To evaluate the epidemiological evolution and economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the European Union (EU) and worldwide, and the effects of control strategies on them.

Material and methodsWe collected incidence, mortality, and gross domestic product (GDP) data between the first quarter of 2020 and of 2023. Then, we reviewed the effectiveness of the mitigation and zero-COVID control strategies. The statistical analysis was done calculating the incidence rate ratio (IRR) of two rates and its 95% confidence interval (CI).

ResultsIn the EU, COVID-19 presented six epidemic waves. The sixth one at the beginning of 2022 was the biggest. Globally, the biggest wave occurred at the beginning of 2023. Highest mortality rates were observed in the EU during 2020–2021 and globally at the beginning of 2021. In mitigation countries, mortality was much higher than in zero-COVID countries (IRR=6.82 [95% CI: 6.14–7.60]; p<0.001). A GDP reduction was observed worldwide, except in Asia. None of the eight zero-COVID countries presented a GDP growth percentage lower than the EU percentage in 2020, and 3/8 in 2022 (p=0.054). COVID-19 pandemic caused epidemic waves with high mortality rates and a negative impact on GDP.

ConclusionThe zero-COVID strategy was more effective in avoiding mortality and potentially had a lower impact on GDP in the first pandemic year.

Evaluar la evolución epidemiológica y el impacto económico de la pandemia de COVID-19 en la Unión Europea (UE) y a nivel mundial, así como los efectos de las estrategias de control.

Material y métodosRecopilamos datos de incidencia, mortalidad y producto interior bruto (PIB) entre 2020 y el primer trimestre de 2023. Luego, revisamos la efectividad de las estrategias de mitigación y de COVID-cero. El análisis estadístico se realizó calculando la razón de tasas de incidencia (RTI) de dos tasas y sus intervalos de confianza (IC) del 95%.

ResultadosEn la UE, la COVID-19 presentó seis oleadas epidémicas. La sexta, a principios de 2022, fue la más grande. A nivel mundial, la ola más grande se produjo a principios de 2023. Las tasas de mortalidad más altas se observaron en la UE durante 2020-2021, y a nivel mundial, a principios de 2021. En los países de mitigación, la mortalidad fue mucho mayor que en los países COVID-cero (RTI=6,82 [IC95%: 6,14-7,60]; p<0,001). Se observó una reducción del PIB en todo el mundo, excepto en Asia. Ninguno de los ocho países COVID-cero presentó un porcentaje de crecimiento del PIB inferior al de la UE en 2020, y 3/8 en 2022 (p=0,054). La pandemia de COVID-19 provocó olas epidémicas con altas tasas de mortalidad y un impacto negativo en el PIB.

ConclusiónLa estrategia COVID-cero fue más efectiva para evitar la mortalidad, y potencialmente tuvo un menor impacto en el PIB en el primer año de la pandemia.

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, collecting data was a priority. The Johns Hopkins University reported over 676 million cases and nearly 7 million deaths worldwide between January 22, 2020 and March 3, 2023.1 The global annual incidence and mortality of COVID-19 in 2020, 2021, and 2022 has strongly surpassed that of other historical infectious diseases, such as HIV, tuberculosis, and influenza. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the SARS-CoV-2 virus causing COVID-19 will persist for years within the world population.

On January 6, 2021 over 20.5 million years of life had been lost because of COVID-19 in 81 countries.2 In particular, at the beginning, the pandemic found the world unprepared and caused a greater loss of years of life per capita in wealthier countries. Indeed, COVID-19-related mortality is closely linked to age,3 and the population structure in wealthier countries shows a constrictive pyramid, with 21.1% of the European Union (EU) population, for example, aged 65 years or over in 2021.4 Moreover, in developed countries, many elderly resided in nursing homes, and so were more exposed to contacts and contagion between them. In particular, among the 21 countries with highest income worldwide, the United States of America (USA) had the greatest decline in life expectancy in 2020 (1.87 years), followed by Spain, England and Wales, Belgium, and Italy.5 Already in 2021, an analysis of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita revealed an increase in inequalities between countries as a result of the pandemic.6

To fight COVID-19, common measures were implemented worldwide: pharmaceutical (e.g., vaccines and antivirals treatments); and non-pharmaceutical (e.g., masks, physical distancing mandates, and monitoring of indoor air quality). However, specific strategies were also implemented by different countries: mitigation or elimination (zero-COVID).

The mitigation strategy was implemented by most countries (e.g., EU; Brazil; UK; USA). It aimed to reduce incidence, mortality, and morbidity to levels that did not collapse the healthcare system, while not disrupting economic and social life. The objective was to flat the epidemic curve and achieving herd immunity in the population with public health interventions focused on protecting vulnerable and high risk groups, while allowing transmission among low risk groups.7 The term ‘herd immunity’, as defined in 1923,8 refers to the state where a sufficiently large proportion of the population is immune, making it challenging or even preventing the transmission of an infection. Such immunity can be acquired through previous infection, vaccination, or a combination of both (hybrid immunity). The zero-COVID strategy was implemented by a minority of countries: Australia, China, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, and Vietnam. It involved implementing very restrictive policies and measures to achieve zero incidence within the territory where applied.9

Previous reviews have described different aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic, but none of them has comprehensively examined both epidemiological and economic data, and how control strategies influenced them. The current work aims to review the epidemiological evolution and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the EU and worldwide, and the effects of the principal control strategies (mitigation and zero-COVID) on them.

Material and methodsWe performed a descriptive analysis of the published epidemiological data on COVID-19 of the EU and the world from January 1, 2020 to March 31, 2023. We reviewed the periodical publications of the World Health Organization (WHO), European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Our World in Data (OWID), and Johns Hopkins University. To minimize the influence of notification delays, we collected the data on April 15, 2023. In particular, OWID reported the data on COVID-19 cases and deaths from the WHO. The WHO published updates on cases and deaths on its dashboard every week for all countries.10 From January 1, 2020 to March 21 2020, data were sourced through official communications under the International Health Regulations (IHR, 2005), complemented by publications on official ministries of health websites and social media accounts. Since 22 March 2020, data were compiled through WHO region-specific dashboards or direct reports to WHO. The source of our figures was OWID.11

We based our study on the OWID definition of confirmed cases: the ones with a PCR or an antigen test in their dataset.12

To avoid any bias linked to small population, we only considered the effect of the mitigation and zero-COVID strategies in countries with a large population, those with more than five million inhabitants. Specifically, EU countries, Brazil, UK, and USA and most of the remaining countries in the world were mitigation countries, and Australia, China, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, and Vietnam were zero-COVID countries.13

We analyzed the following aspects: (1) the evolution of the incidence of new daily COVID-19 cases, expressed as a 7-day rolling average; (2) the distribution of cumulative incidences of new COVID-19 cases in the countries that have reported the highest number of cases between January 1, 2020 and March 31, 2023; (3) the evolution of new daily COVID-19-related deaths, expressed as a 7-day rolling average; (4) the distribution of cumulative mortality from COVID-19; (5) the evolution of the excess of mortality in 19 countries of the EU for the years 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023 up to week 15, in relation to the mortality observed in the pre-pandemic years and (6) the economic impact through the evolution of the GDP using data from the World Bank.14

We calculated crude rates per million inhabitants, except for the cumulative incidence of cases, which was calculated per 100 inhabitants. We evaluated the effectiveness of the two principal control strategies on incidence and mortality, by analyzing the incidence rate ratio (IRR) of two rates and its 95% confidence interval (CI). We used MedCalc Statistical Software for these calculations.15 For GDP growth comparisons, we choose EU countries average as control (all EU countries followed the mitigation strategy), and evaluated how many zero-COVID countries performed worse. Chi-square test with Yates’ correction was used and when we observed a zero value, we used an appropriated chi-square test calculator.16

Institutional review board statement: Ethical review and approval were waived because this study is only based on published epidemiological data.

Informed consent statement: Patient consent was waived because this study is only based on published epidemiological data.

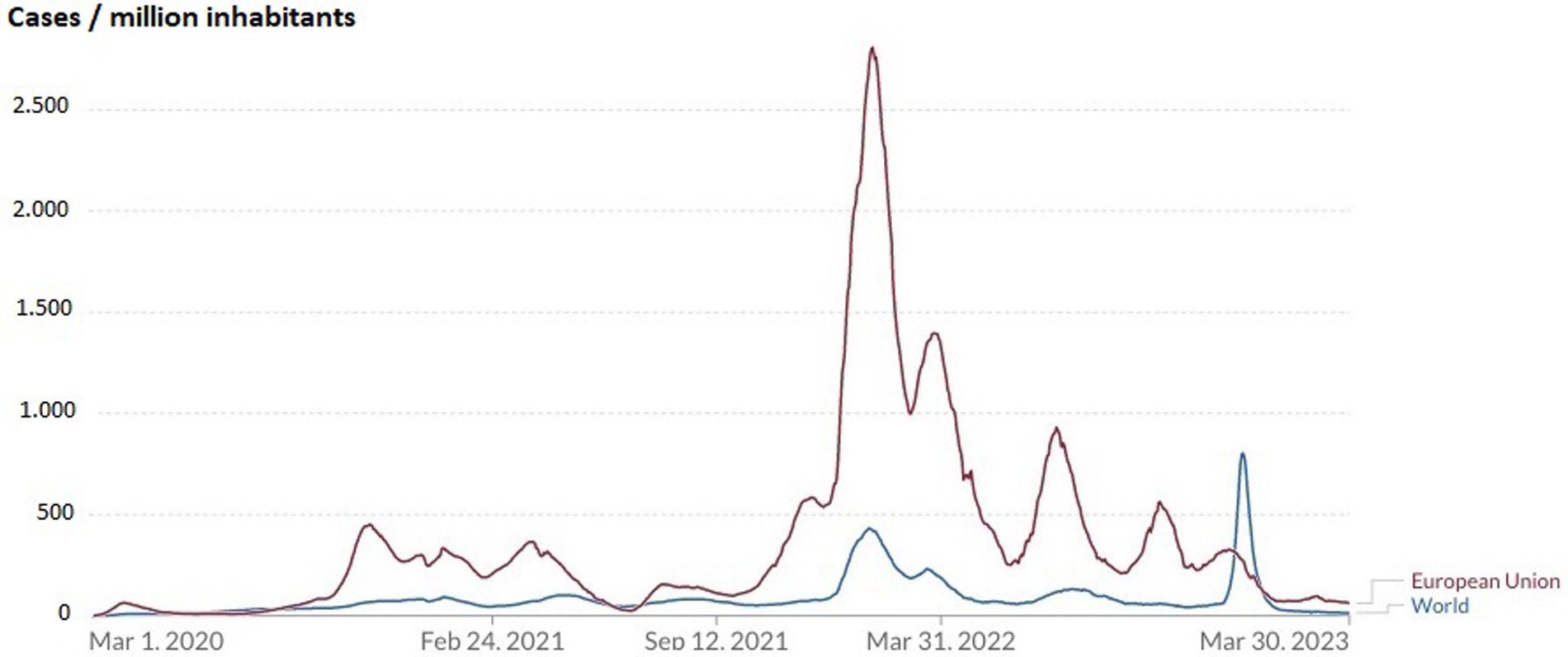

ResultsEpidemiological data: incidence and effect of the control strategies on itIn our study period, 182.47 million cases were registered in the EU (405,472/million inhabitants), and 760.77 million worldwide (95,440/million inhabitants) (IRR=4.25; [95% CI: 4.22–4.28]; p<0.0001). The evolution of the COVID-19 incidence in the EU and worldwide showed different epidemic waves, with a first one occurring in March–April 2020 (Fig. 1). As a result of this first wave, on January 30, 2020, the WHO declared the pandemic a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”.17 To better manage the health crisis, in Spain for example, a “State of Alarm” was decreed (Royal Decree 463/208 of March 14, 2020), leading to a prolonged lockdown that lasted until the end of June 2020. EU countries that implemented this measure experienced a sudden decrease in incidence. In zero-COVID countries, where the lockdown was much longer, the incidence was maintained low.

Evolution of the incidence of new daily cases of COVID-19 per million inhabitants expressed as a 7-day rolling average in European Union and worldwide, from March 1, 2020 to March 31, 2023.

In total, in the EU, there were six incidence waves of COVID-19. The sixth, at the beginning of 2022, was the largest, with an incidence of 2815/million inhabitants, accumulating more cases than all the previous ones combined (Fig. 1). This was due to the most transmissible Omicron variant. Globally, the most pronounced wave occurred at the beginning of 2023, with an incidence of 796/million people (Fig. 1). It was due to the fact that China reported a large increase in cases with an incidence of 4125/million people on 26 December 2022 after a sudden withdrawal of the zero-COVID strategy few days before.

The evolution of cumulative incidences of new daily COVID-19 casesBy the end of March 2023, the EU had a higher cumulative COVID-19 incidence than the one registered worldwide (44.5/100 and 9.5/100 inhabitants, respectively (IRR=4.68; [95% CI: 3.74–5.90]; p<0.0001). In zero-COVID countries such as Australia, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and Vietnam, the pandemic was well-controlled until the spring-summer of 2022. Then, a pronounced increase in incidence occurred with the surge in the more transmissible Omicron variant. Finally, some EU countries, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and the USA reported the highest cumulative incidences, whereas Argentina, Brazil, China, Mexico, Peru, and Vietnam, reported the lowest (Fig. 2).

Distribution of cumulative incidence per 100 inhabitants of COVID-19 in the European Union, worldwide, and in the countries that have reported the highest number of cases from March 1, 2020 to March 31, 2023.

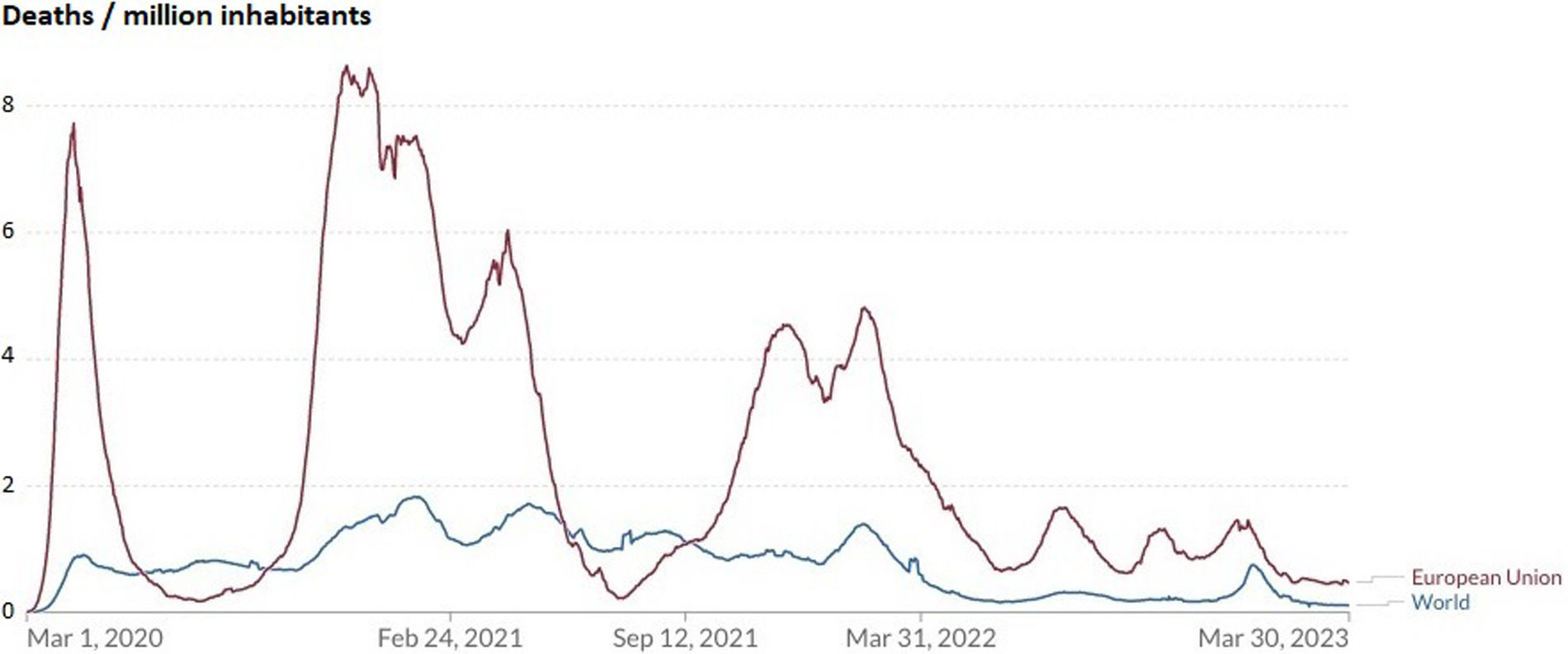

In total, there were 1.23 million deaths in the EU (2731/million inhabitants) and 6.90 worldwide (865/million inhabitants) (IRR=3.15; [95% CI: 2.92–3.41]; p<0.0001). In the EU, the highest mortality rate was observed during 2020–2021. It should also be noted that the two most populated countries in the world presented cumulative incidences and mortalities per million inhabitants that were much lower than those of the EU and the world (for example, in cumulative mortality per million inhabitants, China reported 64 and India 374 while at the World level this rate was 865 and in the EU it was 2720).

Evolution of new daily COVID-19-related deathsThe first incidence wave of COVID-19 was accompanied by high mortality rates, reaching 8deaths/million inhabitants. Then, the lockdowns imposed by many countries, that caused a sudden decrease in incidence, had the same effect on mortality. All the other incidence waves also presented high mortality rates. Globally, the highest mortality rate was observed at the beginning of 2021. Similarly to what happened for incidence, China caused another world's peak of mortality in March 2023, after a sudden withdrawal of its zero-COVID control strategy (Fig. 3).

Evolution of new daily COVID-19-related deaths per million inhabitants expressed as a 7-day rolling average in the European Union and worldwide, from March 1, 2020 to March 31, 2023.

At the end of March 2023, Peru had the highest cumulative mortality rate among all countries. Cumulative mortality in zero-COVID countries such as Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and Vietnam, was low until the spring–summer of 2022, and it increased with the surge in the more transmissible Omicron variant. However, mitigation countries had much higher cumulative mortality rates than zero-COVID countries (IRR=6.82; [95% CI: 6.14–7.60]; p<0.001) (Fig. 4).

Distribution of cumulative COVID-19 deaths per million inhabitants in the European Union, worldwide, and in the countries that have reported the highest number of cases between March 10, 2020 and March 31, 2023.

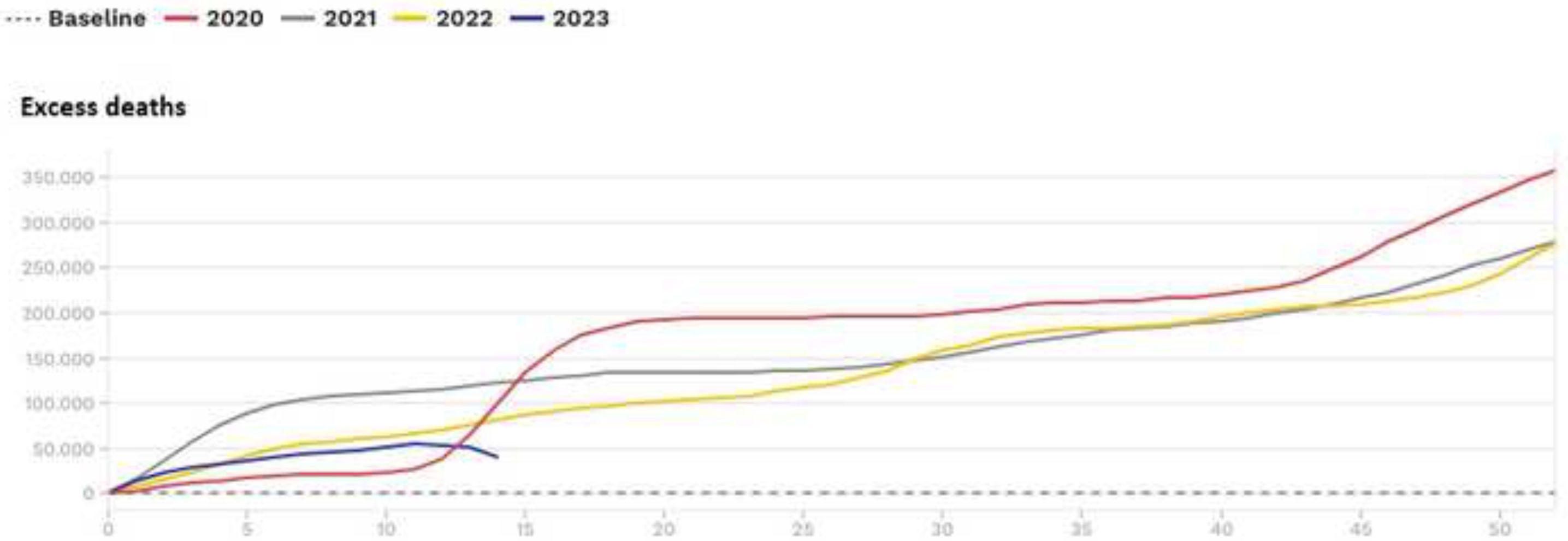

Finally, many EU countries experienced excess mortalities by COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. Moreover, they had considerable excess mortality by COVID-19 and by other causes in 2022 and early 202314 (Fig. 5).

Evolution of excess mortality in 19 countries of the European Union for the years 2020, 2021, 2022 and 2023 (up to week 15) in relation to the mortality observed in the pre-pandemic years.

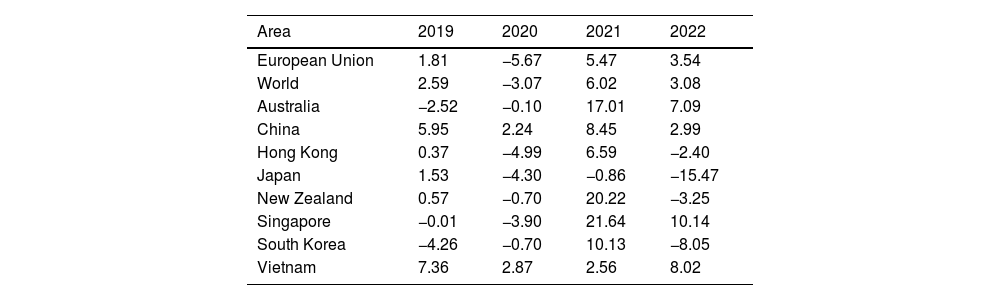

In 2020, the GDP declined by 5.67 points in the EU, and 3.07 worldwide, in comparison with 2019 (Table 1). This decrease affected all continents except Asia, where it slightly increased. South America experienced the most pronounced decline. In 2021, all continents except South America exceeded their 2019 values.18,19 The evolution was highly variable in these years in the EU, with maximum values in Ireland (6.2%, 13.6%, and 12.8%) and minimums in Spain (−11.3%, 5.5%, and 5.5%). Finally, in 2022, the EU experimented an increase in GDP of 3.54%.20

Evolution of percentage of the annual growth of gross domestic product in relation to previous year in the European Union, worldwide, and in zero-COVID countries (2019–2022).

| Area | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union | 1.81 | −5.67 | 5.47 | 3.54 |

| World | 2.59 | −3.07 | 6.02 | 3.08 |

| Australia | −2.52 | −0.10 | 17.01 | 7.09 |

| China | 5.95 | 2.24 | 8.45 | 2.99 |

| Hong Kong | 0.37 | −4.99 | 6.59 | −2.40 |

| Japan | 1.53 | −4.30 | −0.86 | −15.47 |

| New Zealand | 0.57 | −0.70 | 20.22 | −3.25 |

| Singapore | −0.01 | −3.90 | 21.64 | 10.14 |

| South Korea | −4.26 | −0.70 | 10.13 | −8.05 |

| Vietnam | 7.36 | 2.87 | 2.56 | 8.02 |

Differences were observed in the evolution of the percentage of the annual growth of GDP in the EU (where all countries followed the mitigation strategy), and in zero-COVID countries. In 2020, none of the eight zero-COVID countries presented a GDP growth percentage lower than the EU average (-5.67%), and in 2022 five of these countries presented a worse value than those of the EU (3.54%) (p=0.054) (Table 1).

DiscussionThe COVID-19 pandemic has strongly affected the world. In this study, we analyzed its strong epidemiological and economic impact in the EU and worldwide. Moreover, we show the effects of the two main control strategies.

Epidemiology: incidence, mortality, and effect of the control strategies on themThis work highlights the apparent contradiction between the evolution of COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates especially during 2020–2021, revealing relatively low incidences in comparison with the mortality rates. Moreover, because of varying protocols and challenges in the attribution of the cause of death, the real death toll may have been three times higher than the officially recorded data, particularly during the initial two years.21

This divergency is very clear for example in the first wave in the EU. To understand it, it is crucial to consider the limited availability of diagnostic tests during the early months of the pandemic, which resulted in a significant under-detection of cases. Also, many individuals were asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic, often remaining undiagnosed.22 Moreover, campaigns such as the “Stay at Home” initiative, apart from reducing the transmission, also limited access to healthcare resources, thereby contributing to the underestimation of the actual incidence. A better estimation of the incidence was given by the progressive improvement of the pandemic surveillance with the development of better detection and monitoring systems. However, because of the differences in the use of these systems between countries, there were varying degrees of under-reporting and, by the end of March 2023, the cumulative COVID-19 incidence was highly variable. In Peru, for example, the data showed important discordances, with low cumulative incidences coinciding with high mortality rates.23

Despite these discordances, the cumulative incidences and mortalities in EU are much higher than those observed worldwide. In particular, zero-COVID countries (all outside EU) detected a lower incidence and mortality, and China, a country with vast population (more than 1400 million inhabitants, equivalent to 17.7% of the total world population) had a great influence on the data. However, these differences could be due to different control strategies.24 However, China and India have 36% of the world's population and an underreporting of epidemiological data would affect the results of this study, especially by increasing the incidence and mortality in Asia and worldwide, probably not so much the comparisons between the mitigation and zeroCOVID strategies since India was based on mitigation and China on zeroCOVID.

The excess of death in several EU countries was high even when the COVID-19 mortality decreased. Indeed, some authors suggested that the full impact of the pandemic has been much greater than what indicated by reported deaths caused by COVID-19 alone. For example, the large number of COVID-19 cases overwhelmed the health systems leading to the under-diagnosis of various pathologies and delays in patient follow-up. Further research is warranted to help distinguish the proportion of excess mortality that was directly caused by COVID-19 and the one that was an indirect consequence of the pandemic.25

In agreement with our observations, other authors showed that countries that adopted the zero-COVID strategy experienced mortality rates approximately 25 times lower than countries that opted for the mitigation strategy.26 Therefore, the former showed better results by reducing incidence and mortality during the first two years of the pandemic. Finally, the advantages of this strategy ranged from short-term, such as limited virus infections, hospitalizations, and deaths; to medium-term, such as reduced presence of other infectious diseases; and long-term, such as low incidence of long COVID.27 The latter is emerging as a frequent cause for medical consultation. A meta-analysis has estimated that 80% of COVID-19 cases develop one or more symptoms beyond 2 weeks following acute infection.28 In a recent study, at least 5–10% of subjects surviving COVID-19 develop long COVID and recovery is extremely rare during the first two years, posing a major challenge to healthcare systems in the upcoming years.29

However, the zero-COVID strategy also led to significant individual and social costs.20 Most of zero-COVID countries generally performed a gradual and highly controlled transition to a new living-with-COVID phase by relaxing control measures while intensifying vaccination efforts.30 However, in 2022, after the Omicron wave, in South Korea for example, where older people had a low vaccination coverage, mortality was very high in this age-group.31 Moreover, in China, COVID-19 incidence and deaths strongly increased after swiftly lifting a long and strict zero-COVID policy in January 2023, in coincidence with the Chinese New Year, favoring travels and overcrowding. Prior to this decision, a study estimated that eliminating the “zero-COVID” policy, which the WHO considered unsustainable over time,32 could lead to 1.55 million deaths.33 While it appears that this figure has not been reached, doubts persist about the veracity of the mortality data reported by China.34

The mitigation strategy has been, in general, more respectful with human rights.35 Countries that employed this strategy, after the Omicron wave, transitioned to a “new normality” where cases were no longer isolated and contacts were not required to quarantine. The high level of immunity achieved in these countries has justified the strategic shift: over 90% of the population aged 12 or above fully vaccinated, history of prior infections, and circulating variants. Indeed, the impact of the pandemic on health systems was much lower than before, despite transition to the “new normality”. However, some countries, like the US, Brazil, and the UK, experienced high incidence and mortality rates because of the denialist position of their political leaders that minimized the relevance of the pandemic and therefore did not apply enough control measures.36 Moreover, among some countries, the low vaccination coverage and limited measures of prevention and control among the oldest people favored a high mortality. Efforts are now focused on protecting the most vulnerable individuals and areas, monitoring severe cases, and maintaining control over the emergence of potential variants.37

Economic impact: GDP and effect of the control strategies on itGDP is a measure of the economic activity, defined as the value of all goods and services produced minus the value of any goods or services used in their creation. Calculating the annual growth rate of GDP volume allows comparing the dynamics of economic development both over time and between economies of different sizes.38

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a reduction in GDP and a collapse of the stock market, resulting in a crisis and the greatest economic recession since World War II in EU and globally.39 By continents, only Asia presented an increase of GDP in 2020 and 2021. These results could be explained by the positive influence of several Asian zero-COVID countries as China (the second economy in the world), South Korea, and Vietnam in 2020; and Hong Kong and Singapore in 2022.

In countries with high mortality, the implementation of full or partial lockdown measures and other restrictions aimed at preventing the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and alleviating the pressure on overwhelmed healthcare systems, have also led to negative economic consequences: a decline in per capita consumption; a slowdown of global economic activity; a reduction in operations or the close down of many companies; job losses; a negative impact on service providers and manufacturers; a decrease in agriculture and food industry; and a decline in education and sports industry, and in the entertainment sector.40

There has also been an increase in socio-economic inequalities.6 Indeed, the fiscal response to the COVID-19 emergency has required a significant increase in both public and private debt. Such fiscal response has been substantially large in most high-income countries and limited or non-existent in low-income countries. Moreover, low-income countries will likely require more time to recover from it. These discrepancies have greatly influenced both the initial economic impact and subsequent repercussions. Indeed, in 2020, 51 countries (including 44 emerging economies) registered a reduction in their public debt risk ratings.41

These differences between countries, together with other non-COVID-19 related factors affecting the economy in the same period (rising inflation rates, increased interest rates to contain inflation, and intensified geopolitical tensions, particularly the Russo-Ukrainian war42), makes it challenging to assess the precise economic impact of the pandemic.

Finally, data from the World Bank indicates that countries that adopted the zero-COVID strategy have experienced a lower negative impact on their GDP in the first year of the pandemic, in comparison to countries adopting the mitigation strategy.43 However, in 2022, five zero-COVID countries performed worse in their annual GDP growth percentage in comparison with EU countries. Therefore, it seems that the zero-COVID strategy was not efficient in decreasing the economic impact of COVID-19 everywhere; however, it delayed it.

The role of vaccinesVaccines played an important role in the control of the pandemic. In general, vaccination reduces the risk of hospitalization and death, especially in high-risk situations, such as elderly care homes.44

Unfortunately, in 2020, vaccines were not available and the mortality was very high, especially in mitigation countries. In early 2021, those countries began implementing vaccination programs that effectively reduced mortality rates from COVID-19. On the contrary, zero-COVID countries, having a better epidemiological situation, gave the priority to maintaining strict measures until vaccines could be fully available. Therefore, in most of these countries, the sudden increase in incidence and mortality caused by the Omicron variant in spring-summer 2022 was exacerbated by the limited vaccination coverage.

Experts have estimated that to achieve ‘herd immunity’ with COVID-19, transmission would need to be limited beyond 70% and a large global vaccination coverage45 should be ensured. This is currently not possible for several reasons. First, SARS-CoV-2 vaccine protection is temporary; second, while current vaccines are extremely beneficial, they are not effective in preventing infection; third, despite the WHO COVAX strategy (focused on accelerating the development, production, and equitable access to COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines), vaccine availability is limited by several factors (price, distribution capacity, and administration) in regions with precarious healthcare systems; then, there is the risk of the emergence of highly transmissible or vaccine-resistant variants; and finally, there are many mild cases that may not confer lasting immunity. Therefore, currently, the Vaccine-plus action seek to sustain low infection rates through a combination of vaccination, public health measures, and financial support measures.46–49

How to improve COVID-19 control today?When facing health crises, resource allocation influences the number of cases and deaths in the short and medium term. These resources should rely on surveillance, prevention, and control programs of proven quality, that combine pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures with adequate economic budgets. These programs must be regularly evaluated to correct dysfunctions, and their economic costs depend on the existence of up-to-date response plans and previous investments in healthcare services. Social assistance also plays an important role in the control of diseases since, as in the case of COVID-19,50 the most socio-economically disadvantaged population is often the most affected. Already in 1914, Biggs stated that “Public health can be bought, and each country can determine its own mortality rate”.51 This notion was further supported by the publication of “How much tuberculosis do we want?” which, in response to the increasing incidence of tuberculosis, it was argued that the control of a disease depended on the definition of public health priorities and the resources invested.52

On May 5, 2023, the WHO emergency committee officially declared the end of the “Public Health Emergency of International Concern”53 that had been in force for COVID-19 since January 30, 2020. However, the committee remarked that the pandemic still poses a global threat. Considering all the factors discussed above, together with the existence of a partially unknown animal reservoir, eradicating SARS-CoV-2 in the short to medium term does not appear feasible. To end this persistent global threat to public health, it is advisable to follow the recommendations of experts, such as those recently published after a Delphi consensus carried out by a multidisciplinary panel of 386 academic, health, and non-governmental organization; governments; and other experts in COVID-19 response.54

Finally, on the basis of our analysis, in combination with previous data on different health crises, to achieve effective control of COVID-19 or other potential future pandemics, we recommend two complementary approaches:

- 1)

Reduce the incidence of infection as much as possible, particularly among vulnerable populations who are at higher risk of severe illness, while closely monitoring the potential emergence of new variants. In particular, as in any large outbreaks, the communication strategy is key to raise awareness and obtain people's collaboration, particularly considering the pandemic fatigue after enduring more than three years of limitations. It is essential to explain that the disease will not disappear in the short term and that adapting to new routines of social interaction is necessary, and these may vary depending on the incidence of the infection. In this context, and although most preventive measures may no longer be necessary in the current scenario, it is important to remain alert to potential spikes in infection.

- 2)

Achieve a better control over the virus with a high level of immunity, which effectively minimizes the number of susceptible individuals. To accomplish this, it is essential to improve the coverage vaccination and to develop vaccines that are effective in preventing infection. It is equally important to ensure that vaccines reach every country worldwide, without discrimination, while safeguarding proper pharmacovigilance. These type of measures require economic investments, but they are profitable in terms of health and necessary to minimize economic crises. By achieving high vaccination coverage, especially with sterilizing vaccines, we can stop the global impact of COVID-19.

This study presents several limitations. As for the epidemiological analysis, there have been different degrees of detection and notification of cases and deaths. Furthermore, because of the difficulty in adjusting rates with poor demographic data in some zero-COVID countries, we calculated crude rates. As for the economic analysis, the GDP is a useful indicator of a nation's economic performance, and it is the most commonly used measure of well-being. However, it has some important limitations (for example, the failure to account for or represent the degree of income inequality in society55), and confounding factors. COVID-19 can directly affect GDP but also other problems, such as political issues, aging, a drop in domestic consumption, and yen depreciation in Japan.56,57 Also, it was difficult to evaluate the maintenance of the control strategies during the years and even among different regions of single countries.58 Therefore, the available epidemiological and economic data for the COVID-19 pandemic, the comparisons between countries, and the analysis of the effectiveness of the control strategies must be considered indicative. Finally, the data on the excess of mortality were only available in EU countries, so no comparison was possible with zero-COVID countries or worldwide; and the limited number of zero-COVID countries makes it difficult to perform statistical comparisons. A bias due to low incidences and mortalities reported by India and China, the two most populated countries in the world, must also be considered.

ConclusionsSARS-CoV-2 has a zoonotic origin and generated an unexpected pandemic with millions of cases and deaths in the period 2020–2023. The zero-COVID strategy was more effective in avoiding mortality and had a lower impact on GDP in the first pandemic year.

On the basis of our results and previous observations (e.g., SARS in 200359), we conclude that the zero-COVID strategy might be a better option for coping with possible future global crises caused by new transmissible diseases with high incidence and case-fatality rates. The mitigation strategy instead could be appropriate for old or new infections with lower epidemiological repercussions. In both cases, vaccine coverage is crucial for reducing mortality after the withdrawal of most preventive measures. Finally, we believe that this work could help in the adoption of more effective and efficient control measures in response to future pandemics.

The low incidences reported by China (zero-COVID strategy) and India (mitigation strategy) probably undervalue the impact of the pandemic in Asia and globally and not so much the comparisons between both strategies.

FundingThis research received no external funding.

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, JAC, JMB, JPM, AM, JMJ; Methodology, JAC, JPM; Validation, JAC, AM; Formal analysis, JAC, JMB; Investigation, JAC, JMB, JMJ; Writing-original draft preparation, JAC, JMB; Writing-review & editing, JAC, JMB, JPM, AM, JMJ; Supervision, JAC.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Thanks to Valeria Di Giacomo, from ThePaperMill, for her accurate revision.