When an author’s research has borne fruit and their article is published in a biomedical journal, not only does it represent a scientific contribution to the community and a step forward in knowledge and in evidence-based medicine, but it also has a bearing on the academic furtherance of the author.1 Professional perspectives in hospitals and universities are strongly linked to scientific authorship. Currently, publications in indexed biomedical journals are the most important measurable parameter in the scales of access to a stable position for authors in the centres to which they are attached.2

Historically, the majority of authors in biomedical sciences have been men, with women being poorly represented in all fields and specialities.3 The last few decades have seen a social shift towards a large number of women being admitted into medical schools. As a result of this feminisation of medicine, it is important to note that more and more women are being named in the authorship of research and publications.1 Even so, women are still underrepresented in academic positions, especially in positions of greater responsibility.4

The aim of this study is to analyse the evolution of the percentage of female authors in articles published in Medicina Clínica over the last 11 years. Medicina Clínica is a reference journal in Spanish medicine. Its contents cover two fronts: original research papers and papers aimed at continued learning. It is a vehicle for scientific information of acknowledged quality, ranking in the second quartile (Q2), occupying 58th place out of 167 journals in the "general and internal medicine" category, according to the latest update of the Journal Citation Report (JCR).

Material and methodsPublications in the Medicina Clínica journal were accessed through open access provided by the Barcelona University Centre for Resources for Learning and Research (CRAI). A review of all the articles for the period from 2012 to 2022 was performed. All articles were listed on a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel, 2013), and then the type of study, the total number of male authors, female authors and the gender of the first and last author according to their first name was determined for each article.

For the purposes of this study the first author has been considered as the primary author and the last author as the senior author. The growth in the number of female senior authors is considered as an indirect representation of holding responsible positions in research.

When there were doubts about the authors' gender, an internet search was carried out. The author was searched for on academic or professional websites such as LinkedIn. If the search was unsuccessful, conventional search tools such as Google were used. When none of the above gave results, or the gender could not be deduced from the name because the article was written by foreign authors, it was considered unknown and the article was excluded from the analysis.

Gender refers to socially constructed roles, behaviours and identities of women, men and gender-diverse people. It influences how people see themselves and others, how they behave and interact, and how power is distributed in society. For this study the terms man/woman and male/female gender are used interchangeably and in relation to gender identification.

ResultsWe determined there were 4,229 articles, distributed among 22 volumes (vol. 138–159, both included) from 2012 to 2022 inclusive. 101 articles (2.4%, less than 3% of the total number of included studies) were removed because we could not reliably verify the gender of the authors. Of the 4,128 articles included in the study, we counted 810 originals, 345 editorials, 329 reviews, 209 special articles, 357 scientific letters, 564 images of the week, 1,248 letters to the editor and 266 others (clinicopathology-MIR conference [16], consensus conference [43], book review [three], diagnosis and treatment [72], erratum [14], clinical research and bioethics [20], clinical note [89], questions and answers in clinical pharmacology [four] and report [five]) (Fig. 1).

A total of 15,983 authors were counted over the 11 years of study, representing 8,877 (55.5%) males and 7,106 (44.5%) females. The percentage of female authors increased from 2012 to 2022 and, consequently, the percentage of male authors decreased. In 2012 there were 39% female authors, which increased to 49% in 2021. In 2022 the percentage decreased to 47% (Fig. 2).

Primary authorThe same trend is observed with primary authors, with an increase in the percentage of female authors from 36% in 2012 to 44% in 2022. Even so, the highest percentage is observed in 2021 with 48%. The percentage of men decreased from 64% in 2012 to 56% in 2022 (Fig. 3).

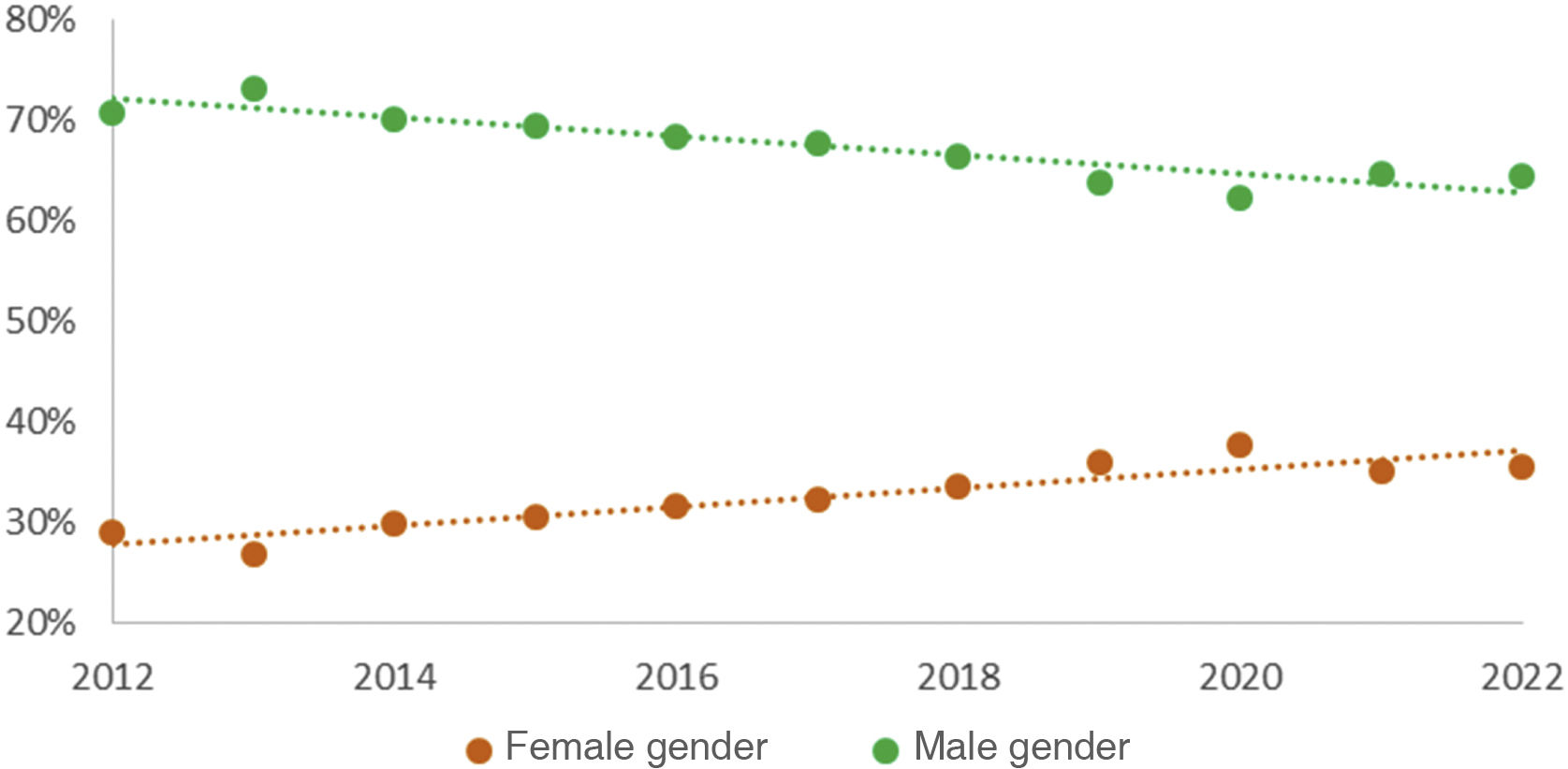

Senior authorWhen looking at the senior author of each article from 2012 to 2022, we observed a slight increase of women from 29% to 36%. It is important to note that the highest percentage of 38% was seen in the year before 2020 (Fig. 4).

The combination of genders of the authorsWe studied the number of articles with female-only authors, male-only authors or a combination of both. Although there are only subtle differences over the 11 years of the study, it results in a slight increase of 4% (from 66% in 2012 to 70% in 2022) of articles where both females and males collaborate. More interestingly, the percentage of articles written only by men decreased by 7% over 11 years (26% in 2012 to 19% in 2022), while articles written only by women showed an increase of 4% (7% in 2012 to 11% in 2022). Even so, in 2022 (356 published articles) there is still an 8% difference between articles written only by male authors (68 articles) compared to those written only by female authors (39 articles), with the former being higher (Fig. 5).

DiscussionBy analysing the articles published in the Medicina Clínica journal over the last 11 years (2012–2022), our objective was to analyse the trend of gender in the authorship of articles. In the 4,128 articles analysed between 2012 and 2022, we observe an increasing contribution by the female gender. The participation of women has increased, almost closing the gap between men and women.

According to data published on the European Union's statistical portal (Eurostat), Spain is the most feminised European nation in medicine. In the 2022/2023 academic year, women accounted for 70.6% of students enrolled in a medical degree.5 Therefore, it would be logical for the trend of female authorship to continue to increase in the coming years.

The subject of the gender gap has stimulated several studies to be published in biomedical journals. These studies show a progressive increase in the representation of women as primary and senior authors in varying specialities such as epidemiology,6 otorhinolaryngology,7 neurosurgery8 and plastic surgery,2 but in no case do they reach gender equality.

Yamamura et al.,4 analysed the trend in gender equality. This study included the different positions in authorship of scientific publications in five medical specialities (radiology, urology, surgery, gynaecology and paediatrics) and six countries (USA, Canada, UK, France and Japan) over a 10-year period (2007–2017). The percentage of women increased over the years. This increase was very significant in the primary author, especially in the specialities of urology and surgery. In contrast, the increase in the senior author was much less significant, especially in specialities with a high percentage of female professionals (paediatrics and gynaecology). This observed difference may reflect, among other things, dropping-out from the academic career early or mid-term, due for example to structural inequality.

Something similar is observed in the speciality of orthopaedic surgery and traumatology. A very recent study by Ghattas et al.9 analysed the trend of female authorship in orthopaedic literature between 2002 and 2021. They performed a cross-sectional bibliometric study on a total of 26 journals specialising in orthopaedic surgery and traumatology in the USA, and this included an analysis of 168,451 authors. The percentage of female primary authors (13.6%) was significantly higher than the percentage of female senior authors (9.9%). The study results showed an increasing trend in the percentage of female primary authors, however, the increase in female senior authors was not significant. It also noted that articles with female primary authors were significantly more likely to have a female senior author. Other articles regarding the speciality of orthopaedic surgery showed similar results.10,11

These data coincide with the results of our study, in which, based on a prestigious journal such as Medicina Clínica, it is observed that, in 2022, 44% of the articles had a woman as the primary author and 36% had a female senior author. This is in line with the articles we have commented on previously: the increase is greater in primary authors than in senior authors.

A very poor retention rate of female medical students in surgical specialities has also been observed, implying a lower representation of women in both speciality authorship and leadership positions. It appears that when choosing a speciality, women take into account the relationship with a mentor, the intellectual challenge, the rewarding nature of surgery, and the prior knowledge they may have acquired about a speciality in the degree - exposure to the speciality – rather than the prestige and financial gain men tend to consider.12 On the other hand, women find gender discrimination, the lifestyle of surgeons, and socio-cultural factors observed in surgical specialities to be a deterrant.12 For this reason, the increase of female representation in surgical specialities seems to be slower, although the trends are similar to other medical or medical-surgical specialities: the increase of female representation is more apparent in primary authors than in senior authors.13

Whitley et al.14 reviewed the publications of five high-impact urology journals and compared them with the percentage of women in the speciality of urology. Although the representation of women in the publications is still in the minority (26.3% of primary authors and 14.5% of senior authors), the percentage of publications with female primary and senior authorship is significantly higher than the percentage of women in the urology speciality. In contrast, Bernardi et al.15 concluded that women surgeons publish research at a rate proportional to the number of females involved in that speciality. The authors suggest that the disparities in leadership roles are likely due to a failure to attract women to academic surgery and failure to promote and mentor women surgeons into leadership positions.

We have observed that, although in recent years the role of primary author is becoming more equal between genders, there is still a large difference in the case of senior authors. This clearly reflects the fact that leadership positions in working groups are mostly held by men, and that women less often lead research groups. Perhaps the first step in narrowing the gender gap in these positions is to increase the representation of women in all areas of medicine and research. One of the key points to facilitate change would be the presence of transparent, merit-based criteria for eligibility to these senior positions. The existence of such criteria could inspire women to pursue these positions.16 But this gender inequality cannot be attributed solely to the lack of such criteria; several other reasons why women may choose not to pursue or accept project leadership have been described. These include maternity, work-life balance, lack of mentoring and representation, imposter syndrome or systemic gender preference.

Pregnancy, maternity and breastfeedingFor women, one of the problems influencing the decision not to aspire to positions of responsibility in the field of research and health care medicine is the fact of having children. Today, this decision marks a gender-differential path, as the intention to progress academically coincides with a period of life in which family planning is present. In the absence of structural conditions, such as care and support for offspring, many women abandon the competition and opt for a more predictable clinical career in the care sector, rather than in the field of research, be it clinical, basic or translational.4 In addition, to achieve the same position as men, women often have to meet higher demands.17

Pregnancy means facing a situation that cannot be controlled, for example it may require early leave for different circumstances in addition to maternity leave. This means that for a period of time women cannot be in charge of their professional responsibilities.18 In some European countries, and very recently in Spain too, leave after childbirth can be shared between the parents. But it is usually women who give up working and participating in research studies, because they prioritise having children and being able to care for and educate them. This has been observed during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, when female scientists significantly decreased their publication output compared to their male counterparts, among other things due to the closure of nurseries.19

Women who decide to have children while maintaining their careers often feel either pressured to work simultaneously and remotely during maternity leave in order to maintain their position, or to reduce the length of their leave. It has also been observed that mothers who choose to breastfeed abandon it earlier than recommended due to incompatibility with work.20 To improve this situation and allow women to aspire to relevant positions with the possibility of becoming pregnant, it is proposed that programmes be created to support these women with mechanisms in place to cope with the situation in the best possible way. Flexible working hours and online working would also be advantageous. All these guidelines could also promote continued breastfeeding once a woman has returned to work.20

Reconciling work and family lifeReconciliation measures make it easier to balance work and family life. Historically, women are more likely to reconcile work and family life than men, as women are more willing to sacrifice their professional life for family care. During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, it was observed that women were more likely to take on the role of caregivers for their children and sick family members than men.21 It is also known that women do more housework than men. This means that they lag behind and are more disadvantaged in their professional lives than their male colleagues at work.21

Lack of mentoring and representationOne of the reasons why women may not consider choosing a speciality or consider themselves for a leading position in research is the lack of representation of women at this level. It has already been noted that the number of female surgeons in medical school faculties is directly related to the percentage of female students who choose surgery as their career path.22 Other studies have shown that the presence of female role models and the perceived gender distribution within a speciality has a very strong influence on career choice.8

The problem of under-representation of women in research and relevant positions will disappear as the gender gap within specialities decreases. Until this point is reached, in the internship or residency, it might be interesting for a student or resident not to depend on a single mentor or tutor, but to have a gender-varied group so that they can better understand each other in different aspects and find adequate support.23 While this may be a great step forward, the pressure to serve as a role model and mentor for other women may put additional stress on the women themselves.23

Impostor syndromeImposter syndrome has been described as the feelings of a woman that she is not as qualified as her male peers, or the feelings of doubt about her own achievements or potential for success. It was initially described in women, but has been shown to be present in the vast majority of students, although it is especially prevalent in female students and ethnic minorities.24 Related to impostor syndrome is the observation that women tend to be more lacking in confidence than their male peers, making it more difficult for them to present their projects and self-promote.24 As a consequence, they would receive less funding to carry out their scientific work and, consequently, less prestige. To minimise impostor syndrome, it is important that mentors and faculty role models empower women more during their training, so that they have more confidence in themselves and their abilities.23

Systemic gender preferenceIn the present study, although the tendency is for there to be gender variety in the majority of articles published in the Medicina Clínica journal over the past 11 years, in 2022 we observed a higher number of articles published solely by male authors (19%) compared to solely by female authors (11%). This can be attributed to the trend towards gender homophily, described as a higher frequency of co-publication of men with men, and women with women, than would be expected by chance.25 This could be caused by women themselves seeking to avoid harassment or sexism from men.26 Or even by men because of possible discrimination against women in recruitment to research groups.25

Broderick et al. studied the gender dominance of the first author in shared primary authorships, in which the primary authors have contributed equally to the study, but it is the first author who receives the most credit.27 The authors show that men tend to take the position of first author in shared authorships with two or more scientists, combining men and women. Inequality is thus shown for women authors, implying a lower chance of receiving credit, academic positions, project funding and awards.3 One way to reduce these gender inequalities in the first position in shared primary authorships, would be for the journals themselves to require authors to explain how the order is decided in each case.28 Or even for the journals themselves to have standardised guidance on how to make this decision.28 In contrast, Baerlocher et al.29 proposed eliminating the traditional method of listing authors in which the first and last authors are seen as the most significant. They suggested as early as 2007 to replace it with a system in which there are only three designations: primary author(s), supervising author(s) and contributing author(s). In each of these categories there could be more than one author. They also suggested rules for deciding who should be cited as an author and in which category each author falls.

Finally, to our knowledge, no studies have been carried out on the gender of authorship in our country. Only one recent study has been published that analyses the preferential authorship (first or last authorship) of women in articles in the Emergencias journal.30 The results of this study are similar to the present one.

Limitations of this analysis, which has used a binary system to classify researchers by name, include the possibility of excluding people of non-binary or other genders or mistaking the gender of some authors. There is also a greater likelihood of excluding publications/papers by authors with names from Africa or Asia, as these have proven to be the most difficult to determine and account for almost all of the articles discarded from the study. Even so, these should not affect the percentages, as they are expected to be evenly distributed across genders.

This study is based on counting the number of authors per article and determining whether they are in the position of primary or senior author. It is possible that during the 11 years analysed in the study, some of these researchers are repeated in the sample and therefore it is possible that this study is overestimating the number of authors involved in the research.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, between 2012 and 2022, the percentage of female authors in the Medicina Clínica journal has gradually increased from 39% to 47% in the last year analysed. It is expected that the representation of women in scientific authorship will continue to increase, as in 2022 females represented 70.6% of medical students. Even so, currently only 38% of senior authors are female, and although these figures have also improved over the last 11 years, there is still a large gender gap.

FundingThis work has not received any funding.

Ethical considerationsThe type of study did not require obtaining informed consent. It does not include analysis of individuals.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.