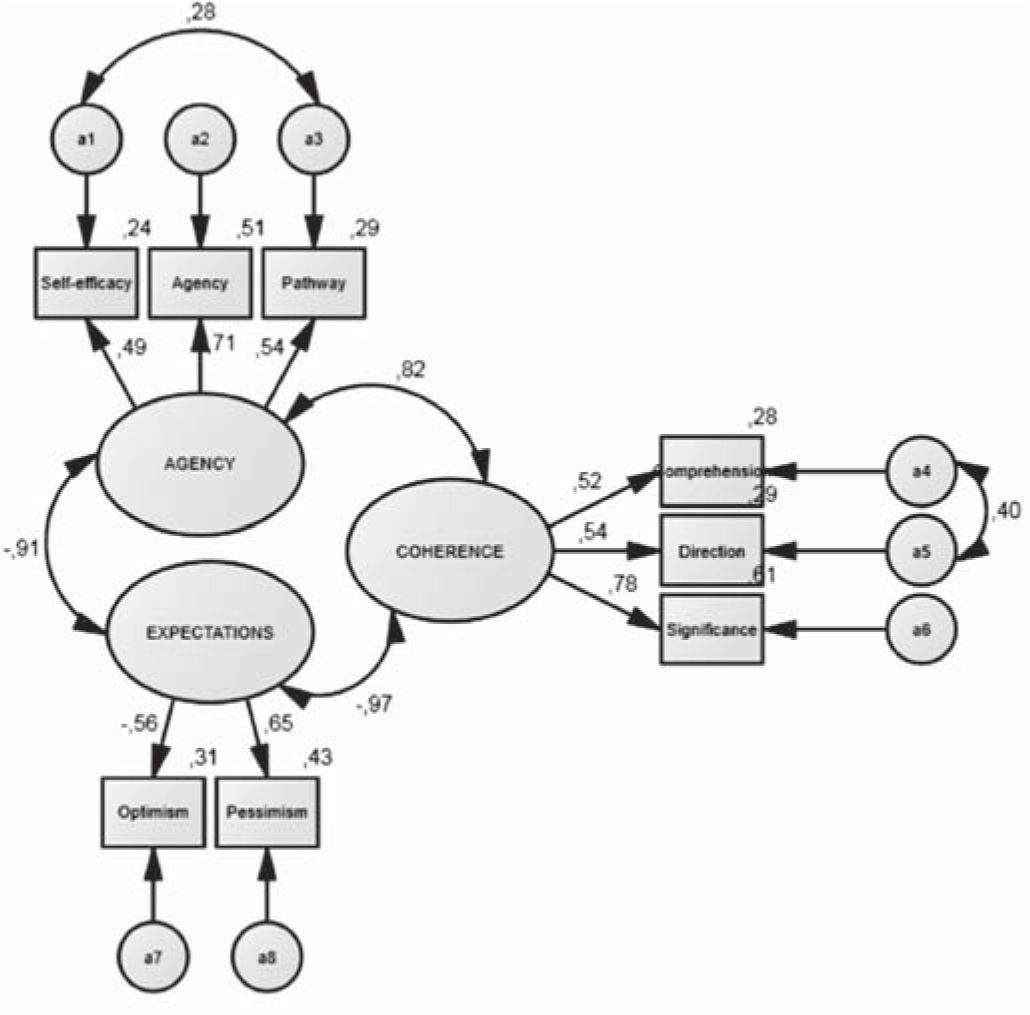

In a post-analysis, we proceeded to carry out an exploratory factorial analysis of the different sub-scales that were used in this research, using the method of principal components, analysis and varimax rotation. It resulted in a structure with two factors explaining 61.157% of the variance. Of all the variables, subscales of optimism display less commonality: .388 and .478. In continuation, the factors were grouped based on the sub-scales of the sense of coherence while separately; all other factors were grouped together.

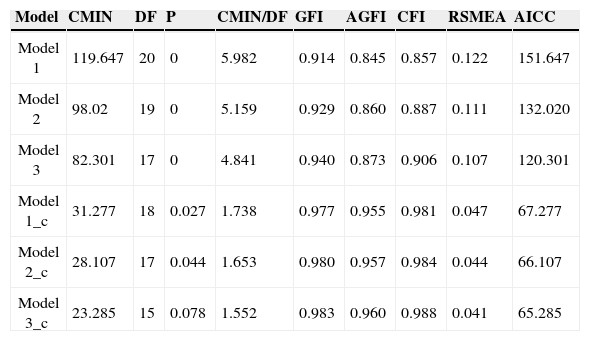

Lastly, we attempted to test different factorial structures using confirmatory factor analysis based on the scoring for the different sub-scales. Adjustment was tested in three different models. The first model includes all the scales grouped together (model 1). The second model includes differentiation between two correlated factors, the components of a sense of coherence from one standpoint and the remaining variables from another (model 2). The third model comprises three factors: one based on the scales of a sense of coherence, another regarding optimism and a third factor including self-efficacy and hope (model 3).

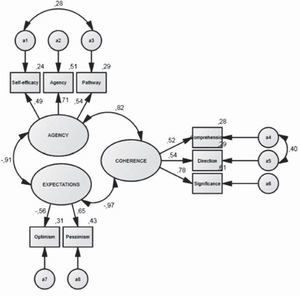

The results for the models of adjustments show low results in all cases (Table 3). However, each case produces greater results by introducing a covariance between the errors. In all three cases, we determine alternative models showing high levels of adjustment upon incorporating a covariance between the estimation errors for the sub-scales of direction, comprehension of the sense of coherence, self-efficacy and the subscale of pathways (Table 3). The final adjustment in all three cases is exceptional, shown to be slightly superior in the case of model 3. Figure 1 shows the standardized results of this latest model.

Adjustment Indicators for structural equation models

| Model | CMIN | DF | P | CMIN/DF | GFI | AGFI | CFI | RSMEA | AICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 119.647 | 20 | 0 | 5.982 | 0.914 | 0.845 | 0.857 | 0.122 | 151.647 |

| Model 2 | 98.02 | 19 | 0 | 5.159 | 0.929 | 0.860 | 0.887 | 0.111 | 132.020 |

| Model 3 | 82.301 | 17 | 0 | 4.841 | 0.940 | 0.873 | 0.906 | 0.107 | 120.301 |

| Model 1_c | 31.277 | 18 | 0.027 | 1.738 | 0.977 | 0.955 | 0.981 | 0.047 | 67.277 |

| Model 2_c | 28.107 | 17 | 0.044 | 1.653 | 0.980 | 0.957 | 0.984 | 0.044 | 66.107 |

| Model 3_c | 23.285 | 15 | 0.078 | 1.552 | 0.983 | 0.960 | 0.988 | 0.041 | 65.285 |

In recent years, the expansion of positive psychology has generated a great deal of research and advances in scientific knowledge of the human mind. However, as in any process of scientific advancement, a critical perspective is key in improving both the theories that uphold such progress as well as the supporting data. Both elements are necessary to ensure various developments and due to the generated popularity of various new approaches, it is necessary to avoid discourses and applications that may be developed because of greater economic or ideological interest rather than for scientific gain (Orejudo and Teruel, 2009).

From this perspective, this research proposes the possibility of using classical constructs in scientific psychology that have been collected within the field of positive psychology, so to analyze the positive development in adolescents. The attention towards adolescent development focuses on identifying the conditions that promote the development of competencies and adaptive skills in the various areas of personal, cognitive, social or moral behavior (Oliva et al., 2010). Our interest in creating this approach is based on the need to help shape a broad theory regarding behavior and to further understand the conditions that account for such development, by providing elements to intervene and improve the personal lives of adolescent students.

To accomplish this, we collected some constructs that, with certain tradition, are part of fields of applied positive psychology in the development of adolescents (Gilman et al., 2009), whereas this is a more recent contribution in other cases, such as the sense of coherence. The results support the idea that, as a whole, the evaluated constructs in this investigation outline a unique psychological profile, having elements of positive development in common, as refected in the posed structural equation models. Even if this is so, particular elements can also be differentiated; from related biases with the instruments of measurement to characteristics and composition of the sample and from subtle theoretical differences between distinct constructs; the last proposal being the most plausible theoretical result, as discussed below.

Thus, several of these constructs are incorporated into models of self-regulation of behavior or have components that indicate the importance of having goals as a motivational factor (Carver & Scheier, 2002, Snyder et al., 2005). These goals are proven to be hierarchical and vary from one context to another, whereby the combination with the demands of the different areas in which they assume different roles can explain much of adolescent behavior. This set of goals and demands could constitute an established system for explaining behavior, along with the adaptation of interrelationships with constructs that have been previously indicated and allow for an exclusive pathway to improve adolescent development (Anderman & Anderman, 2009; Lopez, Rose, Robinson, Marques, Pais-Ribeiro, 2009).

In the same way, a combined system of general expectations that influence goals is established, where emotions and resources are put into place. In our case this would constitute self-efficacy as much as expectations of future optimists and pessimists. Additional elements would be added to these systems: the coping of life events, for which the elements of a sense of coherence could make a preliminary projection, in connection to other means of coping. Similarly, adding specific resources to achieve goals and meet the demands of one’s environment must be addressed in the areas of social competencies, emotional or self-regulatory. In our research, this role is both general self-efficacy as it is hope.

After this first tentative approach towards a model of positive adolescent development, we add further refections about the elements that can be advantageous to this development, equally guided by the four constructs we investigated. As previously noted, we have found that adolescents who continue to experience unsuccessful academic careers show a distinctive personal development that, qualitatively, would be less favorable than the remaining adolescents. These data have implications for professionals working with adolescents, requiring that we offer resources to improve theses competencies. On the other hand, they reveal certain important theoretical implications.

Therefore, as previously discussed in the introduction to this paper, there are many data that support the relationship between academic context variables and development, among others, academic achievement, the perception of it, school stress levels or attachment to school. However, we cannot assume that academic failure on its own is responsible for this difference in personal pathways, though it could be a crucial factor pertaining to it, especially considering that the relationships between context and development are complex. So, it should be noted that learning these skills in the adolescent stage influences both macro and microsystems. In the first case, there is evidence to support the importance of cultural and socioeconomic variables in the configuration thereafter, keeping in mind that we cannot speak of unidirectional relationships, as development is a constant interaction between context and the person. Thus, despite finding a relationship between educational success and psychological variables in our research, we cannot determine that success or failure be the determinants of optimism, hope, self-efficacy or a sense of coherence, as compared to the same educational context of adolescents with previous differences in these levels who may have qualitatively diverse behaviors.

In this way, there is a clear relationship between success and optimism (Smith and Hoy, 2007), whereas hope can also predict longitudinal academic achievement in standard contexts (Snyder et al., 2002) as in ethnic minorities or low-income groups (Adelabu, 2008). It is also possible that adolescents with better personal competencies, such as hope, may be affected by the behavior of their environment, including teacher expectations and support, establishing and achieving educational goals and fostering autonomy (Tinsley & Spencer, 2010; Van Ryzin, 2011). Several works support this adaptive capability of hope, optimism or self-esteem (Guse & Vermaak, 2011; Yarcheski, Mahon & Yarcheski, 2011). Regarding a sense of coherence, Edbom, Malmberg, Lichtenstein, Granlund & Larsson (2010) affirm that adolescents with Attention Deficit Disorder have a longer period of symptoms and much less coherence that in people with high levels of coherence. On the extreme opposite side of the spectrum, Pennanen, Haukkala, De Vries & Vartiainen (2011) test for how one can maintain a negative dynamic. These include students who have lower performance scores that evolve towards more favorable attitudes toward drugs, lower self-efficacy and refuse offers of consumption and greater intention to smoke.

It is noteworthy to recognize that the school context parallels the family microsystem, also having an influence on positive development among adolescents. Without having extended our research in this field, the work of Dumka, Gonzales, Wheeler & Millsap (2010) offer an example of this connection based on their findings. In the case of self-efficacy, they found that the educational practices of parents who have greater levels of self-efficacy encourage their children to experience feelings of freedom and offer more frequent opportunities of choosing activities outside the family environment; allowing adolescents to generate significant personal short and long-term goals and to acquire greater social competencies. Moreover, parents’ self-efficacy may be beneficial to teens as these parents are involved in more positive educational practices with their children, which positively impacts adolescent behavior.

In practice, the importance of considering an educational environment as a context in promoting positive development in adolescents is apparent (Van Ryzin, 2011). Additionally, this affects progression of personal characteristics through interaction, which is established with different elements of the education sub-system such as educators, academic careers and academic resumes, among others. For an ordinary resume, extracurricular activities and non-formal education could enhance one’s background, demonstrating work potential for adolescents with the explained profiles (Kirschman, Roberts, Shadlow & Pelley, 2010). In addition to these possibilities is the development of specific programs for the advancement of these abilities, as in our context was found to be necessary for students who have not had experienced academic success in their high school careers (Pertegal, Oliva & Hernando, 2010). Addressing ways for intervention extends beyond the scope of this research, however, it is an area that we should not disregard, as we understand that personal skills are essential to general positive development in adolescents (Roth and Brooks-Gunn, 2003), moreover in teens who lack these skills and for those whom this condition could display a risk of social exclusion (Repetto, Pena, Mudarra & Uribarri, 2007).

In conclusion, we cannot complete our research without pointing out certain limitations. First and foremost is that the results do not extend to other contexts, as previously mentioned that this research was conducted in a culturally specific area of Spain. Therefore, it is possible that the significance of academic failure would not be the same in areas where admittance to an education system is universal and mandatory as it would be for those who, in part, are accepted based on other means such as geographic or economic situations. Moreover, this study was conducted with adolescents, a stage in which personal identity is shaped and more clearly developed. The interrelationships found with certain aspects of teens could differ when dealing with adults or more homogenous groups, which could result in the instruments of measurement as not being reliable for those studies. Lastly, even when the sampling is not random, it does try to represent a large number of adolescents, though we may find an under-represented female sample in the adolescent group of Initial Programs of Vocational Qualification (PCPI). Considering these aspects, we emphasize the need for longitudinal studies, which underline the evolutionary process and maintain the diversity of variables. In this way we can better understand adolescent behavior and the various implications, which are not solely academic and professional, yet also personal and socio-emotional.

Author’s contribution to this paper was as follows: SOH was responsible of the theoretical framework, of the research planning and data processing, LAM was responsible of planning data collection, selection of instruments and their adaptation to Castilian; JCE was responsible of the theoretical framework in educational part. The three authors review and approved the final version submitted for publication. All correspondence should be directed to: Santos Orejudo Hernández, PhD. Facultad de Educación. Universidad de Zaragoza, C/ San Juan Bosco, 7 (50009 Zaragoza). España.