Although the most common symptoms of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection are respiratory, neurological manifestations have also been described, particularly among critical patients, including encephalopathy, seizures, and cerebrovascular disease.1,2

We hereby present three cases of intracranial bleeding in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) who were admitted to our unit with severe pneumonia to receive treatment with mechanical ventilation and sedation. Because of the need for prolonged intubation, all patients underwent a tracheotomy. All of them tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in a nasopharyngeal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test and, based on our unit’s protocol, were treated with lopinavir/ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, and ceftriaxone for 5 days, dexamethasone for 10 days, and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) at anticoagulant doses if their d-dimer levels were greater than 1000 ng/mL. During the examination performed on their admission to the unit, they all maintained a good level of consciousness, with a Glasgow score of 15 and no focal neurologic signs (none of them had a previous history of cognitive impairment).

The first patient was a 65-year-old man with hypertension and diabetes, in which case sedation was discontinued after 10 days of evolution due to observing respiratory improvement and, at a neurological level, a low level of consciousness, with a Glasgow score of 5. An electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed severe encephalopathy and a cranial computerized tomography (CT) scan showed a frontal, left, intraparenchymal hemorrhagic focus measuring 7 mm, associated with a perilesional edema, and another millimetric focus in the right cerebral convexity. At the time of the diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage, the blood tests peformed reflected thrombocytopenia of 95,000/µl and d-dimer levels of 1600 ng/mL, because of which treatment with LMWH at a dose of 1 mg/kg every 12 h was started, although it was subsequently discontinued.

The second case corresponded to a 64-year-old man with a history of hypertension and diabetes. After 12 days of hospitalization, sedation was withdrawn, observing an alteration in his levels of consciousness, with a Glasgow score of 6. An EEG revealed data of moderate encephalopathy and a cranial CT scan showed multiple foci of supratentorial, intraparenchymal hemorrhage in both cerebral hemispheres. In addition, blood tests reflected thrombocytopenia of 85,000/µl and d-dimer levels of 3900 ng/mL, because of which treatment with LMWH at an intermediate dose of 0.5 mg/kg every 12 h was started. Treatment with LMWH was subsequently discontinued until further progression of his condition was evidenced, at which time the Neurosurgery Department was consulted, with surgical treatment being ruled out.

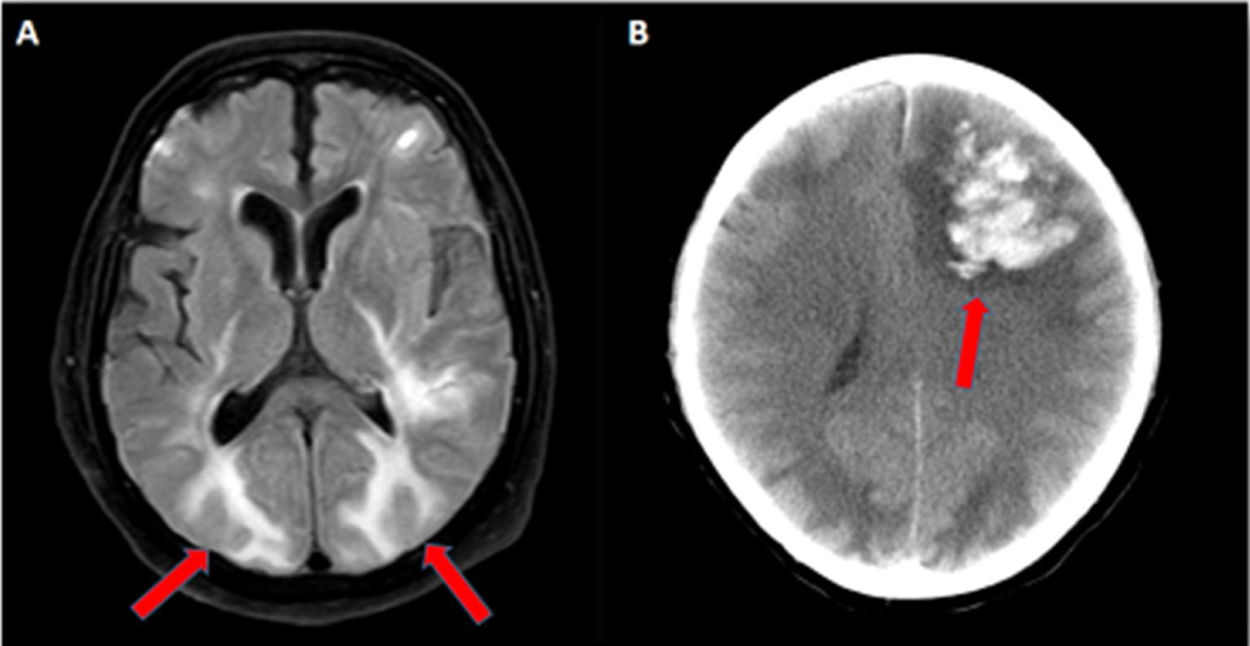

In order to complete the diagnostic study, a nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was performed, identifying a fairly similar radiological pattern consisting in bilateral involvement of the white matter, predominantly in the parieto-occipital region (Fig. 1A), associated with multiple hemorrhagic lesions, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and subcortical microhemorrhages. The subsequent clinical evolution of both patients with the supportive therapy was good.

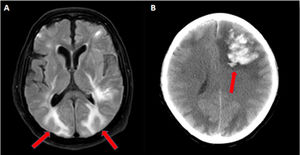

(A) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI sequence showing bilateral, subcortical, hyperintense lesions with vasogenic edema in the parieto-occipital cerebral lobes (red arrows). (B) Cranial CT showing a large, left, frontal hematoma causing midline deviation (red arrow).

The last case corresponded to a 69-year-old man who, after discontinuing sedation on day 13 of the evolution of his disease, presented with a low level of consciousness and right hemiplegia. An EEG revealed evidence of severe encephalopathy and a cranial CT scan showed generalized hypodensity of the supratentorial white matter and a large, left, frontal hematoma causing deviation of the midline (Fig. 1B). The neurosurgeon performed an emergency craniectomy to evacuate the hematoma, observing that the hemorrhage originated in the cortical arterioles, as well as friable and dark brain tissue, because of which an intraoperative biopsy was performed, identifying signs of a thrombotic microangiopathy and an endothelial lesion without evidence of associated vasculitis nor necrotizing encephalitis.

At an analytical level, the blood tests revealed d-dimer levels of 7000 ng/mL and a normal platelet count, due to which he was administered anticoagulation therapy with LMWH. The patient’s subsequent neurological evolution was good, although he presented with sequelae in the form of right hemiparesis on discharge.

A stroke can occur during the acute phase of the infection or even days and weeks following resolution of the viral phase.

Several pathophysiological mechanisms contribute to the increased risk of stroke in COVID-19 patients. The SARS-CoV-2 can infect the endothelial cells of the central nervous system, causing an inflammatory response in the blood vessels and endothelial damage, both of which, together with the thrombocytopenia present in some critical patients and the anticoagulant therapy, can contribute to the onset of microhemorrhages or cerebral hemorrhages.3–5

Because it is easy to overlook stroke in critically ill patients who are sedated and relaxed, we recommend early imaging if a patient has an altered consciousness or focal neurologic signs after discontinuing sedation.

FundingThis study has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Garví López M, Tauler Redondo MP, Tortajada Soler JJ. Hemorragias intracraneales en pacientes críticos COVID-19: reporte de tres casos. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;156:38–39.