Migraines are common illnesses. Studies conducted in 12 Latin American cities, including two in Mexico, have found that its prevalence in our country is 15%. The rate in gender is 3:1 (Women/Men) worldwide.

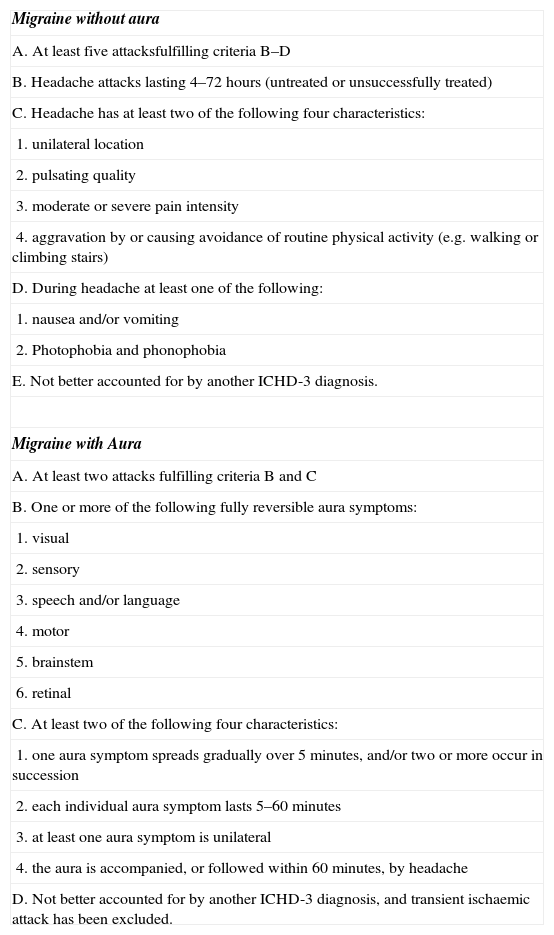

The diagnostic criteria for migraines were published for the first time in 1988, in the first edition of the International Headache Classification, promoted by the International Headache Society, with its second edition in 2003, and a third beta version that will probably be published in 2015. Diagnostic criteria for the different forms of migraines were first described in this document, which has simplified communication among doctors and made possible comparisons between studies. The current migraine criteria (with and without aura) are shown in Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria of frequent migraines.

| Migraine without aura |

| A. At least five attacksfulfilling criteria B–D |

| B. Headache attacks lasting 4–72 hours (untreated or unsuccessfully treated) |

| C. Headache has at least two of the following four characteristics: |

| 1. unilateral location |

| 2. pulsating quality |

| 3. moderate or severe pain intensity |

| 4. aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity (e.g. walking or climbing stairs) |

| D. During headache at least one of the following: |

| 1. nausea and/or vomiting |

| 2. Photophobia and phonophobia |

| E. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis. |

| Migraine with Aura |

| A. At least two attacks fulfilling criteria B and C |

| B. One or more of the following fully reversible aura symptoms: |

| 1. visual |

| 2. sensory |

| 3. speech and/or language |

| 4. motor |

| 5. brainstem |

| 6. retinal |

| C. At least two of the following four characteristics: |

| 1. one aura symptom spreads gradually over 5 minutes, and/or two or more occur in succession |

| 2. each individual aura symptom lasts 5–60 minutes |

| 3. at least one aura symptom is unilateral |

| 4. the aura is accompanied, or followed within 60 minutes, by headache |

| D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis, and transient ischaemic attack has been excluded. |

As in all primary headaches, paraclinic and imaging studies are normal and rarely necessary, exception made for the cases where there is clinical doubt or whenever the patient is too anxious and wishes to be “as certain as you can be”. This may be a valid reason; however it may increase the cost of medical attention and can be problematic in institutions with a high volume of patients.

The management of migraines must contemplate two aspects:

- 1.

Acute management (abortive).

- 2.

Preventive management.

In both cases, the following pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures must be contemplated.

Management generalitiesBefore beginning management of a migraine, as in any other pathological entity, we must ask ourselves, several questions:

- 1.

Are medications necessary?

- 2.

If so, are there parameters to choose one as the best?

- 3.

How will results be measured?

- 4.

Which will the success and failure criteria be to decide a change in management? In other words, how long to maintain a medication before considering it did not work.

- 5.

How long will a successful treatment last?

- 6.

What is the a priori probability of recovery/recurrence?

Answering each and every one of these questions before beginning management is fundamental. It gives the management sense and direction, for both the doctor as well as the patient. Additionally, it brings the patient the feeling that he/she is able to do something, or cooperate in the treatment, and thus the patient perceives he/she has some control over his/her illness.

Abortive managementGeneral guidelines:

- 1.

To treat as early as possible. The instruction is: “Take the medication, or do as indicated, as soon as the patient recognizes if a crisis arises.” Patients learn to recognize when this happens, and we know that abortive treatment loses effect in a direct proportion to the delay in treatment.

- 2.

To have a record of the amount of analgesic used. Set limits and have a “plan B” and “plan C” ready in case of acute therapeutic failure.

- 3.

If we are going to try a medication (i.e. a triptan), try it in at least two crises before declaring therapeutic failure.

- 4.

Remember that the abortive treatment is exactly that: abortive. Although there are exceptions; it must not be used with a schedule. The principle is to NEVER give abortive medication on a schedule. Exceptions would be situations where we can anticipate the onset of the crisis, like migraines associated with menstruation (with regular cycles) or episodic cluster headache. In general, the evolution of the crisis in most migraines is predictable; thus the patient is able to know when to take the medication.

Some patients learn some techniques which can help attenuate the pain or make it disappear. The most utilized method is sleep. The physician can try to compress both superficial temporal arteries in front of the tragus (or on the side where there is pain, if it is hemicranial) in order to try to abort the crisis. Its effectiveness is estimated to be between 30% and 40%.

Diet is reserved for those cases where there is a close temporal relationship between the dietary element imputed and the onset of the crisis. There is no point in giving a restrictive diet a priori. The idea of prohibiting the consumption of specific food, like chocolate, cheese, canned foods, sausages, Chinese food, wine (especially red) or any form of alcohol, among others, is highly popular. The experience in our center is that food trigger are rare.

A careful interrogatory is the best tool to indicate a restrictive diet. Therefore, it is mandatory to keep a headache diary where the patient must record the number of attacks, intensity, time, response to medications, and relationship to external events or foods. This diary will give us the parameters to make changes in management.

MedicationsThe best results of abortive treatment are with medications. Individual sensitivity to a medication is unpredictable; however, we have probabilities of effectiveness. The most effective medications are triptans, and within this group, rizatriptan and eletriptan have the most favorable evidence. However, there is no way of predicting the result of a particular medication in a particular patient. Furthermore, failure of one triptan does not predict the failure of another, thus trying out two or three different triptans may be justified. Our protocol is to start with one of these two, to try it for at least 2 crises, and decide whether or not they worked. If they did not work, switch to a different triptan. The instruction to the patient is: take (or place the wafer of rizatriptan or zolmitriptan over/under the tongue) the medication as soon as the patient recognizes the onset of a crisis. Keep in mind that the effectiveness of the medication decreases with the interval before taking it; once the first dosage of medication is taken we ask them to wait for an hour; if at the end of the hour the crisis is not over, take the second dose. If after the second hour (an hour after the second dose), the crisis has not disappeared, begin with a second, different, medication. The concept of “crisis disappearance” is precisely that: to completely stop not only the pain (which should completely disappear), but also the autonomic and cognitive symptoms, etc. If residual symptoms persist, the probability of recurrence is greater. Recurrence is defined as the reappearance of a crisis in a period shorter than 24h from treatment. It is important to remember that all abortive medications, if used frequently, can cause rebound headaches. Thus the need to keep track of any medication that the patient may take, even if they are over-the-counter medications.

Ergotamine is also effective and low-cost, making it a good option for institutions with a high volume of patients. It has an effectiveness of 40–60% in pain reduction/disappearance. The main problem is that it is highly addictive and we must take all precautions when utilizing potentially addictive drugs: keep track of medication, supervise prescriptions, and review results frequently. Indications to the patient are: initiate treatment as soon as a crisis is recognized; start with 1mg of the usual presentations (two tablets of 0.5mg) and give an additional 0.5mg every half hour until one of these three things occur: the crisis aborts, the patient starts vomiting, or 6 tablets (3mg) are taken. The consumption of more than 6 tablets in a 24h period, or 16 (8mg) in a week is the threshold to develop rebound headaches, in addition to increasing the risk of addiction. If the episode ceases at, let us suppose, 2mg (four tablets), and the pain returns within the following 24h, medication will be given to the patient “as if it were the next half an hour” If longer, it will be considered as a new episode.

Over-the-counter medications are commonly utilized, motu proprio, by patients. Many learn that certain medications or a combination of analgesics give them relief or abort the crisis. The problem with self-medication is that it is the single most important factor for chronification and the transformation of an episodic migraine to a chronic one. There will always be the need to investigate the use, dosage, frequency, etc. of such self-medication. The same principle applies with “natural” medications or herbal medicine. The physician should intentionally ask for their use because there may be active pharmacological principles that can complicate the evolution or result of the treatment.

It is important to keep in mind that the ideal objective of treatment is not to use abortive medications, because there are no more episodes.

It is important not to mix ergotamines and triptans in the same session of treatment. It is a paramount contraindication that one must keep in mind.

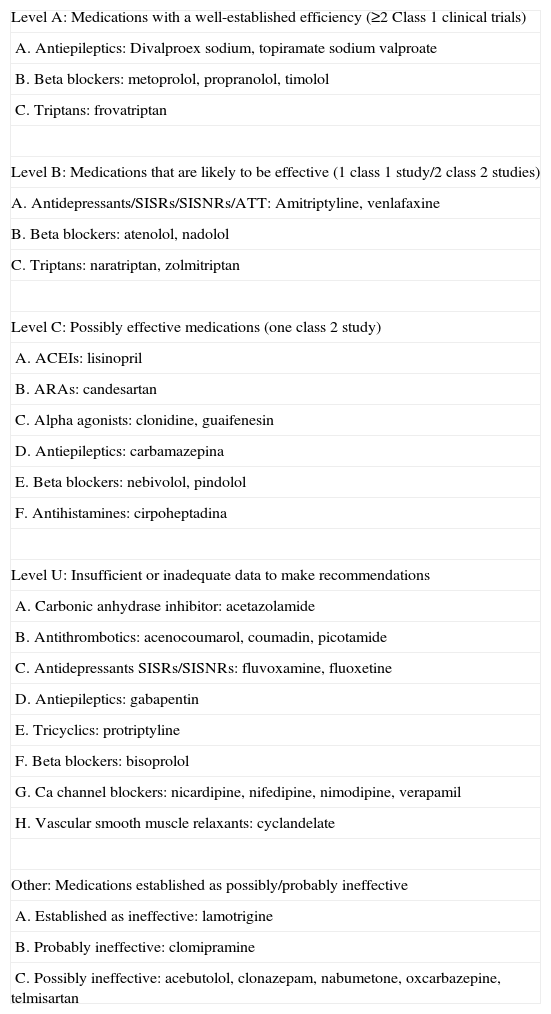

Preventive treatmentThere are publications of international guidelines for preventive management of episodic migraines with medications. Table 2 shows the different groups of drugs with their levels of evidence from the American Academy of Neurology guidelines, 1 that in general agree with the rest of international organizations.

Level of evidence for preventive medicines.

| Level A: Medications with a well-established efficiency (≥2 Class 1 clinical trials) |

| A. Antiepileptics: Divalproex sodium, topiramate sodium valproate |

| B. Beta blockers: metoprolol, propranolol, timolol |

| C. Triptans: frovatriptan |

| Level B: Medications that are likely to be effective (1 class 1 study/2 class 2 studies) |

| A. Antidepressants/SISRs/SISNRs/ATT: Amitriptyline, venlafaxine |

| B. Beta blockers: atenolol, nadolol |

| C. Triptans: naratriptan, zolmitriptan |

| Level C: Possibly effective medications (one class 2 study) |

| A. ACEIs: lisinopril |

| B. ARAs: candesartan |

| C. Alpha agonists: clonidine, guaifenesin |

| D. Antiepileptics: carbamazepina |

| E. Beta blockers: nebivolol, pindolol |

| F. Antihistamines: cirpoheptadina |

| Level U: Insufficient or inadequate data to make recommendations |

| A. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor: acetazolamide |

| B. Antithrombotics: acenocoumarol, coumadin, picotamide |

| C. Antidepressants SISRs/SISNRs: fluvoxamine, fluoxetine |

| D. Antiepileptics: gabapentin |

| E. Tricyclics: protriptyline |

| F. Beta blockers: bisoprolol |

| G. Ca channel blockers: nicardipine, nifedipine, nimodipine, verapamil |

| H. Vascular smooth muscle relaxants: cyclandelate |

| Other: Medications established as possibly/probably ineffective |

| A. Established as ineffective: lamotrigine |

| B. Probably ineffective: clomipramine |

| C. Possibly ineffective: acebutolol, clonazepam, nabumetone, oxcarbazepine, telmisartan |

ACEIs: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARAs: angiotensin receptor antagonists; SISRs: selective inhibitors of serotonin recovery; SISNR: selective inhibitors of serotonin and norepinephrine recovery.

In our country there is no hard data on the effectiveness of medications in our population, however there is some useful information. In 2005, the Headache Study Group of the Mexican Academy of Neurology published a consensus on the management of migraines. Combining experiences, we proposed that our population required lower doses than those published. This data has been commented on international meetings and our colleagues in Latin America and Spain concur with the impression that the doses generally needed in our respective populations are lower. Regarding the preferences of medications, in 2008 our group conducted a national survey on the behavior of neurologists and neuropediatricians in the management of migraines.2

Non pharmacological treatmentAs mentioned above, one must identify the individual triggering factors, should there exist. Even though they are not very frequent, they can be: dietary elements, lack or excess of sleep, irregular meal times, and exposure to intense light. The causal relationship between stress and the production of a crisis is hard to prove, even if it is an idea that “sounds good”. Obesity has been proven as a risk factor for migraine chronification and diminished response to medication. Thus it is recommended, as in other situations, to comply with general rules of hygiene.

Preventive medicationsIn Table 2 there is a list of medications with better evidence. The recommendations for non-neurologists are:

- 1.

Always keep a “headache diary” recording the number of crises, intensity, duration, time, associated symptoms, triggers, effect of used medications, unwanted or adverse effects, need of rescue medication and days without pain. It is fundamental in order to assess the result of the treatment. Aside from this, the MIDAS scale can be used to assess the impact of the disease on activities of daily living.

- 2.

There are no specific guidelines or criteria to start a preventive treatment. In general, we take into account the number of crises and the impact on quality of life. With two or more crises per month the risk/benefit ratio of medications is considered satisfactory to justify the beginning of treatment. In some people (i.e. women with migraines associated with menstruation and regular cycles) we are able to begin “short preventive treatments”, three days before and after the expected onset of the crisis, in each cycle. The same happens in other types of headaches where we are able to predict the onset of a crisis.

- 3.

Learn to manage two or three medications well. Preferably from two different groups.

- 4.

Consider comorbidities. Rule out if the patient is hypertensive, suffers from asthma, anxiety, depression, obesity or other conditions that may indicate or contraindicate a specific medication.

- 5.

Encourage the patient to comply with non-pharmacological measures: enough sleep, regular meal schedules, weight loss, regular exercise, avoiding excesses of food, drinks and alcohol and other general hygiene measures.

- 6.

Establish, along with the patient, a treatment plan with specific measurable goals and commit him to accomplishing them. The incidence of non compliance or abandonment of treatments is high and should always be investigated in each visit, since it may be a cause of therapeutic failure.

- 7.

There is not a guideline or specific evidence on the duration of a successful treatment. The intervals vary. In our national survey, most neurologists and pediatricians considered maintaining a successful treatment for 6–8 months. However, there were responses from 3 to 12 months. In general, a treatment is planned to last 8 months without a crisis. The first two months are useful to assess the effectiveness of the medication.

- 8.

At the beginning of treatment we know there is a probability of effectiveness. We must maintain the use of a medication for at least two months at proper doses before deciding it is not working. A frequent cause of “treatment failure” is not giving it enough time to work. This should be clearly explained to the patient so that he/she cooperates during this period and exert enough patience.

- 9.

At the end of the planned period, stop the medication and observe. The rate of recurrence is 30–40%.

- 10.

While the goal is zero crises, sometimes a few may be tolerated, either because of low tolerability of the medication or because the patient is reluctant to increase the dose. In these cases there are no specific numbers about the cure/recurrence rate after completing a treatment. We must explain to the patient that migraines are diseases that tend to recur in different epochs in life.

- 11.

In case of recurrence after a successful treatment (months or years later), the most reasonable thing to do is to restart the treatment which was useful.

Migraines are a condition which can be controlled and, sometimes “cured”. We ought to understand that the concept of curing is similar to that of other chronic conditions of difficult prognosis (rheumatics, oncological, etc.), which is the absence of recurrence in a determined period of time after treatment. The doctor should pay attention to the details of the treatment in order to communicate to the patient what he is trying to be accomplish, and thus be able to gain his trust and cooperation.

Conflict of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

FundingNo financial support was provided.