Assess if there is a significant association between being bullied and presenting depressive symptoms.

Materials and methodsIn the March–October period of the present year, 8–16-year-old children and adolescents that attended psychiatric consultation for the first time in Dr. Eleuterio González Hospital were included in this study. Test Bull-S was used to determine the presence of bullying (Victim subtype); to evaluate depression 2 instruments were used according to age: Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R) for 8–12-year olds and the Birleson Depression Self-Rating Scale (DSRS) for 13–16-year olds. A total of 147 clinical patients were studied (73 women and 74 men). Data were captured in excel and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program was used for statistical analysis.

ResultsA very significant association was found between being bullied and presenting depression (X2=.289, p=.0004).

ConclusionsThese data are in agreement with national and international studies, therefore, reinforcing the evidence of such association. This is why we suggest inquiring about bullying in children and adolescents whose chief complaint is depressive symptomatology.

The objective of this study is to determine whether or not there is a significant correlation between being a victim of bullying and presenting depression in the clinical population of Nuevo León, Mexico. Bullying is a term used to describe intimidations between equals. It is a form of intentional and harmful abuse (intimidation, oppression, isolation, threats, insults, beatings) from one student to another who is usually weaker, thus making him a frequent and persistent victim.1,2 School harassment in Mexico has a reported frequency of 23.9% and has been linked with psychiatric disorders in everyone implicated, with males in the majority.3 However, it is the victim who may suffer the worse consequences: anxiety, depressive symptoms and in the worst cases, suicide attempts. Reports show that victims of bullying have a greater predisposition to present depressive symptoms and psychological stress than non-victims.4 Different studies have confirmed that there is a link between bullying and depression,5–7 reaching the conclusion that people who suffer from bullying in their infancy-juvenile stage have a greater risk of presenting depression in later stages in life. 8–11

There are few studies conducted about bullying in schools and its possible associations in our country, even when this phenomenon seems to be on the rise, according to data from the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH by its Spanish acronym)12 and the Organization for Economic Co-operation (OCDE by its Spanish acronym), who reported our country as the number one in bullying.13 The present study seeks to contribute with more data on these aspects of the Mexican population, since, in order to study this phenomenon, we must take into account cultural aspects of the community.

Materials and MethodsDuring the period of March–October 2014 an invitation to participate in our study was made for all children and adolescents between 8 and 16 years old who attended our consultation for the first time at the Department of Psychiatry of the University Hospital. The patients, as well as their parents, had to agree to collaborate and a signed consent was requested, all in accordance with the rules established by the Committee of Ethics of our institution. Other requirements were that they were attending school, knew how to read and write, did not have any intellectual disability symptoms or diagnosis and had to complete their evaluation.

A sample of 139 patients was calculated, considering a confidence interval of 95%, with an estimation of error of 5%. The general census was considered as the ideal sampling method in order to increase the statistical potency. To determine the presence of bullying, victim subtype, the Bull-S Test1 was applied: to assess depression in children between 8 and 12 years old we used the CDRS-R scale14 and in the group between 13 and 16 years old the DSRS,15 these were considered the optimal according to their age group. The Bull-S Test is an elaborated instrument to measure acceptance-rejection, bullying dynamics (characteristics of the subjects involved) and situational aspects. It has a Cronbach's alpha of 0.83 for victimization conducts.16 CDRS-R is a semi-structured clinical interview, designed to measure the presence and severity of depression in children between 6 and 12 years of age. It has good internal consistency and test–retest reliability. The cutoff point of 40 was utilized, because it was considered that it best differentiates children with depressive symptomatology and the control group, with a sensitivity of 79.9% and a specificity of 99.7%.17

The DSRS scale is a useful tool for clinical and epidemiologic researches for populations between 13 and 17 years of age. It is a self-administered scale. A cutoff point of 14 was determined, giving it a balance between sensitivity and specificity, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.85. The information obtained was processed using Microsoft Excel; for the inferential and descriptive statistics, we used the statistical software SPSS 14.

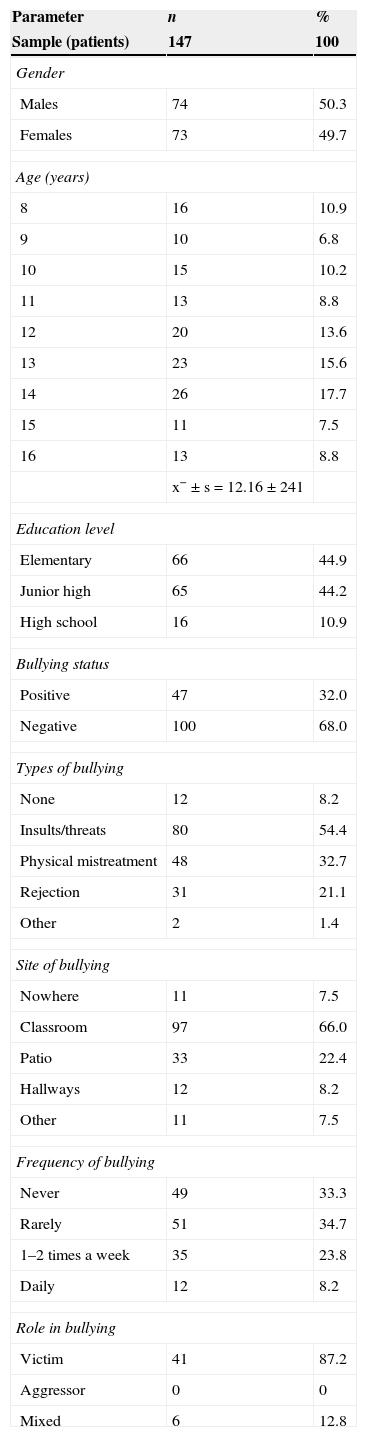

ResultsWithin the period of March–September 2014, the gathering of the sample was performed, identifying 162 patients who attended their appointment for the first time at the Child and Adolescent psychiatry consultation. From these, 5 were under 8 years of age; 4 were not attending school; 3 had an intellectual disability diagnosis; 2 did not accept to participate and 1 was eliminated due to an incomplete evaluation. Finally, 147 subjects were included in the study. The group was formed by 73 females (49.7%) and 74 males (50.3%), with a mean age of 12.16 years (SD=2.41), and a statistical mode of 14 years old. Most of the participants had an educational level of elementary school (n=66) and junior high school (n=65), only a few students had a high school level education (n=16). (Ver Table 1).

Synthesis of the general sample.

| Parameter | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sample (patients) | 147 | 100 |

| Gender | ||

| Males | 74 | 50.3 |

| Females | 73 | 49.7 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 8 | 16 | 10.9 |

| 9 | 10 | 6.8 |

| 10 | 15 | 10.2 |

| 11 | 13 | 8.8 |

| 12 | 20 | 13.6 |

| 13 | 23 | 15.6 |

| 14 | 26 | 17.7 |

| 15 | 11 | 7.5 |

| 16 | 13 | 8.8 |

| x−±s=12.16±241 | ||

| Education level | ||

| Elementary | 66 | 44.9 |

| Junior high | 65 | 44.2 |

| High school | 16 | 10.9 |

| Bullying status | ||

| Positive | 47 | 32.0 |

| Negative | 100 | 68.0 |

| Types of bullying | ||

| None | 12 | 8.2 |

| Insults/threats | 80 | 54.4 |

| Physical mistreatment | 48 | 32.7 |

| Rejection | 31 | 21.1 |

| Other | 2 | 1.4 |

| Site of bullying | ||

| Nowhere | 11 | 7.5 |

| Classroom | 97 | 66.0 |

| Patio | 33 | 22.4 |

| Hallways | 12 | 8.2 |

| Other | 11 | 7.5 |

| Frequency of bullying | ||

| Never | 49 | 33.3 |

| Rarely | 51 | 34.7 |

| 1–2 times a week | 35 | 23.8 |

| Daily | 12 | 8.2 |

| Role in bullying | ||

| Victim | 41 | 87.2 |

| Aggressor | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed | 6 | 12.8 |

Bullying was present in 32% (n=47) in the studied population, been implicated in 26 (35.6%) of the total of females (n=73) and 21 (28.4%) of the total of males (n=74); a significant difference in bullying status (present/absent) was found according to their educational level (x2=05.515, p=0.023), but not according to gender (x2=1.565, p=0.347). Regarding the type of bullying, according to the total of the studied population (n=147) where they were able to select one or more subtypes; 54.4% (n=80) reported the presence of insults and threats being recognized as the most frequent. A significant difference in the type of bullying, according to gender was not found (x2=4.878, p=0.300). As far as the place, where the subjects were able to select one or more places, 58.5% (n=86) reported the classroom as the most common place.

The reported frequencies of bullying were: “1–2 times per week” in 23.8% (n=35) and “everyday” in 8.2% (n=12). A significant difference in the frequency according to gender was not found. Out of the 147 subjects 63 (42.9%) were reported with depressive symptoms. Of these, 65.1% (n=41) were females and 34.9% (n=22) were males, finding a significant difference in the depressive status (present/absent) according to gender (X2=10–486, p=.001).

Out of the depressed subjects, 50.8% (n=32) reported the presence of bullying. The group of patients with depression and bullying consisted of 19 females (19.37%) and 13 males (40.62%). A variable independence Pearson test was performed, finding that there was a significantly greater prevalence of bullying in depressed patients (X2=17.955, p<.001). A significant difference, according to gender was not found (X2=1.125, p=.289).

In order to evaluate the association between presenting depressive symptomatology and being involved in the bullying phenomenon (subtype victim), Pearson's correlation coefficient analysis was used. We were able to find a very significant association between presenting depressive symptomatology and being a victim of bullying (r=.289, p<.01).

DiscussionWe are able to observe a prevalence of bullying of 32% (n=47) in the studied population. This number is higher than the 25% reported in a survey conducted nationwide in 2008,18 but lower than that reported in a study conducted in 2010 in a clinical population with an ADHD diagnosis of our hospital,19 where a prevalence of 56.4% was found. In general, the obtained prevalence is consistent with that reported in other studies, situating the frequency of school harassment ranging from 4.8 to 45.3%.20–23 A significant difference in the prevalence of bullying, according to gender was not found, not in the totality of the sample, nor in the subgroup with depressive symptomatology. These results contrast with those observed in a study conducted in the community population of the United States, where 3530 public school students were included for the period 2001–2002. The results showed that boys are more implicated than girls in school harassment, in the role of the offender as well as the victim, and in the frequency and intensity of the phenomenon.24 A possible explanation for this scenario is the fact that they used a clinical population for this survey, with a high prevalence of depression. As stated earlier, females who are victims of bullying present an elevated prevalence of depressive symptomatology.4,25

In the entire population, in the sub-samples of bullying victims and in the depressed patients one, the same hierarchy remains in respect to the type of bullying presented, the most frequent being insults/threats, followed by physical abuse and rejection.

This information matches the results from a study conducted in Guadalajara, Mexico in 2007,26 as well as matching data from international literature.27,28

Regarding the place where the abuse of bullied victims occurs, the order remained the same: classrooms, backyards and halls. This concurs with the information reported in the clinical population study of 2010 conducted within our institution.19 At an international level, it adheres to the same sequence of most frequent places of occurrence.29 The fact that the classroom is the most frequent place where bullying occurs, makes evident the need to provide psycho-education to parents as well as in schools, because it occurs in front of students who are considered “neutral”, but they are a part of the problem too. Even if one does not actively participate in the harassment, they could be reinforcing it under a synergic and passive effect: watching, laughing and allowing intimidation.30 It has been demonstrated that when no actions are taken, the “bullying culture” tends to perpetuate for long periods of time.31

Regarding depression, a predominance in females was observed, matching different researches where it has been proven that females show a greater tendency of depressive problems and internalized conducts in general.32–35

In patients with depressive symptomatology, a greater prevalence of bullying was detected, 50.8% (n=32), even reaching to a significant relationship between the victim subtype of bullying and depression. This association had previously been described in international articles3,16,36–39 and it has been established that it involves difficulties in the short and long term, like anxiety, irritability, low scholastic performance and suicide risk.40 A possible explanation for this outcome may be that being a victim of school harassment creates a negative cognitive style, where there are feelings of humiliation, defeat and despair, similar to other experiences of abuse,11 which negatively affects the clinical course of depression;41,42 besides this, it is possible for bullying victims to generate a victimization cycle throughout their lives.43 Finally, the biological aspect should not be left out: As a result of prolonged stress, there is usually an alteration in response to cortisol44 and a higher methylation level in the genes which transport serotonin. These effects have been associated with brain structural changes in the hippocampus, for example, and altogether can constitute paths, which explains the persistency of psychopathology throughout the subjects’ life after being a victim of bullying.45

Due to the important link found between bullying and depression, which also concurs with information reported nationally and internationally,32,33,35,46 further research is suggested on school harassment in all clinical populations of children and adolescents who manifest depressive symptomatology. Furthermore, now that there are multiple studies which have been able to stress the connection between psychopathology and bullying, further research must be done on the causality of the problem. A theory suggests that psychiatric symptomatology precedes school harassment, while others suggest that the harassment facilitates its onset.28A limitation of the present study is that, despite being able to establish a correlation between suffering from bullying and depression, the way one problem affects the other is unknown.

Having a better understanding of school harassment allows us to develop and implement the proper measures. In general, authors who have studied this phenomenon in depth recommend an integral management, going from psycho-education of everyone involved and the evaluation of the students, up to specific treatment for the associated psychopathology and the creation of programs and anti-bullying laws.47,48

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FundingNo financial support was provided.