The pandemic caused by the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has affected 15,785,641 people in 188 countries and caused 640,016 deaths since the first cases were reported in Wuhan, China.1,2 Spain is one of the countries that has been most affected, with an incidence of 272,421 cases and 28,432 deaths as of 26 July 2020.1 The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, called COVID-19, manifests itself with clinical conditions of varying severity. It is estimated that approximately 80% of patients have a mild disease, 20% require hospitalisation and 5% require admission to critical care units.3 Patients who develop a severe infection usually do so in the form of hypoxemic respiratory failure.4 The main symptoms are fever, cough, dyspnea, asthenia and myalgias.5 A proportion of the patients do not develop symptoms but act as potential transmitters.6 Mortality is estimated at 4% of diagnosed cases.1

Healthcare due to COVID-19 has caused an unprecedented impact on the Spanish health system. The response to the pandemic has forced the mobilisation of health resources (hiring of final-year medical and nursing students, recruitment of recently retired doctors, equipping additional critical units, multiplying the diagnostic capacity of laboratories, etc.) and expedient resources (makeshift medical pavilions and hotels, etc.) to face the high demand for care of critically ill patients.7 All the healthcare areas, from Primary Care, social health, residential, Mental Health, Emergency departments, and hospital, have been quickly reorganised to transform spaces and equipment.

In the hospital setting, the healthcare teams have been organised into the so-called COVID units, composed of professionals from various specialities, clinically led by specialists in Internal Medicine, Infectious Diseases or Intensive Medicine. They have cared for patients with COVID-19 following protocols implanted for diagnosis, treatment and case management that have been adapted as soon as new and changing information became available.8 One of the many challenges faced by the COVID units has been the care of a large volume of patients (whether with advanced chronic diseases or previously healthy) who have abruptly entered a situation rapidly approaching end of life and have died.

Healthcare settings outside of the hospital (private and nursing homes) have had enormous difficulties: the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) has added to the difficulty in establishing the circuit of care for infected patients and the limited access for performing confirmatory tests of infection. Health care for patients has been classified as insufficient by various agents, with difficult access to palliative care and hospital referral being put on the centre stage as the most relevant aspects.

As professionals of Palliative Care (PC) teams, we have also been overwhelmed like the rest of our colleagues from other disciplines by the new and unexpected situation generated by COVID-19. Now after having obtained some perspective from the weeks following 13 March, we modestly dare to share some of our experiences and reflections in order to suggest some lessons learnt that may be useful. In this article, we reflect on the difficulties in end-of-life care in these patients, on how the pandemic has affected patients previously cared for by PC teams, on the transversality of competence in PC, and assistance in end-of-life patient care when faced with a possible new epidemic.

Difficulties in end-of-life care for patients affected by COVID-19The leading cause of death for patients affected by COVID-19 is respiratory failure secondary to severe acute respiratory syndrome, which can be aggravated by other complications such as septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or heart damage.9 In cases in which respiratory failure occurs, patients need varying degrees of ventilatory support treatment, from the administration of oxygen therapy to invasive mechanical ventilation and highly complex therapies, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or exclusively symptomatic treatment.

Symptom control focuses on the treatment of dyspnoea and the symptoms typical of last stages of life such as terminal rales, fever and delirium.10 The greatest difficulty in symptomatic management by professionals who are not experts in the management of these situations is their lack of familiarity with the indication and use of opioids, benzodiazepines, or neuroleptics in end-of-life situations. To partially remedy this deficit, "rapid treatment guidelines" for the symptoms have been developed,10,11 which have been widely disseminated among professionals through official information channels, as well as on social networks.12 The use of these guidelines is an element of inappropriate homogenization of medical care when the guidelines are not balanced with experience in the use of these drugs and their adaptation to the individual situation of the patient and their prognosis. No data exists on palliative sedation in patients with COVID or on its adequate indication in relation to the standards of the scientific community, but we do have testimonies of the difficulties arising.13

The diagnosis of COVID-19 is associated with the indication droplet and contact precautions.8 Isolation and the shortage of PPEs have led to the absence of contact between the patient and his closest family environment in all healthcare settings, as well as between the family members and the healthcare team, and the healthcare team with the patient. New technologies have partially compensated for this contact deficit, and telephone/video call initiatives have been extended to take part in a visit or to share medical information of the patient with family members. This scenario together with the rapid poor evolution of some of the patients has made it difficult, in many cases, to establish a bond of trust between professionals and the family members and/or some of the patients. Although gratitude for a communication channel has generally been expressed by patients and family members alike, we still do not know the real impact it has had on helping family members to adapt to the disease process or its effect on the grieving process in the event of death. Nor is it known how it is affecting the professionals themselves, who are not used to telephone management of serious medical issues, especially in end-of-life situations.

The requisite isolation and lack of PPEs when the pandemic started, has greatly influenced the circumstances surrounding the death of many of the patients.14 It was not until several weeks after the start of the pandemic that some institutions, such as nursing homes, social healthcare facilities or hospitals, modified their action protocols to allow a ‘properly protected’ family member to be in confinement with the end-of-life patient. A patient dying alone and without the possibility of farewell or visual or physical contact between patient and family is repeatedly cited by health workers as one of the most vexing factors professionally.

The abovementioned disclosures have enabled the need for emotional care for patients, families and professionals to be quickly identified, and different countries have drawn up protocols for action to contemplate the multiple psychological needs.15,16 The possibility of being infected or infecting loved ones has also been described as a major source of emotional distress among health professionals in the COVID units. A professional’s involvement with repeated unexpected end-of-life situations when he/she has little experience in dealing with suffering and death is recognised as originating the need for specific psychological support.17

The transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 infection to multiple members of the same family has given rise to an unusual situation in our environment, that of tributary patients under symptoms control for COVID-19 who, in turn, have experienced the death of a close relative due to the same illness in the preceding days or weeks. This awareness of the potential seriousness of the situation has contributed to an increase in the emotional distress of many patients, who were necessarily isolated from their families. Finally, the anguish due to the separation, the lack of physical contact with the patient, and the speed with which the disease progresses have contributed and continue to cause many family members to be emotionally distressed. Additionally, the limited participation in funeral rites and ‘good-byes’ have been identified as risk factors in the appearance of a pathological mourning process.

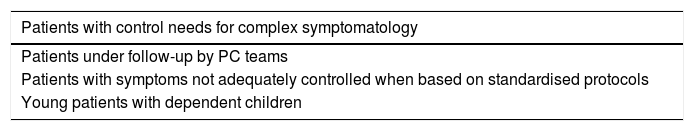

The care of patients with advanced diseases in the context of COVID-19The impact of the situation could very well be described in the words of a patient who said "Now it would really exasperate me to die from the virus… with everything I’ve battled against to accept my cancer… ". The pandemic has represented a new paradigm for those patients who are known to be more vulnerable and, therefore, have avoided going to the hospital even when it was advisable. In these circumstances, many people fear getting infected and the risk of being carriers and infecting their families and caregivers. The PC teams have converted the vast majority of the face-to-face visits into telephone attention to patients and their families despite the risk, in the most complex cases, of suboptimal symptomatic and emotional control. This telematic medical follow-up has placed an avalanche of demands on the professionals of the PC teams, with the resulting increase of physical and emotional stress. This is especially intense within the home care surroundings, due to the responsibility of a greater number of cases, the lack of PPEs and, in some cases, a limited availability of needed drugs, or complex ethical-clinical decision-making in the face of a new, abrupt, changing and complex situation. The foregoing, in our understanding, has revealed 2 key aspects that require reflection and needed improvement, brought to light by the fragile position of PCs in our healthcare system. Table 1 shows the proposed criteria18 to identify the patients with a greater need to be cared for by a specific PC team.

Criteria for intervention by specific PC teams.

| Patients with control needs for complex symptomatology |

|---|

| Patients under follow-up by PC teams |

| Patients with symptoms not adequately controlled when based on standardised protocols |

| Young patients with dependent children |

PC: palliative care.

Adapted from Sownar and Seccareccia.18.

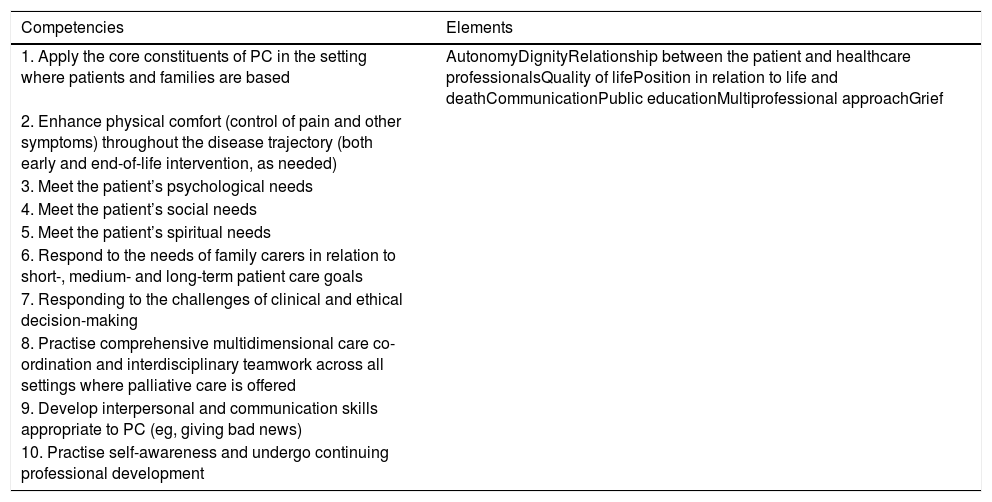

Various institutions have insisted that PC should be a transversal competence19 integrated through all the healthcare professionals, regardless of their specific area of knowledge, although perhaps placing special emphasis on end-of-life management.20,21 These competencies (Table 2) would be the identification of the end-of-life situation, the control of symptoms, the emotional, social and spiritual support, and the ability to communicate, especially bad news. This competency framework must be complemented with a personal self-awareness regarding death, as well as teamwork skills and training in bioethics.

Core competencies and constituents in PC according to the European Association for Palliative Care.

| Competencies | Elements |

|---|---|

| 1. Apply the core constituents of PC in the setting where patients and families are based | AutonomyDignityRelationship between the patient and healthcare professionalsQuality of lifePosition in relation to life and deathCommunicationPublic educationMultiprofessional approachGrief |

| 2. Enhance physical comfort (control of pain and other symptoms) throughout the disease trajectory (both early and end-of-life intervention, as needed) | |

| 3. Meet the patient’s psychological needs | |

| 4. Meet the patient’s social needs | |

| 5. Meet the patient’s spiritual needs | |

| 6. Respond to the needs of family carers in relation to short-, medium- and long-term patient care goals | |

| 7. Responding to the challenges of clinical and ethical decision-making | |

| 8. Practise comprehensive multidimensional care co-ordination and interdisciplinary teamwork across all settings where palliative care is offered | |

| 9. Develop interpersonal and communication skills appropriate to PC (eg, giving bad news) | |

| 10. Practise self-awareness and undergo continuing professional development |

PC: palliative care.

The stress to which the system has been subjected has brought out the weaknesses in PC competencies and in end-of-life care for many of the members of the COVID units of hospitals and healthcare teams in private and nursing homes. In recent months, expressions that seemed forgotten such as "death throes" or "lytic cocktail" have regained strength. This not only reveals unmet training needs, but also a difficulty of an empathic approach to include the subject of death as a reality, a natural and inescapable part of life, especially among non-expert professionals.

An important factor in symptom control of COVID-19 has been decision-making difficulties by professionals. The scarce evidence and heterogeneity of the available protocols, have led the way to difficulties in the suitableness of the therapeutic effort and, on occasions, poor control of symptoms. This has frequently been conditioned by fear and ignorance of the side effects of drugs in the context of respiratory failure.

Contributing input in the care of end-of-life patients in the face of a possible new epidemicThe challenges to improve the palliative care response during the epidemic, fall on healthcare professionals, scientific societies, and PC professionals.

PC teams must know how to interpret the complexity of these patients and position themselves as the healthcare referents in the patient’s end-of-life care. We suggest that the subsequent COVID units are linked to a PC reference team, to share in decision-making, to advise and monitor symptom control, and to quickly address emotional distress. At-home healthcare teams (including nursing homes) must incorporate palliative care at home teams to have the necessary support in symptom control and decision-making. This step will only be achieved if we are conscious not only that PC must be functionally integrated into the different teams that care for patients with advanced and life-threatening diseases, but that also this contributed input is distinguishable and it provides knowledge and skills that are PC-specific. We hope and wish that many of the PC teams in our country will also broadcast their vision, adding their experience and work elements to improving the care of patients in need of palliative care.

Let's hope that the scientific societies accept the challenge to agglomerate the knowledge surging from the pandemic and to help increase its generation and dissemination. This committal also includes continuing in their endeavours for Palliative Care to be recognised as an area of knowledge in its own right, in a formula yet to be determined, and its implementation in all the undergraduate teaching programmes of the interconnected disciplines. This will further the guarantee that healthcare professionals can acquire these end-of-life transversal competencies.

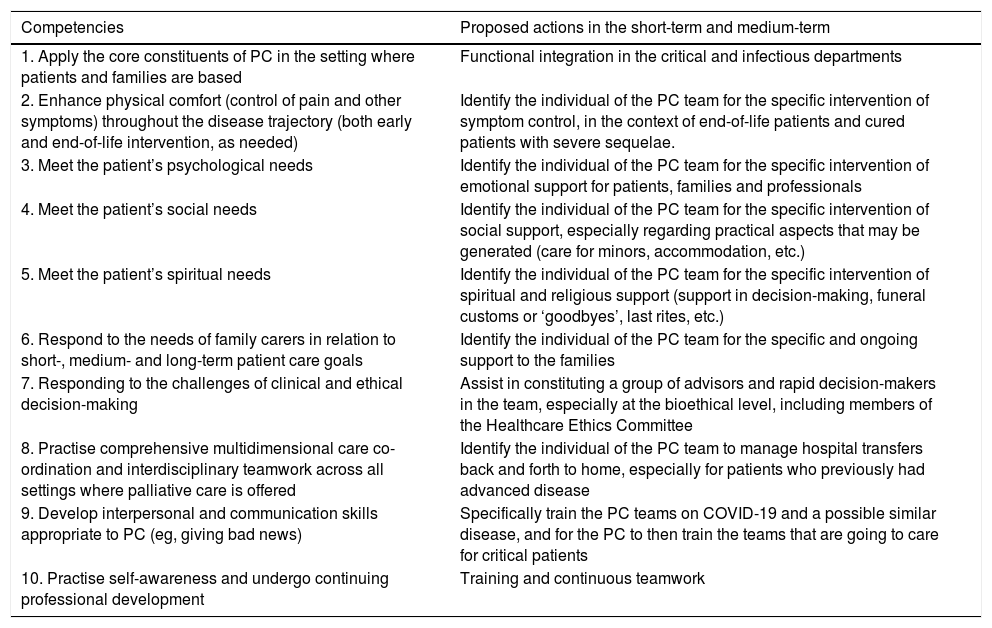

ConclusionsThe COVID-19 pandemic that we are still living at the present time is beginning to provide us with elements for reflection that we believe are interesting. In Table 3 we have provided a summary suggesting some actions that can be carried out to improve the intervention of the PC teams. In short, the abruptness with which the events of the current pandemic have occurred (and are occurring) may allow us to explain everything we have been through so far and all the aforementioned actions, but it would inexplicable if we have not learned the lesson and trip twice on the same stone.

Specific proposals when faced with new outbreaks of COVID-19 or related diseases in reference to competencies in PC.

| Competencies | Proposed actions in the short-term and medium-term |

|---|---|

| 1. Apply the core constituents of PC in the setting where patients and families are based | Functional integration in the critical and infectious departments |

| 2. Enhance physical comfort (control of pain and other symptoms) throughout the disease trajectory (both early and end-of-life intervention, as needed) | Identify the individual of the PC team for the specific intervention of symptom control, in the context of end-of-life patients and cured patients with severe sequelae. |

| 3. Meet the patient’s psychological needs | Identify the individual of the PC team for the specific intervention of emotional support for patients, families and professionals |

| 4. Meet the patient’s social needs | Identify the individual of the PC team for the specific intervention of social support, especially regarding practical aspects that may be generated (care for minors, accommodation, etc.) |

| 5. Meet the patient’s spiritual needs | Identify the individual of the PC team for the specific intervention of spiritual and religious support (support in decision-making, funeral customs or ‘goodbyes’, last rites, etc.) |

| 6. Respond to the needs of family carers in relation to short-, medium- and long-term patient care goals | Identify the individual of the PC team for the specific and ongoing support to the families |

| 7. Responding to the challenges of clinical and ethical decision-making | Assist in constituting a group of advisors and rapid decision-makers in the team, especially at the bioethical level, including members of the Healthcare Ethics Committee |

| 8. Practise comprehensive multidimensional care co-ordination and interdisciplinary teamwork across all settings where palliative care is offered | Identify the individual of the PC team to manage hospital transfers back and forth to home, especially for patients who previously had advanced disease |

| 9. Develop interpersonal and communication skills appropriate to PC (eg, giving bad news) | Specifically train the PC teams on COVID-19 and a possible similar disease, and for the PC to then train the teams that are going to care for critical patients |

| 10. Practise self-awareness and undergo continuing professional development | Training and continuous teamwork |

PC: palliative care.

This original paper has not received funding of any kind.

Conflict of interestsNone.

AcknowledgementsCátedra WeCare (Universitat Internacional de Catalunya).

Please cite this article as: Julià-Torras J, de Iriarte Gay de Montellà N, Porta-Sales J. COVID-19: reflexiones de urgencia desde los cuidados paliativos ante la próxima epidemia. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;156:29–32.