Increase the percentage of etiological diagnosis of epilepsy (according to the classification by the 2010 ILAE) using a systematic quick guide for pediatric patients with suspected epilepsy.

MethodsAmbispective cohort study. Patients under 16 years old with suspected epilepsy were studied, and a systematic quick guide was applied to the prospective group, and later the two groups were compared. It was a convenience sample, with a study period of one year for both groups.

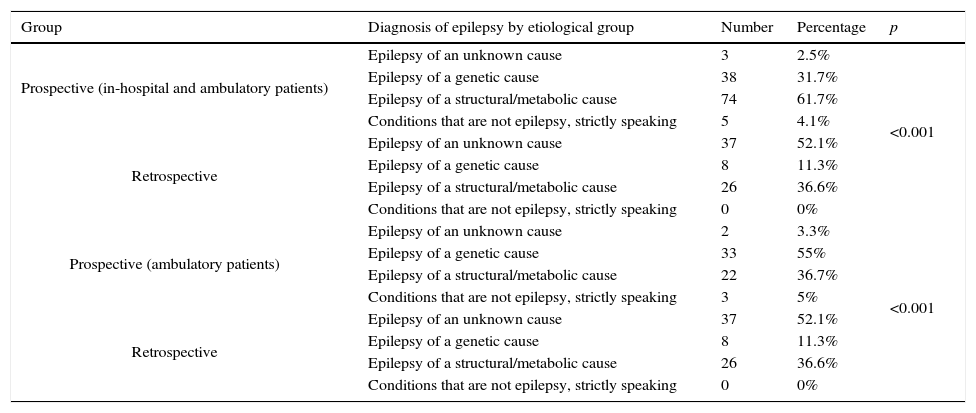

ResultsThe prospective group was 120 patients and the retrospective group 71 patients. Comparing the epileptic diagnosis by etiology groups, in the prospective group (only outpatient patients), 3.3% had epilepsy of an unknown cause, 55% had epilepsy of a genetic cause, 36.7% had epilepsy of a structural/metabolic cause, and 5% had conditions that are not epilepsy itself. Meanwhile in the retrospective group, 52.1% had epilepsy of an unknown cause, 11.3% had epilepsy of a genetic cause, and 36.6% had epilepsy of a structural/metabolic cause (p<0.001).

ConclusionsCompared to other similar studies, the etiological percentages of epilepsy increased. Using the systematic quick guide proposed, the percentage of etiological definitions of epilepsy was increased in pediatric patients.

Seizure, according to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), is the transitory occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal excessive synchronous neuronal activity in the brain.1 Epilepsy is a disorder of the brain defined as the presence of hyper synchronous neuronal activity, which is clinically expressed by any of the following circumstances2:

- •

At least two unprovoked or reflex seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart.

- •

An unprovoked or reflex seizure, and a probability of presenting further seizures over the next 10 years, similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) subsequent to the onset of two unprovoked seizures.

- •

As an integral part of an epileptic syndrome.

An epilepsy syndrome is a group of signs and symptoms which define a unique epileptic condition, made up of convulsive crises with specific characteristics, onset age, gender predominance, etiology, cognitive or behavioral comorbidity, daily variation or its link to sleep and family history. Some triggering factors are: sleep deprivation, photic stimulation, hyperventilation, etc., which has direct implications in its management, evolution and prognosis within neurodevelopment and the result of the epilepsy, genetic tests and inheritance.3

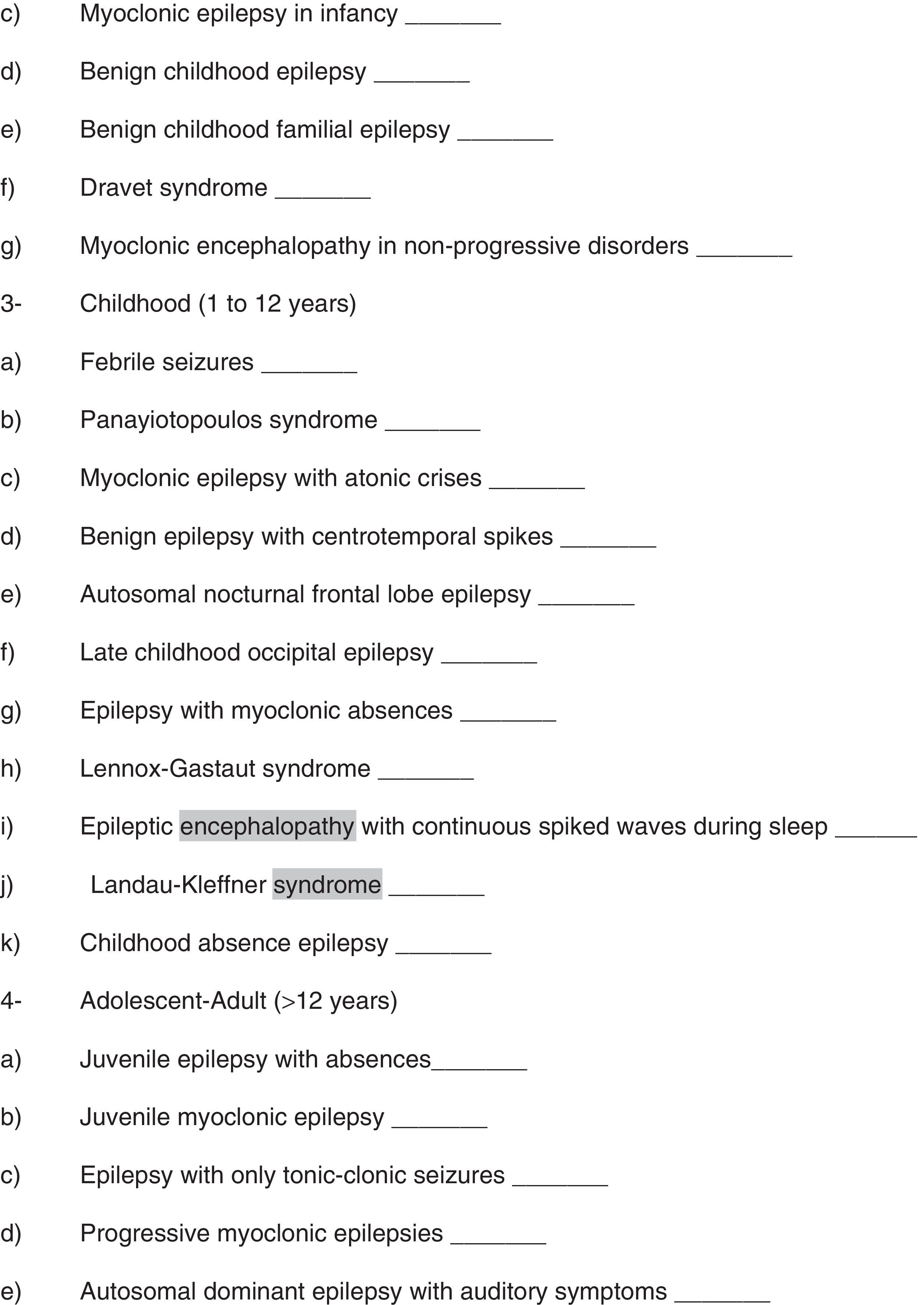

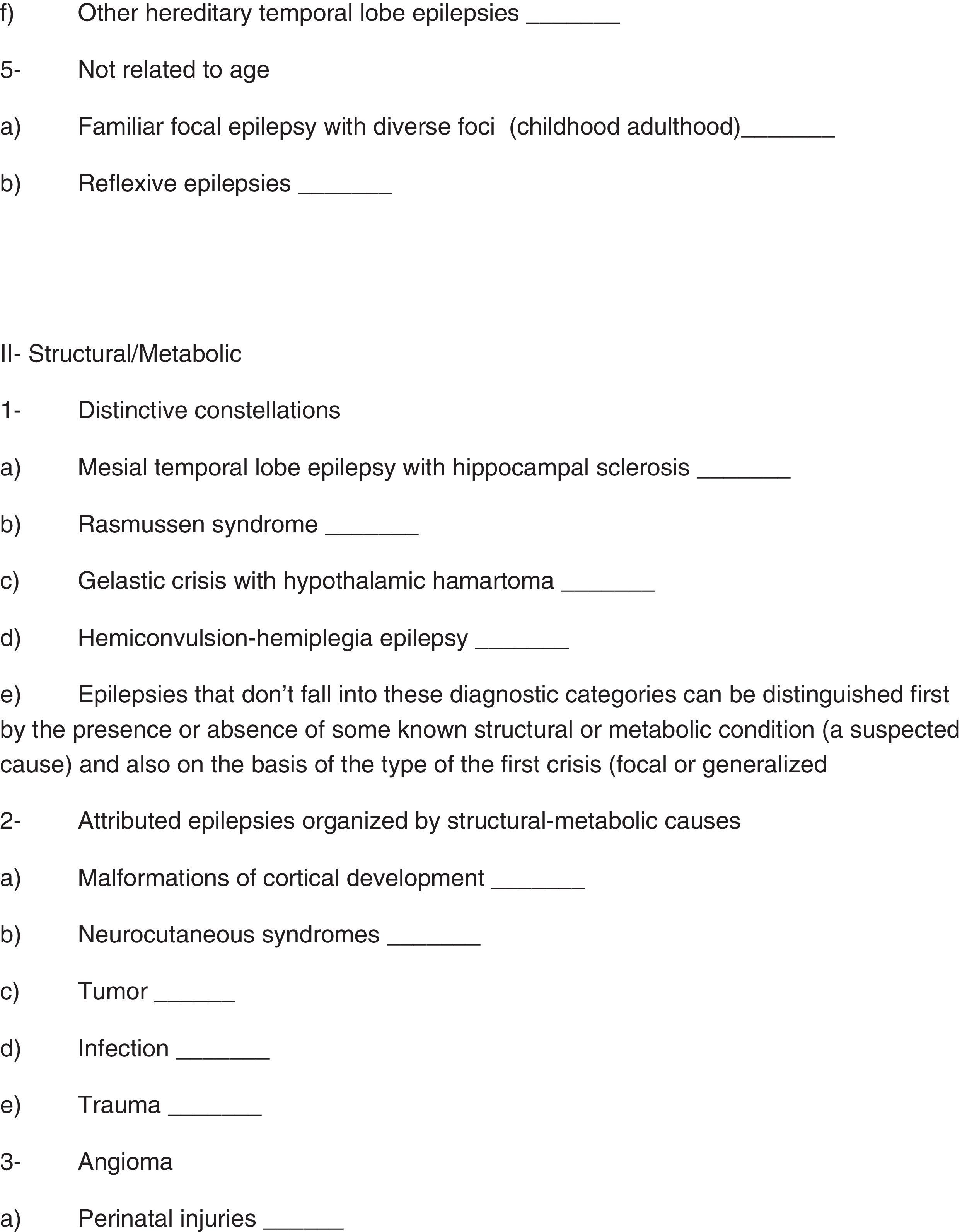

In Mexico, the prevalence in the Priority Programs for Epilepsy centers is 11–15/1000, thus this numbers suggest that in our country the number of patients with epilepsy is around 1.5 million.4 In 2010, the ILAE redesigned the classification of seizures and epilepsy crises; dividing them into generalized, focal and unknown crisis (epileptic spasms).5 Regarding to electro-clinical syndromes and other epilepsies, they were classified according to the age of onset and specific etiology as follows: genetic, structural/metabolic, of unknown causes, and in conditions which are not actual epilepsy.5

The objective of this paper was to increase the percentage of epilepsies etiologic diagnoses in pediatric patients (according to the classification by the 2010 ILAE) using a systematic quick guide in pediatric patients with suspected epilepsy.

Materials and methodsAn ambi-directional cohort study was conducted, with interventionism in the prospective group (with the application of the proposed systematic quick guide). The sample size was at convenience, all patients who arrived during one year in both groups.

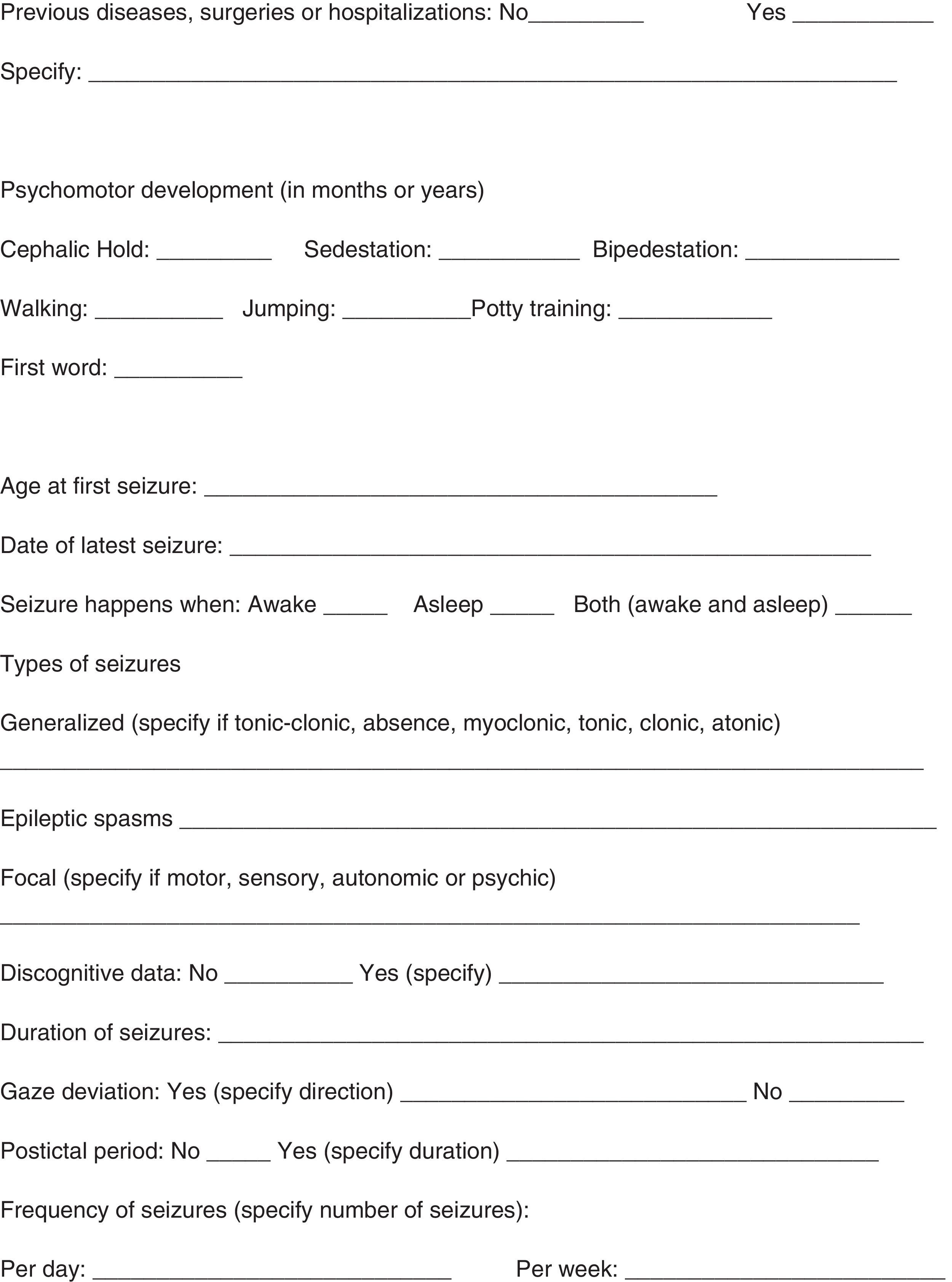

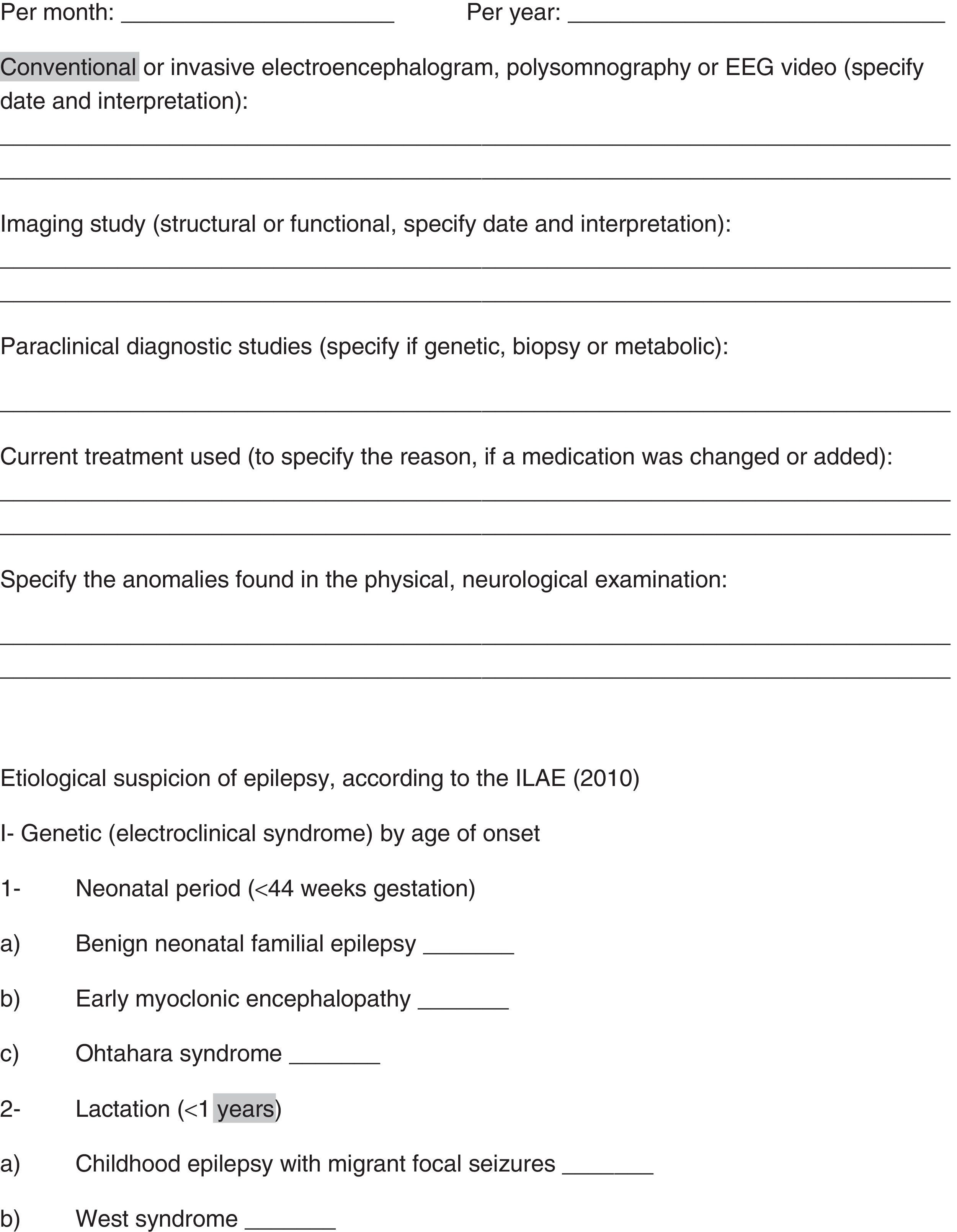

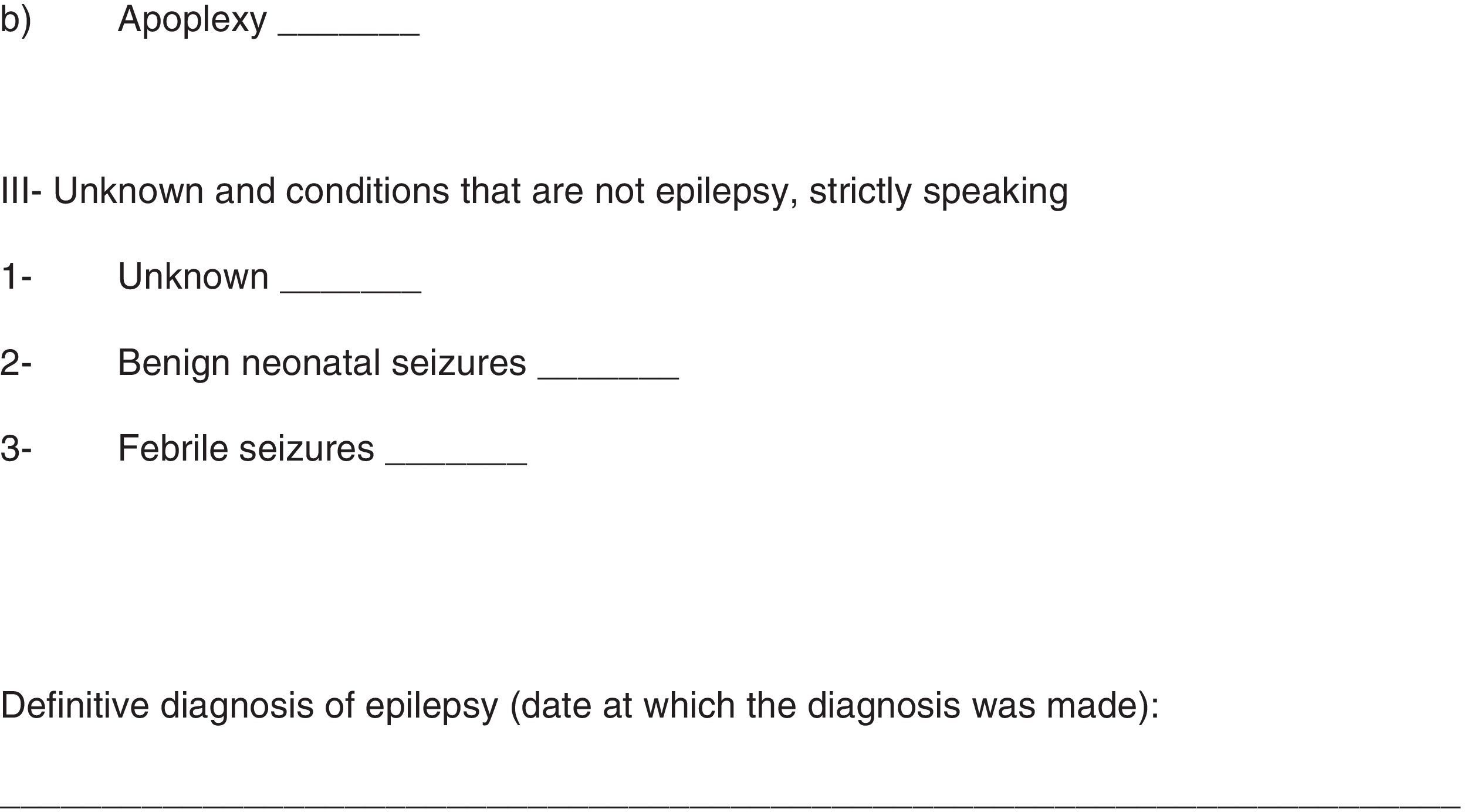

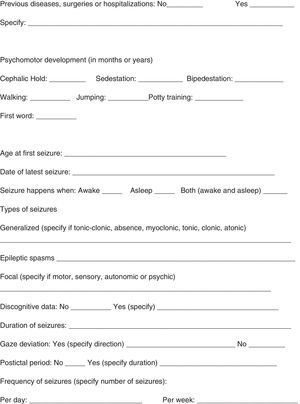

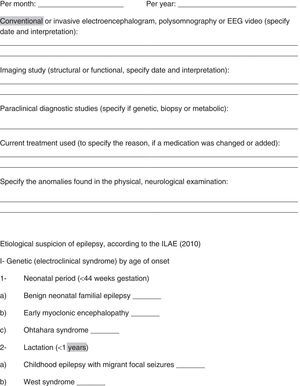

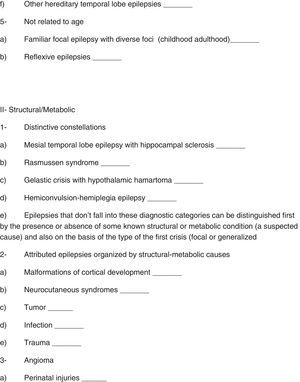

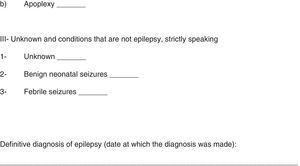

The first group studied was the prospective group, a systematic quick guide was used in this group (see annex 1). Inclusion criteria: patients under 16 years of age who attended the “Dr. José E. González” University Hospital in Monterrey, Nuevo León, México (at its hospital admission area or outpatient clinic) for the first time with suspicion of epilepsy, and who have been assessed by the Pediatric Neurology Service between June 18, 2014 and June 17, 2015. Exclusion criteria: Those patients who were 16 years old or older. Elimination criteria: Patients with an incomplete systematic quick guide, patients with an incomplete clinical file, patients who were ruled out of having epilepsy, and epileptic patients who did not complete the minimum studies (EEG and/or imaging studies) in order to classify them etiologically.

After finishing the prospective group, the retrospective group began. We searched for the registries of every patient who attended the Pediatric Neurology Outpatient Clinic for the first time. All the files from those patients were reviewed, obtaining epidemiological data and etiological diagnoses of all patients with epilepsy. Inclusion criteria: Patients under 16 years of age, with suspicion of epilepsy. Exclusion criteria: Patients who were 16 years of age or older. Elimination criteria: Patients who were ruled out of having epilepsy and patients with incomplete clinical files.

Databases for both groups were set up using Microsoft Excel 2010. Subsequently, a statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20, where a descriptive statistical analysis of the prospective and retrospective groups was completed, then the comparison between both groups was conducted using Pearson's chi square test (for the variables: gender and etiological diagnosis of epilepsy) and the Student T-test (for the age variable). A p<0.05 value was determined as a statistically significant result. This work was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine at the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon on April 20th, 2015, with the registry code NR15-003.

ResultsThe proposed systematic quick guide was conducted on 137 patients with suspicion of epilepsy. Eight patients were ruled out of having epilepsy, and thus were eliminated, and another 9 patients with epilepsy were eliminated as well because they did not comply with the minimum tests (EEG and/or imaging studies) in order to classify them etiologically. The prospective group included 120 patients, while the retrospective group included 71 patients.

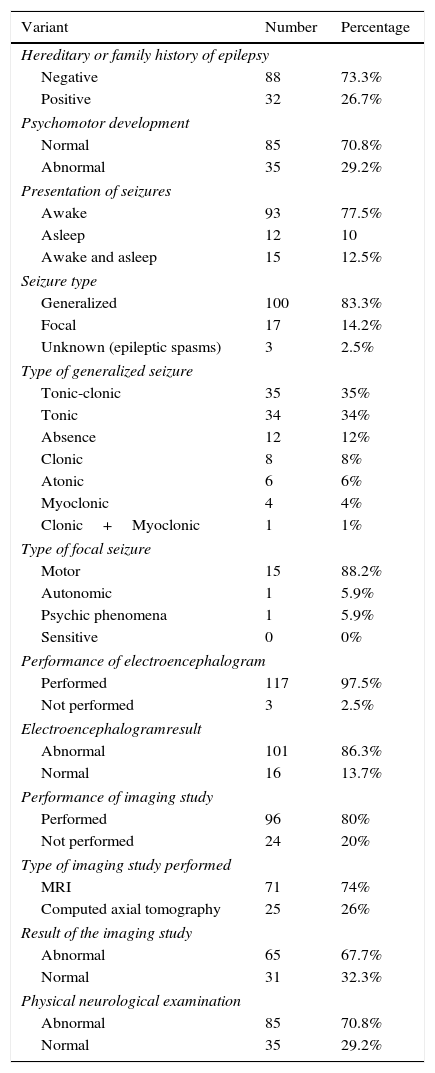

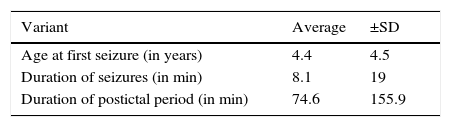

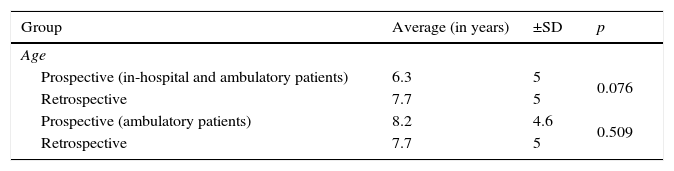

First, a description of the prospective group was done (Tables 1 and 2), and the Denver II tool was used to evaluate the patients’ psychomotor capability. Subsequently, an age comparison between prospective groups (patients admitted plus outpatients, and only outpatients) and the retrospective group was conducted (Table 3). Lastly, a comparison of epilepsy diagnosis by etiological groups was done between prospective groups (patients admitted plus outpatients, and only outpatients) and the retrospective group (Table 4).

Description of the prospective group (in-hospital and ambulatory patients).

| Variant | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Hereditary or family history of epilepsy | ||

| Negative | 88 | 73.3% |

| Positive | 32 | 26.7% |

| Psychomotor development | ||

| Normal | 85 | 70.8% |

| Abnormal | 35 | 29.2% |

| Presentation of seizures | ||

| Awake | 93 | 77.5% |

| Asleep | 12 | 10 |

| Awake and asleep | 15 | 12.5% |

| Seizure type | ||

| Generalized | 100 | 83.3% |

| Focal | 17 | 14.2% |

| Unknown (epileptic spasms) | 3 | 2.5% |

| Type of generalized seizure | ||

| Tonic-clonic | 35 | 35% |

| Tonic | 34 | 34% |

| Absence | 12 | 12% |

| Clonic | 8 | 8% |

| Atonic | 6 | 6% |

| Myoclonic | 4 | 4% |

| Clonic+Myoclonic | 1 | 1% |

| Type of focal seizure | ||

| Motor | 15 | 88.2% |

| Autonomic | 1 | 5.9% |

| Psychic phenomena | 1 | 5.9% |

| Sensitive | 0 | 0% |

| Performance of electroencephalogram | ||

| Performed | 117 | 97.5% |

| Not performed | 3 | 2.5% |

| Electroencephalogramresult | ||

| Abnormal | 101 | 86.3% |

| Normal | 16 | 13.7% |

| Performance of imaging study | ||

| Performed | 96 | 80% |

| Not performed | 24 | 20% |

| Type of imaging study performed | ||

| MRI | 71 | 74% |

| Computed axial tomography | 25 | 26% |

| Result of the imaging study | ||

| Abnormal | 65 | 67.7% |

| Normal | 31 | 32.3% |

| Physical neurological examination | ||

| Abnormal | 85 | 70.8% |

| Normal | 35 | 29.2% |

Age comparison between the prospective groups (in-hospital and ambulatory patients, and only ambulatory patients) and the retrospective group.

| Group | Average (in years) | ±SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Prospective (in-hospital and ambulatory patients) | 6.3 | 5 | 0.076 |

| Retrospective | 7.7 | 5 | |

| Prospective (ambulatory patients) | 8.2 | 4.6 | 0.509 |

| Retrospective | 7.7 | 5 | |

SD: Standard deviation.

Comparison of the epilepsy diagnosis by etiological groups between the prospective groups (in-hospital and ambulatory patients, and only ambulatory patients) and the retrospective group.

| Group | Diagnosis of epilepsy by etiological group | Number | Percentage | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective (in-hospital and ambulatory patients) | Epilepsy of an unknown cause | 3 | 2.5% | <0.001 |

| Epilepsy of a genetic cause | 38 | 31.7% | ||

| Epilepsy of a structural/metabolic cause | 74 | 61.7% | ||

| Conditions that are not epilepsy, strictly speaking | 5 | 4.1% | ||

| Retrospective | Epilepsy of an unknown cause | 37 | 52.1% | |

| Epilepsy of a genetic cause | 8 | 11.3% | ||

| Epilepsy of a structural/metabolic cause | 26 | 36.6% | ||

| Conditions that are not epilepsy, strictly speaking | 0 | 0% | ||

| Prospective (ambulatory patients) | Epilepsy of an unknown cause | 2 | 3.3% | <0.001 |

| Epilepsy of a genetic cause | 33 | 55% | ||

| Epilepsy of a structural/metabolic cause | 22 | 36.7% | ||

| Conditions that are not epilepsy, strictly speaking | 3 | 5% | ||

| Retrospective | Epilepsy of an unknown cause | 37 | 52.1% | |

| Epilepsy of a genetic cause | 8 | 11.3% | ||

| Epilepsy of a structural/metabolic cause | 26 | 36.6% | ||

| Conditions that are not epilepsy, strictly speaking | 0 | 0% |

A total of 120 patients were included in the prospective group and 71 patients in the retrospective group. Average age was 6.3 years for the first group and 7.7 for the second group, compared to a study conducted in Spain where the average age was 5.2 years.6 Gender distribution in the prospective group was 66.7% male and 33.3% female, whereas for the retrospective group the distribution was 66.2% male and 33.8% female, compared to a study conducted in Turkey where 59.3% of the patients were male and 40.7% were female.7 In the prospective group, 26.7% had family history of epilepsy, compared to the 22.2% and 22.5% of studies conducted in Germany8 and Turkey,7 respectively. In the prospective group, 83% of patients presented a generalized seizure crisis, 14.2% presented a focal and 2.5% presented an unknown (epileptic spasms), in comparison to a study conducted in Iceland9 where 58% of patients presented a generalized seizure crisis, 40% presented a focal and 2% presented an unknown; furthermore, a study conducted in the US10 showed 40% of patients with a generalized seizure crisis, 57% with a focal and 3% with an unknown seizure crisis. This gap in percentages can be attributed to the difficulty to express clinical characteristics of the crisis by people who witness them (they might have started focally and later become generalized). Regarding the prospective group, 70.8% of patients presented some anomaly in the neurological physical examination, while a study in Turkey reported only a 25.8% of patients presenting neurological anomalies.7 This could be due to the fact that any neurological abnormality, including abnormalities in the higher brain functions, were considered anomalies in this study. If we change the nomenclature of the epileptic etiology from the symptomatic epilepsy, idiopathic epilepsy and cryptogenic epilepsy of the old ILAE 1989 classification, to the structural/metabolic epilepsy, genetic epilepsy and epilepsy with an unknown cause, respectively, from the new classification from the ILAE 2010, the prospective group (inpatient and ambulatory) had 2.5% unknown cause, 31.7% genetic cause (electroclinical syndromes), 61.7% structural/metabolic causes, and 4.2% which were not epilepsy, strictly speaking. In the retrospective group, we found that 52.1% of the patients had epilepsy of an unknown origin, 11.3% had epilepsy of a genetic origin, 36.6% had epilepsy of a structural/metabolic origin, and 0% had conditions which were not epilepsy, strictly speaking. We can compare our results to those of a study in Iceland,9 where 53% of the patients had epilepsy of an unknown origin, 14% had epilepsy of a genetic origin, 32% had epilepsy of a structural/metabolic origin, and 1% had conditions which were not epilepsy, strictly speaking. Another study in Switzerland11 concluded that 35% of the patients had epilepsy of an unknown origin, 10.3% had epilepsy of a genetic origin, 54% had epilepsy of a structural/metabolic origin, and 1% had conditions which were not epilepsy, strictly speaking.

The positive aspects of this study include the following: it is a cohort, ambi-perspective study in a third level hospital, which is a reference center for the northeast of Mexico. It includes an important number of patients with epilepsy in both groups (prospective and retrospective), and the genders and ages within both groups were homogenous and therefore comparable. Other points in favor of this study are: the inclusion of clinical, demographic, epidemiological and therapeutic characteristics, creating a database for these patients. With the systematic rapid guide proposed in this study for pediatric patients under suspicion of epilepsy, this study showed, with statistical importance, that this guide decreases the “unknown cause” diagnoses of epilepsy and it increases the diagnoses of genetic and structural/metabolic epilepsy for our pediatric patients.

Both study groups were evaluated over the course of a year, and it would be important to extend the follow-up time for these patients. This study has aspects which could be improved: 2.5% of the patients in the prospective group did not recieved an electroencephalogram, due to death or surgical or medical complications, or they were discharged before an electroencephalogram could be performed. 20% of the patients did not recieved any brain imaging studies, some of them due to a lack of economic resources and some due to contraindications from the sedative drugs during the study, due to which some patients may have been subdiagnosed with epilepsy of a structural origin. The genetic studies were no performed on patients from both groups; it will be important for some patients to corroborate their epileptic diagnosis in the future, for which they will have to be cheaper, as they currently cost around 20,000 MXN, which is quite inaccessible for the population at our hospital. This study did not document the frequency of convulsive crises before and after the epilepsy diagnosis, and if there was some electric or clinical improvement after having made the etiological diagnosis using the proposed systematic quick guide, and treating them accordingly. Because of this, we recommend a follow-up study to corroborate clinical or electric improvement in these patients. Some patients in the genetic epilepsy category may also have been “over-diagnosed” when we used the guide to determine their etiology.

Another negative aspect of this study is that we were unable to document all the variables in the retrospective group that we were able to do with the prospective group.

In this study, we can conclude that the rapid systemic guide we used can be corroborated with statistical significance with the increase in the etiological definition of epilepsy in pediatric patients, both in-hospital and ambulatory. This guide can be used by first contact doctors or pediatric neurologists to create a proper diagnostic approach oriented toward all patients under suspicion of epilepsy, to find an etiology diagnosis in accordance with the 2010 ILAE classification. This determination of the specific etiology, as well as the electro-clinical syndromes, will allow us to provide a complete management, oriented on and recommended by the international guides for each patient, which will help us to predict the clinical prognosis of our patients with greater exactitude.

FundingNo financial support was provided.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.