MCDM methods are useful to obtain information and generate knowledge useful for decision-making processes in multidisciplinary contexts. Particularly, when conflicts occur, knowledge is the key to start negotiation processes between stakeholders in order to achieve consensual solutions. The planning of protected areas is complex due to many competing uses of natural resources and the involvement of a large number of stakeholders. For the last ten years, participative MCDM methodologies have been carried out efficiently to reduce conflicts and allow to formalize stakeholder's participation in the policy development processes. In this paper, we propose a MCDM participative methodology in three levels that seeks to define management plans in protected areas. This method allows for the definition of management plans based on three levels of criteria that define the use of the natural area and provide a ranking of the main goals according to the stakeholders’ priorities. The model was tested in two Spanish protected areas: Parque Natural de Lago de Sanabria y alrededores and Parque Natural de los Arribes del Duero. Firstly, the individual preferences of the most representative stakeholder groups were collected (Farmers, Business owners, Government and Scientists) and analyzed using two multi-criteria methods: AHP and GP. Moreover, a conflict index between stakeholders’ groups was calculated. Results showed that conservation and development goals are the most preferred to consider for the planning of these areas. Furthermore, the most serious disagreement was found between farmers and scientists and between farmers and government about the wildlife conservation.

Around the world, conservation is increasingly in conflict with other human activities (Martín, Rodriguez, Mejía, & Salinas, 2018; Redpath et al., 2013; Rodríguez, Aguilera, Martín, & Salinas, 2018; Rodríguez, Martín, & Aguilera, 2018). For this reason, protected areas are complex scenarios where the decision-making processes can be hard and achieving conservation goals can be hindered because of major disagreements between the objectives of stakeholder groups. Many times, these conflicts become stronger when the knowledge about the stakeholders’ interests are unknown or when the knowledge transfer is not efficient between decision-making levels of governance. In this context, conflicts related to land use are the greatest ones (de Castro & Urios, 2016) and it can jeopardize the achievement of the conservation objectives in protected areas (Shahabuddin & Rao, 2010). Fortunately, effective conflict management and long-term conservation benefits can be enhanced by better integration of the underpinning social context with the problems and evaluation of the efficacy of conflict management (Redpath et al., 2013). In this line, conservation management in protected areas requires special attention regarding three topics: collaboration, coordination between different levels of governance and resilience. To ensure these elements is necessary to define correct management plans in the early stages considering a conjoint approach to the goals.

The Protected Areas framework is based on underlying management principles agreed among stakeholders, i.e. common values and vision, local people participation, commitment of decision-makers and park staff collaboration. For this reason, is particularly important to consider the appropriate integration of all the stakeholders throughout the planning process to guarantee the consensus between all the stakeholder groups and between all the governments involved.

Multi-Criteria Decision Making methods (MCDM) have been very useful to identify and integrate the preferences of many participants involved in a decision-making process (Garrido-Baserba et al., 2016). On the one hand, these methods allow people to obtain knowledge that is useful for managers to make decisions (Depeige & Girodon, 2015; Marafon, Ensslin, Lacerda, & Ensslin, 2015). On the other hand, this analysis can be applied to the assessment of the innovation (Alfaro-Garcia, Gil-Lafuente, & Alfaro Calderon, 2017; Hesamamiri, Mahdavi Mazdeh, & Bourouni, 2016). Both utilities allow for the improvement of the planning and management of multi-disciplinary and complex scenarios that involve many stakeholders in decision-making processes. The application of MCDM methods through participative processes for the management in protected areas has increased in the last decade (de Castro & Urios, 2016) and their effectivity has been demonstrated in some complex cases, as the implementation of Red Natura 2000 (Blondet et al., 2017). In the context of natural reserves, the importance to ensure participation of all stakeholders is particularly important because it increases the complexity of the decision-making processes, from both a methodological and a social perspective.

Despite the convenience of involving local communities in the decision-making for the planning of transboundary reserves, the aggregation of individual preferences is a complex process that usually presents consistency problems related to groupal consensus and social legitimacy problems, related to the ethical validity of conjoint result. The problem of the social choice theory is behind the diversity of individual preferences and concerns in one society and refers to how to relate global evaluations and decisions with the individual interests (Sen, 2001). This problem requires to be careful with the aggregation process selected in order to maximize the consensus. In this sense, multi-criteria analyses can facilitate and add rigor to the stakeholder participation in the policy development process (Adem Esmail & Geneletti, 2018; Cegan, Filion, Keisler, & Linkov, 2017), provide a structured framework for negotiation and solve conflicts. Furthermore, the knowledge transfer can be efficient using sequential methods as inter-clustering analysis (Franco & Esteves, 2018).

In this work, we propose a methodology based on a hierarchical MCDM method, that allows us to generate knowledge about the stakeholders’ preferences in a protected area and to ensure the knowledge transfer between decisional levels. Also, the method allows us to identify discrepancies between stakeholders’ groups related to the priorities of the management team. In this paper we present a case study of two Spanish natural parks: Parque Natural Arribes del Duero and Parque Natural Lago de Sanabria. Both parks constitute the Spanish part of the Transboundary Protected Area named Meseta Ibérica, a Transboundary Biosphere Reserve formed by two Spanish natural parks and two Portuguese natural parks. In the second section the methods are described, in the third section a case study is described, in the fourth section the results of the case study and discussion are presented and finally, in the fifth section encompasses the conclusions.

MethodsThe proposed model lays in two multicriteria techniques: the Analytical Hierarchy Process and Goal Programming. The Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) allows to collect subjective assessments and to quantify the trade offs between pairwise comparisons (Saaty, 1980), considering individual preferences through opinions about the relative importance about the criteria and the alternatives using pairwise comparisons (Saaty, 1980). AHP is one of the most used multicriteria methods to solve decision problems about natural resources with the involvement of stakeholders (Cegan et al., 2017). Despite its versatility, this method presents some limitations related with two problems: a high number of inconsistent primary responses and the possibility of the reversibility of the ranking, with the associated problem of the weakness of the results when it changes the number of the criteria considered (Ho & Ma, 2017; Pérez-Rodríguez & Rojo-Alboreca, 2017). Pairwise comparison matrices must be reciprocal, homogeneous, and consistent (Saaty, 2006). The level of consistency can be measured with the Consistency Index, the cumulative average of matrix inconsistencies. The Consistency Ratio (CR) is the comparison between the Consistency Index and the Random Consistency Index. An acceptable Consistency Ratio is equal or less to 0.10 (Saaty, 2006). However, in pairwise comparisons, frequently primary results present a CR higher than 0.10, given the fact that the judgment may have innate subjectivity. Fortunately, González-Pachón and Romero (2004) developed a GP that uses a distance-based framework approach to inconsistencies in pairwise comparison matrices.

Goal Programming (GP) is a versatile multi-criteria technique used to resolve complex problems. GP finds compromise solutions that may not fully satisfy all the goals but do reach certain satisfaction levels set by the decision-maker. Particularly, weighted GP seeks to minimize the weighted sum of the deviations from each goal (Romero, 1991). The goal of the model proposed by González-Pachón and Romero (2004) is to deal with inconsistencies, to obtain a matrix that is as similar as possible to the one generated by the decision-maker while meeting Saaty's conditions of similarity, reciprocity, and consistency.

The proposed methodology involved three stages: (i) identification of relevant criteria for the transboundary reserve, (ii) the assessment of the criteria by stakeholders and individual results, and (iii) conflict analysis.

- (i)

Identification of relevant criteria for the transboundary reserve

In order to achieve the success of a transboundary reserve is necessary to define accurately the basis that will support the conjoint planning structure. This requires having into account all the key elements for all the countries and stakeholders’ groups involved in the area considered. Identifying the objectives that will be included in the management plans must be the result of an exhaustively review of all the management documents defined for each protected area and all the management document related with the governance of each municipality.

After that, a hierarchical rankscale will be built, that will represent, in a rigorous and organized manner, all the key topics. Therefore, all the objectives considered will be organized in multilayer and work scales.

- (ii)

Assessment of the criteria by stakeholders and individual results

The preferences of the participants are gathered by means of a Saaty survey. As the result of this assessment, we will obtain as many pairwise comparison matrices as participants in each group defined in the hierarchy defined in step (i).

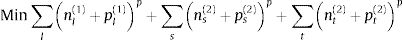

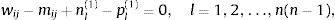

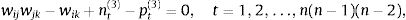

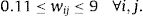

To correct the inconsistent matrices (CR <0.10), we will apply an Archimedean GP model as laid out by González-Pachón and Romero (2004) (Eqs. (1)–(5)).

s.t.Let M=(mij)ij a general matrix given by a participant, there exists a set of positive numbers, (wl…wn), such that mij=wiwj for every i,j=1,…,n.

After correcting the inconsistencies, the total of the consistent matrices is aggregated using a geometric average and the final weights are calculated using the eigenvalue method. Thus, as the result of assessment 2, we will obtain the weights that represent the conjoint relative relevance for each criterion analyzed.

- (iii)

Conflict analysis

These analyses make possible to identify divergences between specific weights of each criterion in each level of the hierarchy. Moreover, it will be possible to quantify the conflicts between groups using a Conflict Index (CI).

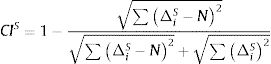

The Conflict Index of each group versus the conjoint result (CIS) is calculated using Eq. (6), based on Pang and Liang (2012).

where ΔlS represents the absolute difference between αiS and αi, thus, ΔiS=αiS−αi andαiS is the value of the preference of each stakeholders’ group S for each pair

αi is the value of the conjoint preference for each pair.

0≤Δik≤N, when value of N are S=sα|α=0,1,…,l so N=l, and N represents the maximum disagreement possible.

The value of the Conflict Index always will be 0≤CIS≤1, when CIS=0, individual assessment will be the same that the aggregated assessment, and when CIS=1, individual assessments will be as far away as possible from the aggregated assessment. Similarly, CI allows us to assess discrepancies between individual results and conjoint result, and between groups of the countries involved in the management of the transboundary reserve.

Case studyThe model has been tested in two natural parks in Spain: Parque Natural de Lago de Sanabria (Zamora) and Parque Natural de los Arribes del Duero (Salamanca and Zamora). Both parks constitute the Spanish area of the Transboundary Biosphere Reserve Meseta ibérica.

The area of study is representative of the mountainous landscapes in the northwestern Iberian Peninsula. The main economic activities have been historically related to agriculture, although many lands have been abandoned and progressively covered by forest (Azevedo, Moreira, Castro, & Loureiro, 2011). Rural exodus of the last century, differences in land management and fire suppression, policies between the two countries and the different protection schemes could define these landscapes (Regos, Ninyerola, Moré, & Pons, 2015). This progressive abandonment of the lands and the high risk of fire related to this (Fernandes, Loureiro, Magalhães, Ferreira, & Fernandes, 2012) requires defining careful management plans, incorporating relevant objectives for nature conservation, but furthermore aligned with stakeholders’ preferences.

In order to obtain the stakeholders’ preference, the individual preferences of the most representative stakeholder groups were collected (Farmers, Business owners, Government and Scientists). Governmental group are formed by representants and technicians of the local governments. The members of this group have the capacity to make decisions related to the management of the reserve. The farmer group comprises associations and key actors that represent the interests of the owner of lands, agriculture and cattle men/women, into the reserve. Enterprise groups are formed by owners of little business located within the territory of the reserve. Most of the business are hostels, restaurants, little commerce and other activities related to tourism. Finally, the scientist group is formed by experts with high knowledge about the reserve, but they do not live in this area.

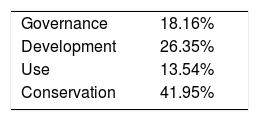

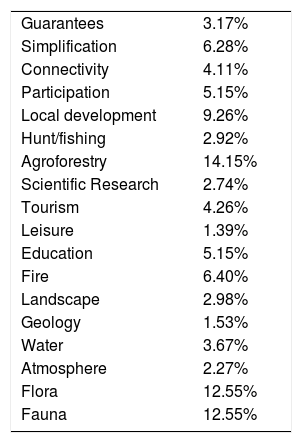

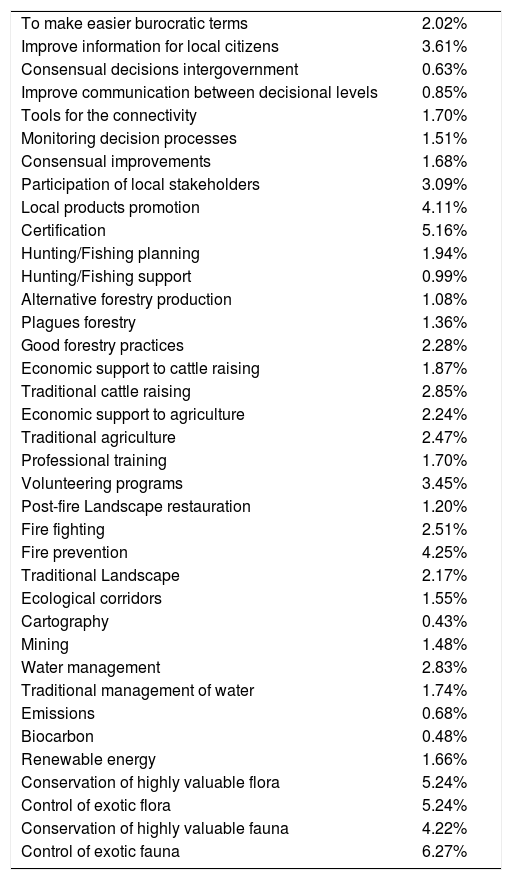

The knowledge about the preferences of these stakeholders was collected following a hierarchical structure based on three levels. The first level involves four dimensions (Conservation, Use, Development, and Governance). The second level involves 18 criteria (Fauna, Flora, Atmosphere, Water, Geology, Landscape, Fire, Education, Leisure, Tourism, Scientific Research, Agroforestry, Hunt/Fishing, Local development, Participation, Connectivity, Simplification, and Guarantees). The third level involves 36 sub-criteria (Control of exotic fauna, Conservation of highly valuable fauna, Control of exotic flora, Conservation of highly valuable flora, Renewable energy, Biocarbon, Emissions, Traditional management of water, Water management planning, Mining, Cartography, Ecological Corridors, Traditional Landscape, Fire prevention, Fire fighting, Post-fire Landscape restauration, Volunteering programs, Professional training, Traditional agriculture, Economic support to agriculture, Traditional cattle raising. Economic support to cattle raising, Good forestry practices, Forest pests, Alternative forestry products, Economic support to Hunting/Fishing, Hunting/Fishing planning, Certification, Local products promotion, Participation of local stakeholders, Consensual improvements, Monitoring decision processes, Tools for connectivity). Criteria and sub-criteria involve the most important topics to consider in the management plan.

To collect the stakeholders’ preferences, we carried out a survey based on the topics identified above. This is a survey of type Saaty that collected pairwise comparisons for the dimensions, criteria and sub-criteria.

Results and discussionThe survey used to collect the preferences of the stakeholders took place between July 2017 and June 2018 and was carried out online and through personal enterviews. Finally, we collected a sample of 40 surveys of the most representative stakeholders in Puebla de Sanabria Natural Park and Arribes del Duero Natural Park. The distribution into stakeholder groups was: 12 local governments representatives, 12 farmers, 12 business owners and 3 scientists. The results of the assessment and the conflict analysis are as follows.

40 surveys were analyzed using the AHP described in Methods section. As a result of the assessment, 1,176 matrices were obtained and the inconsistency of 254 matrices were corrected by using a Goal Programming model (Eq. (1)), recovering 234 consistent matrices. Finally, a total of 1156 valid matrices were analyzed.

Once corrected the inconsistencies, all the consistent matrices were aggregated using a Geometrical Average and the weights for each criterion were calculated by using the eigenvalue method. These weights represent the relative importance of each criterion assessed. Global weights are represented in Tables 1–3.

Global weights for level 2.

| Guarantees | 3.17% |

| Simplification | 6.28% |

| Connectivity | 4.11% |

| Participation | 5.15% |

| Local development | 9.26% |

| Hunt/fishing | 2.92% |

| Agroforestry | 14.15% |

| Scientific Research | 2.74% |

| Tourism | 4.26% |

| Leisure | 1.39% |

| Education | 5.15% |

| Fire | 6.40% |

| Landscape | 2.98% |

| Geology | 1.53% |

| Water | 3.67% |

| Atmosphere | 2.27% |

| Flora | 12.55% |

| Fauna | 12.55% |

Source: The authors.

Global weights for level 2.

| To make easier burocratic terms | 2.02% |

| Improve information for local citizens | 3.61% |

| Consensual decisions intergovernment | 0.63% |

| Improve communication between decisional levels | 0.85% |

| Tools for the connectivity | 1.70% |

| Monitoring decision processes | 1.51% |

| Consensual improvements | 1.68% |

| Participation of local stakeholders | 3.09% |

| Local products promotion | 4.11% |

| Certification | 5.16% |

| Hunting/Fishing planning | 1.94% |

| Hunting/Fishing support | 0.99% |

| Alternative forestry production | 1.08% |

| Plagues forestry | 1.36% |

| Good forestry practices | 2.28% |

| Economic support to cattle raising | 1.87% |

| Traditional cattle raising | 2.85% |

| Economic support to agriculture | 2.24% |

| Traditional agriculture | 2.47% |

| Professional training | 1.70% |

| Volunteering programs | 3.45% |

| Post-fire Landscape restauration | 1.20% |

| Fire fighting | 2.51% |

| Fire prevention | 4.25% |

| Traditional Landscape | 2.17% |

| Ecological corridors | 1.55% |

| Cartography | 0.43% |

| Mining | 1.48% |

| Water management | 2.83% |

| Traditional management of water | 1.74% |

| Emissions | 0.68% |

| Biocarbon | 0.48% |

| Renewable energy | 1.66% |

| Conservation of highly valuable flora | 5.24% |

| Control of exotic flora | 5.24% |

| Conservation of highly valuable fauna | 4.22% |

| Control of exotic fauna | 6.27% |

Source: The authors.

The first level shows that Conservation and Development topics are the most valued topics with 41.95% and 26.34%, respectively. In the second level, Agroforestry (14.15%) is the most important goal for the stakeholders, followed by Fauna (12.55%) and Flora (12.55%). Finally, the cluster Use obtained the worst assessments for Leisure (1.35%). The reason could be the potential impact in the environment and the low income.

The analysis of the third level shows that the topics related with the conservation of highly valuable species and the control of exotic species both fauna and flora were the most valued topics. Prevention of fire also obtained high values in the global analysis (4.25%). Also, the local development is relevant for the stakeholders, particularly, the certification of local products (5.16%) and promoting local products (4.11%). In the cluster Use and Governance, the top priorities were volunteering programs and the improvement of information for local citizens, respectively.

The high importance assigned to conservation is in line of the study of Sarkki, Heikkinen, Herva, and Saarinen (2018). They reinterpret some myths about land governance, like tragedy of the commons. This myth is based on arguments for and against herders’ short-term individual profit maximization at the expense of long term and common sustainability. However, Sarkki et al. (2018) show that a holistic approach is also needed to understand the various connections of reindeer herding to the existing market economy, and to promote new ways of engaging with it. Following this line, other authors have showed that the management of local communities can be efficient for a sustainable use of the land in a context of good governance (Shahabuddin & Rao, 2010).

During the field work, we verified that the most interested people in the conservation of the land are the people already living in it. Moreover, the development of the land would be imposible if resources finished. However, sometimes, the excessive number of rules and the complexity of the governance avoid the real land use by local communities, laying in sub-national, national or international governments and far away of the local interests. Moreover, the participative processes defined as a mere public consultation in some steps of the Transboundary Protected Area Protected development process, do not allow a true integration of the interests of local communities. In fact, 100% of local people interviewed describe themselves as non-decision-makers at their own land.

In this sense, results offer the second most important topic in Governance level, the participation of stakeholders (4.09%), second only after to the improvement of the information for local people. Local people prioritize their participation in the planning of the land use as decision-makers in detriment of the connectivity between governments or guarantees for the owners, thus, the contemporary participatory processes seem insufficient. As Trillo-Santamaria and Paül (2016) remark, “local people's opinions, values and feelings about the Transboundary Protected Area, have to be a constant reason for action”.

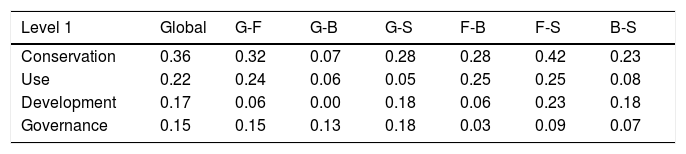

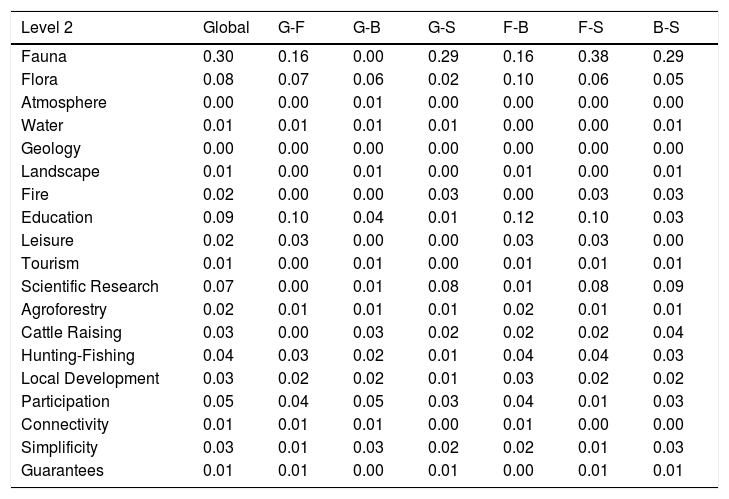

Tables 4 and 5 show the global and inter-group Conflict Index in Level 1 and 2. The higher conflicts occur in the conservation cluster in level 1 (0.36) and in the fauna conservation in level 2 (0.30). In first level, the strongest conflicts were found between farmers and scientists (0.42) and between local government and farmers (0.32).

Global and inter-group Conflict Index for Level 2.

| Level 2 | Global | G-F | G-B | G-S | F-B | F-S | B-S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fauna | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.29 |

| Flora | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Atmosphere | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Water | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Geology | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Landscape | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Fire | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Education | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| Leisure | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Tourism | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Scientific Research | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Agroforestry | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Cattle Raising | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Hunting-Fishing | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Local Development | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Participation | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Connectivity | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Simplificity | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Guarantees | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Source: The authors.

In level 2, the most conflictive valuations were found between farmers and scientists (0.38) and between government and scientists (0.29) and between business owners and scientists (0.29). We hope to find the strongest conflicts related to the wildlife conservation. Traditionally, humans respond by killing wildlife and transforming wild habitats to prevent further losses. This method could allow to quantify the conflict ensuring the sequentially knowledge transfer through levels. This information could be very useful to establish communication channels between stakeholders, start negotiation processes and define incentives for wildlife conservation between local people.

ConclusionsThe MCDM method used to collect the stakeholders’ preferences has been able to generate knowledge about the priorities of the stakeholders in the protected territory studied. This knowledge has been developed sequentially based on a hierarchical structure, in order to connect all the governance levels. Thus, we ensure the knowledge transfer through all decisional levels involved in protected areas.

Results showed that the most important goals for the stakeholders in the analyzed areas were related to the conservation and development in a first level. With agroforestry and conservation of fauna and local development in a second level, and with the conservation of highly valuable species of fauna and flora, control of exotic species, certification of local products and fire prevention, in the third level. Moreover, the highest divergences were related to the wildlife conservation and the most important conflicts were found between farmers and scientists and between farmers and government.

The case study allowed to test the utility of these methods to identify multi-level conflicts involved with decision-making processes in protected areas. This analysis could improve the governance of this type of protected areas, pinpointing conflicts between stakeholders’ groups. It could be interesting to apply and assess other participative methods in order to improve the planning of protected areas in contexts especially complex such as the transboundary context.